The main problems that arise in adopting most enterprise resources planning (ERP) strategies come from organizational, rather than technical, issues, for example, social and cultural barriers, and user resistance. This paper analyzes the impact of cultural factors on user attitudes toward ERP use in public hospitals and identifying influencing factors. The theoretical grounding for this research is the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). The proposed model has six constructs (“resistance to be controlled”, “resistance to change”, “perceived risks”, “perceived usefulness”, “perceived ease of use”, and “attitude toward using”), and nine hypotheses have been generated from the connections between these six constructs. Results suggest important practical implications for attitude toward using ERP and to develop an understanding about how to improve this attitude in hospitals.

La mayor parte de los problemas que surgen en la implantación de sistemas ERP tienen su origen en causas de tipo organizativo más que en causas técnicas, como por ejemplo, las barreras sociales o culturales y la resistencia por parte de los usuarios. Este trabajo analiza el impacto de factores culturales sobre la actitud hacia el uso de sistemas ERP en un hospital público. El marco teórico empleado es el modelo de aceptación tecnológica (TAM). El modelo propuesto consta de seis constructos (“resistencia a ser controlado”, “resistencia al cambio”, “riesgo percibido”, “facilidad de uso percibida”, “rendimiento percibido”, y “actitud hacia el uso”) y nueve hipótesis, que han sido generadas a partir de las conexiones entre los constructos. Los resultados sugieren importantes implicaciones prácticas respecto a la actitud hacia el uso de sistemas ERP y cómo mejorar este actitud en los hospitales.

During the last decades health care managers tried to maximize hospitals’ efficiency, without reducing the quality of health care services provided to the patients (Calzado, García, Laffarga, & Larrán, 1998; Escobar, Escobar, & Monge, 2014; Herwartz & Strumann, 2014; Pizzini, 2006). This imperative has been reinforced in recent years as a consequence of the lack of available public resources for meeting the ever-increasing demand for health care services.

Hospital information systems are usually heterogeneous and autonomous (Koumbati, Temistocleous, & Irani, 2006). However, to improve the efficiency of the hospital sector, it has been proposed that integrated management systems should be applied in these health care organizations. These integrated systems would help to improve hospital’ processes and reduce operating costs (AECA, 2014; Alshawi, Themistocleous, & Almadani, 2004; Berchet & Habchi, 2005; Kansal, 2006; Van Merode, Groothuis, & Hasman, 2004).

The behavior of health care personnel in relation to the management of information is directly related to their status as primarily clinical rather than administrative personnel. The clinical personnel constitute a power group that, informally, exerts considerable influence in the management decisions taken within the hospital (Bloom, 1991; Soh & Sia, 2004). As a consequence of the power structure existing in hospitals, information is usually fragmented between clinical and non-clinical topics or areas, which can make the use of integrated management systems difficult or impossible.

The control of information is sometimes used to legitimize and maintain the structures of power existing in an organization (Escobar, Escobar, & Monge, 2010). To prevent this phenomenon, information systems can be employed to redistribute power among the different members of the organization (Abernethy & Vagnoni, 2004). The implementation of new information systems in a hospital represents a possible vehicle for the transformation of a “de facto” power structure into a different, more formal kind of power structure, by involving all the personnel, clinical and non-clinical, in the functions of management and supervision of the diverse activities of the hospital (Ribeiro & Scapens, 2006; Scapens & Jazayeri, 2003).

However, it must be recognized that the introduction of new information systems in a hospital has a direct impact on the behavior of the clinical personnel in relation to the acceptance of information technologies (Koumbati et al., 2006; Mc Ginnis, Pumphrey, Trimmer, & Wiggins, 2004; Pizzini, 2006). In this context, Soh and Sia (2004) emphasized the influence that power groups exert over the implementation of information systems. Thus, sometimes non-compatible software packages are implemented in specific hospital contexts (Escobar et al., 2010).

There are two main approaches for integrating information in hospitals: complete and partial (Stefanou & Revanoglou, 2006). The complete approach is based on a single integrated module program encompassing clinical, administration, and financial data using different applications, such as patient sign-in and discharge information, the locations of first aid kits, invoicing and pharmacy data, etc. Anderson (1997) considers that personnel reject these integration systems, as they are normally reluctant to change their work routines, and feel that closer supervision might be problematical. Organizational routines that reflect institutionalized practices are slow to change and such changes often face resistance (Granlund & Malmi, 2002). Soh and Sia (2004) argues that this approach to implementing ERPs is not valid for hospitals. Conversely, management consider this integration approach to be efficient, and that its cost is offset by its benefits (Stefanou, 2001). Partial integration involves using the ERP's administrative and financial modules and connecting them via a series of specific applications (radiology, laboratory, etc.).

The current trend in the health care sector is to implement management strategies focused on improving efficiency in hospitals. It has been argued that ERP is the most suitable type of information system for supporting the management of organizations like hospitals (Escobar et al., 2010; Van Merode et al., 2004). Initially, processes of “partial integration” are being carried out, using the administrative and financial modules of ERP, and keeping specific applications for other areas. As a general rule, ERPs have been employed to facilitate integration among all functional areas within a company organization (Alshawi et al., 2004; Davenport, 1998; Kansal, 2006; Klaus, Rosemann, & Gable, 2000; Muscatello, Small, & Chen, 2003). In the case of hospitals, they are being used to achieve, as a minimum, the integration of planning within the financial area. ERPs have been developed in response to the need to manage across global businesses, a difficult task made more so in organizations such as hospitals, where each unit business is using different systems and technologies (Imra, Murphy, & Simon, 2000).

