The DIADA project, understood as a mental healthcare implementation experience in the context of a middle-income country like Colombia, promotes a necessary discussion about its role in the global mental health framework. The following article outlines the main points by which this relationship occurs, understanding how the project contributes to global mental health and, at the same time, how global mental health nurtures the development of this project. It reflects on aspects like the systematic screening of patients with mental illness, the use of technology in health, the adoption of a collaborative model, the investigation on implementation, a collaborative learning and the Colombian healthcare system. These are all key aspects when interpreting the feedback cycle between the individual and the global. The analysis of these components shows how collaborative learning is a central axis in the growth of global mental health: from the incorporation of methodologies, implementation of models, assessment of outcomes and, finally, the dissemination of results to local, regional and international stakeholders.

El proyecto DIADA, entendido como una experiencia de implementación de un modelo de atención en salud mental, en el contexto de un país de medianos ingresos como Colombia, incentiva la necesaria discusión acerca de su papel en el marco de la salud mental global. El siguiente artículo expone los puntos principales en los que ocurre esta relación, entendiendo cómo el proyecto contribuye a la salud mental global, y de forma paralela, cómo la salud mental global nutre el desarrollo de este proyecto. Se reflexiona sobre aspectos como el tamizaje sistemático de pacientes con trastornos mentales, el uso de tecnologías en salud, la adopción del modelo colaborativo, la investigación en implementación, el aprendizaje colaborativo y el sistema de salud colombiano, puntos claves al momento de interpretar este ciclo de retroalimentación entre lo individual y lo global. El análisis de estos componentes demuestra cómo el aprendizaje colaborativo es un eje central en el crecimiento de la salud mental global, desde la incorporación de metodologías, implementación de modelos, evaluación de desenlaces y, finalmente, la difusión de los resultados obtenidos entre actores locales, regionales e internacionales.

Global health is an area of knowledge with the main objective of achieving equity in health services on a global level. This concept has been developed based on multidisciplinary knowledge in the health sciences, social sciences, economics, communications and other fields.1 While there is a direct relationship between "tropical medicine" and "international health", global health seeks to recognise the interdependence of all the world's countries and populations and to jettison colonialist models of unidirectional relationships.

The Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978 sparked global interest in a health model based on primary care as a way to meet the needs of the global population.2 This declaration cited mental health as something merely to be promoted and did not emphasise it in the primary care model adopted.3

At the start of the 1990s, the Caracas Declaration (1990) called for restructuring of psychiatric care in Latin America towards a community model. This represented a major milestone on a regional level.4 Curiously, for a long time, this declaration remained largely unknown amongst global mental health (GMH) players, then gained traction when it resurfaced in the 2018 Lancet Commission.5 Significant advances have been made in mental health on a regional level, and substantial changes have been applied to the mental healthcare models of multiple countries, such as the Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) led in Colombia and worldwide by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the World Health Organization (WHO).6 Nevertheless, it is clear that much work remains to be done by all players.7,8

The Detection and Integrated Care for Depression and Alcohol Use in Primary Care (DIADA) project reflects the historical course of global, regional and national efforts to strengthen primary care with regard to mental health and to increase access to evidence-based interventions. DIADA is a collaborative project between a high-income country and a medium-income country that seeks to implement a model for screening, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of depression and risky alcohol use, supported by cross-cutting use of innovative technologies. Since it was launched in 2017, the DIADA project has gradually advanced in the implementation of the model at six primary care centres in four Departments of Colombia (Bogotá DC, Cundinamarca, Boyacá and Tolima).9

The implementation process and the results achieved to date with the DIADA project have prompted two-way reflections, some on GMH and its impact on the project and local models, and others on the feedback generated by real-world experience on a structured theory like GMH.

