The aim of this research is to describe the knowledge of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among primary school teachers through interviews concerning general information, symptoms/diagnosis and treatment, in addition to perceived self-efficacy.

MethodsA cross-sectional, descriptive, population-based study was carried out, involving 62 teachers from public schools in the municipality of Sabaneta. The teachers were evaluated by the Spanish adaptation of the Knowledge of Attention Deficit Disorders Scale, a 36-item estimation scale with three response options (true, false and don’t know).

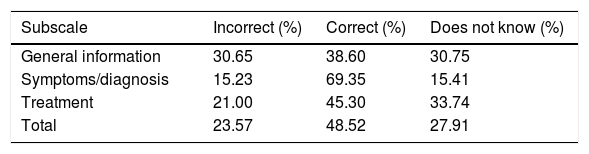

ResultsTeachers correctly answered just under half of all the items in the questionnaire (48.52%). Specifically, the most correct answers were on the symptoms/diagnosis subscale (69.35%), followed by the treatment subscale (45.30%) and finally the general information subscale (38.60%).

ConclusionsThe data obtained underlines the need for initiatives to be implemented in this area to ensure that it is reflected in new teaching techniques that facilitate the learning and development of children who suffer from the disorder.

La presente investigación tiene como propósito describir los conocimientos de los docentes de básica primaria sobre el trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH), mediante entrevistas sobre información general, síntomas/diagnóstico y tratamiento, además de la autoeficiencia percibida.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio descriptivo transversal de tipo poblacional, en el que participaron 62 docentes de colegios públicos del municipio de Sabaneta. Los maestros fueron evaluados mediante la adaptación española de la Knowledge of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (KADDS), una escala de estimación compuesta por 36 ítems de 3 alternativas de respuesta (verdadero, falso y no sé).

ResultadosLos docentes contestaron correctamente a poco menos de la mitad de todos los ítems del cuestionario (48,52%). En concreto, fue en la subescala de síntomas/diagnóstico en la que tuvieron más aciertos, con un 69,35%, seguida de la subescala de tratamiento (45,30%) y, finalmente, la de información general (38,60%).

ConclusionesSegún los datos obtenidos, se ratifica la necesidad de realizar intervenciones en este tema, para que esto se vea reflejado en nuevas técnicas de enseñanza que faciliten el aprendizaje y el desarrollo de los niños que padecen el trastorno.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common disorder in child psychiatry. It is characterised by a pattern of symptoms of inattentiveness, hyperactivity and impulsiveness, which are more severe and occur with greater frequency than would be expected for children of the same age.1 Worldwide, the prevalence is reported to be 5.29%.2 In Colombia, studies such as that by Pineda et al.3 found the prevalence to be 11.3%, while in Sabaneta, according to Cornejo et al.,4 it is as high as 20.4%. ADHD usually begins during the school years, hence the reason this stage is so important for identifying affected children, and it is precisely the teachers who most often detect it.5 A literature review with regard to knowledge about ADHD among teaching staff shows that, in general, training in this area appears to be insufficient. For example, in the study by Jarque et al.,6 teachers responded correctly to 42.65% of the items, showing that the degree of knowledge about the subject is not very high. In line with that research, the aim of this study was to describe the knowledge of ADHD among primary school teachers in public schools in the town of Sabaneta in June 2016.

Material and methodsA cross-sectional, descriptive, population-based study was conducted with all primary school teachers in public schools in the town of Sabaneta. The teachers were assessed using the Spanish adaptation of the Knowledge of Attention Deficit Disorders Scale (KADDS), an estimation scale consisting of 36 items with three response options (true, false and don’t know). The items are grouped into three subscales: (a) symptoms/diagnosis of ADHD (9 items); (b) general information about the nature, causes and repercussions of ADHD (15 items); and (c) treatment of ADHD (12 items). The scale also seeks to determine whether or not the teacher has a specialist area, diploma or degree; whether or not they have received training on the disorder, and whether or not they have any experience in the educational field or in the management of children with ADHD. The reliability of the instrument for each of the categories (a–c) is 0.74–0.77. For the whole scale, it is 0.89.7 To assess perceived self-efficacy, teachers answered the following question, using a 7-point Likert scale: To what extent do you consider that you can effectively teach a child with ADHD?

To collect the information, a day was arranged with the head teachers of each institution for the teachers to complete the survey. On the agreed day, the teachers were gathered in a room, where they were given the informed consent form and the survey. Before completing the survey, the purpose of the project and the correct way to respond to the items were explained.

