The Mexican health-care system is a mixture of governmental and private institutions. The osteoporosis screening algorithm has a multiple case start-point, the most common being medical referral; however, self-screening is available where patients can arrange a bone densitometry themselves.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of self-screening for osteoporosis and osteopenia among a Mexican population.

Materials and methodsA retrospective observational study was performed as a secondary outcome from an institutional cohort of patients who attended an osteoporosis center. We divided the cohort into two groups: self-referred patients and medical-referred patients.

ResultsThe overall prevalence of osteoporosis between the two groups was 1160 (self-referred n=44; 29.5% vs medical-referred n=227; 22.5%; p=.057) (OR (Odds Ratio); 95% CI (Confidence Interval): 1.44; .98–2.12) and the prevalence of osteopenia was (n=122; 81.9% vs n=811; 80.2%; p=.633) (OR (Odds Ratio); 95% CI (Confidence Interval): 1.11; .71–1.73).

ConclusionThere was no statistical difference between the self-referred and the medically referred patients in the overall diagnosis of osteoporosis and/or osteopenia. Nevertheless, the incidence of osteoporosis and osteopenia as an outcome for the self-referred patients was not lower than that of those with a medical referral.

El sistema de salud mexicano es una mezcla de instituciones gubernamentales y privadas. El algoritmo de tamizaje de osteoporosis tiene diferentes sistemas de referencia, siendo el más común la referencia médica; sin embargo, existe la posibilidad de un escenario de autoevaluación en el que los pacientes deciden hacerse una densitometría ósea por sí mismos.

ObjetivoEl objetivo de este estudio es evaluar el impacto del autoexamen de osteoporosis y osteopenia en población mexicana.

Materiales y métodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio observacional retrospectivo como resultado secundario de una cohorte institucional de pacientes que acudieron a un centro de osteoporosis. Dividimos la cohorte en 2 grupos: pacientes autorreferidos y pacientes referidos por el médico.

ResultadosLa prevalencia global de osteoporosis entre los 2 grupos fue de 1.160 (autorreferencia n=44; 29,5% vs. médico-referencia n=227; 22,5%; p=0,057) odds ratio; intervalo de confianza del 95%: 1,44; 0,98-2,12). Y la prevalencia de osteopenia fue n=122; 81,9% vs. n=811; 80,2%; p=0,633 odds ratio; intervalo de confianza del 95%: 1,11; 0,71-1,73.

ConclusiónNo hubo diferencia estadística entre pacientes autorreferidos y los de decisión médica en el diagnóstico global de osteoporosis u osteopenia, sin embargo, la incidencia de osteoporosis y osteopenia como resultado de los pacientes autorreferidos no fue inferior a la de los pacientes con remisión médica.

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture.1,2

The prevalence of osteoporosis or low bone mass at either the femoral neck or lumbar spine has been shown to vary by ethnicity. The age-adjusted prevalence of osteoporosis in the United States is higher among Mexican American women (26%),3 and in Mexico, it is estimated that 1 in 12 women and 1 in 20 men will have a hip fracture after their 50 years.4

Osteoporosis may lead to several health complications such as bone fractures, from which hip fracture is one of the most clinically relevant and economically catastrophic.5 The economic burden of all the osteoporotic hip fractures in Mexico is estimated to be more than US$ 97 million per year.5,6

As in many other countries, the algorithm for osteoporosis screening has multiple case start-points, most commonly by physician's referral; however, patient self-screening is possible. For example, patients in Mexico may decide to get a bone densitometry (DXA) by themselves, because the Mexican health-care system is a mixture of governmental (social security institutions, social assistance for non-employed) and private institutions.7 As a major public health problem therefore, it is important an early diagnosis in self-referred or medical-referred patients for timely management. As such, little is known about the differences of individual's osteoporosis and osteopenia by screening referral mechanism (physician referral or self-referral) in Mexico. The aim of this study was to investigate differences in osteoporosis and osteopenia diagnosis by referral mechanism (medical vs self-referral).

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective and observational study from a sample of 1160 (of 1854 eligible) individuals without a diagnosis of osteoporosis or osteopenia, who attended an osteoporosis center to get their first densitometry irrespectively of their referral mechanism. Data collection was conducted between April 1st and August 1st of 2015. We excluded patients with past medical history of osteoporosis and/or osteopenia, or under active medication for these conditions.

MeasuresThe main outcomes of this study were osteopenia and osteoporosis. All patients were evaluated using the measurement of central bone mineral density using the HOLOGIC® device at the UANL University Hospital in Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico. Bone densitometry (DXA) results were evaluated and categorized as osteoporosis, osteopenia, or normal bone mineral density according to the 1994 WHO (World Health Organization) study group criteria.2

Our main exposure was a binary indicator of mode of referral (medical and self). We asked patients whether the decision of getting a bone densitometry (DXA) was due to physician's referral or by their own decision.

