Government accounting (GA) and National accounts (NA) are two reporting systems that, although aiming different purposes, are linked – public administrations’ financial information for the latter is provided by the former. Therefore, the alignment between the two systems is an issue for the reliability of the public sector aggregates finally obtained by the National Accounts.

In the EU context, this is a critical issue, inasmuch as these aggregates are the reference for monitoring the fiscal policy underlying the Euro currency. However, while reporting in NA is accrual-based and harmonised under the European System of Regional and National Accounts, the GA each country still has its own reporting system, often mixing cash basis in budgetary reporting with accrual basis in financial reporting, hence requiring accounting basis adjustments when translating data from GA into NA.

Starting by conceptually analysing the accounting basis differences between GA and NA and the adjustments to be made when translating data from the former into the latter, this paper uses evidence from three southern European countries – Portugal, Spain and Italy, representing the southern Continental European accounting perspective, with cash-based budgetary reporting, and where budgetary deficits have been particularly significant in the latest years – to show how diversity and materiality of these adjustments may question the reliability of the budgetary deficits finally reported in NA.

The main findings point to the need for standardised procedures to convert cash-based (GA) into accrual-based (NA) data as a crucial step, preventing accounting manipulation, thus increasing reliability of informative outputs for both micro and macro purposes.

La Contabilidad Pública (CP) y las Cuentas Nacionales (CN) son dos sistemas de información contable que, aunque tienen distintos propósitos, están conectados – la información financiera de las administraciones públicas para el último es derivada del primero. Así, la armonización entre los dos sistemas es una cuestión importante a tener en cuenta en la fiabilidad de los agregados finales obtenidos por las Cuentas Nacionales.

En el contexto de la Unión Europea este es un tema crítico dado que los agregados de las Cuentas Nacionales sirven de referencia para la supervisión de la política presupuestaria ligada al Euro. No obstante, mientras la normativa en las CN es en la base de devengo y está armonizada por el Sistema Europeo de Cuentas Regionales y Nacionales, en la CP cada país tiene aún su propia normativa contable, muchas veces mezclando las base de caja en el informe presupuestario con el devengo en el informe financiero; por tanto, se requieren ajustes contables cuando se traslada la información de la CP a las CN.

En este artículo, se empieza analizando las diferencias conceptuales entre los sistemas contables de la CP y de las CN y los ajustes que se deben hacer cuando se trasladan los datos de la primera a las últimas. En la segunda parte del artículo se analiza empíricamente Portugal, España e Italia con el propósito de mostrar como la diversidad y materialidad de estos ajustes pueden cuestionar la fiabilidad de los déficits finalmente reportados en las CN. Estos países, donde los déficits tienen sido particularmente significativos en los últimos años, representan la perspectiva contable de los países del sur de Europa Continental con informe presupuestario en base de caja.

Los principales resultados apuntan la necesidad de crear procedimientos estandarizados para convertir los datos en base de caja (CP) en los en base de devengo (CN) que ayuden a prevenir la manipulación contable y así mejorar la fiabilidad de los outputs informativos para los propósitos micro y macro.

The relationship between Governmental accounting (GA – microeconomic perspective) and National accounts (NA – macroeconomic perspective) is assumed as a relevant issue to be studied, by authors such as Lüder (2000), Jones (2000a, 2000b, 2003), Montesinos and Vela (2000), Keuning and Tongeren (2004) and Hoek (2005). The main problem is to evaluate whether GA meets the NA requirements, namely regarding data provided by the General Government Sector (GGS). NA rules have been established in the UN System of National Accounts, adapted to the European context through the European System of Regional and National Accounts (ESA).1

This relationship is much more relevant and actual because, in spite of GA reforms over the last two decades, introducing accrual basis, two different accounting bases still coexist in GA systems – accrual basis for financial accounting and cash basis for budgetary accounting.2 On the other hand, regarding NA, all EU members-States must apply ESA rules for all economic sectors, including GGS that supports EU Treaty convergence criteria accomplishment – ESA requires full accrual basis, allowing some flexibility regarding taxes and social contributions.

Because of this difference in the accounting bases, several adjustments must be made when converting data from GA into NA, since the former are mostly cash-based, coming from budgetary reporting.

Subsequently, this paper starts by identifying, from the conceptual point of view, the major differences between GA and NA (namely concerning the recognition criteria – cash versus accrual basis), highlighting the main adjustments to be made when translating data from the former into the latter. The main purpose is to analyse the diversity and materiality of those adjustments, showing how they can question the reliability of final NA data (e.g. the deficit figures) reported by EU member-States to monitoring the Maastricht criteria these countries are obliged to accomplish with.

The paper relies on empirical evidence from three countries – Portugal, Spain and Italy, representative of the southern Continental European governmental accounting perspective, all using cash-based budgetary reporting, also embodying similar cultures and economic developments models, nowadays facing comparable difficulties in accomplishing with the EU convergence criteria.3 Data from Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) Notifications of October 2010 and October 2013, covering years 2006 to 2012 and Central Government, were used.

Analysing accounting basis differences between GA and NA and being one of the first attempts to quantify those differences, this study makes an important contribution both theoretically and for practice, calling attention to the need for further alignment between both reporting systems, in order to avoid adjustments management and reassuring Government Financial Statistics reliability.

The paper follows divided into three main sections. Section 1 discusses the relationship and differences between GA and NA. Section 2 addresses the main adjustments when translating data from one reporting system into the other. Section 3 analyses adjustments diversity and materiality, illustrating with data from the above-mentioned EU member-States. At last, some conclusions and final comments are presented.

2The relationship between governmental accounting and national accountsGA is aimed at running and reporting on one Government's budget, for purposes of financial management and accountability. It has evolved as Governments (broadly seen as including all governmental entities) have done, and as additional governmental information have revealed necessary within new contexts (Jones & Pendlebury, 2010).

In the last decades, under the New Public Management trends, new information requirements have been made to GA, which has therefore experienced considerable reform processes worldwide, which main common feature has been the introduction of accrual basis with a progressive approach to business accounting, particularly in what concerns financial accounting subsystems, thus moving to approach GA and NA, since the latter is already accrual-based (Benito, Brusca, & Montesinos, 2007; Brusca & Condor, 2002; Vela Bargues, 1996).

Nowadays, GA in general comprises two different subsystems: (i) budgetary accounting and reporting; and (ii) financial accounting and reporting. Budgetary subsystems support budgetary decisions regarding countries fiscal options, in a straight line with policy making, and report on budgetary achievements. Financial subsystems are related to governmental entities’ reporting in order to evaluate their performance and financial position.

Many international studies have shown that most countries that have adopted accrual basis in their GA, have not introduced it comprehensively, namely embracing budgetary systems, i.e. budget preparation and reporting of budgetary performance still remains cash or modified cash-based (Anessi-Pessina & Steccolini, 2007; Anessi-Pessina, Nasi, & Steccolini, 2008; Bastida & Benito, 2007; Benito & Bastida, 2009; Lüder & Jones, 2003; Sterck, 2007; Sterck, Conings, & Bouckaert, 2006). Only very few countries, like Australia, New Zealand and United Kingdom, have introduced full accrual basis in both subsystems (Martí, 2006; Montesinos & Brusca, 2009; Sterck et al., 2006), making them to be considered the leaders for the convergence between the two reporting systems, GA and NA (Broadbent & Guthrie, 2008). In Continental Europe, except for the cases of Switzerland and Austria, who recently introduced accrual-based budgets (Bergmann, 2012; Seiwald & Geppl, 2013), in most European Continental countries, e.g. Italy, France, Portugal, Belgium and Spain, budgets and budgetary execution and reporting are based on the cash or modified cash principle, hence both types of information (cash and accrued) coexist in GA (Montesinos & Brusca, 2009).

Therefore, in the EU context, there is still nowadays a problem of lack of harmonisation, as evidenced by the recent EU Commission Report concerning the suitability of IPSASs for the member-States, showing a great diversity of practices between member-States and also across different levels of government within each country (European Commission, 2013a, 2013b).

Otherwise, NA is essentially a statistical system focusing on five sectors within a single economy: two for business activities (finance and non-finance companies), one for non-profits entities, one for households and one for government, known as General Government Sector (GGS), to which GA is applied (Jones & Lüder, 1996; Jones, 2000a; Martí, 2006). This system works over an economics and statistically-based conceptual framework and applies to economic activities taking place within an economy and also between it and the rest of the world (IPSASB, 2012). Its purpose is to forecast and describe macro aggregates (e.g. gross domestic product, volume growth, national income, disposal income, savings and consumption) for a nation as a whole and the interaction between the different economic agents (Bos, 2008; IPSASB, 2012; Vanoli, 2005).

The establishment of a system of National Accounts was not made possible before the World War II, when for the first time issues regarding an internationally harmonised system were raised, leading to the first United Nations System of National Accounts in 1953, followed by revisions and new editions from 1960 to 1993 (Jones, 2000b; Vanoli, 2005). In 2008 an updated edition of the System of National Accounts (SNA2008)4 was issued, considered as a statistical framework that provides a comprehensive, consistent and flexible set of macroeconomic accounts for policy making, analysis and research purposes. SNA2008 is intended to be applied by all countries, having been considered different needs of countries at different stages of economic development.

At European level, the NA system firstly settled in the European Council Regulation n° 2223/96 (and subsequent amendments5) obliges all member-States to adopt the European System of National and Regional Accounts (ESA) in preparing their NA, so that since April 1999 all the information to be sent to the European Statistical Office (EUROSTAT) must conform to this system. Additionally, according to ESA95 §1.04, one of the specific purposes of this system is to support the control of the European monetary policy, namely the national aggregates as GDP, deficit and debt.

The reason why ESA (NA) was chosen as the system to monitoring those indicators is because it is a fully harmonised reporting system compulsorily applied to the whole of the European space, assuring data comparability, despite facing great diversity of political and social systems. Additionally, to support macroeconomic convergent budgetary and monetary policies, namely underlining the Euro currency (sustaining the European Monetary Union), NA seems to be the most adequate, since it provides comparable government finance statistics (Barton, 2007, 2011; Hoek, 2005; Keuning & Tongeren, 2004; Lüder, 2000).

As the recent report from the European Commission underlines (European Commission, 2013b), EU governments report two kinds of information: government finance statistics (NA) for fiscal policy purposes (including statistics for the EDP) and financial and budgetary reports for accountability and decision-making purposes relating to individual entities or groups of entities (GA). The relationship between the systems providing these two types of reporting is important, regarding both transparency (explaining to users the differences between the data in the respective reporting) and efficiency (GA budgetary systems are generally the main source of data for compiling government finance statistics – NA).