It is not easy to deal with this integration process in hospitals because of their organizational issues. The major problems arise in most ERP adoptions because of organizational rather than technical issues, for example social and cultural barriers, and user resistance (Pan, Newell, Huang, & Galliers, 2007). In hospitals, ERP systems are welcomed as long as they provided direct benefit to their work and eased their work practices (Escobar et al., 2010; Nicolaou, 2004). At the same time, hostile reactions toward the ERP system were evident since it implied control mechanisms of their work and introduced new work tasks previously performed by others (Jensen & Aanestad, 2007). These hostile reactions could be strong in Spanish public hospitals. In Spanish public hospitals, health care personnel are public servants with permanent contracts, so it is very important to analyze their attitude toward using new technologies because they are in a very strong position to hinder new systems and process re-engineering.

The aim of previous research was focused on exploring critical factors related to success and failure of the ERP implementation process (Berchet & Habchi, 2005; Bingi, Sharma, & Godla, 1999; Finney & Corbett, 2007; Muscatello et al., 2003; Nah, Lau, & Kuang, 2001; Santamaría-Sánchez, Núñez-Nickel, & Gago-Rodríguez, 2010). However, a deeper knowledge of factors related with attitude toward using ERP systems in hospitals is required. The main objective of this paper is to analyze the impact of cultural factors on the attitude toward using ERP systems in public hospitals identifying influencing factors. Cultural factors that have been included in this paper refer to organizational culture. Organizational culture can be defined as the general pattern of mindsets, beliefs and values that members of the organization share in common, and which shape the behaviors, practices and other artifacts of the organization which are easily observable (Prajogo & McDermott, 2005; Sathe, 1985; Schein, 1985). Understanding these factors provides the opportunity to explore which actions might be carried out to boost adoption by potential users.

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989, 1993) is generally used to analyze individuals’ acceptance of new technologies (Cornell, Eining, & Hu, 2011; Dasgupta, Granger, & McGarry, 2002) and has become established as a robust, powerful and parsimonious model for predicting attitude toward usage (Hu, Chau, Sheng, & Tam, 1999; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). Apart from the aforementioned aims, our analysis will validate TAM in the context of Spanish public hospitals while also identifying new external variables which affect the constructs of “perceived usefulness”, “perceived ease of use”, and “attitude toward using”.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows: in the next section, we provide a theoretical background and posit the hypotheses; we then describe our research methodology and present data analysis and results; and we then conclude, discussing implications for future research.

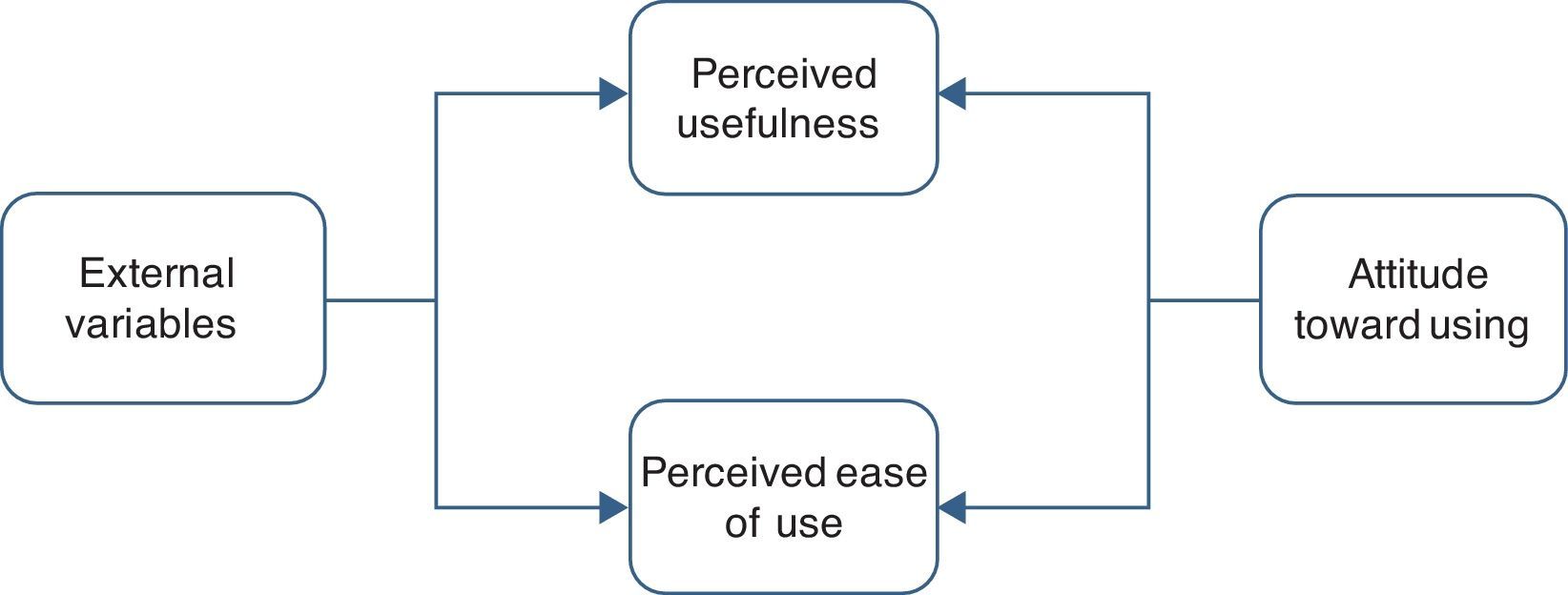

2Background2.1Technology Acceptance ModelTAM specifies the causal relationships between systems design features, “perceived usefulness”, “perceived ease of use” and “attitude toward using” (Davis, 1993). The basic premise of this model is that the more accepting users are of new systems, the more they are willing to make changes in their practices and use their time and effort to actually start using the system (Jones, McCarthy, & Halawi, 2010).

TAM proposes two important determinants to analyze what causes people to accept or reject information technology (IT): “perceived usefulness” and “perceived ease of use”. “Perceived usefulness” is defined as the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance. On the other hand, “perceived ease of use” refers to the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free of effort (Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989) (Fig. 1).

