This paper aims to analyze the impact of auditor tenure on audit quality. The research is motivated by the absence of consensus in published works, and by the scarcity of studies carried out on non-profit organizations. Using a sample of 254 audits carried out between 2003 and 2010 on Spanish state-owned foundations, we find that, although foundation audit quality decreases as tenure length increases, this quality loss does not become apparent until the sixth year of the foundation–auditor relationship, after an initial five years of improvement in quality. The empirical evidence is important for regulators and financial statement users, given that it suggests the need for the introduction of tenure-reducing measures which, at the same time, also ensure a minimum tenure period.

Este trabajo analiza el impacto de la permanencia del auditor sobre la calidad de la auditoría en las entidades no lucrativas. Esta investigación está motivada por la ausencia de consenso en la literatura sobre esta cuestión y la escasez de estudios realizados en el sector de las entidades no lucrativas. Utilizando una muestra de 254 auditorías llevadas a cabo para el período 2003–2010 sobre fundaciones públicas estatales, observamos que, si bien la calidad de la auditoría de las fundaciones disminuye a medida que la permanencia del auditor aumenta, esta pérdida de calidad no se manifiesta hasta el sexto año de la relación fundación–auditor, ya que en los cinco primeros años la calidad aumenta. La evidencia empírica de esta relación tiene importantes implicaciones para los legisladores y los usuarios ya que sugiere la necesidad de introducir medidas que limiten la duración de la misma y, al mismo tiempo, aseguren una duración mínima.

Over the last few decades the relationship between auditor tenure and audit quality has been constantly debated. Even when prior research has been widespread and not completely definitive (Knechel & Vanstraelen, 2007, 113), most of it has involved in the for-profit sector, specifically publicly traded corporations. However, there has been little research done into the effect of the auditor on audit quality in non-profit organizations and that which has been done, as will be shown in the following section, has come out of research into other matters.

This study provides fresh empirical evidence which adds to the debate as it examines the effect of auditor tenure on audit quality in a single sector – non-profit making – where there is hardly any empirical evidence about this relationship.

This analysis is particularly relevant at the present time since governments are being forced by the economic recession to re-structure and rationalize a public sector which has ballooned over the last few decades with the creation of non-profit organizations to undertake certain public functions (Lohmann, 2007). Such organizations must convince the general public that their policies and systems are the right ones to guarantee appropriate management of the resources provided by taxpayers for them to carry out the activities for which they were set up (Greenlee, Fischer, Gordon, & Keating, 2007).

An audit is an instrument which inspires confidence in both external users of financial data concerning these organizations (beneficiaries, public bodies, donors) and internal users – mainly financial directors (Bellostas, Brusca, & Moneva, 2006). This is especially true when the audit opinion is unqualified.

The kind of audit opinion given not only suggests that the organization is complying with accounting regulations and is concerned about its financial management; it also becomes a major factor in identifying or preventing fraudulent activity (Bell & Zimmerman, 2007).

Audit report opinions are, nevertheless, affected by different factors which have been dealt with in a number of papers (González-Díaz, García, & López, 2013; Gosman, 1973; Ireland, 2003; Keasey, Watson, & Wynarczyk, 1988; Krishnan, Krishnan, & Stephens, 1996). One factor is auditor tenure.

The aim of this paper is to analyze how tenure affects audit quality in foundations. Quality is defined from the viewpoint of external users of the financial statements as the likelihood that an auditor will submit a qualified opinion. A sample of 254 audits carried out between 2003 and 2010 was used, representing 46 different foundations. Several logistic regression models were calculated to measure in different ways the effect of auditor tenure on audit quality.

The results show that, although audit quality diminishes as the period of auditor tenure increases, this loss of quality does not become apparent until the sixth year of the foundation–auditor relationship. In fact it improves over the first five years. The empirical evidence of this relationship is important for public auditing given that it highlights the need for the introduction of tenure-reducing measures which, at the same time, also ensure a minimum tenure period.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: The first section reviews relevant literature regarding audit quality and auditor tenure. The second section explains regulations concerning foundation audits and the hypothesis behind the research. The third section outlines the study's methodology. Results follow in the fourth section and, finally, conclusions.

2Prior researchDeAngelo (1981) defines audit quality as the probability of an auditor discovering errors in a client's finances and then bringing these errors to light in the audit report. Audit quality, therefore, depends on auditor competence and independence.

Competence is associated with an auditor's professional skills and independence may be real (the auditor's unbiased or objective attitude), or just appear to be so (different user perception of independence). Some literature on the subject of audit quality considers that the auditor is able to separate both features, while other authors assume them to be linked. Thus, if an auditor is competent, the more likely they are to be independent (Richard, 2006).

Given that it is difficult to come up with a proxy which can assess both auditor competence and independence at the same time (Vanstraelen, 2000, 420), and that the cost of measuring the quality of the auditor's work is highly significant, consumers develop subrogates for audit quality (proxies) which may be correlated to quality (DeAngelo, 1981). Carcello, Hermanson, and Huss (1995) point out some of these which have been used by other authors: litigation against law firms, auditor selection, auditor changes and firm size, nature of auditors’ opinions, pricing of audit services and user perception.

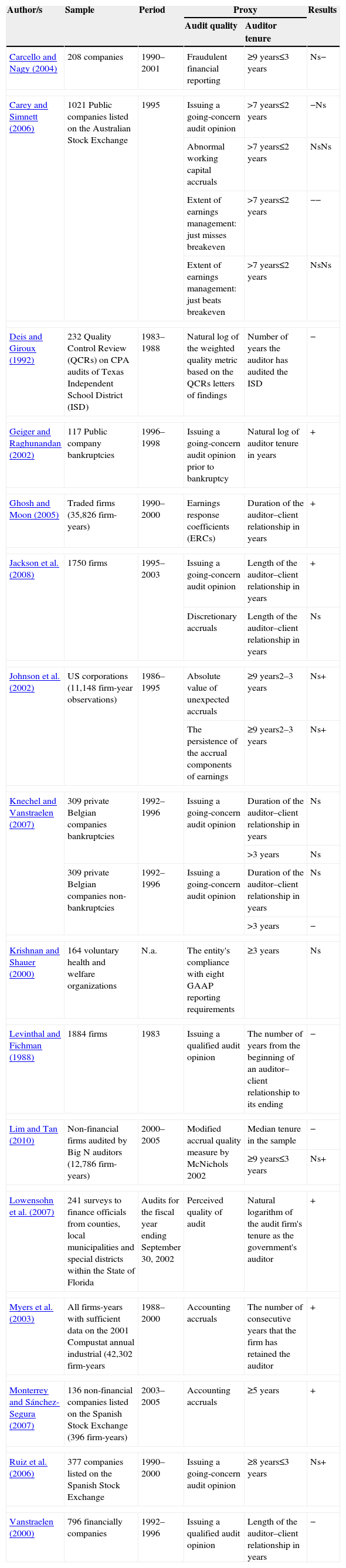

Also, over the last few decades researchers have analyzed determining factors in audit quality as well as the effect of auditor tenure on quality, with a number of studies devoted principally to the latter and undertaken in the private sector – Table 1 summarizes some of the works published in this regard.

