Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic disease of unknown cause, secondary to a genetically determined immune reaction triggered by environmental factors, which leads to the formation of non-caseating granulomas. Ocular involvement is the second most frequent after pulmonary involvement. The most common finding is anterior granulomatous uveitis, but posterior uveitis, retinal peri-phlebitis, chorioretinitis, conjunctivitis, scleritis and optic neuritis can also be seen. We describe the case of a pediatric patient with long-standing multisystem involvement disease, in whom the demonstration of non-caseating granulomas in the conjunctival biopsy allowed a presumptive diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

La sarcoidosis es una enfermedad multisistémica de causa desconocida, secundaria a una reacción inmunitaria determinada genéticamente y desencadenada por factores ambientales, que conlleva la formación de granulomas no caseosos. El compromiso ocular es el segundo más frecuente después del pulmonar. El hallazgo más común es la uveítis granulomatosa anterior, también se puede evidenciar uveítis posterior, periflebitis retiniana, coriorretinitis, conjuntivitis, escleritis y neuritis óptica. Describimos el caso de una paciente pediátrica con una enfermedad de compromiso multisistémico de larga data, en quien la demostración de granulomas no caseificantes en la biopsia conjuntival permitió establecer el diagnóstico presuntivo de sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease of unknown cause, apparently secondary to a genetically determined immune reaction triggered by environmental factors, which entails the formation of non-caseating granulomas in any tissue, mainly in the lungs, intrathoracic lymph nodes, skin, parotid glands and eyes.1 According to various studies, the prevalence is higher in adults than in children and predominates in the African-American race and in women.2–4

After lung affectation, ocular involvement is the second most frequent5,6; it occurs in approximately 30–60%7,8 of cases. It can be the first manifestation in up to 20%9 of patients. The most frequent finding is granulomatous anterior uveitis; however, posterior uveitis, retinal periphlebitis, chorioretinitis,10 conjunctivitis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, scleritis and optic neuritis can also be evidenced, which sets up a diagnostic challenge due to the multiple entities that can occur with these findings, such as tuberculosis, syphilis and intraocular lymphoma.11

In the conjunctiva, the most typical manifestation is the presence of nodules, which appear in 7 to 17% of ocular sarcoidosis.12 Clinically, it is seen as yellowish nodules of variable size that can be located in the inferior conjunctival fornix or in the posterior surface of the lower eyelid.1 Below, we present the clinical case of a pediatric patient whose conjunctival biopsy played a very important role in the diagnosis and subsequent management.

Clinical caseIt is a 10-year-old female patient, of mixed race, with a history of atrial septal defect with secondary lung hypertension that required surgical correction, who was admitted to a high-complexity hospital due to a clinical picture that began at three years of age, consisting of bronchoobstructive syndrome and recurrent respiratory infections, associated with chronic diarrhea and pondostatural delay.

The first studies performed were a chest X-ray and CT scan, with diffuse parenchymal involvement and bilateral multiple prevascular, pretracheal and subcarinal lymphadenopathies in the aortopulmonary window, and hilar; tuberculin: 0 mm; bronchoalveolar lavage with lymphocyte cellularity with no evidence or fungal infections or mycobacteria; and fecal elastase within normal ranges.

Initially, cystic fibrosis was suspected, but with negative quantitative iontophoresis, non-compatible tomographic findings, without pancreatic insufficiency, and extended genetic studies which included a trio exome, which rules out this condition (CFTR without pathogenic mutations), but reports mutation causative of immunodeficiency 32B (Table 1).

Report of results of diagnostic aids performed.

| Date | Diagnostic aids | Result |

|---|---|---|

| February 2015 | HRCT chest scan | Mosaic attenuation pattern, bronchiectasis of the anterior segment of the right upper lobe, lingula and left lower lobe, non-specific randomly distributed micronodules |

| April 2015 | Iontophoresis | 37 mmol/NaCl |

| May 2015 | Purified Protein Derivative Skin Test (tuberculin) | 0 mm |

| February 2018 | Iontophoresis by electrical conductivity | 104 mmol/l |

| March 2018 | Next generation sequencing of CFTR gene | Negative for pathogenic mutations |