TAM addresses the issue of how users accept and use a technology (Teo & Noyes, 2011). Several papers have demonstrated the usefulness of TAM for analyzing user behavior as well as intention of use of a wide range of IT (Chau & Hu, 2002; Chin and Gopal, 1995; Gefen & Straub, 1997; Hu et al., 1999; Igbaria, Parasuramen, & Baroudi, 1996).

Significant progress has been made over the last decades in explaining and predicting user acceptance of IT. In particular, substantial theoretical and empirical support has accumulated in favor of the TAM and this model compares favorably with alternative models such as the Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behavior (Venkatesh, 1999; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000).

During the last two decades TAM has been used to predict user acceptance of a technology. This model has been used to explain intention of use by different types of users, including an analysis of the conditions in which technology is used (Schniederjans & Yadav, 2013; Venkatesh, 2000), gender aspects (Gefen & Straub, 1997; Venkatesh & Morris, 2000), and cultural factors (Teo, Lee, & Chai, 2008).

A number of studies have been carried out in the context of ERP using TAM, often with significant results. Ramayah and Lo (2007) examined the impact of shared beliefs concerning the benefits of ERP. Their findings support that “perceived ease of use” mediates partially the effects of shared beliefs concerning the usefulness of the ERP. Amoako-Gyampah and Salam (2004) found that both training and project communication influence the shared beliefs that users form about the benefits of ERPs and that the shared beliefs influence the “perceived usefulness” and “perceived ease of use” of this technology.

Bueno and Salmerón (2008) analyzed the influence of top management support, communication, cooperation, training and technological complexity in ERPs acceptance. Other factors related with user predisposition to new technology have been considered. For instance, Shivers and Charles (2006) found that readiness for change is a significant predictor of attitude toward usage of the ERP.

Lee, Lee, Olson, & Chung (2010) examined the impact of organizational support on behavioral intention regarding ERP implementation based on TAM. They found that this is an important factor for “perceived usefulness” and “perceived ease of use”. Recently, Sternad, Gradisar, & Bobek (2011) examined a wide range of external factors that could influence the intention to use an ERP. The factors technological innovativeness, computer anxiety, computer self-efficacy, computer experience, data quality, system performance, user manual helpfulness, ERP functionality business processes fit, social influence, ERP support, ERP communication and ERP training were included in this study using TAM, finding some influences on the attitude toward using ERP.

These critical success factors are helpful and appropriate in explaining both the initial failure and the eventual success of the implementation (Akkermans & van Helden, 2002). However, making an ERP system work is more than an issue of technical expertise or social accommodation: it is an ongoing, dynamic interaction between the ERP system, different groups in an organization and external groups, such as vendors, management consultants and shareholders (Newman & Westrup, 2005). Therefore, additional evidence is required about the influence of cultural factors on the attitude toward usage.

In general, the literature on ERPs focuses on implementation and other technical issues such as efficiency, effectiveness, and business performance; there is a relative lack of attention given to the social context, that is, user acceptance (Grabski, Leech, & Schmidt, 2011). Furthermore, it has been tested primarily on technologies that are relatively simple and voluntary (e.g. e-mail, word processors). Several researchers have recommended that TAM be revised to address user attitude, intent and behavior when applied to complex IT in organizational settings where usage is generally considered mandatory (Nah, Tan, & Teh, 2004). Because ERP users impact others, they do not have the choice to avoid the system, regardless of their attitudes about ERP systems (Sternad et al., 2011). Therefore, following Nah et al. (2004), we analyze users’ attitudes toward ERP, which refers to users’ voluntary mental acceptance of the system. Therefore, TAM can be considered valuable and useful for explaining or predicting attitude toward using ERP systems in public hospitals.

ERP systems might be implemented successfully from a technical perspective, but success depends on ERP users’ attitudes toward the system (Kwahk & Lee, 2008). Several studies suggest that ERP failure is related to user attitudes toward ERP systems (Umble, Haft, & Umble, 2003). Moreover, most of these studies consider a limited number of factors which influence the attitude toward usage and acceptance of ERPs (Sternad et al., 2011). Nevertheless, previous literature yields little in the way of users's attitude in hospitals that contributes to a wider understanding of ERP acceptance in this context.

Apart from the inherent complexity of the service they provide, hospitals are an example of organizations with differing cultural functional areas; there are different groups able to exert pressure during the set-up of an ERP system. Should the organizational culture influence the attitude toward using ERP systems (Palanisamy, 2008), it is worth carrying out by going deeper into the study of organizations with different coexisting cultures, while paying special attention to how and which variables influence the attitude toward using ERP systems (Cavalluzzo & Ittner, 2004). In spite of the documented empirical applicability of TAM, additional efforts are needed to validate existing research results, particularly those involving different technologies, users, and/or organizational contexts, in order to extend the model's theoretical validity and empirical applicability.

The aim of this paper is to extend the number of observed factors which influence attitude toward usage in public hospitals. We try to understand the relationships between hospitals’ organizational culture and users’ attitude. Apart from the abovementioned aims, this analysis will validate the TAM in the context of ERP in public hospitals while also identifying new external variables which affect the constructs of “perceived usefulness” and “perceived ease of use”.

