To assess people's level of recognition of rheumatic disease symptoms and their awareness that the rheumatologist is the main effector when it comes to these disorders.

Materials and methodsSurvey performed in 8 towns in the Buenos Aires Province. Every town had at least one rheumatologist. Three clinical cases were presented: (1) inflammatory low back pain, (2) systemic disease, and (3) chronic polyarthritis. The population was asked whether (a) a physician should be immediately consulted, or (b) they could wait. They were asked whether they would advocate any initial treatment. They were also asked which physician should be consulted.

ResultsOut of 150 surveys, 68% were female, the average age was 51.7 years old. Most people asserted that treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs should come first: 83% in inflammatory low back pain, 70% in systemic disease, and 70% in chronic polyarthritis (p=0.02). The number of men that suggested waiting was higher (47% vs. 28% of women; p=0.04). A rheumatologist was recommended by 51% for chronic polyarthritis, 15% for systemic disease, and 8% for inflammatory low back pain (p<0.0001). Thirty-eight percent of those who never considered consulting a rheumatologist had elementary education vs. 19% of those who considered consulting a rheumatologist for one of the 3 cases (p=0.01)

ConclusionsChronic polyarthritis was the disease people identified best as within the rheumatologist's field of expertise. Men tended to delay consultation more than women. Consultation is less likely when the level of education is lower.

Evaluar el nivel de conocimiento de la población con respecto a los síntomas reumáticos y determinar si se reconoce al reumatólogo como el profesional que debe ser consultado en primer lugar ante su aparición.

Materiales y métodosEncuesta realizada en 8 localidades del interior de la provincia de Buenos Aires. Cada ciudad tenía al menos un reumatólogo. Se presentaron tres casos clínicos: (1) lumbalgia inflamatoria, (2) enfermedad sistémica y (3) poliartritis crónica. Se preguntó si (a) aconsejarían consultar a un médico de inmediato, o (b) aconsejarían esperar. Se preguntó si aconsejarían algún tratamiento y a qué médico aconsejarían consultar en primer lugar.

ResultadosSobre 150 encuestados, el 68% fueron mujeres y la edad promedio fue de 51,7 años. El 83% de los encuestados aconsejó usar antiinflamatorios en lumbalgia inflamatoria vs. 70% en enfermedad sistémica y 70% en poliartritis crónica (p=0,02). Los hombres sugirieron esperar con mayor frecuencia que las mujeres (47% vs. 28%; p=0,04). Un 51% de los encuestados recomendó consultar al reumatólogo en primer lugar en poliartritis crónica vs. 15% en enfermedad sistémica y 8% en lumbalgia inflamatoria (p<0,001). Entre aquellos que nunca consideraron consultar a un reumatólogo, el 38% tenía educación primaria vs. el 19% entre los que sugirieron consultar a un reumatólogo en alguno de los 3 casos (p=0,01).

ConclusionesLa poliartritis crónica fue la enfermedad mejor identificada dentro del campo de la reumatología. Los hombres tienden a retrasar la consulta con el médico. La consulta con el reumatólogo es menos probable cuanto menor es el nivel de educación.

Early diagnosis and treatment are of the utmost importance to control the progression of rheumatic diseases and improve patients’ prognosis. Since 1990, there is evidence that the prognosis of patients with rheumatoid arthritis improves if they are diagnosed in the early stages of the disease when the first symptoms appear.1 In the last few decades, it was observed that the lag time between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis was shorter in Europe and North America, but not in Latin America, an area of economic inequality and disparity in access to healthcare.2

Although Argentina has the highest number of rheumatologists per capita in Latin America, after Uruguay,3 a study performed by the Argentine Society of Rheumatology claims that it takes patients with RA 12 months to resort to a rheumatologist.4 The situation is even worse for those with ankylosing spondylitis. According to data from a cohort of 86 Argentine patients presented in the 2008 Argentine Congress of Rheumatology, 50% were diagnosed after 6 years.5

Buenos Aires is the most populated province in Argentina with 16 million inhabitants. It was verified that the region had 72% of the optimal number of rheumatologists per capita. However, due to the uneven resource distribution, 70% of the population did not benefit from an optimal level of rheumatology resources even if a rheumatologist was available in town.6

A study published in 2013 by the American College of Rheumatology evaluated the rheumatology resources in the United States of America and pointed out a well-defined disparity between the metropolitan areas and the rural areas or small towns.7

In this pilot study, a survey was carried out in towns relatively far from main urban centers. The aim was to assess people's level of recognition of rheumatic disease symptoms and their awareness that the rheumatologist is the main effector when it comes to these disorders.

