The present paper deals with one of the most neglected areas of research in accounting, that of the Army. In spite of the literature on industries related to the Army, not too much has been extended on the Army per se. For this reason, this paper analyses the process of rationalization developed in the 18th century in Spanish Army Hospitals, as a result of the bankruptcy of the Royal Finances. Due to this process, the Military Hospitals were the most developed in the country, and it led to the emergence of the Contralor (Controller) within the hospital, and thus accounting was considered as an essential matter.

El presente trabajo analiza una de las áreas menos desarrolladas de investigación en contabilidad, como es la contabilidad en el Ejército. A pesar de la cantidad de literatura en relación con industrias asociadas al Ejército, es escasa la porción dedicada al Ejército per se. Por este motivo, este trabajo analiza el proceso de racionalización desarrollado en el siglo XVIII en los Hospitales Militares en España, como resultado de la suspensión de pagos de las Finanzas Reales. Como resultado de este proceso, los Hospitales Militares se convirtieron en los más desarrollados del país y supusieron la aparición del rol del Contralor (Controller) dentro del hospital, considerando así a la contabilidad como un elemento fundamental.

Management accounting innovations on military institutions have been studied, from a historical point of view, mostly related to industries (i.e., Fleischman & Tyson, 2000; Hoskin & Macve, 1988; Lemarchand, 2002; Tyson, 1993). In fact, an interesting debate at the development of accounting at many industries was embedded on a military institution as the West Point Academy at the US (Fleischman & Tyson, 2000; Hoskin & Macve, 1988, 2000; Tyson, 1993). From this debate, and regardless of the perspective used for such analyses, the methods and systems developed at such institution were the genesis of fresh, and not used previously in private business, management accounting methods (Funnell, 1997). In the same way the emergence of the interest at the United Kingdom for the cost accounting and the wide spread of such technique and its shift towards the standard cost at the society in general were deeply rooted in a military basis, and, specifically, on the industries at the First World War (Loft, 1993; Miller & O’Leary, 1987).

However, it has been scant the literature on the genesis of innovative management accounting techniques at the military institution by itself, that is, not centred on the industries (public or private) related to military (Funnell, 2005, 2009). Interestingly, such gap on the sources for innovation at management accounting methods at the Army can be engaged on the subsequent debate that lays out at the previous studies. In this sense, the West Point Academy led the flow of management accounting techniques from the Army to the private business (Hoskin & Macve, 1988). Yet, Lemarchand (2002) found that the techniques used at private business were translated to the war institutions by resorting to military engineers. In a similar vein, Zambon and Zan (2007) pointed out to the government as the promoter of a complex system of accounting records established at the Venetian Arsenal in 1586.

Some reasons can emerge for the implementation of accounting techniques at military institutions. Firstly, it could be an economic crisis (Funnell, 2009). A crisis could explain a change in a given status quo (Lemarchand, 2002; Zambon & Zan, 2007). In other cases, it was a consequence of the implementation of new politics on other arenas, as a social programme, which required from public resources. That could suppose fewer resources for the Army, and so, the leading of management towards the emergence of new accounting techniques for the control of the military expenses (Funnell, 2009). It should be remarked, too, those cases rooted on wars and the management of war, from an ideological point of view (Fernández-Revuelta, Gómez, & Robson, 2002), or for the rationalisation at the management of the war, which, in some cases, did not lead to good results (Chwastiask, 1999, 2001, 2006). Finally, the disasters at a war could lead to a political crisis being accounting finally installed at the Army (Funnell, 2005).

Consequently, this paper analyses the design and emergence of the Reglamento y Ordenanza que deben observar los Ministros y Empleados en los Hospitales para el Ejército (Instruction for Military Hospitals). This regulation was sanctioned by the Spanish king Philip V on 8th of April, 1739 (Riera, 1992). The reasons to understand the emergence of this Instruction can be found on the Spanish Decree of Bankruptcy previously sanctioned on 21st March, 1739 (Fernández, 1977). This Decree supposed the stopping of all the payments from the Royal Treasury and the appointment of a new Minister for the Royal Treasury that faced up the needed reforms to improve the public finances. The crisis of the Royal Treasury was so high that the expenses were a third higher than the incomes (Fernández, 1977). Interestingly, the Army expenses represented three parts of four of the total amount of the state expenses (Fernández, 1977).