Empirical evidence on the relationship between audit quality and auditor tenure.

| Author/s | Sample | Period | Proxy | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audit quality | Auditor tenure | ||||

| Carcello and Nagy (2004) | 208 companies | 1990–2001 | Fraudulent financial reporting | ≥9 years≤3 years | Ns− |

| Carey and Simnett (2006) | 1021 Public companies listed on the Australian Stock Exchange | 1995 | Issuing a going-concern audit opinion | >7 years≤2 years | −Ns |

| Abnormal working capital accruals | >7 years≤2 years | NsNs | |||

| Extent of earnings management: just misses breakeven | >7 years≤2 years | −− | |||

| Extent of earnings management: just beats breakeven | >7 years≤2 years | NsNs | |||

| Deis and Giroux (1992) | 232 Quality Control Review (QCRs) on CPA audits of Texas Independent School District (ISD) | 1983–1988 | Natural log of the weighted quality metric based on the QCRs letters of findings | Number of years the auditor has audited the ISD | − |

| Geiger and Raghunandan (2002) | 117 Public company bankruptcies | 1996–1998 | Issuing a going-concern audit opinion prior to bankruptcy | Natural log of auditor tenure in years | + |

| Ghosh and Moon (2005) | Traded firms (35,826 firm-years) | 1990–2000 | Earnings response coefficients (ERCs) | Duration of the auditor–client relationship in years | + |

| Jackson et al. (2008) | 1750 firms | 1995–2003 | Issuing a going-concern audit opinion | Length of the auditor–client relationship in years | + |

| Discretionary accruals | Length of the auditor–client relationship in years | Ns | |||

| Johnson et al. (2002) | US corporations (11,148 firm-year observations) | 1986–1995 | Absolute value of unexpected accruals | ≥9 years2–3 years | Ns+ |

| The persistence of the accrual components of earnings | ≥9 years2–3 years | Ns+ | |||

| Knechel and Vanstraelen (2007) | 309 private Belgian companies bankruptcies | 1992–1996 | Issuing a going-concern audit opinion | Duration of the auditor–client relationship in years | Ns |

| >3 years | Ns | ||||

| 309 private Belgian companies non-bankruptcies | 1992–1996 | Issuing a going-concern audit opinion | Duration of the auditor–client relationship in years | Ns | |

| >3 years | − | ||||

| Krishnan and Shauer (2000) | 164 voluntary health and welfare organizations | N.a. | The entity's compliance with eight GAAP reporting requirements | ≥3 years | Ns |

| Levinthal and Fichman (1988) | 1884 firms | 1983 | Issuing a qualified audit opinion | The number of years from the beginning of an auditor–client relationship to its ending | − |

| Lim and Tan (2010) | Non-financial firms audited by Big N auditors (12,786 firm-years) | 2000–2005 | Modified accrual quality measure by McNichols 2002 | Median tenure in the sample | − |

| ≥9 years≤3 years | Ns+ | ||||

| Lowensohn et al. (2007) | 241 surveys to finance officials from counties, local municipalities and special districts within the State of Florida | Audits for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2002 | Perceived quality of audit | Natural logarithm of the audit firm's tenure as the government's auditor | + |

| Myers et al. (2003) | All firms-years with sufficient data on the 2001 Compustat annual industrial (42,302 firm-years | 1988–2000 | Accounting accruals | The number of consecutive years that the firm has retained the auditor | + |

| Monterrey and Sánchez-Segura (2007) | 136 non-financial companies listed on the Spanish Stock Exchange (396 firm-years) | 2003–2005 | Accounting accruals | ≥5 years | + |

| Ruiz et al. (2006) | 377 companies listed on the Spanish Stock Exchange | 1990–2000 | Issuing a going-concern audit opinion | ≥8 years≤3 years | Ns+ |

| Vanstraelen (2000) | 796 financially companies | 1992–1996 | Issuing a qualified audit opinion | Length of the auditor–client relationship in years | − |

Ns: not significant; Na: not available.

Specialized literature on the subject has pointed out the lack of consensus concerning the audit quality–auditor tenure relation (Vanstraelen, 2000) because auditor tenure can have a positive or negative impact on the two main determinants of audit quality: auditor competence and auditor independence.

Geiger and Raghunandan (2002), Myers, Myers, and Omer (2003), Ghosh and Moon (2005), Knechel and Vanstraelen (2007) and Jackson, Moldrich, and Roebuck (2008) have shown that audit quality improves with auditor tenure. However, Levinthal and Fichman (1988) and Deis and Giroux (1992) show just the opposite. By measuring tenure as the number of years an auditor has audited a company, these studies consider the audit quality–auditor tenure relation to be linear.

Ruiz, Gómez, and Carrera (2006) suggest that divergences from an empirical point of view may be due to the fact that audit quality does not vary in a linear way over the duration of the contract and that it may change depending on the duration of client/auditor relationship.

Long auditor tenure may increase competence because the auditor's client-specific knowledge increases over the years (St. Pierre and Anderson, 1984). This will allow them to improve the quality of their auditing but it could also reduce their degree of independence in the sense that a long auditor–client relationship may make the auditor financially reliant on the client (Ruiz et al., 2006) and bring about such a close relationship (Whittington, Grout, & Jewitt, 1995) that unbiased assessment is compromised (Shockley, 1981) by lack of both innovation and procedural rigour (Schockley, 1982).

Johnson, Khurana, and Reynolds (2002) claim that specific client knowledge gained over the years could entail a reduction in auditor effort, yet this does not necessarily involve a threat to the quality of the work.

Short auditor tenure could negatively affect competence because auditors’ client knowledge is less over the first few years and they need time to get used to their clients’ activity and accounting procedures (Carcello & Nagy, 2004). Their independence could also be compromised since they need to keep new clients in order to recover their initial client-specific investment, which cannot be transferred to other contracts (Ruiz et al., 2006).