Focus on depression and alcohol abuse problems plus systematic screeningThe significant impact of depression and alcohol use disorders on the global disease burden accounts for their prioritisation as foci of mental health interventions and in the DIADA project. Global disease burden studies include the Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental [Colombian National Mental Health Survey] (ENSM) conducted in Colombia in 2015, which found a prevalence of any depressive disorder in the population of Colombia of 2.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.7–3.5).10 In addition, according to the United States Preventive Service Task Force, adults should be routinely screened for both conditions in primary care, provided that suitable infrastructure for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up is available.11,12 The prior work of the Colombian DIADA team on developing national guidelines for approaching depression and alcohol use in primary care also influenced this decision, given its thematic and methodological experience as well as its experience in training primary care professionals in mental health.13,14

Depression raises interesting cultural issues, since one may express one's personal experience of emotional malaise in terms other than "depression" — for example, "nerves", "anguish", "concern", "stress" or "tension". Therefore, screening the population of a country like Colombia with scales and categories created by high-income countries is a challenge for both research and medical practice in mental health. Below are some quotations from interviews with participants in the DIADA study exemplifying cultural considerations in the perception of depression: "… my mum and I were talking some time ago, before that appointment, about me wanting to get psychological counselling or something because I felt a little depressed…low, distracted…" (AM; male patient) "… people really think that you're just a bit 'bored', like you don't quite know what to do with yourself, but that's actually depression and that depression can make you sick" (PR; male patient) "The first thing they said when I told them that I was in a mental health programme was 'You're crazy'" (CV; female patient)

