In the follow-up of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients, the physical examination of the joints in order to determine the number of painful and swollen joints is the cornerstone for determining activity. The objective of this study was to find out the opinion of a group of rheumatologists as regards the examination of joints of patients with RA to define the swollen or painful joint. At the same time an evaluation was made on the variation in the joints examination between the participants.

MethodsA questionnaire was administered to a group of rheumatologists in order to determine general issues and examining each of the joints, as well as concepts of definitions of pain and inflammation in the joints.

ResultsThe majority of the participants (78%) stated that all aspects were important, such as evaluating passive joint mobilisation, pain to palpation, and spontaneous pain. Passive mobility without having pain or swollen joint tenderness was said to be important by 53.8% of the participants, and 62.6% agreed with observing the pressure exerted by the examiner until the nail bed of the finger started to turn pale. As regards touching the margin of joint to determine swelling, 55% agreed, and 14.3% were not sure. Synovial effusion, fluctuation, and the alteration in the range of motion to define inflammation in the examination of joint were important for 47.2% of the examiners. Almost three-quarters agreed with the temporomandibular, acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular, shoulder and ankle joint technique. It was obvious that few were in accordance with the technique in the hip joint. When asked about more than one technique in some joints such as the MCF (57.1%) and mid tarsal (45%) joints, there was a decrease in the percentage of those who agreed with one of the 2 techniques.

DiscussionApparently, there is no standard joint assessment method, since there were different opinions in the techniques proposed. This could be critical since examination of joints is the basis of the clinimetric examination in RA. A significant percentage of the group did not agree or were unsure of some components of the examination. This could lead to a variation in the concepts and a misclassification of patients in order to determine the activity of RA. This would also have an impact on the T2T or treat to target strategy.

ConclusionThere was a wide variation in opinions about the concepts related to the examination of joints, such as defining swollen or painful joints in patients suffering RA. This requires a process of standardisation as the best recommended alternative.

En el seguimiento de los pacientes con artritis reumatoide (AR) el examen articular (determinar el número de articulaciones dolorosas e inflamadas) es la piedra angular para determinar la actividad. El objetivo del estudio fue conocer la opinión de un grupo de reumatólogos acerca del examen articular de los pacientes con AR al definir la articulación tumefacta o dolorosa y, de la misma manera, evaluar la variación en el examen articular entre los participantes.

MétodosSe aplicó un cuestionario, desarrollado por los autores, a un grupo de reumatólogos para explorar aspectos generales y específicos al examinar cada una de las articulaciones, además de conceptos de las definiciones de dolor y de inflamación en el examen físico.

ResultadosEl 78% de los entrevistados consideró que todos los aspectos eran importantes, como evaluar la movilización pasiva de la articulación, explorar el dolor a la palpación y el dolor espontáneo. El 53,8% consideró la movilidad pasiva sin que haya dolor o edema articular a la palpación. El 62,6% estaba de acuerdo con realizar la presión hasta cuando comienza a palidecer el lecho ungular del dedo del examinador. En el momento de palpar el margen articular para determinar la inflamación, el 55% estuvo de acuerdo y el 14,3% no estuvo seguro. Para el 47,2% eran importantes el derrame articular, la fluctuación y la alteración del rango del movimiento para definir la inflamación en el examen articular. Cerca de las tres cuartas partes estuvo de acuerdo con la técnica de las articulaciones temporomandibular, acromioclavicular, esternoclavicular, hombro y tobillo. Se evidenció que pocos estaban de acuerdo con la técnica en la articulación de la cadera. Al preguntarse por más de una técnica en algunas articulaciones, como las MCF (57,1%) y del tarso medio (45%), el porcentaje de los que estuvieron de acuerdo con una de las 2 técnicas disminuyó.

DiscusiónAl parecer no existe un método de examen formal, ya que hubo diferentes opiniones en las técnicas propuestas. Esto puede ser crítico, ya que el examen articular es la base de la clinimetría de la AR. Un porcentaje importante del grupo no estuvo de acuerdo o seguro acerca de algunos conceptos sobre componentes del examen, lo que denota una variación en los conceptos y esto podría llevar a la mala clasificación de los pacientes al determinar la actividad de la enfermedad, lo que impactaría en la estrategia T2T o treat to target.

