Neurological paraneoplastic syndromes occur in less than 1% of solid tumours and are uncommon in lymphomas. They are related to tumours with high biological activity and cause functional impairment and disability. Dermatomyositis is associated with cancer, and requires the study of hidden neoplasms. Its diagnosis as a paraneoplastic syndrome is established with specific criteria. Functional prognosis depends on early diagnosis, cancer control, and regulation of the immune response. The case is presented of a 65 year-old woman with dermatomyositis during the course of a conventional variant of a primary cutaneous B marginal lymphoma.

Los síndromes paraneoplásicos neurológicos se presentan en menos del 1% de los tumores sólidos y son infrecuentes en linfomas. Se asocian a tumores con alta actividad biológica y condicionan deterioro funcional y discapacidad. La dermatomiositis se asocia a cáncer, por tanto obliga al estudio de neoplasias ocultas; su diagnóstico como síndrome paraneoplásico se establece con criterios específicos. El pronóstico funcional depende del diagnóstico oportuno, control del cáncer y de la regulación de la respuesta inmunológica. Se presenta el caso de una mujer de 65 años con dermatomiositis en el curso de un linfoma B marginal variante convencional de primario cutáneo.

Neurological paraneoplastic syndromes (PNS) develop in at least 1/10,000 patients with cancer, and are the result of the remote effect of the neoplasm.1 The frequency of presentation is less than 1% in solid tumors, with the higher rates found in lung, breast, ovarian and colorectal cancers. There is a lower incidence in pancreas, stomach, gallbladder, and hematolymphoid malignancies.2,3 The incidence of malignant disease in patients with potential PNS depends on the type of disorder, ranging from 5 to 60%, but in almost 80% of the patients PNS presents months or even years before cancer is diagnosed.1

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an autoimmune inflammatory disease, characterized by symmetrical proximal myopathy and cutaneous manifestations.1 DM is associated with up to a 6-fold increased risk of cancer4; its incidence is 1/100,000, with 15-30% of the cases being paraneoplastic.5 In 40% of the cases DM presents before the development of cancer, in 26% is concurrent, and in 34% presents after any cancer manifestations.1,3,4

The diagnosis of DM and PNS is made according to specific criteria and the treatment focuses mainly on cancer control3 and on immune response modulation.1 This article discusses the clinical evolution and the diagnostic strategies in the case of a 65-year old patient with DM and accelerated functional impairment. A conventional variant of a primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma was confirmed, and the clinical results following diagnosis and treatment are presented.

Patient descriptionThis is a 65-year old female admitted in May 20, 2016 after experiencing constitutional symptoms for 4 months, including evening fever, weight loss, nocturnal diaphoresis, and over the last 2 months she developed generalized, dermatological erythematous plaque lesions with pruritus, associated with myalgia and progressive muscle weakness; at the time of admission the patient was unable to walk. She had a history of ovarian cancer 19 years earlier, which was treated then, and did not present any neurological involvement. The initial physical examination revealed heliotrope rash, erythematous-violaceous plaques in the chest and upper extremities, sparing the scalp and lower limbs. The initial oncology assessment on May 24 identified mild motor dysphagia, muscle weakness in the 4 extremities - primarily proximal -, with 2/5 muscle strength in the shoulder and pelvic girdle, and distal muscle strength of 3/5 in Daniels’s scale. A suspicious myopathy prompted the determination of muscle enzymes that showed a creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) of 10,552U/L. The electrophysiological assessment evidenced a myopathic pattern with significant muscle denervation and a quantitative electromyographic interference pattern of 75% abnormality of the motor units studied, which was the basis for the clinical suspicion of inflammatory myopathy.

In view of the significant potential PNS-related functional impact, immunomodulation therapy was initiated on May 26, with clinical functional follow-up and muscle enzymes control (CPK). There was a subtle drop in CPK down to 8060 U/L, following the introduction of dexamethasone, while conducting further diagnostic studies for neoplasm. Imaging and tumor markers ruled out a solid organ disease and relapse of ovarian cancer. The blood tests reported a negative bone marrow biopsy; however, the results of the skin biopsy and immunochemistry performed on June 9, 2016, were compatible with primary cutaneous conventional variant of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Upon confirmation of the primary cancer, cancer-specific therapy was defined, which started on June 10, 2016, according to the R-CVP protocol (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone).

