Schnitzler syndrome is a rare disease, in Colombia it is considered an orphan disease, of an auto-inflammatory nature, classified as a complex acquired inflammatory type of disease, which classically produces urticarial rash, long-standing fever, adenomegalies, and arthralgias coexisting with monoclonal gamma peak typically of the IgM type. We present the case of a young woman, with a larval picture that started with urticarial rash, with clinical characteristics compatible with the syndrome and evidence of monoclonal peak in protein electrophoresis meeting Lipsker-Baltimore 2001 criteria and Strasbourg 2013 criteria for diagnosis.

El síndrome de Schnitzler es una enfermedad rara, en Colombia se la considera dentro de las enfermedades huérfanas, de carácter autoinflamatorio y se la clasifica como tipo inflamosopatía adquirida compleja que produce clásicamente la presencia de rash urticarial, fiebre de larga data, adenomegalias y artralgias que coexisten con pico gamma monoclonal típicamente de tipo IgM. Se presenta el caso de una mujer joven, con cuadro larvado que inició con rash urticarial y características clínicas compatibles con el síndrome y evidencia de pico monoclonal en electroforesis de proteínas que cumple con los criterios de Lipsker-Baltimore 2001, así como con los criterios de Estrasburgo 2013 para el diagnóstico, y mejoría clínica tras la instauración de tratamiento inmunomodulador.

Schnitzler syndrome is a rare, chronic disorder categorized as autoinflammatory and classified within this spectrum as complex acquired inflammopathy.1–3 The first case was described in 19721,4,5 and, despite its distant description in the literature, there are still no more than 300 case reports, and it remains an unknown disorder in everyday medical practice.5 This disorder affects males with a slight predominance, with an average onset age of 40–50 years; yet great heterogeneity has been evidenced through case reports of subjects from adolescents to octogenarians.1,5,6 It is clinically characterized by the appearance of a recurrent non-pruritic urticarial rash, associated with a monoclonal gamma peak that may in turn be associated with chronic fever, lymphadenopathy, hepato or splenomegaly, and arthralgias with the presence of bone pain.6,7

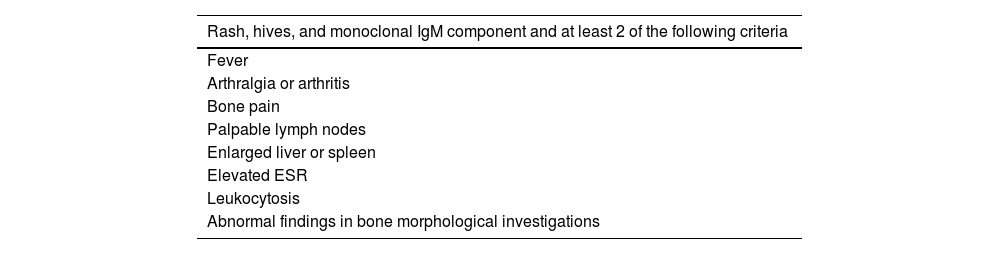

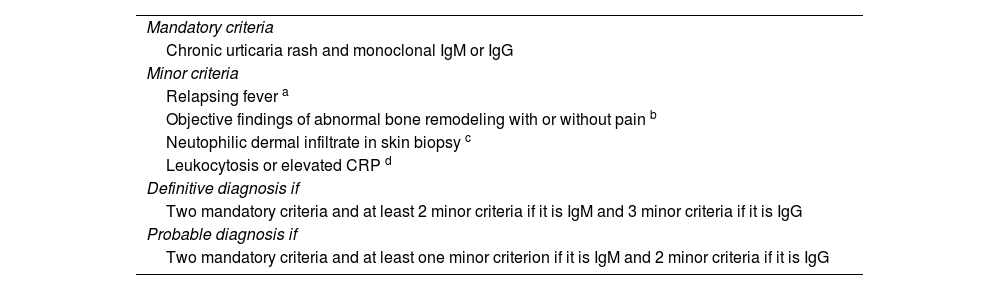

In 2001, the Lipsker-Baltimore diagnostic criteria were established, which were replaced in 2013 by the Strasbourg criteria. The latter have proven to be more practical in the clinical setting, since they only require the coexistence of 2 major criteria (chronic urticarial rash and IgM or IgG monoclonal gammopathy) and at least 2 minor criteria (intermittent fever, arthralgia or arthritis, bone pain, palpable lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly or hepatomegaly, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, leukocytosis, and bone abnormalities).5

