Colombia is facing a rising epidemic of intravenous heroin use. Knowledge of the methadone-assisted treatment programmes in the country is crucial in order to propose improvement strategies.

Methods13 programmes from priority regions were surveyed. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients attending the programmes, a description of the services offered, their methadone treatment protocols, the various barriers to treatment and the causes of treatment abandonment were reviewed.

Results12/13 questionnaires were analysed with a total of 538 active patients. Most of the patients attending these programmes were men (85.5%) between 18 and 34 years-old (70%). Forty percent (40%) were intravenous drug users and 25% admitted sharing needles. The comorbidities associated with heroin use were mental illness (48%), hepatitis C (8.7%) and HIV (2%). Psychiatric comorbidity was more likely in patients attending the private sector (69.8% vs. 29.7%; p<0.03). The initial average dose of methadone administered was 25.3±8.9mg/day, with a maintenance dose ranging from 41 to 80mg/day. Lack of alignment with primary care was perceived to be the most serious barrier to access, ahead of problems with insurance and prejudice towards treatment with methadone (p<0.05). Health Administration and insurance problems (p<0.003), together with the lack of availability of methadone (p<0.018) and relapse (p<0.014) were the most important reasons for abandonment of treatment.

ConclusionsThe treatment protocols of these programmes offer different levels of development and implementation. Some of the barriers to access and reasons for abandonment of treatment with methadone can be mitigated with better health administration.

Colombia está enfrentado una epidemia emergente del consumo endovenoso de heroína. Un conocimiento de los programas existentes que ofrecen tratamiento asistido con metadona en el país es necesario para que se puedan proponer estrategias de mejoría.

MétodosSe encuestaron 13 programas de regiones prioritarias. Se evaluaron las características demográficas y clínicas de los usuarios, así como los servicios ofrecidos por estos programas, sus protocolos de tratamiento con metadona y las diferencias en las barreras al tratamiento y las causas de abandono del tratamiento.

ResultadosSe analizaron 12/13 cuestionarios, con un total de 538 pacientes activos. La mayoría de los pacientes eran varones (85,5%) de 18 a 34 años (70%). El 40% eran usuarios de drogas intravenosas y el 25% admitió compartir agujas. Entre las comorbilidades asociadas con el consumo de heroína se encontró la enfermedad mental (48%), la hepatitis C (8,7%) y la infección por el VIH (2%). La comorbilidad psiquiátrica se asocia más con los pacientes que acuden al sector privado (el 69,8 frente al 29,7%; p<0,03). La media de la dosis inicial de metadona es 25,3±8,9mg/día y las dosis de mantenimiento van de 41 a 80mg/día. La falta de articulación con atención primaria fue una barrera más sentida que los problemas con la cobertura del seguro médico y los prejuicios del tratamiento con metadona (p<0,05). También, los problemas administrativos y de la aseguradora (p<0,003), la falta de suministro de metadona (p<0,018) y la recaída en el consumo (p<0,014) son las razones más significativas de abandono del tratamiento.

ConclusionesEstos programas tienen diferentes niveles de desarrollo e implementación en los protocolos de tratamiento. Algunas de las barreras de acceso y de las causas de abandono del tratamiento pueden mitigarse mejorando la administración de salud.

Heroin use in the Colombian population had a lifetime prevalence of 0.14% (31,852 people) and a last year prevalence of 0.03% in 2013.1 In contrast, in 2015 the lifetime prevalence of heroin use among the over 45s was 0.7%, although the authors did not report lifetime or last year data on opioid use in other age groups.2 The 2013 estimates indicate that there may have been around 7000 heroin users in Colombia in the last year.1 Although these figures appear small when compared to other countries in the region with higher levels of opiate use, such as Bolivia (0.6%), Brazil (0.5%) or Chile (0.5%),3 this growing demand in Colombia may overwhelm the capacity of the available treatment services.

In a study conducted in Medellín in 50 patients with heroin addiction who accessed treatment, it was found that the majority were male (74%) with an average age of 23, having begun using heroin on average at the age of 18. Some 38% also had psychiatric comorbidities, with a risk of HIV infection that was curiously not associated with intravenous use, but rather with practising unprotected sexual intercourse.4 To assess the situation of patients who do not access treatment services in Colombia, a further study was conducted using the respondent-driven sampling (RDS) method,5 which assessed 42 heroin users in the community, revealing intravenous use in 24%, with 14% admitting to sharing syringes.6 The estimated prevalence of HIV infection in the population of intravenous drug users (IVDUs) is 3.8% in the city of Medellín and 1.9% in the city of Pereira.7,8 Although these prevalences of HIV infection among IVDUs are lower than the consolidated 7.4% reported for Latin America and the Caribbean,9 the risk of an HIV infection spreading rises exponentially in situations involving the sharing of intravenous drug paraphernalia.