The control over the Army expenses was stated as a main issue of the Instruction for Military Hospitals, but it was not the only one (Corpas, 2005; Puell, 2008). It comprised all the matters that should be considered at a hospital at such time (Arcarazo & Lorén, 2008). As a result, the Instruction for Military Hospitals represented the main regulation on military hospitals for more than a century (Riera, 1992; Vega, 1988). The rule is based on three main pillars: (i) the most important aim of a hospital was the quick recovery of the ill soldiers; (ii) for this aim, it was needed to bring up to doctors, druggists, or nurses, through teaching; and (iii) the administration of a hospital must be a main issue and all the resources should be controlled (Puell, 2008). For these reasons, military hospitals suffered a huge change that led them to keep “…a network of services and a hospital management up to the rest of hospitals during all the century…” (Riera, 1992, p. 13).

From the accounting point of view, the Instruction for Military Hospitals implied a complex net of flows of information where the Contralor (Controller) was the main receiver and sender of this information. The Instruction for Military Hospitals is interesting on the control over the resources and stocks, the control over the daily stays of the ill military men and the requirements for the management of a hospital that led to a hard control over the rooms, medicines, equipments, tools, kitchen, food, wardrobe and so on, which was detailed sharply at the Instruction. Interestingly, the most of the costs of a military hospital were refereed to the daily stay of an ill person (distinguishing between officers and ordinary soldiers), being this last the main resort of the complex mechanism of control of a hospital (Corpas, 2005; Teijeiro, 2002; Vega, 1988).

From this analysis, it is expected to contribute to the literature by expanding the ability of a political crisis to engage in a huge reform at a military institution which reached far from the mere reduction of costs at hospitals and made accounting key element for the distribution of works and the design of the posts at the organisation. Accounting and control procedures at military hospitals defined the different posts and tasks. Accounting, thus, was able to constitute the roles at the organisation. Accounting, by the same way, was adapted to fulfil the aims of the military hospitals. In accordance with Funnell (2009), military hospitals became a problem of resource management amenable to the discipline of accounting. Thus, “…accounting was densely interrelated with a particular way of delineating tasks and roles…” (Miller & O’Leary, 1987, p. 41), showing so, how accounting has a constitutive role at the organizations.

This work has resorted, mainly, to primary sources. All of them are located in the General Archive of Simancas (AGS). The most of the sections analysed for this work are not catalogued and detailed yet. In the same way, it also has considered secondary sources to complete and verify the information supplied by the primary sources.

The rest of the paper is as follows. The next section will describe the previous ideas of hospitals management to the enactment of the Instruction for Military Hospitals in 1739, with a special reference to the reasons and consequences for the sanction of the Decree of Bankruptcy. The third section will be devoted to show the main issues raised by the Instruction for Military Hospitals. The fourth section will explain the accounting flows at hospitals. Finally, it will be drawn the analysis, conclusions and future research of this work.

Background of the Instruction of 1739The Instruction for Military Hospitals did not emerge as a surprising and unexpected regulation for the management of hospitals of the Army. According to Massons (1994), in 1708, the king Philip V sanctioned the Instrucción que se ha de observar para el buen Gobierno de los hospitales (Instruction for the good management of the hospitals). Given that many military hospitals were managed by private businessmen, a key issue was the cost of these establishments for the Royal Treasury. Therefore, this rule emphasized the control over the stays of the individuals, with penalties for those managers that made frauds at their accounting books. Each ten days the managers must send a list of the ill people at the hospital. In the same way, the doctors must fulfil a document with the number of ill people by their illness, which would be sent each ten days to the Ministry of the Royal Treasury. Without this information the doctors would not be paid. A Controller must verify the number of ill people, as well as their foods, medicines and so on according to the doctor's orders. Such verification allowed the hospital for sending to the Accounting Office of the Army reports on the number of ill people to be paid (Massons, 1994).

