Interstitial Lung Disease Associated with Autoimmune Diseases

Más datosInterstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) was defined for research purposes as interstitial lung disease (ILD) associated with features of autoimmunity without diagnosed rheumatic disease (RD). Since publication of the IPAF criteria in 2015, there have been multiple studies of IPAF. However, much remains unknown regarding pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatment in IPAF. This narrative review details the history and classification of IPAF, lists challenges associated with classifying patients as IPAF, and explores the prevalence, epidemiology, and presentation of IPAF. We also examine prognosis and important features determining IPAF clinical course, outline pathogenesis, and review treatment strategies.

La neumonía intersticial con características autoinmunes (interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features [IPAF]) se definió, para fines de investigación, como enfermedad pulmonar intersticial (EPI) con hallazgos de autoinmunidad, sin evidencia de enfermedad reumática (ER) diagnosticada. Desde la publicación de los criterios de clasificación de IPAF en el año 2015, se han venido realizando múltiples estudios acerca de esta enfermedad. Sin embargo, aún queda mucho por conocer sobre la patogénesis, el pronóstico y el tratamiento de la IPAF. Esta revisión narrativa detalla la historia y la clasificación de la IPAF, enumera los desafíos asociados con la clasificación de los pacientes como IPAF y explora la prevalencia, la epidemiología y las manifestaciones clínicas de la enfermedad. Asimismo, explicamos la patogenia, el pronóstico junto con las características importantes que determinan el curso clínico de IPAF, y revisamos las estrategias de tratamiento.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a manifestation of multiple rheumatic diseases, which contributes substantially to morbidity and mortality.1,2 While in many cases the underlying rheumatologic diagnosis is clear, in up to 14% of patients seen in ILD clinics, no defined rheumatic disease can be found, despite features that suggest an immune etiology.3 These patients were previously labeled as undifferentiated connective tissue disease (UCTD)-associated ILD,4 lung-dominant CTD,5 or autoimmune-featured ILD.6 As those patients often do not fit neatly within other ILD subtypes, early disease management is critically hindered. In 2015, the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and American Thoracic Society (ATS) created a task force aiming to develop a strategy that aids ILD classification for such patients. This task force coined the term interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) to describe these patients for research purposes. Domains considered in the classification criteria for IPAF include presence of interstitial pneumonia, clinical signs/symptoms suggestive of a rheumatic process, presence of specific autoantibodies, and a radiographic or histologic inflammatory pattern of lung injury.7