Industry specialization, however, can improve both competence and independence, leading to higher audit quality since auditors know their sector far better than non-specialist firms and can audit new clients more easily. Also, the higher a firm's reputation in its sector, the more independence it seems to have (Lim & Tan, 2010).

Vanstraelen (2000), Johnson et al. (2002), Carcello and Nagy (2004), Carey and Simnett (2006), Ruiz et al. (2006), and Monterrey and Sánchez-Segura (2007) acknowledge the non-linear nature of the relation by attempting to show that the duration of an auditor's contract can influence audit quality.

Vanstraelen (2000) in particular points out that auditor performance is different in the first two and in the final years of tenure. She claims that the likelihood of issuing a qualified opinion is greater in the final year than in the first two because the auditor knows that their contract will not be renewed and that the current audit will be the last.

Johnson et al. (2002), looking at a context in which auditor rotation is not compulsory, provide evidence that financial reporting quality is associated with short audit-firm tenures. Ruiz et al. (2006) confirm the fact that audit quality grows over the first few years but then does not drop away in long tenures. Carcello and Nagy (2004, 55) point out that “fraudulent financial reporting is more likely to occur in the first three years of the auditor–client relationship” although they fail to show that this happens with longer tenures.

Monterrey and Sánchez-Segura (2007) show that when the auditor–client relationship has lasted over 5 years the benefits of such familiarity become obvious, as the auditor has got to know the client well. The study suggests that rotation regulations should be aimed at ensuring long tenure, as constant changes do not bring about greater accounting quality.

On the other hand, Carey and Simnett (2006, 674) claim that the longer the audit partner tenure the lower the quality of the audit, when quality is measured in terms of the auditor's propensity to issue a going-concern audit opinion and just meeting (missing) earnings benchmarks.

By analyzing these previous studies it is clear that their empirical results are not conclusive. Ewelt-Knauer, Gold, and Pott (2012, 2013, 35) suggest that the positive or negative effects of the client/auditor association depend on what research method is used as well as the proxy chosen to measure audit quality. They also point out that, by analyzing stakeholders, “regulators take a stance in favour of rotation, arguing that rotation provides an opportunity to overcome problems caused by (excessive) tenure. At the other extreme, audit firms are critical and point to a loss of knowledge and expertise potentially caused by rotation. The views of audit clients and shareholders overall appear to be relatively mixed”.

The audit quality–auditor tenure relation has barely been researched in the public and non-profit sectors. In the public sector Deis and Giroux (1992) look at what determines audit quality in independent school districts in Texas and Lowensohn, Johnson, Elder, and Davies (2007) study the relation between audit quality perceived by 241 Florida local government finance directors and certain audit/auditor attributes. The results of these studies are contradictory with the quality–tenure results being negative in the former and positive in the latter.

In the non-profit sector Krishnan and Shauer (2000) examine the relation between quality auditing and auditor tenure, although the main aim of their study is the relation between auditor size and the audit quality of 164 voluntary health and welfare organizations in south-eastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey. Their results show zero impact on audit quality.

Other works concerning the non-profit sector include a study of auditor tenure being a determining factor, not in audit quality but in audit-firm fees (Ellis & Booker, 2011; Vermeer, Raghunandan, & Forgione, 2009) or information on internal control weaknesses (López & Peters, 2010). In this context, the aim of this study is to provide evidence from the non-profit sector that may assist the debate about whether or not to establish tenure limits.

3Auditing of state-owned foundationsFoundations are organizations which collaborate with the state in order to achieve aims of general interest (IGAE, 2010). To be of general interest, one or both of the following pre-requisites are necessary:

- •

They should be created through a direct or indirect majority contribution from the General State Administration, its public organisms or other entities belonging to the public sector.

- •

More than 50 percent of their fixed assets should comprise goods or rights which have been provided by or transferred from the above-mentioned public entities.

External audits of these organizations are regulated by the Law 50/2002 on Foundations, which came into effect on 1 January 2003, and by the Royal Decree 1337/2005, which encompasses regulations referring to state-owned foundations. The General Budgetary Act (GBA) 47/2003 also includes regulations governing foundations.

The Foundations Act designates the “Intervención General del Estado” (IGAE) (General State Comptroller) as the auditor of foundations. The IGAE is required to audit these organizations over two consecutive years when at least 2 of the following situations arise 2 years in a row:

- •

Assets amount to over 2,400,000 Euros.

- •

Annual revenues amount to over 2,400,000 Euros.

- •

The foundation has over 50 employees.

Establishing a minimum related to assets, state subsidies, income and costs or the number of employees is a general criterion applied in most countries to decide whether or not a non-profit organization should be audited or not (Kitching, 2009; Tate, 2007). It is unusual for compulsory audits to be determined solely according to the nature of the foundation (EFC, 2011).

Foundations which come into the IGAE compulsory-audit category are considered large. Small and medium-sized foundations are not all legally required to be audited and yet some voluntarily request private firm audit.

Up until now types of foundation auditors have been analyzed, but not the length of time their relationship lasts. The IGAE is required to carry out annual external audits on large foundations, which entails the public auditor having an indefinite relationship with the foundation unless it either ceases to exist or is no longer considered “large”. As far as private auditors are concerned, Spanish audit law states that, when audits are compulsory, private auditors cannot be contracted by any single organization for less than three years or more than nine. When audits are voluntary, however, as is the case in this study, these restrictions are not applied, which means that a foundation that chooses to be audited annually can maintain an indefinite relationship with an auditor. It is, therefore, an environment without mandatory auditor rotation.

The “Tribunal de Cuentas”, as the supreme auditing and financial management body of the Spanish state and of the public sector, may undertake control activity in state-owned foundations. Since its beginnings in 1982, it has been involved in scrutinizing and checking public accounts, including the state foundation sector, where external audits carried out by the IGAE figure prominently.

Also, the “Tribunal de Cuentas” annual programme may include foundation auditing. Between 2003 and 2010 this institution issued 9 reports on the auditing of state-owned foundations. The reports deal with a variety of auditing objectives, from financial and legal audits to management efficiency and compliance with hiring requirements.

The scarcity of academic studies on the non-profit sector prevents us from reaching any firm conclusions about the audit quality–auditor tenure relation. However, diverse empirical evidence in the private sector, plus the legal framework for foundations in Spain, leads us to the following hypothesis.Hypothesis There is an association between audit quality and auditor tenure.