The pathophysiology has not been fully understood and attempts have been made to compare it with other autoinflammatory syndromes, including the cryopiridine-associated periodic syndrome, to elucidate the physiopathogenic mechanism, which is compatible with the dysregulation of innate immunity mediated by neutrophils and monocytes.3,9,11,13

It has not been possible to determine a genetic basis that explains the etiology of the disease, but it is known that patients present a high secretion of cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6 by monoclonal cells, which constitutes a severity marker.5

In this sense, the elevation of cytokines has been correlated with the clinical manifestations of the disease, attributing its specific effects in different organs, in such a way that IL-1β represents a signaling molecule that induces an increase in endogenous pyrogens in the central nervous system (specifically at the hypothalamus), with the subsequent elevation in body temperature and the fever characteristic of the syndrome.9

The increased production of IL-1β by skin mast cells explains the presence of chronic urticaria in these individuals. The role of IgM monoclonal gammopathy has not yet been elucidated, as there is controversy over whether this finding is a cause or a consequence of the disorder. The most accurate hypothesis points to persistent stimulation of the IL-1 receptor, which could lead to monoclonal production of IgM.1

From this perspective, IL-1ß has been established as a pharmacological target, and good results have been obtained using the inhibitor anakinra, with remission levels of up to 83%.1,9,11 Canakinumab has also demonstrated adequate effectiveness in these subjects.1 The use of other therapeutic measures such as corticosteroids, interferon alpha, and colchicine has moderate effectiveness and a high risk of adverse reactions; therefore, they have not been universally recommended.1

The case of a young patient with chronic urticaria and subsequent clinical manifestations is presented, which, with the support of extension studies, led to the diagnosis of Schnitzler syndrome, a rare disease of which there is no documentation of local or national cases. Hence, it constitutes the first case report of a patient in which the diagnosis of Schnitzler syndrome is confirmed in Colombia based on the Strasbourg criteria.

As previously stated, knowledge of this disorder is relevant to broaden the diagnostic horizon and establish this nosological entity within the differential spectrum of the patient with a confluence of fever of unknown origin and skin lesions, specifically of the chronic urticarial type. Based on this, we aim to optimize the knowledge of an underestimated disease to make an earlier diagnosis, which allows establishing a timely treatment that avoids exposure to unnecessary medications and optimizes early therapy, so that it leads to a better outcome and prognosis, and to reduce morbidity and mortality.