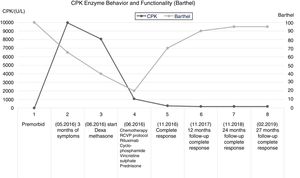

After the initiation of the cancer-specific therapy, the clinical follow-up showed mild improvement in muscle strength of the upper extremities, after the third cycle of chemotherapy. Hence, the patient was able to perform her self-care activities, associated with a marked reduction in CPK one month after the start of chemotherapy (980 U/L). At the time of the fifth cycle of chemotherapy, the CPK values had dropped to 196 U/L. The sixth cycle of R-CVP chemotherapy was administered on October 2016, with complete response according to the assessment on November 18, 2016.

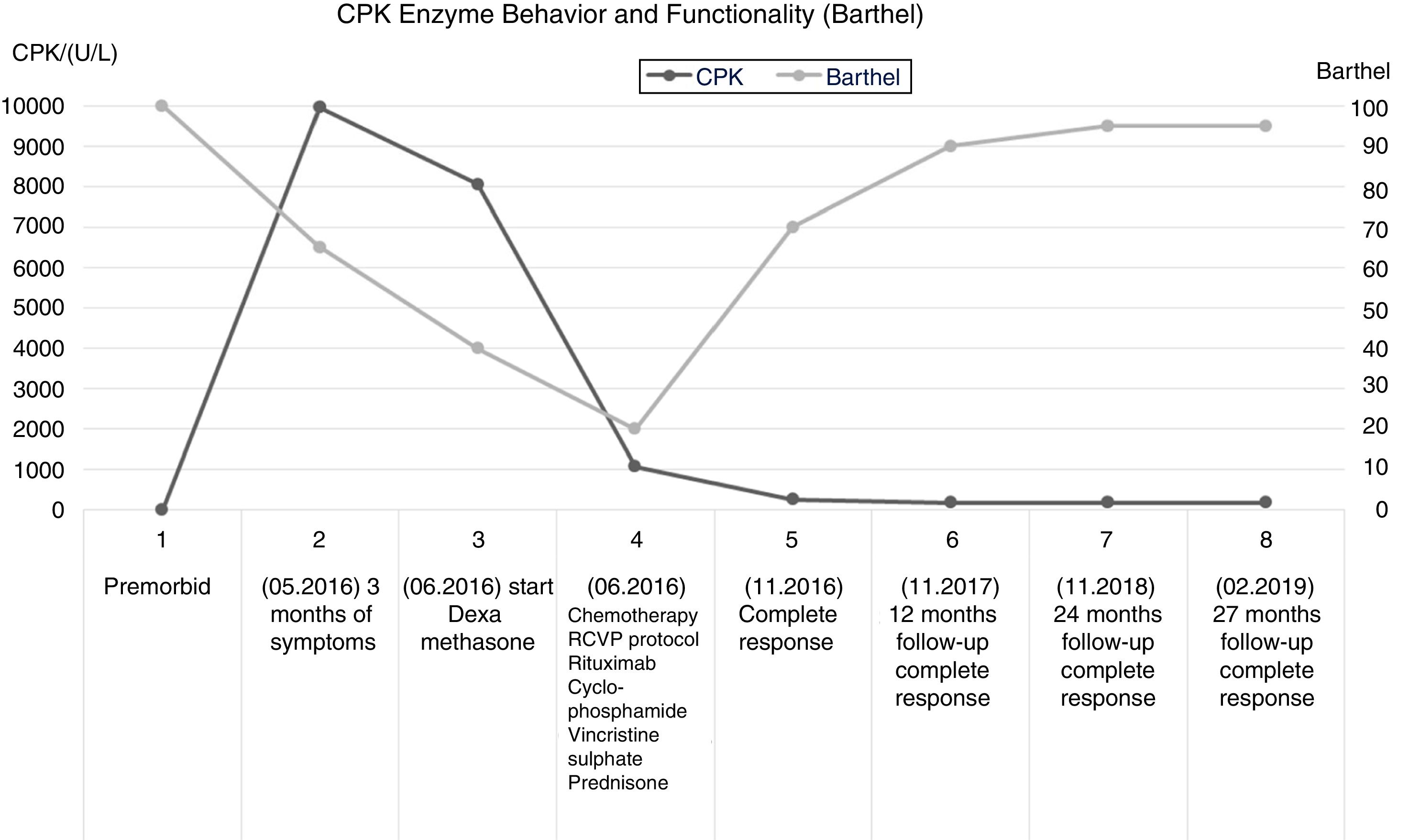

The clinical and paraclinical controls evidenced an inverse relationship between the CPK levels and Barthel global functionality index. The improved performance in the activities of daily living was associated with a progressive gain in muscle strength, up to a 4/5 rating in Daniels scale, both in the proximal and distal segments. This finding gives an indication of the severity of the muscle damage, and the functional impact on the performance of basic activities, in addition to the role of immunomodulation and chemotherapy in myopathic disease. (Fig.1).