The lack of uniformity in the application of the instruction of 1708 led in 1721 to enact a new Instruction (Raquejo, 1992; Riera, 1992), called simply Ordenanza sobre Hospitales (Ordinance about Hospitals) (AGS, Guerra Moderna, Sup., box 269). This new regulation added (and it was focused on) more details about aspects such as surgery times, the delivery of foods and medicines, the portion of foods and the composition of such food and the control over the resources at the kitchen. Finally, it also disposed the need that the Superintendent of the Army should sign several forms of the managers to be paid in those cases where the management of a hospital was lent.

The surrounding concern on the expenses for military hospitals can be found on many studies. One of the most interesting, dated in 1735, is refereed to the military hospitals of Aragón and Cataluña, due to several problems of the Royal Treasury with the businessmen that managed these institutions (Riera, 1992). In such study, the author made a comparison of the costs and the amount paid by the Royal Treasury for a daily stay of an ill person due to maintenance, beds and firewood. He obtained that the lenders got a profit of 534,000 reales per year, which, for eight years of leasing, meant near to 4,300,000 reales of profit. In this way, the author concluded on the need that the Royal Treasury should manage the hospitals by its employees. With this measure there would be a cost saving for the public finances (AGS, Guerra Moderna, box 2409). Later, the experience should show that such idea was not successful, with many hospitals being lent (Puell, 2008).

But a most influential reason for the re-ordering of the military hospitals in Spain and its colonies can be found on the Decree of Bankruptcy of March, 1739. A main feature of all the kingdom period of Philip V was the surplus of the expenses over the incomes of the Royal Treasury. According to Fernández (1977), in 1713 the total amount of incomes represented the 45% of the expenses. In 1726 these amounts were closer, but the incomes did not reach the expenses, representing a 72% of the total amount of those.

An explanation of these deficits can be found on the Army expenses, due to the wars and, in many cases, based on the aim of the King to expand the empire for his offspring (De Castro, 2004; Puell, 2008). Thus, the different Ministries of the Royal Treasury urged the King to solve these problems, but in many cases he did not stop the belligerence of the Army to expand his Spanish empire. In fact, in 1737, the Ministry of the Royal Treasury advised to the King on the need to make a tighter control over the expenses of the Royal House and those of the Army and a cut on all the payment of the debt until the end of 1736 that has not been satisfied at all yet (Fernández, 1977). These requirements could not be fulfilled, firstly, because of the absolute power of the King was not subjected to the Royal Treasury Minister restrictions and secondly, because of the enemies that Spain had in that time (mainly England) could not prevent for spending at the Army. In spite of all the claims, at the beginning of 1739, the King had already assigned the whole incomes of 1739 and those of 1740 for the accrued debt. Thus, due to the lobby of the absence of liquidity at the Royal Treasury, the 21st of March, 1739 the King sanctioned a Decree of Bankruptcy of the Spanish Crown.

The change on the mentality towards a higher control over the expenses can be understood only by resorting to the consequences of such Decree. The most important was the change on the Royal Treasury Minister (De Castro, 2004). The new Minister took into practice all those reforms aimed to solve the problem of the public finances that the previous ministers could not undertake (Fernández, 1977). Among these reforms, the change on the management of the military hospitals was one of them, and the way to implement it was the Instruction for Military Hospitals of 1739.