ConclusiónExistió una gran variación en la opinión acerca de los conceptos relacionados con el examen articular del paciente que padece AR al definir articulaciones tumefactas o dolorosas, por lo que se recomienda a futuro un proceso de estandarización como la mejor alternativa.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic and multifactorial autoimmune disease, characterized by joint inflammation and pain that result in limitation of motion, impaired functionality and increased risk of death associated with extra-articular manifestations.1 Joint count (determining the number of painful and swollen joints) is the cornerstone for establishing the activity of the disease and classifying its severity when following patients with RA. Joint count is a key component of the various rating scales; however, it is a very variable measurement with poor reproducibility.2–4 It has been said that proper training of patients allows them to identify the swollen joints with an acceptable correlation as compared to the assessment of an expert rheumatologist.5 Nevertheless, there is no clearly defined technique to conduct the joint examination to determine the activity of the disease; and one of the major issues with joint count in RA clinimetrics is the variation among clinicians, and even among rheumatologists, both in terms of the osteomuscular examination, and in terms of the general examination of the patient. Consequently, this affects the total scores of the various scales used to define disease activity in practice.6,7

The purpose of the study was to learn about the opinion of a group of rheumatologists with regards to the technique used for the joint examination of patients with RA, when identifying swollen or tender joints; and, to learn about the variation in the clinical assessment of the joints among the participants.

MethodsA questionnaire was designed to explore three areas of interest: general aspects, assessment of pain and swelling, particular aspects of the definitions related to the examination of the joints and the exploration of each of the joints included in the clinemetric indexes to determine which joints were swollen or tender, based on the official manual of the European League Against Rheumatism for the clinical assessment of RA.8

The survey items were developed based on a previous discussion on the topic with the participation of a group of rheumatologists, based on the articles from the systematic review,7 and on the book of the European League Against Rheumatism.8 Closed and open questions were asked to further explore the topic, if the interviewees agreed. The questionnaire was self-administered and submitted in hard copy; it was 7 pages long. The 92 rheumatologists participating in the General Assembly of the Colombian Association of Rheumatology held during the Colombian Congress of Rheumatology in Bucaramanga in 2018, were asked to complete the survey. The questionnaire comprised 30 questions distributed into 4 topics and general questions: Questions 1–3, about joint pain during the examination of the activity of the disease; Questions 4–5, about joint swelling; Questions 7–10, about the general examination; Questions 11–27, about the examination of each individual joint; and 20–30, general questions. The questions and answers were submitted based on multiple choice categorical variables and the number of questions varied in accordance to the topic of interest. A pilot test was conducted with 5 rheumatologists to refine the questions, the topics, and correct any potential wording issues. The participants were asked to write their names to make sure that all of the surveys were accounted for, but the information was confidential. No demographic questions were asked, and no incentives were offered. Accepting to complete the survey was considered an informed consent, and since there were no sensitive issues or interventions involved, the protocol was not submitted to an ethics committee.

ResultsThe participating rheumatologists (92) came from all over the country and represented the majority of the membership of the Association (165 members). 99% (91) of the participants in the conference completed the entire survey (there were some questionnaires where up to 8.8% of the questions were not answered, but were considered totally completed). Most of the respondents – when answering the general questions – agreed that a consensus was needed (86.8%). Forty seven of 91 (51%) said that there is not enough literature on the topic and 34% believed it was just the opposite; 11% were not sure and 3% did not answer. There were no answers to the question about whether any of the examination techniques was left out.

With regards to the questions about the assessment of joint pain, 78% considered that all of these topics were relevant, for instance assessing the passive motion of the joint, exploring pain at palpation, in addition to spontaneous pain; 13% considered than only palpation was important. When asked whether passive mobility should be assessed in the absence of pain or joint edema, about one half of them (53.8) agreed and 16% disagreed. 62.6% agreed with using pressure until the nail bed of the examiner turns pale (the thumb technique); 27.5% disagreed and 8.8% were not sure.