Materials and methodsAn anonymous opinion survey was performed in the general population. Respondents should be 18 years of age or older. Open- and closed-ended questions were asked outside the rheumatology consultation setting. The survey was carried out in 8 towns of the Buenos Aires Province: Junín, Pergamino, Cañuelas, Rojas, Brandsen, Arrecifes, Olavarria and General Belgrano. They are, on average, 190km from the City of Buenos Aires, and have between 13,000 and 110,000 inhabitants. Every town has at least one rheumatologist.

Briefly, three clinical cases were presented: (a) case 1 is a 30-year-old man who works in a supermarket and has suffered from low back pain for 5 years. In the last few months, this pain wakes him up at night, and the morning stiffness recedes an hour after he gets up. From now on, this case will be referred to as inflammatory low back pain.

Case 2 is a 22-year-old girl who had skin rashes, fatigue, loss of appetite, and hand pain for 2 months. The skin rashes affect her face, neck and arms (sun-exposed areas) although she wears sunscreen on a regular basis. From now on, this case will be referred to as systemic disease.

Case 3 is a 55-year-old woman who is part of a school maintenance staff and has complained about hand, shoulder, knee and foot pain and swelling for the last 3 months accompanied by difficulty getting up and getting dressed in the morning. From now on, this case will be referred to as chronic polyarthritis.

- a)

Immediate medical consultation: the respondents were asked whether, in their opinion, those symptoms, (a) might be explained by general or work conditions, and thus they could wait before consulting a physician, or (b) accounted for an immediate medical consultation.

- b)

Suggested initial treatment: they were also asked whether they would advocate any initial treatment, and if so, what treatment would be advisable.

- c)

Initial waiting time: when the respondents answered that they could wait, they were requested to estimate for how long (in months).

- d)

Final consultation with a physician: they were asked what physician they thought they should ultimately consult and whether the case could be solved in their town or the patient should be referred to a center of higher complexity elsewhere.

Descriptive statistics was employed for the general analysis and the Student's t-test to compare averages. Both Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare medians as applicable. Nominal variables were analyzed by means of either a chi-squared test or by Fisher's exact test as appropriate.

A p<0.05 in the two-tailed test and a p<0.0167 in the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons were considered statistically significant. Epi Info version 3.5.4 was employed for the statistical analysis.

Ethical considerationsCompliance with Ethical Standards: since the following study was observational, it did not mean any risk, and it was anonymous, with no medical data of the participants being recorded, an informed consent was not required. The study was approved by the Teaching and Research Committee.

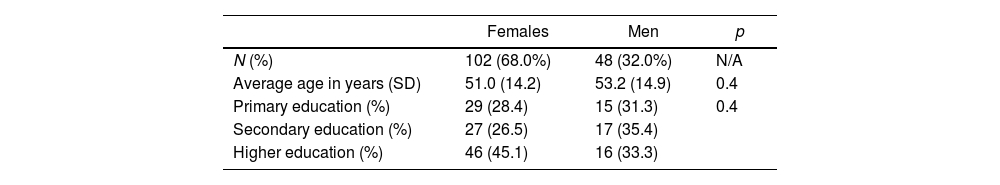

ResultsThe survey was answered by 150 individuals with an average age of 51.7 years old. Regarding the level of education, 44 respondents (29.5%) had elementary education, 44 (29.5%) had high school education, and 62 (41.0%) had higher education (see Table 1).

- A.