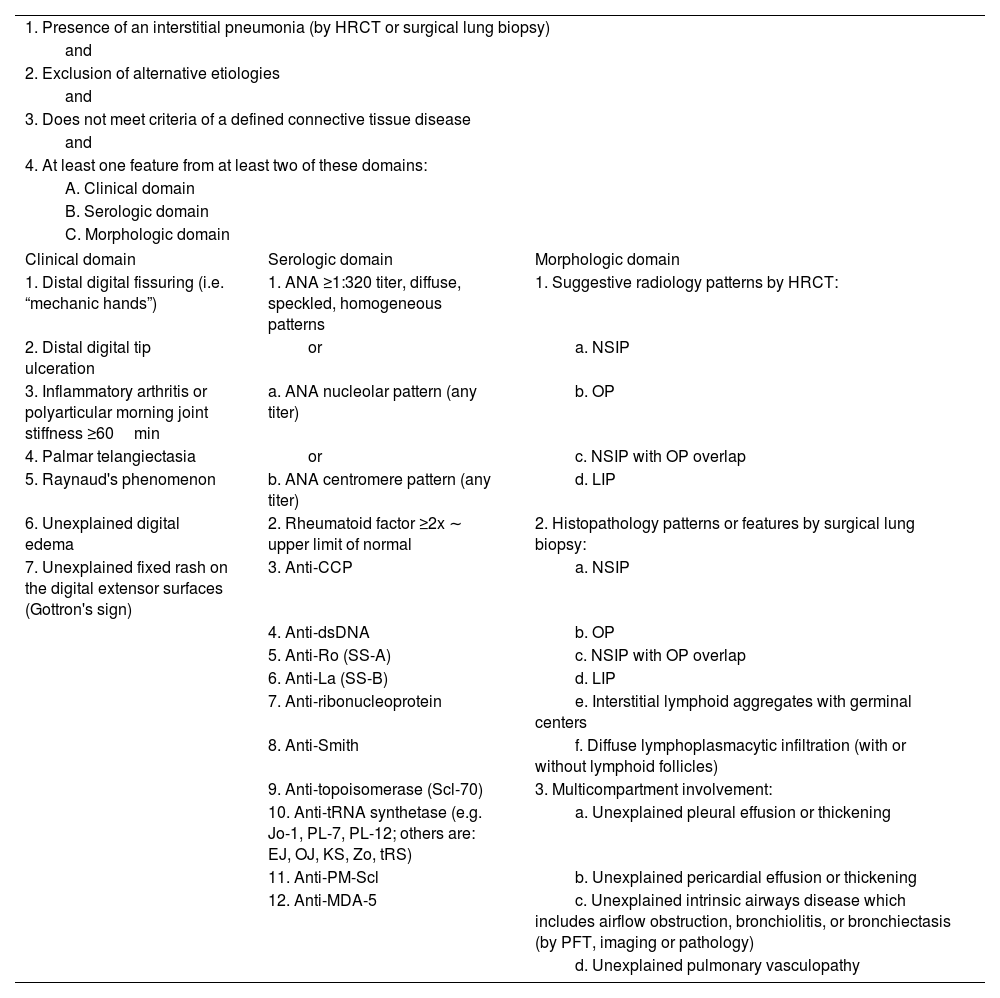

IPAF classificationIPAF classification includes the presence of interstitial pneumonia and features from at least two of three domains: clinical, serological, and morphological (Table 1).

Classification for interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features.

| 1. Presence of an interstitial pneumonia (by HRCT or surgical lung biopsy) | ||

| and | ||

| 2. Exclusion of alternative etiologies | ||

| and | ||

| 3. Does not meet criteria of a defined connective tissue disease | ||

| and | ||

| 4. At least one feature from at least two of these domains: | ||

| A. Clinical domain | ||

| B. Serologic domain | ||

| C. Morphologic domain | ||

| Clinical domain | Serologic domain | Morphologic domain |

| 1. Distal digital fissuring (i.e. “mechanic hands”) | 1. ANA ≥1:320 titer, diffuse, speckled, homogeneous patterns | 1. Suggestive radiology patterns by HRCT: |

| 2. Distal digital tip ulceration | or | a. NSIP |

| 3. Inflammatory arthritis or polyarticular morning joint stiffness ≥60min | a. ANA nucleolar pattern (any titer) | b. OP |

| 4. Palmar telangiectasia | or | c. NSIP with OP overlap |

| 5. Raynaud's phenomenon | b. ANA centromere pattern (any titer) | d. LIP |

| 6. Unexplained digital edema | 2. Rheumatoid factor ≥2x ∼ upper limit of normal | 2. Histopathology patterns or features by surgical lung biopsy: |

| 7. Unexplained fixed rash on the digital extensor surfaces (Gottron's sign) | 3. Anti-CCP | a. NSIP |

| 4. Anti-dsDNA | b. OP | |

| 5. Anti-Ro (SS-A) | c. NSIP with OP overlap | |

| 6. Anti-La (SS-B) | d. LIP | |

| 7. Anti-ribonucleoprotein | e. Interstitial lymphoid aggregates with germinal centers | |

| 8. Anti-Smith | f. Diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration (with or without lymphoid follicles) | |

| 9. Anti-topoisomerase (Scl-70) | 3. Multicompartment involvement: | |

| 10. Anti-tRNA synthetase (e.g. Jo-1, PL-7, PL-12; others are: EJ, OJ, KS, Zo, tRS) | a. Unexplained pleural effusion or thickening | |

| 11. Anti-PM-Scl | b. Unexplained pericardial effusion or thickening | |

| 12. Anti-MDA-5 | c. Unexplained intrinsic airways disease which includes airflow obstruction, bronchiolitis, or bronchiectasis (by PFT, imaging or pathology) | |

| d. Unexplained pulmonary vasculopathy | ||

HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; ANA: antinuclear antibody; NSIP: non-specific interstitial pneumonia; OP: organizing pneumonia; LIP: lymphoid interstitial pneumonia; PFT: pulmonary function testing.