With regards to the section on assessment of joint swelling, the question about whether the joint margin should be palpated to identify swelling, 55% agreed, 26.4% disagreed and 14.3% were not sure. When asked about including this in the definition of joint swelling, edema or tumefaction, 47.2% considered important the options about the presence of joint effusion, fluctuation at palpation and range of motion alteration, but with no joint deformity. Nobody agreed with the statement that there is swelling when there is range of motion alteration in the absence of deformity. 22% agreed with all the options. For the question about the determination of joint swelling accompanied by a deformity, 2.2% agreed on including also soft tissue swelling; 5.5% joint effusion, 6.6% range of motion alterations, 20.9% all of the above, and 11% none.

With regards to the general joint examination section, 54% disagreed with first exploring the swelling of each individual joint, and then pain, to avoid examiner bias; 35.2% agreed. In terms of the preference of the examiner for the patient’s positioning for examination, 83.5% preferred having the patient sitting down to examine the upper body and then laying down to examine the lower body; 8.8% preferred lying down throughout the examination and 7.7% mentioned a different option, were not sure, or did not answer. Regarding the sequence of the examination, 36.3% preferred to examine the patient from head to toe; 19.8% alternating by regions; 3.3% first one side of the body and then the other side; and 16.5% preferred head to toe and alternating. When asked if a joint with prosthesis, trauma or recent surgery with pain should be excluded from the joint count, 82.4% agreed, 11% disagreed and 5.5% were not sure.

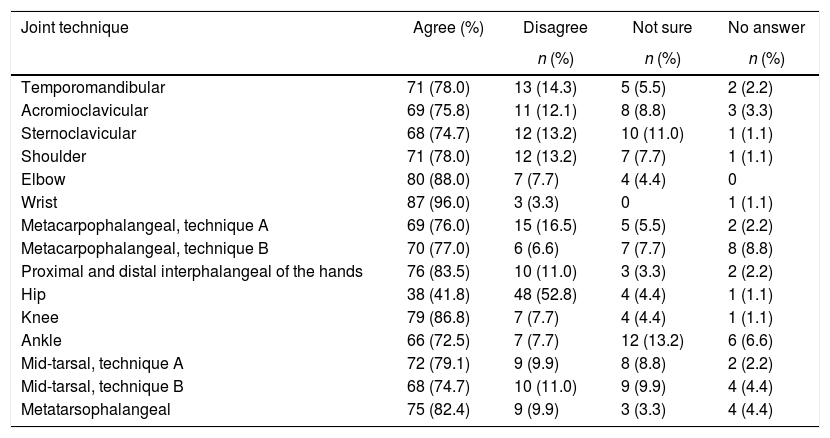

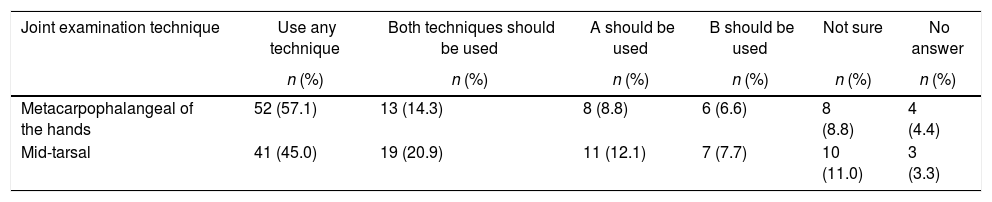

Regarding the question about the examination technique for each joint, the results showed different techniques for the different joints (Table 1) and also when 2 techniques for the same joint were considered (Tables 2 and 3).

