Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) is an infrequent disease, of as yet unknown aetiology, which affects the retina with no systemic injury, causing progressive retinal ischaemia and visual loss. We describe the case of a Colombian patient with a diagnosis of IRVAN guided by clinical examination and diagnostic images, after previously ruling out other ocular infections, autoimmune, or systemic diseases. Our patient was treated with peripheral laser, intravitreous anti-VEGF, and systemic immunosuppression with excellent response. In conclusion, early diagnosis and proper treatment according to disease stage could improve visual prognosis.

La vasculitis retinal idiopática, aneurismas y neuroretinitis (Irvan) es una enfermedad infrecuente, de etiología aún desconocida, que afecta la retina, con el desarrollo de un cuadro típico ocular sin afectación sistémica, que llevará a isquemia retiniana progresiva y pérdida visual. En Colombia existen muy pocos casos reportados. Describimos el caso de un paciente colombiano con diagnóstico de Irvan guiado por examen clínico e imágenes, luego de descartarse otros diagnósticos infecciosos oculares o sistémicos, así como enfermedades autoinmunes. El paciente fue tratado con láser periférico, antiVEGF intravítreo e inmunosupresión sistémica, con excelente respuesta. En conclusión, Irvan es una enfermedad de descarte e infrecuente que debe ser tenida en cuenta dentro de los diagnósticos diferenciales, puesto que el diagnóstico temprano y el tratamiento según el estadio de la enfermedad podría mejorar el pronóstico visual.

Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) syndrome is an isolated and rare disease that mainly affects young patients. Its aetiology is not yet completely known; it has been described until now as a secondary vasculitis due to possible hypersensitivity to fungal or tuberculous antigens, and a genetic predisposition to develop saccular macroaneurysms with anomalous vascular flow and development of areas of non-capillary perfusion in the retina has been proposed, which generates activation in the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).1

IRVAN syndrome is characterized by retinal vasculitis (mainly phlebitis), aneurysmal dilations typically located in the first 2 arteriolar bifurcations, and neuroretinitis. Areas of peripheral capillary non-perfusion, neovascularization, and macular exudates may also be found. Although patients are usually asymptomatic, the components already described can lead to vision loss due to macular involvement or complications of retinal neovascularization (vitreous hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment, or neovascular glaucoma). Regarding treatment, the use of glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants, laser photocoagulation, and vitrectomy has been described, with variable results.2–5

The objective of the present manuscript, considering the infrequency of this entity, is to report one of the few known cases in Colombia and to review the literature regarding the topic.

