Analyse the relationship between the sociodemographic profile of the DIADA study participants and the rate of compliance with the follow-up assessments in the early stage of this project’s intervention for depression and unhealthy alcohol use offered within primary care.

MethodsA non-experimental quantitative analysis was conducted. The sociodemographic data of DIADA [Detección y Atención Integral de Depresión y Abuso de Alcohol en Atención Primaria (Detection and Integrated Care for Depression and Alcohol Use in Primary Care)] study participants had been previously collected. At the time of the evaluation (September 12, 2019), only the participants who had been in the project for a minimum of 3 months were included. By using univariate (Chi-squared) analyses, we studied the association between participants’ sociodemographic profile and their rate of compliance with the first follow-up assessment at 3 months after study initiation.

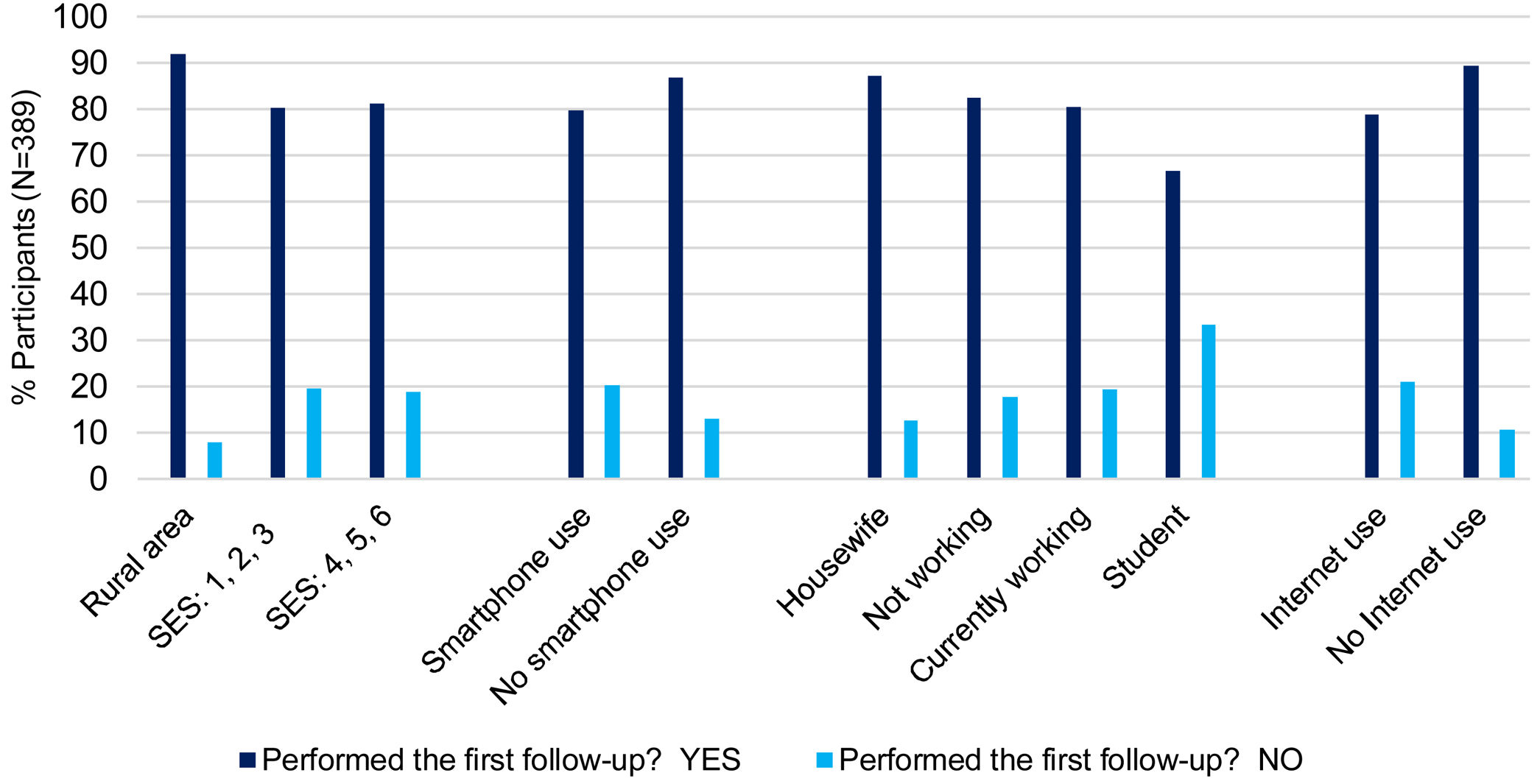

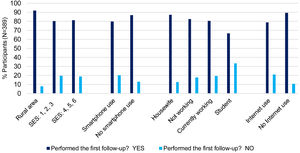

ResultsAt the date of the evaluation, 584 adult participants were identified, of which 389 had been involved in the project for more than 3 months. From the participants included, 320 performed the first follow-up, while 69 did not. The compliance rate to the first follow-up was 82.3% (95 % [CI] 78.1%–86%) and was not affected by: site location, age, sex, civil status, level of education, use of smartphone, PHQ9 score (measuring depression symptomatology) or AUDIT score (measuring harmful alcohol use). Participants who do not use a smartphone, from rural areas and with a lower socioeconomic status, tended to show higher compliance rates. Statistically significant associations were found; participants with lower job stability and a lack of access to the Internet showed higher compliance rates to the early initial follow-up assessment.

ConclusionsThe compliance rate was high and generally constant in spite of the variability of the sociodemographic profiles of the participants, although several sub-groups of participants showed particularly high rates of compliance. These findings may suggest that integrating mental health into primary care allows the structural and financial barriers that hinder access to health in Colombia to be broken down by raising awareness about mental illnesses, their high prevalence and the importance of timely and accessible medical management.

Evaluar la relación entre las características sociodemográficas de los participantes del proyecto DIADA y su tasa de cumplimiento al seguimiento en la fase inicial de la intervención en atención primaria para depresión y consumo riesgoso del alcohol.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo un análisis cuantitativo no experimental. Se utilizaron los datos sociodemográficos de los participantes del proyecto DIADA, previamente recolectados, que hasta el 12 de septiembre del 2019 habían completado al menos tres meses dentro del proyecto. Se evaluó la asociación entre las variables sociodemográficas y el cumplimiento al primer seguimiento de forma uni-variante (χ2).

