This paper aims to analyze the online transparency of the top 100 Universities in the world and determine which factors influence the degree of online transparency achieved by these institutions. To this end, a global transparency index was developed comprising of four dimensions (“E-Information”, “E-Services”, “E-Participation” and “Navigability, Design and Accessibility”). From the analysis of the various dimensions, it is worth noting that universities are aware of the importance of having a web page with adequate “Navigability, Design and Accessibility”. In contrast, “E-information” is the least valued dimension due to universities focusing their attention on the disclosure of general information rather than on more specific issues. In addition, a multivariate regression equation was used to test the relationship between the online information disclosed and a particular set of factors. As main findings, younger universities of greater size and which are privately funded are the ones most interested in utilizing web pages.

Este trabajo tiene como objetivo analizar la transparencia online de las 100mejores universidades del mundo y, a continuación, establecer los factores que influyen en su grado. Para este fin se ha desarrollado un índice de cuatro dimensiones de transparencia global (“E-información”, “E-Servicios”, “E-Participación” “y” “Navegabilidad, diseño y accesibilidad”). A partir del análisis de las distintas dimensiones, se puede señalar que las universidades son conscientes de la importancia de tener una página web con una adecuada “navegabilidad, diseño y accesibilidad”. En cambio, “E-información” es la dimensión menos valorada ya que las universidades centran su atención en la divulgación de información general y no en cuestiones más específicas. Además, se ha aplicado regresión multivariable para comprobar la relación entre la divulgación de información online y una serie de factores. Como resultado principal se puede destacar que aquellas universidades más nuevas, de mayor tamaño y privadas son las más interesadas en el uso de páginas web.

Nowadays, the demand for transparency by universities is increasingly considered a fundamental part of the adequate accountability of these entities. Transparency can be defined as access to information regarding the intentions and decisions of the organization (Vaccaro & Madsen, 2009). Among the advantages that transparency provides to universities, Ricci (2013) highlights: (a) incrementing their legitimacy as professional entities that serve society, (b) avoiding bad management practices and, (c) facilitating public debate and participation regarding the strategic decisions of the university.

The Internet and, specifically web pages, are a practical medium for improving the transparency of universities as they are able to provide a wide range of information instantly to any user who requests it. Furthermore, it allows the creation of an interactive environment by providing different participation mechanisms such as forums and surveys, as well as offering teaching services via e-learning (Mondéjar, Mondéjar, & Vargas, 2006). Likewise, diverse authors state that web pages are strongly recommended to guarantee appropriate and accessible information to all stakeholders in an easy and cost-effective manner (Ojino, Mich, Ogao, & Karume, 2013).

Due to the importance of universities as crucial actors in the generation and transference of knowledge and the increasing demand for greater information access via web pages, previous studies have examined this issue in different ways: by analyzing the online disclosure of information of public universities (Flórez-Parra, López-Pérez, & López-Hernández, 2014); by focusing only on specific characteristics of university web pages like usability (Crawford, 2012); or by focusing on specific information content types such as social responsibility (Escobar, 2016; Rodríguez-Bolívar, Garde-Sánchez, & López-Hernández, 2013). Moreover, there is a greater tendency on analyzing the latest developments in specific countries from both the developed (Gallego-Álvarez, Rodríguez-Domínguez, & García-Sánchez, 2011) and developing world (Isfandyari-Moghaddam, Behrooz, Maleki, & Ranjbar, 2012). However, little attention has been paid to the need for providing a global overview of the question regarding the extent to which universities are committed to the need for transparency via an appropriate development of their web pages.

In this context, this paper presents two main objectives. Firstly the analysis of online transparency of universities and secondly, to identify the influencing factors on the degree of online transparency achieved by these institutions. In order to gain a global perspective of the possible trends, the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) has been chosen for the sample selection. In particular, the web pages of the 100 best universities in the world, according to ARWU, have been analyzed. The main outcomes show a moderate level of web transparency from the top universities as these entities give priority to general versus specific information. In addition, those younger, larger and privately funded universities are the most concerned with meeting the information needs of their stakeholders, using web pages to improve transparency.

The findings of this study aim to contribute to both the existing literature as well as to identify managerial implications to universities. Therefore, from an academic perspective, this paper seeks to contribute to the literature on the web transparency of organizations. Specifically, to expand the scarce literature focused on the higher education sector regarding the dissemination of information through the Internet and to examine the degree and type of voluntary information that universities share on their web pages. Therefore, the present study intends to advance in identifying trends and gaps that should be improved upon for the better use of web pages as a strategic communication channel. In addition, it can also provide fresh insights about the influencing factors that can lead to a greater use of universities’ web pages as a channel for improving information access, fostering participation and facilitating online services for their different stakeholders. Moreover, from a practical standpoint, the analysis of the degree of online transparency achieved by the top universities in the world could be used as a benchmark by other universities. Furthermore, the dimensions proposed can be used as guide for deans, department managers and teachers in order to make them more aware of the need to disclose information and also to specify or give guidance on how to go about it.

Theoretical framework and literature reviewAmong the diverse theoretical approaches related to information disclosure, legitimacy theory and institutional theory should be highlighted (Cuadrado-Ballesteros, Frías-Aceituno, & Martínez-Ferrero, 2014). Regarding legitimacy theory, Suchman (1995) posits that legitimacy is created subjectively as it strongly depends on the perception that the audience has of the organization. Likewise, the author argues that, “legitimacy management rests heavily on communication” (Suchman, 1995: 586). Moreover, institutional theory notes that in seeking legitimacy, organizations not only tend to respond to structural elements like the law but also to the specific requirements of their stakeholders (Meyer & Rowan, 1977).