In Colombia, the official response to intravenous heroin use and the risks thereof includes legislation (Law 1566 of 2012) guaranteeing comprehensive care to those who use psychoactive substances, and the Política Nacional para la Reducción del Consumo de Sustancias Psicoactivas y su Impacto [Colombian National Policy for the Reduction of the Use of Psychoactive Substances and their Impact],10 which defines the sector-specific approaches to this issue, and which is implemented in the form of the Plan Nacional de Respuesta al Consumo Emergente de Heroína [Colombian National Plan in Response to Emerging Heroin Use],11 building on the Colombian mental health policy.12 These initiatives together ensure that services to treat users of heroin and other opiates are covered under the Plan Obligatorio de Salud (POS) [Colombian Compulsory Health Plan].13 The general approaches of these initiatives are prevention, mitigation, overcoming the addiction and increasing response capacity.10 In this regard, various methadone-assisted treatment (MAT) centres have been established in the seven regions with the highest prevalences of this issue, although they may be at different stages of development and implementation as the details of their current status are unknown. These programmes have been using methadone in tablet form only, as liquid methadone is not available in Colombia. The use of liquid methadone with digital administration systems facilitates the safe dosing and monitoring of the drug during treatment in countries where it is available.

The central objectives of this study were to describe the status of the programmes in these regions that are using MAT, to identify the demographic and clinical characteristics of the users of these services and the programmes’ characteristics, to identify the patterns of use and average methadone dose used in these programmes, and to assess the severity of potential barriers to access and causes of treatment abandonment. An additional objective of this study was to describe the significant differences between public and private programmes. These include non-profit organisations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). It is hoped that this more detailed knowledge of users, programmes and barriers to treatment might help us to identify areas that require improvement and increase our ability to put forward strategies to mitigate the impact on health.

Material and methodsThe programmes were selected from the seven Colombian regions and cities where heroin use is most concerning (Antioquia, Bogotá, Cauca, Norte de Santander, Quindío, Risaralda and Valle del Cauca). All programmes in these locations that had reported MAT for opioid use disorder were selected. The assessment instrument was designed based on the questionnaire used to characterise the services available in the United States,14 which was adjusted based on a literature review15–17 and adapted to the country's needs with feedback from experts with knowledge of treatment centres in Colombia. The instrument comprises five sections assessing: (a) user characteristics; (b) programme characteristics; (c) severity of barriers to access and causes of treatment abandonment; (d) treatment models and medications used; and (e) specific details of the MAT protocols used by each programme. The instrument was consensually reviewed by three national experts, then emailed to the 13 different programmes providing MAT for opioid use disorder (heroin and opiate addiction). The SPSS statistics program (IBM SPSS Statistics 22) was used for the descriptive analysis of all the programmes and the differences between public programmes (n=7) and private programmes (n=5). Student's t-test was used for the differences between the averages of continuous variables, while Pearson's χ2 test was used for the differences between the proportions of categorical variables. Differences in the amplitude of barriers to access and causes of treatment abandonment were analysed using a scale from 0 (never occurs) to 5 (always present), using ANOVA and post hoc analysis to assess the differences between each barrier or reason. Statistical significance was defined using two-tailed alpha tests and p value <0.05.

