The most recent issue of Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría [Colombian Psychiatry Journal], included the article “Factors Related to Psychoactive Substance Use in an Educational Institution in Jamundí Valle, Colombia”. Although it is true that studies of this type are necessary in Public Health, knowledge of such phenomena demands the conducting of rigorous research which would allow us to make valid and reliable conclusions about the nature of the problem.

With that in mind, after critical reading of the document, I found a series of weaknesses, namely:

- 1.

Type of study: in the abstract, it is mentioned that a cross-sectional study was carried out with an analytical approach that simulates cases and controls. It is important to point out that under the universally known and accepted classification of epidemiological studies, this type of approach does not exist;1,2 thus the validity of these results may be extremely compromised. Therefore it is (epidemiologically) incorrect to mix two types of study to aim for greater rigour in the design. Although the instruments of measurement in these studies can categorise the subjects as probable “cases” and “not cases”, this should not be confused with having designed a “case-control” study that starts with this selection a priori.

- 2.

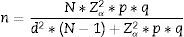

Sample size: with the parameters provided by the authors, and taking into account that it is a descriptive cross-sectional observational study with qualitative dichotomous dependent variable, the calculation was simulated manually using the formula for point estimation of a proportion with finite population, as follows:

When replacing the elements of the equation, the result is 115 subjects, which does not match what was reported by the authors (n=146).

- 3.

Measurement instruments: it is important to point out that, to a large extent, the validity and reliability of the results of a research study depend on the psychometric properties (validity and reliability) and on the operational performance of the measurement instruments used.3 In the case of this study, there is no detailed description of which instrument was used for the measurement (screening) of psychoactive substance (PAS) use; which presupposes the potential presence of measurement bias. In accordance with the above, the investigators could have used screening questionnaires designed for this purpose, such as VESPA (Vigilancia Epidemiológica sobre el uso indebido de Sustancias PsicoActivas [Epidemiological Surveillance on the Misuse of Psychoactive Substances]), which has been used in other research studies in the area.4,5

- 4.

Statistical approach: the conduct of a case-control study must not only be taken into account as a prerequisite (which the authors did not carry out) for the choice of statistical methods for analysis using regression. Having obtained a prevalence of current consumption of PAS of 35%, an estimator that should be interpreted as a frequent event (epidemiologically), the statistical method to determine related factors (with the consumption of PAS) should not be a logistic regression, as in this case the estimators (odds ratio) tend to overestimate the true size of the effect when the outcome is common (>20%). Therefore, the ideal association estimators are the prevalence ratios (PRs), owing to the design used and the outcome of the dependent variable; additionally, PRs are quickly interpretable compared to ORs in cross-sectional studies.6 The PRs need to be calculated through the function of generalised linear models (GLMs),7 which are easily obtained through specialised statistical packages such as Stata.

- 5.

Interpretation of the results: it cannot be deliberately concluded that 51 cases and 95 controls were identified. As already mentioned, what cross-sectional studies achieve when a survey is applied is an adequate screening of possible cases, as long as an appropriate measuring instrument is used and the psychometric properties of that instrument are tested.8 Thus, with only one filter question applied to the participants, it is methodologically incorrect to make inferences about the prevalence of the phenomenon or even the identification of “cases” and “controls”. In line with the above, the best available measurement instrument, known as the gold standard, should be used.8

The above observations show that the findings presented have questionable practical utility for public health and new and better studies are therefore needed which, with correct methodological approaches, allow valid and reliable inferences to be made about the phenomenon being studied.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Simancas Pallares M. Comentario editorial sobre «Factores relacionados con el consumo de sustancias psicoactivas en una institución educativa de Jamundí Valle, Colombia». Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2018;47:2–3.