| April 2018 | Iontophoresis | 84 mmol/NaCl |

| October 2018 | Trio exome (GenCell) | Compound heterozygous mutation in the IRF8 gene c.602C > T; p.Ala201Val splicing mutation/c.1169_1170delTG; p.Val390Aspfs*79, causative of immunodeficiency 32B; no pathogenic mutations in the CFTR gene were identified |

| November 2018 | Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage | Negative Gram, bacilloscopies, aerobic cultures, KOH, Indian ink, and fungal and mycobacterial cultures |

| December 2018 | Lymphocyte subpopulations (bronchoalveolar lavage) | Total lymphocytes 26.9%Monocytes CD45/CD14 10/5CD4/CD8 ratio 2/9 |

| January 2019 | Chest CT scan with contrast | Multiple bilateral, hypodense, heterogeneous perivascular, peritracheal, subcarinal, in the aortopulmonary window and hilar lymphadenopathies without calcifications or necrosis; both lungs with a ground-glass pattern of patchy distribution, partially involving the upper lobes bilaterally and asymmetrically and to a lesser extent the lower lobes. Marked diffuse thickening of the peribronchovascular interstitium with thickening of inter and intralobular septa |

| Pancreatic elastase in stools | >500 µg/g | |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme | 85.8 U/l | |

| HIV | Non-reactive | |

| AgSHB | Non-reactive | |

| March 2019 | Protein electrophoresis | Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia |

| IgG antirubella | 48.92 | |

| July 2019 | Right lung biopsy | Interstitial lymphoid infiltrate with presence of poorly formed granulomas |

| Upper GI endoscopy | Active duodenitis, intestinal lymphangiectasia | |

| October 2019 | Immunoglobulins | IgE 6.58 mg/dlIgG 5194.3 mg/dlIgM 162.1 mg/dlIgA 53 mg/dl |

| March 2020 | 25-hydroxyvitamin D | 11.8 ng/mL |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin | 0.42 µmol/l | |

| Albumin | 3.3 g/dl | |

| December 2020 | ANA | 1:320, speckled pattern, HELLP cells substrate |

| Protein electrophoresis | Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia | |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme | 84.8 U/l | |

| 24 h urine calcium | 31 mg/24 h | |

| January 2021 | ENA | Negative |

| Upper GI endoscopy | Nodular esophagus, erythematous retropyloric fold, duodenum with appearance indicative of lymphangiectasia Biopsy: within normal limits | |

| Colonoscopy | Ileal nodular hyperplasia, erythema in the cecum Biopsy: macrophages in lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate, without granuloma formation | |

| Ultrasound of soft tissues of the neck | Nodular lesion in the right supraclavicular region (station iv), not palpable. Parotid glands of heterogeneous appearance with multiple intraparenchymal hypoechoic areas consistent with probable sialectasis | |

| Salivary gland biopsy | Within normal limits | |

| Biopsy of the nasal superior bulbar conjunctiva, right and left eyes | Chronic granulomatous conjunctivitis |

Given the presence of multiple mediastinal lymphadenopathies and pathological alterations of the lung parenchyma, without a clear diagnosis, the patient was assessed by a multidisciplinary team, which decided to perform lung and gastrointestinal biopsies in order to rule-out granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis.