One question that might be raised concerns knowing whether the current GA systems, especially budgetary accounting and reporting systems, in the EU countries are able to meet ESA requirements, namely in what relates to data provided by the governmental sector. This is Sector S.13 – General Government Sector (GGS), following the definition of institutional sectors in ESA (§2.17). GGS was established in the Protocol on the EDP as the institutional sector in NA that supports the macroeconomic aggregates – deficit and debt – according to which the Maastricht Treaty convergence criteria are evaluated.

Therefore, in the relationship between GA and NA, the main problem concerns GGS data to NA, since they are obtained from GA budgetary information, which diversity and divergences to macro accounting systems may question the relevance, reliability and comparability of the aggregates that sustain financial decisions of EU member-States (Benito & Bastida, 2009; Lüder, 2000).

Some literature emphasises differences related to recognition criteria: under NA full accrual basis is preponderant, while GA considers, as stated before, a great diversity of accounting bases, mostly accrual for financial systems, but mainly cash/modified cash-based for budgetary systems (Barton, 2007; Cordes, 1996; Jones & Lüder, 1996; Lüder & Jones, 2003; Martí, 2006; Montesinos & Vela, 2000; Torres, 2004).

On the differences between GA and NA, the International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB) developed a working programme concerning the convergence of IPSASs with NA systems, starting in January 2005 with a Research Report (IPSASB, 2005), with the purpose of identifying differences in financial reporting provided by the statistical-based accounting systems (NA) and the financial information reported under the IPSASs (GA). In that Report emphasis was given to necessary adjustments to figures provided by GA concerning governmental sector, due to different measurement criteria of assets and liabilities, reducing reliability of macroeconomic aggregates.

Recently, the IPSASB issued a Project Brief designated “Alignment of IPSASs and Public Sector Statistical Reporting Guidance”. This document intends to be the starting point to update the 2005 Research Report, aiming at identifying the main issues regarding relevant differences between IPSASs and the updated SNA2008 and consequent updated Government Finance Statistics Manual. It emphasises the importance of statistical reporting as a public sector critical issue (IPSASB, 2011). This Project gave place to a Consultation Paper (IPSASB, 2012), which describes the relationship between IPSASs for accrual-based financial statements and Government Finance Statistics (GFS) reporting guidelines, reviewing progress since the IPSASB's last GFS harmonisation initiative, and identifying possible further opportunities to reduce the differences.

Australia seems to be the only country so far that produced a standard on Whole of Government and General Government Sector Financial Reporting (AASB, 2013).6 The standard identifies specific requirements to reconcile whole of government general purpose financial statements (GA) with General Government Sector financial statements (NA), so that the same recognition and measurement criteria must be applied in both financial statements sets. It also establishes requirements for additional information disclosures regarding reconciliations needed to ‘key fiscal aggregates’. Governmental financial statements and General Government Sector information in Australia must be prepared according to this standard requests, considering the usefulness of accounting information prepared and disclosed under three different accounting perspectives: cash-based and GAAP and accrual-based reporting, in the GA context; and GFS accrual-based reporting under NA (Barton, 2011; Kober, Lee, & Ng, 2010).

3Adjustments from GA data into NALiterature review and other documental sources allow identifying major specific issues related to the relationship and differences between GA and NA that need to be studied more deeply. These issues are essentially related to: (i) the definition and scope of reporting entity under GA and NA; (ii) the preparation and disclosure of consolidated financial statements; (iii) recognition criteria; and (iv) the relationship between government and government business enterprises (Jesus & Jorge, 2010, 2014). Of particular interest in this paper are issues comprised in category (iii).

As explained, each system (GA and NA) presents different criteria for transactions recognition. However, ESA95 general recognition criterion (accrual basis) was later made more flexible regarding taxes and social contributions, by EU Parliament and Council Regulation (EC) n° 2516/2000, allowing member-States to recognise these according to three different methods, thus becoming an exception to the accrual basis regime:

- •

Accrual basis – recognition when the taxes generating factor occurs;

- •

Adjusted cash basis – recognition of taxes under cash basis sources, considering a time adjustment when possible, so that the amounts received can be attributed to periods when the economic activity generating the fiscal obligation occurs;

- •

Cash basis – when it is not possible to apply none of the other methods.

Consequently, from GA-NA conceptual differences, mainly those regarding accounting basis divergences, arises the need to make adjustments from GA data into NA.

According to the Inventories of Sources and Methods7 (hereafter named Inventories) each EU member-State discloses, the main adjustment categories relate to: (i) cash/accrual adjustments for taxes, social contributions, primary expenditures and interest; and (ii) reclassification of some transactions, namely capital injections in State-owned corporations, dividends paid to GGS entities, military equipment expenditures and EU grants (Jesus & Jorge, 2014, 2015). The differences related to the definition and scope of reporting entity under GA and NA and the preparation and disclosure of consolidated financial statements are not explicitly mentioned in those Inventories.

Regarding cash-to-accrual adjustments, related to different recognition criteria, the Inventories describe the adjustments each country makes in order to transform cash-based into accrual-based data, considering issues such as taxes and social contributions and other receivables, interest, and primary expenditures. Analysing the Inventories, it can be observed that the procedures are not harmonised between countries, both in terms of the issues adjusted and in the way the adjustments are done (Jesus & Jorge, 2014, 2015).

As to reclassification adjustments, the procedures described in the Inventories are similar and concern to: (i) capital injections in State-owned corporations–analysing whether they meet the requirements of a financial transaction (not considered in the deficit/surplus) or of a non-financial transaction, considered in the deficit/surplus)8; (ii) dividends paid to GGS – according to ESA Manual on Government Deficit and Debt, each transaction is analysed in order to determinate whether the whole amount received from dividends can be considered as an income with positive impact on the deficit; (iii) military equipment expenditures (time differences adjustments regarding time of payment and time of delivery) and EU grants (time adjustments to assure neutrality of the Community grants).

Nevertheless, in this paper the research focuses on differences related to recognition criteria, namely concerning taxes and social contributions, accounts receivable/payable and interest paid/accrued. This focus is justified because material GA-NA differences relating to these criteria seem to exist – as NA collects micro data from several institutional sectors, it is necessary to make some adjustments, e.g. in order to harmonise the moment when transactions are recorded (Keuning & Tongeren, 2004; Lande, 2000; Lüder, 2000).

Keuning and Tongeren (2004) explain that accounting basis differences imply making adjustments and corrections based on estimations of GA data to determine the macroeconomic ratios, like deficit and debt, which has consequences on their reliability and comparability. They highlight this situation requires the adoption of accrual basis in GA and also a standardisation of procedures and practices among the two systems. Their study on the relationship between GA and NA applied to The Netherlands, describes the main steps that must be considered when taking data sources of governmental sector into NA, and underlines the adjustments related to the transformation of cash-based (GA) into accrual-based data (NA) – identifying the proper asset and transaction category; consolidating some internal flows; adjusting time of recognition of taxes, interest payments on central government debt, and payments in advance, among others.

On her hand, Martí (2006) underlines cash-based budgeting has a fundamental problem to be solved in the relationships between GA and the NA aggregates that allow comparing countries’ financial performance. The author discusses the key items with different accounting recognition alternatives, such as the recognition of taxes and social contributions revenues and the accounting treatment of infrastructures, heritage collections and military equipment.

While sustaining that macro statistical data must be used only for NA purposes and not at micro level, Hoek (2005) and Benito et al. (2007) emphasise the position of other authors (e.g. Jones, 2000a, 2000b; Lande, 2000; Lüder, 2000; Montesinos & Vela, 2000), arguing in favour of searching a link between GA and NA, due the inconsistence of the two systems, compromising the usefulness and reliability of the information for both micro and macro level.

Looking at the Australian case, Australia seems to be a leader country in approximating both systems, as in the last reforms carried out, NA outputs are used to government accounting purposes (Barton, 2011).

In the EU context, GA-NA adjustments may be measured through the EDP Reporting Notifications9 each country is obliged to report to EUROSTAT twice a year. Table 2A in those EDP Notifications provides data related to Central Government deficit/surplus reported by EU member-States, explaining the transition from Central Government accounts budgetary execution deficit/surplus in GA into Central Government final deficit/surplus in NA.

Central Government accounts budgetary execution deficit/surplus, designated as ‘working balance’, represents the balance between all revenues and expenditures. Table 2A evidences data adjustments to reach final deficit/surplus – net borrowing/lending of Central Government Sector (S.131), according to NA requirements. The ‘working balance’ concerns mostly to budgetary execution deficit/surplus of the subsector State (S.13111) as the deficit/surplus of other Central Government entities is disclosed as a whole in a separate item. However, in some countries the ‘working balance’ is cash-based while in other countries is already reported under accrual basis. Analysing the Inventories, one can state that some countries display mixed accounting basis, meaning they use cash to some transactions and accruals to others.

As Dasí, Montesinos, & Murgui (2013) stated, the ‘working balance’ in GA must be adjusted for net lending/borrowing in NA and those adjustments can be classified into four categories: (1) adjustments resulting from differences in the classification of transactions between financial or non-financial public budget and National Accounts; (2) adjustments resulting from differences in the time of recording, basis of recognition and the time period; (3) adjustments resulting from differences in the delimitation of the sector; and (4) other adjustments.

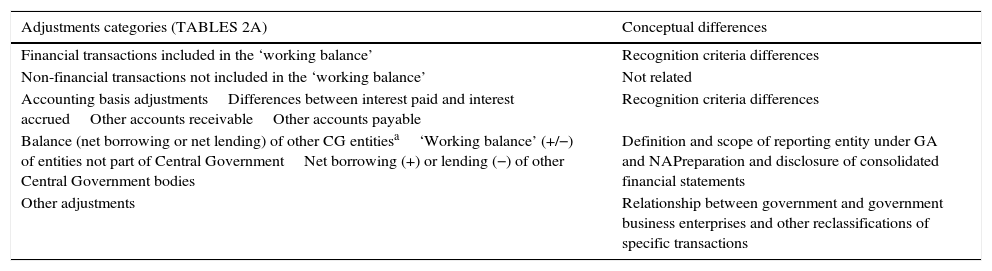

From the GA-NA adjustment categories made to Central Government ‘working balance’ in GA to reach Central Government final deficit/surplus in NA, it can be observed that some are related to the conceptual differences identified in Section 1 while other are not, as it is shown in Table 1.