The Instruction of 1739. An overviewThe 1739 Instruction for Military Hospitals meant a gap with the previous regulation in the management of military hospitals. Because of the insistence of the Bourbon dynasty on the improvement of military hospitals during the most of the beginning of the 18th century (Arcarazo & Lorén, 2008), “[t]he Instruction for Military Hospitals of 1739, consists on a collection of dispositions that, for the first time, regulates in an exclusive and systematic way, the running of this Service” (Corpas, 2005, p. 185). The control over the resources that it supposed departed from a main idea: to define and standardise the activity in a hospital in such a way that the control over it could be as higher as possible (Corpas, 2005; Riera, 1992). This aim was fulfilled by the Instruction for Military Hospitals, a book of 186 pages, divided in three Treatises and four regulations (Corpas, 2005). The Treatises dealt with the management of a hospital located in a town (which comprises 137 articles in 46 pages), also called quartered, the management of a hospital in the battlefield (which comprises 165 articles in 56 pages), also called campaign hospital, and a final Treatise on the different reports that should be signed by the Director and approved by the Controller of a hospital. It includes a description on how to construct them and a template for each one, it is not ordered in articles, and it has 84 pages. The regulations are specific to the food rations of all types, classified for ordinary soldiers and officers, the activity of the War Commissioners as inspectors or Directors at hospitals and the Intendants of the provinces (Corpas, 2005). All the hospital armies, including those of the Royal Navy, should be run according to this Instruction (Raquejo, 1992; Riera, 1992).