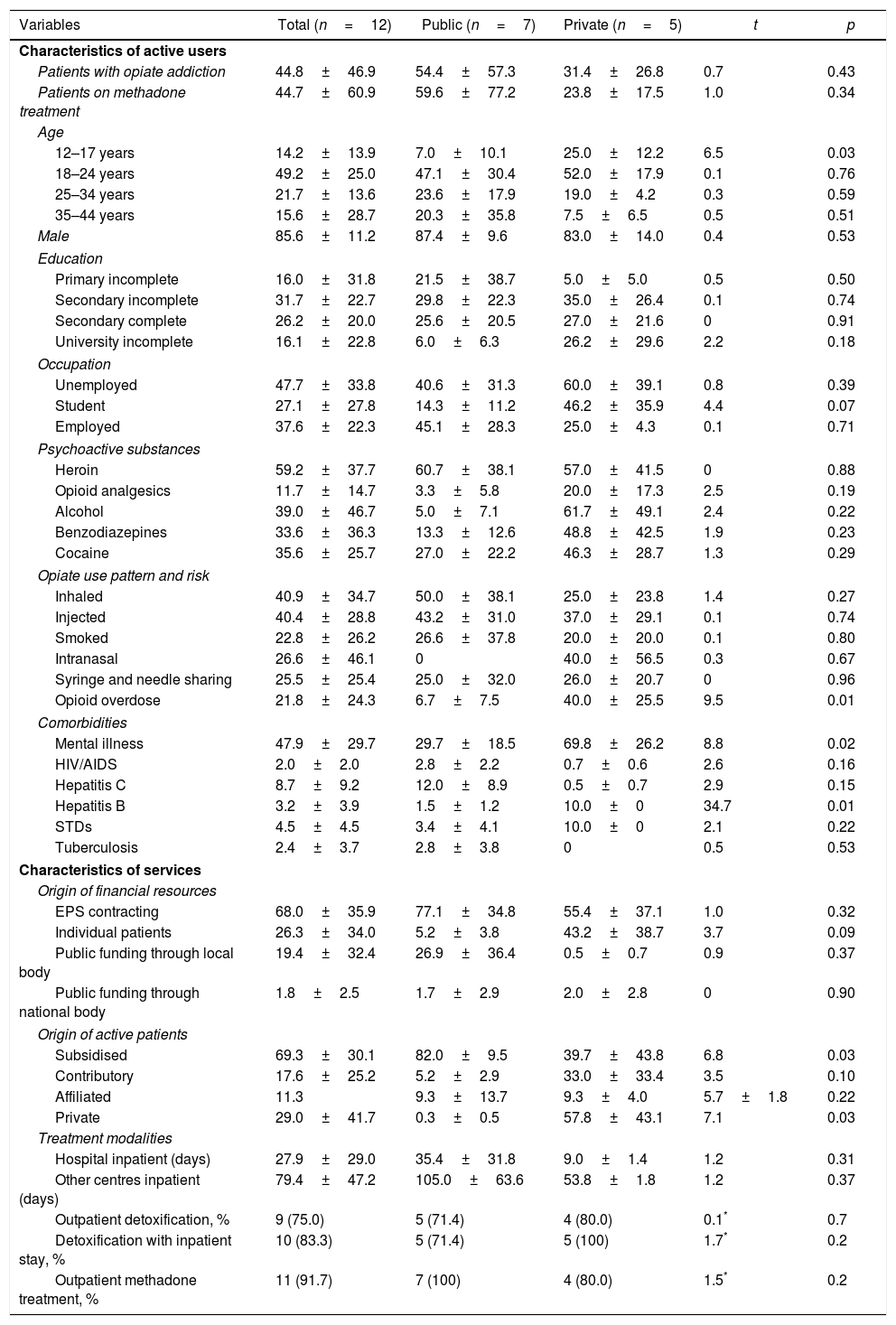

ResultsTwelve questionnaires were received out of the thirteen sent to the selected facilities in the seven regions and cities prioritised. Table 1 shows the aggregated characteristics of the programmes, with descriptions of the patients on active treatment and the services provided by the programmes, as well as the relevant differences between public and private facilities.

Methadone-assisted treatment programmes in Colombia.

| Variables | Total (n=12) | Public (n=7) | Private (n=5) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of active users | |||||

| Patients with opiate addiction | 44.8±46.9 | 54.4±57.3 | 31.4±26.8 | 0.7 | 0.43 |

| Patients on methadone treatment | 44.7±60.9 | 59.6±77.2 | 23.8±17.5 | 1.0 | 0.34 |

| Age | |||||

| 12–17 years | 14.2±13.9 | 7.0±10.1 | 25.0±12.2 | 6.5 | 0.03 |

| 18–24 years | 49.2±25.0 | 47.1±30.4 | 52.0±17.9 | 0.1 | 0.76 |

| 25–34 years | 21.7±13.6 | 23.6±17.9 | 19.0±4.2 | 0.3 | 0.59 |

| 35–44 years | 15.6±28.7 | 20.3±35.8 | 7.5±6.5 | 0.5 | 0.51 |

| Male | 85.6±11.2 | 87.4±9.6 | 83.0±14.0 | 0.4 | 0.53 |

| Education | |||||

| Primary incomplete | 16.0±31.8 | 21.5±38.7 | 5.0±5.0 | 0.5 | 0.50 |

| Secondary incomplete | 31.7±22.7 | 29.8±22.3 | 35.0±26.4 | 0.1 | 0.74 |

| Secondary complete | 26.2±20.0 | 25.6±20.5 | 27.0±21.6 | 0 | 0.91 |

| University incomplete | 16.1±22.8 | 6.0±6.3 | 26.2±29.6 | 2.2 | 0.18 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Unemployed | 47.7±33.8 | 40.6±31.3 | 60.0±39.1 | 0.8 | 0.39 |

| Student | 27.1±27.8 | 14.3±11.2 | 46.2±35.9 | 4.4 | 0.07 |

| Employed | 37.6±22.3 | 45.1±28.3 | 25.0±4.3 | 0.1 | 0.71 |

| Psychoactive substances | |||||

| Heroin | 59.2±37.7 | 60.7±38.1 | 57.0±41.5 | 0 | 0.88 |

| Opioid analgesics | 11.7±14.7 | 3.3±5.8 | 20.0±17.3 | 2.5 | 0.19 |

| Alcohol | 39.0±46.7 | 5.0±7.1 | 61.7±49.1 | 2.4 | 0.22 |

| Benzodiazepines | 33.6±36.3 | 13.3±12.6 | 48.8±42.5 | 1.9 | 0.23 |

| Cocaine | 35.6±25.7 | 27.0±22.2 | 46.3±28.7 | 1.3 | 0.29 |

| Opiate use pattern and risk | |||||

| Inhaled | 40.9±34.7 | 50.0±38.1 | 25.0±23.8 | 1.4 | 0.27 |

| Injected | 40.4±28.8 | 43.2±31.0 | 37.0±29.1 | 0.1 | 0.74 |

| Smoked | 22.8±26.2 | 26.6±37.8 | 20.0±20.0 | 0.1 | 0.80 |

| Intranasal | 26.6±46.1 | 0 | 40.0±56.5 | 0.3 | 0.67 |

| Syringe and needle sharing | 25.5±25.4 | 25.0±32.0 | 26.0±20.7 | 0 | 0.96 |

| Opioid overdose | 21.8±24.3 | 6.7±7.5 | 40.0±25.5 | 9.5 | 0.01 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Mental illness | 47.9±29.7 | 29.7±18.5 | 69.8±26.2 | 8.8 | 0.02 |

| HIV/AIDS | 2.0±2.0 | 2.8±2.2 | 0.7±0.6 | 2.6 | 0.16 |

| Hepatitis C | 8.7±9.2 | 12.0±8.9 | 0.5±0.7 | 2.9 | 0.15 |

| Hepatitis B | 3.2±3.9 | 1.5±1.2 | 10.0±0 | 34.7 | 0.01 |

| STDs | 4.5±4.5 | 3.4±4.1 | 10.0±0 | 2.1 | 0.22 |

| Tuberculosis | 2.4±3.7 | 2.8±3.8 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.53 |