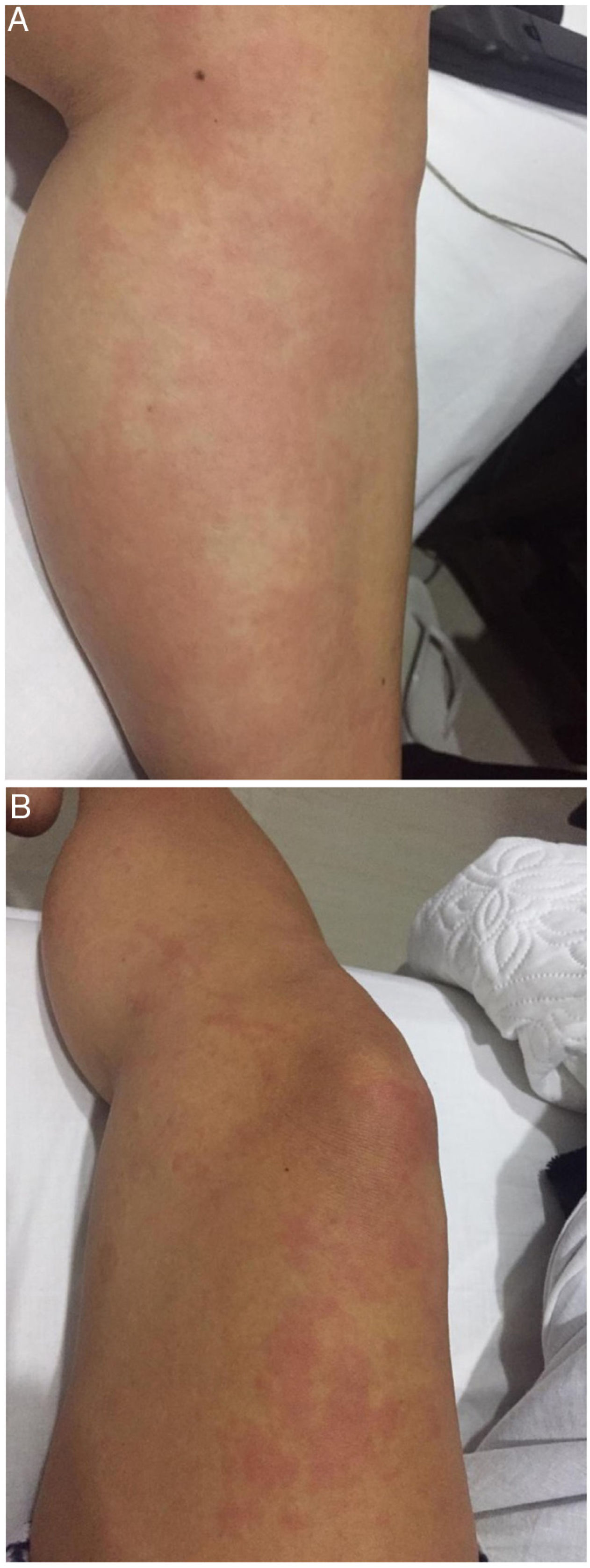

Case presentationA 26-year-old, mestizo female patient with a history of autoimmune thyroiditis who has been followed up by endocrinology for 6 years, presented with clinical symptoms of four months of evolution that began with urticarial rash in the lower limbs (Figs. 1A and B), a symptom that usually began in the afternoon and disappeared at night, without evidence of cutaneous stigmata in the next morning. Subsequently, these lesions spread to the upper limbs, torso, and face, with concomitant asthenia and adynamia. Due to this clinical picture, the patient initially consulted to dermatology and was diagnosed with urticaria, after which medical management with antihistamines was instituted, without any improvement.

Three months after the onset of these symptoms, the patient noticed arthralgias in the hands and wrists, which predominated upon waking up, accompanied by morning stiffness, without obvious inflammatory changes, but with marked improvement over the day. Subsequently, ostealgia in the anterior region of the tibia and lymphadenopathy in the cervical chain appeared, and she continued to experience periodic chills without any predominance of time, which led to a new consultation, this time for internal medicine and rheumatology. As a result, extension studies and skin biopsy were requested, which reported histopathological changes compatible with urticaria, for which antihistamine management and short-course glucocorticoid therapy were optimized. Afterwards, she showed partial improvement, but with symptomatic resumption once the medication was withdrawn.

Afterward, the symptoms described were superimposed by the appearance of fever, which did not have a time-dependent predominance, fluctuating, and initially yielded to the administration of common antipyretics. Finally, this febrile condition became continuous and reached fever peaks of up to 40 °C, which led to consultation in the emergency room, and hospitalization in a tertiary care unit.

Upon admission, clear signs of a systemic inflammatory response were described, but with a qSOFA score of 0 and an adequate general appearance, without signs of tissue hypoperfusion, with soapy skin lesions distributed on the torso and extremities. During the hospital stay, the patient's symptoms persisted and there was febrile recurrence, despite management with antipyretics, initiating multiple broad-spectrum antibiotic management.

