Fibromyalgia is a chronic disease characterized by musculoskeletal pain associated with other symptoms. Its etiology is unknown, diagnosis is clinical and treatments are symptomatic. How patients face the diagnosis and pain and how it appears to influence their evolution and treatment.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the effect of catastrophising and anxiety to pain regarding functional ability and consumption of drugs in patients with fibromyalgia.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional study of 50 patients fibromyalgia cited in rheumatology from January 1 to March 31 of 2014 and volunteers of the Association of Patients with Fibromyalgia Asturias. Clinical and epidemiological variables, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire abbreviated (FIQ), Pain Catastrophising Scale (PCS) and Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS-20) were recorded.

ResultsThe Spearman correlation between PCS-SP and PASS-20 was 0.67 (p<0.001) between CIF and PASS-20 0.27 (p=0.05) and between CIF and PCS-SP 0.03 meaningless statistics. The correlation with the consumption of drugs was: with PASS-20 0.41 (p=0.003), with PCS-SP 0.49 (p<0.001) and with CIF 0.32 (p=0.024). The correlation coefficient from the onset of symptoms was: −0.21 (p=0.14) with CIF, −0.16 (p=0.26) with PCS and −0.25 (p=0.08) with PASS-20.

ConclusionsThe levels of anxiety and catastrophising are strongly associated with each other, but both show a weak association with functional capacity. High scores on three scales represented an increase in consumption of drugs. A longer history of fibromyalgia appears to decrease the level of anxiety, catastrophising and functional impact.

La fibromialgia es una enfermedad crónica, caracterizada por dolor musculoesquelético asociado a otros síntomas. Se desconoce su etiología, el diagnóstico es clínico y los tratamientos sintomáticos. El cómo afrontan los pacientes este dolor y su diagnóstico parece influir sobre su evolución y tratamiento.

ObjetivoEvaluar el efecto de la catastrofización y ansiedad ante el dolor, sobre la capacidad funcional y el consumo de fármacos de los pacientes con fibromialgia.

Materiales y métodosEstudio transversal de 50 pacientes con fibromialgia, citados en reumatología desde el 1 de enero hasta el 31 de marzo de 2014 y voluntarios de la Asociación de Enfermos de Fibromialgia de Asturias. Se registraron variables clínico-epidemiológicas, Cuestionario de Impacto de la Fibromialgia abreviado (CIF), Escala de Catastrofización Ante el Dolor (PCS-SP) y Escala de Síntomas de Ansiedad Ante el Dolor (PASS-20).

ResultadosLa correlación de Spearman entre PCS-SP y PASS-20 fue de 0.67 (p<0.001), entre CIF y PASS-20 de 0.27 (p=0.05) y entre CIF y PCS-SP de 0.03, sin significación estadística. La correlación con el consumo de fármacos fue: con PASS-20 0.41 (p=0.003), con PCS-SP 0.49 (p<0.001) y con CIF 0.32 (p=0.024). El coeficiente de correlación desde el inicio de los síntomas fue: −0.21 (p=0.14) con CIF, −0.16 (p=0.26) con PCS y −0.25 (p=0.08) con PASS-20.

ConclusionesLos niveles de ansiedad y catastrofización se encuentran fuertemente asociados entre sí, sin embargo, ambos muestran una asociación débil con la capacidad funcional. Puntuaciones altas en las 3 escalas supusieron un aumento del consumo de fármacos. Con mayor tiempo de evolución de la fibromialgia parece disminuir el nivel de ansiedad, la catastrofización y la repercusión funcional.