2.2HypothesesThe first three hypotheses in the proposed model are based on three basic relationships set up in TAM (Davis, 1989; Davis et al., 1989). TAM arises from the theory that a technology viewed by people to be easier to use and/or to have higher usefulness is more likely to be accepted. Therefore, TAM establishes that “perceived ease of use” and “perceived usefulness” affect the “attitude toward using”. Moreover, TAM assumes that “perceived ease of use” of a technology has an effect on the “perceived usefulness”. Several studies have confirmed this relationship (Liaw & Huang, 2003; Shang, Chen, & Shen, 2005), others have rejected it (Agarwall & Prasad, 1999; Venkatesh & Morris, 2000), while others do not take it into account (Gefen & Straub, 1997; Liu & Wei, 2003). The intensity or direction of this relationship is not always the same, depending on the degree of innovation of the technology (Peffers & Dos Santos, 1996). Therefore, the first set of hypotheses for this study is stated as follows:H1 “Perceived ease of use” has a significant effect on the “perceived usefulness” of ERP in public hospitals. “Perceived ease of use” has a significant effect on the “attitude toward using” ERP in public hospitals. “Perceived usefulness” has a significant effect on the “attitude toward using” ERP in public hospitals.

“Perceived ease of use” and “perceived usefulness” have traditionally been used as determinants of individual technology adoption (Koufaris, 2002; Szajna, 1994). However, these two variables do not fully reflect users’ motivation to adopt an ERP in public hospitals. To complete the proposed model, we include three external variables related to cultural factors which might be relevant for health care personnel to adopt ERP. These external variables might influence the attitude toward a behavior indirectly by influencing the salient beliefs about the consequences of exhibiting the behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

2.2.1Resistance to change (RC)The alignment of the standard ERP processes with the company's business processes is for a long time considered as a critical step of the implementation process (Botta-Genoulaz, Millet, & Grabot, 2005). That is because process reengineering is frequently linked with ERP implementations (Wenrich & Ahmad, 2009).

ERP implementations almost always require business process reengineering, because of the need to adapt the organizational processes to match the capabilities of the software (Amoako-Gyampah & Salam, 2004). There are several reasons that cause individuals in a hospital to have a low readiness for change: the purpose is not made clear, participants are not involved in planning, the habit patterns of the individuals are ignored, excessive work pressure is involved, and/or the current condition seems satisfactory (Battilana & Casciaro, 2013; Carlstrom & Ekman, 2012; Schiavone, 2012).

Venugopal and Suryaprakasa (2011) suggest that the existing structures embodied in the well-entrenched legacy system will offer greater resistance to the work flows dictated by the ERP system. Therefore, this process reengineering could cause some resistances to change by potential users and affect the attitude toward using ERP in hospitals. Sometimes, health care personnel are unwilling upgrade to a new technology because ERPs are not flexible enough to adapt to the processes of the hospital. We can state these two hypotheses:H4 “Resistance to change” has a significant effect on “perceived usefulness” of ERP in public hospitals. “Resistance to change” has a significant effect on “perceived ease of use” of ERP in public hospitals.

A health care system failure can have serious consequences. The perception of possible risks related to ERP could affect users’ attitude. Health care personnel make continuous efforts to reduce risks due to the serious repercussions involved. Legal and economic factors, as well as public trust in the health care system, have also been affected by these risks. Therefore, perceived risk could have a significant impact on the attitude toward using new technologies (Cho, 2004).

Many patients’ processes in hospitals differ substantially in their degree of variability and stochasticity. As a result the logistic processes supporting the patients’ processes may differ to the same degree (Van Merode et al., 2004).

ERP have significant advantages. All information is centralized in a single relational database accessible by all modules, eliminating the need for multiple entries of the same data (Muscatello et al., 2003). However, ERP requires that processes be described very precisely. Often the formal information is not complete, and the implementers do not know where the different types of process knowledge reside in the organization (Van Stijn & Wensley, 2001). Therefore, health care personnel could think that implementing ERP would be risky because it would either lead to missing functions or to suboptimizing parts of the organization. The next hypotheses can be stated:H6 “Perceived risks” have a significant effect on “perceived usefulness” of ERP in public hospitals. “Perceived risks” have a significant effect on “perceived ease of use” of ERP in public hospitals.

By centralizing operational information in one place where it can be shared by all the company's key functional systems and standardizing business processes across functions, an ERP indeed offers the promise of integration (Davenport, Harris, & Cantrell, 2004). Integration and standardization of data and processes that usually accompanies it allow improving organizational control systems. Therefore, ERP configurations can dramatically affect controls and how actions are made visible (Quattrone & Hopper, 2005).

ERPs involve the centralization of control over information. This is a quality consistent with hierarchical, command and control organizations with uniform cultures (Davenport, 1998). However, public hospitals have not got these characteristics. Therefore, hostile reactions toward the ERP system should be evident since it implied new control mechanisms (Jensen & Aanestad, 2007). Consequently, the final group of hypotheses is:H8 “Resistance to be controlled” has a significant effect on “perceived usefulness” of ERP in public hospitals. “Resistance to be controlled” has a significant effect on the “attitude toward using” ERP in public hospitals.

The proposed model has six constructs and nine hypotheses have been generated from the relations of these six constructs (Fig. 2).