Clinical domain consists of signs and features commonly seen in rheumatic diseases such as presence of inflammatory arthritis, palmar telangiectasias, and Raynaud's phenomenon, among others. Serological domain includes autoantibodies associated with autoimmune diseases such as ANA, anti-CCP, anti-synthetase antibodies, and extractable nuclear antigen antibodies, among others. The morphological domain of IPAF includes radiographic or pathologic features suggestive of inflammation (such as non-specific interstitial pneumonia [NSIP], lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia [LIP], organizing pneumonia [OP], NSIP/OP overlap, presence of diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, and/or presence of interstitial lymphoid aggregates with germinal centers). Additionally, the morphologic domain includes multicompartment involvement which may emerge on imaging or biopsy. It includes pleural or pericardial thickening or effusion, air trapping, and/or pulmonary vasculopathy. To be included in the domain, these findings must be unexplained, which introduces substantial heterogeneity in IPAF cohorts due to subjectivity of interpretation. Notably, the morphologic domain criteria do not include usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) as an inclusion criterion despite its frequent presence in rheumatic diseases associated ILDs (particularly rheumatoid arthritis [RA]-ILD), as in isolation, UIP is not considered suggestive of underlying inflammatory lung damage,7 though many of these patients may have ACPA+.8

IPAF epidemiologyTrue prevalence of IPAF is unknown, particularly since evaluation strategies of patients may not include complete assessment of all IPAF classifications domains. In various described cohorts, IPAF represented 5–14% of patients with ILD.3,9–11 In Latin America, IPAF represented 9.5% of patients diagnosed with autoimmune ILD (rheumatic disease associated ILD, IPAF, and ILD associated with ANCA antibodies).12

IPAF mostly affects middle- to older-aged women.3,13 In the described cohorts, majority of patients were White,3,14,15 although some cohorts included up to 48% Black people.13 Hispanics are usually not well represented in United States-based IPAF cohorts but can comprise up to 18% of patients.14

IPAF presentationSymptoms of IPAF are similar to those of other forms of interstitial lung disease with cough and dyspnea being the most common.16 IPAF, importantly, differs from many idiopathic pneumonias by having frequent autoimmune manifestations. Inflammatory arthritis and/or at least one hour of morning stiffness, as well as Raynaud's phenomenon are two of the criteria that are most reported in IPAF cohorts.3,13,17–19 Fever, rash, and sicca symptoms are common non-criteria extrapulmonary symptoms.16,17,19 On exam, crackles are a common finding.16 While each clinician should evaluate each potential IPAF patient with utmost attention to subtle autoimmune manifestations, digital tip ulcerations and Gottron sign are uncommon in IPAF, likely due to high specificity for defined rheumatic diseases such as systemic sclerosis (SSc) and idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM), respectively.14,20,21 Importantly, a clinician should evaluate for non-ILD thoracic manifestations such as pleurisy, pericardial rub and loud P2, as those might indicate multicompartment features included in the morphological domain (pleural or pericardial inflammation or fluid and the presence of pulmonary hypertension). ANA and SS-A positivity are consistently the most common autoantibodies observed in IPAF.10,13,17,22 In terms of radiographic features, NSIP is the most common pattern observed on HRCT of chest, although any other pattern can be seen.3,23