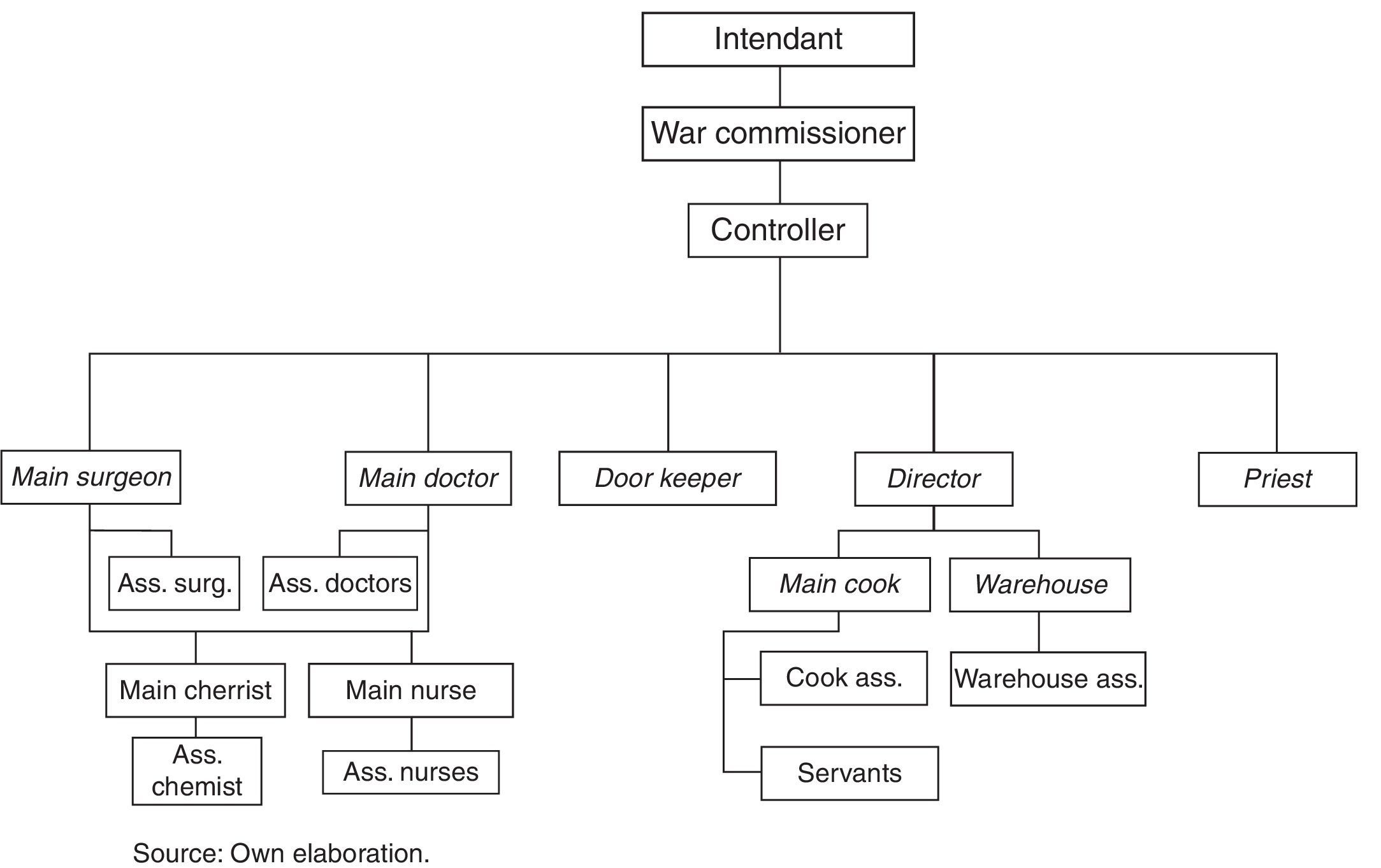

Organizational structureGiven that the new Instruction encompassed all the posts at a military hospital, it described all the posts and their duties. The new Instruction meant a definition of the posts in military hospitals and an organisational structure not described in the previous regulations (Riera, 1992). For this aim, it can be considered in Fig. 1.

As it can be stated, the Intendant of the Army was the highest authority of military hospitals: “… The Intendant… that sets… Agreements for the support of the hospitals… must apply the most of his care… to the clearness of the Conditions…” (Instruction for Military Hospitals, 1739, p. 184). This one, normally, appointed a War Commissioner for the most of verification of the activity: “[The Intendant]… will station the War Commisioner or Commisioners that must have the inspection of the Hospital…” (Instruction, 1739, p. 184). In each hospital, the Accounting Office of the Army appointed a Controller as the highest responsible for the control of the management of the hospital (arts. I–XXII, 1st Treatise). The location of the Controller at the higher levels of the organisational structure is not new, given that the Bourbon dynasty and their governments had a persistent interest on the rationality and the control (see Carmona, Ezzamel, & Gutiérrez, 1997; Sarrailh, 1992). From the Controller, the activity of a hospital was divided in two main areas: One, on the medical staff, with Doctors, Surgeons and Chemists (art. XLVI, 1st Treatise; art. VIII, 2nd Treatise) and another one on the stores and kitchen of the hospital managed by the Director in those cases of lent hospitals (Instruction for Military Hospitals, 1739, p. 104). As Corpas points out, “…the post of Director is accountable… to the permanent control of the Controller” (2005, p. 187). Finally, the organisational chart is defined by a Doorkeeper (arts. XXIII–XXV, 1st Treatise) for the control of the admission and exit of ill people, and a Priest (arts. XXVI–XXXVI, 1st Treatise). Thus, the organisational chart was a response to the aims of a military hospital to recover, as soon as possible, to soldiers for the needs of the Army, and, overall, with a huge control over the resources spent.

The standardization of the processesThe Instruction for Military Hospitals described the activity for the different posts, in some cases, with a high detail, and with the aim of an exhaustive control over the resources. For example, the article VI of the First Treatise, describing the activity of the Controller, explained: “…[at] two o’clock will be back at the Hospital in order to observe if something has to be solved, and he will do the same as in the morning, regarding to inspect the Kitchen, watch for news at the Warehouse, verify the right weight of the food rations for the dinner, with the same rules and circumstances that he filled out for the lunch, for the best assistance to the ill people…”.

The Instruction for Military Hospitals was also concerned on the bringing up of new Doctors, Surgeons and Chemists. Due to this, for example, the art. LIV of the First Treatise disposed that every day all the Assistant Doctors should discuss for, at least, an hour about all the cases at their departments explaining their solutions to the Doctors being this a way to improve their knowledge and skills in order to be appointed as Doctors or Surgeons.