Fibromyalgia is a rheumatologic chronic disease, recognized in 1992 by the World Health Association.1 It is a complex disorder characterized by acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain, for at least 3 months, which can become very disabling. Other associated symptoms such as morning joint stiffness, fatigue, headache, alterations in sleep, concentration and memory, as well as emotional disorders may occur, so that up to 60% of patients suffer from anxious-depressive disorders.2,3

In Spain is estimated that 2.4% of the population older than 20 years suffer from it, with a 20/1 female/male ratio.4 Its high rate in ages of working activity implies a great socio-sanitary repercussion, because patients have limitations and aggravation of the symptoms in their work routine.5

The diagnosis is difficult and imprecise, since there are no specific laboratory tests and it is based on the clinic and the physical assessment.6 There are different scales that allow to evaluate the impact of FM on the functional capacity, the quality of life and the psychosomatic repercussion. One of the most commonly used is the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) (in its Spanish version: CIF, Cuestionario de Impacto de la Fibromialgia)7; others that complement the diagnosis by addressing the psychological sphere and coping with pain are the Pain Catastrophising Scale (PCS-SP)8 and the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS-20).9

Currently, there are drugs that can control the symptoms and improve the quality of life of these patients, but none of them can cure the disease, and for this reason it is the pathology of soft tissue that more consultations generates in the Health Centers of the Country, with great economic cost due to the interconsultations carried out and the consumption of medicines.10 The affected individuals attend an average of 9–12 annual medical visits, make greater use of alternative therapies and entail important costs in terms of labor absenteeism and litigations. Also, they undergo a greater number of surgical interventions.11

For this reason, the management should be based on a multidisciplinary approach adequate for each patient, combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies.12,13 The use of complementary therapies is becoming more and more frequent worldwide and is highly related to the time of evolution of the disease.14–16 Among them, there are studies that endorse the benefits of the cognitive behavioral therapy, which reduces significantly the perception of pain, sleep problems, depression and catastrophism; in addition to improving the functional status, the operant cognitive therapy appears to decrease the number of medical visits17 and the supervised exercises seem to improve the functional capacity.18 Such multidisciplinary approach is not only competence of the primary and specialized care physician but also of the nursing professionals, who are involved in the sanitary education, group therapies, counseling, increase of coping skills and behavior modification, among many other competencies.15,19

The objective of this work is to evaluate the impact of the catastrophising and anxiety to pain on the functional capacity and the consumption of medicines in the patients with fibromyalgia. As secondary objectives, it was assessed the association of the 3 scales with the diagnosis of depression, type of cohabitation, educational level, time of evolution of the symptoms, time since diagnosis and participation in alternative therapies.

Materials and methodsIt is a cross-sectional study of 50 patients with fibromyalgia, cited in Rheumatology and Internal Medicine at the Hospital de Cabueñes of Gijon, from January 1 until March 31, 2014, and participants of the Association of Patients with Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue of Asturias, in this period.

Clinical and epidemiological data collected from the hospital paper medical records and from the computer program Selene were recorded: gender, age, race, nationality, cohabitation, educational level, working status, profession, consumption of tobacco and alcohol, onset of the symptoms, year of diagnosis, other diseases, treatments for fibromyalgia, psychopharmaceutical drugs, rehabilitation treatments and alternative therapies.

The patients were contacted by telephone and convoked in the Service of Rheumatology of the Hospital de Cabueñes. At that time they completed the informed consent, the evaluation tests and the missing data in the paper medical records. They also answered the following open-ended questions: “What are your main symptoms of fibromyalgia currently?” and “do you think that there was a trigger for the disease?”.

The self-administered tests validated in Spanish were:

- 1.

CIF: it was used its first item that evaluates the functional capacity perceived by the patient. It consists of 10 sub-items that score between 0 and 3; the total value divided by the number or responses was normalized to obtain a value between 0 and 10 multiplying it by 3.33, with 0 being the best functional capacity and 10 being the worst.

- 2.

PCS-SP: which explores the catastrophic thinking (rumination, magnification and defenselessness) in relation to pain, with 13 items. Its value ranges between 13 and 62.

- 3.

PASS-20: which explores the fear of pain and the behavior of escape/avoidance associated with pain, by means of 20 items. Its value ranges from 0 to 80.

A descriptive summary of the variables was made according to conventional statistical techniques: proportions for nominal categorical variables, measures based on ordinations (medians and interquartile ranges) for ordinal variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion, based on moments, for quantitative variables of interval or ratio. The possible associations were studied using nonparametric tests: Wilcoxon test, Spearman's correlation and Kruskal–Wallis test of ranges. The analyses were performed using the statistical program Stata/IC 13.1.