IPAF prognosisRisk of progression to rheumatic diseasesAlevizos et al., evaluated 174 patients with ILD which included 50 patients with IPAF and found that 14% of patients with IPAF progressed to rheumatic disease over a median of 3.4 years. Rheumatic diseases represented included RA, SSc, IIM, and ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV), leading the authors to suggest that ANCA should be included in serologic domain.9 There is a possibility that more of the patients with IPAF are at risk of progression to rheumatic disease, but this could be masked by immunomodulating medications that these patients are often on. This is supported by a cohort from Colorado described by Chartrand et al., where none of the 56 patients with IPAF followed for four years progressed to a defined rheumatic disease and 55 of them were on immunosuppressive medication, similar to the Alevizos study where 48 (96%) of patients were on immunosuppressive therapy.9,22 However, it is possible that various features of IPAF confer differential risk for progression to rheumatic disease. For example, among 146 patients with IPAF positive for anti-synthetase antibodies (55% patients were positive for Jo-1), 42% of patients progressed to IIM or IIM/RA overlap over a median of 12 months.24 Decker et al., found that 26% of patients with IPAF progressed during follow-up after a mean of 25 months – nine to anti-synthetase syndrome, eight to SSc, and one overlap myositis with non-statistically significant risk factors for progression being presence of anti-synthetase antibodies, younger age, female sex, puffy fingers, and abnormal nailfold capillaroscopy.20 It is possible that IPAF with myositis-specific antibodies (MSA) such as anti-synthetase antibodies, MDA5, anti-signal recognition particle antibody, among others, may represent a spectrum of IIM-ILD given high risk of progression to clinical myositis in IPAF-MSA and an observation of similar clinical behavior in terms of survival and response to immunosuppression in IPAF-MSA and IIM-ILD.25

Part of the challenge with classifying IPAF and with its progression to rheumatic disease is varying and subjective application of classification criteria and evaluation of patients by clinicians. A study by Auteri et al., found that undiagnosed Sjogren disease (SjD) is prevalent among patients with IPAF (45.5% of the prospective cohort of 44 patients with IPAF). Primary SjD was classified more frequently using minor salivary lip biopsy, Schirmer test, ocular staining score, and antibody testing in those who has ANA 1:320 or higher, positive SS-A, and complained of xerophthalmia.26 This highlights the need for uniform testing and careful rheumatologic evaluation of all patients with ILD and autoimmune features.

Lung function decline and survivalIn terms of lung disease progression and survival in IPAF, several features have been identified as being poor prognostic factors. Despite UIP not being considered in the morphologic domain, UIP has been consistently identified as a risk factor for reduced survival in multiple cohorts,3,27,28 although this was not corroborated in other studies.13,29 Oldham et al., found that IPAF-UIP has survival similar to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a serious and prototypical fibrotic ILD with relentless progression and poor survival. IPAF-non-UIP has survival that approximates that of patients with rheumatic disease associated ILD in Chicago cohort of patients with ILD followed for 100 months.3 Kelly and Moua evaluated a cohort of patients with IPAF and IPF followed until death for up to 150 months. While the groups were otherwise demographically and functionally similar, they found that survival in IPAF-UIP was significantly worse than in IPAF-non-UIP but not significantly different from survival in IPF.15 Based on these findings, some authors suggested that UIP may need to be an exclusion criterion for classification of IPAF due to concern that inclusion of patients with UIP inadvertently includes patients with non-autoimmune driven IPF who happen to have some positive serologies and other non-specific features which allow them to classify as IPAF.15,30 However, this conclusion may not be uniformly appropriate as highlighted in the study by Graham et al., where IPAF-MSA had excellent prognosis and response to treatment despite 12% of patients having UIP pattern.25 Additionally, in a study by Huapaya et al., there was no difference in survival based on UIP or non-UIP pattern, with 80% of patients having clinical domain features in addition to the serological domain,13 indirectly suggesting a larger burden of autoimmunity. Thus, not all patients with IPAF-UIP may behave the same, and further studies investigating prognostic markers in IPAF should enroll patients with UIP to investigate whether presence of UIP pattern affects survival in various IPAF phenotypes.