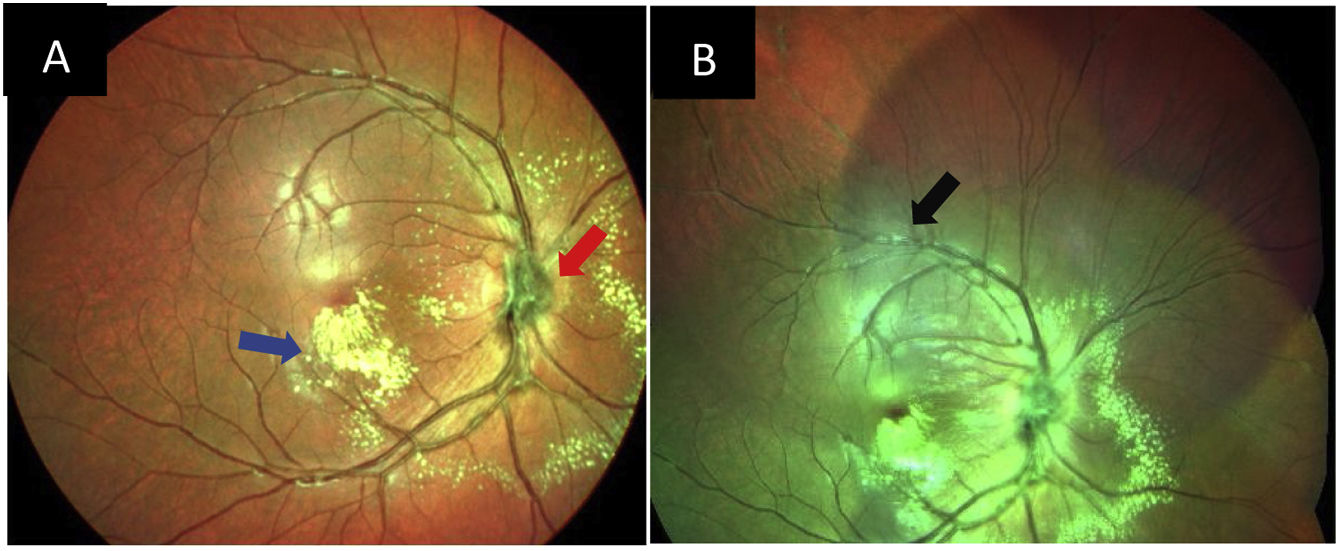

Clinical caseA 15-year-old Colombian male, with no significant medical past history, who consulted for nine months of progressive central vision loss in the left eye, with initial corrected visual acuity (VA) of 20/20 in the right eye and counting fingers at 50 cm in the left eye. The assessment of the fundus of the right eye revealed cells in the vitreous, hyperemia, and edema of the optic disc, the presence of peridiscal neovessels, microhemorrhages, macular exudates, flame hemorrhages in the lower retina, distal venous occlusions, and adhered retina (Fig. 1). The left eye presented optic nerve edema with hyperemia and neovessels, amputated peripheral vessels, and arteriovenous shunts with macular exudates like those of the contralateral eye.

Pseudocolor image of the fundus of the right eye. Optic disc edema and peridiscal neovessels (red arrow); macular exudates in 360° predominantly inferior (blue arrow, image A) and vascular sheathing (black arrow, image B) can be observed. Equipment: Spectralis HRA angiographer (Heidelberg Engineering; Heidelberg, Germany). Real photo of the patient's eye fundus. Source: Self-made.