Statistical analysisA univariate analysis was performed; the qualitative variables were analysed by frequency and percentage, and the quantitative variables by measures of central tendency and dispersion.

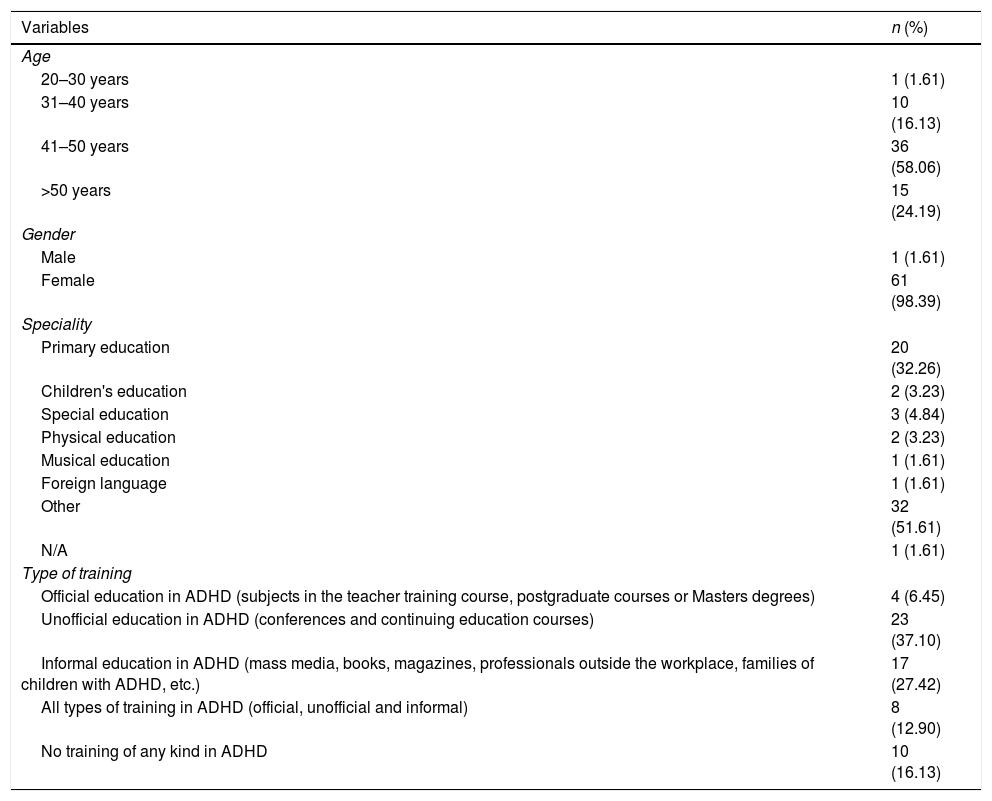

ResultsOf a total of 75 teachers involved in primary education in the public sector, 62 participated in the study (participation rate 82.7%). Of these, 58.06% were aged 41–50 (mean, 45.97±7.61) and 98.39% were female. With regard to specialist training, 32.26% had specialised in primary education and 51.61% in other areas such as mathematics, environmental education, play, etc. In addition, 80.65% reported having over 10 years of experience in teaching; five teachers did not answer this question. As far as working with children with ADHD was concerned, 58.68% (37) had over 10 years of experience; four teachers did not answer this item (Table 1).

Sociodemographic and training characteristics of teachers in the public schools of Sabaneta, as of June 2016 (n=62).

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 20–30 years | 1 (1.61) |

| 31–40 years | 10 (16.13) |

| 41–50 years | 36 (58.06) |

| >50 years | 15 (24.19) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 1 (1.61) |

| Female | 61 (98.39) |

| Speciality | |

| Primary education | 20 (32.26) |

| Children's education | 2 (3.23) |

| Special education | 3 (4.84) |

| Physical education | 2 (3.23) |

| Musical education | 1 (1.61) |

| Foreign language | 1 (1.61) |

| Other | 32 (51.61) |

| N/A | 1 (1.61) |

| Type of training | |

| Official education in ADHD (subjects in the teacher training course, postgraduate courses or Masters degrees) | 4 (6.45) |

| Unofficial education in ADHD (conferences and continuing education courses) | 23 (37.10) |

| Informal education in ADHD (mass media, books, magazines, professionals outside the workplace, families of children with ADHD, etc.) | 17 (27.42) |

| All types of training in ADHD (official, unofficial and informal) | 8 (12.90) |

| No training of any kind in ADHD | 10 (16.13) |

ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

The teachers correctly answered slightly fewer than half the items in the questionnaire as a whole (48.52%). Specifically, the most correct answers were on the symptoms/diagnosis subscale (69.35%), followed by the treatment subscale (45.30%) and the general information subscale (38.60%) (Table 2).