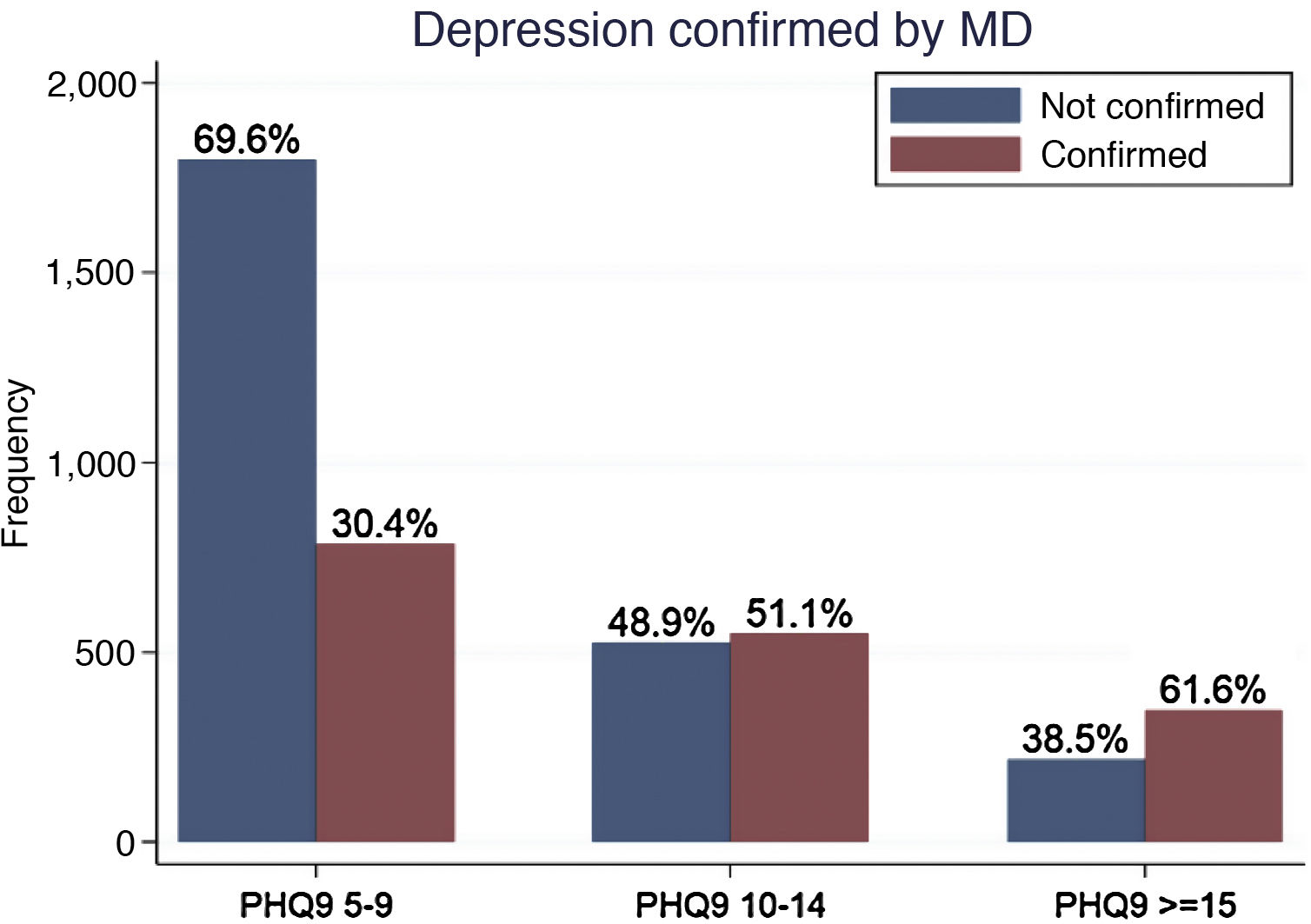

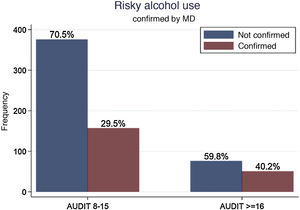

For the DIADA project, the scales chosen for depression screening were the Whooley questions,15 followed by the PHQ-9, which has been validated in the Colombian context, as well as in other Latin American countries, with studies demonstrating its usefulness both for detection of this condition and its degrees of severity and for suitable follow-up.16–18 In the DIADA project, this instrument demonstrated its practical utility as it identified symptom severity; this was reflected in the directly proportional relationship between the rate of confirmation of a diagnosis made by physicians and the score on the scale at the time of screening (Fig. 1). While on the one hand this prevents overdiagnosis and medicalisation of emotional suffering, it is also likely that the use of these scales does not reflect or detect other ways of expressing emotional suffering in the Colombian population. Table 1

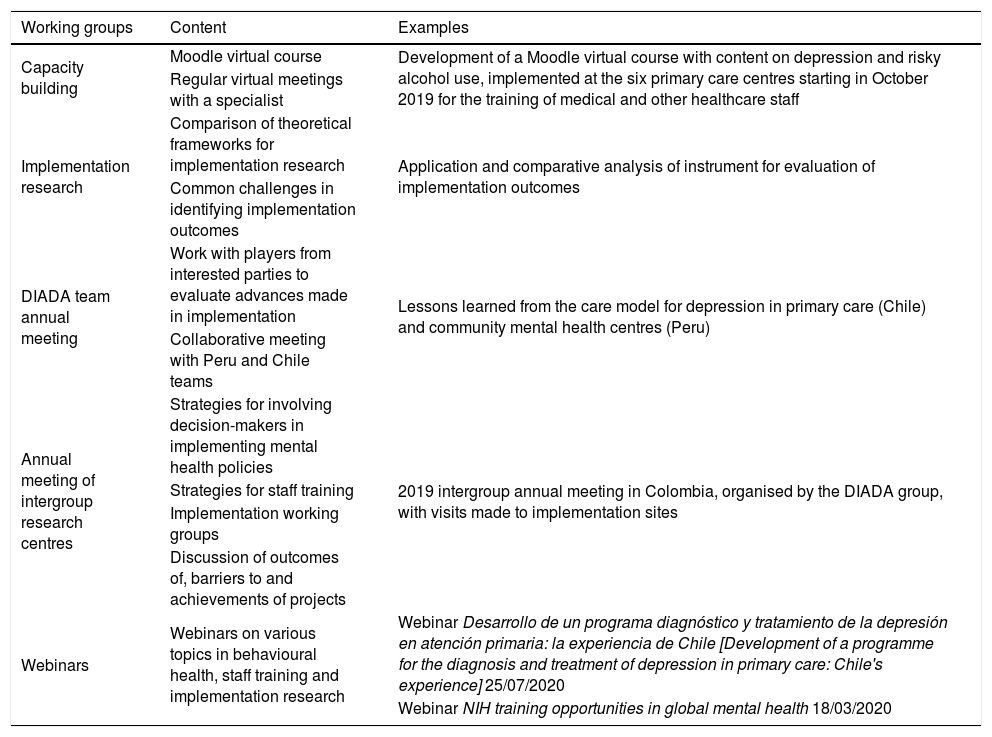

Collaborative working strategies. DIADA project.