Within this theoretical framework and focusing on the context of universities, previous studies highlight the need for transparency as they are under a high degree of public scrutiny due to their role in society as key actors in creating human capital and transferring knowledge at all levels (Hazelkorn, 2012). For this reason, it is important for these entities to provide information access and, in doing so, adopt communication channels that ensure an effective and efficient communication (Kirchner, Vasconcellos, João, & Alberton, 2016). Via an improvement in transparency mechanisms, such as web pages, universities can meet the expectations of investors, especially in the field of research (Hazelkorn, 2012); become more competitive in the recruitment of students and respond to established legal requirements (Castiglia & Turi, 2011). Hence, in general terms, a greater degree of transparency will reinforce universities’ legitimacy to key stakeholders be they students, parents, academic and administrative staff, ranking organizations, web agencies or the general public (Ceulemans, Molderez, & Van Liedekerke, 2015; Rufín & Medina, 2014). However, the mere adoption of a web page by any organization, including universities, does not guarantee its success, and thus the use of appropriate contents is indispensable in order to gain integrity, usefulness and clarity (Evgenievich, Evgenievna, Viktorovna, & Ivanovna, 2015; Isfandyari-Moghaddam et al., 2012).

The fostering of the university's transparency through web pagesThe majority of the literature regarding web disclosure in universities has been focused on the experience of a specific country (Crawford, 2012; Evgenievich et al., 2015; Kirchner et al., 2016; Ojino et al., 2013) or a region (Díaz-Nafría, Alfonso-Cendón, & Panizo-Alonso, 2015; Rodríguez-Bolívar et al., 2013). However, there is a scarcity of literature that addresses the global view of universities’ transparency by considering the top entities of the sector. Among the existing studies, there are those that examine stakeholders’ “perception” of the importance of web transparency (Evgenievich et al., 2015; Flórez-Parra, López-Pérez, & López-Hernández, 2016); those that examine the actual web transparency carried out by the university, albeit focusing on one specific dimension such as that related to the information that the web page contains (Al-Khalifa, 2014; Crawford, 2012; Escobar, 2016; Flórez-Parra et al., 2014), E-services (Kim-Soon, Rahman, & Ahmed, 2014) or E-participation (Díaz-Nafría et al., 2015) and those that take a more synthetized approach to various dimensions (Pinto, Sales, Doucet, Fernández, & Guerrero, 2007; Pinto, Guerrero, Fernández, & Doucet, 2009; Gallego-Álvarez et al., 2011). Hence, there is a need for studies that can provide a wide view of both a sample of top universities from different locations, and an analysis of all the aspects needed to guarantee adequate web transparency.

In order to respond to the increasing demand for online transparency and in line with the aforementioned studies, it is necessary to take into account four online transparency dimensions: E-information, E-Services, E-Participation and Navigability, Design and Accessibility (Al-Khalifa, 2014; Crawford, 2012; Díaz-Nafría et al., 2015; Flórez-Parra et al., 2014; Gallego-Álvarez et al., 2011; Kim-Soon et al., 2014; Ojino et al., 2013; Pinto et al., 2007, 2009; Rodríguez-Bolívar et al., 2013).

Delving further into each of the dimensions aforementioned, “E-information” refers to the inclusion of information on the Internet about the university. In this regard, authors like Rodríguez-Bolívar et al. (2013) stress that when disclosing information in universities’ web pages; both general information and specific information should be taken into account. With respect to general information, Crawford (2012) states that the universities should provide enrolment statistics, information on their facilities (buildings, sports, education, dining, etc.); while Al-Khalifa (2014) also stresses the relevance of giving information regarding job opportunities, university maps, how to get the university, new services and university publications.

With regards to specific information, there is increased interest in enhancing online information access related to “organization and governance”, “finances and management” as well as the “social responsibility” of the university (Escobar, 2016; Rodríguez-Bolívar et al., 2013). In relation to the information on the university's organization and governance, Gallego-Álvarez et al. (2011) state that society needs information about the principal actors that manage the university and, specifically, information regarding the Chancellor and Vice Chancellors. Moreover, Flórez-Parra et al. (2014) add that governance information related to the university's policies and regulations such as minutes of agreement and statutes should also be reported. Regarding financial and management information, Escobar (2016) states that universities should be more transparent in aspects such as information related to budget in terms of evolution of expenses intended for research, scholarships and grants; variation of noncurrent assets, links to annual accounts or costs of suppliers. Pertaining to social responsibility, Rodríguez-Bolívar et al. (2013) highlight that due to the social service that universities provide in aspects such as education and research, they should also show their concern for the economic, social and environmental impact of their activities.

There is growing demand for “E-services” that optimize the process of learning and administrative services in a more efficient and effective manner than manual processes (Ojino et al., 2013). Therefore, universities need to provide online alternatives such as downloadable forms and applications for administrative procedures, the handling of online administrative transactions and teaching by means of e-learning (Kim-Soon et al., 2014). Moreover, in line with Panopoulou, Tambouris, and Tarabanis (2008), not only is the assessment of the aforementioned services important, but also, the extent of such services, analyzing whether or not the entity offers the user the possibility of completing all stages of procedures and transactions, including payment, via their web pages.

Moreover, a university itself is a social system that needs to implement “E-participatory” democratic processes in order to obtain the involvement of their heterogeneous stakeholders (Díaz-Nafría et al., 2015). In this respect, Kim-Soon et al. (2014) point out the suitability of providing students a complaints or suggestions box, while Rodríguez-Bolívar et al. (2013) argue the importance of including discussion forums and chats on a university's web pages. Moreover, opinion surveys, blogs and contact information of professors are also considered quite useful for interactive purposes (Al-Khalifa, 2014). Likewise, Gallego-Álvarez et al. (2011) add the relevance of also disclosing the contact information of people in charge of services offered by the university and the option of being included on a mailing list to receive information as well as an email address for general information request.

“Navigability, Design and Accessibility” refers to the characteristics of the web page that make it possible for any user to easily navigate through the website. This means that anybody can have complete access to content, regardless of whether they have a disability (physical, intellectual or technical) or if the user encounters problems caused by technological or environmental factors (Panopoulou et al., 2008). To this end, the implementation of specific sections, the availability of information in different languages as well as the inclusion of a search system on the web page are recommended (Pinto et al., 2007, 2009). Furthermore, authors like Rodríguez-Bolívar et al. (2013) also stress the suitability of differentiating between internal links of the university and external ones to the wider Internet as well as the inclusion and design of a site map of the contents. Along these lines, Gallego-Álvarez et al. (2011) add others aspects like offering information in audio and/or visual format.