The Instruction for Military Hospitals detailed how to proceed and how many visits to make to the ill people, how and when to describe the medicines at the forms to be filled (First Treatise, arts. XXXVII–XLI); the Instruction that must be followed for the food rations (First Treatise, art. XLII; see also The Instruction for food distribution, 3rd Treatise) or the control that must do the Doctors over the Chemist. In this sense, the article XLV of the First Treatise explained: “… [the Doctor] will care specially to watch for the Pharmacy, and verify if the delivered medicines are the same than those prescribed, in order to observe if the Chemist is making a default of deliver some medicines instead of others, given that these practices must not be done without their approval [of the Doctor] and they [the Chemists] must report on those [medicines] missed, and so he [the Doctor] will not prescribe such medicines until the Pharmacy is supplied on them…”.

The detailed prescription of the tasks and the organisational chart led the hospitals to a standardised activity, performed according to the Instruction for Military Hospitals. In this way, the standardisation of the activity would be guided to complement the control over the resources and, overall, the control over costs of the hospital and the internal procedures.

The internal control and proceduresThe control of the resources, ill people, medicines and employees at a military hospital was classified at the Instruction depending on the location of the hospital: in a town or in a battlefield. This last comprised more information and detail than the first one, considering the uncontrolled variables that can appear at a conflict, far from the troops located in a defined area or town and not related to such warfare.

Information at the town hospitalThe regulation about the information flows was described along the Instruction for Military Hospitals in its First Treatise by each of the posts described. After a careful analysis of the Treatise it can be stated that the items to be controlled could be classified in four areas: control over the resources; control over medical activity, control over ill people and over employees.

Regarding the control over the resources, Fig. 2 would help to explain the information flows. The Controller is the main receiver and sender of information. Thus, the Warehouse sent a daily report to the Controller with the amount of food rations distributed to the ill people (art. CXIV, First Treatise). Also the Chemist sent to the Controller another report on the needed medicines that should be bought for a hospital (art. LXXVIII, First Treatise). Interestingly, the Controller had also “… to send a report to the War Commissioner…” on the food in bad condition that should be destroyed (art III, First Treatise). In the same vein, the Surgeon must settle with the Warehouse the charge by the resources used at the cures of the ill people on a monthly base (art. LV, First Treatise), and the Warehouse had to receive from the Nurses a charge for the sheets not returned there (art. XCIX, First Treatise).

Concerning to the control over the medical care the Controller was, again, the main receiver and sender of information (see Fig. 3). Consequently, the most of the information is interchanged with Doctors and Surgeons. So, the Controller received daily information from the Doctors about location and number of those worse people due to their illness (art LXII, First Treatise). By the way, for every four months, the Controller allowed the War Commissioner to inspect the Warehouse (art. XI, First Treatise). The Controller must deliver to the Doctors and Surgeons the ordinances about food rations, which explained the amount and features of food for the ill people at each food time (breakfast, lunch or dinner) and must be fulfilled by the Doctors as Surgeons (art. LXII, First Treatise). Daily, the Doctors and Surgeons disposed the food and medicines for the sick and this information was sent to the Cook and Chemist, respectively (art. LXII, First Treatise). Also, the Chemist must prepare the ointments and balms disposed by the Surgeons on their forms (art. LV, First Treatise).

The control over the sick was a main issue at a military hospital, and so, the Controller, again, was the main receiver and sender on information about them (see Fig. 4). In this way, the Controller, had to run a book on the ill people, the number and room where to locate them, their post and the Army where they belonged (art. I, First Treatise). Daily, this information was updated. The entrances were delivered to the Controller by the Doorkeeper. Each month the Controller must send to the Accounting Office of the Royal Treasury and the War Commissioner a form containing all the information about the ill people (see Fig. 5). The Controller also had to send to the Warehouse a form with the uniform, weapons and personal belongings of the soldiers at their entrance at a hospital to keep them (art. XX, First Treatise). Finally, the Controller was the one to approve the discharge of the recovered soldiers for their exit (art. XIX, First Treatise).

Finally, the Controller was responsible for hiring or the dismissal of employees, and so, the matters with Surgeons, Doctors, Nurses, or Chemists must be reported to him (art. XVII, First Treatise). Curiously, the Priest must report to the Controller on the Christian not or disordered behaviours.