The main data analyzed in this study was obtained from the Inventory of State/Public Sector Organizations (INVESPE) – the main source and a software application which has been prepared and updated by the IGAE – as well as the Declaration of the General Statement of State Accounts, and the financial reports on state foundations from 2003 to 2010. The study started in 2003, when the Foundations Law (which establishes who exactly should audit foundations) came into effect. It concluded in 2010, the year with the latest available data. Prior to the Foundations Law, Spanish legislation did not specify either who should audit foundations or which financial reporting regulations should be applied (González, García, & López, 2011).

Of the 256 audits carried out over this period, 2 have been excluded as one of them contains an adverse opinion and the other is a disclaimer. The final dataset used for this study includes 254 audits with positive or qualified opinions.

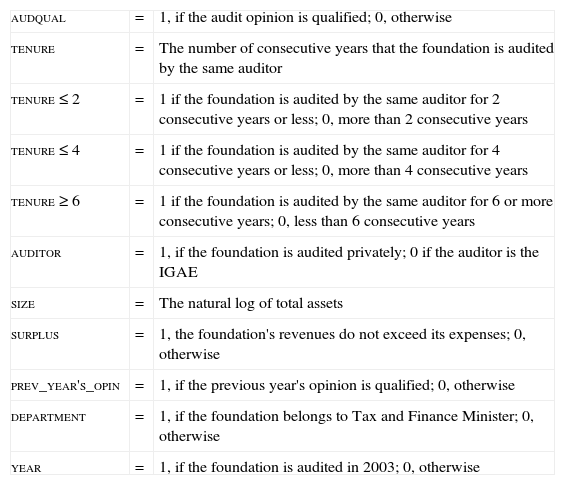

4.2MethodologyThe effect of auditor tenure on audit quality in foundations was examined via the estimation of logistic regression models in which audit quality (audqual) is the dependent variable. The independent variable is auditor tenure (aud_tenure) and control variables are: type of auditor (auditor), size (size), previous year's opinion (prev_year's_opin), the foundations’ revenue exceeds its expenses (surplus), the sector (department) and the year (year).

4.2.1Dependent variableAudqual is a dummy variable which takes the values 1 and 0 depending on whether the report is qualified (1) or unqualified (0).

Most of the studies which were examined use only one proxy to measure audit quality, except Johnson et al. (2002) and Jackson et al. (2008), which use two, and Carey and Simnett (2006) which uses four.

In this study audit quality has been measured from the point of view of external users of financial statements as the likelihood that an auditor will issue a qualified opinion – the proxy used by Levinthal and Fichman (1988) and Vanstraelen (2000). When an auditor issues an unclean audit report it means they are able to objectively assess business results and resist client pressure to issue a clean opinion (DeFond, Raghunandan, & Subramanyam, 2002, 1248–1249). This suggests that there is a positive correlation between the issuing of a qualified opinion and the level of auditor competence and independence.

Moreover, this proxy was chosen due to the fact that access to financial information from these organizations is very difficult given that they fail to comply with article 136 of the General Budgetary Act which requires their annual accounts to be published in the Official Gazette. Moreover, not all of those who have published their annual accounts in the Gazette have included the audit report, a key document for identifying and classifying qualified opinions that can be used as audit quality proxies. It is hoped, nevertheless, that the new Law, 19/2013 on transparency, information access and good government, which requires foundations to publish their annual accounts and audit reports, will reinforce their commitment to publish in the Gazette.

4.2.2Independent variableTenure is measured in two ways: as a continuous or as a dummy variable. In the former case, tenure is calculated as the number of consecutive years a foundation has been audited by the same auditor (Ellis & Booker, 2011; Geiger & Raghunandan, 2002; Ghosh & Moon, 2005; Gul, Jaggi, & Krishnan, 2007; Lowensohn et al., 2007; Myers et al., 2003). The year 1999 was chosen as the starting point because the foundations financial reports became available then. Using this proxy entails regarding the audit quality–auditor tenure relation as linear; in other words, the longer the tenure the greater or lesser the audit quality.

For the dummy variable three measurements, obtained by calculating tenure quartiles (Q1=2; Q2=4; Q3=6) for every sample, were used. The three measurements, therefore, are defined as tenure≤2 years, tenure≤4 years and tenure≥6 years.

It is usual to bear in mind the regulations each country has concerning the length of auditor tenure in order to define the tenure variable when audit quality does not vary in a linear way for the duration of the contract. In this sense, the United States and some EU countries regulate tenure (Vanstraelen, 2000) by setting minimum and maximum periods, which some studies have used as a reference for defining short, medium and long tenure (Carcello & Nagy, 2004; Gunny et al., 2007; Ruiz et al., 2006), or simply as a means of specifying minimum tenure, at the end of which the client and auditor may put an end to their relationship (Knechel & Vanstraelen, 2007).

The study has been unable to consider current tenure legislation in Spain because, as was pointed out, there is no upper or lower tenure limit for auditors of state foundations. The criteria used to define dummy variables was to categorize the continuous tenure variable as a dummy variable, according to the limits established by the quartiles as proposed by Miján (2002, 392) in order to detect the independent effects that may exist at each level and, at the same time, bear in mind observation allocation. Lim and Tan (2010), when categorizing auditor tenure, use percentiles as the median and Fitzgerald, Thompson, and Omer (2012) classify auditor tenure into short (1–2 years), medium (3–5 years), and long (6 or more years).

4.2.3Control variablesThe control variables are those which have been identified in previous studies as being possible determining factors in quality audits: auditor, size, opinion from the previous year's report, surplus, sector and year.

External audits of the foundations are carried out by private auditors or by the IGAE, depending on certain conditions. There is a dummy variable (auditor) which takes a value of 1 when the auditors are private and 0 when it is the IGAE. There are also differences of opinion concerning the influence of auditor type on audit quality. Johnson et al. (2002), Ruiz et al. (2006) and Lim and Tan (2010) do not factor in audit type when analysing tenure influence on quality. Yet the research of Vanstraelen (2000), Knechel and Vanstraelen (2007) and Monterrey and Sánchez-Segura (2007) does study its impact whilst making a distinction between the “Big 4” audit firms and the rest. The results are by no means uniform; Vanstraelen (2000) and Knechel and Vanstraelen (2007) find no empirical evidence that auditor type affects quality; Monterrey and Sánchez-Segura (2007), however, conclude that quality improves if the auditor is a large firm and its tenure is less than five years.

This research explores the effect of auditor type on audit quality in a context where auditor type depends on the size of the audited organization, distinguishing between public and private types of auditor rather than between large firms and the rest.