The necessary measures for protection of data of personal character of all the clinical information were adopted and the access to data complied with the regulations of the center from where they were collected. In addition, informed consent was requested to all participants in order to comply with the ethical standards for clinical research.

ResultsThere were registered 68 medical records of patients with diagnosis of fibromyalgia, according with the criteria or the American College of Rheumatology of 1990, 60 who have attended the consultation of Rheumatology in the Hospital de Cabueñes in the first quarter of 2014 and 8 who were recruited after the voluntary invitation to a group of patients who attended in this quarter the Association of Patients with Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue of the Principality of Asturias.

Three did not met the criteria for inclusion since they referred that they did not have a confirmed diagnosis, 5 patients refused to participate, 4 were traveling, 3 could not be contacted and the remaining 3 alleged family circumstances. Finally, 50 patients were included in the study.

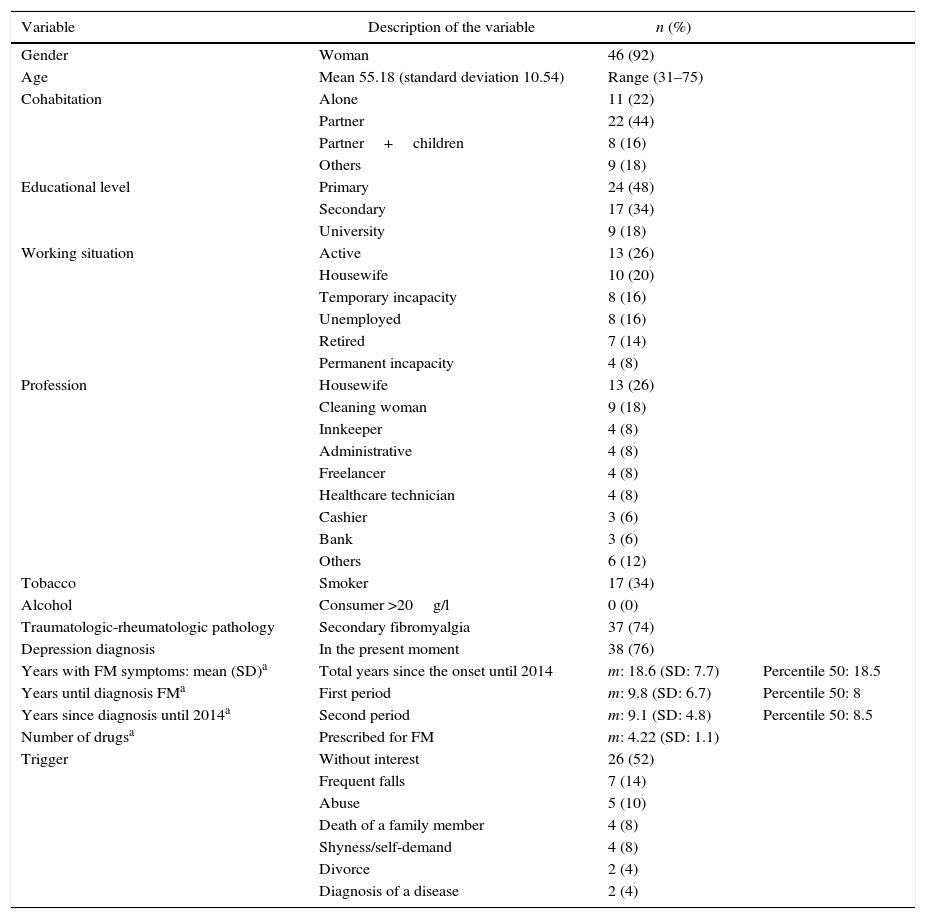

The analysis revealed that 92% (n=46) were women, with an average age of 55.2 years (SD: 10.54) (range 31–75), who live with a partner in 44% (n=22) with a level of primary studies in 48% (n=24) of cases. 74% (n=37) had a history of trauma or rheumatologic pathology associated with chronic pain such as osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, and 76% (n=38) were diagnosed with depression at the time of the study.