Results on the use of one single technique for each joint (n = 91).

| Joint technique | Agree (%) | Disagree | Not sure | No answer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Temporomandibular | 71 (78.0) | 13 (14.3) | 5 (5.5) | 2 (2.2) |

| Acromioclavicular | 69 (75.8) | 11 (12.1) | 8 (8.8) | 3 (3.3) |

| Sternoclavicular | 68 (74.7) | 12 (13.2) | 10 (11.0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Shoulder | 71 (78.0) | 12 (13.2) | 7 (7.7) | 1 (1.1) |

| Elbow | 80 (88.0) | 7 (7.7) | 4 (4.4) | 0 |

| Wrist | 87 (96.0) | 3 (3.3) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Metacarpophalangeal, technique A | 69 (76.0) | 15 (16.5) | 5 (5.5) | 2 (2.2) |

| Metacarpophalangeal, technique B | 70 (77.0) | 6 (6.6) | 7 (7.7) | 8 (8.8) |

| Proximal and distal interphalangeal of the hands | 76 (83.5) | 10 (11.0) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (2.2) |

| Hip | 38 (41.8) | 48 (52.8) | 4 (4.4) | 1 (1.1) |

| Knee | 79 (86.8) | 7 (7.7) | 4 (4.4) | 1 (1.1) |

| Ankle | 66 (72.5) | 7 (7.7) | 12 (13.2) | 6 (6.6) |

| Mid-tarsal, technique A | 72 (79.1) | 9 (9.9) | 8 (8.8) | 2 (2.2) |

| Mid-tarsal, technique B | 68 (74.7) | 10 (11.0) | 9 (9.9) | 4 (4.4) |

| Metatarsophalangeal | 75 (82.4) | 9 (9.9) | 3 (3.3) | 4 (4.4) |

Results of the evaluation of using the 2 existing techniques on the same joint (n = 91).

| Joint examination technique | Use any technique | Both techniques should be used | A should be used | B should be used | Not sure | No answer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Metacarpophalangeal of the hands | 52 (57.1) | 13 (14.3) | 8 (8.8) | 6 (6.6) | 8 (8.8) | 4 (4.4) |

| Mid-tarsal | 41 (45.0) | 19 (20.9) | 11 (12.1) | 7 (7.7) | 10 (11.0) | 3 (3.3) |

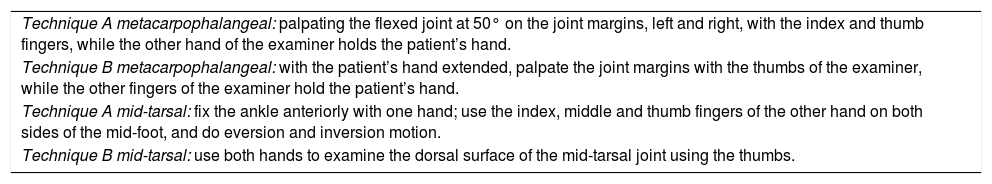

Description of the A and B techniques in metacarpophalangeal and mid-tarsal.

| Technique A metacarpophalangeal: palpating the flexed joint at 50° on the joint margins, left and right, with the index and thumb fingers, while the other hand of the examiner holds the patient’s hand. |

| Technique B metacarpophalangeal: with the patient’s hand extended, palpate the joint margins with the thumbs of the examiner, while the other fingers of the examiner hold the patient’s hand. |

| Technique A mid-tarsal: fix the ankle anteriorly with one hand; use the index, middle and thumb fingers of the other hand on both sides of the mid-foot, and do eversion and inversion motion. |

| Technique B mid-tarsal: use both hands to examine the dorsal surface of the mid-tarsal joint using the thumbs. |

There was more agreement about the techniques for the wrist, elbow, knee, interphalangeal of the hands and metatarsophalangeal. Less agreement was found with regards to the technique to approach the TMJ, and the acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular, shoulder and ankle joints. The lowest level of agreement was regarding the technique to assess the hip. When asked about 2 techniques for the same joint, there were contradictory opinions and more than one half (57; 62.6%) of the rheumatologists said that either technique could be used (Table 3) for the metacarpophalangeal hand joints and less than one half (45; 49.4%) for the mid-tarsal joint. Around 10% of the respondents were not sure when considering both techniques.