| Working groups | Content | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity building | Moodle virtual course | Development of a Moodle virtual course with content on depression and risky alcohol use, implemented at the six primary care centres starting in October 2019 for the training of medical and other healthcare staff |

| Regular virtual meetings with a specialist | ||

| Implementation research | Comparison of theoretical frameworks for implementation research | Application and comparative analysis of instrument for evaluation of implementation outcomes |

| Common challenges in identifying implementation outcomes | ||

| DIADA team annual meeting | Work with players from interested parties to evaluate advances made in implementation | Lessons learned from the care model for depression in primary care (Chile) and community mental health centres (Peru) |

| Collaborative meeting with Peru and Chile teams | ||

| Annual meeting of intergroup research centres | Strategies for involving decision-makers in implementing mental health policies | 2019 intergroup annual meeting in Colombia, organised by the DIADA group, with visits made to implementation sites |

| Strategies for staff training | ||

| Implementation working groups | ||

| Discussion of outcomes of, barriers to and achievements of projects | ||

| Webinars | Webinars on various topics in behavioural health, staff training and implementation research | Webinar Desarrollo de un programa diagnóstico y tratamiento de la depresión en atención primaria: la experiencia de Chile [Development of a programme for the diagnosis and treatment of depression in primary care: Chile's experience] 25/07/2020 |