Adjustment categories and conceptual differences between GA and NA.

| Adjustments categories (TABLES 2A) | Conceptual differences |

|---|---|

| Financial transactions included in the ‘working balance’ | Recognition criteria differences |

| Non-financial transactions not included in the ‘working balance’ | Not related |

| Accounting basis adjustmentsDifferences between interest paid and interest accruedOther accounts receivableOther accounts payable | Recognition criteria differences |

| Balance (net borrowing or net lending) of other CG entitiesa‘Working balance’ (+/−) of entities not part of Central GovernmentNet borrowing (+) or lending (−) of other Central Government bodies | Definition and scope of reporting entity under GA and NAPreparation and disclosure of consolidated financial statements |

| Other adjustments | Relationship between government and government business enterprises and other reclassifications of specific transactions |

This research essentially follows a descriptive methodology, since the purpose is to describe, analyse and compare accounting practices, focalising on a particular context and pursuing a systematic, integrated and broader approach (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Ryan, Scapens, & Theobald, 2002).

It uses qualitative and quantitative data together, following a research design as suggested by Miles and Huberman (1994). It adopts a multiple case research method (Sterck, 2007), namely an explorative multi-country case study (Lüder, 2009), applying a comparative-international perspective as those from Torres and Pina (2003) and Martí (2006).

The empirical study develops a comparative analysis focused on three EU countries – Italy, Portugal and Spain, representing the southern European Continental countries, influenced by administrative law, with a hierarchical public administration, as Brusca and Condor (2002), Torres and Pina (2003) and Torres (2004) highlight.

These countries were selected because they have the above referred similar features, but they also present differences that justify the comparison. While Italy and Spain have three tiers of government, including regional governments, in Portugal there are only Central and Local Government. In terms of public sector accounting, they are Continental European countries that generally have followed GA reforms trends, namely within the EU countries, gradually introducing accrual basis in their financial systems in all levels of government – Spain has introduced IPSAS in 2010, Portugal and Italy are currently in the process of approaching IPSAS. Neither of these countries uses accrual-based budgets, but still cash-based budgetary reporting, but while Portugal and Italy report to EUROSTAT the ‘working balance’ in a cash basis, Spain already reports in accrual basis.

The main documental source is, for the three countries, the respective EDP Consolidated Inventory of Sources and Methods (EUROSTAT, 2009a, 2009b; INE, 2007).10 These documents present, for each country, a description of sources and methods to be used in the preparation of the EDP Notification Tables, as explained in Section 2.

Quantitative data were collected from Excessive Deficit Procedure Notifications – October 2010 and October 2013 (EDP, Table 2A), covering years 2006 to 2008 and 2009 to 2012, respectively. As explained before, Table 2A provides data explaining the transition from the public sector accounts budget deficit/surplus in GA, designated as ‘working balance’, into the final deficit/surplus in NA, regarding Central Government Sector (EUROSTAT, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c).

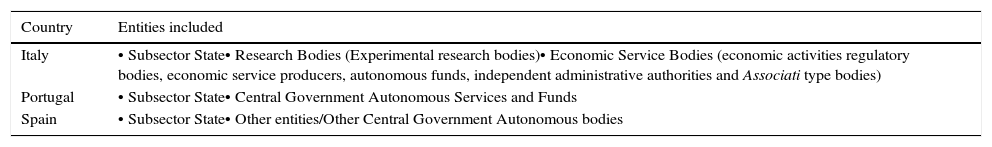

As Central Government Sector (S.131) is our object of analysis, it is important to clarify its delimitation for each country in order to better understand the data sources from GA into NA and consequent accounting basis adjustments. Table 2 shows the entities included in the Central Government Sector in NA by country.

Delimitation of Central Government Sector.

| Country | Entities included |

|---|---|

| Italy | • Subsector State• Research Bodies (Experimental research bodies)• Economic Service Bodies (economic activities regulatory bodies, economic service producers, autonomous funds, independent administrative authorities and Associati type bodies) |

| Portugal | • Subsector State• Central Government Autonomous Services and Funds |

| Spain | • Subsector State• Other entities/Other Central Government Autonomous bodies |

Regarding Central Government Sector, Italy and Portugal moved from cash into accrual accounting in the agencies’ financial systems,11 remaining the subsector State's bodies almost all cash-based; in both countries budgetary systems are still cash-based. Concerning Spain, all Central Government entities already adopt accrual basis, although budgetary accounting and reporting subsystem is still cash-based. However, while reporting to EUROSTAT, GA budgetary balance is already stated as accrual-based (EUROSTAT, 2010c, 2013c), meaning that some adjustments GA-NA are made before the reporting procedure and consequently less adjustments are required a posteriori.

4.2Diversity of the accounting basis adjustmentsAs explained, the Inventories describe the main adjustments from GA ‘working balance’ into NA final deficit/surplus. These adjustments are classified into two categories, one related to reclassification of some transactions and other concerning cash-accrual adjustments (Jesus & Jorge, 2010, 2014).

This research explores the cash-accrual adjustment category – accounting basis adjustments, detailed in the following groups: (1) taxes and social contributions; (2) other accounts receivable and other accounts payables (primary expenditures); and (3) differences between interest paid and accrued.

Concerning the countries analysed, Portugal and Italy describe in their Inventories adjustments of all categories above mentioned, while Spain only describes adjustments related to interest paid and accrued, since this country already reports information from GA mostly accrual-based.

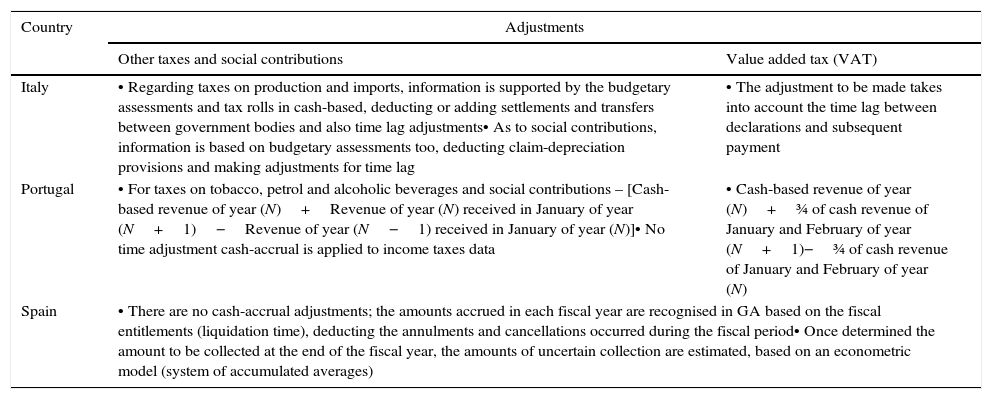

Tables 3–5 detail the adjustments procedures relating the three types of cash-accruals adjustments, considering each country's Inventory.

Adjustments procedures relating to “taxes and social contributions”.

| Country | Adjustments | |

|---|---|---|

| Other taxes and social contributions | Value added tax (VAT) | |

| Italy | • Regarding taxes on production and imports, information is supported by the budgetary assessments and tax rolls in cash-based, deducting or adding settlements and transfers between government bodies and also time lag adjustments• As to social contributions, information is based on budgetary assessments too, deducting claim-depreciation provisions and making adjustments for time lag | • The adjustment to be made takes into account the time lag between declarations and subsequent payment |

| Portugal | • For taxes on tobacco, petrol and alcoholic beverages and social contributions – [Cash-based revenue of year (N)+Revenue of year (N) received in January of year (N+1)−Revenue of year (N−1) received in January of year (N)]• No time adjustment cash-accrual is applied to income taxes data | • Cash-based revenue of year (N)+¾ of cash revenue of January and February of year (N+1)−¾ of cash revenue of January and February of year (N) |

| Spain | • There are no cash-accrual adjustments; the amounts accrued in each fiscal year are recognised in GA based on the fiscal entitlements (liquidation time), deducting the annulments and cancellations occurred during the fiscal period• Once determined the amount to be collected at the end of the fiscal year, the amounts of uncertain collection are estimated, based on an econometric model (system of accumulated averages) | |

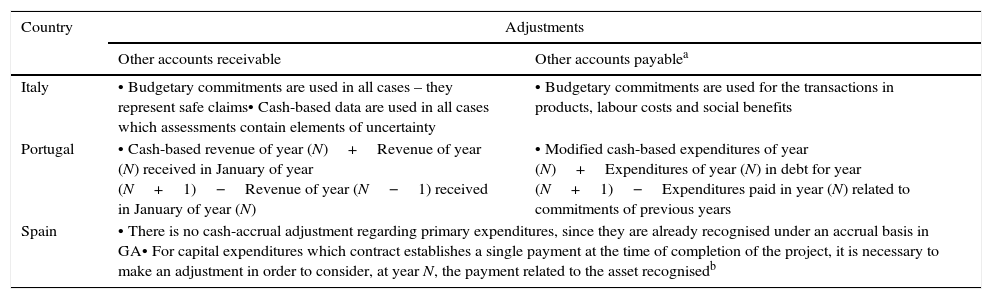

Adjustments procedures relating to “other accounts receivable/payable”.

| Country | Adjustments | |

|---|---|---|

| Other accounts receivable | Other accounts payablea | |

| Italy | • Budgetary commitments are used in all cases – they represent safe claims• Cash-based data are used in all cases which assessments contain elements of uncertainty | • Budgetary commitments are used for the transactions in products, labour costs and social benefits |

| Portugal | • Cash-based revenue of year (N)+Revenue of year (N) received in January of year (N+1)−Revenue of year (N−1) received in January of year (N) | • Modified cash-based expenditures of year (N)+Expenditures of year (N) in debt for year (N+1)−Expenditures paid in year (N) related to commitments of previous years |

| Spain | • There is no cash-accrual adjustment regarding primary expenditures, since they are already recognised under an accrual basis in GA• For capital expenditures which contract establishes a single payment at the time of completion of the project, it is necessary to make an adjustment in order to consider, at year N, the payment related to the asset recognisedb | |

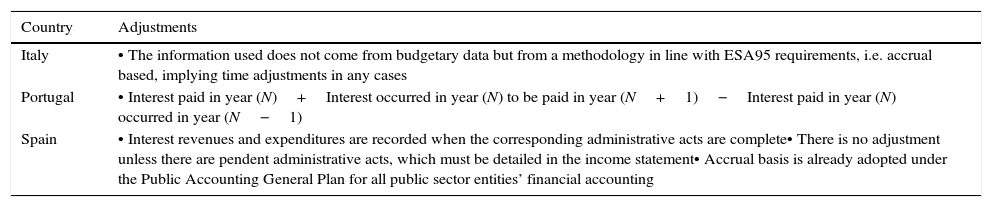

Adjustments procedures relating to “difference between interest paid and accrued”.

| Country | Adjustments |

|---|---|

| Italy | • The information used does not come from budgetary data but from a methodology in line with ESA95 requirements, i.e. accrual based, implying time adjustments in any cases |

| Portugal | • Interest paid in year (N)+Interest occurred in year (N) to be paid in year (N+1)−Interest paid in year (N) occurred in year (N−1) |

| Spain | • Interest revenues and expenditures are recorded when the corresponding administrative acts are complete• There is no adjustment unless there are pendent administrative acts, which must be detailed in the income statement• Accrual basis is already adopted under the Public Accounting General Plan for all public sector entities’ financial accounting |

Accordingly, regarding “taxes and social contributions”, a very important topic of possible adjustments, the countries analysed present a great diversity of treatments. Cash and accrual data are used and there are different adjustments for the same items of taxes and duties, mentioned in the three countries Inventories. Additionally, in each country, different accounting bases are applied according to different tax categories.