| Characteristics of services | |||||

| Origin of financial resources | |||||

| EPS contracting | 68.0±35.9 | 77.1±34.8 | 55.4±37.1 | 1.0 | 0.32 |

| Individual patients | 26.3±34.0 | 5.2±3.8 | 43.2±38.7 | 3.7 | 0.09 |

| Public funding through local body | 19.4±32.4 | 26.9±36.4 | 0.5±0.7 | 0.9 | 0.37 |

| Public funding through national body | 1.8±2.5 | 1.7±2.9 | 2.0±2.8 | 0 | 0.90 |

| Origin of active patients | |||||

| Subsidised | 69.3±30.1 | 82.0±9.5 | 39.7±43.8 | 6.8 | 0.03 |

| Contributory | 17.6±25.2 | 5.2±2.9 | 33.0±33.4 | 3.5 | 0.10 |

| Affiliated | 11.3 | 9.3±13.7 | 9.3±4.0 | 5.7±1.8 | 0.22 |

| Private | 29.0±41.7 | 0.3±0.5 | 57.8±43.1 | 7.1 | 0.03 |

| Treatment modalities | |||||

| Hospital inpatient (days) | 27.9±29.0 | 35.4±31.8 | 9.0±1.4 | 1.2 | 0.31 |

| Other centres inpatient (days) | 79.4±47.2 | 105.0±63.6 | 53.8±1.8 | 1.2 | 0.37 |

| Outpatient detoxification, % | 9 (75.0) | 5 (71.4) | 4 (80.0) | 0.1* | 0.7 |

| Detoxification with inpatient stay, % | 10 (83.3) | 5 (71.4) | 5 (100) | 1.7* | 0.2 |

| Outpatient methadone treatment, % | 11 (91.7) | 7 (100) | 4 (80.0) | 1.5* | 0.2 |

Affiliated: with national resources for the uninsured low-income population; Contributory: with direct payment by workers; EPS: health promotion company; Subsidised: with funding from the state and other supportive sources.

The total number of patients on active MAT was 536. Some 85.6% of these patients on treatment were male, predominantly in the 18–34 age group; 26.2% had completed secondary education and 47.7% were unemployed. The group of under 17s was significantly more represented in the private sector than in the public sector (25% vs. 7%; p<0.04) and more likely to be students, although this trend was not significant (46.2% vs. 14.3%; p=0.07). Approximately 40% of these patients used heroin intravenously, while the other 40.9% inhaled it. Some 25.5% of heroin users reported having shared syringes and needles. Some 21.8% of service users indicated that they had suffered a heroin overdose, the majority in the private sector (40% vs. 6.7%; p<0.02). Regarding use of other substances, 39% of patients declared concomitant use of alcohol and 33.6% of benzodiazepines, substances that increase the risk of overdose and death when used alongside methadone treatment. Although the inappropriate use of opioid analgesics appears to be a more prevalent problem among users of private sector services (20% vs. 3.3%), this difference is not significant. Other conditions associated with heroin addiction include mental illness (48%), hepatitis C (8.7%), HIV infection (2%) and tuberculosis (2.4%). Psychiatric comorbidity is significantly more associated with patients with opiate addiction who use private sector services (69.8% vs. 29.7%; p<0.03).

Programme characteristicsThe treatment programmes are mostly of medium complexity. Regarding the origin of resources, 68% receive contracts from Health Promotion Companies [Empresas Promotoras de Salud—EPS]; 26.3% from individual patients and 19.4% from local bodies. As was anticipated, private facilities obtain 43.2% of their resources from individual patients, compared to 5.3% for public facilities. Regarding funding sources, 69.3% of active patients are members of the subsidised healthcare regime, and in turn are more heavily represented in the public sector (82% vs. 39.7%; p<0.04). The treatment methods offered to patients with heroin addiction by the twelve programmes examined include outpatient detoxification (75%), detoxification with an inpatient stay (83.3%) and outpatient MAT (91.7%).

The treatment programmes generally have multidisciplinary treatment teams. All have a psychologist and psychiatrist; 91.7% include occupational therapy, social work and nursing; 66.7% have a general practitioner; 50% include a nutritionist and qualified operator; 33.3% have a toxicologist and rehabilitation educator; and 25% have a physician specialising in drug addiction and a psychologist specialising in neuropsychology. The majority of these teams (>75%) screen for both substance use and its associated problems and mental illness, determine the presence of drugs in urine (83.3%) and perform blood tests for hepatitis B (66.7%), hepatitis C (58.3%) and HIV (75%) as well as testing for tubercle bacilli in sputum (75%). Only two (16.7%) of these teams actively seek out patients in the community, as well as assessing alcohol use using breathalyser tests. Only one of the treatment programmes (8.3%) offers vaccination against hepatitis B, as well as being a reception and treatment centre for patients in the judicial system.

The centres use the methadone treatment guidelines developed by the Centro de Atención y Rehabilitación Integral en Salud Mental [Centre for Comprehensive Care and Rehabilitation in Mental Health] (CARISMA)18 or the WHO19 as a reference. As matters currently stand, the treatment centres have not yet implemented harm reduction strategies such as providing syringes or rooms for clean drug use for people who cannot achieve or are not interested in achieving total abstinence.

Most of the programmes offer psychotherapy interventions with various orientations, but almost never use 12-step therapy. Two programmes are educating patients and their relatives about first-aid manoeuvres for opiate overdose. Some 41.7% of the programmes carry out educational activities on reducing the risks of intravenous drug use.