| Webinar NIH training opportunities in global mental health 18/03/2020 |

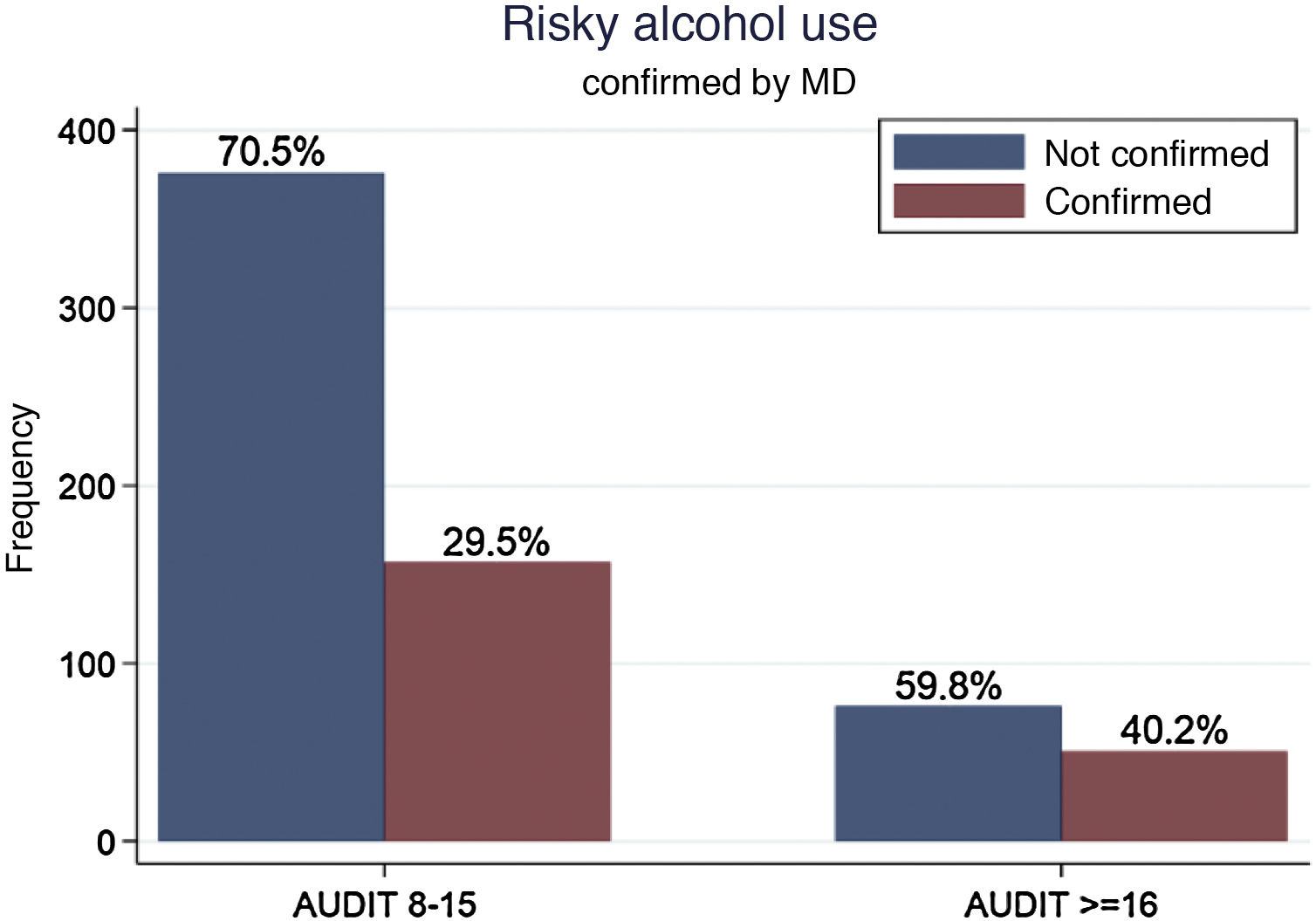

Alcohol use, for its part, presents major difficulties, and the implementation of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) does not seem to have yielded the expected results, taking Colombian national epidemiological data as a reference.10 While the ENSM showed a prevalence of excessive alcohol consumption of 21.8% in the population 18–44 years of age and 12.3% in those over 45, the DIADA study found a confirmation of risky alcohol use of just 1.8%. It is important to bear in mind that these populations are not comparable to one another, since the ENSM screened the general population and the DIADA project screened a population that sought health services for some reason (Fig. 2).

Cultural factors, as well as attitudes among people and healthcare professionals towards alcohol consumption and how it is addressed in primary care, probably played an important role in this low rate of detection. The following are a few illustrative quotations. "…Alcohol use has to do with how you were brought up. If you drink and have fun, that’s because that’s the way your dad was raised." (PR; male patient) "…for example, for very rural people, alcohol consumption is normal. They don't just buy it, they make it, they make chicha [maize liquor]… And there are people who, I don't know, drink chicha every day and it seems normal to them" (NJ; physician)

In the course of implementing the DIADA project, emphasis was placed on the new model for addressing alcohol use disorders. The new model is characterised by its focus on risk and avoidance of moralising or dichotomising patients as "alcoholic" or "not alcoholic".19 This approach also arose from collaboration with the Dartmouth team and is reflected in the translation of a video that explains the new outlook very well.20 The difficulty of addressing alcohol use reflects the near-total failure to address it in primary care in Colombia. Primary care remains focused on confirming or ruling out a diagnosis; without this ritual, it is impossible to justify the time allotted in a general medical consultation for promotion and prevention. "…That is, if a patient comes in with hypertension, the emotional or psychiatric disease part sort of gets edged out" (NJ; physician)

There is a growing body of evidence of barriers to patient access to mental health-related services.21 Recent studies have pointed to the potential of mobile app-based mental health interventions as aids in following up and treating patients with mental disorders.22,23 Considering the vast numbers of applications developed to help manage these disorders, specific aspects that make some applications better suited to patient self-management, and therefore more effective, than others have yet to be elucidated.24,25 Moreover, a major limitation in certain populations is a lack of access to such technologies due to their cost or poor network infrastructure for Internet access. This is known as the digital divide.26,27

As part of the initial phase of the DIADA project, a survey was conducted at the different medical centres of implementation. The survey found significant rates of use of smartphones among most patients at both rural and urban primary care centres, as well as local or remote Internet access.28 However, the same survey detected greater use of digital media by young people compared to older people, with 74% of patients 18–44 years of age using their smartphone for Internet browsing. In addition, patients at urban centres showed higher rates of use of their smartphones for Internet browsing (75% of patients) compared to patients at rural centres, the majority of whom did not use their mobile devices for Internet browsing (66% of patients).

In view of this, the DIADA project decided to implement a technology-supported model to screen, diagnose and treat patients in primary care. Screening involved kiosks with built-in tablets to screen patients for depression and alcohol use disorders. Screening using tablets has been widely used in different models around the world.29–31 The local team designed the kiosks, adapted the tablets and incorporated decision-making aids.

Digital aids through which scores on screening scales (PHQ-9 and AUDIT) and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of depressive disorders and alcohol use disorders could be viewed on a virtual platform optimised (diagnostic) confirmation by medical staff. For patients with a diagnosis confirmed by a physician, a supplement to prescription treatment consisted of downloading a mobile app called Laddr to their phones. The app was developed in the United States; the Colombian team adapted its language. The goal of the app is to move up a "ladder", each rung of which serves as a tool for setting goals, weighing the pros and cons of alcohol use, and managing emotions, among other things.