33 patients of working age were registered, of whom 36.4% (n=12) were in a situation of temporary or permanent incapacity due to their disease.

The patients had developed the first symptoms in an average of 18.8 years (SD: 7.7), before the time of the study. The time elapsed until diagnosis had an average of 9.8 years (SD: 6.7), The time between the onset of the symptoms and the time of diagnosis showed an average of 9.1 years (SD: 4.8). The clinical and epidemiological characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Clinical and epidemiological variables of the patients with fibromyalgia (n=50).

| Variable | Description of the variable | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Woman | 46 (92) | |

| Age | Mean 55.18 (standard deviation 10.54) | Range (31–75) | |

| Cohabitation | Alone | 11 (22) | |

| Partner | 22 (44) | ||

| Partner+children | 8 (16) | ||

| Others | 9 (18) | ||

| Educational level | Primary | 24 (48) | |

| Secondary | 17 (34) | ||

| University | 9 (18) | ||

| Working situation | Active | 13 (26) | |

| Housewife | 10 (20) | ||

| Temporary incapacity | 8 (16) | ||

| Unemployed | 8 (16) | ||

| Retired | 7 (14) | ||

| Permanent incapacity | 4 (8) | ||

| Profession | Housewife | 13 (26) | |

| Cleaning woman | 9 (18) | ||

| Innkeeper | 4 (8) | ||

| Administrative | 4 (8) | ||

| Freelancer | 4 (8) | ||

| Healthcare technician | 4 (8) | ||

| Cashier | 3 (6) | ||

| Bank | 3 (6) | ||

| Others | 6 (12) | ||

| Tobacco | Smoker | 17 (34) | |

| Alcohol | Consumer >20g/l | 0 (0) | |

| Traumatologic-rheumatologic pathology | Secondary fibromyalgia | 37 (74) | |

| Depression diagnosis | In the present moment | 38 (76) | |

| Years with FM symptoms: mean (SD)a | Total years since the onset until 2014 | m: 18.6 (SD: 7.7) | Percentile 50: 18.5 |

| Years until diagnosis FMa | First period | m: 9.8 (SD: 6.7) | Percentile 50: 8 |

| Years since diagnosis until 2014a | Second period | m: 9.1 (SD: 4.8) | Percentile 50: 8.5 |

| Number of drugsa | Prescribed for FM | m: 4.22 (SD: 1.1) | |

| Trigger | Without interest | 26 (52) | |

| Frequent falls | 7 (14) | ||

| Abuse | 5 (10) | ||

| Death of a family member | 4 (8) | ||

| Shyness/self-demand | 4 (8) | ||

| Divorce | 2 (4) | ||

| Diagnosis of a disease | 2 (4) |

SDE: standard deviation and percentile 50; m: mean.

7 different responses were obtained regarding the trigger: 52% (n=26) do not associate it with any event from the past, 14% (n=7) link it with clumsy childhood and youth, being patients who presented many falls, 10% (n=5) tell the story of some type of family or work abuse that triggered the first symptoms, 8% (n=4) associated it with the death or a family member and another 8% (n=4) to a demanding and shy personality in their youth, 2 patients (4%) made reference to a divorce and another 2 to the diagnosis of another disease (4%).

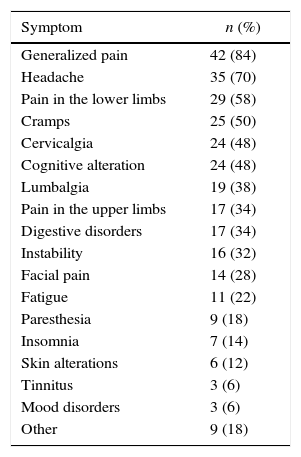

The symptomatology most often reported by the patients was in 84% (n=42) generalized pain, headache in 70% (n=35), pain in lower limbs in 58% (n=29), cramps in 50% (n=25) and cervicalgia and cognitive alterations such as loss of memory or lack of concentration, in both cases with a frequency of 48% (n=24) (Table 2).