Explanatory factors of information disclosureThere is a vast array of literature concerning the determining factors of information disclosure. Among the most common organizational factors analyzed are organizational size (García-Sánchez, Frías-Aceituno, Rodríguez-Domínguez, 2013); age (Zeng, Xu, Yin, & Tam, 2012) and location (Sáez-Martín, Haro-de-Rosario, & Caba-Perez, 2014). In this respect, previous studies on universities have examined the importance of size, age and funding (Baraibar & Luna, 2012; Flórez-Parra et al., 2016; Gallego-Álvarez et al., 2011) albeit in the context of a specific country. Hence, it would be interesting to see if these factors also influence the online transparency of universities in a global context.

Looking at factors that are unique to the sector, it is worth mentioning that, in the higher education context, the quality of research, education and academic performance should be taken into account when analyzing motives that influence in the transparency decision making process (Hazelkorn, 2012). This is because these factors are key for the legitimacy of universities as professional agents that are focused on transference and generating proper knowledge for society. Hence, these factors can be strong indicators of universities’ interest in being more professional in their transparency policy. This is because, if they already have a “good image” as a result of their outcomes in terms of the quality of research, quality of education and academic performance, their stakeholders also could expect excellence in other aspects, including transparency. Thus, universities, in order to respond to such expectations, could also make web transparency a part of their strategy for building and reinforcing relationships with their stakeholders (Católico, 2012).

Based on these considerations, this study focuses on some common factors that have been considered in previous research in the context of the corporate and public sector as well as some factors that are specific to the higher education sector. Therefore, the determinants selected are the following: “organizational age”, “size,” “location” “private funding”, “quality of education”, “quality of research”, and “academic performance”.

Organizational ageGiven the demand for greater sustainability, efficiency and transparency (Ruíz-Lozano & Tirado-Valencia, 2016), older public sector institutions must use the disclosure of information via web technologies, not only to improve the visibility of their actions but also, as part of their differentiation strategy (Escamilla, Plaza, & Flores, 2016).

Concerning higher education, Gallego-Álvarez et al. (2011) and Garde-Sánchez, Rodríguez-Bolívar, and López-Hernández (2013a), both focusing on Spain and the United States respectively, consider that organizational age is a relevant factor that should be taken into account when analyzing the web disclosure of such entities. In line with this, Católico (2012) points out that age has a positive impact on web transparency in Colombian universities and that these institutions want to show their achievements over the years to the affected community. Likewise, focusing on social responsibility transparency, Garde-Sánchez (2013) pointed out that the oldest universities, which have a greater experience in running the organizations than their younger counterparts and are more likely to best implement their information communication policies. Hence, it would be interesting to observe the influence of this variable in the case of universities from a wider view. Consequently, first hypothesis propose is the following:H1 Age positively affects the web transparency of the world's top universities.

Size has always been considered as a factor that positively influences transparency, since the largest companies are the most exposed to public scrutiny and their management generates more interest among its stakeholders From different sectors such as the corporate (Fuente, García, & Lozano, 2017), public (García-Sánchez et al., 2013) and the NPO sector (Gálvez-Rodríguez, Caba-Pérez, & López-Godoy, 2012), organizational size has shown to have a positive effect on the online disclosure of information.

In relation to universities, previous studies have found that large universities are more willing to disclose information on their web pages in order to maintain their image for their wide audience. However, these findings are based on particular countries such as in the United States (Garde-Sánchez, 2013; Gordon, Fischer, Malone, & Tower, 2002), Spain (Gallego-Álvarez et al., 2011) and Colombia (Católico, 2012). Therefore, it could be convenient to observe whether the same results can be detected from a more global perspective. Taking these considerations the second hypothesis is the following:

H2 Size positively affects the web transparency of the world's top universities.

Previous authors have evidenced that location is a moderating factor in aspects related to voluntary disclosure of information (Khaled, Hichem, & Khaled, 2015). In relation to social responsibility reporting, location has a strong effect on disclosure policies (Bonsón & Bednárová, 2015), as the organization has to adapt the information disclosure programs not only to the legal requirements of the country but also to the demands of different stakeholders (Miras & Escobar, 2016). Furthermore, Bonsón and Flores (2011) and Sáez-Martín et al. (2014) state that the location of the organization influences the evolution of the use of web technologies as part of the communication strategy of the organization. Although differences from one country to another in terms of education have gradually become less extreme, there still exist differences between the policies and decisions taken by universities depending on where they are located (Flórez-Parra et al., 2016; Garde-Sánchez, 2013; Pinto et al., 2009). Therefore, it could be important to analyze whether the location of the university influences its decisions on supplying information via the web. Within this context, the sixth hypothesis is the following:H3 Location affects the web transparency of the world's top universities.

The main difference between public and private entities is that while private universities principally depend on students’ fees and private donations, public universities are mainly funded by the state (Gordon et al., 2002). With regards to funding, Gallego-Álvarez et al. (2011) argue that public universities should be more interested in disclosing information as they need to address political concerns to a greater degree than private universities. However, in their study on Spanish universities, the results were inconclusive. Moreover, Garde-Sánchez, Rodríguez-Bolívar, and López-Hernández (2013b) note that private institutions are the most interested in disseminating information on their websites in order to gain a competitive advantage because of the strong competition for limited financial resources.

Therefore, this study argues that private universities could be more motivated than public universities in being transparent, because the trust of donors and students can be very volatile and thus they could be under increasing pressure to meet the accountability expectations of their current and potential stakeholders. Taking these into consideration the fourth hypothesis is the following:H4 Private funding positively affects the web transparency of the world's top universities.

The quality of education systems is related to the implementation of mechanisms that show transparency in the decisions and processes carried out by these entities (Mamun, 2011). Furthermore, Larrán, López, Herrera, and Andrades (2012) argue that universities not only have to be the best in the transference of knowledge to students but should also be promoters of ethical values like integrity and transparency and, to do so, they must set a good example.