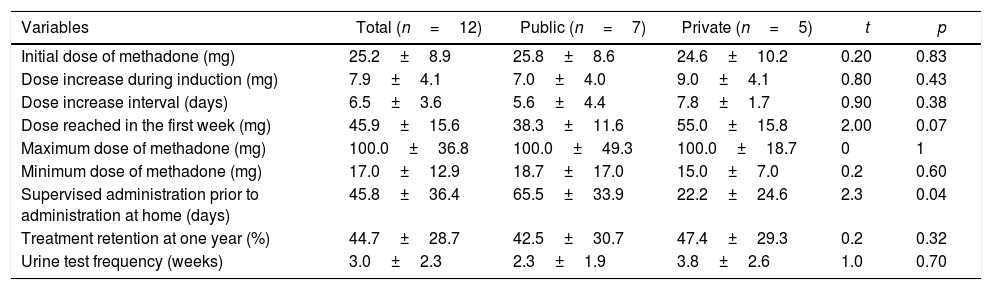

Methadone-assisted treatment protocolsThe total number of patients on active MAT was 536 with a mean of 44.7±60.9 (range 0–199) active patients. As can be seen in Table 2, the average initial dose during outpatient methadone induction was 25.3±8.9 (15–40)mg/day. This initial dose of methadone was increased by an average of 7.9±4.1mg every 6.5±3 days up to an average dose of 45.9mg/day (range 20–80) of methadone in the first week; nine programmes (75%) said they used maintenance doses in the 41–80mg/day range, while two programmes used maintenance doses at <40mg/day and one programme at >80mg/day. The average maximum daily dose reported was 100mg/day (range 40–180). Two of the programmes reported that, per protocol, they always induced methadone treatment with the patient hospitalised, before continuing it on an outpatient basis. The average number of days required before the patient is able to take methadone at home without supervision by medical staff is 45.8±36.4 days (range 1–90). Public sector programmes supervise methadone administration for an average of 65±33.9 days, significantly longer than private programmes (22 days; p=0.04). Finally, the programmes perform an average of one toxicology test every three weeks (range 1–8).

Methadone-assisted treatment protocols. Colombia, 2014.

| Variables | Total (n=12) | Public (n=7) | Private (n=5) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial dose of methadone (mg) | 25.2±8.9 | 25.8±8.6 | 24.6±10.2 | 0.20 | 0.83 |

| Dose increase during induction (mg) | 7.9±4.1 | 7.0±4.0 | 9.0±4.1 | 0.80 | 0.43 |

| Dose increase interval (days) | 6.5±3.6 | 5.6±4.4 | 7.8±1.7 | 0.90 | 0.38 |

| Dose reached in the first week (mg) | 45.9±15.6 | 38.3±11.6 | 55.0±15.8 | 2.00 | 0.07 |

| Maximum dose of methadone (mg) | 100.0±36.8 | 100.0±49.3 | 100.0±18.7 | 0 | 1 |

| Minimum dose of methadone (mg) | 17.0±12.9 | 18.7±17.0 | 15.0±7.0 | 0.2 | 0.60 |

| Supervised administration prior to administration at home (days) | 45.8±36.4 | 65.5±33.9 | 22.2±24.6 | 2.3 | 0.04 |

| Treatment retention at one year (%) | 44.7±28.7 | 42.5±30.7 | 47.4±29.3 | 0.2 | 0.32 |