As to “other accounts receivable/payable”, Italy reports accounts payable based on budgetary commitments, although not explaining any adjustment associated to this category. Portugal describes cash-accruals adjustments for both groups, while Spain in general does not address any adjustment regarding this category, with the rare exception of capital expenditures in very particular situations, as noted in Table 4, since the ‘working balance’ in GA is reported in NA as already accrual-based.

Spain only describes adjustment procedures to “interest paid and accrued” in particular cases, since interest is already recognised essentially in accrual basis in the GA ‘working balance’. On the contrary, in both Portugal and Italy, time adjustments are disclosed since, within GA, interest is still recorded as cash-based. Only Portugal discloses detailed procedures do this adjustments category.

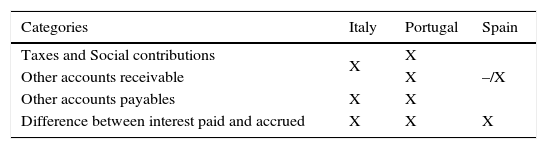

Table 2A discloses four specific categories relating to cash-accruals adjustments, similar to those identified under the Inventories. However, when analysing each country's Table 2A, countries sometimes do not do as they state in the Inventories. This might be another issue to add to diversity, again questioning reliability. In the cases and period analysed, such happens for Italy, which does not display the category designated “taxes and social contributions” separately, in spite of the procedures detailed in the Inventories (EUROSTAT, 2009b, 2010a, 2013a). As to Spain, despite the Inventories essentially explaining adjustments concerning “interest paid and accrued”, Table 2A disclose adjustments concerning taxes, included in “other accounts receivable” as temporal adjustments in taxes and included in “other accounts payable” as tax reimbursements. However these two categories are only reported as from 2009 onwards, i.e. from October 2013 EDP Notification (EUROSTAT, 2009a, 2010c, 2013c). Table 6 evidences these circumstances.

In conclusion, the above analysis shows the existence of several adjustments categories in the countries analysed, implying a vast number of procedures. Adding to this diversity, there are also different accounting treatments each country makes while translating data from GA into NA, specifically due to the fact that they use different accounting basis in budgetary accounting and reporting within GA. Finally, there are also discrepancies between what countries state they do as adjustments (Inventories) and the adjustments they really do (Table 2A), more obvious in the case of Spain.

All these diversities raise doubt about the reliability of the deficit finally reported in NA by each country, also questioning the inter-countries crucial comparability that is necessary when assessing the accomplishment by EU member-States of the convergence criteria.

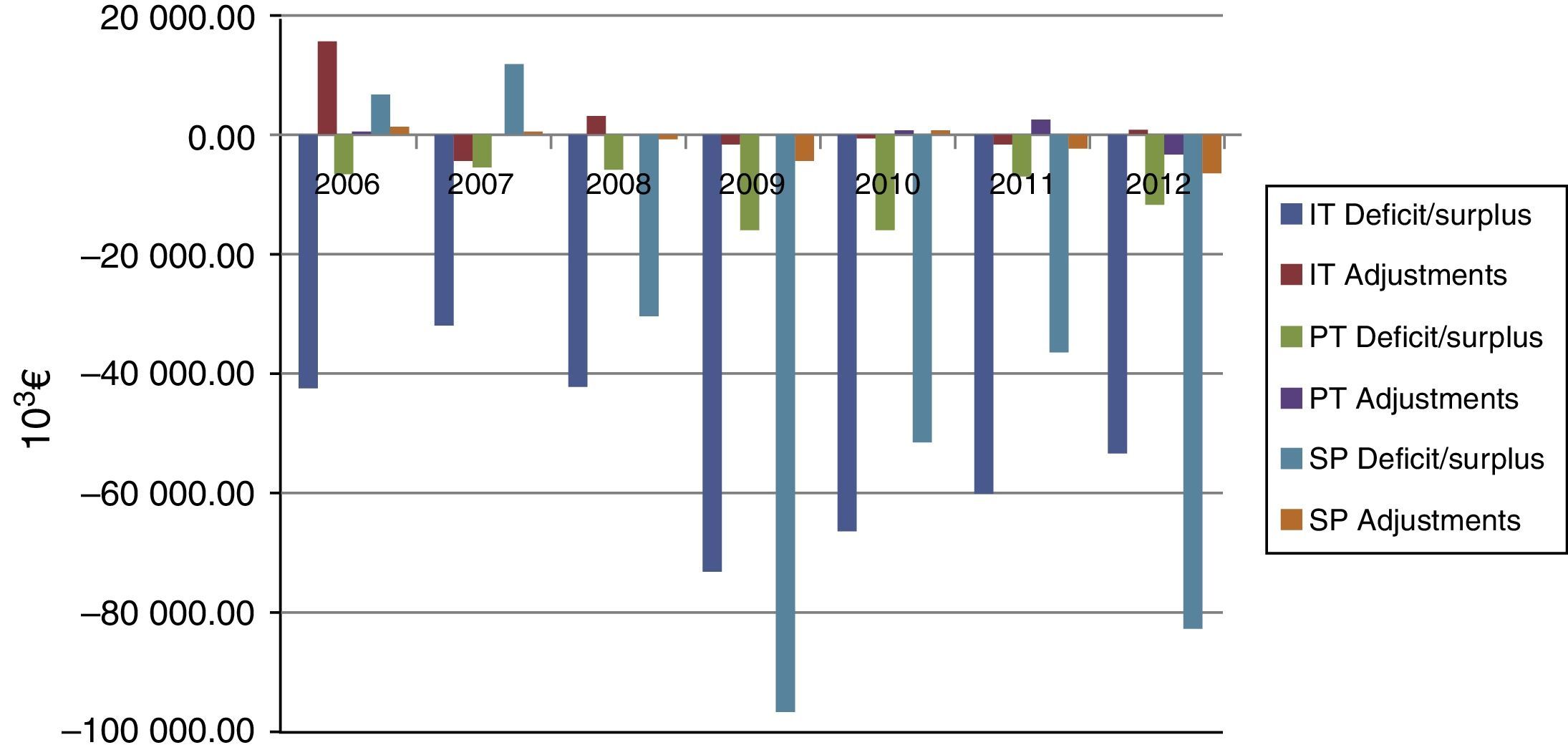

4.3Materiality of the accounting basis adjustmentsThe quantitative impact of the accounting differences between GA and NA on the Central Government deficit/surplus reported by the three counties analysed, is evaluated, as explained, using data reported in Table 2A from the October 2010 and October 2013 EDP Notifications, covering years 2006 to 2012.

Regarding Portugal and Spain, the ‘working balance’ in Table 2A concerns only to the subsector State data as the deficit/surplus of other Central Government entities is disclosed as a whole in a separate item (Jesus & Jorge, 2014, 2015). The Italian ‘working balance’ reports the Central Government deficit/surplus for all entities included in this subsector (EUROSTAT, 2010a, 2013a).

As to accounting bases, the ‘working balance’ is supported in cash-based budgetary reporting (balance from expenditures and revenues) in Portugal and Italy. However, these countries’ Central Government reporting is cash-based for the subsector State and accrual-based for most of the other Central Government entities. The ‘working balance’ data is reported in accrual basis in the Spanish notifications (EUROSTAT, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c).

This analysis of the cash-accrual GA-NA adjustments materiality follows using two dimensions: a temporal dimension comprising an analysis per year, and a spatial dimension concerning the analysis per category.