Authors such as Rodríguez-Bolívar et al. (2013) and Garde-Sánchez et al. (2013b) argue that it would be logical to expect that leading universities are also more willing to carry out online disclosure practices. These authors examine this question but concentrated on the information access to social responsibility and the results showed that the universities with greater prestige in educational quality were the most transparent. Similarly, Católico (2012) states that universities that achieve higher accreditations in educational quality are those who use the web to communicate their acquired positions to their stakeholders. In contrast, Flórez-Parra et al. (2016) find an inverse relationship between educational quality and web transparency. Therefore, it could be necessary to confirm whether this factor affects the web transparency of universities from a more global perspective. Within this context, the fifth hypothesis is the following:H5 Quality of education positively affects the web transparency of the world's top universities.

An aspect that is specific to universities is the achievement of high quality research, being one of the principal goals of universities, implying that the entity generates knowledge and innovation to society, which in turn enhances its reputation. In this respect, it worth mentioning that funding is one of the main ways to promote the best quality research (Sulo, Kendagor, Kosgei, Tuitoek, & Chelangat, 2012). Therefore, taking into account that web pages are part of the “external face” of the university (Hite & Railsback, 2010), this tool could be an excellent channel to disseminate the progress of the university's performance in order to cultivate its attractiveness to potential investors (Gallego-Álvarez et al., 2011). The same goes for doctoral students as the quality of research is part of the prestige they look for when choosing the university for continuing their studies. In this sense, the appropriate disclosure of information through the web pages could be an excellent recruitment strategy to attract and retain students and to enhance online accountability in general terms (Flórez-Parra et al., 2016).

Given these precedents, this study argues that those entities with the best quality research could be more willing to be more transparent via their pages as a part of their strategy to “show” the outside world the prestige of the organization. Therefore, the third hypothesis proposed is the following:H6 Quality of research positively affects the web transparency of the world's top universities.

Higher performing organizations are more interested in disclosing their financial information (Kundid & Rogosic, 2012) and non-financial reporting (Skouloudis, Jones, Malesios, & Evangelinos, 2014) as they enjoy a higher degree of trust from stakeholders and a greater demand for accountability (Lu & Abeysekera, 2014). The existing literature has shown that the performance of an organization, particularly that related to operational (Quayes & Hasan, 2014) and financial aspects (Frías-Aceituno, Rodríguez-Ariza, & García-Sánchez, 2013), has a positive effect on the disclosure of information.

Within the context of universities, a greater transparency may be related to the university's strategic plans and therefore to the institution's mission, which in this case would be excellence in research and academic performance. Academic outcomes is one of the performance indicators of greatest social interest and thus, there is increasing demand to know the progress made by the university (Flórez-Parra et al., 2016; Taylor, 2001). Consequently, it would be reasonable to expect that those universities with better academic performance are the most incentivized to use their web pages as a medium to inform their stakeholders that the entity has a strong commitment to academic excellence. Taking these considerations into account, the seventh hypothesis is the following:H7 Academic performance positively affects the web transparency of the world's top universities.

To carry out this study, the web page of the top 100 universities in the world based on the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU 2014) was analyzed between November and December 2015. This ranking is the result of a detailed study of more than 2000 universities around the world and, due to its solid and transparent methodology, is considered the most influential and widely-used international ranking system of its class (Goodall, 2006; Jabnoun, 2015).

The analysis of the top 100 universities could provide fresh insights about the trends in the sector, not only about the progress on the use of web page as an appropriate transparency mechanism, but also as a way to advance understanding of which factors influence the fostering of web transparency. In addition, there are few studies that have analyzed the dissemination of information via the web pages of universities from the global perspective (Flórez-Parra et al., 2014) and via using “leaders” of the sector, as defined by the criteria used in ARWU.

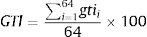

Research designThe research for this paper is structured in two phases. First, a content analysis was conducted to examine the information provided on university web pages. For Abbott and Monsen (1979) a content analysis is a very useful technique to collect information in order to codify qualitative information. According to Berg (2001) the type of content analysis implemented is deductive as the information is codified based on a disclosure index “Global Transparency Index (GTI)” which is composed of pre-defined subindexes derived from the online transparency dimensions identified in the literature reviewed (see Section “The fostering of the university's transparency through web pages”). In particular GTI is comprised of a total 64 items distributed into subindexes: E-Information (GTII), E-Services (GTIS), E-Participation (GTIP) and Navigability, Design and Accessibility (GTINDA).

As GTI is a numerical indicator with the aim of quantifying the amount of information that is disclosed (Gallego-Álvarez et al., 2011), a dichotomous scoring method was selected in line with previous researches that consider that an item's presence is not correlative with its importance (Wood, 2000) as well as with those with similar research objectives (Buenadicha, Chamorro, Miranda, & González, 2001). Thus, a specific item (gtii) was given a “1” if that information was provided on a web page and a “0” if it was not. Likewise, the subindexes were unweighted in order to obtain objective results in common with authors like Gallego-Álvarez et al. (2011). Therefore, GTI is determined by the quotient between the sum of all the item scores (gtii) and the total number of items observed (64 items). In order to express this in percentage form, this was then multiplied by 100.

The data was collected manually by two researchers working independently. There was an initial meeting to clearly set out the strategy for each indicator and then the results were reviewed at the end to solve any discrepancies and to overcome any possible bias. In particular, on completion of the coding, the results were compared and in those cases where there was no agreement on the score given to a specific item, a third person was consulted to decide what the assigned value should be. For instance, for item 14, the third person helped to clarify the discrepancies between coders and finally, that item was scored “1” when aspects of the education and work experience of the Chancellor and Vice Chancellors were disclosed. Therefore, the incorporation of the third reviewer improved the coding process and avoided errors of bias in the development of the GTI.

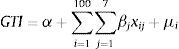

The second phase of research consisted of analyzing the influencing factors on the degree of online transparency achieved by universities. To this end, a multiple regression analysis was applied in line with previous authors such as García-Sánchez et al. (2013a,b). This is an appropriate technique to identify whether certain independent variables have predictive power or are explicative for a continuous dependent variable (Gatsi, 2016), particularly if certain common organizational factors and sector specific factors have explicative powers on the level of online transparency achieved by universities.