Information at the campaign hospitalThe campaign hospital, given its larger size and the urgency of its works in the battlefield, differed from a town hospital but the most can be applied for this case. The information flows, in this case, are described on the 2nd Treatise. In this sense, the main differences are focused on the increase of control over the resources, the medical care and the employees. The control over the resources was reinforced with a report made by the Warehouse to the Controller with all the tools, equipment and goods received, which must be sent by the Controller to the Army Intendant, “… making an exact and clear report, in such a way that the Minister [Intendant] knows everything…” (art. I, Second Treatise). The Warehouse must keep a book with the changes on such items. Regarding the medical care, Doctors must deliver to the Controller a form with the needed medicines. Daily, information about the ill people was sent from a Room Commissioner to the Controller for the updating of his book about the ill people. In the same vein, the Room Commissioner sent, daily, a form with the food rations to the Warehouse, and a report on the death people. When asked for it, the Chemist must sent to the Controller a form with the medicines delivered to the ill people, those in bad condition and destroyed, the balance of each one, and those sent to other hospitals. Daily, the Doctors and Chemist must verify their books to agree in the amount of medicines delivered to the ill people. Finally, as in town hospitals, the Controller received information from the Doctors and from the Priest about any bad behaviour of employees that should be dismissed and sent this information to the War Commissioner. The Doctors reported to the War Commissioner on the need to dismiss any Assistant Doctor or to ask for the improvement of the number of Doctors when needed.

Forms and reportsThe most of the information was used to make official reports that the Instruction for Military Hospital disposed. In this sense, as part of his work, the Controller verified and approved, or not, the information that a military hospital must sent to outside on: Purchases of goods, food, medicines, equipments, clothes, goods and food in bad condition, delivery to other hospitals of goods, food, medicines, on the entries of medicines, freights and, overall, the monthly reports of food rations by soldiers and officers (see Figs. 4 and 5). Specifically, for those hospitals lent to private businessmen, the people appointed to be Director managed such hospitals by themselves, but for all the previous information the Director must receive the approval of the Controller.

Due to the information flows at a hospital, it can be stated that “…the controller, at the end, is the head of all the services [at the hospital] as far as this word can go: doctors, surgeons, assistants, nurses, chemists, […] all of them are under his inspection and his authority and influence…” (Teijeiro, 2002, p. 263).

Analysis and conclusionsThe main base of this study can be found on the lack of studies on military institutions from a historical point of view (Funnell, 2005, 2009). The literature has thrown light on how accounting techniques emerged from associated institutions or episodes to the Army, as the war, or due to the spread and widening of accounting techniques towards the management of a population. Being the military expenses a target of a relative weight at the public sector finances, it is interesting to focus on the emergence of accounting techniques at the Army institutions (Funnell, 2009).

In this way, this work has dealt with the analysis of the Instruction for Military Hospitals of 1739 enacted by the King Philip V on 8th of April as the result of a Decree of Bankruptcy disposed by himself on 21st of March, 1739. The Instruction for Military Hospitals did not emerge automatically. Since the beginning of the 18th century, the control over the military institutions was gradually increased (Baños & Gutiérrez, 2011) and the hospitals were a main target (Riera, 1992). Like this, two previous instructions to the Instruction for Military Hospitals tried to rule the activity and control over resources at the hospitals (Corpas, 2005; Massons, 1994; Puell, 2008). Also, studies on the management of a military hospital by the civil servants reflected a concern on the expenses that military hospitals supposed.

But finally, the Decree of Bankruptcy of March, 1739 meant the allowance towards a regulation on the management of military hospitals as a whole. Such Decree supposed a governmental crisis, with a change on the government members, and, specifically, on the Minister of the Royal Treasury (Fernández, 1977). This change was not only on the person appointed as Minister, but, overall, a change on the mentality of making smooth reforms from the government (Fernández, 1977). In this sense, the appointment of the new Minister meant the movement towards deep reforms which could lead to solve the lack of resources of the Royal Treasury (Fernández, 1977). A main target on the control over the expenses was the Army. Following Funnell (2009), a governmental crisis led to a change into accounting techniques applied to Army institutions. Interestingly, the reasons for the control over the expenses at the military were not linked to the efficiency of an industry, more or less closed to the Army, but to an Army institution that needed to be considered as a whole, as the hospitals.