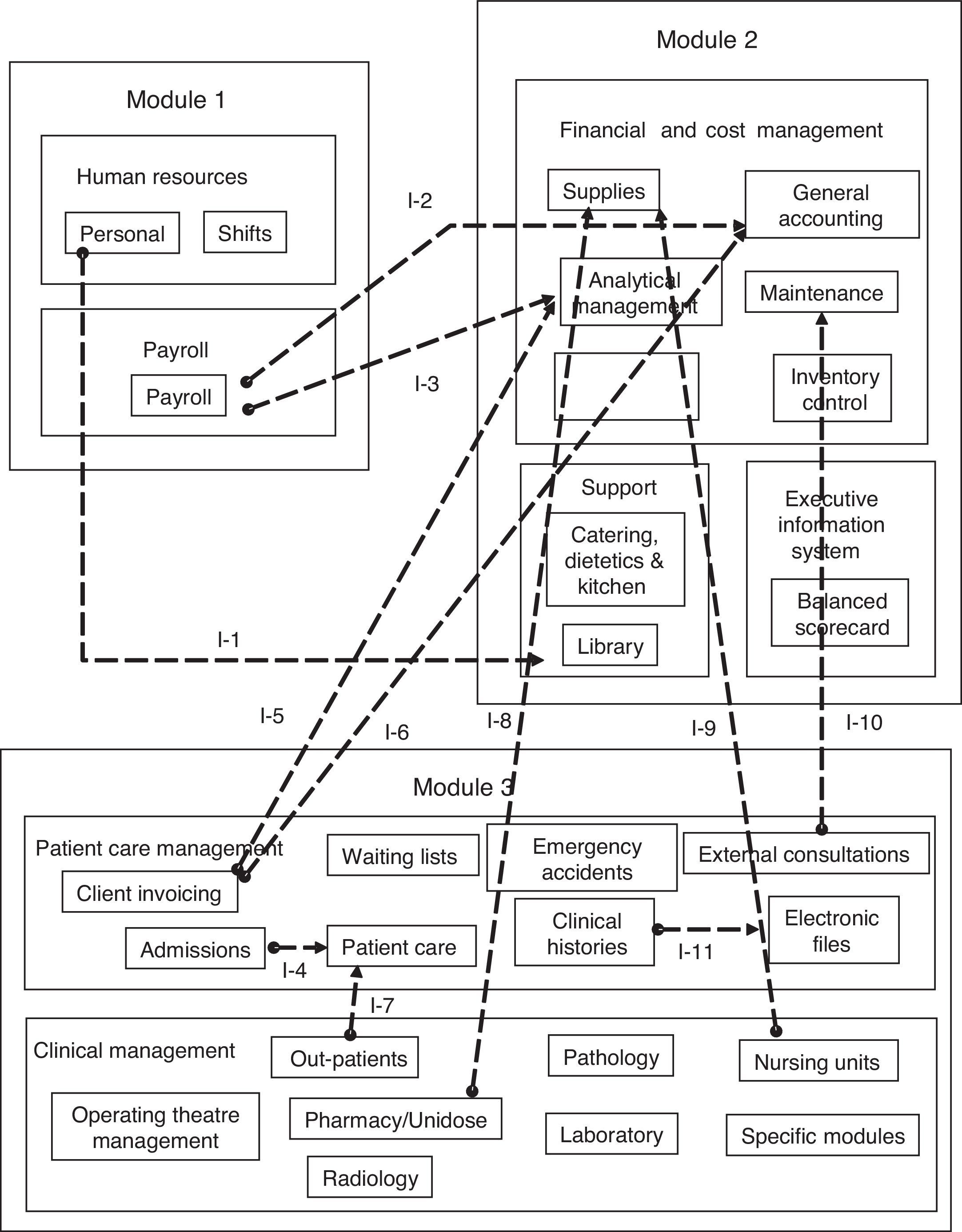

3MethodologyA field survey was employed to test our research model. The study was carried out in a medium Spanish public hospital (Alcorcón Hospital) located in Madrid. Its Hospital Information Systems (HIS) is a set of procedures and functions directed toward the collection, production, assessment, storage, recovery, and distribution of items of information within the organization, oriented to promoting the flow of these items from the points where they are generated to the final intended recipients. It was implemented at the beginning of the last decade and comprises of 3 modules and 11 applications (Fig. 3).

As we can see, the HIS is not a single integrated module program encompassing clinical, administration, and financial data. Instead, three different modules were implemented connected by 11 interfaces. Therefore, the HIS consists of three “big systems”, one system for each module.

The functions included in each module and the eleven interfaces are the following:

- -

Module 1: Human Resources (Personnel Management and Management of Shifts) and Payroll.

- -

Module 2: Financial and Cost Management (Supplies, General Accounting, Analytical Management and Management of Costs, Payment of Suppliers’ Invoices, Inventory Management and Maintenance), Supporting Services (Catering, Dietetics and Kitchen) and Executive Information System.

- -

Module 3: Patient Care Management (Admission of in-patients, Waiting lists, Emergencies and Emergency Boxes, External Consultations, Electronic Clinical History, Invoicing to the Customer) and Clinical Management (Management of Operating Theaters, Radiology, Out-patients, Ward Control Points, Control Infrastructure, Generation of Medical Reports, Pharmacy, Pathology and Nursing Units, Document Manager, Medical Protocols, Laboratory).

- -

Applications: Laboratory, Dietetics, Doctor, Gacela, Carevue, GPC, Invoicing, Library, Balanced Scorecard, Pharmacy and Pathology.

In the standard version of each module there is a set of interfaces for the exchange of information between them. However, this is not the case with the different applications acquired; for this reason it was necessary to incorporate up to 11 interfaces, which are described below:

- -

Interface I-1: It connects the Personnel and the Library Management Modules. Its objective is to load onto the database of the Library the data of the hospital personnel that are considered necessary for managing borrowings of publications.

- -

Interface I-2: It exchanges data between the Payroll Module and the Financial Accounting Module, with the object of recording the accounting details necessary for each Payroll payment.

- -

Interface I-3: This is similar to the previously described interface; its purpose is to exchange data between the Payroll Module and the Analytical Accounting Module, assigning the costs of each payroll item to its corresponding cost center.

- -

Interfaces I-4 and I-7: The Patient Care Module is generated in function of the data obtained when the patient is admitted to hospital. Therefore, it is necessary to transfer information corresponding to each patient.

- -

Interface I-5: From the data of the invoices, which reflect the cost of all the services and products that each patient has consumed during their hospitalization, the total costs of each hospitalization are determined and these costs are assigned to the corresponding units.

- -

Interface I-6: In the same way as in the previous interface, the costs of each period of hospitalization are assigned the corresponding units; the interface of Invoicing with Financial Accounting allows the invoicing to be assigned to the account of each unit.