Taking all of this into consideration, the proposed model for the dependent variable is the following:

where α is the constant term, βj is the vector coefficient that is calculated, χi,j represents the variables that influence the information spread and μi is the random error, presumably with identical and independent distribution with an average of 0.Factors influencing the disclosure of the informationAccording to the literature review, seven independent variables have been deemed to be relevant to the level of web transparency (GTI) in the context of higher education. Four of these factors are considered to be common to both the public and private sectors and have been chosen based on prior research: the age of the institution (AGE), measured in number of years since its founding (Católico, 2012; Gallego-Álvarez et al., 2011); the size (SIZE) of the organization in terms of the number of students (Flórez-Parra et al., 2016; Marston & Polei, 2004); the environment or location in which the entity operates (LOC) has been another factor to take into account since there are many differences in the acceptance of transparency for the satisfaction of the requirements of the stakeholders, depending on the country or the region (Bonsón & Flores, 2011); and finally, the last determinant chosen was Financing (PRI), represented with a “1” if the university is financed with private funds or “0”, if the opposite was the case (Baraibar & Luna, 2012; Flórez-Parra et al., 2016).

Regarding the specific variables for universities, “Quality of Education” (Q.EDU) is measured as the percentage of Nobel Prize winning students and “Quality of Research” (Q.RES) is measured using the number of Nobel Prize winning employees, both in line with Goodall (2006). Pertaining to “Academic Performance” (A.PER), this was calculated as a percentage of the articles indexed in the Science Citation Index-Expanded and the Social Science Citation Index.

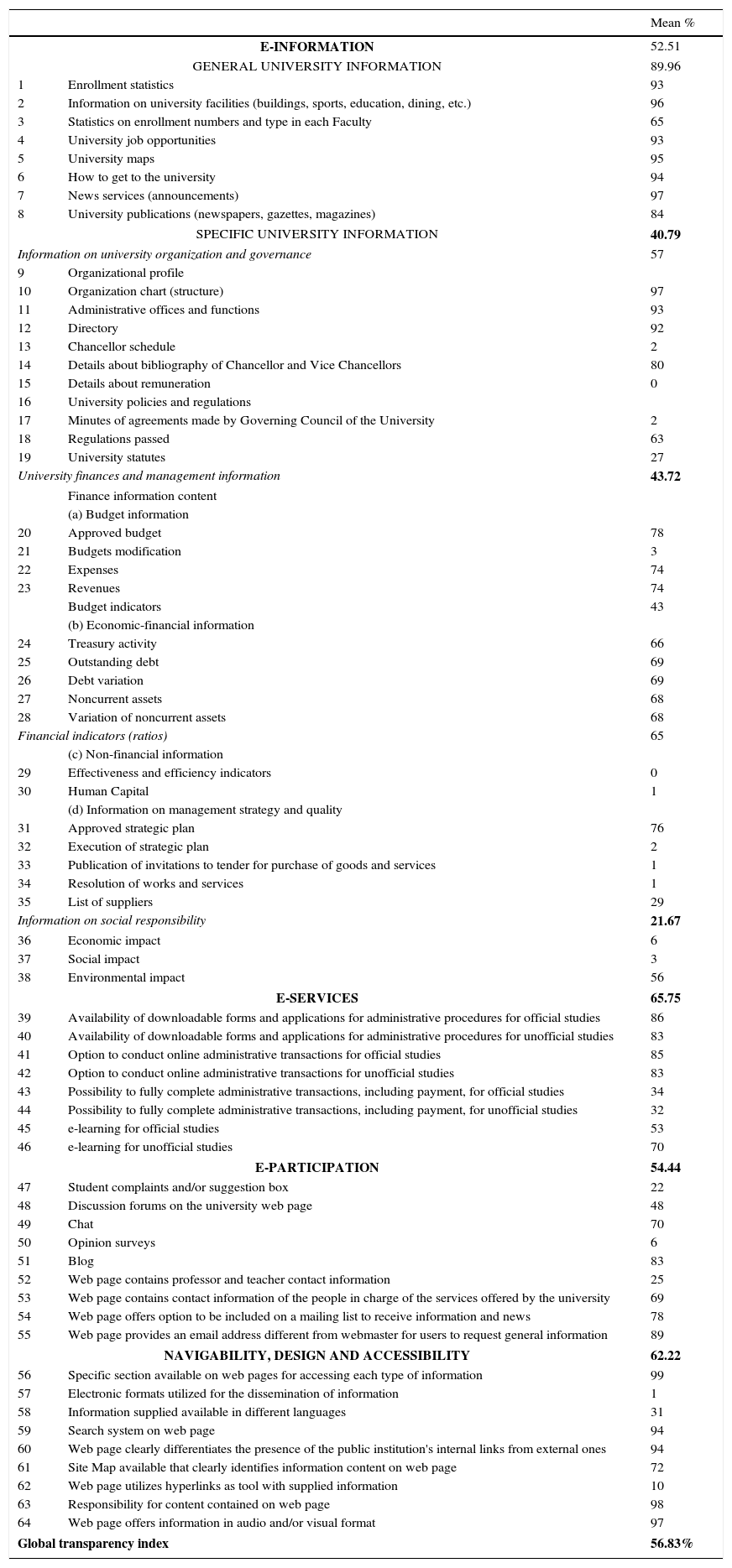

Results and discussionWeb transparency of universitiesThe analysis of university web pages obtained a global transparency level of 56.83% (see Table 1). Regarding the subindexes, it was observed that “E-services” and “Navigability, Design and Accessibility” reached greater values than “E-Information” and “E-Participation”. Hence, although transparency is considered as key for enforcing legitimacy and as a response to institutional pressure (Kirchner et al., 2016; Rufín & Medina, 2014), these entities still do not seem to consider it necessary to disclose relevant information and to set interaction mechanisms that ensure effective communication (Hazelkorn, 2012). As a result, universities understand that adoption of a web page is not enough (Evgenievich et al., 2015; Isfandyari-Moghaddam et al., 2012) and a moderate amount of information disclosure is, in general terms, the trend in the sector.