DiscussionNotwithstanding the importance of the joint examination to establish the activity of the disease in RA, based on a systematic literature review on the topic, there are no articles in the literature describing each technique in detail.7 This may be partly due to the assumption that the academic programs meet that need,9,10 or because there are diagnostic methods available that have replaced the physical examination of the joints.11

The results of this study show that only 31/91 (34%) of the participants feel that there is enough literature on the topic, and the majority believes that a consensus is needed. So apparently, there is no formal examination method. This may be critical, since the joint examination is the foundation of clinimetrics, and of the assessment of activity in patients with RA, in addition to being essential of the T2T strategies designed to achieve good outcomes and lower costs. In the Colombian healthcare system, RA is classified as a high cost disease. A significant number of rheumatologists disagreed, or were not sure about the aspects of inflammation (swelling or edema) and the concept of joint pain. Relevant concepts in joint palpation, such as the thumb technique12 and the joint margin,8 were contradictory. Passive motion is one component of the joint examination, but almost half of the respondents said it was not essential. There were contradictory opinions about concepts such as joint range of motion, and deformities, when including this concepts in the clinimetrics definition. With regards to the general joint examination in a patient, approximately one fourth of the respondents felt that it should be done initially with the patient in a sitting position, and then laying down. In terms of the sequence of the examination, there were different opinions, but the most frequent was a top to bottom approach favored by one third of the rheumatologist. When asking about one technique for each joint, there was stronger agreement for the wrist, the elbow, the knee, the interphalangeal and the metatarsophalangeal joints; the rest of the joints had less agreement, except for the hip technique where there was less than 46% agreement. When asked about more than one technique for some of the joints, such as the metacarpophalangeal and the mid-tarsal joints, there was strong disagreement, probably because the techniques for examining each joint are not properly standardized. This was confirmed by the fact that most of the group expressed the need to develop a consensus.

The results indicate that there are differences of opinion with regards to the technique to examine the joints in RA clinimetrics; it is believed that standardization is the best option.6,7 The differences in concepts have been demonstrated and this is not exclusive for this particular scenario.13,14 Such heterogeneity in the examination and in the different concepts may result in misclassification of the disease activity, which has huge implications for the healthcare system and for the patients, in addition to the associated risks of inappropriate use of biologics (using biologics when not needed or not using them when needed).

The strength of this study is the large number of rheumatologists surveyed, representing the various regions of the country participating at the Assembly of the Colombian Association of Rheumatology.

The weakness of the study is that we are missing the opinion of those who did not participate in the survey or those who were not participating at the Assembly. Including them could lead to more representative results for the population of rheumatologists in the country, though there is no reason to believe that the opinion of those that did not participate could be any different. The demographics and the professional experience of the respondents were not considered and this could affect the answers; though there is some evidence that the years of experience of the examiner do not affect the results of the examination.15 Another weakness is that the survey was completed during the Assembly meeting, which could have affected the accuracy of the answers. Furthermore, the fact that the respondents were asked to write their name, could have influenced their answers. Finally, it is clear that failure to have a properly standardized joint examination is a critical issue in terms of the performance of the disease activity indexes; however, since the results are based on a survey, it is impossible to proof any differences, but the information may be valuable for future studies intended to determine the variation among the various practitioners.

ConclusionThere was a significant variation in the opinion about the concepts used in the joint examination of patients with RA to identify the swollen or painful joints. The best option would be to develop and adopt a standardized assessment process.

Conflict of interestsThe Colombian Association of Rheumatology received an unrestricted grant from Abbvie laboratories. Dr. Yimy F. Medina is the recipient of the grant. The other authors do not have any conflict of interests to disclose.

Please cite this article as: Medina-Velásquez YF, Narváez MI, Atuesta J, Díaz E, Motta O, Quintana López G, et al. Variación en la definición del examen articular para la clinimetría de la artritis reumatoide: resultados de una encuesta realizada a un grupo de reumatólogos colombianos. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2020;27:149–154.