- -

Interfaces I-8 and I-9: Among their functions, the Nursing and Pharmacy Modules support the control of the ward sub-stores and orders for supplies placed on the central warehouse; therefore interfaces are created that enable both the completion of orders placed automatically in function of the level of stock of certain materials, and the generation and shipment of orders placed manually to the Supplies Module.

- -

Interface I-10: It allows making modifications to the planned capacity of the External Consultations, in function of the periods of time that the equipment of each Service is not available due to maintenance or repair work.

- -

Interface I-11: This interface allows the localization of the electronic file of documents associated with each medical history from the application that manages the Clinical Records.

Partial integration involves using the ERP's administrative and financial modules (Module 2), connecting them via a series of specific applications (radiology, laboratory, etc.). ERP software that had been chosen for the Module 2 by the hospital was SAP R/3. SAP R/3 was seen as an immensely powerful but notoriously complex system. The selection of SAP R/3 as Module 2 was well documented and its implementation has generally been portrayed as successful. In this paper, we seek to explore the acceptance of SAP R/3 in public hospitals and to determine in more depth the impact of cultural factors on its acceptance by health care personnel.

The study took place among all SAP R/3 users in this public hospital. Data were collected in September 2011. Almost all ERP users participated in this research. The response rate was over 80%, with a total of 59 valid replies collected. The questionnaire has several items related to each of the constructs included in the model. The survey items were measured using a seven-point Likert scale. All items ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Theoretical constructs were operationalized using validated items from prior research. “Perceived ease of use”, “perceived usefulness” and “attitude toward using” SAP R/3 were measured using items adapted from Davis (1989, 1993), Davis et al. (1989) and Mathieson (1991). The measurement of “resistance to change” was adapted from Dasgupta, Agarwal, Ioannidis, & Gopalakrishnan (1999) and Moore and Benbasat (1991). “Perceived risks” items’ measures drew their inspiration from Carr, Zhang, Klopping, & Min (2010). Items for “resistance to be controlled” were developed for this research.

This research is based on a regression analysis of latent variables using the optimization technique of the Partial Least Squares (PLS) to develop a model that represents the relationships among the six proposed constructs measured by many items. The PLS is a multivariate technique to test structural models (Wold, 1985). The PLS method estimates the model parameters which minimize the residual variance of the whole model dependent variables (Hsu, Chen, & Hsieh, 2006); it does not require any parametric conditions (Chin, 1998) and is recommended for small samples with non-normal data (Hulland, 1999).

These PLS characteristics are different from those of the Structural Equations Models based on covariance analysis, which requires a high sample due to the sensitiveness of the chi-square test. Basically, the objective of the PLS modeling is predicting dependent variables, latent and manifest, maximizing the explained variance of the dependent variables and minimizing the residual variance of endogen variables (Lévy, Valenciano, & Michal, 2009). PLS method is more oriented to the model predictability (Chin & Frye, 2003) and the estimates’ stability will be measured by the Student's t statistic, issued from a bootstrapping made over random samples.

4Data analysis and resultsData analysis takes place via a two-stage methodology, in which the measurement model first is developed and evaluated separately from the full structural equation model (Gerbing & Anderson, 1988). The first step involves establishing individual reliability for each item, followed by determining the convergent and discriminate validity of the constructs.

Individual item reliability is determined via loadings or correlations between the item and the construct. The convergent validity of each construct is acceptable for a loading higher than 0.505 (Falk & Miller, 1992). Table 1 indicates the loading for each item. All variables comply with established conditions.

Items descriptive and loading.

| Construct | Indicator | Mean | Standard deviation | Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance to be controlled (RBC) | RBC1. ERPs enable managers improve quality of control activities. | 3.271186 | 1.627676 | 0.8329 |

| RBC2. Implementation of an ERP reduces the time related to control the individual behavior. | 2.745763 | 1.677367 | 0.9154 | |

| RBC3. ERPs with their databases and data analysis capacities can facilitate management control. | 2.694915 | 1.793227 | 0.9508 | |

| Resistance to change (RC) | RC1. Using ERPs is not compatible with aspects of my work. | 4.406780 | 2.035196 | 0.9329 |

| RC2. I think that using ERPs do not fit well with the way I like to work. | 3.949153 | 1.601979 | 0.9192 | |

| RC3. Using ERPs do not fit into my work style. | 3.813559 | 1.644998 | 0.9316 | |

| Perceived risks (PR) | PR1. There is a significant potential for loss data with ERPs. | 3.457627 | 2.119873 | 0.9412 |

| PR2. There is a significant risk of potential failure to using ERPs. | 3.254237 | 1.996490 | 0.9480 | |

| PR3. Using ERPs is not completely sure. | 4.016949 | 1.645176 | 0.8958 | |

| Perceived usefulness (PU) | PUE1. Using ERPs improve my job performance. | 4.576271 | 1.599605 | 0.9123 |

| PUE2. ERPs support critical aspect of my job. | 4.677966 | 1.580492 | 0.9283 | |

| PUE3. Using ERPs allows me to accomplish more work than would otherwise be possible. | 4.762712 | 1.664425 | 0.9364 | |

| Perceived ease of use (PEU) | PEU1. I do not become confused when I use ERPs. | 4.423729 | 2.094355 | 0.9278 |

| PEU2. I do not make errors when using ERPs. | 4.745763 | 2.186110 | 0.9394 | |

| PEU3. Interacting with ERPs is easy. | 4.711864 | 2.093099 | 0.9516 | |

| Attitude toward using (A) | A1. Using ERPs is a good idea | 5.491525 | 1.633411 | 0.9034 |

| A2. Using ERPs is pleasant | 5.220339 | 1.640729 | 0.8814 | |

| A3. Using ERPs is beneficial | 5.237288 | 1.557396 | 0.9057 | |

Reliability makes it possible to measure internal coherence of all the indicators in relationship to constructs. To verify the reliability of each indicator, the Cronbach coefficient alpha (Cronbach, 1970) and the composite reliabilities coefficient (Werts, Linn, & Jöreskog, 1974) were utilized, each ranging from 0 (no homogeneity) to 1 (maximum homogeneity). Both parameters are taken into account, as the first considers the contribution made by each indicator to the construct, while the second takes the respective item's loading into account. Table 2 indicates the values of each coefficient. Composite reliabilities are over the minimum acceptable limit of 0.70 (Gefen, Straub, & Boudreau, 2000; Nunnally, 1978). The Cronbach coefficient alpha levels are also shown in Table 2. They were all above 0.70, which is recommended for confirmatory research (Churchill, 1979).