| Urine test frequency (weeks) | 3.0±2.3 | 2.3±1.9 | 3.8±2.6 | 1.0 | 0.70 |

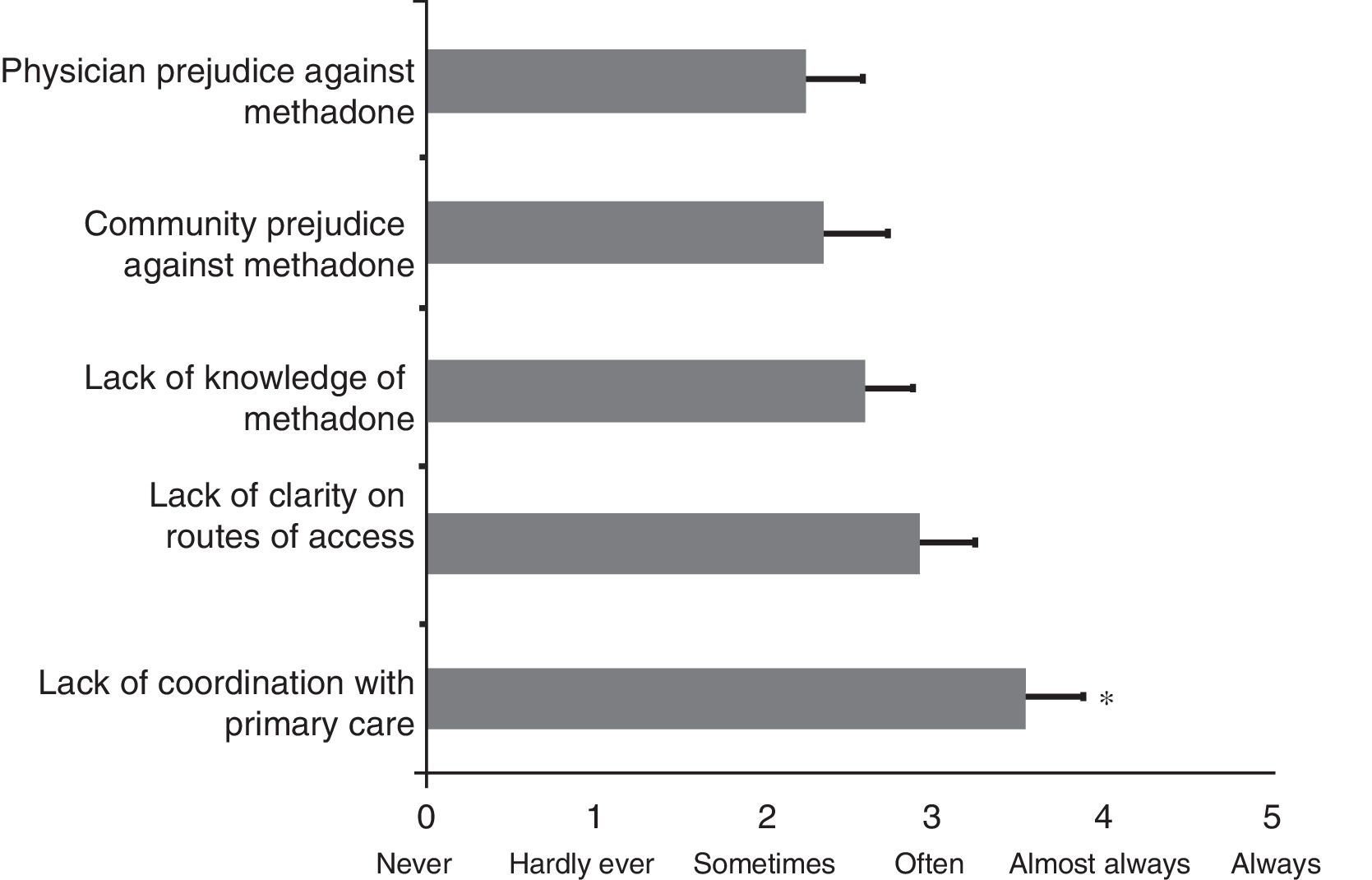

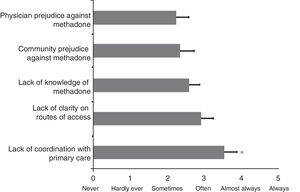

After assessing barriers to accessing treatment, the results indicate that there is a significant difference between them (ANOVA, F=2.4; df=4; p=0.05). Fig. 1 shows the results of the programmes’ assessment with regard to barriers to accessing MAT, using a scale from 0 (never) to 5 (always). The results of the post hoc analysis reveal that lack of coordination with primary care is significantly the greatest obstacle to accessing MAT, with a mean of 3.54±0.3 on this assessment scale compared with lack of knowledge of MAT (2.58±0.2; p<0.05), community prejudice against methadone (2.33±0.3; p<0.014) and physician prejudice against MAT (2.25±0.3; p<0.009). Although the lack of clarity regarding the route of access (2.92±0.3) came second to lack of coordination with primary care, this was not statistically significant. In addition, 66.7% of programmes identified that EPS delays in treatment orders was the most prevalent circumstance acting as a barrier.