We included information on demographic and clinical variables, such as age, gender, active smoking, alcohol consumption greater than 3IU, self-referred diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, epilepsy, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Statistical analysisWe used Pearson Chi-Square test of proportions to compare categorical variables between groups Variables that were continuous were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For those variables that were normally distributed, we used Student T tests to compare differences between mode of referral groups. Similarly, for variables with no evidence of being normal distributed, we used Mann–Whitney U to test for differences between mode of referral groups. To estimate the associations between mode of referral, osteoporosis, and osteopenia (Table 2), we computed crude odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) using logistic regression for each bone site (femoral, hip, and vertebral). All analyses were performed using the software SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM Corp; Armonk, NY).

Results1160 patients were evaluated 1132 (97.3%) were female. The proportion of patients who reported being referred by a physician for DXA were 1011 (87.15%) and 149 (12.84%) were self-referrals. Physician referrals were more frequently done by Ob/Gyn (n=211; 23.6%) and Rheumatology (n=177; 19.8%) specialists followed by General Practitioners (n=103; 8.9%), Endocrinology (n=101; 8.7%), Orthopedic (n=60; 5.2%), Internal Medicine (n=49; 4.2%) and Family Medicine (n=43; 3.7%).

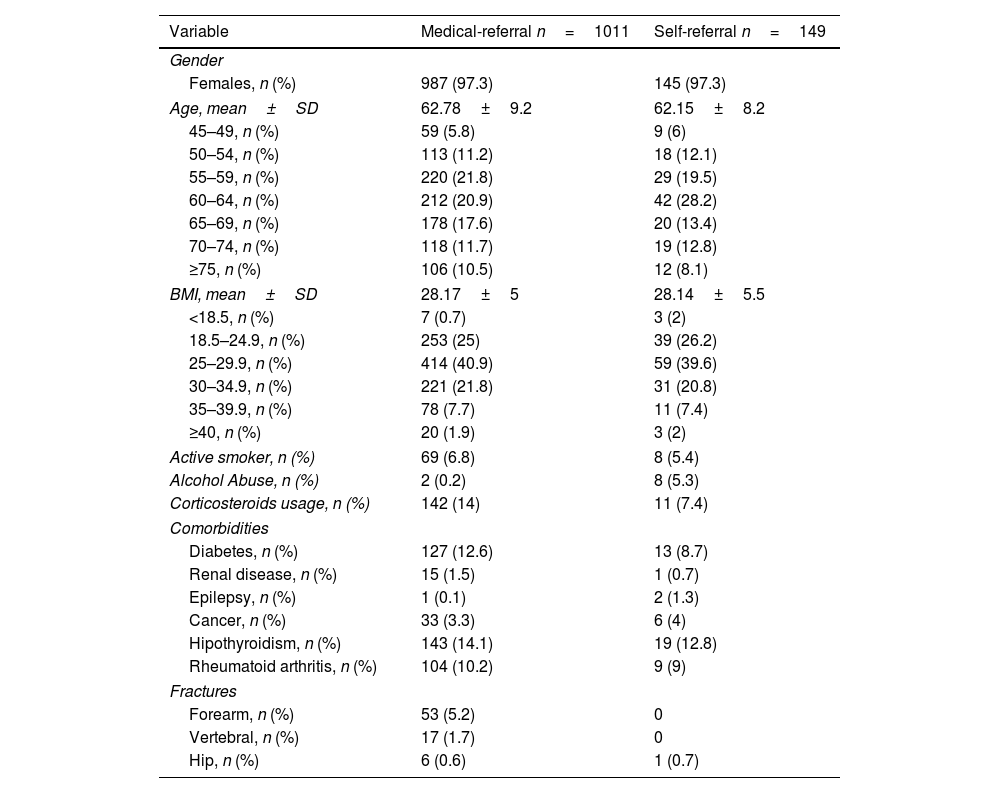

Demographics and clinical characteristics of individuals in our sample are described in Table 1 and compared by mode of referral. Overall, we found no statistically significant differences between referral group on clinical and demographic characteristics, except for corticosteroid usage, which was statistically significant higher in the physician referral group compared to the self-referral group (14% vs 7.4%; p=0.025).