Composite reliability, AVE and Cronbach coefficient alpha.

| Construct | Composite reliability | AVE | Cronbach alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance to be controlled (RBC) | 0.928071 | 0.811838 | 0.884200 |

| Resistance to change (RC) | 0.948958 | 0.861062 | 0.913416 |

| Perceived risks (PR) | 0.949444 | 0.862334 | 0.916416 |

| Perceived usefulness (PU) | 0.947275 | 0.856928 | 0.916488 |

| Perceived ease of use (PEU) | 0.957671 | 0.882934 | 0.933439 |

| Attitude toward using (A) | 0.925039 | 0.804459 | 0.877930 |

Discriminant validity was assessed by examining whether each item loaded higher on the construct it measured than on any other construct. The factor structure matrix of loadings and cross-loadings (Table 3) indicates that the measurement exhibited reasonable discriminant validity. Items measuring the same construct indicate distinctly higher factor loadings on a single construct than on other constructs. This is also an indication of the convergent validity of the measurement.

Factor structure matrix of loadings and cross-loadings (highest values in bold).

| Scale items | RBC | RC | PR | PU | PEU | A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC 1 | 0.8330 | 0.4926 | 0.3278 | −0.4079 | −0.4846 | −0.5646 |

| RBC 2 | 0.9154 | 0.1715 | 0.4038 | −0.3695 | −0.5738 | −0.6582 |

| RBC 3 | 0.9508 | 0.2964 | 0.5166 | −0.4986 | −0.6939 | −0.7882 |

| RC 1 | 0.2766 | 0.9329 | 0.3053 | −0.3681 | −0.4286 | −0.1807 |

| RC 2 | 0.3644 | 0.9192 | 0.3905 | −0.4042 | −0.4220 | −0.3720 |

| RC 3 | 0.3235 | 0.9316 | 0.2848 | −0.4017 | −0.3969 | −0.3122 |

| PR 1 | 0.5099 | 0.2364 | 0.9412 | −0.3874 | −0.7087 | −0.4789 |

| PR 2 | 0.4408 | 0.3012 | 0.9480 | −0.4084 | −0.6330 | −0.4190 |

| PR 3 | 0.3479 | 0.4663 | 0.8958 | −0.4007 | −0.5569 | −0.2653 |

| PU1 | −0.4084 | −0.4160 | −0.3875 | 0.9123 | 0.5811 | 0.5202 |

| PU2 | −0.4801 | −0.3547 | −0.5016 | 0.9283 | 0.6652 | 0.5897 |

| PU3 | −0.4311 | −0.4045 | −0.2961 | 0.9364 | 0.5515 | 0.6072 |

| PEU1 | −0.5947 | −0.4323 | −0.6670 | 0.6360 | 0.9278 | 0.5448 |

| PEU2 | −0.6255 | −0.3983 | −0.6668 | 0.5571 | 0.9394 | 0.5907 |

| PEU3 | −0.6326 | −0.4326 | −0.5963 | 0.6346 | 0.9516 | 0.5514 |

| A1 | −0.6961 | −0.2324 | −0.4405 | 0.5708 | 0.5069 | 0.9034 |

| A2 | −0.7101 | −0.3520 | −0.3474 | 0.5853 | 0.6007 | 0.8814 |

| A3 | −0.6106 | −0.2488 | −0.3474 | 0.5028 | 0.4953 | 0.9057 |

After individual item reliability and convergent and discriminate construct validity have been established, the structural model is examined. To test H1 through H9, a PLS analysis was performed. Regression coefficients are based on bootstrapping samples and not on samples estimator. It permits the generalization of the results and the computation of the t-value for each hypothesis (Lévy et al., 2009). The results are presented in Fig. 4, and Table 4 summarizes the relationships between the different constructs. The predictive capability of the model is satisfactory because all R-Squares are higher than 0.10 (Falk & Miller, 1992).

Summary of test results for the structural model.

| Hypothesis | Path | Standardized path coefficient | t-value | Supported? | Construct | R-squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PEU→PU | 0.559 | 3.048 | Yes, p<0.001 | Perceived usefulness | 0.447 |

| H4 | RC→PU | −0.162 | −1.995 | Yes, p<0.05 | ||

| H6 | PR→PU | 0.047 | 0.748 | No | ||

| H8 | RBC→PU | −0.075 | −0.496 | No | ||

| H5 | RC→PEU | −0.236 | −2.077 | Yes, p<0.05 | Perceived easy of use | 0.518 |

| H7 | PR→PEU | −0.602 | −5.450 | Yes, p<0.001 | ||

| H2 | PEU→A | −0.023 | −0.172 | No | Attitude toward using | 0.655 |

| H3 | PU→A | 0.347 | 2.179 | Yes, p<0.05 | ||

| H9 | RBC→A | −0.603 | −4.343 | Yes, p<0.001 | ||

TAM theory suggests that there is a significant positive relationship between “perceived ease of use”, “perceived usefulness” and “attitude toward using” ERPs in public hospitals (H1, H2, H3). These paths have been supported in the research model except for the path between “perceived ease of use” and “attitude toward using” (H2). Therefore, it should be noted that “perceived ease of use” does not necessarily lead to “attitude toward using”.