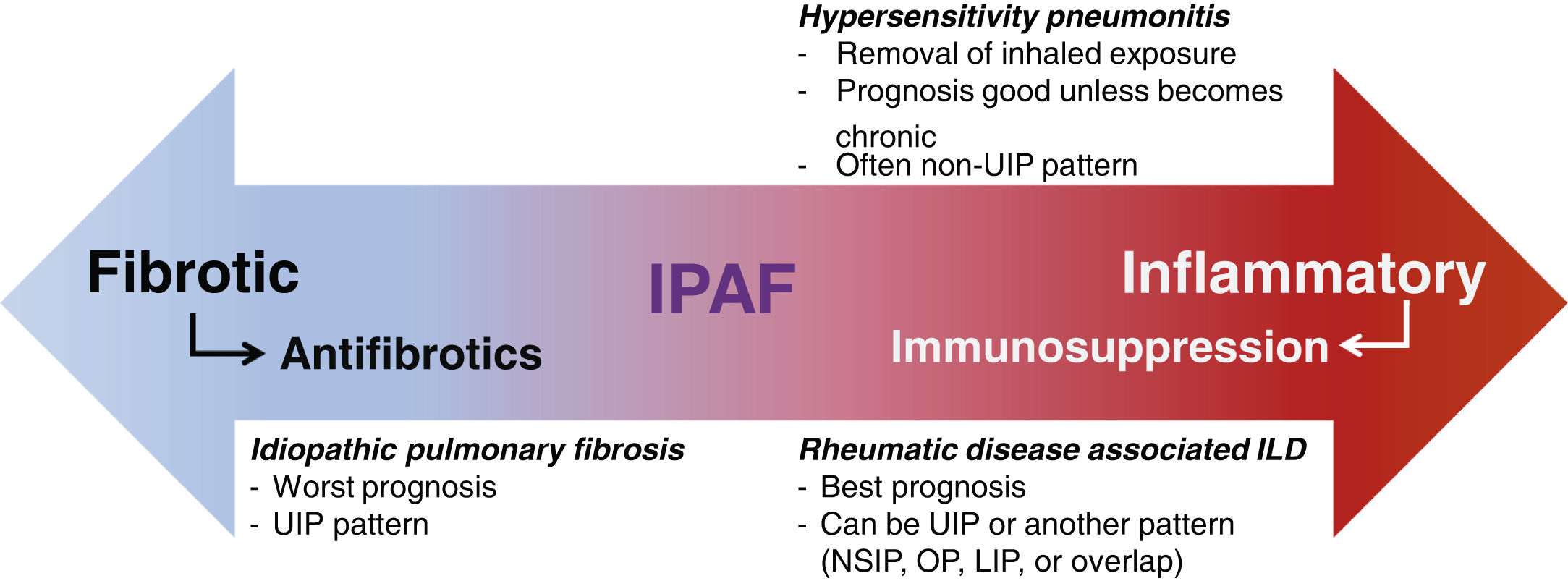

IPAF pathogenesisClassification of IPAF presumes autoimmune etiology, though its inherent heterogeneity may make it difficult to identify specific etiologic factors. Mechanisms similar to those in rheumatic disease associated ILD are assumed to drive the pathogenesis in IPAF. However, as survival in IPAF cohorts tends to be worse than in rheumatic disease associated ILD,3 the notion that the pathogenesis is the same may not be uniformly true. It is possible that IPAF may have pathogenesis that is different from both rheumatic disease associated ILD and IPF or it may represent a heterogeneous group with variable pathogenesis, with some patients representing rheumatic disease associated ILD-like phenotype and some representing IPF-like phenotype (Fig. 1).

IPAF has unclear pathogenesis, prognosis, and optimal management. IPAF: idiopathic pneumonia with autoimmune features; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; ILD: interstitial lung disease; NSIP: non-specific interstitial pneumonia; OP: organizing pneumonia; LIP: lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia.