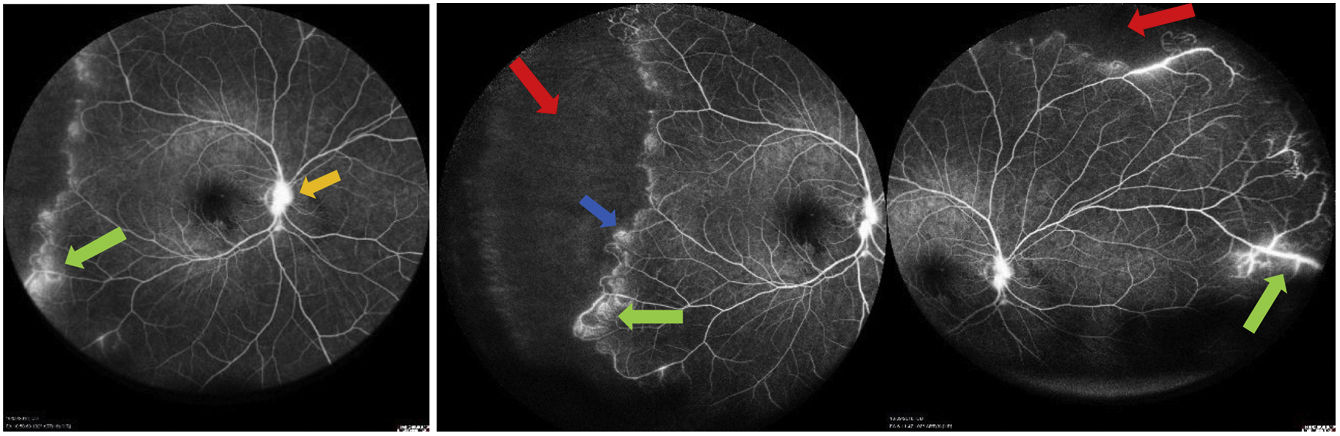

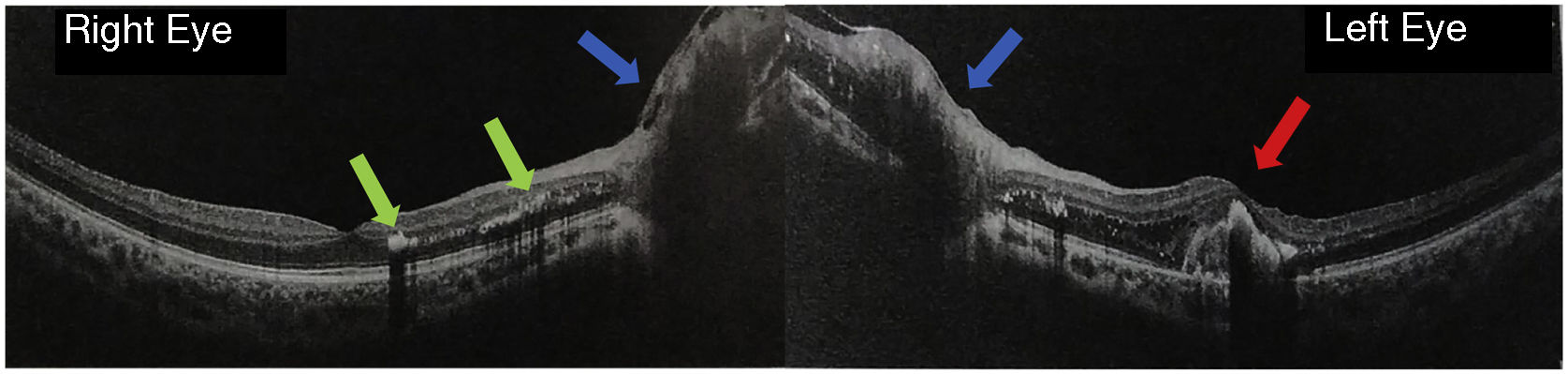

Fluorescein angiography revealed areas of retinal vasculitis, aneurysms in peripheral arteriolar bifurcations, lack of peripheral capillary perfusion, macular exudation, and bilateral optic nerve edema, as seen in Fig. 2. On macular optical coherence tomography (OCT), macular edema with cysts and intraretinal exudates was found in the outer retinal layers, predominantly on the left (Fig. 3).

FGA (fluorescein angiography). Retinal vasculitis (green arrow), bifurcation aneurysms (blue arrow), peripheral ischemia (red arrow), and macular and peridiscal exudates (yellow arrow) are evident. Equipment: Spectralis HRA angiographer (Heidelberg Engineering; Heidelberg, Germany). Real photo of the patient's eye fundus. Source: Self-made.

Macular OCT with abundant exudates in the external plexiform layer (green arrow), as well as macular edema with loss of foveal contour (red arrow). The edematous temporal edge of the optic nerve can also be seen in both eyes (blue arrow). Equipment: Optovue OCT (Optovue Inc, Freemont, CA, USA). Real photo of the patient's eye fundus. Source: Self-made.

After considering the symptoms, clinical findings, and ocular examinations described, it was concluded that the diagnosis was bilateral neuroretinitis and the patient was hospitalized for study and differential diagnosis, with negative results for IgG and IgM Toxoplasma antibodies, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), tuberculin, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (anti-PR3, anti-myeloperoxidase), complement, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAb), anti-hepatitis C, and IgG-IgM Bartonella henselae antibodies. Furthermore, creatinine, hemoleukogram, urinalysis, and cerebrospinal fluid study were normal.

After ruling out systemic and ocular infectious and considering that it was a peripheral vasculitis associated with distal vascular occlusions and ischemia, together with posterior pole exudation and optic nerve edema, the presence of IRVAN syndrome was defined. Treatment was initiated with a combination of laser photocoagulation in the retinal periphery (5 sessions), monthly intravitreal anti-VEGF injections (9 applications -bevacizumab-), a subthreshold yellow laser session – due to the persistence of macular edema – and systemic immunosuppression with methotrexate 12.5 mg every week.