Results global transparency index.

| Mean % | ||

|---|---|---|

| E-INFORMATION | 52.51 | |

| GENERAL UNIVERSITY INFORMATION | 89.96 | |

| 1 | Enrollment statistics | 93 |

| 2 | Information on university facilities (buildings, sports, education, dining, etc.) | 96 |

| 3 | Statistics on enrollment numbers and type in each Faculty | 65 |

| 4 | University job opportunities | 93 |

| 5 | University maps | 95 |

| 6 | How to get to the university | 94 |

| 7 | News services (announcements) | 97 |

| 8 | University publications (newspapers, gazettes, magazines) | 84 |

| SPECIFIC UNIVERSITY INFORMATION | 40.79 | |

| Information on university organization and governance | 57 | |

| 9 | Organizational profile | |

| 10 | Organization chart (structure) | 97 |

| 11 | Administrative offices and functions | 93 |

| 12 | Directory | 92 |

| 13 | Chancellor schedule | 2 |

| 14 | Details about bibliography of Chancellor and Vice Chancellors | 80 |

| 15 | Details about remuneration | 0 |

| 16 | University policies and regulations | |

| 17 | Minutes of agreements made by Governing Council of the University | 2 |

| 18 | Regulations passed | 63 |

| 19 | University statutes | 27 |

| University finances and management information | 43.72 | |

| Finance information content | ||

| (a) Budget information | ||

| 20 | Approved budget | 78 |

| 21 | Budgets modification | 3 |

| 22 | Expenses | 74 |

| 23 | Revenues | 74 |

| Budget indicators | 43 | |

| (b) Economic-financial information | ||

| 24 | Treasury activity | 66 |

| 25 | Outstanding debt | 69 |

| 26 | Debt variation | 69 |

| 27 | Noncurrent assets | 68 |

| 28 | Variation of noncurrent assets | 68 |

| Financial indicators (ratios) | 65 | |

| (c) Non-financial information | ||

| 29 | Effectiveness and efficiency indicators | 0 |

| 30 | Human Capital | 1 |

| (d) Information on management strategy and quality | ||

| 31 | Approved strategic plan | 76 |

| 32 | Execution of strategic plan | 2 |

| 33 | Publication of invitations to tender for purchase of goods and services | 1 |

| 34 | Resolution of works and services | 1 |

| 35 | List of suppliers | 29 |

| Information on social responsibility | 21.67 | |

| 36 | Economic impact | 6 |

| 37 | Social impact | 3 |

| 38 | Environmental impact | 56 |

| E-SERVICES | 65.75 | |

| 39 | Availability of downloadable forms and applications for administrative procedures for official studies | 86 |

| 40 | Availability of downloadable forms and applications for administrative procedures for unofficial studies | 83 |

| 41 | Option to conduct online administrative transactions for official studies | 85 |

| 42 | Option to conduct online administrative transactions for unofficial studies | 83 |

| 43 | Possibility to fully complete administrative transactions, including payment, for official studies | 34 |

| 44 | Possibility to fully complete administrative transactions, including payment, for unofficial studies | 32 |

| 45 | e-learning for official studies | 53 |

| 46 | e-learning for unofficial studies | 70 |

| E-PARTICIPATION | 54.44 | |

| 47 | Student complaints and/or suggestion box | 22 |

| 48 | Discussion forums on the university web page | 48 |

| 49 | Chat | 70 |

| 50 | Opinion surveys | 6 |

| 51 | Blog | 83 |

| 52 | Web page contains professor and teacher contact information | 25 |

| 53 | Web page contains contact information of the people in charge of the services offered by the university | 69 |

| 54 | Web page offers option to be included on a mailing list to receive information and news | 78 |

| 55 | Web page provides an email address different from webmaster for users to request general information | 89 |

| NAVIGABILITY, DESIGN AND ACCESSIBILITY | 62.22 | |

| 56 | Specific section available on web pages for accessing each type of information | 99 |

| 57 | Electronic formats utilized for the dissemination of information | 1 |

| 58 | Information supplied available in different languages | 31 |

| 59 | Search system on web page | 94 |

| 60 | Web page clearly differentiates the presence of the public institution's internal links from external ones | 94 |

| 61 | Site Map available that clearly identifies information content on web page | 72 |

| 62 | Web page utilizes hyperlinks as tool with supplied information | 10 |

| 63 | Responsibility for content contained on web page | 98 |

| 64 | Web page offers information in audio and/or visual format | 97 |

| Global transparency index | 56.83% | |

Source: Own compilation.

These results coincide partially with previous authors that have examined a specific country, particularly with Gallego-Álvarez et al. (2011), who noted the need for greater effort in E-information by Spanish universities and Católico (2012), which highlights the lack of transparency in budgetary and financial matters in Colombian universities. However, this study's analysis does not share the conclusion obtained in others case studies that noted weaknesses in aspects related to the navigability of web pages (Pinto et al., 2009). Therefore, although the use of web pages as a strategic tool for information access is not fully utilized, the results of this study indicate a trend towards progress or improvement in web transparency.

Focusing on each subindex, “E-Information” presented an average value of 52.51%. Regarding general information about the university, the factors most extensively supplied online were related to the university's facilities (buildings, sports, education, dining, etc.) and university maps. With respect to specific information, online access to the university's governance and organization is highlighted. In particular 80% of the cases analyzed disseminated details regarding the bibliography of the Chancellor and Vice Chancellors and 97% of the universities analyzed published an organizational chart. However, it is worth mentioning that information regarding their remuneration was nonexistent.

Pertaining to financial and management information, it is important to highlight the disparate results obtained. While items related to treasury activity, noncurrent assets and financial ratios appeared in more than 60% of the universities studied, it seemed odd that hardly any of the universities provided data on budget modifications, strategic plans, or invitations to tender for purchase of goods and services. However, despite low transparency results obtained for certain aspects of finances and management, the indicator within this subindex that yielded the lowest percentage corresponded to social responsibility. Only 21.67% of the sampling provided information on the web pages related to social responsibility, and indicators for economic responsibility only appeared in 6% of these universities.

Analysis of the “E-Services” subindex revealed that it achieved an average value of 65.75%, making the items in this category the second most disclosed on the Internet. In terms of this information category, it is worth highlighting that 86% of universities studied offered downloads for applications and forms for handling official studies procedures. Nevertheless, despite these encouraging results, a complete online process that concluded with payment was only possible in 33% of all cases.