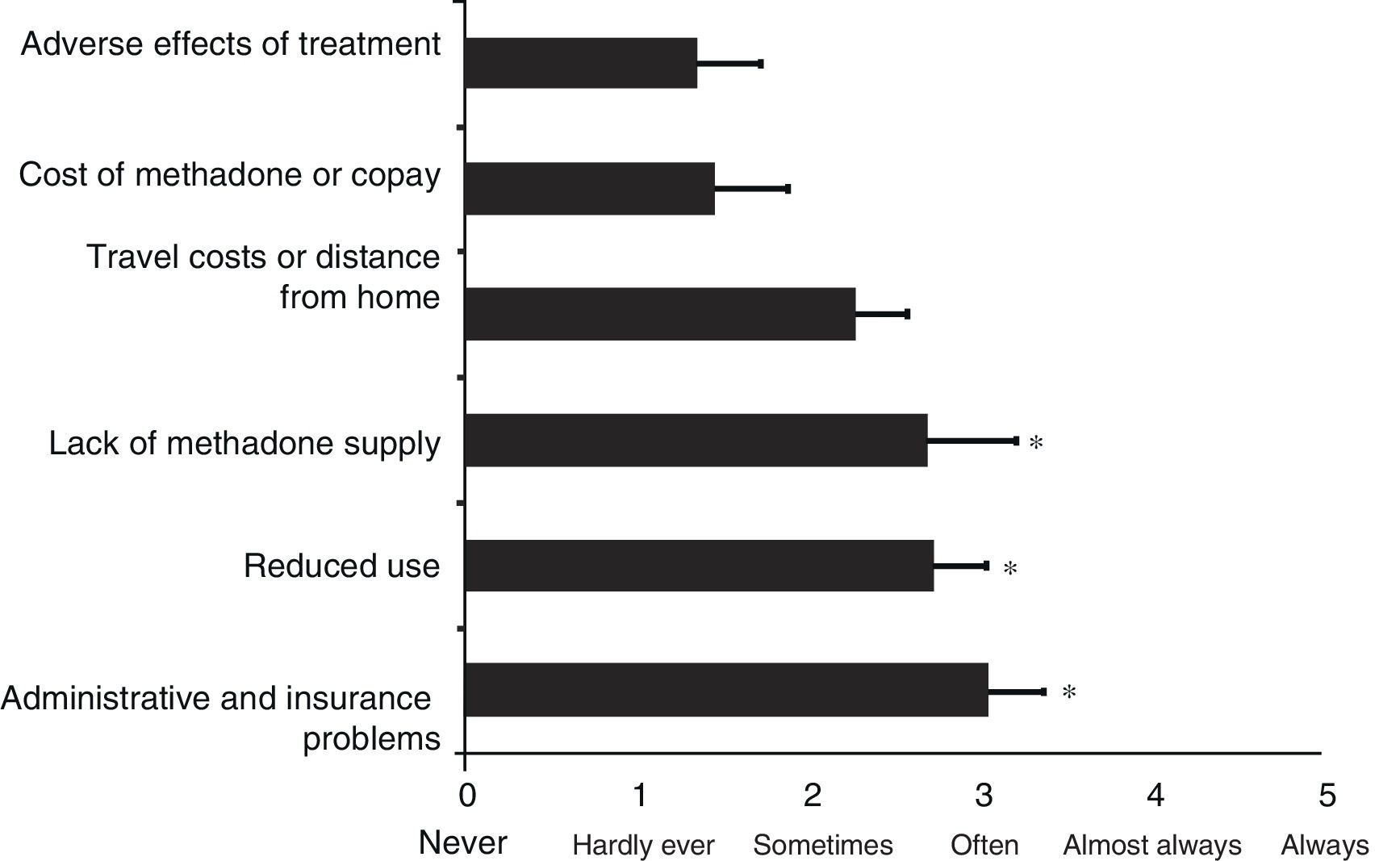

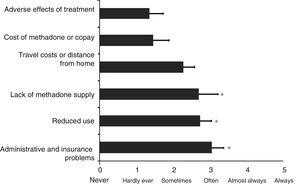

The results of the causes of MAT abandonment indicate significant differences between the programmes analysed (ANOVA, F=3.5; df=5; p<0.009). Fig. 2 shows the results of the programmes’ assessment with regard to causes of MAT abandonment, using the same scale from 0 (never) to 5 (always). The results of the post hoc analysis suggest that lack of methadone supply is a significantly more common cause of treatment abandonment, with a mean of 2.70±0.5 (p<0.018), together with reduced use (2.73±0.3; p<0.014) and administrative and insurance problems (3.05±0.3; p<0.003), compared with adverse effects of treatment (1.36±0.3). In contrast, travel costs or distance from home (2.27±0.3; p=0.09) and the cost of the methadone or copay (1.45±0.4; p=0.8) are not significantly different from the adverse effects of treatment (Fig. 2). The results of differences between public and private programmes for barriers to treatment and treatment abandonment are not presented as they were not significant.

DiscussionThis study's findings suggest that in general the Colombian MAT programmes analysed have unequal development and implementation of national and international protocols. Among the twelve programmes assessed, some are in the early phases of this implementation, while others are much more developed. For example, one programme reported 150 new patients with opioid addiction in the last year, but only had five patients on MAT. It appears this imbalance could be explained by the fact that the only therapeutic target accepted by this centre is overcoming the addiction, or 100% abstinence from all substances, including marijuana. This administrative decision is a consequence of the restrictions of EPSs, which in this case only cover treatments for overcoming the addiction, not mitigation. Some of the organisations administering healthcare resources and services (EPS and IPS [health service providers]) have their own therapeutic objectives and agendas that do not necessarily match those of the Colombian Health and Social Security System's (SGSSS) policies and plans.

The use of injected heroin by 40% of individuals, with 25.5% sharing syringes and needles, is in keeping, although with increased prevalence, with the results of a study conducted in users in the community, which found 25% intravenous use with 14% sharing intravenous drug paraphernalia.7,8 The window of opportunity represented by those patients on active treatment who have HIV (2%) or hepatitis C (8.7%) infections is rightly highlighted; it is to be hoped that all programmes might therefore offer education, detection tests and harm reduction strategies with the aim of avoiding the fate of other countries where HIV and hepatitis C rates among intravenous drug users have reached up to 50%20–23 and 90%.22,24–28 Of equal importance in the care of these patients with opiate addiction is the risk of accidental or intentional overdose, which in this study was significantly more common among private sector patients.

Some of the programmes studied preferred to start induction of methadone treatment with the patient hospitalised, before continuing it on an outpatient basis. The internationally accepted standard is that hospitalisation is not necessary when inducing methadone treatment.29 This hospitalisation can be justified only in the event of serious psychiatric comorbidities with suicidal ideation or complex medical problems, making it the exception rather than the rule.

Centres specialising in MAT must also offer harm reduction programmes including needle exchange programmes30,31 or rooms for clean drug use to encourage people who are not yet interested in stopping using heroin to make use of treatment centres.32 Programmes in which patients receive methadone daily must achieve a balance between the effectiveness of the MAT and the need to incorporate measures to reduce the risk of accidental overdose or overdose due to interaction with depressants such as alcohol and benzodiazepines. If they are to do this, they must be capable of identifying the people exposed to this risk, warning them of the inherent risk of interaction of these substances with methadone, performing alcohol breathalyser tests and developing protocols to temporarily reduce the methadone dose based on alcohol consumption or the use of benzodiazepines.