Sample characteristics.

| Variable | Medical-referral n=1011 | Self-referral n=149 |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Females, n (%) | 987 (97.3) | 145 (97.3) |

| Age, mean±SD | 62.78±9.2 | 62.15±8.2 |

| 45–49, n (%) | 59 (5.8) | 9 (6) |

| 50–54, n (%) | 113 (11.2) | 18 (12.1) |

| 55–59, n (%) | 220 (21.8) | 29 (19.5) |

| 60–64, n (%) | 212 (20.9) | 42 (28.2) |

| 65–69, n (%) | 178 (17.6) | 20 (13.4) |

| 70–74, n (%) | 118 (11.7) | 19 (12.8) |

| ≥75, n (%) | 106 (10.5) | 12 (8.1) |

| BMI, mean±SD | 28.17±5 | 28.14±5.5 |

| <18.5, n (%) | 7 (0.7) | 3 (2) |

| 18.5–24.9, n (%) | 253 (25) | 39 (26.2) |

| 25–29.9, n (%) | 414 (40.9) | 59 (39.6) |

| 30–34.9, n (%) | 221 (21.8) | 31 (20.8) |

| 35–39.9, n (%) | 78 (7.7) | 11 (7.4) |

| ≥40, n (%) | 20 (1.9) | 3 (2) |

| Active smoker, n (%) | 69 (6.8) | 8 (5.4) |

| Alcohol Abuse, n (%) | 2 (0.2) | 8 (5.3) |

| Corticosteroids usage, n (%) | 142 (14) | 11 (7.4) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 127 (12.6) | 13 (8.7) |

| Renal disease, n (%) | 15 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) |

| Epilepsy, n (%) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (1.3) |

| Cancer, n (%) | 33 (3.3) | 6 (4) |

| Hipothyroidism, n (%) | 143 (14.1) | 19 (12.8) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis, n (%) | 104 (10.2) | 9 (9) |

| Fractures | ||

| Forearm, n (%) | 53 (5.2) | 0 |

| Vertebral, n (%) | 17 (1.7) | 0 |

| Hip, n (%) | 6 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) |

SD: standard deviation.

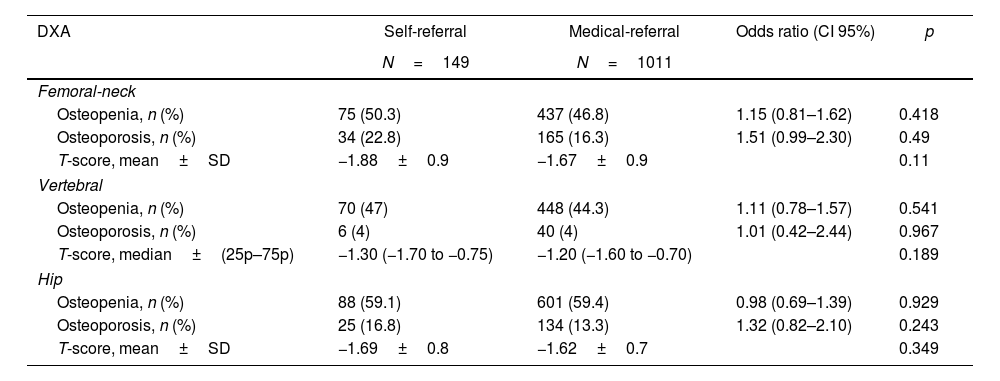

The pooled prevalence of osteoporosis among the two groups was 29.5% (95% CI=22.20–36.85) and 22.5% (19.88–25.02), respectively (OR=1.44 [95% CI=0.98–2.12]; p=0.057). The pooled prevalence of osteopenia among the two groups was 81.9% (75.69–88.06) and 80.2% (77.76–82.67) respectively (1.11 [0.71–1.73]; p=0.633). The diagnosis was also clustered by zone (Femoral neck, Vertebral, Hip) with no statistical difference among them. The summary of these findings is enlisted in Table 2.

Osteoporosis & osteopenia incidence among groups.

| DXA | Self-referral | Medical-referral | Odds ratio (CI 95%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=149 | N=1011 | |||

| Femoral-neck | ||||

| Osteopenia, n (%) | 75 (50.3) | 437 (46.8) | 1.15 (0.81–1.62) | 0.418 |

| Osteoporosis, n (%) | 34 (22.8) | 165 (16.3) | 1.51 (0.99–2.30) | 0.49 |

| T-score, mean±SD | −1.88±0.9 | −1.67±0.9 | 0.11 | |

| Vertebral | ||||

| Osteopenia, n (%) | 70 (47) | 448 (44.3) | 1.11 (0.78–1.57) | 0.541 |

| Osteoporosis, n (%) | 6 (4) | 40 (4) | 1.01 (0.42–2.44) | 0.967 |

| T-score, median±(25p–75p) | −1.30 (−1.70 to −0.75) | −1.20 (−1.60 to −0.70) | 0.189 | |

| Hip | ||||

| Osteopenia, n (%) | 88 (59.1) | 601 (59.4) | 0.98 (0.69–1.39) | 0.929 |

| Osteoporosis, n (%) | 25 (16.8) | 134 (13.3) | 1.32 (0.82–2.10) | 0.243 |

| T-score, mean±SD | −1.69±0.8 | −1.62±0.7 | 0.349 | |

DXA: dual X-ray absorptometry; SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence intervals.

