Gastrointestinal involvement in SLE has been reported in up to 50%, generally secondary to the adverse effects of treatment. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction is caused by hypomotility related to ineffective propulsion. The case of a 51-year-old patient with intestinal obstruction is presented. She was taken to surgical management due to suspicion of adhesions, with a stationary clinical course; the control tomography documented loop dilation and bilateral hydroureteronephrosis, associated with markers of lupus activity. It was managed as an intestinal pseudo-obstruction due to SLE with resolution of her symptoms. High diagnostic suspicion results in timely treatment and the reduction of complications.

El compromiso gastrointestinal en lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) ha sido reportado hasta en un 50%, generalmente secundario a los efectos adversos del tratamiento. La pseudoobstrucción intestinal es causada por hipomotilidad relacionada con una propulsión inefectiva. Se presenta el caso de una paciente de 51 años, con obstrucción intestinal por sospecha de bridas, que fue llevada a manejo quirúrgico y tuvo una evolución clínica estacionaria. La tomografía de control documentó dilatación de asas e hidroureteronefrosis bilateral, en tanto que los paraclínicos mostraron actividad lúpica. Se manejó como una pseudoobstrucción intestinal por LES con resolución del cuadro. La alta sospecha diagnóstica favorece el tratamiento oportuno y la disminución de las complicaciones.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease of the connective tissue that presents a wide range of systemic manifestations, including gastrointestinal; it is observed in up to 50% of cases1,2; mostly attributed to adverse drug effects3,4. Those related to the disease are less frequent, including intestinal pseudo-obstruction, a disorder frequently associated with changes in the urinary tract1,5,6. A case of a patient with long-standing SLE who consulted for postprandial vomiting and abdominal distension of several months of evolution is described. Initially, it was managed as intestinal obstruction due to flanges, and later, intestinal pseudo-obstruction due to lupus was diagnosed.

Case reportA 51-year-old female patient with a diagnosis of SLE since the age of 17, with cutaneous and pleuropericardial involvement (pericarditis and recurrent pleuritis that required pleurodesis), who was treated with prednisolone 5 mg/day, without rheumatology follow-up. The patient consulted due to symptoms lasting eight months, with weight loss of approximately 30 kg, chronic diarrhea that was neither dysenteric nor lienteric, abdominal distension, postprandial vomiting, asthenia, and adynamia. In the 15 days before the consultation, she presented an increase in bloating, nausea, and vomiting 30 min after meals, as well as generalized abdominal pain. The surgery group treated it as an intestinal obstruction since her abdominal contrast tomography showed dilation of all the loops of the small intestine, with no signs of distress up to the terminal ileum, which collapsed together with the cecum.