The “E-Participation subindex” presented a value of 54.44% on the total items. When analyzing this category, it was surprising to find that only 6% of universities offered opinion surveys online. Similarly, what is referred to as the complaints and suggestions box in this study also obtained a low score (22%), at least with respect to the online version. In contrast, it was noted that there was a notable presence of blogs, with a value of 83%, positioning them ahead of traditional discussion forums, which scored 28%, and chat rooms, which were available on 70% of web pages studied.

Finally, the subindex that corresponds to “Navigability, Design and Accessibility” registered the best results, achieving an average value of 66.22%. The item most used was the existence of a section used specifically to access each type of information, 99%. Likewise, most of the cases provided a search system on their pages and the internal links of the university are differentiated from external links. However, only few cases supplied their information in different languages (30%).

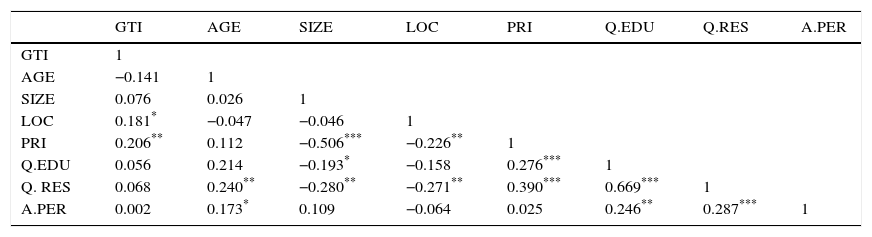

Results explanatory analysisThe second phase of this research consisted of studying the influence of specific independent variables on the level of online information transparency for universities. To this end, a multivariable regression analysis was utilized and, supposing that the variables in question possessed linear relationships, the Multiple Linear Regression was selected as the statistical technique. Nevertheless, Fisher's critical F value (F=3.162; Sig=0.006) allowed the study to confirm the existence of a significant linear relationship between the dependent variable and all of the independent variables.

Once the model's null hypotheses were confirmed (linearity, homoscedasticity, normality, independence and collinearity) and following the aforementioned methodological approach, a Pearson correlations analysis was conducted. This test revealed significant correlations between the variables of “size” and “public or private institution” and also between “quality of education and “quality of research” (see Table 2).

Correlations matrix.

| GTI | AGE | SIZE | LOC | PRI | Q.EDU | Q.RES | A.PER | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTI | 1 | |||||||

| AGE | −0.141 | 1 | ||||||

| SIZE | 0.076 | 0.026 | 1 | |||||

| LOC | 0.181* | −0.047 | −0.046 | 1 | ||||

| PRI | 0.206** | 0.112 | −0.506*** | −0.226** | 1 | |||

| Q.EDU | 0.056 | 0.214 | −0.193* | −0.158 | 0.276*** | 1 | ||

| Q. RES | 0.068 | 0.240** | −0.280** | −0.271** | 0.390*** | 0.669*** | 1 | |

| A.PER | 0.002 | 0.173* | 0.109 | −0.064 | 0.025 | 0.246** | 0.287*** | 1 |

Source: own compilation.

Regarding the Global Transparency Index, only a significant and positive correlation was observed for “public or private institution”. Despite the correlations found, in all cases the value detected was lower than 0.8, therefore in line with Neter, Kutner, Nachtsheim, and Wasserman (1996) these associations are not high enough to provoke problems of multicollinearity among these variables.

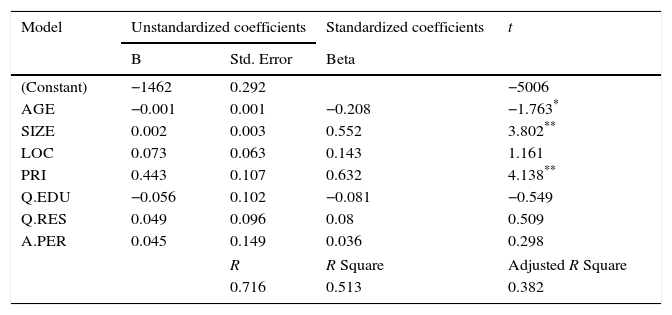

According to the analysis conducted (see Table 3), the explanatory capacity of the resulting model, which was measured using the adjusted R squared formula, was 38.20%, signifying that the adjustment was moderate. As for the typified regression coefficients, which help to value the relative importance of each independent variable in the equation, the following was found:

Results of regression.

| Model | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||

| (Constant) | −1462 | 0.292 | −5006 | |

| AGE | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.208 | −1.763* |

| SIZE | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.552 | 3.802** |

| LOC | 0.073 | 0.063 | 0.143 | 1.161 |

| PRI | 0.443 | 0.107 | 0.632 | 4.138** |

| Q.EDU | −0.056 | 0.102 | −0.081 | −0.549 |

| Q.RES | 0.049 | 0.096 | 0.08 | 0.509 |

| A.PER | 0.045 | 0.149 | 0.036 | 0.298 |

| R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | ||

| 0.716 | 0.513 | 0.382 | ||

Source: own compilation.

In relation to Hypothesis 1, results confirm that there exists a significant relationship between organizational age and the level of web transparency, however, the association found was negative (0.20; p<0.1). In other words, those younger universities are the most likely to supply online information. According to this, our result does not share the conclusions obtained in previous studies in the corporate sector (Larrán & Giner, 2002; Zeng et al., 2012) or in higher education (Católico, 2012). However, the findings are consistent with Lee, Pendharkar, and Blouin (2012), who pointed out that older organizations are more framed in their traditional environment and cannot apply the same techniques of accountability as younger institutions. In terms of universities this could be due to the universities with less experience being more aware of the importance of consolidating, their standing in the market via a greater development of their web pages.

Pertaining to Hypothesis 2, it was observed that university size was positively related to the transparency index (0.55; p<0.01). Thus, the larger the university, the greater the amount of online information contained in its web pages. This outcome is in accordance with previous studies that evidence the positive effect of this factor in the greater disclosure of information within the corporate sector (Fuente et al., 2017), the public sector (Garde-Sánchez et al., 2013) and the NPO sector (Gálvez-Rodríguez et al., 2012). Likewise, this finding supports those of previous studies about universities, albeit in the case of a specific country (Rodríguez-Bolívar et al., 2013).