Equally, as not all programmes have the capacity for patients to receive methadone daily at the treatment centre, which is the ideal and the safest option, other alternative means of supplying medication need to be sought. Currently, methadone tablets are dispensed for long treatment periods, which risks them ending up on the black market, patients failing to return to treatment centres and a consequent drop in psychosocial interventions. One practical solution implemented in some Colombian programmes, which, although not optimal, does offer a degree of safety, is the involvement of an advisor who keeps the methadone and only administers the daily dose indicated by the physician. Another potential alternative to this dilemma is to supply methadone daily from a mobile vehicle that travels around the city and also enables people with transport difficulties to access treatment.

In addition to the fact that 50% of all the programmes’ users are relatively young, the under 17s and students are turning more to the private sector. The reason for this finding is not clear, but one possible explanation for this significant difference may be an increase in the prevalence of opiate use at these ages among the people who access this sector or, conversely, a barrier to people in these age groups and situations accessing treatment in the public sector as another alternative.

With regard to barriers to accessing treatment, lack of coordination with primary care is considered to be the most significantly problematic barrier. Currently, just one treatment programme participating in MAT is effectively coordinating with primary care. Training primary care teams to screen, identify and refer patients with heroin addiction could be one of the actions best able to improve this coordination. Specialist centres will need to provide guidance on referrals, training and consultancy. With time, primary care teams will have the experience to treat stable, low-complexity patients. This is an opportunity for developing and strengthening ties that can be implemented to facilitate access to services and make supervised doses the rule rather than the exception. The second most noted barrier to accessing treatment is the lack of clarity regarding how to access it. Most prevalently, this takes the form of service orders rejected or denied by the EPS, followed by lack of clarity for users regarding coverage of the service. These are some of the most common reasons for patients abandoning treatment. There is therefore a need to train both administrative and clinical staff in the basics of MAT so that the former are not an obstacle and the latter administer it appropriately and correctly according to the highest internationally recognised standards.

Three of the barriers to accessing treatment identified—lack of knowledge of the existence of methadone treatment services among the population, community prejudices and those of the medical profession—can be changed through a sustained information and education campaign. Likewise, increased education on the problems associated with the use of psychoactive substances and their pharmacological treatments in the schools that train healthcare professionals could increase knowledge and reduce prejudice towards medication-assisted treatments for addiction problems.

Finally, together with the administrative and insurance problems described above, the lack of availability of methadone in the country is a significant cause of treatment abandonment that must be prevented. Users in Colombia frequently see their 40mg tablets changed to 10mg tablets and vice versa depending on availability. This means the price of the medication varies constantly and leads to dissatisfaction among users because the 10mg tablets are more expensive. The health authority is obliged to guarantee the permanent availability of any medication used in the treatment of chronic diseases, as is the case, in order to improve adherence to treatment, prevent abandonment and improve recovery rates. Liquid methadone, together with daily dispensing using a digital pump system, can increase safe administration during outpatient induction, reduce diversions to the black market and facilitate medication withdrawal when this is indicated. Moreover, importing other medications such as buprenorphine and naltrexone should be considered as a means to increase access to treatment for opiate addiction. In order to resolve the issue of the national availability of methadone, an increase in Colombia's permitted methadone quota will need to be negotiated by the country's representative on the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs. Given that this is an emerging cross-sectoral public health issue in Colombia, the national authorities—such as the Ministry of Health, the Treasury, the Ministry of Education and the National Narcotics Fund—must guarantee sufficient appropriations to meet the demand for prevention, mitigation and overcoming the addiction that this issue entails. It is essential that the national authorities guarantee methadone acquisition that meets demand, in order to guarantee continuity of treatment. We recommend that liquid methadone be given immediate consideration, along with the respective digital dispensing equipment, as well as the inclusion in the SGSSS’ national formulary of other medications that could reasonably be a means to confront this emerging public health problem.

The Colombian state has made enormous efforts to confront heroin addiction from a harm reduction standpoint. This experience is useful and has its strengths and weaknesses, having contributed to stemming not only the financial costs, but more particularly the personal and community costs of pain and decline.

ConclusionsThe increase in the use of heroin in some regions and cities in Colombia is concerning due to the evidence of intravenous use, with the practice of sharing paraphernalia, and an increase in the prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C infections. Data on treatment services highlight the rapid adaptation of existing programmes in mental health and drug addiction to incorporate the use of MAT, which are at different stages of development from the protocols implemented to date. The lack of infrastructure and experience in starting MAT appears to have driven a need for hospitalisation, which will surely change with improvements to the conditions in which MAT is administered. The barriers to access and retention problems identified can be easily mitigated through better health administration, including the Colombian authorities guaranteeing the continuous availability of methadone for the treatment of opiate addiction. The Colombian experience confronting intravenous heroin use as an emerging disease with a recognised public health impact may serve as a guide for other South American states with higher levels of use.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingUNODC contract no. 0354 of 2014.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Our thanks go to Disney Niño (UNODC) and Aldemar Parra of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection of the Republic of Colombia for their constant feedback and comments on the initial version of the text that served as the basis for this article. We would also like to thank the directors and delegates of the participating facilities who responded to the questionnaires and took part in discussion round tables.

Please cite this article as: González G, Giraldo LF, DiGirolamo G, Rey CF, Correa LE, Cano AM, et al. Enfrentando el problema emergente de consumo de heroína en Colombia: los nuevos programas de tratamiento asistido con metadona. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2019;48:96–104.

This work was presented at the 77th Annual Scientific Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence (CPDD) in Phoenix, Arizona (USA), on 13–19 June 2015.