We assessed differences in osteoporosis and osteopenia detection by mode of referral in a Mexican population attending an osteoporosis center. Among medical referrals, 8 categories for medical specialties were compared against the self-referral. It is interesting to know that the self-referral modality (n=149; 12.84%) represents the 3rd more common referral in this cohort, only surpassed by the Ob/Gyn (n=211; 23.6%) and the Rheumatologist (n=177; 19.8%). The difference in the screening rates between groups was not statistically significant. Similarly, the odds of getting an osteoporosis and/or osteopenia diagnosis among the self-care group was similar to the medical-referral group. This is interesting because even with a larger group and even combining all the medical specialties together, the diagnostic incidence was not inferior to this group, indeed the prevalence was greater in the self-referred patients.

Our study also showed that the prevalence among newly diagnosed patients was different than that reported in previous studies. For example, the prevalence of osteoporosis and osteopenia is lower than that reported in other large studies such as FRAVO with an overall osteoporosis and osteopenia prevalence of 50.2% and 31.8% respectively.8 On the other hand, the prevalence of osteoporosis in Mexican American women in the U.S. and in the Iranian general population was lower than the one we reported (26% and 11.7%, respectively).3,9 The higher prevalence of osteoporosis and osteopenia shown in our study could be the result of the structure of the Mexican health-care system a mixture of governmental and private institutions. Unlike Mexico, healthcare systems in other countries limit the ability of performing tests like a densitometry without a medical referral. Thus, densitometry by self-referral could lead to higher prevalence of osteoporosis and osteopenia by capturing under-detected osteoporosis and osteopenia cases.

A previous study estimated that in 2050, 37% of Mexican population will be over 50 years old and 14% will be 70 years old.10 The overall costs associated with hip-fractures in 2006 surpassed the 97 million USD an estimated individual cost per-event of 4365.5 USD.5 This highlights how people who attend a healthcare institution by self-decision may be a cost-saving approach by preventing future worst outcomes related to fractures.

We found higher prevalence of forearm and vertebral fractures among the medical-referred group than the self-referred group. Past medical history for fractures could lead to higher awareness of risk of fracture, which could prompt seek early medical evaluation, and bone screening referral by a physician. Previous studies have reported associations between risk of fracture awareness and past medical history of fractures. A cohort in Brazil found that 75% of participants had misconceptions (e.g., low self-awareness) about their risk of fracture.11 Those with good knowledge about their risk of fracture were patients with a prior diagnosis of osteoporosis or patients with a history of fractures in the postmenopausal age. Older age was also associated with inadequate knowledge of osteoporosis and risk of fracture among.12–17 To our knowledge, similar studies have not been conducted in Latin America. Further research should explore reasons other than pain to seek medical attention for osteoporosis and osteopenia.

Limitations are noted. First, our sample size was a convenience sample of people who attended an osteoporosis center to get their first densitometry independent of referral mechanism and may incur in power issues. Our analysis was exploratory in nature and future prospective studies are needed to clarify the relationship between different modes of referral, bone health (osteoporosis and osteopenia) and risk of fractures. Risk factors for osteoporosis and osteopenia were self-reported and nondifferential measurement error could be present. Our study also has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study in Latin America that explores differences in screening rates for osteoporosis and osteopenia by mode of referral that is reflective of how patients seek medical attention, both by physician referral and self-referral.

Importantly, we do not advocate to change the current diagnosis algorithm of osteopenia and osteoporosis. However, important questions remain about the differences observed between groups. For example, what prompts a patient to believe they have osteoporosis and undergo screening by self-decision? A wide array of reasons like cultural notions of disease and health are plausible and these may be worth exploiting in further studies.

ConclusionThere were no difference between self-referred patients and those referred by a physician in the overall diagnosis of osteoporosis and/or osteopenia. Nevertheless, cultural notions of disease may be a crucial element for osteoporosis self-screening in our population, which may lead to levels of disease detection comparable to their physician-initiated screening.

Availability of data and materialAll data available.

Code availabilityThe authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

FundingNo funding was received for this protocol.

Conflicts of interestDavid Vega Morales, Andrés H. Guillén Lozoya, Luis E. Segura, Jorge A. Hermosillo Villafranca, Pedro A. García Hernández, Brenda Roxana Vázquez Fuentes, Alejandro Garza Alpirez and Mario A. Garza Elizondo declare that they have no conflict of interest.

None.