The knowledge generated through the experience acquired with the DIADA project included several contributions in relation to adoption of technologies in mental health. One of these was a greater understanding of the scope of and barriers to process optimisation, such as confirmation/diagnosis during a medical appointment. In the DIADA project, all patients visited the health service for a scheduled general medical appointment. They underwent screening in the waiting room and were given a piece of paper with their results to give to their treating physician, regardless of the reason for their appointment. However, patients often did not share their screening results, and physicians often did not have time to log on to the diagnostic confirmation platform, meaning that they ultimately never saw those screening results. Strategies such as linking screening to alerts integrated into the medical record system represent an option that could optimise the rate of confirmation of positive patients.

Regarding the patient self-management app, it was found that patients wanted feedback from the process. This desire was usually preceded by an inability to access in-person follow-up with psychology or psychiatry. In practice, telephone follow-up by research assistants, which was primarily intended to obtain scores for patients on corresponding scales, became a major element of treatment in many cases, despite this not being its purpose. Some participants were clear: "This is the first time they've shown an interest in me, in how I'm doing".

Although digital tools like Laddr are designed to bridge the divide in addressing disorders such as depression, they are ultimately limited by the very challenges that they attempt to address. The vast majority of available apps have not been validated with regard to treatment efficacy or adherence.32,33 Without the support of healthcare professionals, technological tools may be inadequate in individual processes.

The collaborative modelModels of depression management in the primary care context have multiple shortcomings that hinder suitable diagnosis, treatment, referral and follow-up.34 The collaborative model has arisen as a viable pathway for managing depression, a chronic disease that is poorly managed in Colombia. This model involves coordinated collaborative efforts among different healthcare professionals with the goal of helping patients to overcome their problems. In mental illness management, those healthcare professionals usually include a physician, a caseworker and a mental health specialist.35 Thus the collaborative model is ultimately "the care a patient experiences as a result of a team of primary care and behavioural health clinicians, working together with patients and families, using a systematic and cost-effective approach to provide patient-centred care for a defined population (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality)".

Despite existing evidence in favour of developing the collaborative model, multiple barriers persist in impeding its development and implementation. Notable among these are barriers to achieving active participation by the clinical staff involved, conflicting ideas among multidisciplinary team members, deficits in the training and skills of clinical staff, and heavy workloads and lack of time on the part of staff.36 On the other hand, one factor that facilitated development and implementation in the Colombian context was the existence at some implementation sites of models very similar to the collaborative model for maternal–child health.

Concerning barriers, achieving participation by medical staff was of great importance in the DIADA project implementation process. This could be seen through the Behavioural Health Integration in Medical Care (BHIMC) index. Preliminary results of BHIMC measurements have demonstrated how a lack of standardised protocols affects efforts to identify patients with behavioural disorders, and even though patients receive care regardless of whether their disease is physical or mental, a tendency to prioritise appointments related to physical disease has been seen.37 This phenomenon is not limited to institutional protocols; it is also seen in the actions and mentalities of individual healthcare professionals in Colombia.

The experience of the project in active participation by medical staff was linked to processes of training in and awareness-raising of the intervention to be made. Initially, training was provided to all medical staff at each institution. In addition, summaries were prepared of data on recruitment of patients, categorisation of patients by severity and the course of the symptoms of the patients enrolled in the study in order to improve staff participation.

Despite these strategies, barriers to participation by medical staff were strongly linked to workloads and limitations on time. A great deal of awareness-raising was achieved among staff with respect to the intervention, but if appointment times are minimal, physicians end up prioritising the initial reason for the appointment and neglecting to confirm a diagnosis of depression or an alcohol use-related disorder. The collaborative model attempts to break down this barrier by increasing "perceived efficiency" among healthcare professionals in primary care. This translates to healthcare staff perceiving greater self-efficacy in managing patients with behavioural disorders. This perceived greater self-efficacy is achieved through collaborative meetings, in which behavioural health specialists help primary care staff to improve their skills and abilities through case reviews, clinical cases, feedback on their work and solutions to unresolved matters related to the care of this specific group of patients.

Implementation researchAnother specific objective of the DIADA project was to bridge the existing divide in implementing a project within the healthcare system — a divide that stands in the way of standardising knowledge acquired through evidence-based medicine (EBM) and the suitable functioning and adoption thereof in clinical practice. The importance of implementation research, a relatively new field, led the United States National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to fund projects dedicated to this type of research, thus making the DIADA project possible (https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/organization/cgmhr/scaleuphubs/scaling-up-mental-health-interventions-in-latin-america.shtml).