ResultadosSe identificaron 584 participantes, de los cuales 389 llevaban más de 3 meses involucrados en el proyecto. De éstos, 320 realizaron el primer seguimiento, mientras que 69 participantes no. La tasa de cumplimiento al seguimiento en la fase inicial de la intervención fue superior al 82% (95 % [IC] 78.1%–86%) y no se vio afectada por las variables: centro de atención, edad, sexo, estado civil, nivel más alto de educación, puntaje PHQ9 (evaluando sintomatología de depresión) ni puntaje AUDIT (evaluando consumo riesgoso de alcohol). Pacientes de áreas rurales, con nivel socioeconómico más bajo y que no usan smartphone, mostraron una tendencia a tener mayor cumplimiento al primer seguimiento. Se encontraron asociaciones estadísticamente significativas; los participantes con menor estabilidad laboral y sin acceso a Internet evidenciaron mayor tasa de cumplimiento al seguimiento en la fase inicial de la intervención.

ConclusionesA pesar de la variabilidad del perfil sociodemográfico de los participantes incluidos, la tasa de cumplimiento al seguimiento en la fase inicial del modelo fue alto y constante. Aunque varios subgrupos de participantes mostraron tasas de cumplimiento particularmente altas. A partir de estos hallazgos se podría concluir que integrar la salud mental a la atención primaria permite romper barreras estructurales y financieras que dificultan el acceso a la salud en Colombia; ya que permite crear conciencia sobre las enfermedades mentales, su alta prevalencia y la importancia de que el manejo médico oportuno esté al alcance de todos.

Mental health has a variety of definitions; Colombian Law 1616 of 2013, which seeks to guarantee the full exercise of mental health, defines mental health as: “a dynamic state that is expressed in everyday life through behavior and interaction in such a way that it allows individuals to deploy their emotional, cognitive and mental resources to move through daily life, to work, to establish meaningful relationships and to contribute to the community ".1 Likewise, the 2015 National Mental Health Survey in Colombia defines it as a synonym of emotional well-being and quality of human interactions that favor dignified living conditions and humanization.2

While interpreting the above definitions, mental health is understood as an indispensable psychological and psychosocial resource for the proper functioning and integral development of a human being, which is needed to face vicissitudes and situations that generate emotional tension. However, there are currently limitations that make mental health an ideal, which is not fully embraced as a priority by society.2,3 Indeed, preserving mental health is a challenge for both individual development and, in turn, population development.