In the last control performed, VA was found preserved in the right eye (20/20) and an improvement to 20/80 in the left eye was evidenced, optic discs with stable neovessels, nasal hyperemia with temporal atrophy of the left optic nerve, macular edema resolved in the right eye and still decreasing in the contralateral eye. The patient has been managed interdisciplinary by subspecialists in neuro-ophthalmology, rheumatology, uveology, and retinology, with no progression to date. It was decided to continue with anti-VEGF treatment every 2 months, due to the persistence of nasal neovascularization and exudative lesion in the left eye; in addition, laser treatment will be continued depending on the appearance of new areas of ischemia. Until the last follow-up, the patient showed adequate tolerance to the treatments.

Topic reviewIn IRVAN syndrome, retinal vascular inflammation develops, most frequently phlebitis-type, which is clinically observed as an increase in vascular diameter with sheathing of the wall. Although arteriolar inflammation with vascular sheathing is rare, arterial inflammatory involvement is frequently observed with multiple aneurysmal dilations. Both vascular alterations described lead to hemorrhagic exudation, macular edema, non-perfusion areas, formation of collateral vessels, and neovascularization.1,4,6 The presentation is usually bilateral, but there are unilateral case reports.7

Tumor necrosis factor alpha has been proposed as an important causative agent of inflammation in these patients, which can lead to tissue destruction. Among the little information that has been reported in histopathological assessment due to the limited availability of samples, fibrinoid thrombosis without cellular response is described.1,4,6

The development of vascular dilation is because the segment of the vascular wall affected by inflammation dilates, in response to intravascular hydrostatic pressure, and forms ectasia and aneurysm. Several studies have reported that the number and morphology of aneurysms change during the disease due to migratory inflammatory reaction in the vessels, so that, as the inflammation resolves, the strength of the vascular wall can be recovered so that the size of the aneurysm is reduced or even disappears. This inflammatory process can extend to the choroidal vessels, which can simulate different inflammatory and infectious entities.6

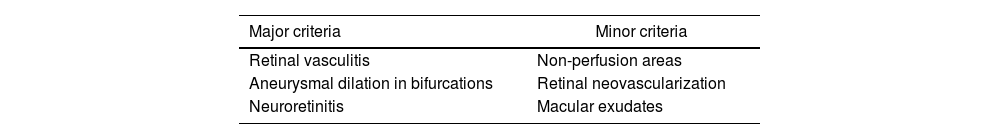

Neuroretinitis is characterized by acute vision loss secondary to inflammation of the optic nerve, accompanied by exudates arranged in a star shape around the fovea. The classification is based on major and minor criteria, according to the clinical characteristics described in Table 1.1

Diagnostic criteria for IRVAN síndrome.

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| Retinal vasculitis | Non-perfusion areas |

| Aneurysmal dilation in bifurcations | Retinal neovascularization |

| Neuroretinitis | Macular exudates |

Additionally, classification by stages has been proposed based on the progression of the disease: stage 1 corresponds to the presence of macroaneurysms, macular exudates, and neuroretinitis; stage 2 includes angiographic evidence of areas of non-perfusion. In stage 3, neovascularization occurs in the optic nerve or any other retinal area (or vitreous hemorrhage). In stage 4, neovascularization is observed in the anterior segment, while stage 5 corresponds to progression to neovascular glaucoma.

Imaging plays an important role in diagnosis, monitoring inflammation, and response to treatment, as well as detecting the development of complications.1,7

Fluorescein angiography shows contrast leakage in the vessels, affected proportionally to the inflammatory activity, while aneurysmal dilations are observed as extensive arteriolar leakage with late staining. For its part, ischemia reveals areas of non-perfusion in the periphery or the macula; macular edema manifests with diffuse hyperfluorescence that increases in late phases and, similarly, neuroretinitis produces hyperfluorescence of the optic nerve head with or no staining in late phases.1

Indocyanine green angiography (not available in Colombia) is particularly useful in demonstrating specific patterns of aneurysms and is seen as well-delineated dilations throughout the examination with retinal hypercyanescence without leakage. Large dilated and leaky choroidal vessels are also seen in the early to intermediate phase, which may indicate a vasculitic component.1