Immediate medical consultation: when the respondents were asked about the need for immediate medical consultation, most of them claimed that a physician should be immediately consulted in every case, but the proportion was lower for chronic polyarthritis (75% vs. 86% for inflammatory low back pain, and 86% for systemic disease; p=0.02). After the Bonferroni correction was calculated, these differences were non-statistically significant.

- B.

Suggested initial treatment: most people asserted that treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs should be performed first: 83% in inflammatory low back pain, 70% in systemic disease, and 70% in chronic polyarthritis (p=0.02). After the Bonferroni correction was calculated, differences were statistically significant for low back pain vs. systemic disease and chronic polyarthritis (p=0.007).

- C.

Initial waiting time: the suggested waiting time (median) was 1 month for systemic disease, 2 months for inflammatory low back pain, and 2.5 months for chronic polyarthritis (p=0.1). No statistically significant differences were observed as to age and level of education among those who recommended the immediate consultation and those who advised to wait. The number of men that thought it was prudent to wait in at least one of the 3 cases was higher than the number of women (47% vs. 28% respectively; p=0.04).

- D.

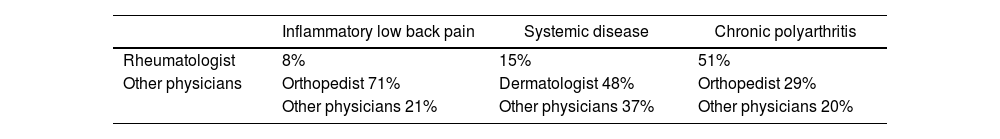

Final consultation with a physician: when asked what physician they should ultimately consult (see Table 2), (1) 51% answered they had to see a rheumatologist in the case of chronic polyarthritis vs. 15% in systemic disease, and only 8% in inflammatory low back pain (p<0.001). (2) After the Bonferroni correction was calculated, differences were significant for chronic polyarthritis vs. inflammatory low back pain and systemic disease (p<0.001).

Table 2.Physician of choice for final consultation with a physician according to clinical case (n=150).

Inflammatory low back pain Systemic disease Chronic polyarthritis Rheumatologist 8% 15% 51% Other physicians Orthopedist 71% Dermatologist 48% Orthopedist 29% Other physicians 21% Other physicians 37% Other physicians 20%

Respondents’ average age and level of education according to gender.

| Females | Men | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 102 (68.0%) | 48 (32.0%) | N/A |

| Average age in years (SD) | 51.0 (14.2) | 53.2 (14.9) | 0.4 |

| Primary education (%) | 29 (28.4) | 15 (31.3) | 0.4 |

| Secondary education (%) | 27 (26.5) | 17 (35.4) | |

| Higher education (%) | 46 (45.1) | 16 (33.3) |

Those who never even considered consulting a rheumatologist had a low level of education: 38% had only elementary school vs. 19% among those who considered consulting a rheumatologist in at least one of the 3 cases (p=0.01); there were differences neither in gender nor in average age.

Most of the respondents thought that the cases could be handled in their towns: 82% in the case of inflammatory low back pain, 86% in systemic disease, and 81% in chronic polyarthritis (these differences were non-statistically significant).

DiscussionWhereas a variety of studies focus on both quantifying rheumatology resources and the inequalities as to patients’ access to healthcare systems,8–13 there is very little research regarding the time that is wasted due to the scarce perception of the disease on the part of the population in general and the patients in particular, a non-specific factor that is of the utmost importance in inflammatory arthritis.14

A study, with the purpose of assessing people's knowledge about RA in Argentina, revealed that 29% did not know that rheumatic diseases could affect children and teenagers, and 19% did not know that they could cause deformity and disability.15

The fact that systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a heterogeneous disease characterized by autoimmune multi-organ compromise hinders the creation of strategies for early referrals. However, in most cases, the first symptoms are usually cutaneous and musculoskeletal.16 A study published in 2004 included 1,214 patients of the cohort of the Latin-American Group for the Study of Lupus (GLADEL) with a median diagnosis lag time of 6 months.17 The most frequently observed symptoms when the disease started were musculoskeletal (67.3%), cutaneous (46.3%), fever (28.6%), and weight loss (13%). Another study published in 2017, analyzed an extensive database from the United Kingdom and showed that before the diagnosis of SLE, the most significant increase is observed in the consultations owing to general complaints, musculoskeletal and mucocutaneous symptoms, in particular within the 6 months prior to the diagnosis.18 Consequently, while the model of systemic disease proposed in this survey (constitutional, cutaneous, and joint symptoms) is not the universal presentation pattern, it could foster early consultation on the part of the population, and early referral of SLE patients.