A study comparing 32 patients with IPAF and 20 healthy controls found significantly reduced levels of galectin-9 in plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of patients with IPAF. Additionally, lower galectin-9 levels correlated with impaired humoral immunity, higher levels of autoantibodies, and worse lung function.31 Interestingly, galectin-9 has been, in contrast, found to be elevated in MDA5 dermatomyositis-associated ILD, IPF, and other types of ILD (including chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis [cHP] and idiopathic NSIP),32,33 emphasizing the need to continue investigations of its role in pathogenesis.

Liang et al., suggested that C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)-1-C-X-C motif receptor (CXCR)-2 axis may be involved in the pathogenesis of IPAF lung disease progression due to finding that IPAF exhibits higher plasma levels of CXCL-1 than other lung diseases, which included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs), and that high CXCL-1 plasma levels clinically correlated with ongoing acute exacerbation, parenchymal involvement, diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) in IPAF. Additionally, BAL fluid CXCL-1 level correlated with BAL fluid neutrophil count, and CXCR-2 was found within inflammatory aggregate in IPAF lungs. Furthermore, IPAF exhibited higher cytokine level profile than IIPs, with interleukin (IL)-4, IL-6, IL-13, and IL-17 being significantly elevated.34

Ramos-Martinez et al., performed several studies on the pathogenesis of ILD associated with anti-aminoacyl transfer-RNA-synthetase autoantibodies which included IIM-ILD and IPAF and found that those patients who progressed were characterized by higher levels of T-helper cell (TH)-17 related cytokines and/or soluble CD163 at baseline.35,36 However, these findings are difficult to extrapolate to other patients with IPAF since, as discussed, IPAF-MSA may represent a spectrum of myositis-ILD.25

Genetic studies have also been done in IPAF. Newton et al., evaluated peripheral leukocyte telomere length (LTL), frequency of MUC5B and TOLLIP alleles (common in IPF), and their effect on survival in IPAF. They found that compared to IPF, age-adjusted LTL was longer for IPAF and rheumatic disease associated ILD. However, LTL was shorter in IPAF-UIP than in IPAF-non-UIP. Additionally, LTL less than 10% expected was associated with faster lung decline and worse transplant-free survival in IPAF. As for allelic frequency, MUC5B promoter variant frequency was higher in IPAF than in rheumatic disease associated ILD (yet still lower in IPF) and was associated with worse transplant-free survival in IPAF, opposite to its effect in IPF. The frequency of TOLLIP allele was lower in IPAF than in IPF and similar to frequency of rheumatic disease associated ILD and had no effect on survival in any of the ILD types in the study.37 This study highlights the possible differential effect of genetic markers and telomere length on clinical course and survival in IPAF and other types of ILD.

Prior attempts have been made to separate IPAF into subtypes based on predominant clinical and serological features, with 60% of patients with IPAF classified into a defined rheumatic disease-like subgroup.13 However, no difference in survival was observed between the groups. Such comparisons are limited by the lack of consensus in separating IPAF into subtypes. Further studies need to be done to evaluate whether treatment strategies should differ among such IPAF subgroups.

Kameda et al., attempted to discriminate between types of ILD using serum biomarkers and found that CXCL-9, CXCL-10, and CXCL-11 had good discriminatory capacity between rheumatic disease associated ILD and IPF but poor to fair capacity for discrimination between IPF and IPAF and rheumatic disease associated ILD and IPAF, respectively. This again supports the notion that IPAF is a heterogeneous entity comprised of patients phenotypically similar to rheumatic disease associated ILD or IPF.38 To investigate this question, Rzepka-Wrona et al., performed a pilot study to differentiate inflammatory and fibrotic pathways between IPAF, rheumatic disease associated ILD, and IIP and found that nine patients with IPAF had significantly lower IL-8 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-b1 in BAL than the 15 patients with rheumatic disease associated ILD but similar to the levels in 16 patients with IIP. Furthermore, BAL fluid IL-8 level predicted total cell count in BAL fluid in IPAF. The IIP group was not clearly defined, although 62.5% of them had UIP pattern, suggesting predominantly fibrotic IIP type.21 This study highlights an important approach to characterizing IPAF by direct comparison of patient characteristics with other ILD subtypes to best assign the underlying pathogenesis of patients. Further studies directly comparing pathogenesis in rheumatic disease associated ILD, IPAF, and IPF can help clarify phenotypes and endotypes in IPAF.