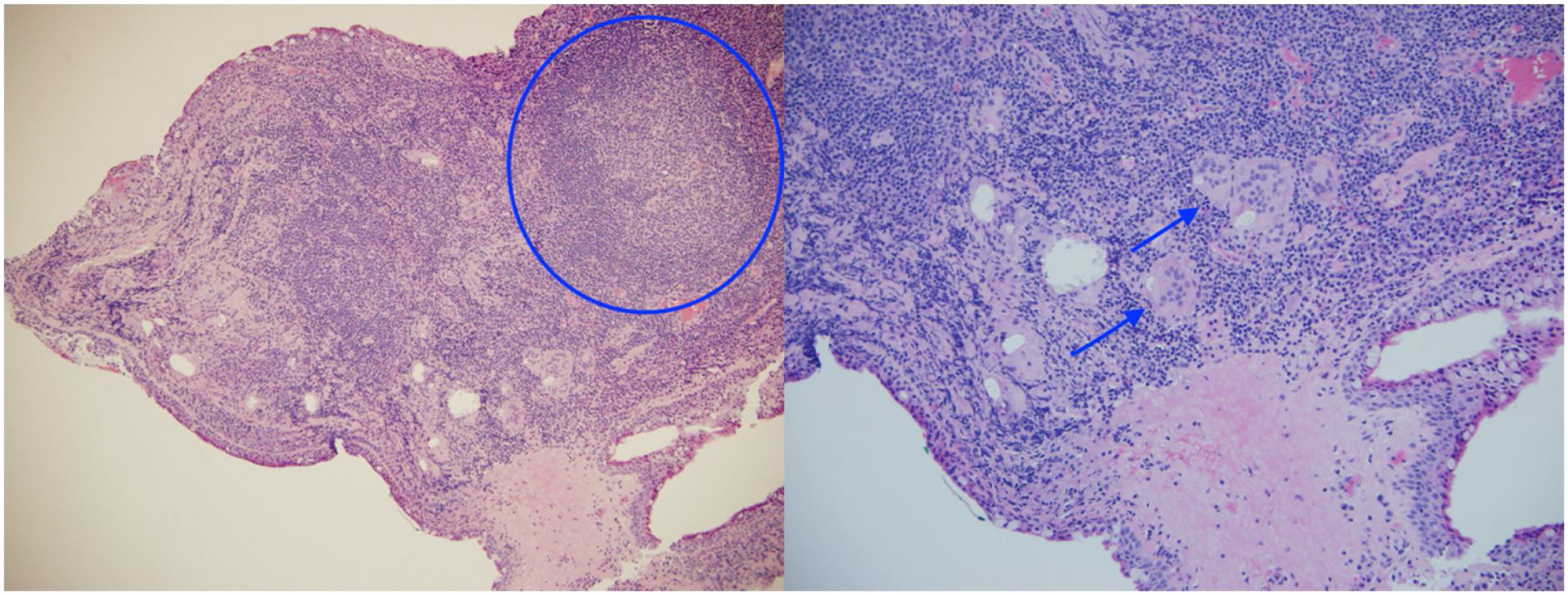

Likewise, a video-assisted right lung biopsy was performed, with findings that point to interstitial lymphoid infiltrate with the presence of poorly formed granulomas, as well as endoscopic studies that revealed flattening of the villi and significant lymphoplasmacytic infiltration.

During the study, her older sister was diagnosed with sarcoidosis; the difference was that the latter presented hypertrophy of the parotid glands, xerostomia, polyarthralgia without arthritis and gastrointestinal symptoms, the latter being infrequent in sarcoidosis, which is why rheumatology did not rule out the presence of immunodeficiency or Sjögren's syndrome as a primary disease.

New paraclinical tests were performed, with the result of elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme, protein electrophoresis with polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (IgG predominance), calciuria within the normal range, low 25-hydroxyvitamin D, positive antinuclear antibodies, negative extractable nuclear antigens and parotid gland biopsy without foci of mononuclear infiltrate, atrophy, fibrosis, amyloid deposition (with routine staining and Congo Red stain) or granulomas (Table 1).

Due to the worsening of her respiratory symptoms, the patient was admitted again to the emergency department, and for this reason, rheumatology decided to start urgent immunosuppression with prednisolone and azathioprine at doses of 1 mg/kg and 1.15 mg/kg, respectively, and requested evaluation by ophthalmology in order to evaluate findings compatible with ocular sarcoidosis.