In recent years, diagnoses of mental illness have increased globally, with depression being the most prevalent.4,5 Depression affects more than 300 million people and is recognized as the leading cause of disability worldwide.6 According to the 2015 National Mental Health Survey, 1 out of every 20 Colombian adults suffers from depression. Not treating it can bring financial, academic and work problems for both the patient and their family.2

Likewise, harmful use of alcohol results in 3 million deaths every year worldwide and is a casual factor in more than 200 disease and injury conditions.7 In Colombia, 12% of the population between 18 and 44 years of age consume alcohol at risk levels, with a higher proportion of men than women (16% and 9.1% respectively).2 This results in health consequences for the individual, relationship difficulties and a decrease in productivity, which also affects the national economy.2

Despite their high prevalence, mental disorders continue to be a challenge for public health, since most of the people who suffer from them face barriers in access to mental health services. In Colombia, there is a wide gap between coverage and actual access to services. In the case of mental health, the main barriers that prevent access are: attitudinal (stigma and negative beliefs about the health system), structural and financial (distant geographic location and costs in transportation), among others.2

These barriers can markedly impact treatment adherence and retention.8 Moreover, it is known that some determinants of health could also interfere with adherence; the age, level of education, employment situation and sociocultural environment of the patient play an important role.8

Due to this confluence of factors, it may be useful to embed screening and treatment for mental health within a general, primary care setting and highlight its importance in the field of public health. In so doing, it may be useful to train primary care physicians to diagnose, guide treatment and educate the population on mental health disorders to increase knowledge about mental health disorders, their symptoms, their possible treatment and when one may benefit from mental health care.

The DIADA Project (Detection and Integrated Care for Depression and Alcohol Use in Primary Care) is an implementation project that proposes a new model of care which integrates mental health into primary care settings in Colombia. Through training of clinicians and the use of mobile technology in behavioral health, the project facilitates the diagnosis and treatment of depression and risky alcohol consumption in the primary care setting.

ObjectiveAnalyze the relationship between the sociodemographic profile of the DIADA project participants and the rate of compliance with the follow-up assessments in the early stage of the intervention. The follow-up assessments allow the evaluation of the participants’ clinical progress since their enrollment through time, as well as the use of Laddr® (Square2 Systems). Both allow us to analyze the impact of the implementation of the model of care on the health of participants.

MethodsThe protocol for this study was approved by the institutional review boards of Dartmouth College in the U.S. and Pontificia Javeriana University in Colombia.

Data collectionOn September 12, 2019, our research team extracted sociodemographic data of the DIADA study participants who had been enrolled in the project for at least three months from the study’s REDCap database. These data included: site location, date of the interview, date of birth, sex (at birth), civil status, highest level of education, socioeconomic status, employment situation, use of smartphone, use of Internet, score from the screening scales for depression and alcohol consumption (Patient Health Questionnaire and Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, respectively) and the age of the participants. At the time of this data collection, the participants were coded by study number, and no names or identification documents were used.

Statistical analysisThe continuous variables, including age, PHQ-9 and AUDIT score are described by means, standard deviations, and the minimum and maximum values. Subsequently, these variables are categorized for analysis. The variables, including site location, sex (at birth), civil status, highest level of education, socioeconomic status, employment situation, use of smartphone and use of the Internet are treated as categorical and are described by absolute and relative frequencies.

The compliance rate to follow-up assessments in the initial phase of the intervention is reported together with its 95% confidence interval. The association of each of the variables with compliance to the follow-up assessment was studied using Chi-squared tests. Those differences whose p-value was less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Categorizing variablesAge was grouped according to the stages of human development in 4 subgroups, from 18 to 29 years old, from 30 to 49, from 50 to 69 and over 70.9

Regarding civil status, the data were grouped into 4 categories: single (including divorced), in a relationship (married or in free union), widowed and those who preferred not to answer. The level of education was grouped into 7 components according to the degree achieved: none, only primary school, middle school, high school graduate, technician degree, college degree, and postgraduate degree.