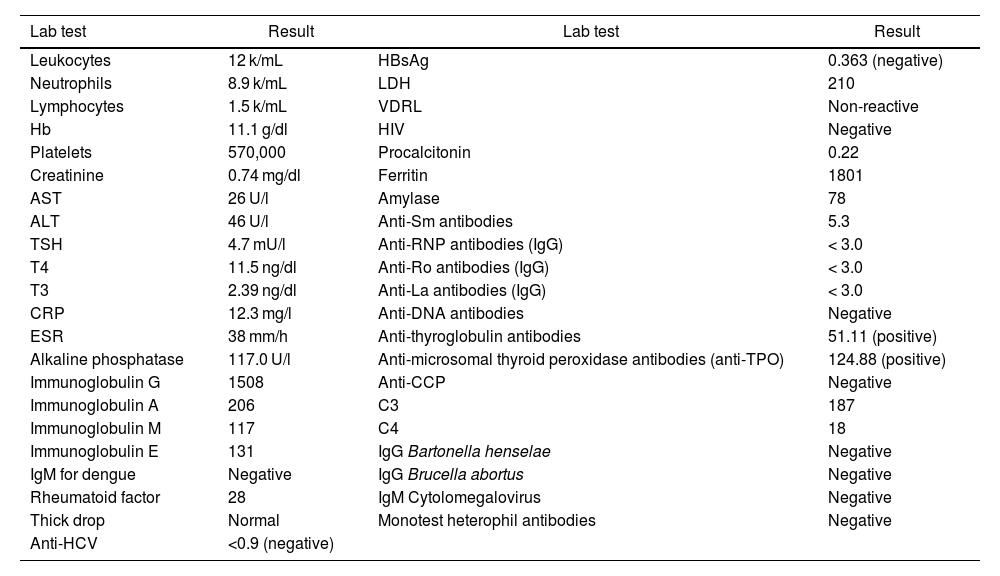

Multiple extension studies were performed, which are represented in Table 1, including a simple tomography (CT) of the chest, which showed 3.2 mm subpleural nodules in the middle and upper right lobes, possibly related to granulomas in formation, in addition to a computed axial tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, demonstrating hepatomegaly. Based on the above, a presumptive diagnosis of Still's disease was considered, but despite meeting major Yamaguchi criteria, such as fever greater than 39 °C, arthralgia, leukocytosis greater than 10,000/mm3, and neutrophilia greater than 80%, plus some minor criteria (lymphadenopathy), there were elements against it, such as the presence of skin lesions, which are not those classically described, such as an evanescent salmon-like rash. Likewise, there was a positive rheumatoid factor result with ferritin and normal liver function tests, which made this hypothesis very unlikely, especially considering that Still's disease is a diagnosis of exclusion. A bone marrow study was conducted, which showed no pathological findings, as well as protein electrophoresis in serum and urine, which found a monoclonal gamma peak and immunofixation with a monotypic IgG peak, which in the patient's clinical context constituted the diagnosis of Schnitzler syndrome, meeting 2001 Lipsker-Baltimore and 2013 Strasbourg criteria (Tables 2 and 3). Once the diagnosis was confirmed, treatment with glucocorticoids was started in conjunction with azathioprine, calcium, and vitamin D, which resulted in the disappearance of the skin lesions, cessation of febrile peaks, and the resolution of arthralgias and ostealgias.

Paraclinical tests.

| Lab test | Result | Lab test | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes | 12 k/mL | HBsAg | 0.363 (negative) |

| Neutrophils | 8.9 k/mL | LDH | 210 |

| Lymphocytes | 1.5 k/mL | VDRL | Non-reactive |

| Hb | 11.1 g/dl | HIV | Negative |

| Platelets | 570,000 | Procalcitonin | 0.22 |

| Creatinine | 0.74 mg/dl | Ferritin | 1801 |

| AST | 26 U/l | Amylase | 78 |

| ALT | 46 U/l | Anti-Sm antibodies | 5.3 |

| TSH | 4.7 mU/l | Anti-RNP antibodies (IgG) | < 3.0 |

| T4 | 11.5 ng/dl | Anti-Ro antibodies (IgG) | < 3.0 |

| T3 | 2.39 ng/dl | Anti-La antibodies (IgG) | < 3.0 |

| CRP | 12.3 mg/l | Anti-DNA antibodies | Negative |

| ESR | 38 mm/h | Anti-thyroglobulin antibodies | 51.11 (positive) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 117.0 U/l | Anti-microsomal thyroid peroxidase antibodies (anti-TPO) | 124.88 (positive) |

| Immunoglobulin G | 1508 | Anti-CCP | Negative |

| Immunoglobulin A | 206 | C3 | 187 |

| Immunoglobulin M | 117 | C4 | 18 |

| Immunoglobulin E | 131 | IgG Bartonella henselae | Negative |

| IgM for dengue | Negative | IgG Brucella abortus | Negative |

| Rheumatoid factor | 28 | IgM Cytolomegalovirus | Negative |

| Thick drop | Normal | Monotest heterophil antibodies | Negative |

| Anti-HCV | <0.9 (negative) |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; anti-CCP: anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies; anti-HCV: antibodies against hepatitis C virus; anti-TPO: anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies; Hb: hemoglobin; HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Source: Self-made.