In this sense, existing literature points out relevant differences between public and private auditors. Jakubowski (1995) carried out a study which attempted to ascertain whether the type of auditor – public or private – might or might not affect the number of control weaknesses detected in local governments. The study revealed that state auditors discovered more weaknesses than did private firms. The author considers that state and private auditors view the audit process differently. Whereas the former are under no pressure from their clients (taxpayers), the latter may lose clients (local governments) if the number of qualifications published is particularly high. This would help to explain why state auditors report more weaknesses than both large and small private firms.

In a report commissioned by the GAO (Government Accountability Office, 2007) the President's Council on Integrity and Efficiency reviewed a sample of 208 audits undertaken by state and private auditors on relevant state and local governments and non-profit organizations in 2003. The report concluded that an audit was unacceptable when deficiencies were “so serious that the auditors’ opinion on at least one major programme cannot be relied upon; e.g. no evidence of internal control testing and compliance testing for all or most compliance requirements for one or more major programmes, unreported audit findings, and at least one incorrectly identified major program” – 30.29 percent of the audits reviewed were thus rated and all of these had been conducted by private auditors.

This result may be explained by Jakubowski's thesis, but it could also be true that private auditors fail to devote enough resources for detecting weaknesses in internal control systems in these organizations. In fact, López and Peters (2010) obtained a result which changed the empirical evidence of previous studies. They researched the relationship between opinion type and auditor type by looking at a sample of audit reports pertaining to a set of US cities and counties over the period 2004–2006. They reached the conclusion that the likelihood of detecting internal control issues increases if the auditors are private. They argue that, in the USA, private firms boosted resources for assessing internal control in the audits they carried out.

On the other hand, Dehkordi and Makarem's study (2011) published a year after the one by López and Peters and which examines the effects of auditor type and size on audit quality in Iran, concludes that financial statements audited by the public “Audit Organization” contain fewer discretionary accruals than statements audited by private firms. This suggests that when the public auditor does the audit the quality is higher. Bearing in mind that, with the exception of the López and Peters’ study in 2010, all other work is unanimous, it is to be expected that the sign of the dependent variable-type of auditor relation will be positive.

Size is defined as the natural log of total assets (size). Some studies show that the bigger an organization, the lower the audit quality, since the complexity of its operations demands specific auditor knowledge (Krishnan & Shauer, 2000; O’Keefe, King, & Gaver, 1994). Therefore, a positive sign is predicted.

Previous year's opinion (prev_year's_opin) is defined as a dummy variable which takes the value of 1 when the opinion in the previous year's report was qualified and 0 in the opposite case. This variable has been included in the study since there is empirical proof that shows that the same audit opinion is repeated over time, increasing the probability of receiving a qualified opinion if the previous year's opinion was also qualified (Ireland, 2003; Keasey et al., 1988).

The audit firm may have an incentive to repeatedly qualify audit reports if, having qualified the first one, the company has not decided whether its services will still be required (Ireland, 2003). Also, the type of qualification may cause the qualified opinion to be maintained over several years since a company that receives a qualified opinion brought about by uncertainty the previous year is very likely to get the same opinion in the current year given that uncertainty may extend beyond one year (González et al., 2011; Monroe & Teh, 1993). Therefore, a positive sign is predicted.

This study also includes an indicator of whether the foundation's revenues exceed its expenses (surplus). This is expressed as a dummy variable with a value of 1 when its income is less than its running costs (losses) and 0 in the opposite case. It is defined as a dummy rather than a continuous variable based on work carried out by other authors concerning the non-profit sector (Keating, Fischer, Gordon, & Greenlee, 2005; Petrovits, Shakespeare, & Shih, 2011).

Non-profit organizations may have incentives to minimize their profits. On the one hand, donors and regulating bodies may get the impression that profit contradicts the fundamental purpose of the organization (Trussel, 2003). A study carried out by Calabrese (2011) shows that future contributions of donors are negatively affected when wealth levels are deemed excessive; on the other hand, as profit should be reinvested in the organization and not shared out among partners and employees, it is possible that certain illicit practices such as unwarranted expense claims could take place (Greenlee et al., 2007). It is to be expected that the coefficient sign related to the surplus variable will be positive.

The variable concerning the relationship with particular government departments (department) is also a dummy one and takes the value of 1 when the foundation belongs to the Tax and Finance Department, and 0 in the opposite case.

Empirical evidence obtained from private sector studies (Bamber, Bamber, & Schoderbeck, 1993; Maletta & Wright, 1996) considers that there are reasons to assume that the sector in which a company operates is a variable which can explain opinion type. In the non-profit sector it is argued that some organizations have greater internal control and that the requirements for programmes related to certain types of subsidy or organization are stricter in some sectors than in others, which entail variations in quality. The variable sign is not predicted as previous studies where it has been included have used diverse classifications which are different from that proposed in this study (Keating et al., 2005).

State foundations may be linked according to sectors by means of their “Protectorate”, an umbrella organization whose aim is to guarantee legal and foundation purpose compliance. The Protectorate provides support, initiatives and legal, financial and accounting advice. It comes under the auspices of State Services through different government departments whose responsibilities are more directly related to the foundation purposes (González-Díaz et al., 2013).

The decision to make this a dummy variable was taken because 23.62 percent of the 254 selected foundations report to the Tax and Finance Department and the rest to other departments. Also, a more detailed breakdown could cause statistical inference problems brought about by the smallness of a particular department (Sánchez & Sierra, 2001).

Finally, the year 2003 is included as a control variable (year) since this is when the Foundations Law, requiring the IGAE to audit large foundations, came into force. This variable takes the value of 1 when the foundation was audited in 2003 and 0 in the opposite case.

4.2.4Model specificationThe use of the dependent audqual variable and a significant number of dummy independent and control variables has given rise to logistic regression being used as the analysis methodology (Keasey et al., 1988) in which the regression coefficients estimate the impact of the independent variable on the probability that the type of opinion will be qualified. A positive sign for the coefficient means that a variable increases the probability of a qualified opinion; a negative sign indicates the reverse.

The model can be expressed in this way:

A summary of all variables is included in Table 2.