Referred symptomatology associated with fibromyalgia (n=50).

| Symptom | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Generalized pain | 42 (84) |

| Headache | 35 (70) |

| Pain in the lower limbs | 29 (58) |

| Cramps | 25 (50) |

| Cervicalgia | 24 (48) |

| Cognitive alteration | 24 (48) |

| Lumbalgia | 19 (38) |

| Pain in the upper limbs | 17 (34) |

| Digestive disorders | 17 (34) |

| Instability | 16 (32) |

| Facial pain | 14 (28) |

| Fatigue | 11 (22) |

| Paresthesia | 9 (18) |

| Insomnia | 7 (14) |

| Skin alterations | 6 (12) |

| Tinnitus | 3 (6) |

| Mood disorders | 3 (6) |

| Other | 9 (18) |

Variables collected from the open-ended question: “Which are your main symptoms of fibromyalgia currently?”.

The mean of the patients who consumed medicines prescribed for their fibromyalgia was 4.22 (SD: 1.1), with 90% (n=45) being consumers of minor analgesics, 42% (n=21) consumers of minor opioids and 40% (n=20) consumers of antiepileptic drugs. 78% (n=39) participated in alternative therapies and 54% (n=27) were users of rehabilitation programs. 52% (n=26) were consumers of psychopharmaceutical drugs, the most commonly prescribed were the inhibitors of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake by 28% (n=14) and selective for serotonin by 20% (n=10). Trazodone was prescribed in 14% (n=7) and tricyclic antidepressants in 10% (n=5). Only one patient reported that was not taking any drug for fibromyalgia.

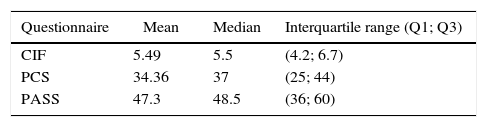

In the CIF scale was obtained a median of 5.5 (interquartile range [IR]: 4.2; 6.7) of the total of 10 points. The PCS-SP scale scored a median of 37 (IR: 25; 44) of 62 points. The PASS-20 scale yielded a median of 48.5 points (IR: 36; 60) of a maximum of 80 (Table 3).

Results of the scoring in the CIF, PASS-20 and PCS-SP.

| Questionnaire | Mean | Median | Interquartile range (Q1; Q3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIF | 5.49 | 5.5 | (4.2; 6.7) |

| PCS | 34.36 | 37 | (25; 44) |

| PASS | 47.3 | 48.5 | (36; 60) |

CIF: Cuestionario de Impacto de la Fibromialgia (Spanish version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire); PASS-20: Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale; PCS-SP: Pain Catastrophising Scale, Spanish version.

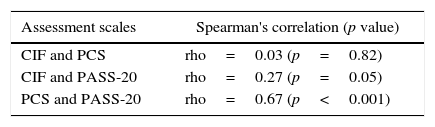

The correlation coefficients were the following (Table 4); between the CIF and PCS-SP it was 0.03 (p=0.82) and between the CIF and PASS-20 it was 0.27 (p=0.05). Between PCS-SP and PASS-20 it was 0.67, being statistically significant (p<0.001).

Associations between the scores of CIF, PASS-20 and PCS-SP and their relationship with other studied variables.

| Assessment scales | Spearman's correlation (p value) |

|---|---|

| CIF and PCS | rho=0.03 (p=0.82) |

| CIF and PASS-20 | rho=0.27 (p=0.05) |

| PCS and PASS-20 | rho=0.67 (p<0.001) |

| Variables | CIF | PASS-20 | PCS-SP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption of drugsa | rho=0.32 | rho=0.41 | rho=0.49 |

| (p=0.024) | (p=0.003) | (p<0.001) | |

| Time with symptomsa | rho=−0.21 | rho=−0.25 | rho=−0.16 |

| (p=0.14) | (p=0.08) | (p=0.26) | |

| Time since they were diagnoseda | rho=0.03 | rho=−0.14 | rho=−0.13 |

| (p=0.86) | (p=0.35) | (p=0.34) | |

| Depression | No statistically significant association was found | ||

| Use of alternative therapiesb | No statistically significant association was found | ||

| Cohabitationb | No statistically significant association was found | ||

| Educational levelb | No statistically significant association was found | ||

CIF: Cuestionario de Impacto de la Fibromialgia (Spanish version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire); PASS-20: Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale; PCS-SP: Pain Catastrophising Scale, Spanish version.

rho: Spearman's correlation coefficient.