IPAF managementConsensus regarding IPAF management has not been reached, in part due to unclear pathogenesis and heterogeneity of clinical course. Therefore, multifaceted pragmatic approach is likely most appropriate. The timing of start of therapy is often not clear in IPAF, with some clinicians electing to wait for the patient to develop progressive lung function decline before initiating treatment, and some electing to initiate therapy in a patient with diminished lung function parameters.

Since clinical features of patients with IPAF often overlap with those in patients with rheumatic disease associated ILD, IPAF is assumed to have autoimmune etiology and is often treated with immunosuppressive agents, However, studies confirming the inflammatory etiology and efficacy of specific therapies are lacking. At this point, it is unclear which features are important for choice of therapy, but generally those patients with predominantly fibrotic pattern on imaging are frequently initiated on antifibrotic therapy, while those with multiple autoimmune features and more inflammatory features such as ground-glass opacities (GGOs),39,40 are started on immunosuppression first. The role of combination therapy is also not straightforward, as trials directly investigating this have not yet been done.

Immunosuppressive agentsA variety of immunomodulating medications have been tried in IPAF. Glucocorticoids are used to gain quick control of disease activity.41 Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is frequently the first line steroid-sparing medication, a strategy extrapolated from Scleroderma Lung Study II trial.42 Azathioprine and cyclophosphamide use have also been extrapolated from studies in rheumatic disease associated ILD.43,44 JAK inhibitors demonstrated effectiveness particularly in IPAF-MSA.45 In a retrospective study of rituximab in patients with IPAF at two centers, patients with IPAF receiving this treatment have shown improvement.46 Given demonstrated effectiveness in other types of ILD, a variety of other medications such as tocilizumab, intravenous immunoglobulin, tacrolimus, and abatacept have also been used.47–50

A concern for the use of immunosuppressive medications in IPAF-UIP has emerged after reports that patients with IPAF who have UIP pattern may have worse outcomes, similar to IPF.3,15 Treatment with N-acetylcysteine, azathioprine, and prednisone in combination resulted in increased mortality in patients with IPF compared to placebo in the landmark PANTHER-IPF study.51 A post hoc analysis showed that treatment with MMF also increased mortality in patients with IPF.52 Therefore, immunosuppression is often avoided in IPAF-UIP. It needs to be noted that rheumatic disease associated ILD with UIP pattern is still often treated with immunosuppression with no increase in mortality.53 In the INBUILD trial, baseline immunosuppression treatment was not associated with worse outcomes among those with rheumatic disease associated ILD, many of which had UIP pattern, although the trial was not powered to detect outcomes in this group.54 Additionally, a prospective study of 79 patients with IPAF demonstrated improved survival with glucocorticoid therapy in IPAF-UIP in multivariate analysis.55 Therefore, more studies are needed to evaluate whether avoiding immunosuppressive therapy in IPAF, or subtypes based on UIP, is an optimal strategy.