Description of all variables.

| audqual | = | 1, if the audit opinion is qualified; 0, otherwise |

| tenure | = | The number of consecutive years that the foundation is audited by the same auditor |

| tenure≤2 | = | 1 if the foundation is audited by the same auditor for 2 consecutive years or less; 0, more than 2 consecutive years |

| tenure≤4 | = | 1 if the foundation is audited by the same auditor for 4 consecutive years or less; 0, more than 4 consecutive years |

| tenure≥6 | = | 1 if the foundation is audited by the same auditor for 6 or more consecutive years; 0, less than 6 consecutive years |

| auditor | = | 1, if the foundation is audited privately; 0 if the auditor is the IGAE |

| size | = | The natural log of total assets |

| surplus | = | 1, the foundation's revenues do not exceed its expenses; 0, otherwise |

| prev_year's_opin | = | 1, if the previous year's opinion is qualified; 0, otherwise |

| department | = | 1, if the foundation belongs to Tax and Finance Minister; 0, otherwise |

| year | = | 1, if the foundation is audited in 2003; 0, otherwise |

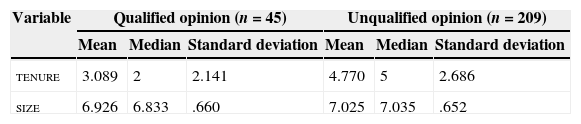

In this section both univariate and multivariate results related to tenure and auditor type are presented along with the remaining control variables.

5.1Descriptive and univariate analysisTable 3 shows the descriptive statistics of the sample. The tenure variable provides a mean value slightly higher than three and a median of two for qualified reports and greater values, for both the mean and the median in unqualified reports. The descriptive statistics of the tenure variables, measured as a dummy variable, show that the greater the time of the auditor–foundation relationship, the lesser the likelihood of qualified reports. Also, 18.97 percent of IGAE reports were qualified, whereas the percentage drops to 15 percent when the auditors were private.

Descriptive Statistics.

| Variable | Qualified opinion (n=45) | Unqualified opinion (n=209) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Standard deviation | Mean | Median | Standard deviation | |

| tenure | 3.089 | 2 | 2.141 | 4.770 | 5 | 2.686 |

| size | 6.926 | 6.833 | .660 | 7.025 | 7.035 | .652 |

| Qualified opinion | Unqualified opinion | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percent | n | Percent | n | Percent | |

| tenure≤2 | ||||||

| Three or more consecutive years | 21 | 11.73 | 158 | 88.27 | 179 | 70.47 |

| Two or less consecutive years | 24 | 32.00 | 51 | 68.00 | 75 | 29.53 |

| tenure≤4 | ||||||

| Five or more consecutive years | 13 | 11.02 | 105 | 88.98 | 118 | 46.46 |

| Four or less consecutive years | 32 | 23.53 | 104 | 76.47 | 136 | 53.54 |

| tenure≥6 | ||||||

| Five or less consecutive years | 38 | 22.22 | 133 | 77.78 | 171 | 67.32 |

| Six or more consecutive years | 7 | 8.43 | 76 | 91.57 | 83 | 32.68 |

| auditor | ||||||

| IGAE | 33 | 18.97 | 141 | 81.03 | 174 | 68.50 |

| Private auditor | 12 | 15.00 | 68 | 85.00 | 80 | 31.50 |

| surplus | ||||||

| Revenues exceed expenses | 27 | 17.76 | 125 | 82.24 | 152 | 59.84 |

| Revenues do not exceed expenses | 18 | 17.65 | 84 | 82.35 | 102 | 40.16 |

| prev_year's_opin | ||||||

| Unqualified opinion | 18 | 8.61 | 191 | 91.39 | 209 | 82.28 |

| Qualified opinion | 27 | 60.00 | 18 | 40.00 | 45 | 17.72 |

| department | ||||||

| Foreign affairs and cooperation | 2 | 15.38 | 11 | 84.62 | 13 | 5.12 |

| Culture | 6 | 20.69 | 23 | 79.31 | 29 | 11.42 |

| Tax and finance | 5 | 8.33 | 55 | 91.67 | 60 | 23.62 |

| Education, science and innovation | 5 | 10.42 | 43 | 89.58 | 48 | 18.90 |

| Public works | 8 | 30.77 | 18 | 69.23 | 26 | 10.24 |

| Industry, tourism and commerce | 3 | 11.11 | 24 | 88.89 | 27 | 10.63 |

| Justice | 3 | 60.00 | 2 | 40.00 | 5 | 1.97 |

| The environment | 1 | 8.33 | 11 | 91.67 | 12 | 4.72 |

| Health and consumer affairs | 8 | 50.00 | 8 | 50.00 | 16 | 6.30 |

| Labour and social services | 4 | 22.22 | 14 | 77.78 | 18 | 7.09 |

| year | ||||||

| 2003 | 7 | 30.43 | 16 | 69.57 | 23 | 9.06 |

| 2004 | 7 | 24.14 | 22 | 75.86 | 29 | 11.42 |

| 2005 | 6 | 21.43 | 22 | 78.57 | 28 | 11.02 |

| 2006 | 7 | 21.21 | 26 | 78.79 | 33 | 12.99 |

| 2007 | 6 | 20.00 | 24 | 80.00 | 30 | 11.81 |

| 2008 | 5 | 15.63 | 27 | 84.38 | 32 | 12.60 |

| 2009 | 3 | 8.33 | 33 | 91.67 | 36 | 14.17 |

| 2010 | 4 | 9.30 | 39 | 90.70 | 43 | 16.93 |

In addition, Table 3 describes the remaining variables used in the study. It can be seen that audit quality could in some way be linked to the previous year's opinion since 60 percent of the foundations that got a qualified opinion had got the same the previous year, as did 91.39 percent of those whose previous year's opinion had been unqualified. Yet it does not appear that revenue earnings greater than expenses affect quality given that the percentage of qualified reports is very similar in the case of both positive (17.76 percent) and negative (17.65 percent) results.

As for foundations’ relationships with government departments, the descriptive data highlights the fact that those organizations that receive fewer qualified reports are those under the auspices of the departments of Education, Science and Innovation (10.42 percent), Environment (8.33 percent), and Tax and Finance (8.33 percent). At the opposite extreme are Justice (60 percent), Health and Consumer Affairs (50 percent) and Public Works (30.77 percent).

The descriptive statistics of the year variable shows that the percentage of qualified opinions decreases steadily from the beginning of the period studied until the end given that 30.43 percent of foundations received a qualified opinion in 2003 and only 9.3 percent in 2010.

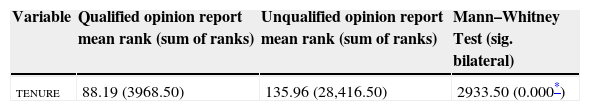

So as to determine possible relations between explanatory variables and opinion type, a univariate study was carried out whereby observations are divided into those with a qualified and those with an unqualified opinion, the aim being to detect any major differences among them (Table 4).