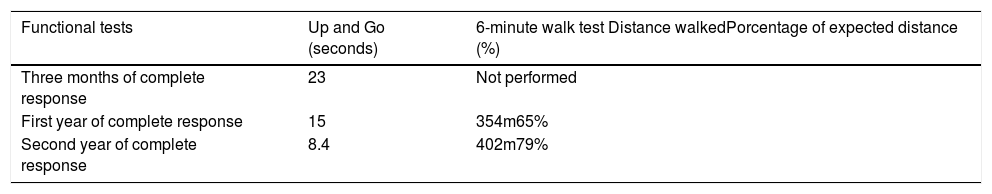

Clinical follow-up was scheduled after 12, 24 and 27 months of complete response; moreover, once the patient was able to walk again, functional tests were conducted using Up and Go and the 6-minute walk, 3 months after complete response, and then at one and 2 years. These tests evidenced an improved motor function, with higher gait efficiency (Table 1). The immunomodulation therapy was maintained with oral steroids and chloroquine for 18 months; over this follow-up period, the patient was in complete remission and maintained her functional independence for the activities of daily living and unassisted gait.

Functional tests, Up and Go test, and 6-minute walk test.

| Functional tests | Up and Go (seconds) | 6-minute walk test Distance walkedPorcentage of expected distance (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Three months of complete response | 23 | Not performed |

| First year of complete response | 15 | 354m65% |

| Second year of complete response | 8.4 | 402m79% |

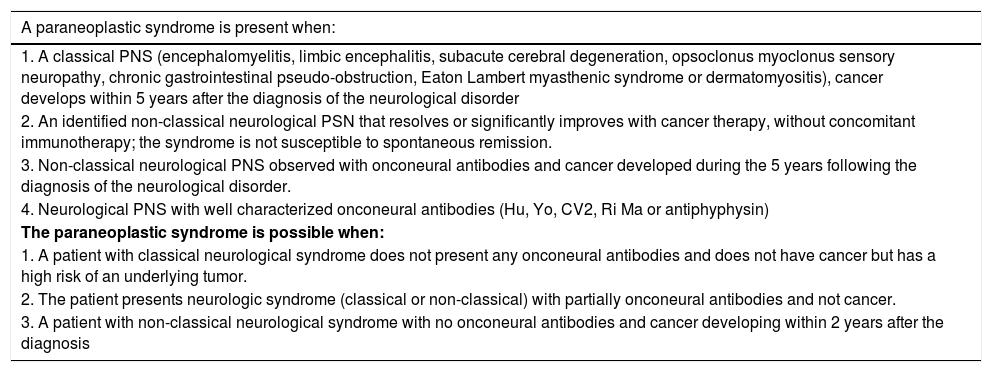

Within the broad spectrum of neuromuscular diseases – which as its name implies involves neuron to muscle impairment,6 consideration should be given to the cancer-associated conditions, particularly neuromuscular PNS. These are functional nervous system disorders, which if not treated promptly, result in permanent structural injury. PNS is associated with tumors of a significant biological activity1,7; their clinical presentation is variable and usually present with rapidly progressive disability.1,3 Therefore, timely diagnosis and treatment are essential to reduce the associated morbidity and mortality. The diagnostic definition of SPN has been developed by the EFNS Task Force 20061 (Table 2). The classification is based on the presence of onconeural antibodies, the clinical manifestations and the response to cancer therapy and immunomodulation with corticosteroids, azathioprine, and immunoglobulin.