Macular OCT is very useful in detecting changes in the macula, even early subclinically. Vitreomacular traction with an epiretinal membrane is observed, and macular edema characterized by diffuse thickening or macular exudation with hyperreflective lesions that generate shadow.1,7

Treatment depends on the progression and presentation of the disease: subjects in stages 1 and 2 are managed with oral steroids and systemic immunomodulation, without complete success in most reported cases; furthermore, if macular ischemia is present, the visual result will be poor, regardless of whether the control of inflammation is successful.5

In stage 3, it is necessary to add local treatment with laser or cryotherapy in the avascular retina, with or without application of intravitreal anti-VEGF; however, if in stage 2 the non-perfusion areas occupy more than 2 quadrants, they also require laser photocoagulation. Early vitrectomy is performed to manage complications such as vitreous hemorrhage and tractional retinal detachment.5

Regarding prognosis, the reported literature still does not support that management with steroids can resolve retinal lesions, but the response depends largely on the stage of the disease at the beginning of treatment.2 Persistent progression of retinal ischemia due to capillary non-perfusion, retinal neovascularization, and exudates in the macular region can cause severe and irreversible vision loss if treatment is not initiated.

DiscussionWe found an important contribution of this case to the literature since a differential diagnosis could be made with other autoimmune and infectious diseases that cause retinal vasculitis; in addition, an adequate work-up was carried out with multimodal images that helped to support the diagnosis of IRVAN syndrome and to objectify the improvement with treatment. Different therapeutic approaches such as retinal laser, intravitreal treatment with anti-VEGF, and systemic treatment with immunomodulators could be used. However, the reporting of this disease has limitations due to the lack of previous publications and the absence of treatment guidelines and protocols.

In the first report by Owens and Gregor in 1992, arterial aneurysms, macular edema, and neovascularization were described, without a systemic cause of the vasculitis as occurred in our case.8 In 1999, Sashihara et al. described a case with similar clinical findings and suggested, for the first time, that aneurysms were associated with arterial inflammation. Furthermore, to some extent, they also suspected regression or fading of the aneurysm after treatment.9

Yeshurun et al. described not only the regression of aneurysms after laser photocoagulation but also its resolution as part of the natural course with or without photocoagulation. In the current case, the patient regressed with therapy, as in the case described by Tomita et al. in 2003, in which there was improvement in both fundus findings and vision after therapy.10,11

In 2004, Abu El-Asrar et al. reported two subjects with allergic fungal sinusitis and IRVAN syndrome that showed regression after treatment of sinusitis with steroids, which they suggested a fungal hypersensitivity reaction as a common trigger; however, it was probably that the use of steroids improved both disorders. Kumawat and Kumar reported, in 2018, a stage 2 IRVAN syndrome with a very good response to glucocorticoid monotherapy. Our patient is in stage 3 and, although he does not receive treatment with steroids, immunosuppression with methotrexate combined with other measures, such as retinal laser and anti-VEGF were started.2,12

In 2016, Singh et al. suggested that IRVAN syndrome may be a morphological diagnosis associated with different entities, since they reported a female patient with a diagnosis of IRVAN syndrome and a positive tuberculin skin test (confirmed in vitreous), who had successful regression with antituberculous therapy combined with steroids. The patient currently reported has a negative tuberculin test; however, we agree on ruling out intraocular tuberculosis in cases of endemic population.13

In conclusion, IRVAN syndrome is a rare clinical entity, which ends up being a rule-out diagnosis, characterized by a progressive course of retinal ischemia and visual impairment. Early diagnosis, based on the ophthalmological examination and multimodal images, will help choose the appropriate treatment for each patient, trying to control the progression of the disease and its visual sequelae.

Informed consentInformed consent was requested from the guardian, since the patient is a minor, with acceptance from the patient. It was not considered necessary to request authorization from the institution's ethics committee since none of the studies or treatments conducted are part of ongoing research or clinical trials. The authors declare that this article does not contain personal information or photographic records that would allow the patient to be identified.

FinancingThe authors declare that they have not received funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.