A study performed in 2000 in Spain assessed over 500 new patients with RA and underscored that those patients with higher levels of education, those who had family support (i.e., they did not live alone), and those who were active workers had made the initial appointment with the rheumatologist earlier.19 In a study carried out in Poland,20 197 adult patients who were being studied or had been recently diagnosed with inflammatory rheumatic diseases were asked what physician they had consulted before seeing a rheumatologist. Out of the 197 patients, 43% had seen an orthopedist. Before the first visit to the rheumatologist, 69% had taken analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs to relieve the joint symptoms. One of the few studies on RA diagnosis lag time in Latin America found that, in a hospital population in Venezuela, the initial consultation with an orthopedist or primary care physician was a variable associated with diagnosis lag time.21 In this study, it was observed that the decision to consult a rheumatologist was less frequent in people with low level of education. At least 70% of the surveyed populations mentioned anti-inflammatory drugs in the 3 cases, as a way of temporarily modifying the symptoms and postponing the visit to a physician. Out of 150 respondents, 29% considered consulting an orthopedist in the case of chronic polyarthritis, and 71% in the case of inflammatory low back pain.

It should also be emphasized that general practitioners’ usual unfamiliarity with rheumatic symptoms is another key factor that accounts for diagnosis lag time. As a case in point, although inflammatory low back pain is present in 70–80% of the patients with spondyloarthritis, it is not recognized by non-rheumatologists on a regular basis.5 In this survey, only 8% of the respondents suggested a consultation with the rheumatologist in the case of inflammatory low back pain. Therefore, there should be programs to train non-rheumatologists on the early detection of rheumatic symptoms.

In general, women are considered to sustain more symptoms than men and therefore, they consult general practitioners more frequently too.22 Nevertheless, the few and limited studies performed on RA do not determine whether such a claim is based on real data.23,24 In this survey, men had a higher trend to delay consultation than women.

This study has the following limitations: this is a pilot study and no validated questionnaires were used. Since no sampling method was used, 150 people may not be representative for the entire population. Data were obtained from populations far from main urban centers, so conclusions cannot be extrapolated to populations of big cities. As this survey was performed in the general population, some variables that might also interfere with the help-seeking process could not be appraised such as certain emotions people who sustain these disorders usually experience (denial, adaptation, minimizing, and so on), and the evolution of the disease (flares, rapid and progressive decline, and so forth).15 Although ever physician involved in the study went to great lengths to make a distinction between the survey and a rheumatology consultation, it is possible that small town respondents who knew the interviewing physician were biased towards early consultation.

However, these initial data can serve as a guideline to design strategies promoting early referral and reducing delays in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory arthritis. In light of the fact that there are multiple hindrances that impede the population's access to a rheumatologist, in order to achieve the objective of early consultation, it is imperative that the population identifies both the initial symptoms of a rheumatic disease and the rheumatologist as the suitable physician to diagnose and treat these disorders.

In summary, although most of the surveyed population suggested a medical consultation, this trend was low in men. Chronic polyarthritis was identified by half of the respondents as a disease within the rheumatologist field of expertise, and a significantly lower number mentioned rheumatologists as the main effectors in the other cases. Age did not seem to affect the decision to consult the rheumatologist, but the level of education did. Education programs on the early detection and referral of patients with rheumatic symptoms should be implemented among non-rheumatologists.

FundingThis research did not receive any kind of specific grant.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors wish to thank Prof. Ana Insausti for the collaboration in the translation of the study.