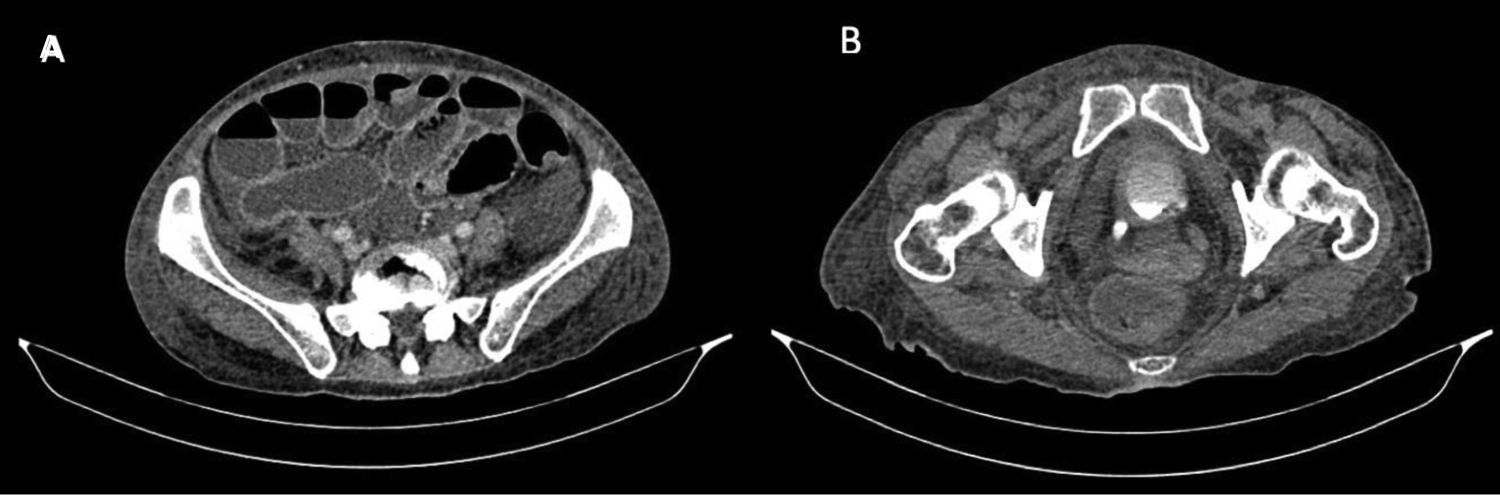

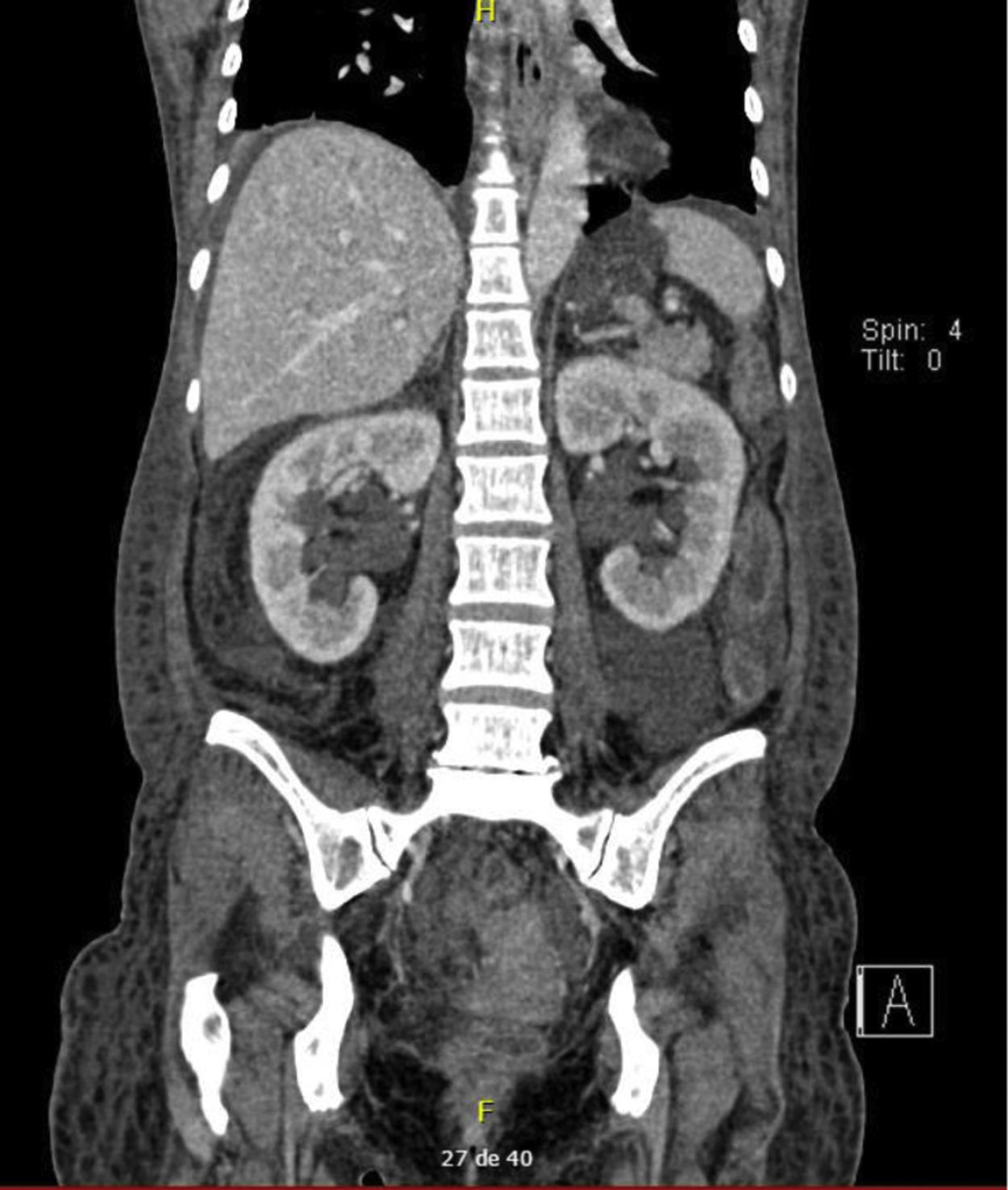

The diagnosis of congenital bands was raised since the patient had no history of abdominal surgery or intestinal stenosis due to vasculitis. In the exploratory laparotomy, multiple flanges were documented that were released; however, there was no favorable clinical response. The control abdominal contrasted CT, requested with the phase of contrast excretion for an adequate evaluation of the urinary tract, showed persistent dilation of intestinal loops and bilateral hydroureteronephrosis associated with inflammatory changes of the bladder (Figs. 1 and 2), for which intestinal pseudo-obstruction due to SLE was suspected.

Laboratory studies were compatible with lupus activity: hypocomplementemia, lymphopenia, and positive anti-dsDNA, without renal involvement (Table 1). Additionally, on admission, hypokalemia developed, but during hospitalization, potassium replacement was instituted, and on the fifth day normal values were achieved, although the symptoms persisted (Table 2). Immunosuppression was started with pulses of methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2, after which the patient presented improvement in her symptoms, with the disappearance of vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal distension. The flanges described in the surgical procedure, although there was no reported background, were probably secondary to episodes of subclinical serositis.

Initial paraclinical and immunological profile.

| Paraclinical | Value | Reference value |

|---|---|---|

| ALT | 14 U/L | 0−55 |

| AST | 20 U/L | 5−34 |

| Total bilirubin | 0.24 mg/dL | 0.2−1.2 |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.06 mg/dL | 0.1−0.5 |

