In Colombia, the family APGAR questionnaire is often used to evaluate family function. However, there is no confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to corroborate the proposed one-dimensional structure in Colombian adolescent students.

ObjectiveTo perform CFA on the APGAR family questionnaire in high-school students of Santa Marta, Colombia.

MethodA total of 1462 students of tenth and eleventh grade of official and private schools completed the family APGAR questionnaire. Students between 13 and 17 years old (M = 16.0, SD = 0.8) were included, of which 60.3% were female, and 55.3% were tenth grade students. The χ2, RMSEA, CFI, TLI and SMSR were estimated in the CFA. The internal consistency of the dimension was calculated with Cronbach alpha and McDonald omega coefficients.

ResultsIn the CFA the indexes were χ2 = 9.11, df = 5, P = 0.105; RMSEA = 0.024 (CI90%, 0.000–0.048), CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.996, and SMSR = 0.009. Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.819 and McDonald omega, 0.820.

ConclusionsThe one-dimensional structure of the APGAR family scale is confirmed in high-school students of Santa Marta, Colombia. This questionnaire is reliable and valid for the measurement of family function in school-aged adolescents.

En el contexto colombiano, la escala APGAR familiar es de uso frecuente para evaluar la función familiar. Sin embargo, no se cuenta con un análisis factorial confirmatorio (AFC) que corrobore en estudiantes adolescentes colombianos la estructura unidimensional propuesta.

ObjetivoRealizar un AFC a la escala APGAR familiar en estudiantes de media vocacional de Santa Marta, Colombia.

MétodoUn total de 1462 estudiantes de décimo y undécimo grado de colegios oficiales y privados diligenció la escala APGAR familiar. Se incluyó a los estudiantes de 13 a 17 años (media, 16.0 ± 0.8); el 60.3% eran mujeres y el 55.3%, estudiantes de décimo grado. En el AFC se estimaron los estadísticos χ2, RMSEA, CFI, TLI y SMSR. Se calculó la consistencia interna de la dimensión con los coeficientes alfa de Cronbach y omega de McDonald.

ResultadosEn el AFC los estadísticos fueron: χ2 = 9.11; gl = 5; p = 0.105; RMSEA = 0.024 (IC90%, 0.000–0.048); CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.996 y SMRS = 0.009. El coeficiente alfa de Cronbach fue 0.819 y el omega de McDonald, 0,820.

ConclusionesSe confirma la estructura unidimensional de la escala APGAR familiar en estudiantes de media vocacional de Santa Marta, Colombia. Este cuestionario es confiable y válido para la medición de función familiar en adolescentes escolarizados.

Since the introduction of the Family APGAR questionnaire in 1978, the dynamics or relationships within families have changed significantly with socio-political transformations, particularly those that affect the lives of women, birth control and their increasing incorporation into the workforce in countries around the world.1 A functional family group plays an important role in the general well-being and mental health of adolescents, as it mitigates the possible negative effects of normative and non-normative stressors.2 However, families with adolescent children frequently have conflictive relationships between members due to the difficulties that appear as adolescents consolidate their personal identity and emotional autonomy.3 Consequently, it is necessary to assess family functioning in the comprehensive assessment of adolescents in the context of mental health, and for this it is necessary to have a valid and reliable measurement tool.2,4

Smilkstein designed the Family APGAR questionnaire to rapidly assess family functioning in the context of family medical care.5 Little is known of the psychometric performance of the Family APGAR questionnaire in adolescents, in particular of findings from confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In Chile, Maddaleno et al. applied a version of the APGAR questionnaire with three response options in a sample of 469 adolescents, with an average age of 17 years, and found that the instrument showed acceptable nomological validity, correlating the scores with various mental health indicators. However, they omitted to report on its reliability in terms of internal consistency, and dimensionality.6 In Colombia, in a group of 91 students aged 11–17, Forero et al. observed in an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) that the questionnaire showed a single factor that explained 55.6% of the total variance.7 Likewise, in 656 adult patients from Granada, Spain, Bellón et al. found that the EFA showed a single factor for 61.9% of the variance.8 In 1321 patients aged 15–96 years from a health centre in Mexico City, Gómez et al. observed a questionnaire factor for 52.9% of the variance.9 More recently, in a Colombian study of 227 adults aged 22–94 years from a dental service in Cartagena, Díaz-Cárdenas et al. reported that the APGAR questionnaire showed two goodness-of-fit indicators that contradicted the expected one-dimensional structure.10

In adolescents, the systematic evaluation of family functioning is essential in primary care and family health, given the relationship between family dysfunction and important outcomes, such as academic performance, depressive symptoms or substance use.11 However, it is necessary to be certain about the validity of the measurement with instruments such as the Family APGAR questionnaire, given the significant variations in the performance of these scales according to the social and cultural characteristics of the participants.12–14

The objective of this research was to confirm the one-dimensional structure of the Family APGAR questionnaire in year 10 and 11 secondary school students in Santa Marta, Colombia.

MethodsThe present study was reviewed and approved by a research ethics committee. The parents or guardians signed the informed consent and the students gave their voluntary consent to complete the research booklet, in accordance with the Colombian standards for research involving humans.15

A sample of 1462 year 10 and 11 students participated. Students aged 13–17 (16.0 ± 0.8) were included in the research, 60.3% women, 55.3% were year 10 students, 49.6% were from low income families, and 76.1% with family dysfunction (scores <16).