The Instruction for Military Hospitals of 1739 was not an amendment to previous regulations, in spite that it considered many issues that were regulated before (Corpas, 2005; Massons, 1994; Vega, 1988). In this sense, the size (186 pages) and structure (three Treatises and four specific regulations) of the Instruction show interesting features to consider the extent and the aims of the regulation. The aims of the Instruction for Military Hospitals could be remarked on two ideas: the control and recovery of the ill soldiers and the control over the resources of the Army.

The organisational chart of military hospitals reflects the previous aims. The control over the resources, and also the control over the ill soldiers, is explained by the role and place of the Controller. Being the third at the hierarchy, and the first inside the hospital, a main target of the regulation was the control (Corpas, 2005; Teijeiro, 2002). Remarkably, a governmental crisis (Funnell, 2009) – led by a need for resources at the Royal Treasury – supposed the emergence of an accounting post with a high authority at the hierarchy of a military institutions (Chwastiask, 2001). Such authority reached to the hiring or dismissal of employees (Puell, 2008; Riera, 1992). Being this one the top staff at the management of the military hospitals, the figure of the Controller is refereed through many of the articles of the Treatises of the Instruction for Military Hospitals of 1739. Thus, his authority on the hospital was unquestionable (Teijeiro, 2002). In this sense, it can be stated that accounting was a main solution of the expenses saving at the military hospitals.

Related to such ideas is the net of information flows that emerged from the Instruction for Military Hospitals. In this way, the Controller was the main receiver and sender of information about a hospital and, mostly, the only sender of information outside of military hospitals. The flows of information were concerned, mainly, on the days of stay of ill soldiers. Consequently, there were not soldiers that could come in or exit from a hospital without the approval of the Controller. Also, the control over the food and medicines were two main issues, controlled daily, as well as the census of ill people was updated each day. For the specific case of the campaign hospitals such control was enforced with reports from the Warehouse to the Controller on the stock received of beds, tools, equipment and goods. Also, the Room Commissioner sent, daily, the information on the ill soldiers to the Controller.

In the same way, the Controller had to report to the War Commissioners on the food that should be destroyed, the stock at the Warehouse and, monthly, a report on the ill people at the hospital, which was sent also to the Accounting Office for the payments. The information flows to outside of military hospitals, for the case of campaign hospitals, were also higher.

The net of information flows that emerged from the Instruction for Military Hospitals can be considered as complex, but once filtered by some restrictions, it appeared as reflexive of the aims of the management of military hospitals. Thus, it can be asserted that accounting was moulded to answer to the governmental crisis provoked by a financial crisis on the state resources (Funnell, 2009; see also Miller, 1994).

At the same way, considering the role of accounting and the Controller on the management of the hospital, the organisational chart and the standardisation of tasks over the medical activity and management of the stores towards the Controller, it can be concluded that accounting was a main target and the measure to organise the hospital. Accounting, at the military institution, was able to constitute the roles and tasks. Military hospitals became a problem of resource management open to the discipline of accounting (Funnell, 2009). Thus, “…accounting was densely interrelated with a particular way of delineating tasks and roles…” (Miller & O’Leary, 1987, p. 41). Accounting, therefore, provided a set of techniques and a language for the organisation of a hospital. Accounting, in this case, showed a constitutive role at the organisations (Miller, 1994).

For future research, it should be interesting to focus on the consequences of the implementation of the Instruction for Military Hospitals. The primary sources have allowed us to grasp that the impact of the Instruction for Military Hospitals was higher than expected. Thus, studies on the economic influence of the adoption of the Instruction (AGS, Guerra Moderna, Sup., box 2452), or the influence of accounting records on the inter-organizational relationships appear as two interesting areas for research (AGS, Guerra Moderna, Sup., box 681).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.