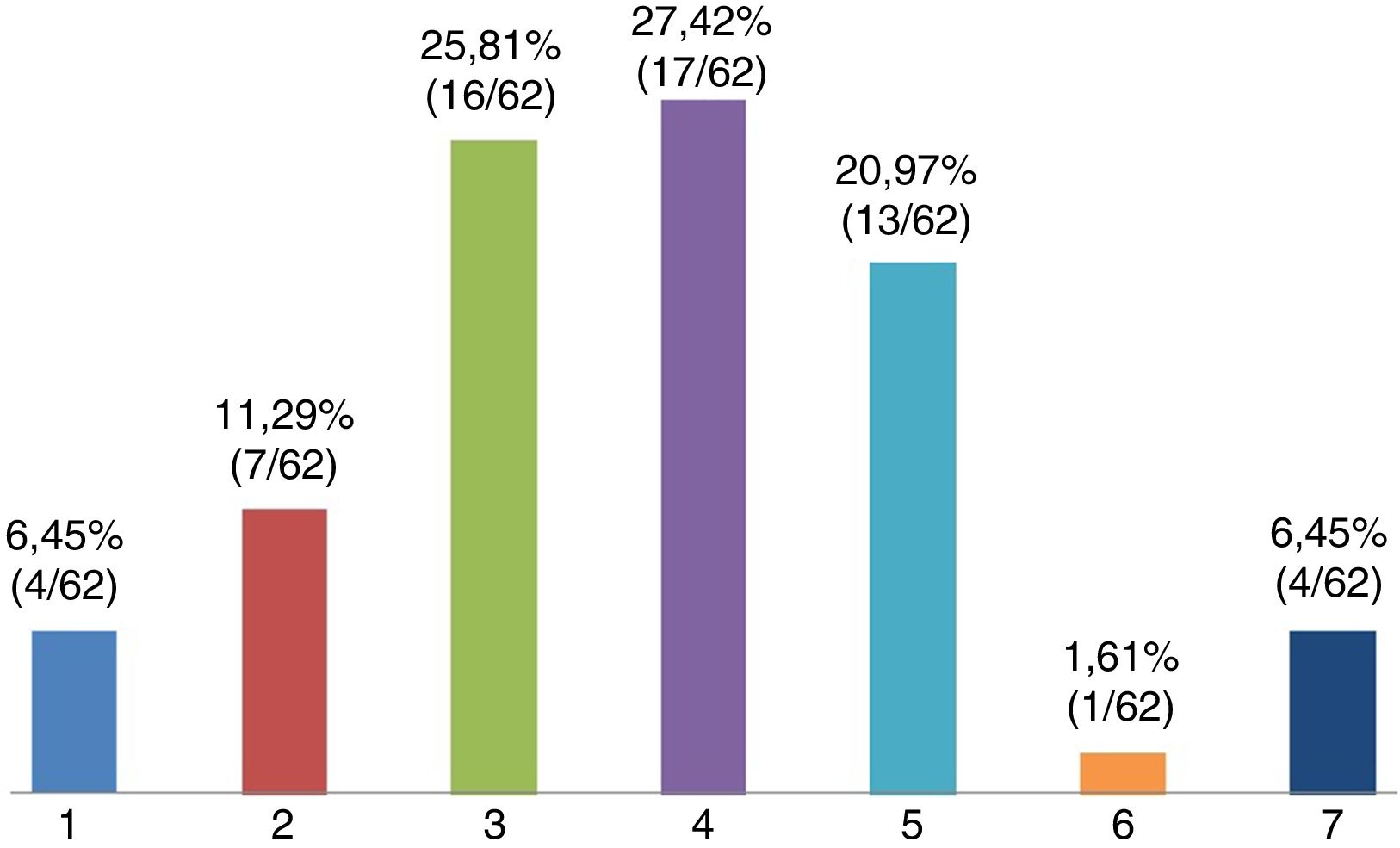

For the teachers’ perceived self-efficacy with regard to ADHD, a score of 4 was the most common (27.42%), followed by 3 (25.81%). It should be noted that only a small percentage of teachers (6.45%) felt fully prepared to teach children with ADHD (they scored 7 points on the perceived self-efficacy scale) (Fig. 1).