Likewise, there were no relevant findings with respect to the association between the factor “location” (Hypothesis 3) and web transparency. This result does not coincide with previous studies related to voluntary information disclosure (Khaled et al., 2015) and those focused on Web 2.0 technologies in the corporate sector (Bonsón & Flores, 2011; Sáez-Martín et al., 2014). It seems, therefore, that the trend regarding the greater or lesser implementation of transparency best practices via the Internet is not a matter that is influenced by the cultural context where the university operates.

On the other hand, Hypothesis 4 was confirmed with the expected results indicating that private universities possess higher levels of online transparency than public universities (0.63; p<0.01). Therefore, while Gallego-Álvarez et al. (2011) could not confirm that public universities are the most interested in disclosing information via their web page it is argued here that, on the contrary and in line with Garde-Sánchez (2013) it is those entities that operate with private funds that are most likely to implement the advantages of this tool to disseminate information and strengthen links with their stakeholders.

Concerning Hypothesis 5, quality research also did not show a significant association with GTI. Thus, despite the fact that to maintain the quality of research in the university, external funding is necessary (Sulo et al., 2012) and although web pages have shown excellent advantages for fundraising purposes, as shown within the NPO sector (Waters, 2007), the results of this study indicate that universities apparently do not appreciate web transparency as an effective strategy for fundraising.

Academic performance (Hypothesis 6) did not affect the global online transparency of universities. Hence, while this factor has a positive effect on other performance aspects of the organization (Foyeke, Odianonsen, Aanu, 2015; Quayes & Hasan, 2014), university managers seem not to appreciate a relation between academic excellence and the best practices of transparency.

Therefore, quality of research, quality of education and academic performance are specific and relevant factors for a university's success (Hazelkorn, 2012) and the higher the ranking of universities regarding with regards to these characteristics, the greater the predisposition towards being more transparent (Católico, 2012). However, it seems that this influence is not as strong as to have a significant effect in the transparency policies of this collective.

ConclusionsPrevious studies have pointed out the importance of “E-information” (Crawford, 2012; Gallego-Álvarez et al., 2011), “E-Services” (Kim-Soon et al., 2014; Ojino et al., 2013), “E-Participation and Navigability” (Rodríguez-Bolívar et al., 2013) and “Design and Accessibility” (Pinto et al., 2007, 2009) for an appropriate fulfilment of online transparency. This research highlights that universities do not give the same importance to all aforementioned aspects. In particular, there is a high level of interest in “Navigability, Design and Accessibility” followed by “E-Services” and to a lesser extent in “E-Participation”. Regarding “E-information”, this dimension obtained the lowest score. Hence, it seems that universities understand the relevance of disclosing general information but they still do not value the importance of responding to the growing demand for specific information regarding organization structure, governance, management and financial information, with information related to social responsibility being the most undervalued.

By analyzing the world's top universities, this study also provides greater consistency to the results obtained in previous researches developed in within other specific contexts with regards to the predictive power of “organizational age” (Católico, 2012), “size” (Gallego-Álvarez et al., 2011; Gordon et al., 2002) and “private funding” (Garde-Sánchez, 2013) in the levels of web transparency in universities.

In this regard, results obtained indicated that younger universities are the most interested in using web transparency as a strategy to improve their competitive position, particularly via the acquisition of information technologies, which are demanded by their stakeholders. Likewise, those with greater size, which are the most subjected to public scrutiny, are the most willing to use this mechanism as a channel for rendering accounts and improving services. On the other hand, funding has been a notable driver of the use of web pages in this respect, indicating that private universities are the most committed to exploiting the advantages of web pages as a medium for improving the dissemination of information, participation and delivery of services in a proper and accessible manner to their stakeholders. These results are explained under the legitimacy theory lens that highlights that organizations are interested in using those mechanisms that help them to obtain social approval on their intentions and decisions. It also speaks to institutional theory that notes that organizations try to reinforce such legitimacy via the implementation of those mechanisms that truly match the expectations of stakeholders, such as the use of information and communication technologies.

The outcomes of this study can contribute to both the existing literature and practitioners. From the academic stand point, the findings advance in the better comprehension of the aspects that should be considered when analyzing the full potential of web page as a transparency mechanism. In addition, it augments the limited literature that specifically examines the motives that stimulate online transparency in universities and particularly considering a global view taking into consideration universities from other countries and “leaders in the sector” which in turn could also serve as an indicator of the trends of this collective.

From a practical point of view, the results present implications for university managers as these findings can serve as relevant information about the trends in the sector and as a benchmarking technique for similar organizations of this sector, specifically to help them analyze their position on this matter and consequently to identify possible improvements. Moreover, taking into account the explanatory analysis, those entities with more experience should not rely on their current “position” and should be very aware of keeping up with the dynamic demands of the market. Likewise, smaller universities should place greater value on the advantages that web pages provide as a cost-effective tool for growing the organization. In addition, those universities with a public profile should be more interested in the importance of using those technologies that allows them to enhance their image and the quality of their organization. Furthermore, the dimensions proposed can be used as a guide for deans, department managers and teachers in order to demonstrate how they could implement transparency policies in their own faculties and thus be active actors in fostering web information access to key stakeholders of the academic community.

Although this study presents valuable findings, the current study is not without its limitations. This study provides a view of statistical relationships between certain predictor variables and online transparency. Hence, to prove a causative relationship, this data should be theoretically and empirically explored in future researches. Furthermore, the opinions of both the management and staff of universities in relation to the main obstacles and barriers to using web pages as a transparency mechanism is underexplored. Likewise, it could be very valuable to carry out studies that encompass the opinion of the universities’ stakeholders about what they consider to be the most important information that should be disclosed via web pages. Moreover, the variables analyzed in this study are limited, therefore, expanding the analysis not only to other internal factors but also to those external factors related to the environment in which they operate could prove fruitful in future researches.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.