Diagnosis of Paraneoplastic syndrome.

| A paraneoplastic syndrome is present when: |

|---|

| 1. A classical PNS (encephalomyelitis, limbic encephalitis, subacute cerebral degeneration, opsoclonus myoclonus sensory neuropathy, chronic gastrointestinal pseudo-obstruction, Eaton Lambert myasthenic syndrome or dermatomyositis), cancer develops within 5 years after the diagnosis of the neurological disorder |

| 2. An identified non-classical neurological PSN that resolves or significantly improves with cancer therapy, without concomitant immunotherapy; the syndrome is not susceptible to spontaneous remission. |

| 3. Non-classical neurological PNS observed with onconeural antibodies and cancer developed during the 5 years following the diagnosis of the neurological disorder. |

| 4. Neurological PNS with well characterized onconeural antibodies (Hu, Yo, CV2, Ri Ma or antiphyphysin) |

| The paraneoplastic syndrome is possible when: |

| 1. A patient with classical neurological syndrome does not present any onconeural antibodies and does not have cancer but has a high risk of an underlying tumor. |

| 2. The patient presents neurologic syndrome (classical or non-classical) with partially onconeural antibodies and not cancer. |

| 3. A patient with non-classical neurological syndrome with no onconeural antibodies and cancer developing within 2 years after the diagnosis |

A 5-year follow-up is recommended for patients without a documented primary tumor, in whom regular testing should be conducted to assess for the presence of malignancy, since after the diagnosis of PNS, many tumors are identified 4–6 months later. The risk of developing cancer significantly decreases after 2 years of the original PNS diagnosis, and is very low after 4 years; however, the clinical variability of these syndromes makes their identification quite difficult.1,2,4,5,7

Given a suspicion of PNS, the symptoms, the age of the patient and the epidemiological profile for cancer, a search strategy should be adopted. In children, the focus should be on hematological malignancies, assessing for splenomegaly or lymphadenopathy; adults on the other hand, should be screened for solid tumors using chest and abdominal x-rays, mammograms, testicular ultrasound, and colonoscopy in people over 50 years old. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET (FDG-PET) scans should be used if the imaging studies are negative, and also when screening for hematolymphoid pathologies. In accordance with the EFNS Task Force 2006 recommendations, if the search is negative, tests should be repeated after 3 and 6 months for one year, and every 6 months for the following 2–4 years; a new search will be conducted in the presence of any alarm symptoms.7

Among the theories intended to explain the genesis of PNS, the immunological theory is the most widely accepted. This theory argues that the tumor expresses antigens – called onconeural antigens – associated with specific types of cancer, with 90% specificity. However, less than 50% of the patients present with onconeural antibodies, only 5-10% develop uncharacterized atypical antibodies, and up to one third of the patients do not express these antibodies. Lymphoma patients may experience PSN in the absence of onconeural antibodies, so this theory fails to account for all the neuromuscular conditions; however, the absence of these antibodies does not rule out malignancy.1,2,7,8

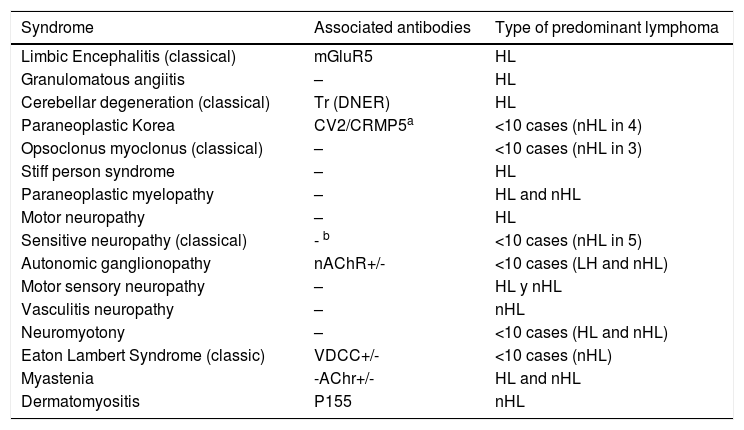

In the presence of lymphoma, neurological PNS develops sporadically.4 According to the European PNS consortium, the association with a specific PNS differs between Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (Table 3). However, the overall incidence of PNS is higher in Hodgkin lymphoma.2 The association with DM is higher in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, whilst polymyositis has been described in both types of lymphoma.2

Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes and type of predominant lymphoma.