PHQ-9 data were grouped according to the questionnaire score: 0–4 negative result, 5–9 mild symptoms of depression, 10–14 moderate symptoms, 15–19 moderate to severe and 20–27 severe.10

The socioeconomic status of the participants was determined according to participants’ self – report of information from their utility bill (for example: water, electricity). The data were grouped as dictated by the Department on National Planning into rural area, socioeconomic strata 1, 2 and 3 (low strata) and socioeconomic strata 4, 5 and 6 (middle – high strata).11 This socioeconomic stratification system in Colombia was created in 1994, classifying urban households into six different categories. Strata 1 households correspond to those of lesser quality and strata 6 to the best conditions.12

The employment status of participants was grouped according to their available time into the following categories: housewife, not working (not looking for work, looking for work, disabled and retired), working (part-time, full-time, independent) and student. This distribution and grouping of the data were chosen by estimating the time spent at home and the time the participants might have available.

DIADA follow-up protocolThe DIADA project participants, who had been diagnosed with depression and/or harmful alcohol consumption when they joined the DIADA study, and had agreed to join the project and signed informed consent, began their follow-up assessments as follows:

- 1

Initial assessment

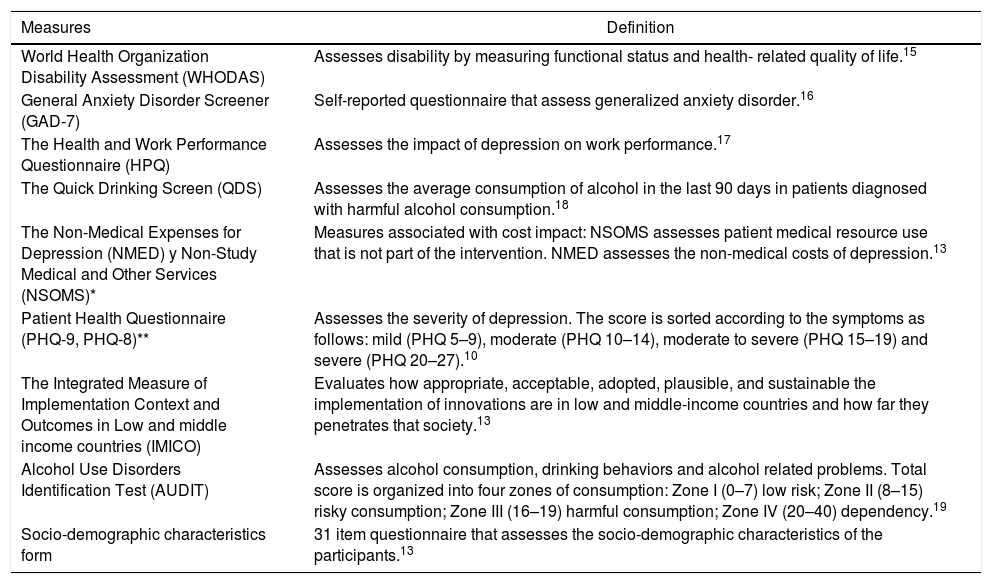

Upon entering the study, participants completed the sociodemographic form as well as the WHODAS, GAD - 7, HPQ, QDS and NMED/NSOMS measures.13 (see Table 1)

Table 1.Measures employed in the follow-up of the DIADA study.

Measures Definition World Health Organization Disability Assessment (WHODAS) Assesses disability by measuring functional status and health- related quality of life.15 General Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) Self-reported questionnaire that assess generalized anxiety disorder.16 The Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) Assesses the impact of depression on work performance.17 The Quick Drinking Screen (QDS) Assesses the average consumption of alcohol in the last 90 days in patients diagnosed with harmful alcohol consumption.18 The Non-Medical Expenses for Depression (NMED) y Non-Study Medical and Other Services (NSOMS)* Measures associated with cost impact: NSOMS assesses patient medical resource use that is not part of the intervention. NMED assesses the non-medical costs of depression.13 Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9, PHQ-8)** Assesses the severity of depression. The score is sorted according to the symptoms as follows: mild (PHQ 5–9), moderate (PHQ 10–14), moderate to severe (PHQ 15–19) and severe (PHQ 20–27).10 The Integrated Measure of Implementation Context and Outcomes in Low and middle income countries (IMICO) Evaluates how appropriate, acceptable, adopted, plausible, and sustainable the implementation of innovations are in low and middle-income countries and how far they penetrates that society.13 Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Assesses alcohol consumption, drinking behaviors and alcohol related problems. Total score is organized into four zones of consumption: Zone I (0–7) low risk; Zone II (8–15) risky consumption; Zone III (16–19) harmful consumption; Zone IV (20–40) dependency.19 Socio-demographic characteristics form 31 item questionnaire that assesses the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.13 - 2