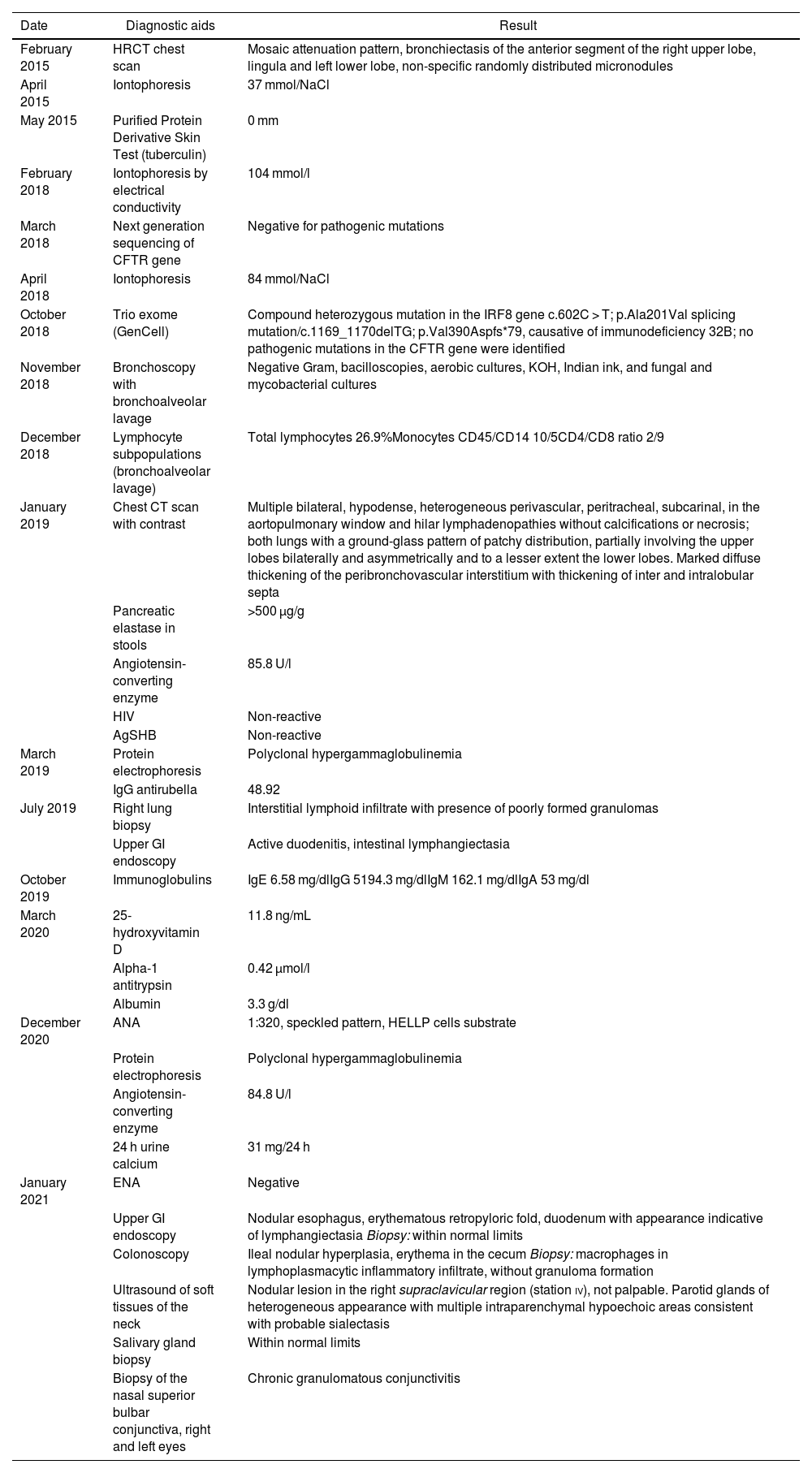

The ophthalmological examination revealed a visual acuity of 20/25 in both eyes and micronodules in the nasal superior bulbar conjunctiva at 7 mm from the limbus in both eyes (Fig. 1), in addition to a remnant of the pupillary membrane. No cells, keratic precipitates, flares or synechiae were found in the anterior chamber. Under pharmacological dilation, vitreitis was not observed, and the nerve and the macula were found healthy. No vascular abnormalities, mid-periphery or lesions were detected. Given the absence of a confirmed diagnosis, it was decided to take a conjunctival biopsy, which reported chronic granulomatous conjunctivitis with non-necrotizing and non-suppurative granulomas (Fig. 2).

Although the pulmonary histopathological findings were not conclusive for sarcoidosis, the clinical syndrome, the evidence of non-caseating granulomas on the conjunctival biopsy, the high levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme, the early-onset hypergammaglobulinemia and the family history of an older sister diagnosed with sarcoidosis led to the presumptive diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

Until the present day, the patient continues under multidisciplinary follow-up by pediatric pulmonology, genetics, rheumatology, gastroenterology and ophthalmology. After 10 months of immunosuppressive treatment associated with human gamma globulin, she has had a satisfactory evolution; she has no vasculitic lesions, cervical lymphadenopathy or parotid enlargement; she has only presented a pulmonary exacerbation due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, without requiring hospital readmissions. As for ophthalmology, she continues without intraocular involvement, without new lesions on the ocular surface and without any type of topical treatment.