| Syndrome | Associated antibodies | Type of predominant lymphoma |

|---|---|---|

| Limbic Encephalitis (classical) | mGluR5 | HL |

| Granulomatous angiitis | – | HL |

| Cerebellar degeneration (classical) | Tr (DNER) | HL |

| Paraneoplastic Korea | CV2/CRMP5a | <10 cases (nHL in 4) |

| Opsoclonus myoclonus (classical) | – | <10 cases (nHL in 3) |

| Stiff person syndrome | – | HL |

| Paraneoplastic myelopathy | – | HL and nHL |

| Motor neuropathy | – | HL |

| Sensitive neuropathy (classical) | - b | <10 cases (nHL in 5) |

| Autonomic ganglionopathy | nAChR+/- | <10 cases (LH and nHL) |

| Motor sensory neuropathy | – | HL y nHL |

| Vasculitis neuropathy | – | nHL |

| Neuromyotony | – | <10 cases (HL and nHL) |

| Eaton Lambert Syndrome (classic) | VDCC+/- | <10 cases (nHL) |

| Myastenia | -AChr+/- | HL and nHL |

| Dermatomyositis | P155 | nHL |

VDCC: voltage dependent calcium channel; HL: Hodgkin lymphoma; nHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; nAChR: nicotinic acetylcholine receptor.

+/-: characteristic of the syndrome; not a cancer predictor.

Adapted from Graus et al.2.

With regards to muscle involvement in lymphoma-associated PNS, this presents in patients over 50 years old, most frequently associated with DM; in up to 50% of the cases, myositis precedes the diagnosis of lymphoid malignancy, in contrast to solid tumor-associated PNS, which presents in advanced stages of cancer.2

DM is an autoimmune myopathy with an incidence ranging between 0.5−0.89 per 100,000/year, and a 2:1female to male ratio. Although it may present at any age, 2 incidence peaks have been described: between 5–15 and 45–65 years.3,4,8 Pure SPN presents in 7-30% of the cases 9 and is diagnosed based on the clinical and paraclinical criteria by Bohan and Peter,5,8,9 shown in Table 4. The clinic is characterized by progressive muscle weakness and skin manifestations. Elevation of enzymes such as CPK is the most sensitive marker to muscle damage.1,3–5,8,9 Findings such as short amplitude and short duration polyphasic motor units, repetitive discharges, positive acute waves and fibrillations during EMG, confirm the intrinsic functional compromise of the muscle fiber. Similarly, the muscle biopsy evidences the structural damage and mononuclear infiltration, contributing with valuable information for the discussion about differential diagnoses. Both studies need to do a proper selection of the muscle to be assessed, in addition to a correct interpretation. However, the specific onconeural antibodies present in this condition have not yet been described.7

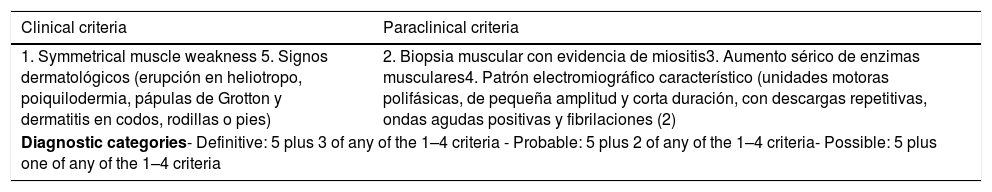

Bohan and Peter criteria.

| Clinical criteria | Paraclinical criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Symmetrical muscle weakness 5. Signos dermatológicos (erupción en heliotropo, poiquilodermia, pápulas de Grotton y dermatitis en codos, rodillas o pies) | 2. Biopsia muscular con evidencia de miositis3. Aumento sérico de enzimas musculares4. Patrón electromiográfico característico (unidades motoras polifásicas, de pequeña amplitud y corta duración, con descargas repetitivas, ondas agudas positivas y fibrilaciones (2) |

| Diagnostic categories- Definitive: 5 plus 3 of any of the 1–4 criteria - Probable: 5 plus 2 of any of the 1–4 criteria- Possible: 5 plus one of any of the 1–4 criteria | |

The first case of stomach cancer-associated DM was reported by Stertz in 1916.4 The incidence rate of tumors in patients with DM varies from 0.6 to 10 per 100.000 people.8 The Souza & Shinjo trial found that of 139 patients with DM, 8.6% were diagnosed with cancer in the first year,10 while Zhang et al. reported in their trial that out of 678 cases of DM followed over 34 years, 115 (17%) cases of malignancies were reported.11 When a diagnosis of DM is made, a screening for malignancy should follow, due to the increased morbidity and higher risk of mortality. The following are risk factors to suspect the association between DM and cancer: advanced age, male, dysphagia, cutaneous vasculitis, skin necrosis, accelerated progression of the disease.4,10,11 The malignancies most commonly associated with DM are ovarian and breast cancer in women, and lung cancer in men.4,9 Nevertheless, the association with a particular type of tumor is variable; for instance, Zhang et al. reported nasopharyngeal carcinoma as the most frequent presentation (51.3%), which relates to the epidemiological profile of this group, based on the high incidence of this malignancy in the Asian population.11 Malignant skin tumors are also associated with connective tissue autoimmune disease, including DM and polymyositis.4