Clinical follow-up

Five clinical assessments were scheduled with each participant every fifteen days (on study days 15, 30, 45, 60 and 75) from the initial assessment, with data collection allowable within a window of seven days around the targeted assessment date. These assessments are conducted by the DIADA team staff over the phone, who inquire about participants’ medical visits in recent days and about their use of the Laddr® digital therapeutic application (Square2 Systems) which provides tools aimed at changing health behavior through an integrated platform that allows self-regulation monitoring for a wide range of populations.13,14 Finally, the PHQ-9 is conducted with participants with depression and the QDS is conducted with participants with harmful alcohol consumption; and if both are present, both tools are applied.

- 3

DIADA study assessment follow- up

Within each year of the DIADA project, there are four official study follow-up assessments, which are performed every three months with a two-week window around the targeted assessment date. In the first and third follow-ups (3 and 9 months), the WHODAS, GAD-7, QDS, NMED / NSOMS and PHQ-8 tools are used. In the second and fourth follow-ups (6 and 12 months) the aforementioned tools are used and the IMICO and HPQ are also added. Additionally, between the first three and six months of participation in the project, a semi-structured qualitative interview is carried out with a sample of participants (n = 30).13

At the date of the evaluation, 584 participants were identified, of which 389 had been involved in the project for more than 3 months, enough time to carry out the initial assessment, the clinical follow-ups and the first DIADA follow-up. From the participants included, 320 performed the first follow-up, while 69 did not. The compliance rate to the first follow-up was 82.3% (95 % [CI] 78.1%–86%).

Data from the sociodemographic profile of the 389 patients were collected. Of those, 208 belong to primary care site #1 located in the urban area of the country's capital city, 111 to primary care site #2 located in a rural area of Boyacá department, and finally 70 participants were from primary care site #3 located in an intermediate city of Boyacá, where patients from rural and urban areas of the country are treated.

The mean age of participants was 52 years, with a minimum age of 18 and a maximum of 87 (SD 17.25). It was found that a little less than half of the participants (45.7%) are between 50 and 69 years old. Of the total, 305 are women, representing 78% of the participants. Regarding civil status, 46.2% of the participants are single (including divorced), 43.4% in a relationship (married or in free union), 9.8% widowed and 0.6% prefer not to answer.

The majority of the participants reached only primary education, representing 29.8% of the total participants, followed by the high school degree with 20.5%. 16.2% have college degree, 14.9% technician degree and 12.8% middle school education. Only 3.9% of the participants report not having any level of education and 1.8% have a postgraduate degree.

Likewise, the scores from the screening tools for depression and alcohol consumption were analyzed. The mean AUDIT score was 2.05 (low risk consumption) with a minimum value of 0 and a maximum of 22 (SD of 4.45). For the PHQ-9 the mean score was 10.8 points (moderate symptoms of depression) with a minimum value of 0 and a maximum of 27 (SD 5.30). These screening tools were applied to all participants regardless of initial diagnosis.

Finally, with depression as the main diagnosis within the study participants, the data from the PHQ-9 score were pooled across all participants. It was found that 0.8% of the participants had a negative result, 48.6% had mild symptoms of depression, 28% moderate symptoms, 13.6% moderate to severe and 9% severe symptoms.