Successful implementation requires the participation of the members of a multidisciplinary team who are knowledgeable about the social and cultural context, understand the care pathways that exist and have a thorough grasp of the technology or intervention to be implemented.38 Hence, the DIADA project involved the participation of professionals in psychiatry, other branches of medicine, psychology, nursing, anthropology, administration and other fields.

Another challenge in implementing a healthcare programme has to do with the political, administrative and economic entities governing the target location and population. Once implementation is attained, the final step in the research is a challenging one: to measure, in a valid and consistent manner, the specific outcomes achieved. Healthcare system players in general are not familiar with the methodology of implementation research or its particular results. In our experience within the DIADA project, we found that there were two reasons for this: the limited availability of instruments of measurement and the difficulty of adapting them to different contexts.

To overcome this challenge, the DIADA project sought literature and information from other research projects and groups. A systematic review39 and two repositories of measures related to this type of study were found.40,41 In addition, on multiple occasions, the team consulted with the hub of the Johns Hopkins University group belonging to the NIMH global research project cohort. This allowed the team to identify a tool that comprehensively captured the implementation outcomes to be measured and that furthermore had been used by research groups in medium- and low-income countries similar to Colombia.42 That tool is called Implementation Measure for Low and Middle Income Countries (IMICO). It is based on a questionnaire with eight domains, including adoption, viability, acceptance and sustainability. It was administered to patients, physicians and administrative staff at each institution.42

Collaborative learningCollaborative learning is intended to share the results and outcomes of making an intervention in different places under certain predetermined conditions. The experiences of each care centre are shared in a joint discussion in which the barriers identified by each site, the differences in outcomes of interest, the similarities between the institutions and the greatest strengths and weaknesses of implementing the model at each site are considered.43

In seeking to conduct implementation research, it is vitally important to create learning networks that facilitate and optimise the delivery of effective interventions to a particular population in as little time as possible. In the context of the DIADA project, there were both international and local learning networks. Regarding the former, international collaborative learning consisted of the 11 research hubs of the NIMH of the United States,44 groups dedicated to mental health scaling in low- and medium-income countries. The latter consisted of the primary care centres at which the project was implemented.45

In relation to international learning, all research centres made efforts to explore the different experiences and points of view of the investigators and collaborators on each team. A recent collaborative study among the hubs yielded five recommendations for breaking down these barriers, including:46

- •

Fostering career continuity among young researchers in mental health.

- •

Getting decision-makers to appreciate the value of mental health.

- •

Identifying the impact of research on policy and practice.

- •

Supporting working teams in providing evidence-based treatments.

- •

Promoting the sustainability of the programmes.

In addition to this, international collaborative learning enabled identification of important objectives not addressed as part of the DIADA project. For example, with respect to staff capacity building, the Suicide Prevention and Implementation Research Initiative (SPIRIT), implemented in India and Bangladesh for suicide prevention, was not only focused on healthcare and research staff capacity building but also dedicated to training decision-makers and community members.47 The objective of this was to provide these two social players with tools to understand the results of the study and the impact that the intervention could end up having on the local population. Although the DIADA project worked with decision-makers on a national level and made efforts to prepare policy briefs for decision-makers, one point to take into account in future efforts is the training of community members or peers to strengthen the project in the community context.

An additional international collaborative learning component consisted of dialogue among implementation projects in Colombia, Peru and Chile. This dialogue occurred through talks and webinars in which each centre's experience was shared with team leaders and members in other countries, with space left for questions and discussion at the end of each session. These spaces enabled identification of shared economic, political and social obstacles in different countries with the shared characteristic of all being in Latin America.

The healthcare systemUltimately, the implementation of a project in mental health is closely bound to the context of that implementation. For this reason, we sought to reflect on the health system in Colombia, its organisation and its distribution across the country, as well as the main barriers to and facilitators of an experience like the DIADA project.