Due to the atypical manifestations already mentioned, the genetic study of her sister and parents is in process of being evaluated in order to compare possible genetic variants that could explain the similarity of the clinical picture in both patients.

DiscussionThe diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis is an important challenge for medicine, especially in the field of pediatrics, since there are no specific tests for this condition, but rather the sum of various aspects that include clinical manifestations, biochemical tests, findings in diagnostic images and histopathological studies is required.13

We present the clinical case of a female school-age patient with complex primary disease that began with pulmonary and gastrointestinal involvement already described, in whom it was possible to rule out cystic fibrosis and other granulomatous diseases, such as tuberculosis, syphilis, and fungal or mycobacterial infections

During the study, the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms (uncommon in the aforementioned disease) and the non-conclusive findings on the lung biopsy made the early recognition of sarcoidosis difficult, however, the tomographic findings associated with biomarkers (elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme, hypergammaglobulinemia and negative tuberculin skin test in an individual who resides in a tuberculosis-endemic area, evidencing anergy associated with sarcoidosis), and especially the histopathological result of the conjunctival biopsy which confirmed the presence of non-necrotizing granulomas, raised the probable diagnosis of the disease in question.

In the pediatric population, the involvement in sarcoidosis is more of extrapulmonary type, with ocular, cutaneous and rheumatological manifestations,14 as is the case of the patient. The most frequent intraocular lesions are uveitis, manifested as iritis, retinal perivasculitis, and nodules in the trabeculum,15 and it is also common to find involvement of the ocular surface, mainly in the conjunctiva and the lacrimal gland. It should be taken into account that the visual impact can become severe, leading to the development of blindness, which is usually explained by cystoid macular edema.16

On many occasions, there is no specific ocular symptomatology in childhood. This is where the exhaustive search for signs in the ophthalmological examination can provide the necessary information to establish a diagnosis. It is important to carry out a correct assessment of the ocular surface, including the exposure of the bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva, in which conjunctival lesions hidden by the eyelids can be seen. Conjunctival involvement can be observed in 6% to 40% of patients with sarcoidosis, mainly as a nodular lesion,17 usually asymptomatic. These conjunctival lesions gain importance because they are an easily accessible site for histopathological study, which turns out to be a very attractive option for the different anatomopathological studies to confirm the sarcoidosis,18 with a diagnostic performance that can range from 24% to 75%.19–21

Conjunctival biopsy is considered a safe procedure, simpler and less expensive than other histopathological studies. Patients with a positive conjunctival biopsy could save a total of approximately 17 procedures, with a cost for the year 2012 of around USD$843, compared to USD$1774 for a transbronchial biopsy and USD$5447 for a mediastinoscopy with biopsy.22 Therefore, from a cost-effectiveness analysis, conjunctival biopsy could be considered as one of the first sites for histopathological sample collection in patients with suspected sarcoidosis.

Currently, sarcoidosis continues to be a diagnostic challenge, since due to its variety of presentation and multisystem involvement it can simulate different diseases, which is why it is usually considered a diagnosis of exclusion. Conjunctival biopsy should be classified as a first-line study, due to its easy access, less invasiveness, lower morbidity22 and significant diagnostic performance when there is a clinical suspicion of up to 75%.21 For this reason, it is of great help in complex cases in which the diagnosis is not very clear and tissue studies are required to define the entity.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that, prior to the development of this research, informed consent was obtained from the legal representative of the patient; that the research complies with the current regulations on bioethical research; that approval was obtained from the medical ethics committee of the Pablo Tobón Uribe Hospital; and that this article does not contain data, personal information or images that would allow to identify the patient.

FundingThe authors declare that they have not received any type of funding or grants for the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and have not received money from any institution. The Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe offered the research group all the logistical support necessary to carry out the data collection, analysis and preparation of the research article.