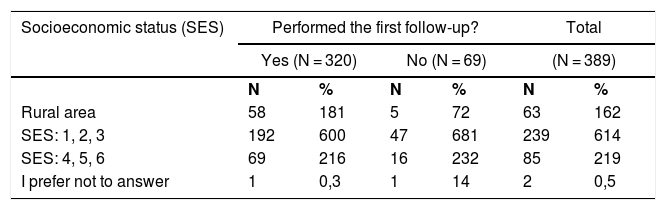

Socioeconomic statusIn Colombia, there are 6 different socioeconomic strata (SES) in the urban area and a single stratum in the rural area. The rural area strata represented 16.2% of the total, strata 1, 2 and 3 represented 61.4%, strata 4, 5 and 6 represented 21.9%, and 0.5% preferred not to answer (see Table 2). A total of 92.1% of the participating population from rural areas completed the three month DIADA study follow-up assessments, while 80.3% of participants from strata 1, 2 and 3 and 81.2% of participants from strata 4, 5 and 6 completed these follow-up assessments.

Participants that performed the first follow-up according to socio-demographic characteristics.

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | Performed the first follow-up? | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 320) | No (N = 69) | (N = 389) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Rural area | 58 | 181 | 5 | 72 | 63 | 162 |

| SES: 1, 2, 3 | 192 | 600 | 47 | 681 | 239 | 614 |

| SES: 4, 5, 6 | 69 | 216 | 16 | 232 | 85 | 219 |

| I prefer not to answer | 1 | 0,3 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 0,5 |

| Do you have a Smartphone? | Yes (N = 320) | No (N = 69) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 201 | 628 | 51 | 739 | 252 | 648 |

| No | 119 | 372 | 18 | 261 | 137 | 352 |

| Employment situation | Yes (N = 320) | No (N = 69) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housewife | 103 | 322 | 15 | 217 | 118 | 303 |

| Not working | 89 | 278 | 19 | 275 | 108 | 278 |

| Currently working | 116 | 363 | 28 | 406 | 144 | 370 |

| Student | 12 | 3,8 | 6 | 87 | 18 | 4,6 |

| I prefer not to answer | 0 | 0,0 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 0,3 |

| Do you use Internet? | Yes (N = 320) | No (N = 69) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 210 | 656 | 56 | 812 | 266 | 684 |

| No | 110 | 344 | 13 | 188 | 123 | 316 |

| Total | 320 | 69 | 389 | |||

Within the sociodemographic information form, participants were asked whether or not they had a smartphone. 64.7% of the participants reported having a smartphone. This was crossed with data of participation in the first follow-up assessment. A non-significant trend was found between the variables: 79.8% of the participants with a smartphone and 86.9% without a smartphone carried out the first DIADA follow-up (see Table 2, Fig. 1).

Employment statusA total of 37% of participants were currently working, followed by 30.3% who were housewives, 27.8% of participants who were not working and finally 4.6% who were students (see Table 2).

Employment data were crossed with the follow-up participation data, in order to identify compliance by employment status. A statistically significant association was found (p = 0.041). The highest percentage of compliance to the first follow-up of the intervention was among the participants who consider themselves housewives (87.3%) and those who are not working (82.4%). Participants who are currently working or studying showed less compliance.

Internet useFinally, 68.4% of participants reported Internet use. These data were crossed with follow-up compliance data. A statistically significant association was found (p = 0.012). Participants who did not use the Internet showed a higher compliance rate to the first follow-up of the intervention (89.4%) compared to those using the Internet (78.9%).

DiscussionThe results of this study show a high rate of compliance with the first follow-up assessment of the intervention for depression and harmful alcohol use under study in the DIADA project, regardless of age, sex, territorial division, level of education, civil status, socioeconomic status, use of smartphone or score on the PHQ-8 and AUDIT tools. The percentage of participation is high, over 82%, and was generally consistent independent of participants’ differing socioeconomic characteristics.

Moreover, it has a heterogeneous population of participants, the majority from urban areas (83.3%) and a smaller proportion from rural areas (16.2%). These findings are representative when compared with the total population that has used the screening tools in the first year of implementation of the DIADA project, where 73.2% came from urban areas and 26.8% from rural areas.20

Likewise, age was variable in this sample. The data were grouped according to the stages of the life cycle, finding that many participants are between 50 and 69 years old (45.7%). This result is similar to that found in the population screened during the first year of the DIADA project, where 63% of the participants were ≥45 years old.20 However, it differs from what was found in the 2015 National Mental Health Survey, where the majority of people with a mental disorder were between 18 and 45 years old, with a lower prevalence in those over 45 years of age.2 This can be attributed to the method of recruitment of the DIADA study (primary health care centers) which makes the populations not comparable.