DM may present before (40%), concurrently (26%) or after (34%) the diagnosis of cancer.1,3,4 Within the next 5 years after the diagnosis, there is a high risk of developing ovarian, pancreatic and lung cancer; the risk of lymphoma is high only during the first year after the DM diagnosis; in the case of other tumors, the risk is higher during the first year of follow-up, and then is significantly reduced.7

The therapeutic approach for PNS focuses on immunomodulation with corticosteroids and azathioprine, and the study of the malignant neoplasm to initiate timely cancer therapy1,5,7; the use of intravenous immunoglobulins and plasmapheresis has shown favorable clinical results in a small number of cases.1 Approximately 30% of the patients are permanently disabled.8 Age, the severity of the muscle disease and associated systemic involvement, and the rapid response to corticosteroids, are considered functional prognostic factors in patients with DM.9

Considering the history of ovarian cancer in our patient, and the presence of cutaneous lymphoma, a literature search was conducted about the frequency of PNS in second primary tumors. Both synchronous and metachronous secondary malignancies were reported. Sakai et al. reported a case of DM in metachronous cancer of the contralateral breast when reviewing 20 cases of DM-associated breast cancer in an Asian population.12 Voravud et al. reported 6 cases of DM-associated breast cancer, and in 2 of them primary ovarian cancer was confirmed as a second neoplasm. They argued that any DM developing during the course of breast cancer, may lead to a second malignant primary neoplasm or recurrent breast cancer.13 Notwithstanding the fact that dual malignancy is seldom associated with PNS, Nasri et al. in 2016 summarized the case reports on dual malignancy and PNS, excluding DM, or cases of PNS and lymphoma.14 They found one case of a patient with 3 primary malignancies of bilateral metachronous breast cancer and during the course of the DM, that confirmed the coexistence with endometrial carcinoma. The authors further argue that the presence of DM in the context of multiple malignancies is rare.15 There were no cases of paraneoplastic DM in the context of lymphoma or ovarian cancer.

In the clinical case herein discussed, the patient met the clinical criteria for a final diagnosis of DM, based on the marked CPK elevation, and on the electromyographic and clinical findings. No muscle fiber biopsy was performed because of the clinical condition of the patient. This is a classical PNS case where the destruction of muscle fiber could be reduced using immunomodulation therapy and progressive motor and functional recovery achieved as a result of cancer specific treatment. After full recovery from her cancer, the patient continued to improve until she became functionally independent; this improvement has been maintained over the 2 years of follow-up (Fig. 1). There were favorable prognostic factors derived from the timely diagnosis of the PNS and of the hematolymphoid malignancy, which allowed for a timely administration of immunomodulation and systemic therapy, mitigating the muscle loss and driving functional recovery; however, the performance in the 6-minute walk test – notwithstanding the improvement during the clinical follow-up – is still below the expected level of performance.

ConclusionSuspecting a neurological PNS requires an active screening for malignancy. This case describes a paraneoplastic DM as the initial presentation of a cutaneous lymphoma. No muscle biopsy or onconeural antibodies were performed, However, this is a classical PNS case that should be assessed clinically and electro-physiologically by experienced cancer specialists. The level of muscle fiber destruction is associated with the biological activity of cancer and causes further morbidity and disability; although the response to steroids may be considered a good prognostic factor, the key to treating this patient is the cancer specific treatment.

FinancingNone.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to disclose with regards to the information presented in this clinical case.

We want to acknowledge Miguel Moreno Capacho, medical doctor specialized in Physical Medicine and rehabilitation; physiatrist, cancer specialist; head of the Rehabilitation Department at the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología E.S.E., Bogotá, D.C. Colombia, for his contribution in reviewing this paper.

Please cite this article as: Moya ÁS, Castro SB, Rivera AH. Dermatomiositis paraneoplásica como presentación de linfoma. Reporte de caso y revisión de la literatura. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2020;27:224–229.