It was found a statistically significant positive linear relationship between the number of drugs and the 3 scales: between the number of drugs and the CIF it was 0.32 (p=0.024), with the PCS-SP it was 0.49 (p<0.001) and with PASS-20 it was 0.41 (p=0.003).

The correlation coefficient between the time elapsed since the year of diagnosis and the time of the study was: with CIF 0.03 (p=0.86), with PCS-SP −0.13 (p=0.34) and with PASS −0.14 (p=0.35). The linear correlation coefficient between the time with symptoms and the scales was: −0.21 (p=0.14) with CIF, −0.16 (p=0.26) with PCS-SP and −0.25 (p=0.08) with PASS-20.

No statistical relationship was found between the scales and the existence of depression, cohabitation, the educational level or the use of alternative therapies.

DiscussionFibromyalgia is a complex disease that often generates negative feelings in the healthcare professionals because of the difficulty for objectifying the inability, deficiencies in the assessment tools and the poor effectiveness of the treatments.20 The approach is usually focused on correcting the chronic pain and the functional limitation, but it is important not to forget the repercussion of this chronic pain on the psychopathological sphere and the benefits of promoting the cognitive construct of acceptance.

In our sample, the patients make clear a degree of anxiety and catastrophising to moderate pain, which gets to be severe in some cases. Both levels are strongly associated with each other and entail an increase in the consumption of medicines. A relevant association with the functional capacity was not found. These data are consistent with the statements of J. García Campayo21 about how the acceptance is not associated with a lower level of pain but rather with a greater cognitive work. As well as many of the actions intended to eliminate the acute pain have, in the long term, very damaging consequences for the quality of life of the patients, because they are ineffective in chronic pain, generating a decrease in activity that can lead to abandonment of work, continued increase in medication whose side effects end up being disabling, etc.

The first step for a correct approach of the psychopathological sphere is to make and early and correct diagnosis. There are controversies regarding the convenience of giving the diagnosis, and which would be the most adequate type of attention and follow-up. In our study, a longer time from diagnosis favors a decrease of catastrophism and anxiety to pain, and having symptoms for a longer time appears to be related, in addition, to a greater functional capacity. This is consistent with a systematic review,22 with a level of evidence of moderate–good quality, which indicates that it reduces the attendance pressure by these patients. As well, Escudero-Carretero et al.23 state that half of the patients who receive a diagnosis of fibromyalgia have a remission of the symptoms after 2 years without taking medication. Likewise, Burchkhard et al.24 observed an increase in the level of physical activity and a significant improvement in the self-efficacy and quality of life, and Oliver et al.25 describe a decrease of catastrophism, although the rest of the measured variables did not show significant changes.

With such evidence, it would be interesting to conduct studies that analyze in an isolated manner the effectiveness of education in fibromyalgia, addressed fundamentally to promote the cognitive construct of acceptance, its therapeutic adherence and its cost/benefit. As well is important to know how to differentiate between those patients who try to get a sick leave simulating pain,26 and those who improve clinically when they know the diagnosis by tackling the disease through the rational use of drugs, positive coping strategies, alternative therapies and participation in associations.23 Hence the interest in incorporating into the clinical practice the use of validated questionnaires that assess the psychopathological sphere, as well as the recognition of catastrophism and acceptance as cognitive constructs that are determinants to predict the evolution of the patient.21

Approximately half of the patients of our sample could be classified in type III, according to the classification of Belenguer, a subgroup that somatically manifests an underlying psychopathological process, including affective and personality characteristics that make them channelize their psychological problems in pain. 4 patients who directly linked their disease with their avoidant, dependent, obsessive or very self-demanding personality traits stood out, coinciding with the literature that reports that these patients usually exhibit a general maladjustment, feelings of personal immaturity and subjective stress, being advisable to evaluate them by mental health.26 Other 5 patients linked it with affective disorders, referring histories of abuse, coinciding with other authors who speak of probable biological, psychological and social predisposing factors that trigger and perpetuate the disease.27