Results also show a higher participation of women, with a representation of 78% of the sample, which is similar to that of the population screened in the study, where the majority were women seeking health care.20 The latter are factors associated with an increased risk of depression, a diagnosis that varies according to sex in a 2: 1 ratio and is the main diagnosis in the current study.5,6,21

It was found that participants from rural areas have a higher compliance rate to the follow-up (92.1%) compared to those from urban areas (80.5%), although this difference did not reach statistical significance. This could be the result of the implementation of a model that focuses on the primary care setting, managing to overcome some of the structural and financial barriers (remote geographic location and costs of transportation) that hinder access, opportunity and quality in health care.2,22

Despite the fact that the proportion of participants from rural areas is lower, the compliance rate found is high and confirms that having a program that addresses mental health in a primary care setting is feasible and, in turn, improves access to health services, follow-up and likely adherence to treatment.22

Similarly, a trend was found between smartphone use and compliance to the initial phase of the project. Participants who do not use a smartphone had a higher rate of participation in the first follow-up assessment (86.9%). Likewise, a statistically significant association was found between Internet use and participation in the first follow-up. Participants who did not use the Internet showed a higher compliance rate to the follow-up (89.4%). It can be inferred that Internet access is not a limitation for the proposed intervention, since the DIADA project, in addition to the mobile application, also has physical facilities at the primary care sites where the participants find trained staff and access to the Laddr® application, resources that may facilitate their participation in the intervention.13,14,23

Finally, notwithstanding depression being one of the factors mainly associated with absenteeism and lost productivity, it was found that most of the study participants are currently working (37%), which may indicate that the proposed model allows early diagnosis and management of their pathology.24 In addition, a statistically significant association was found: participants who do housework or do not have work showed a higher compliance rate to the first follow-up (87.3% and 82.4% respectively), probably due to available time they can invest in the intervention and assessments included in the model. Nonetheless, complementary strategies could be necessary to increase the participation of those who are working and studying (with less available time), to continue and help facilitate a high compliance rate to the intervention and assessments in those groups as well.

OutreachThe data allow for the characterization of the study sample and the identification of facilitators and limitations in the execution of the early stages of the DIADA project. These findings may aid in the creation of strategies to enhance engagement in the DIADA project and support its reception in the Colombian population.

LimitationsThis study only analyzes participation in the early stages of the DIADA project. A follow-up should be done in future stages to identify any changes in the characterization of the population and determine if the results reported herein are persist or differ over time.

ConclusionThe present study made it possible to characterize the population included in the first stage of the DIADA project, estimate their participation in the first follow-up assessment, and assess the rate of compliance to the initial phase of the study.

A high compliance rate to the first follow-up of the intervention was found, regardless of the sociodemographic variables that could affect compliance. Likewise, the limitations of the project appear to have been mitigated by having both a mobile application as well as physical centers with trained personnel, technology, and Internet access that support the broad inclusion of the participants in the intervention model.

Finally, it could be concluded that integrating mental health into primary care allows breaking down structural and financial barriers that hinder access to health in Colombia by raising awareness about mental illness, its high prevalence and the importance of timely medical management available to everyone. It is hoped that the implementation of the DIADA project may also be able to help break down attitudinal barriers to mental health.

FundingThe investigation reported in this publication was financed by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) via Grant# 1U19MH109988 (Multiple Principal Investigators: Lisa A. Marsch, PhD and Carlos Gómez-Restrepo, MD PhD). The content of this article is only the opinion of the authors and does not reflect the viewpoints of the NIH or the Government of the United States of America.

Conflicts of interestAuthors report not having any conflicts of interest. Dr. Lisa A. Marsch, one of the principal investigators on this project, is affiliated with the business that developed the mobile intervention platform that is being used in this research. This relationship is extensively managed by Dr. Marsch and her academic institution.

Please cite this article as: Cárdenas Charry MP, Jassir Acosta MP, Uribe Restrepo JM, Cepeda M, Martinez Camblor P, Cubillo L, et al. Relación entre las características sociodemográficas de los participantes del proyecto DIADA y la tasa de cumplimiento al seguimiento en la fase inicial de la intervención. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:102–109.