Univariate analysis.

| Variable | Qualified opinion report mean rank (sum of ranks) | Unqualified opinion report mean rank (sum of ranks) | Mann–Whitney Test (sig. bilateral) |

|---|---|---|---|

| tenure | 88.19 (3968.50) | 135.96 (28,416.50) | 2933.50 (0.000*) |

| Variable | Student's t-test | Sig. bilateral |

|---|---|---|

| size | 0.926 | 0.355 |

The results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test suggest that the explanatory variables do not follow a normal pattern, except the size one, which also shows homoscedasticity.

Therefore, the Student's t-test was applied to the size variable, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test to the variable tenure and Pearson's chi-square test to the dummies variables.

It can be seen that auditor tenure (tenure, tenure≤2, tenure≤4 and tenure≥6) is different according to whether the reports were clean or not. And also several control variables (prev_year's_opin and department) behave differently according to opinion type.

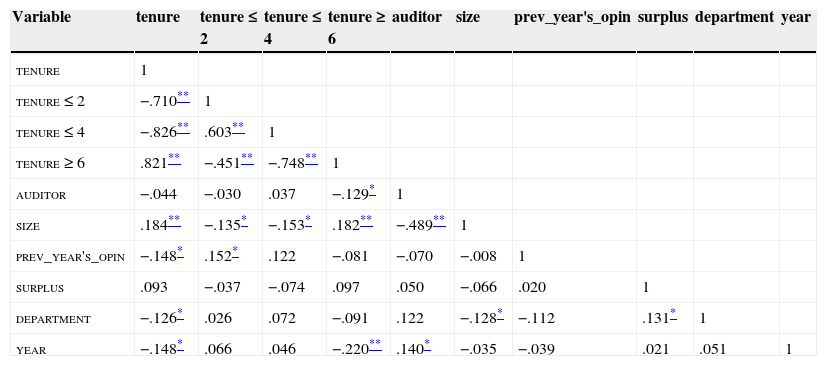

Lastly, Table 5 shows the correlation matrix between the different variables. Only one of the correlation exceeds 0.40 (variables size and auditor) suggesting that there are no multicollinearity problems in the data (Vermeer et al., 2009).

Correlation matrix.

| Variable | tenure | tenure≤2 | tenure≤4 | tenure≥6 | auditor | size | prev_year's_opin | surplus | department | year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tenure | 1 | |||||||||

| tenure≤2 | −.710** | 1 | ||||||||

| tenure≤4 | −.826** | .603** | 1 | |||||||

| tenure≥6 | .821** | −.451** | −.748** | 1 | ||||||

| auditor | −.044 | −.030 | .037 | −.129* | 1 | |||||

| size | .184** | −.135* | −.153* | .182** | −.489** | 1 | ||||

| prev_year's_opin | −.148* | .152* | .122 | −.081 | −.070 | −.008 | 1 | |||

| surplus | .093 | −.037 | −.074 | .097 | .050 | −.066 | .020 | 1 | ||

| department | −.126* | .026 | .072 | −.091 | .122 | −.128* | −.112 | .131* | 1 | |

| year | −.148* | .066 | .046 | −.220** | .140* | −.035 | −.039 | .021 | .051 | 1 |

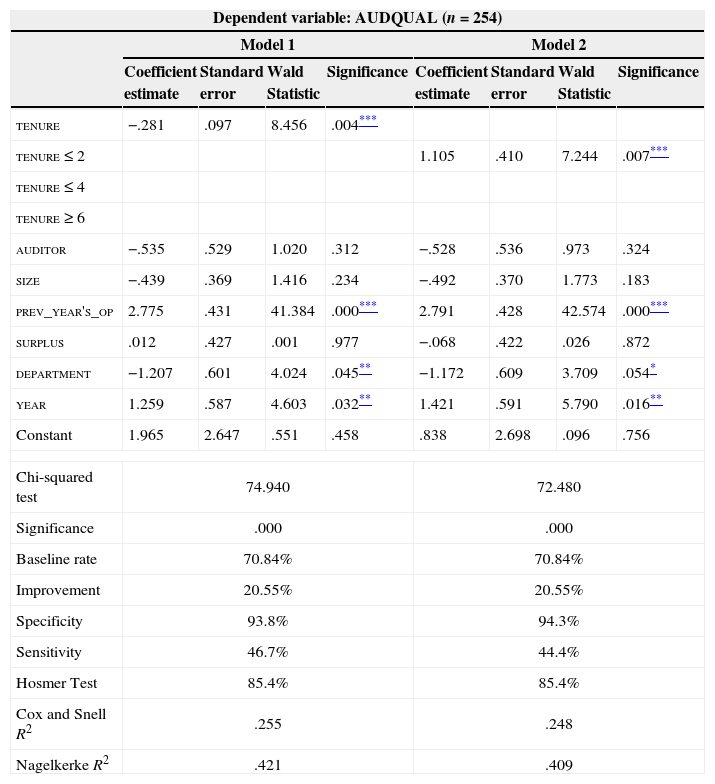

Table 6 shows the results of the four estimated logistic regression models for the period 2003–2010, which differ only in the ways the variable aud_tenure is defined. The results are consistent with those obtained in the univariate analysis, apart from the year variable, which is now statistically significant.

Logistic regression results.

| Dependent variable: AUDQUAL (n=254) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||

| Coefficient estimate | Standard error | Wald Statistic | Significance | Coefficient estimate | Standard error | Wald Statistic | Significance | |

| tenure | −.281 | .097 | 8.456 | .004*** | ||||

| tenure≤2 | 1.105 | .410 | 7.244 | .007*** | ||||

| tenure≤4 | ||||||||

| tenure≥6 | ||||||||

| auditor | −.535 | .529 | 1.020 | .312 | −.528 | .536 | .973 | .324 |

| size | −.439 | .369 | 1.416 | .234 | −.492 | .370 | 1.773 | .183 |

| prev_year's_op | 2.775 | .431 | 41.384 | .000*** | 2.791 | .428 | 42.574 | .000*** |

| surplus | .012 | .427 | .001 | .977 | −.068 | .422 | .026 | .872 |

| department | −1.207 | .601 | 4.024 | .045** | −1.172 | .609 | 3.709 | .054* |

| year | 1.259 | .587 | 4.603 | .032** | 1.421 | .591 | 5.790 | .016** |

| Constant | 1.965 | 2.647 | .551 | .458 | .838 | 2.698 | .096 | .756 |

| Chi-squared test | 74.940 | 72.480 | ||||||

| Significance | .000 | .000 | ||||||

| Baseline rate | 70.84% | 70.84% | ||||||

| Improvement | 20.55% | 20.55% | ||||||

| Specificity | 93.8% | 94.3% | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 46.7% | 44.4% | ||||||