| Calcium | 7.4 mg/dL | 8.4−10.2 |

| Sodium | 131 mmol/L | 136−145 |

| Potassium | 2.94 mmol/L | 3.5−5.1 |

| Magnesium | 1.66 mg/dL | 1.6−2.6 |

| Albumin | 2 g/dL | 3.5−5 |

| Creatinine | 0.57 mg/dL | 0.6−1.1 |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 15.5 mg/dL | 9.8−20.1 |

| C-reactive protein | 3.01 mg/dL | 0.01−0.82 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 3.01 mm/h | 0−20 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.3 g/dL | 12−15 |

| Medium corpuscular volume | 77 fL | 80−98 |

| Leukocytes | 3700 mm3 | 4500−11,000 |

| Neutrophils | 2500 mm3 | 1500−6600 |

| Lymphocytes | 600 mm3 | 1500−3500 |

| Platelets | 239,000 mm3 | 150,000−450,000 |

| C3 | 52 mg/dL | 83−193 |

| C4 | 9 mg/dL | 15−45 |

| 24-hour proteinuria | 0.7 g/24 h | |

| Immunologic profile | ||

| Anti-DNA | 1:320 | |

| Anti-RNP | 155 - Positive | <15 |

| Anti-Sm | 26.5 - Positive | <15 |

| Anti-Roo | 5.2 - Negative | <15 |

| Anti-La | 2.7 - Negative | <15 |

A case of intestinal pseudo-obstruction due to SLE is presented in a patient with diarrhea, abdominal distension, weight loss, and intractable vomiting. Gastrointestinal manifestations can be as common as 50% of patients1,2, mostly related to adverse drug effects or infectious complications associated with immunosuppression, but more cases linked to the baseline disease have been described4.

Gastrointestinal tract involvement in SLE is variable and can impact the mouth to the rectum, with mucosal affection being more frequent, especially oral2. Following these, the manifestations most described in the literature are protein-losing enteropathy, liver involvement, pancreatitis, and intestinal pseudo-obstruction (Table 3)2,7.