To start, mention must be made of Law 100 of 1993 creating the Sistema Seguridad Social Integral [Colombian Comprehensive Social Security System] with three main objectives: demonopolisation of health together with greater management and supervision; universal coverage in pursuit of solidarity and support between rich and poor sectors of society; and sustainability and competitiveness with the user responsible for choosing his or her own service provider.48–50 These three changes were intended to transform the prior healthcare model in which the most affluent received what they could afford and the less privileged classes received whatever charity was doled out to them.51

The greatest impact of the law was an increase in healthcare coverage on a national level from 56.9% in 1997 to 90.8% in 2012,52 with "coverage" being defined as the number of people who were enrolled in the system (which does not necessarily imply that they had access to the system). This was reflected in the DIADA project, in the option for people to make use of local health services without incurring direct costs. However, this ensured genuine access not to mental health in primary care, but to general medical care.

The decentralisation of the health sector brought with it greater opportunities to manage and supervise public expenditure, reflected in an increase in internal and external audits.51 However, this carried two negative consequences. The first was in relation to communication and consensus: in the course of planning, decision-making, resource allocation and operations, each level of the system put its own interests first. For this reason, projects like the DIADA project are subject to lengthy bureaucratic processes that, in the best-case scenario, lead to fluid implementation of new care models.

The second negative consequence was due precisely to this very autonomy afforded to each of the actors within the system — Entidades Promotoras de Salud [Health Promoting Entities] (EPSs), Instituciones Prestadoras de Servicios de Salud [Health Providing Institutions] (IPSs), supplementary plans, special plans, etc. — as it impedes decision-making and establishment of practices on a national level, thus delaying effective dissemination and implementation of strategies that reach all or most of the population of the country.51,53 The DIADA project had patients at six primary care institutions; each of these centres (IPSs) cared for patients with multiple EPSs, which provide the same general services, but with different care pathways and providers. This was reflected in patient appointment lengths, appointment openings, numbers of specialists and different administrative processes, even within a single IPS, and in the overall support for the project provided by the affiliated institutions.

At the same time, the political and economic history of Colombia has been seen to be closely tied to the national armed conflict. The health sector is no stranger to this union. Healthcare professionals know first-hand that the armed conflict in Colombia has caused countless health problems classified as "injuries due to external causes" (injuries caused by firearms or sharp objects, burns, drownings, etc.).54 In addition, studies have been conducted showing high rates of morbidity due to mental health disorders associated with experiences of violence, with many populations in the country ultimately affected.55 The existence of much sociopolitical and geographic fragmentation is also important in this regard, since this violence, and the consequences thereof, have not affected all the regions of the country equally in terms of duration or volume.

Colombia, a country of many contradictions classified in 2020 by the International World Bank as an upper-middle income country,56 offers proof that a country's health system and population healthcare maintain a close relationship to that country's political, social, cultural and economic history. However, these relationships between health and socioeconomic development do not always go in the same direction, since there are vast discrepancies in access among different population groups in some countries classified as high-income countries, despite their large quantities of economic resources and technological and scientific development.

ConclusionsThe DIADA project, as an example of a collaborative mental health effort, successfully implemented screening for depression and alcohol use at various primary care centres in Colombia. To achieve this objective, implementation studies must take into consideration the complexity of the context, which determines many of the strategies pursued and outcomes achieved.

In implementation research, the complexity of interventions and the importance of context largely determine strategies and eventual outcomes. Incorporation of mental health care requires joint evaluation of social, political, healthcare system-related, cultural, economic and other factors. Experiences of similar programmes in other countries, despite differences among them, share methodological and research-related aspects. Some tools and theoretical frameworks derived from global mental health efforts may be applied in dissimilar contexts.

Local learning, for its part, feeds into global mental health efforts when done with suitable implementation research methodology, with evaluation of impacts and outcomes as well as circulation and appraisal of results. Such was the case in the DIADA project, in which the adaptation to the Colombian context of the use of technologies in detection, evaluation and management of mental health problems represented an example of local contributions to addressing a shared global problem. Learning and collaborative research networks are essential for making advances in mental health in diverse population groups.

FundingThe research reported in this publication was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) of the United States with Grant Number 1U19MH109988 (Multiple Principal Investigators: Lisa A. Marsch, PhD, and Carlos Gómez-Restrepo, MD, PhD). The content solely reflects the opinions of the authors, who do not represent the views of the NIH or the federal government of the United States.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Uribe-Restrepo JM, Gómez-Ayala MC, Rosas-Romero JC, Cubillos L, Cepeda M, Gómez-Restrepo C. Salud Mental Global y el Proyecto DIADA. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:13–21.