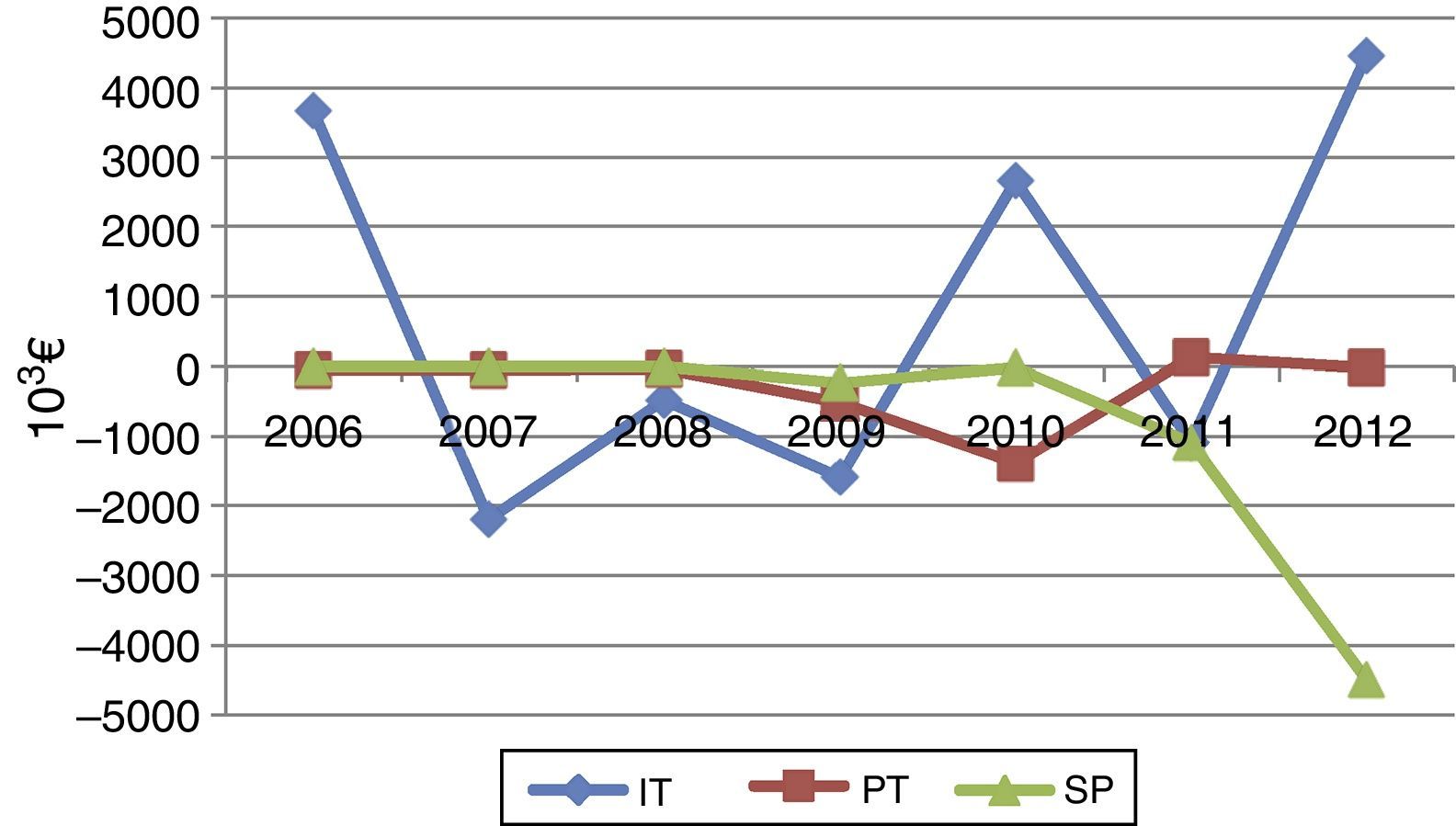

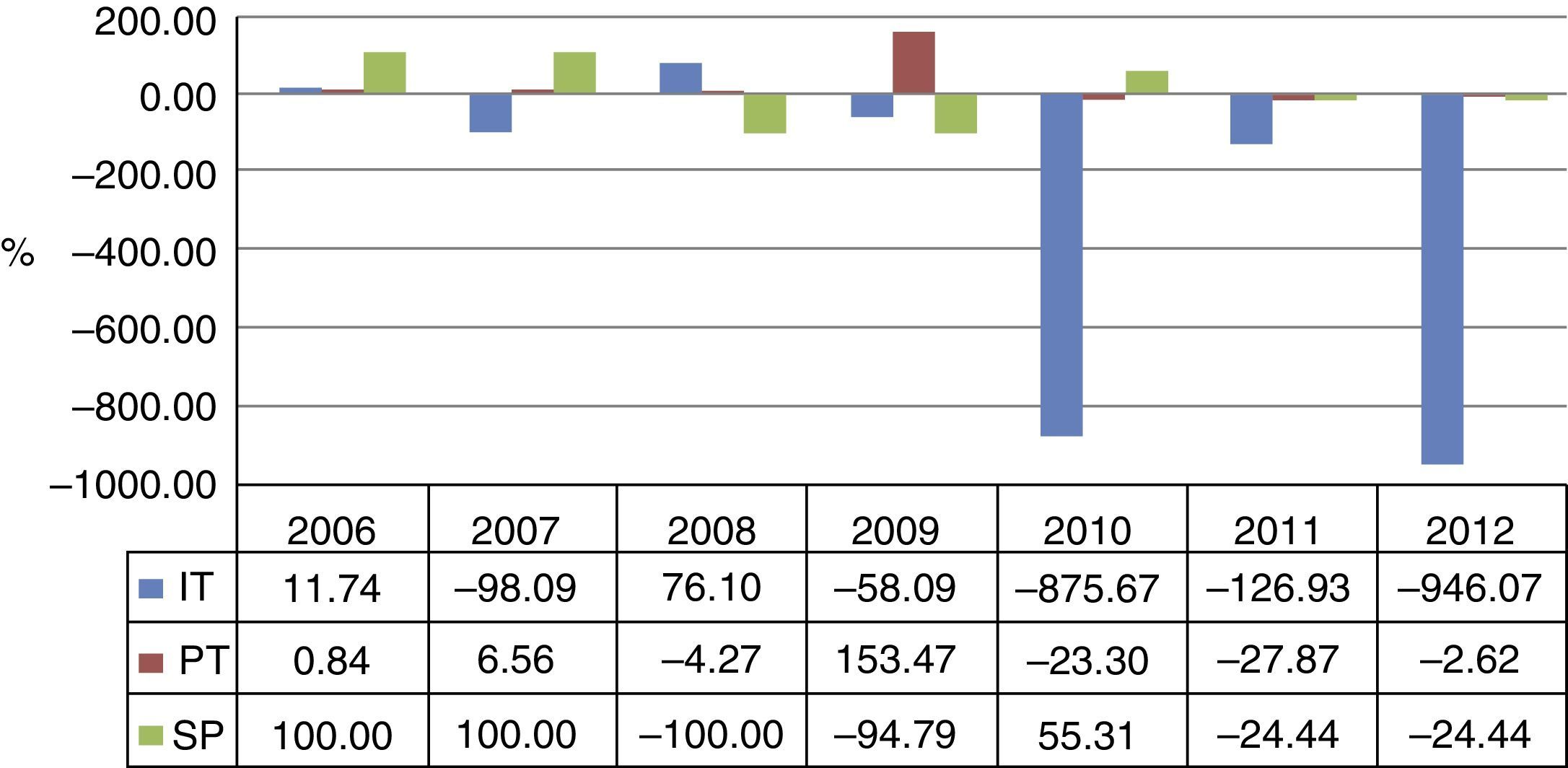

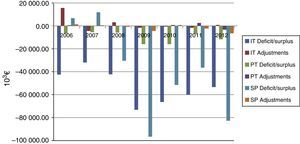

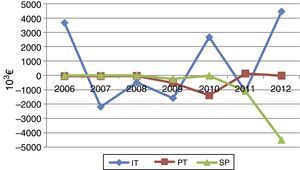

4.3.1Analysis per yearFig. 1 compares the total amount of GA-NA accounting basis adjustments with the amount of NA final deficit/surplus (considered after all the adjustments made to the GA ‘working balance’ in Central Government accounts).

It also allows observing whether the impact of the cash-accrual adjustments total on the deficit/surplus is either positive (reducing the deficit or increasing the surplus) or negative (the opposite).

It can be observed that regardless of the sign of the impact on the deficit/surplus (positive or negative), GA-NA cash-accrual adjustments show some materiality, particularly in Italy in the first two years of analysis (2006–07), and in Portugal in the last two (2011–12). In these countries, which still report GA deficit/surplus in a cash basis, materiality of cash-accrual adjustments has evolved in opposite directions – generally decreasing in Italy and increasing in Portugal, from 2006 to 2012. In Spain (which already reports GA deficit/surplus in accrual basis in Table 2A but still uses cash-based budgetary reporting) adjustments are more material in 2006 and then again in 2011–12.

In all countries cash-accrual adjustments materiality increases in the last two years, being higher in Portugal. This might be related to the fact that, all under financial pressure, these countries were concerned in reaching the targets for the final deficits agreed, so they might have been obliged to report more adjustments in order to show the most accurate deficit.

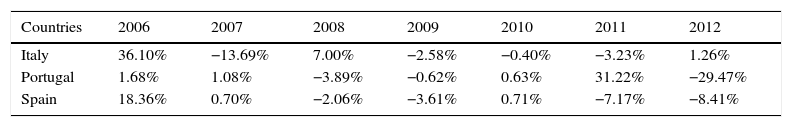

Table 7 reinforces the analysis, showing values in percentage.

Total accounting basis adjustments versus deficit/surplus (%).a

| Countries | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 36.10% | −13.69% | 7.00% | −2.58% | −0.40% | −3.23% | 1.26% |

| Portugal | 1.68% | 1.08% | −3.89% | −0.62% | 0.63% | 31.22% | −29.47% |

| Spain | 18.36% | 0.70% | −2.06% | −3.61% | 0.71% | −7.17% | −8.41% |

Note: The sign represents the impact on the deficit/surplus.

Considering the sign of the impact of the adjustments, while in 2006 the effect of the adjustments was positive in all countries, increasing the final surplus in Spain and decreasing the final deficit in Portugal and in Italy, in 2009 it was negative, increasing the final deficit in all countries. In 2011 the positive effect is striking in Portugal, inasmuch as cash-accrual adjustments contribute to reduce the final deficit presented in NA in approximately 31%; however, in 2012 the effect in the opposite, increasing the deficit in about 29.5%. In Spain the effect is also negative in the last two years, increasing the final deficit in about 8%.