The participants filled in the Family APGAR questionnaire in the classroom. The version used was the one adapted for Colombia by Arias et al.16 and previously analysed psychometrically in a study with adolescents from Bucaramanga.7 This questionnaire is made up of five items that explore adaptability, partnership, growth, affection and resolve. Each item offers five response options (never, almost never, sometimes, almost always and always) that are scored from 0 to 4; consequently, total scores are between 0 and 20.5

In the CFA, five indicators of goodness of fit were determined: χ2, RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation), CFI (comparative fit index), TLI (Tucker-Lewis index), and SMSR (standardised mean square residual). The five indicators were expected to show acceptable values to accept the one-dimensional questionnaire structure: χ2 with p < 0.05, RMSEA around 0.06, CFI and TLI > 0.90 and SMSR <0.05.17 In addition, the internal consistency of the factor identified was calculated with Cronbach's alpha18 and McDonald's omega19 coefficients. Values between 0.70 and 0.95 were expected for these coefficients.12–14,20 The calculations were performed with STATA 13.0.21

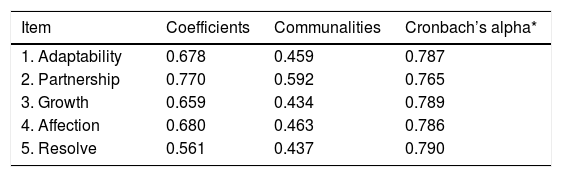

ResultsThe Family APGAR questionnaire scores found were between 0 and 20 (mean, 12.4 ± 4.2; median, 13 [interquartile range, 10–15]). In the CFA, the coefficients observed were between 0.561 and 0.770, and the communalities were between 0.437 and 0.592. All the coefficients and communalities are presented in Table 1. The goodness-of-fit statistics for the questionnaire were χ2 = 9.11; gl = 5; p = 0.105; RMSEA = 0.024 (90% confidence interval [90% CI], 0.000−0.048); CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.996 and SRMR = 0.009.

Coefficients, communalities and Cronbach’s alpha.

| Item | Coefficients | Communalities | Cronbach’s alpha* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Adaptability | 0.678 | 0.459 | 0.787 |

| 2. Partnership | 0.770 | 0.592 | 0.765 |

| 3. Growth | 0.659 | 0.434 | 0.789 |

| 4. Affection | 0.680 | 0.463 | 0.786 |

| 5. Resolve | 0.561 | 0.437 | 0.790 |

Regarding the internal consistency of the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.819 and McDonald's omega coefficient was 0.820. Table 1 shows Cronbach's alpha with the omission of the item.

DiscussionThe CFA of the APGAR questionnaire in the present study shows that it is a scale with a single dimension, with excellent internal consistency, in year 10 and 11 students from Santa Marta, Colombia.

In this study, the CFA demonstrated the one-dimensional structure of the APGAR questionnaire in adolescent students aged 13–17 years. However, the finding cannot be compared with previous studies due to the lack of research in populations in the same age groups and the application of CFA as a statistical approximation to the structure of the questionnaire. Only Díaz-Cárdenas et al. performed CFA on the response pattern of 227 adults in a dental service, and failed to demonstrate the one-dimensional structure, observing a χ2 value with <5% probability (p = 0.001) and RMSEA > 0.06 (0.155; 90% CI, 0.107−0.209).10 In CFA and other tests of psychometric performance, these divergences in the findings are common, according to the demographic characteristics of the population, for complex constructs such as family functionality, and greater if they are explored with a small number of items.22

The internal consistency of the Family APGAR questionnaire in the present study was observed to be >0.80, measured with two coefficients - Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega. This data is consistent with previous studies that reported Cronbach's alpha coefficient values between 0.77 and 0.90.7–11 However, they highlight the need to use more robust tests, such as CFA, to guarantee the dimensionality of an evaluation instrument.22,23 The practical difficulty of making the empirical data fit a previously theorised factor structure is evident.22,24,25

It is important to have an instrument with excellent validity indicators to quantify family functioning in adolescents. Family functionality is a variable to consider in studies in adolescent-age populations, since family functioning is associated in this population with general outcomes such as academic performance and others related to emotional well-being and mental health, such as legal and illegal substance use, the presence of depressive symptoms and self-harming behaviours.11,26–29

This study shows the one-dimensional structure of the Family APGAR questionnaire in adolescent students after 40 years of use in the clinical context, which corroborates the validity of the instrument and its usefulness in measuring family functioning in some contexts. Unidimensionality is a highly appreciated characteristic because it implies that the measurement is valid and focused on a single feature or a high percentage of its variance, without the distortion that can be generated by the presence of minor accessory features that make the measurement inaccurate.30,31 However, the CFA findings have internal validity only and can never be generalised to other samples or populations. Periodic verification is necessary of the performance of mental health measurement instruments.24,32

It is concluded that the Family APGAR questionnaire is an instrument with a clear one-dimensional structure, with high internal consistency, in year 10 and 11 adolescent students from Santa Marta, Colombia. These findings should be corroborated in future research.

FundingThis study was financed by the Vicerrectoría de Investigación [Directorate of Research] of the Universidad del Magdalena through Resolution 0347 of 2018 (Fonciencias 2017 call for proposals).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Campo-Arias A, Caballero-Domínguez CC. Análisis factorial confirmatorio del cuestionario de APGAR familiar. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:234–237.