| Hosmer Test | 85.4% | 85.4% | ||||||

| Cox and Snell R2 | .255 | .248 | ||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | .421 | .409 | ||||||

| Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient estimate | Standard error | Wald statistic | Significance | Coefficient estimate | Standard error | Wald statistic | Significance | |

| tenure | ||||||||

| tenure≤2 | ||||||||

| tenure≤4 | .768 | .426 | 3.249 | .071* | ||||

| tenure≥6 | −1.012 | .515 | 3.865 | .049** | ||||

| auditor | −.674 | .529 | 1.622 | .203 | −.705 | .525 | 1.801 | .180 |

| size | −.519 | .362 | 2.055 | .152 | −.516 | .362 | 2.031 | .154 |

| prev_year's_op | 2.789 | .420 | 44.089 | .000*** | 2.828 | .425 | 44.304 | .000*** |

| surplus | −.015 | .416 | .001 | .972 | −.003 | .418 | .000 | .995 |

| department | −1.137 | .595 | 3.658 | .056* | −1.099 | .588 | 3.499 | .061* |

| year | 1.487 | .584 | 6.490 | .011** | 1.250 | .600 | 4.350 | .037** |

| Constant | .991 | 2.661 | .139 | .709 | 1.714 | 2.611 | .431 | .512 |

| Chi-squared test | 68.560 | 69.424 | ||||||

| Significance | .000 | .000 | ||||||

| Baseline rate | 70.84% | 70.84% | ||||||

| Improvement | 21.68% | 22.25% | ||||||

| Specificity | 94.3% | 94.7% | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 48.9% | 48.9% | ||||||

| Hosmer Test | 86.2% | 86.6% | ||||||

| Cox and Snell R2 | .237 | .239 | ||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | .390 | .394 | ||||||

Notes: The model has a high explanatory power, with a highly significant chi-squared test. Another way to assess the performance of the maximum likelihood model is to measure the percentage of correct observations and compare it to the classification rate that would be obtained by chance [the baseline rate, which is equal to a2+(1−a)2, where a is the proportion of audit reports which have received a qualified opinion (17.72%) in the sample]. This model predicts the likelihood of getting a qualified opinion better than a random model would, with a classification improvement that ranges from 20.55 percent to 22.25 percent, which is close to the improvement of 25 percent suggested by Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black (1995).

The specificity (its capacity to correctly predict reports with an unqualified opinion) of the model is very good to excellent, while its sensitivity (its capacity to correctly predict reports with a qualified opinion) is good. At the same time, the global capacity to correctly classify the cases, measured using the Hosmer and Lemeshow Test, ranges from 85.4 percent to 86.6 percent. Pseudo R2 measures (Cox & Snell and Nagelkerke) confirm that the model has very good explanatory power.

The results provide evidence for the main variable of interest for this study. Auditor tenure is significant whether there is a linear relation (tenure) or not (tenure≤2; tenure≤4; tenure≥6) with the variable AUDQUAL. The results for model 1 suggest that the longer the auditor tenure is, the lesser the likelihood of receiving a qualified report, and so the lower the quality of the audit. Previously quoted studies (Deis & Giroux, 1992; Levinthal and Fichman, 1988; Vanstraelen, 2000) coincide when stating that long-term auditor–client relationships significantly increase the likelihood of auditors issuing an unqualified opinion.

Results obtained when dummy variables are used (models 2–4) to measure tenure indicate that this variable shows a positive sign and is statistically significant for auditor–foundation relationships of fewer than 5 years (models 2 and 3) and a negative, statistically significant sign for relationships over 5 years (model 4). In other words, when the auditor has been auditing a foundation for at least 6 years the likelihood of it getting a qualified report is reduced.

Overall, the empirical results for Spanish state-owned foundations show that while audit quality decreases as tenure increases, this quality loss does not become apparent until the sixth year of the auditor–client relationship as audit quality actually increases over the first five years.

As far as the control variables are concerned, it should be pointed out that the variable prev_year's_opin seems to play an important part; the sign is positive and statistically variable and suggests that foundations which have received a qualified report one year tend to receive the same the following year.

The variable department shows a negative, statistically significant sign, suggesting that belonging to the Tax and Finance Department reduces the likelihood of receiving a qualified report. This result is in accordance with that of Keating et al. (2005) as it shows that the sector a foundation belongs to, in this case its departmental relationship, can affect audit report opinion.

The variable year's sign is positive and statistically significant for 2003. This demonstrates the repercussions of the change in Foundation Law regulations which came into effect in 2003 and which substantially modified the previous regulations concerning auditor type and made auditing of large foundations compulsory. 2003 is when a large number of foundations were audited for the first time by the IGAE instead of by private firms.

Finally, the study highlights the fact that the variables auditor, size and surplus do not appear to influence audqual.

The robustness of the results was tested by using alternative definitions for some variables. Specifically, the variable tenure was substituted with the natural log of the number of consecutive years the foundation has been audited by the same auditor; surplus is defined as continuous and size is defined in three additional ways – total assets in euros, revenues in euros and the natural log of revenues. In each case the results do not change.

6Summary and conclusionsThe study examines the auditor tenure relationship with audit quality, the latter being considered from the point of view of external users.

Using a sample of 254 audits carried out on Spanish state-owned foundations between 2003 and 2010, the results reveal that such a connection does exist. In other words, it shows that a long relationship between a foundation and its auditor increases the likelihood of the auditor issuing a clean report. Auditor performance is, however, different in the first few years as the probability of a qualified report increases. In other words, audit quality, measured as the likelihood that an auditor will submit a qualified opinion, increases over the first five years of the relationship and then decreases.

Multivariate analysis results are consistent with univariate ones and may be regarded as generally robust to alternative specifications and sensitivity analysis.

The study contributes to the literature on the relationship between auditor tenure and audit quality in an environment where there is no mandatory auditor rotation and in a sector, non-profit making, where empirical research is very limited.

The results from this research also contribute to literature on factors which affect audit quality as they suggest that the opinion from the previous year's report, sector and year are all factors which play a major part in audit quality.

These findings also provide useful evidence to regulators, legislators, and financial statement users given that it suggests the need for the introduction of tenure-reducing measures which, at the same time, also ensure a minimum tenure period.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare not to have any conflict of interest.