It also draws attention to the high degree of comorbidity with depression presented by the patients, data that is consistent with the study of Raphael et al.28 which states that the risk of developing a major depressive disorder was 3 times higher in patients with fibromyalgia and that the risk of suffering from anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders was 5 times higher. Although it did not appear to be related with a higher level or catastrophism or anxiety to pain, and the impact of fibromyalgia on their functional capacity was not greater. It would be necessary to carry out studies that evaluate chronic emotional factors as a risk factor for fibromyalgia.

The labor impact of fibromyalgia seems to be strongly influenced by the psychopathological comorbidity,29 therefore, not only this sphere of the disease should be properly addressed, but it would be interesting that patients have access to legal advice regarding their labor situation, in order to arrange jobs compatible with their pathology so they would not have to interrupt their activity during the periods of exacerbation of the disease, as it occurs in 1/3 of our sample, data similar to other studies where it is estimated that it affects between 1/4 and 1/2 of patients with fibromyalgia.5,30

Patients should receive clear symptomatic pharmacological guidelines, with continued monitoring, to be suspended in those cases where they do not provide any benefit. Likewise, treatment should be individualized, including in each case information about non-pharmacological therapies based on scientific evidence, such as supervised exercises or the cognitive-behavioral therapy, since patients are very prone to this type of therapies, to which they keep a very good adherence and from which they refer to benefit in many cases. Although initially our study did not find any relationship between their use and the scores in the evaluated scales, we did not delve into the types of therapies referred by the patients and their repercussions on other levels were not analyzed either. And, finally, it is important that the prescribed treatments do not promote the passivity of the patient since it has proven to be detrimental to a good performance. The belief that “patients cannot function while suffering pain” not only appears to be not true, but it also seems to be harmful.21

The limitations of this study are the diffuse nature of the factors favoring fibromyalgia and not having established diagnostic subgroups in order to know the repercussion of each type on the results of the evaluated tests. They would be interesting future lines of research that would analyze the scores of these questionnaires on an exclusive sample of type III patients, according to the classification of Belenguer. In addition, we incurred in an enrollment bias since the 8 patients recruited in the association were volunteers, but their clinical and demographic characteristics did not show relevant differences so they did not alter the homogeneity of the sample.

The main strength of our study is its approximation to some psychopathological traits of the disease. In addition, it uses diagnostic tools for quick and easy completion that can be incorporated easily into the routine clinical practice of primary and specialized care.

We obtained a high degree of participation of the contacted patients, and having made personalized interview, there were no losses in the data collected. Finally, the fact that the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of our study group coincide with those of the existing literature, favors a good external validity.

In conclusion, the analyzed patients with fibromyalgia present an impact of the disease on their mild-moderate functional capacity and a moderate level of catastrophising and anxiety to pain that gets to be severe in some cases. Both negative coping with pain are strongly associated, but having a weaker repercussion on their functional capacity. Although the increased anxiety, catastrophising and functional disability are associated with an increase in the consumption of drugs, so that addressing the psychopathological sphere should be taken into account in the therapeutic approach, and not only the functional repercussion. On the other hand, a longer time of evolution of the fibromyalgia seems to decrease the levels of catastrophising and anxiety to pain, so the first step for this positive coping would be to promote early diagnosis.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on human beings or animals for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred in the article. This document is held in the possession of the corresponding author.

FundingThis project did not receive any funding source.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

To the Association of Patients with Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue of the Principality of Asturias and to all who participated in the study.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Fernández AM, Gancedo-García A, Chudáčik M, Babío-Herráiz J, Suárez-Gil P. Estudio transversal del efecto de la catastrofización y ansiedad ante el dolor sobre la capacidad funcional y el consumo de fármacos en pacientes con fibromialgia. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2016;23:3–10.