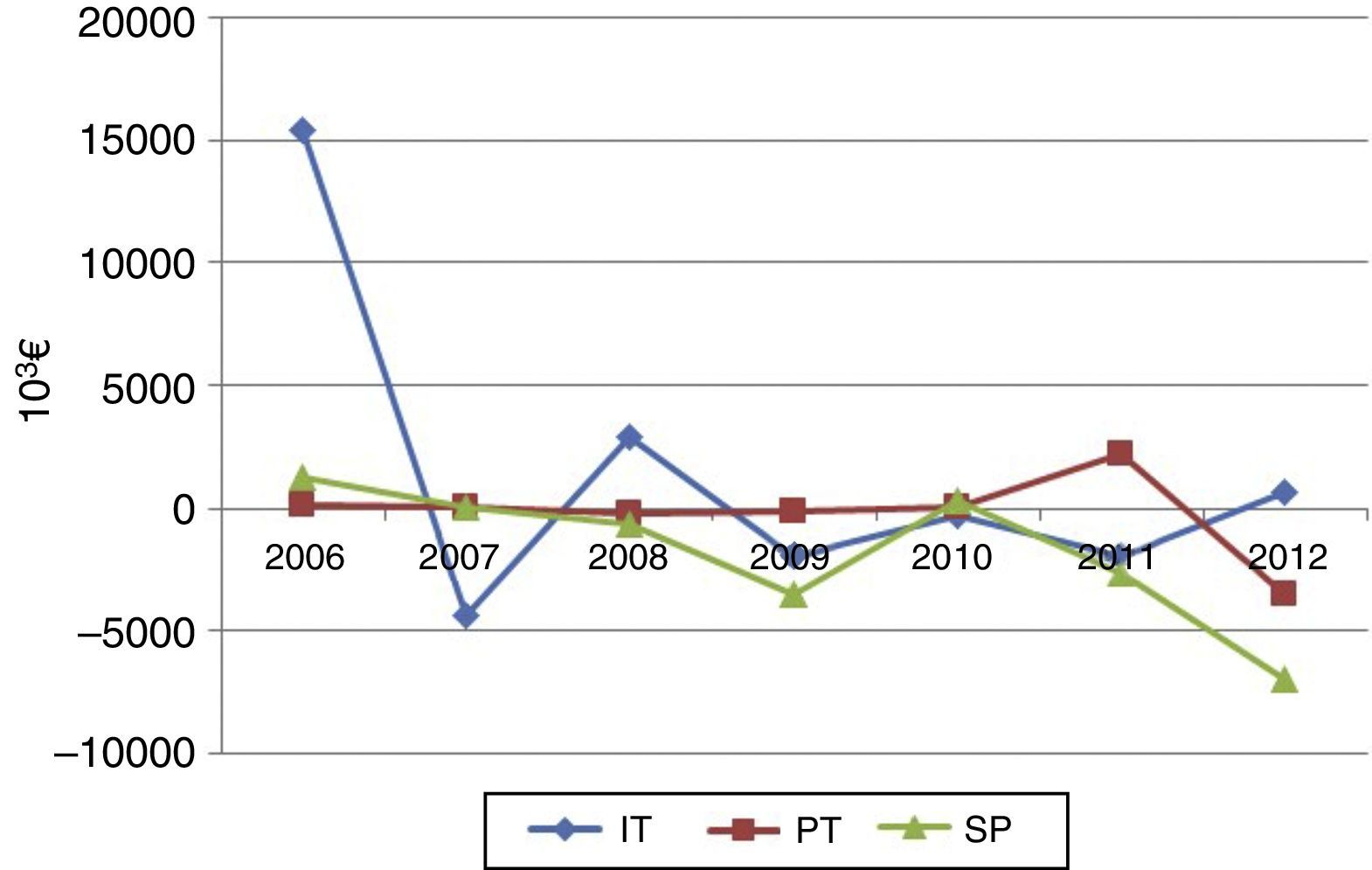

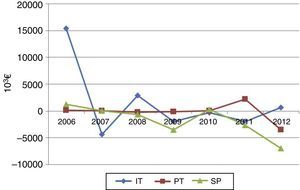

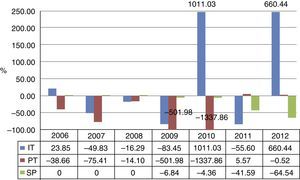

Fig. 2 illustrates the evolution of all cash-accrual adjustments along the analysed period.

Overall, it can be observed that GA-NA cash-accrual adjustments generally oscillate over these years for all countries, but particularly regarding Italy in the first years of analysis. In Spain oscillation increase from 2009 and in Portugal from 2010. This adds to the above analysis showing that adjustments amount is not constant, reinforcing the idea that these adjustments possible influence on the final deficit/surplus reported, might be used differently in different years.

All in all, GA-NA accrual basis adjustments materiality is an issue to be considered when seeking reliable and accurate NA deficit/surplus in EDP reporting in the EU. The importance of this matter in enhanced considering that these adjustments can impact positively or negatively on the final deficit/surplus figures, so countries might take advantage of this.

4.3.2Analysis per categoryAs the cash-accrual adjustments result from a sum of different adjustments types, positively and negatively impacting on the deficit, it is important to analyse each category individually, because each one has dissimilar weights and presents different evolutions. Such analysis enables to highlight materiality purging a possible compensation effect, yet considering the impact on the deficit.

Therefore, adding to the previous analysis, within the materiality of the total cash-accrual adjustments already discussed, special attention must be paid to the adjustment categories with higher relative weights, drawing attention to the accounting treatment given to these types of transactions when reconciling GA-NA deficits/surpluses.

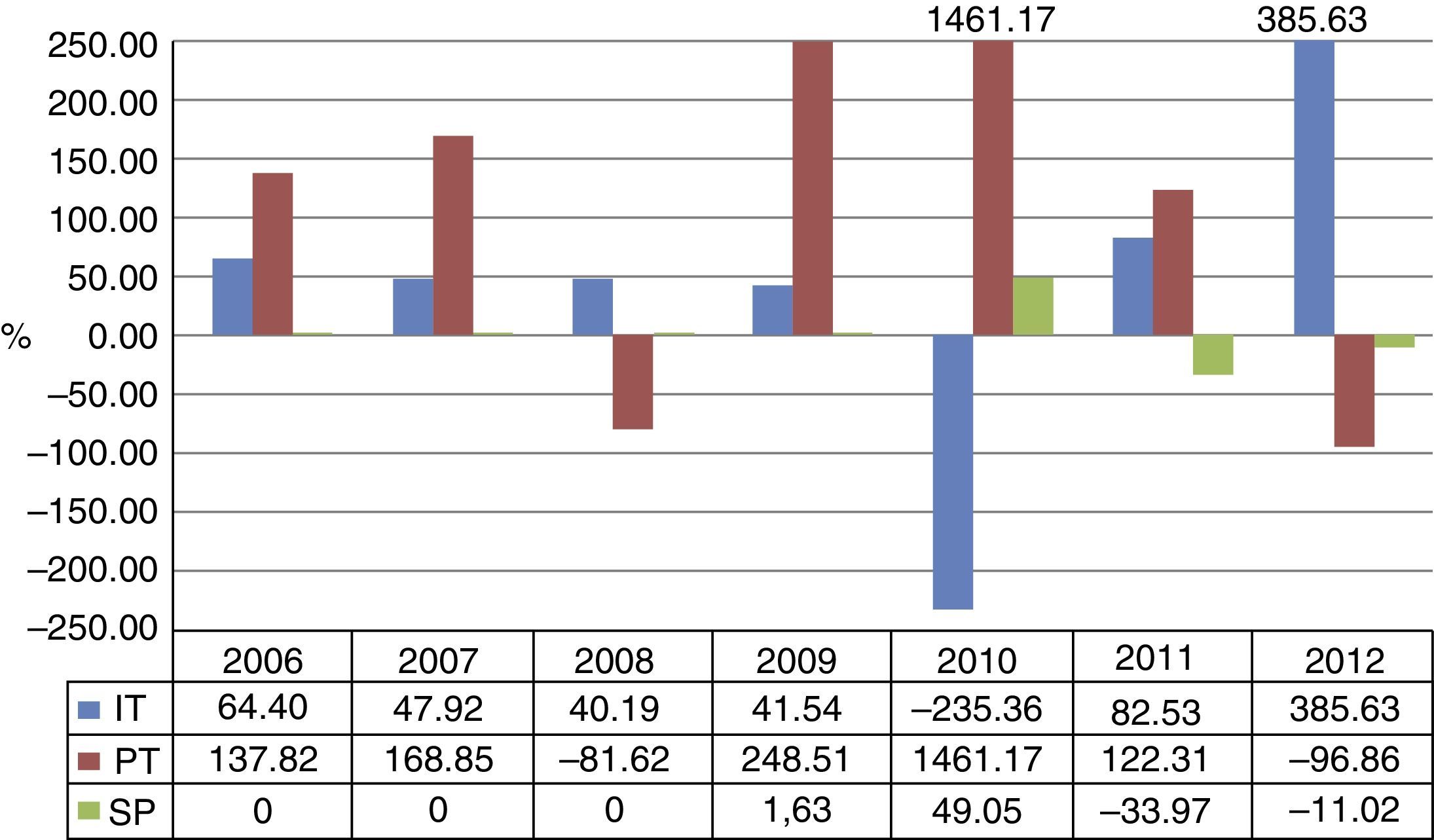

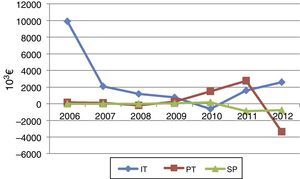

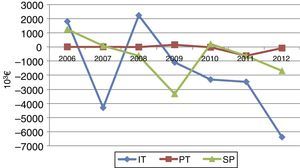

Accordingly, Figs. 3 and 4 concern the category “other accounts receivable” (including taxes and social contributions12), showing the evolution and the weight in percentage of this category on the total of cash-accrual adjustments as a whole.

In general, the evolution analysis shows clearly two different periods – before 2009 and after 2009. In the first, there was a regular trend for Portugal, with absolute amounts very close to zero; Spain did not disclose adjustments in this category; and Italy reported much higher amounts, yet showing a decreasing tendency, namely from 2006 to 2007. In the second period, Spain started to present adjustments in this category (concerning temporal adjustments in taxes, as explained); Italy and Portugal presented amounts that oscillated significantly from year to year; and Portugal showed from 2010 the highest amounts of adjustments in this category, regardless the sign of the impact on the deficit/surplus.

The growth of the amount of this adjustment category in 2011 in Portugal and Italy might relate to tax increasing happened in those years, in both countries still recognised in cash-basis in GA, so requiring adjustments when translating into NA. In Spain, even if there was also tax increasing, no adjustments were supposed to be required, since taxes, as other accounts receivable, are allegedly recognised under accrual basis (see Table 3). Therefore, the amounts disclosed might relate to corrections that had been made.

Moreover, this category presents higher weights in the Portuguese case, regardless the sign of the impact on the deficits. Except in 2008 and 2012, it represents more than 100% of the adjustments total, being compensated by other categories as showed in Fig. 4. Italian weights also evidence huge materiality, ranging from a minimum of 40% of the cash-accrual adjustments as a whole in 2008 to a maximum of 386% in 2012, regardless the sign of the impact on the deficits. 2010 is the year where this category of adjustments reaches the highest weights in the total, for all countries.