Intestinal pseudo-obstruction is defined as a process of intestinal hypomotility related to ineffective propulsion, which produces the classic symptoms of intestinal obstruction, but without an anatomical cause1,8. The symptoms of this condition are usually postprandial, start acutely, and are a reason for early emergency consultation; however, their duration from three days to three years has been reported, with the possibility of chronic intestinal obstruction, malnutrition, and weight loss1,6,7.

In the largest systematic review carried out to date, published in 2017, which included 150 patients with intestinal obstruction, the most frequent symptoms were reported as abdominal pain (85%), nausea and vomiting (82%), being less frequent abdominal distension (62%), diarrhea, and constipation7. Other case reports report similar frequencies of symptoms, with abdominal pain always being more prevalent9.

In addition to the symptoms related to intestinal pseudo-obstruction, visceral muscular dysmotility syndrome is described, which occurs in 3/4 of the patients, in which hydroureteronephrosis and dilation of the biliary tract are observed, which produces symptoms related to interstitial cystitis1,4,6,7.

The pathogenesis of intestinal pseudo-obstruction is still not fully clarified. Processes related to the involvement of visceral smooth muscle, enteric nerves, the autonomic nervous system, and vasculitis of the intestinal wall have been described2,4,6,10. Histopathological studies have found repeatedly affection of the small intestine, such as involvement mainly of the muscular layer, with the presence of edema and intestinal inflammation, infiltration of inflammatory cells (predominantly eosinophils), myocyte necrosis related to the underlying inflammation, atrophy, and fibrosis4,11,12. These findings suggest that the pathophysiological process could have the myocyte as its primary target, rather than being related to vasculitis due to SLE11,13.

The diagnosis of intestinal pseudo-obstruction is based on the symptoms and the background, since it generally occurs in patients with a previous diagnosis of SLE, although less frequently it can appear at disease onset2. Lupus activity should always be evaluated; the most common association is hematological involvement, which occurs in 75% of the cases7.

An abdominal x-ray in a standing position is usually the first diagnostic aid in which the classic signs of intestinal obstruction are evident, such as dilated loops and air-fluid levels6,12. Contrast-enhanced abdominal tomography makes it possible to define the absence of an anatomical cause related to the symptoms and confirms the presence of dilated loops, thickening of the wall, and if present, hydroureteronephrosis and dilated biliary tract6. The requested paraclinical tests should be the same used as the approach to patients with lupus, searching for activity and organ involvement, since no antibody specifically associated with intestinal pseudo-obstruction has been found, although a high prevalence of antiRo/SSA has been observed, and, in some reports, antiLa/SSB7,10,12,14. In this patient, these antibodies were negative.

Treatment in these patients has been based on support measures and immunosuppression. On the one hand, symptomatic management includes prokinetics, abdominal decompression with a nasogastric tube, and total parenteral nutrition (if necessary), especially in subjects with chronic obstruction4,6,7. In some cases, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy has been considered as part of management, to avoid the risk of bacterial overgrowth4,6. Regarding immunosuppressive management, the most used and has been shown to achieve remission in isolated cases, are methylprednisolone pulses followed by oral prednisolone, associated with cyclophosphamide; some response has also been demonstrated with azathioprine, cyclosporine A, and tacrolimus2,4,7,9.

The prognosis is generally favorable, with response rates of up to 93%, sustained remission of up to 76%7, and greater relapse in patients who were initially surgically treated or with a delay in diagnosis9,14. Mortality ranges from 6.99% to 18%, especially due to infections, cerebral or meningeal hemorrhage, or lupus involvement of other organs1,4,7.

In conclusion, we present the case of a patient who presented with abdominal distension, persistent vomiting, diarrhea, and weight loss, who was diagnosed with intestinal pseudo-obstruction secondary to baseline SLE, and who had a favorable response to immunosuppressive and supportive treatment. This disorder, which is rare and of which few cases have been published, is important to recognize for the administration of adequate and prompt treatment.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe authors declare that no experiments on humans or animals have been performed for this research. They also state that no patient data appear in this article and that all patients signed the habeas data on admission to the hospital.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.