DiscussionIn this study, our aim was to analyse knowledge about ADHD and perceived level of self-efficacy among primary school teachers in public schools in the town of Sabaneta.

In terms of level of knowledge about ADHD, our results are similar to those obtained by Jarque et al. (Spain)6 and Sciutto et al. (United States).8 Jarque et al.6 reported 42.65% of correct answers in the scale overall. The teachers studied by Sciutto et al.7 correctly answered 47.81% of the questions, and the most correct answers were also obtained in the symptoms/diagnosis subscale.

However, other studies had higher rates of correct answers. For example, Barbaresi and Olsen9 (USA) reported 77% correct answers, while Kos et al.10 (Australia) reported 60.7%, and Jerome et al. (Canada)11 reported 77.5%. According to Kos et al.,10 these differences may be due to the fact that some studies offered only two possible response options (true or false), which may have biased the results.

To sum up, the most significant results of the study indicate that teachers have little knowledge about ADHD, as they answered fewer than half of the items on the KADDS correctly. This figure is surprising considering that 83.87% of teachers reported having received some type of training on ADHD. Teachers go predominantly to unofficial sources of information to expand their knowledge about the disorder. Bearing in mind that any type of training for increasing understanding of ADHD is valid, taking measures that lead teachers to be more interested in receiving such training would be an excellent step. As Soroa et al.12 state, the official, formal education provision could be broadened (e.g. increase the presence of ADHD in the curriculum of university teacher training courses), unofficial methods could be reinforced (e.g. increasing the number of conferences on the subject), and last but not least, due to the tendency of teachers to resort to informal sources, provide them with strategies that help them identify good quality information provided by such sources. Moreover, it would be invaluable if any proposed training were to take into account the different functions that educators can exercise in relation to children with ADHD, in view of the fact that the early detection of the disorder is not their only task.

The perceived self-efficacy reported by teachers concerning ADHD is consistent with the results obtained on the scale; 43.55% did not believe they had the ability to teach a child with ADHD, which correlated with their poor performance on the scale.

In general terms, the instrument used to assess teachers’ knowledge of ADHD has adequate psychometric properties, according to validations of the study by Jarque et al. (Spain).6,7 Nevertheless, it should be pointed out how small the sample was. It would be interesting to extend the study to other local areas, as well as to other regions of the country, and be able to observe the differences and similarities in the knowledge of teaching staff about ADHD in different geographical locations.

Lastly, we should point to limitations in the study that need to be taken into account in future research. First of all, more detailed information should be obtained from the subjects’ training and experience data in order to establish a bivariate analysis, given the importance that variables such as ADHD training and experience with hyperactive children have been shown to have. A second limitation is related to the size of the sample; similar studies have had a larger number of participants, from 150 to 400 teachers. However, we should clarify that in this study all the public schools were covered as we sought to represent all the teachers in these institutions. It would also be interesting to conduct studies in different populations to ensure the external validity of the results obtained and to identify whether or not there are significant differences in the level of knowledge of teachers in ADHD between this region and other regions of the country.

Last of all, we would conclude that:

- ∘

According to the data obtained, knowledge of ADHD among the teachers surveyed did not reach 50%. This confirms the need for ADHD-based initiatives, to ensure that it is reflected in new teaching techniques that facilitate the learning and development of children who suffer from the disorder.

- ∘

The teachers were very honest about their knowledge of ADHD in the assessment, as their performance in the survey was consistent with the fact that they considered themselves little prepared to teach children with this disorder.

- ∘

This study is pioneering here in Colombia and it signifies a great advance in ADHD, which is of interest not only for the area of healthcare, but also for the education sector, and will hopefully have a positive impact on this vulnerable population.

The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols implemented in their place of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Firstly, we thank God for allowing us to successfully complete this project. We thank our families who, through their effort and support, have made this path of becoming doctors possible. We would also like to thank the educational institutions for their participation and the Education Secretariat for the municipal area of Sabaneta, headed by Yuly Quintero Londoño, as without them, we would not have been able to complete this project. We would also like to express our special thanks to our subject advisers, Dr Ramón Lopera and Dr Wilson Weir, for their valuable contributions and collaboration.

Please cite this article as: Padilla AM, Cuartas DB, Henao LF, Arroyo EA, Flórez JE. Conocimientos sobre TDAH de los docentes de primaria de colegios públicos de Sabaneta, Antioquia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2018;47:165–169.

Research presented at the 28th Asociación Médica Sindical Colombiana (ASMEDAS) National Congress of General and Social Medicine, Medellín, Antioquia, Colombia, 6 October 2016.