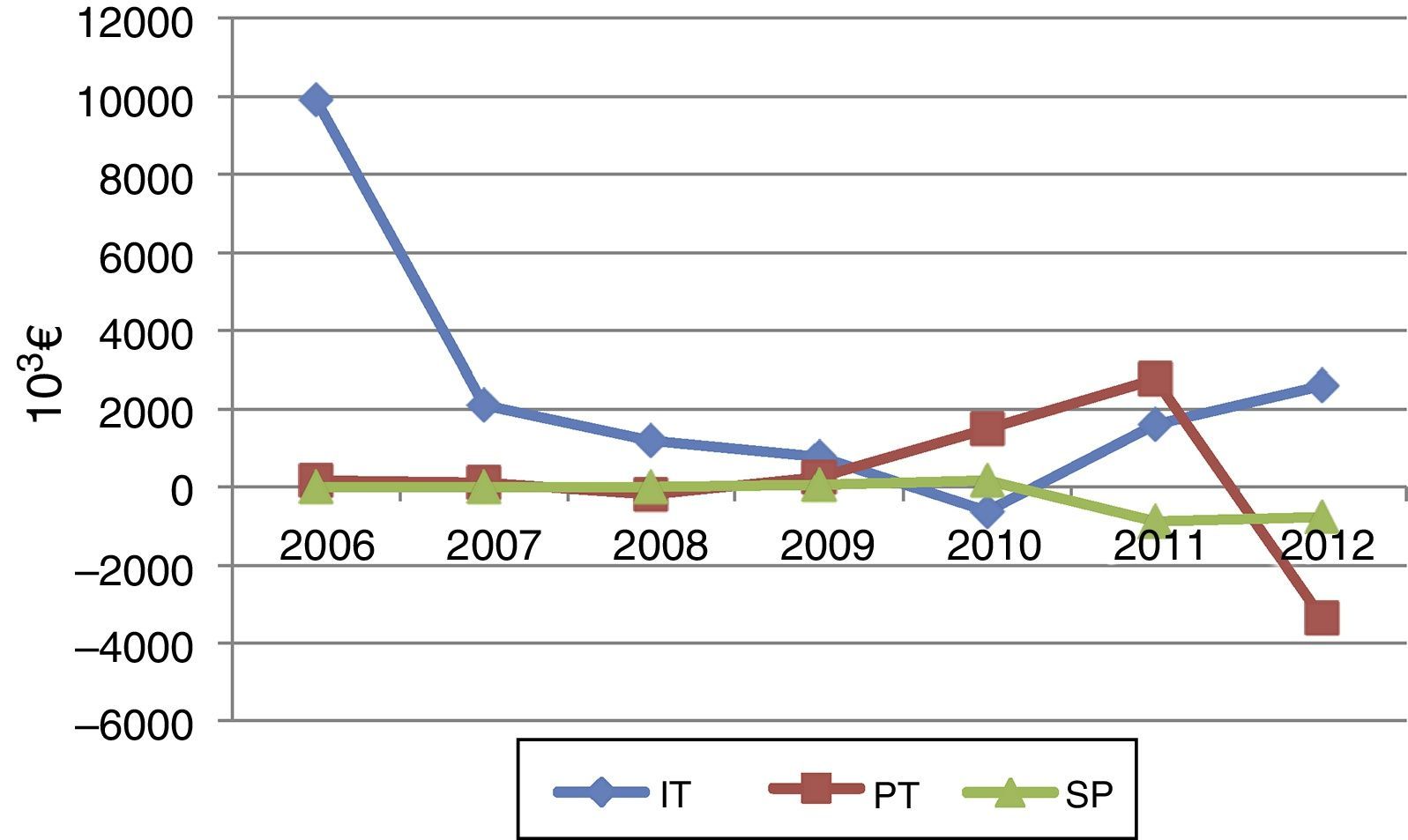

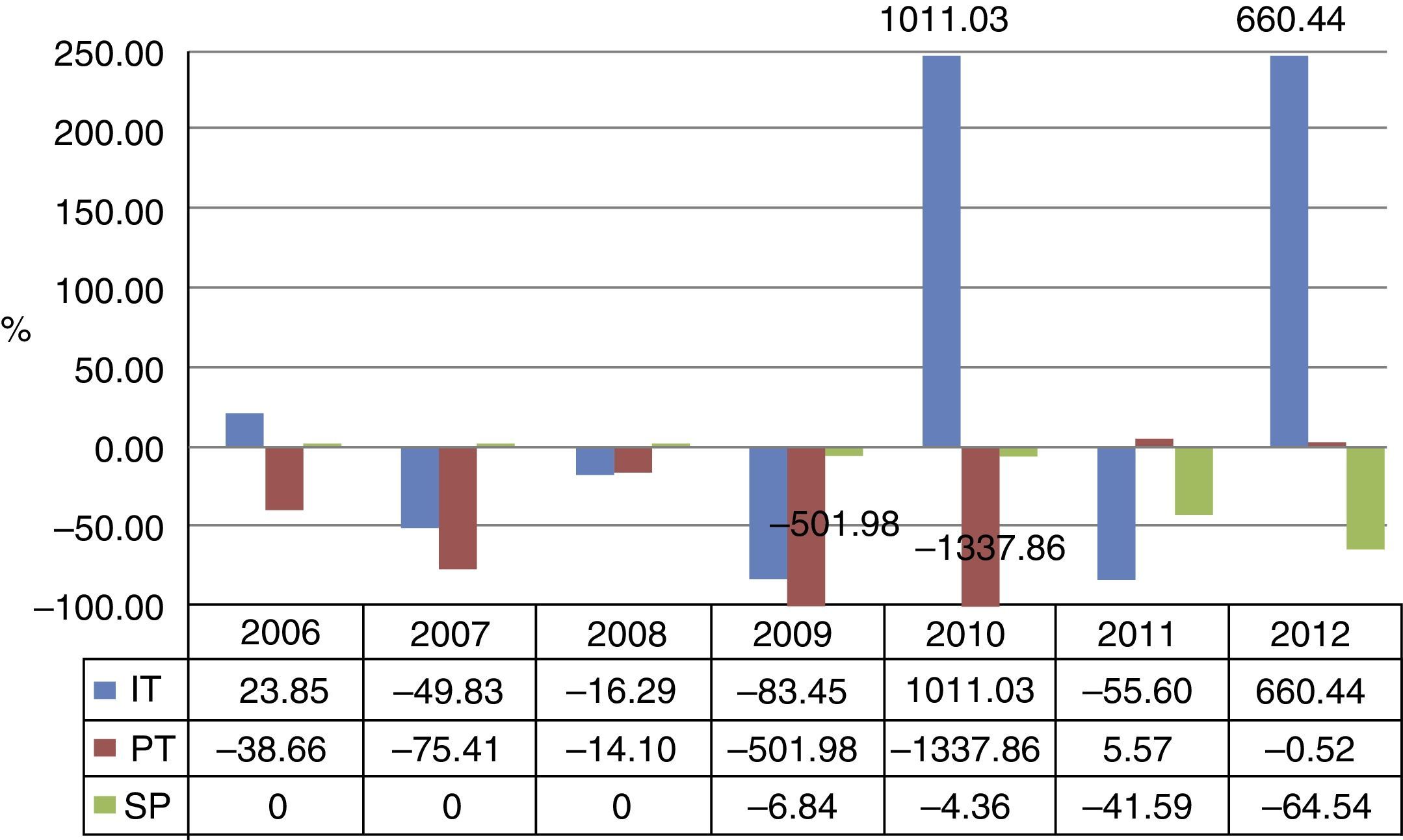

Fig. 5 presents the evolution of adjustments, in absolute amounts, of “other accounts payable”, and Fig. 6 displays to this category the relative weight on the total cash-accrual adjustments.

In Italy the amount of the adjustments in this category evidenced huge oscillations, with peaks in 2006, 2007, 2010 and 2012 and the lowest amounts in 2008 and 2011. In Portugal the amounts of these adjustments were relatively stable and around zero along the analysed period, except in 2010. Spain started disclosing this type of adjustments only after 2009, reaching a very significant high amount in 2012. As in the previous category, since other accounts payable should be already recognised under accrual basis (see Table 4), the amounts disclosed might relate to corrections that had been made, since they concern, as explained, to tax reimbursements.

Regardless the sign of the impact on the deficits, this category shows the highest weights on the total of cash-accrual adjustments in Portugal generally up to 2010, when it reaches 1.338% approximately, being compensated by other categories as showed in Fig. 6. From that year the weights decrease abruptly to approximate zero. Italy shows very high weights in 2012 and especially in 2010 (a bit more than 1.000%). In Spain, the weights start increasing from 2011.

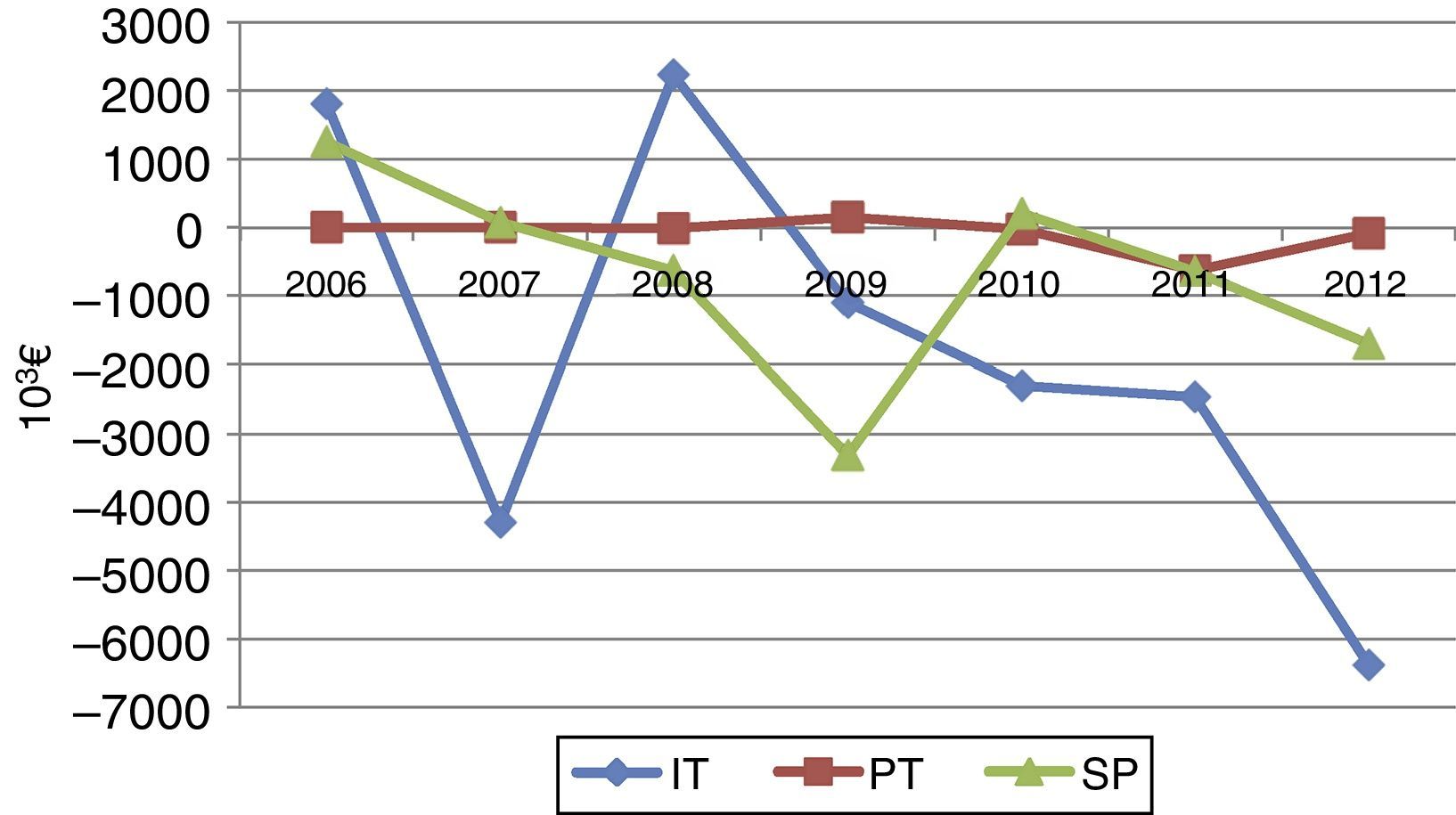

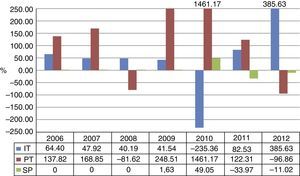

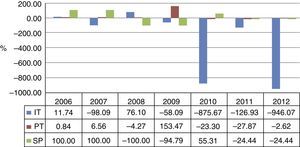

At last, Figs. 7 and 8 relate to “interest paid/accrued”, supporting this category evolution along the years analysed, and its weight in the cash-accrual adjustments as a whole, respectively. This type of adjustments is, as stated in the respective Inventories, made by the three countries.