2001 Lipsker-Baltimore diagnostic criteria for Schnitzler syndrome.

| Rash, hives, and monoclonal IgM component and at least 2 of the following criteria |

|---|

| Fever |

| Arthralgia or arthritis |

| Bone pain |

| Palpable lymph nodes |

| Enlarged liver or spleen |

| Elevated ESR |

| Leukocytosis |

| Abnormal findings in bone morphological investigations |

ESR: Erythrosedimentation rate.

Strasbourg diagnostic criterio for Schnitzler syndrome.

| Mandatory criteria |

| Chronic urticaria rash and monoclonal IgM or IgG |

| Minor criteria |

| Relapsing fever a |

| Objective findings of abnormal bone remodeling with or without pain b |

| Neutophilic dermal infiltrate in skin biopsy c |

| Leukocytosis or elevated CRP d |

| Definitive diagnosis if |

| Two mandatory criteria and at least 2 minor criteria if it is IgM and 3 minor criteria if it is IgG |

| Probable diagnosis if |

| Two mandatory criteria and at least one minor criterion if it is IgM and 2 minor criteria if it is IgG |

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; CPR: C-reactive protein.

Schnitzler syndrome is a rare acquired chronic autoinflammatory disease. The literature has reported around 300 cases in the world, few of them reported in Latin America.5 The disease manifests itself with urticarial rashes, fatigue, bone or joint pain, lymph node inflammation, and fever associated with monoclonal IgM type gammopathy; its pathophysiology is still not clear.1–3,5 The literature has reported an average age of 40–56 years, with a predominance in men.1,5,6 Our case, a young 26-year-old female patient, is a variation from what has been reported.

This case represented a diagnostic challenge due to the symptoms and the possibility of Still's syndrome; however, certain findings were unlikely related to this disorder, such as the presence of skin lesions, which are not classically described as an evanescent salmon-like rash. Additionally, there was a positive rheumatoid factor result with ferritin and normal liver function tests, which made this hypothesis very improbable. It should be noted that the combination of clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings was essential. The 2001 Lipsker-Baltimore and 2013 Strasbourg criteria were considered, in addition to the exclusion of other causes such as autoimmune hepatitis, but they were inconclusive due to normal liver function tests.

As mentioned previously, the pathogenesis of the disease is not very clearly known3–8,12; different studies refer to an alteration of the cytokine balance of innate immunity; due to its recognition as an inflammatory disorder, current research has focused on the role of IL-1β, hence immunosuppressants, such as corticosteroids, interferon α, cyclooxygenase inhibitors, anakinra (an IL-1 receptor antagonist), colchicine, cyclosporine, or thalidomide are used to control the disease.1,5,9–11,13 Due to its infrequency, there are still no studies that compare the effectiveness of the different treatments, nor has a standard therapeutic management been reported, which is why in our case we used glucocorticoids and azathioprine, obtaining good results and symptom control.

ConclusionSchnitzler syndrome is a rare disease that does not always occur in the age range usually reported in the literature; the diagnosis is essentially of exclusion and the combination of clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings, as well as multidisciplinary collaboration, is essential. Therapeutic management continues to represent a challenge, and the use of corticosteroids, as well as other immunosuppressive drugs, leads to optimal control of symptoms.

Ethical considerationsThe case report was performed under the informed consent of the family, according to resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia, guaranteeing the confidentiality of the patient's data according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants in this research were only people of legal age according to Colombian legislation, from whom written informed consent was obtained for the collection of information, data analysis, and publication of results, maintaining their anonymity throughout the process.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

FinancingNone.