These results are according to other studies that have not found support for this hypothesis. For instance, Szajna (1996) posits that “perceived usefulness” has a direct influence on intention to use, whereas the “perceived ease of use” has only an indirect effect on intention to use through “perceived usefulness”.

This is also congruent with the findings of Chen, Zeng, Atabakhsh, Wyzga, & Schroeder (2003), who found that “perceived usefulness” appears to be the only construct that has a significant direct influence on intention. In general, the findings support the notion that when a technology is perceived by users to be easy to use or learn, such users will also project the system as being useful (Ignatius & Ramayah, 2005).

The findings indicate that “resistance to change” is negatively related to “perceived usefulness” and “perceived ease of use” of ERP in public hospitals, giving support for H4 and H5. The higher the “resistance to change”, the lower the “perceived usefulness” and “perceived ease of use”. Therefore, despite the potential benefits of ERPs “resistance to change” must be taken into account in order to achieve the desired results.

Insufficient attention has been paid to the problem of fundamental differences between the structures embedded in the organization (as reflected by its procedures, rules and norms) and those embedded in the package. Ideally, organizations should be able to assess, prior to implementation, the extent of the misalignment, so that they may better manage the process of bringing the organization and package into alignment (Soh & Sia, 2004).

This is a common challenge faced during ITs implementation (Jones, 2003; Lippert & Davis, 2006). The use of new technologies normally implies changes in the way tasks are carried out, sometimes generating reticence in those involved. Health care personnel are faced with acquiring new skills on a steep learning curve (Thuemmler, Buchanan, Fekri, & Lawson, 2009), which is not always in line with the way they usually work. This can be frustrating for health care managers; after they have invested in new technologies, they may find these technologies rejected by reticent heath care personnel.

The test results clearly suggest that “perceived risk” has a significant relationship with “perceived ease of use” (H7). Users who perceive high risks for losing data or system failures do not find them easy to use. Contrary to other cases (Carr et al., 2010), the relationship between “perceived risks” and “perceived usefulness” (H6) is not supported by the test results summarized in Table 4. Sometimes, “perceived risks” could imply that users do not perceive the usefulness of technology if there is a significant risk of potential failure. However, this relationship is not significant in this research.

One of the contributions of this research is to incorporate the construct “resistance to be controlled” to explain the attitude toward using ERPs in public hospitals. While H8 is not supported, the results show that health care personnel who find that ERPs enable managers improve quality of control activities and facilitate management control are more reluctant to use them (H9). This is a very important finding to explain “attitude toward using” IT in public hospitals by health care personnel due to its social and cultural barriers.

6Concluding remarksHospitals are undergoing significant changes, mainly due to ITs within the health care process. Within this framework, the use of ERPs has significant advantages. All information is centralized in a single relational database accessible by all modules, eliminating the need for multiple entries of the same data. Therefore, ERPs could help to improve quality of service while increasing efficiency.

This research integrates the appropriate information systems literature in order to enhance the knowledge of attitude toward using ERP from the health care personnel's perspective. A further theoretical contribution is the development and validation of survey measures for the constructs examined in this study, particularly for the constructs “resistance to be controlled”, “resistance to change”, and “perceived risks”. In a situation where theory is advanced, it is essential to involve the creation and validation of new measures, and such efforts are considered an important contribution to scientific practice in the information systems field (Straub, Boudreau, & Gefen, 2004). These measures can be utilized to examine other emerging technologies within the health care context.

In addition to the theoretical contribution, the research model suggests important practical implications for “attitude toward using” ERP and develops an understanding about how to improve this attitude in hospitals. Reducing the “resistance to be controlled”, the “resistance to change” and the “perceived risks” of using this technology by health care personnel is a central issue to get a better “attitude toward using” ERPs in public hospitals.

The success in the implementation of an ERP system could depend on the interaction of these three factors and its impact on users’ “attitude toward using”. These three factors should be managed during the implementation process to influence the attitude of users toward the use of ERP systems in the right way and, therefore, to increase the success probabilities.

Results support that health care personnel's “resistance to change” may be a serious cause for concern in implementing ERPs in public hospitals because it affects the “perceived ease of use” and “perceived usefulness” of this IT. To reduce personnel's “resistance to change”, managers must be prepared to talk candidly about the needs

for change, otherwise fear and uncertainty will remain a prevailing element that can damage morale and prevent successful implementation of the ERP at all levels of the organization (Bateh, Castaneda, & Farah, 2013). These significant relationships are also notable for health care technology developers. During the development and implementation process of ERPs, technology developers and implementation teams might adapt systems to the new work environment, in order to ensure a good fit. If health care personnel perceive incompatibility between the tasks to be performed and the new system, they might find it difficult to use and/or might find it useless. Implementation teams should create strong ties to potentially influential organization members who are ambivalent about the ERP system to provide the change agent with an affective basis in order to get an more intensive and positive coorperation (Battilana & Casciaro, 2013).

On the other hand, training processes might not only explain system use but also illustrate the ability of the ERPs to enhance job performance. Training processes should also be focussed to reduce the “resistance to be controlled” and the “perceived risks” by health care personnel.

The training process is one main vehicle for the dissemination of the organizational culture and should be directed toward reducing “resistance to change”, “resistance to be controlled”, and “perceived risks” in healthcare organizations. The training process should not only be focused to explain how the system works, but also to show the ability of information systems to facilitate daily operations, so that they are centered on spreading cultural factors in the organization. By using this strategy, the training process can be oriented to reduce resistance to be controlled and minimize the risks perceived to the use of these technologies.

Further research might investigate the importance of influences such as individual differences, prior experience, level of education, and the role of technology in organizations in the context of ERP acceptance in public hospitals.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.