The Italian figures evolution demonstrates great oscillations in this category of cash-accrual adjustments and alternate impacts on the deficits, between 2006 and 2009. From this year the amounts increase up to the highest negative impact in 2012. In Portugal the amounts of this adjustment category show stability around zero, except in 2009 (positive impact) and 2011 (negative impact). This category is the only one reported by Spain between 2006 and 2008, having positive impact on the budgetary balances (increasing the surplus or decreasing the deficit) in 2006, 2007 and 2010, and negative impact (increasing deficits) in the other years. The highest amount is reached in 2009.

In Portugal this category does not have significant weights in the cash-accrual adjustments as a whole, except in 2009, when it goes over 150% of the adjustments total. In Italy, the percentages are particularly striking in 2010 and 2012, reaching 876% and 946% respectively. In Spain, the percentages start to decrease significantly from 2010, since other categories of cash-accrual adjustment start to be made, hence included in the total, implying a considerable decrease in the relative weight of those concerning “interest paid/accrued”.

This analysis per category shows that “other accounts receivable” and “other accounts payable” represent the most material figures relating to the total of cash-accrual adjustments, which is expectable given that adjustments related to these categories are a direct consequence of the fact that GA ‘working balance’ is still cash-based. As to “other accounts receivable”, one must not forget that, in these illustrative cases, taxes and social contributions have been included in this adjustment category; as to “other accounts payable”, Spain also includes taxes adjustments in this category. Consequently, the amount of cash-accrual adjustments as a whole (Fig. 2) is greatly influenced by adjustments related to taxes and social contributions (included in Fig. 3), which therefore become a critical issue due the great diversity in treatment, as the Inventories describe.

In summary, we can state that, the great materiality above evidenced for the analysed cash-accrual adjustments when translating data from GA into NA, is consistent with one crucial issue raised in the literature review: GA systems, namely budgetary reporting systems, as they currently are, are not able to meet ESA requirements. Consequently, while standardised procedures to convert cash-based (GA) into accrual-based (NA) data are not developed, NA outputs are neither reliable nor comparable between EU countries.

5ConclusionsThe literature review identifies main differences between GA and NA, highlighting those concerning recognition criteria. These relate to the fact that NA data for the General Government Sector are obtained from GA systems, namely from budgetary accounting systems, still cash or modified cash-based in most countries. This leads to the need of making adjustments when transforming data from GA into NA, since the latter is already under an accrual basis regime, although considering some flexibility regarding taxes and social contributions.

Following a descriptive methodology, this paper used empirical data from three countries – Portugal, Spain and Italy, representative of the southern Continental European accounting perspective, all using cash basis budgetary reporting, nowadays struggling to accomplish with the EU convergence criteria. They were selected as illustrative examples of a problem that is common to all countries still reporting in a cash basis within the GA system, especially using cash or modified cash in the budgetary accounting system. Consequently, these countries are good examples to analyse diversity and materiality of the GA-NA accounting basis adjustments, as their reporting authorities might be more tempted to use those adjustments for some accounting management, questioning the reliability of the NA aggregates (namely the deficit) finally reported.

Regarding the analysis of diversity, the main cash-accrual adjustments were identified and compared according to the categories described in the countries’ Inventories of Sources and Methods. It was demonstrated that each country discloses different cash-accrual adjustments as well as apply different treatment procedures to convert GA into NA data. Moreover, it was also observed that these countries, while describing some adjustments in their Inventories, display them in a different way in the EDP reporting Tables, namely Table 2A, concerning Central Government data, the focus of this analysis – the Spanish case is particularly interesting to this issue.

The study therefore demonstrates that diversity is a relevant issue, as GA-NA cash-accrual adjustments are very dissimilar between countries and within each of the categories analysed. Consequently, reliability and comparability of the deficits reported in NA raise doubts about the assessment of the convergence criteria accomplishment.

In what respects materiality of those adjustments, the impact on each country's deficit/surplus was analysed using recent available data for Central Government. Findings show that cash-accrual adjustments as a whole are more significant in the Italian and Portuguese cases, where GA is still essentially cash-based, although with different evolutions along the years analysed, increasing mainly in the last two years. In Spain, the increase in the last two years is more evident, because this country only displays some cash-accrual adjustments categories as from 2009 onwards, yet mentioning accrual basis for the ‘working balance’ reporting (from GA). Materiality shows distinct situations – before and after the year 2009 – being overall much more evident in the last two years regarding Portugal, which might be related to a greatest supervision these countries were submitted to, due to the financial pressure they have undergone.

The most noteworthy categories are “other accounts receivable” and “other accounts payable”, which include “taxes and social contributions” adjustments for Italy and also some tax adjustments for Spain from 2009.

All in all, this analysis evidences that cash-accrual adjustments are diverse and material when transforming GA data into NA data, questioning whether GA systems, namely cash-based budgetary systems, are adequate to meet ESA requirements regarding accrual-based figures, according to which the convergence criteria are assessed. The findings of the empirical study confirm a relevant issue raised by several authors in the literature review, highlighting that GA systems need to be prepared and reported in accrual basis, including budgetary systems, in order to provide accurate data to evaluate final deficits/surpluses among the EU member-States.

Additionally, the analysis points out to the need of a convergence approach between GA and NA systems (as the one in the IPSASB's proposal (IPSASB, 2012), whenever possible, namely concerning the accounting basis, in order to avoid adjustments that present, as the illustrative cases evidence, great diversity in their accounting treatment as well as great materiality compared to the final deficits. This convergence would be an important step, together with standardised procedures to convert cash-based (GA) into accrual-based (NA) data, to improve comparability and reliability of the final figures reported in NA.

In summary, this study points to the importance that GA across countries moves from cash to accrual-based systems, namely in what concerns budgets and budgetary accounting and reporting.

Moreover, it highlights that, adding to the materiality of the adjustments, in countries where GA still uses a cash or modified cash budgetary system simultaneously with an accrual-based financial system, the procedures for the adjustments are diverse, as countries state in the Inventories. Indeed, the EDP Consolidated Inventory of Source and Methods each country discloses, explains particular accounting treatments and procedures, evidencing a great diversity of situations, which represents an obstacle to reach reliable, accurate and comparable NA data, used to sustain EU member-States’ financial decisions. Additionally, evidence was found that the procedures disclosed are not sometimes applied, as data displayed in EDP Notifications demonstrate when comparing with the Inventories statements.

Therefore, the need of a framework of standardised procedures is, in our viewpoint, imperative and a crucial step to increase the reliability of informative outputs, namely deficit reporting, for both micro and macro governmental accounting purposes.

An interesting extension of this research would pass by assessing the effects of changes brought by ESA2010 new rules and their implications on the GA-NA accounting basis adjustments.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The most recent version of the UN System of National Accounts was approved in 2008, implying a subsequent revision of the ESA. ESA2010 based on SNA2008 will be in practice in European countries from September 2014.

In fact, budgetary reporting is cash based. However regarding the budgetary execution, countries like Portugal and Italy use commitments recognition. So, when referring to the budgetary system as a whole, modified cash basis is mentioned, in spite of cash-based budgetary reporting.

In Portugal, Spain and Italy, reliability of Government Financial Statistics gathered by the National Accounts are perhaps even more important than in other countries. In the period considered for analysis, these countries were not fulfilling with the convergence criteria within the EU and/or were at the edge of default, as it came to happen: Portugal is under external financial support since 2011 and Spain and Italy are struggling with serious economic conditions (high levels of public debt and deficits) that have led to austerity policies as those implemented in Portugal under the agreement with the creditors.

United Nations, World Bank, OECD, International Monetary Fund, European Commission (2009), System of National Accounts 2008, New York.

Council Regulation n° 448/98; Commission Regulation n° 1500/2000; Parliament and Council Regulation n° 2516/2000; Commission Regulation n° 995/2001; Parliament and Council Regulation n° 2258/2002; Commission Regulation n° 113/2002; Parliament and Council Regulation n° 549/2013.

This ‘…is not a separate Accounting Standard made by the AASB. Instead, it is a representation of AASB 1049 (October 2007) as amended by other Accounting Standards’. It ‘…applies to annual reporting periods beginning on or after 1 July 2012 but before 1 January 2013. It takes into account amendments up to and including 17 December 2012 and was prepared on 28 February 2013 by the staff of the Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB)’ (AASB, 2013, p. 5).

EDP Consolidated Inventory of Sources and Methods – available to all EU member-States at http://ec.europa.eu/Eurostat.

According to the rules of ESA Manual on Government Deficit and Debt, it is necessary to analyse whether State-owned corporations are profitable in order to decide whether it is expectable that GGS may obtain future income (financial transaction – without impact on deficit/surplus) or whether a capital injection was made to cover accumulated losses (capital transfer – with impact on the deficit/surplus.

Reporting of Government Deficit and Debt Levels that each EU member-State discloses both in April – 1st Notification, and October – 2nd Notification, available in http://ec.europa.eu/Eurostat. According to the EDP requirements, the EU member-States are obliged to prepare the Reporting of Government Deficit and Debt Levels twice a year: 1st Notification in April (N), covering planned data (year N), estimated data (year N−1), half finalised data (year N−2) and final data (years N−3 and N−4); 2nd Notification in October (N), only dissimilar regarding year N−1 data, which are already half-finalised.

During the period of analysis in this paper (2006–2012) no other Inventories were published regarding the three countries. New Inventories were recently published by Italy and Spain in December 2013, as well as by Portugal in March 2014. Still, they do not show any relevant changes to this study.

In Table 2 these agencies are entities out of the subsector State, hence included in the other referred groups of entities.

According to Table 6, in the EDP Table 2A Italy displays “taxes and social contributions” together with “other accounts receivable”. For comparability reasons these two categories of adjustments have to be analysed together for the other countries too.