Antifibrotic therapyA retrospective study of 184 patients found that pirfenidone treatment helps improve FVC decline in IPAF after 3, 12, and 24 months and lowers corticosteroid requirement after 12 months of treatment.56 Additionally, two randomized controlled trials have suggested that antifibrotics can be beneficial in IPAF. Flaherty, et al., investigated nintedanib in progressive fibrosing ILD (INBUILD trial) which was comprised of 663 patients followed over 24 weeks. Of the patients, 26% had autoimmune ILD and 21% had unclassifiable ILD. Patients with IPAF were included in the trial, although their number was not explicitly stated.57 The nintedanib group had less FVC decline than 331 patients in the placebo group (81ml versus 188ml).58 A post hoc analysis of the trial over 52 weeks investigated the effect of combined immunomodulatory therapy with nintedanib. Even though the rate of decline in FVC was numerically greater in subjects in the placebo group who were taking glucocorticoids at baseline than in those who were not, the study was not designed to evaluate whether immunosuppressive treatments are beneficial or not in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis of different causes. Thus, in this subanalysis it was observed that the effectiveness of nintedanib to reduce the rate of decline in FVC is not influenced by the use of immunomodulatory therapies and that it may be used in combination.59 Another trial by Maher et al., investigated pirfenidone (n=127) versus placebo (n=126) over 24 weeks in unclassifiable ILD. Thirteen percent of patients met IPAF classification criteria. Pirfenidone reduced FVC decline as compared to placebo (88ml versus 157ml).60 Importantly, 30% of patients were concomitantly treated with MMF. Interestingly, a subgroup analysis of patients treated with MMF suggested that pirfenidone was less effective in those patients with unclassifiable ILD who were receiving concomitant MMF, although the analysis was limited by sample size and study design, which was not intended to detect differences between subgroups.61 Further trials of combination therapy with antifibrotics and immunomodulating agents which are powered to detect effect on clinical outcome in various ILD subtypes are needed.

Multidisciplinary approach to the management of a patient with IPAF is crucial. Multiple comorbidities are common in IPAF, particularly hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.3,17,62 Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is common in IPAF. In a cohort of 47 patients with IPAF, 12.7% of patients were found to have PH with only a third of the cohort having had right heart catheterization performed.10 The high prevalence of PH suggests the need for systematic PH screening in patients with IPAF. Although it is yet unclear how much aggressive management improves outcomes in this population, screening for the most common comorbidities should be performed. Additionally, frailty leads to worse outcomes in a variety of ILDs63 and thus physical and pulmonary rehabilitation should be part of the management tools.

ConclusionConflicting conclusions and underlying heterogeneous pathobiology offer us limited glimpses on IPAF pathogenesis and ways to delineate pathways responsible for IPAF occurrence and pulmonary damage. IPAF is a heterogeneous lung disease, some of which may be similar to rheumatic disease associated ILD, some which may be a precursor to rheumatic disease associated ILD, some which may be more similar to another type of ILD such as IPF, and some, quite possibly, representing a unique entity. Efforts should focus on identifying common and divergent pathways of fibrosis and inflammation in ILD. Importantly, IPAF offers us an opportunity to explore yet undifferentiated autoimmune disease limited to the lung. Patients suspected of having IPAF should undergo multidisciplinary evaluation and the use of complementary methods such as salivary gland biopsy or ultrasound to evaluate for underlying SjD,64 capillaroscopy to detect subtle nailfold capillary changes,65 power doppler ultrasound to assess for joint inflammation66 which would improve patient diagnosis and remove some of the heterogeneity introduced by patient misclassification in IPAF cohorts. We need to focus on optimal separation of these patients and refining of the criteria using serum and lung biomarkers, transcriptomic analyses, and longitudinal studies of patients with IPAF. Ultimately, the molecular profiles should be linked with the clinical profiles and trajectories of IPAF patients to define specific endo-phenotypes. These studies would also help refine the criteria further. It is conceivable that comparison of various IPAF subtypes with specific types of rheumatic disease associated ILDs may identify patients who should be considered a spectrum of certain rheumatic disease associated ILDs based on disease trajectory and biomarkers, similar to IPAF-MSA moving to be considered a spectrum of IIM-ILD. Perhaps this would allow some rheumatic disease classification criteria to expand to include ILD for disease classification. Ideally, this approach would also identify those patients with IPAF who should be considered to have IPF (i.e., those without any objective evidence of an inflammatory process). It is possible that the refined criteria would include only a portion of patients previously classified as IPAF, those who are not on a spectrum of any defined rheumatic disease associated ILD but yet have a detectable autoimmune process. We suggest that patients with this form of lung disease be referred to as having Autoimmune-mediated ILD (AIM-ILD). In summary, given the therapeutic implications, it is imperative that the underlying mechanistic features be further explored to improve categorization and inform targeted management strategies.

Conflict of interestThe authors report no relevant conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.