It is essential to understand the strategic importance of intensive care resources in the sustainable organisation of healthcare systems. Our objective has been to identify the intensive and intermediate care beds managed by Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Services (A-ICU and A-IMCU) in Spain, their human and technical resources, and the changes made to these resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and methodsProspective observational study performed between December 2020 and July 2021 to register the number and characteristics of A-ICU and A-IMCU beds in hospitals listed in the catalogue published by the Spanish Ministry of Health.

ResultsData were obtained from 313 hospitals (98% of all hospitals with more than 500 beds, 70% of all hospitals with more than 100 beds). One hundred and forty seven of these hospitals had an A-ICU with a total of 1702 beds. This capacity increased to 2107 (124%) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Three hundred and eight hospitals had an A-IMCU with a total of 3470 beds, 52.9% (2089) of which provided long-term care. The hospitals had 1900 ventilators, at a ratio of 1.07 respirators per A-ICU; 1559 anaesthesiologists dedicated more than 40% of their working time to intensive care. The nurse-to-bed ratio in A-ICUs was 2.8.

DiscussionA large proportion of fully-equipped ICU and IMCU beds in Spanish hospitals are managed by the anaesthesiology service. A-ICU and A-IMCUs have shown an extraordinary capacity to adapt their resources to meet the increased demand for intensive care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Los recursos de cuidados intensivos tienen valor estratégico y es necesario conocerlos para una planificación sanitaria sostenible. El objetivo es identificar las camas de cuidados intensivos e intermedios gestionadas por Servicios de Anestesiología y Reanimación (UCI-A y UCIM-A) en España, así como los recursos humanos y técnicos relacionados, y su variación durante la pandemia COVID-19.

Material y métodosEstudio nacional observacional prospectivo de diciembre de 2020 a julio de 2021. Se recogieron datos relativos al número y características de las camas de UCI-A y UCIM-A en hospitales del catálogo Nacional de Hospitales del Ministerio de Sanidad.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron datos de 313 hospitales (98% del total de más de 500 camas, 70% del total de más de 100 camas). En 147 de ellos se registraron UCI-A, con un total de 1.702 camas que se incrementaron hasta 2.107 (124%) durante la pandemia COVID-19. En 308 hospitales se registraron UCIM-A, con un total de 3.470 camas de las cuales el 52,9% (2.089) prestaban atención continuada. Se registraron 1.900 respiradores con un ratio de 1,07 respiradores por cama de UCI-A. 1559 anestesiólogos tenían una dedicación superior al 40% a los cuidados intensivos. El ratio de camas de UCI-A por cada profesional de enfermería fue de 2,8.

DiscusiónLos Servicios de Anestesiología gestionan un elevado número de camas UCI y UCIM en España, con una dotación adecuada de recursos. Han demostrado una gran capacidad de adaptación en situaciones de crisis dando respuesta al aumento de la demanda de cuidados intensivos durante la pandemia COVID-19.

References to specific care areas for critically ill hospitalised patients date back to the 19th century.1 However, the invasive mechanical ventilation unit created in 1952 in Copenhagen by the Danish anaesthesiologist Bjørn Ibsen during the polio epidemic is generally considered the origin of intensive care units (ICU) in Europe.2 Since then and up to the present day, ICUs have become an essential component of hospital care, constituting a link in the chain of care in an increasing number of processes, many of them surgical.3 Added to this is an increase in the expectations of healthcare professionals and users about the outcomes that intensive care can provide.4–6

Yet, there is little data on the actual availability of ICU beds in the national and international literature.7–10 In many European countries there are no official censuses, ICUs managed by different departments or services affiliated to the different Scientific Societies coexist, and most studies do not stratify data according to care level, including intermediate care units (IMCUs). It is therefore difficult to obtain reliable data and to interpret the published results. This lack of information prevents adequate planning, and any unexpected increase in demand for ICU beds can quickly overwhelm and exceed available resources, as occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Having the maximum information on available human and technical resources, as well as their adaptive capacity, enables contingency plans to be made with the capacity to multiply the number of available ICU beds, as was necessary in many regions during the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic.11–15

The primary objective of the present study is to identify the number of ICU and IMCU beds managed by anaesthesiology and resuscitation services (ICU-A, IMCU-A) in Spain and their associated human (medical and nursing) and material (number of ventilators) resources. The secondary objective is to describe the variations during the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and methodsNational, observational, descriptive, prospective study from December 2020 to July 2021.

We identified hospitals included in the Spanish National Catalogue of Hospitals of the Ministry of Health (CNHMS)16 that met the criteria for having an anaesthesiology and resuscitation department (ARD) according to the purpose and class of centre with which they were registered in 2020. The definitions of ICU-A and IMCU-A beds were established according to the level of care and in accordance with the standards and recommendations of the Ministry of Health,17 and the recommendations of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine,18 the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine,19 and the European Union of Medical Specialists 20:

ICU bed (care level II and III): effective bed, with the necessary material and human resources to provide continuous monitoring and organ support (24 h a day, every day of the year).

IMCU bed (care level I): bed with a dedicated monitoring system for patients at risk of deterioration of their condition but who do not require organ support, available continuously or non-continuously.

A form and user manual were designed for prospective online data collection, which included 68 variables relating to the identification of each hospital centre, as well as the number and characteristics of ICU-A and IMCU-A inpatient beds (Appendix A). Data were collected regarding structural resources present prior to February 2020 and their maximum variation in any of the waves of the COVID-19 pandemic recorded through July 2021. The activity of anaesthesiology physicians in ICUs or IMCUs managed by other hospital services was not recorded.

At least one researcher responsible for data collection in each hospital and in each autonomous community was selected from among professionals with proven experience linked to the regional anaesthesiology and resuscitation societies and to the Intensive Care Section of the Spanish Society of Anaesthesiology, Resuscitation, and Pain Therapy (SCI-SEDAR). Once the data collection process was completed, the hospital and regional investigators conducted a peer review, and a process of cleaning, homogenisation, purification, and subsequent structuring by the authors in charge of the statistical analysis. Hospitals with incomplete or inconsistent data were not included in the analysis.

The data were analysed using Microsoft® Excel 16® and IBM® SPSS 28®. Although the data were analysed for each participating hospital, to simplify publication, the values were grouped at the national and autonomous community levels, in the form of absolute values and/or proportions and expressing the distribution of the different means by the minimum and maximum values.

ResultsParticipation in the registry (Sample)A total of 575 CNHMS hospitals were identified that met the criteria for having an ARD, encompassing a total of 126,299 inpatient beds in 293 public, 280 private, and 2 Ministry of Defence facilities (Appendix B).

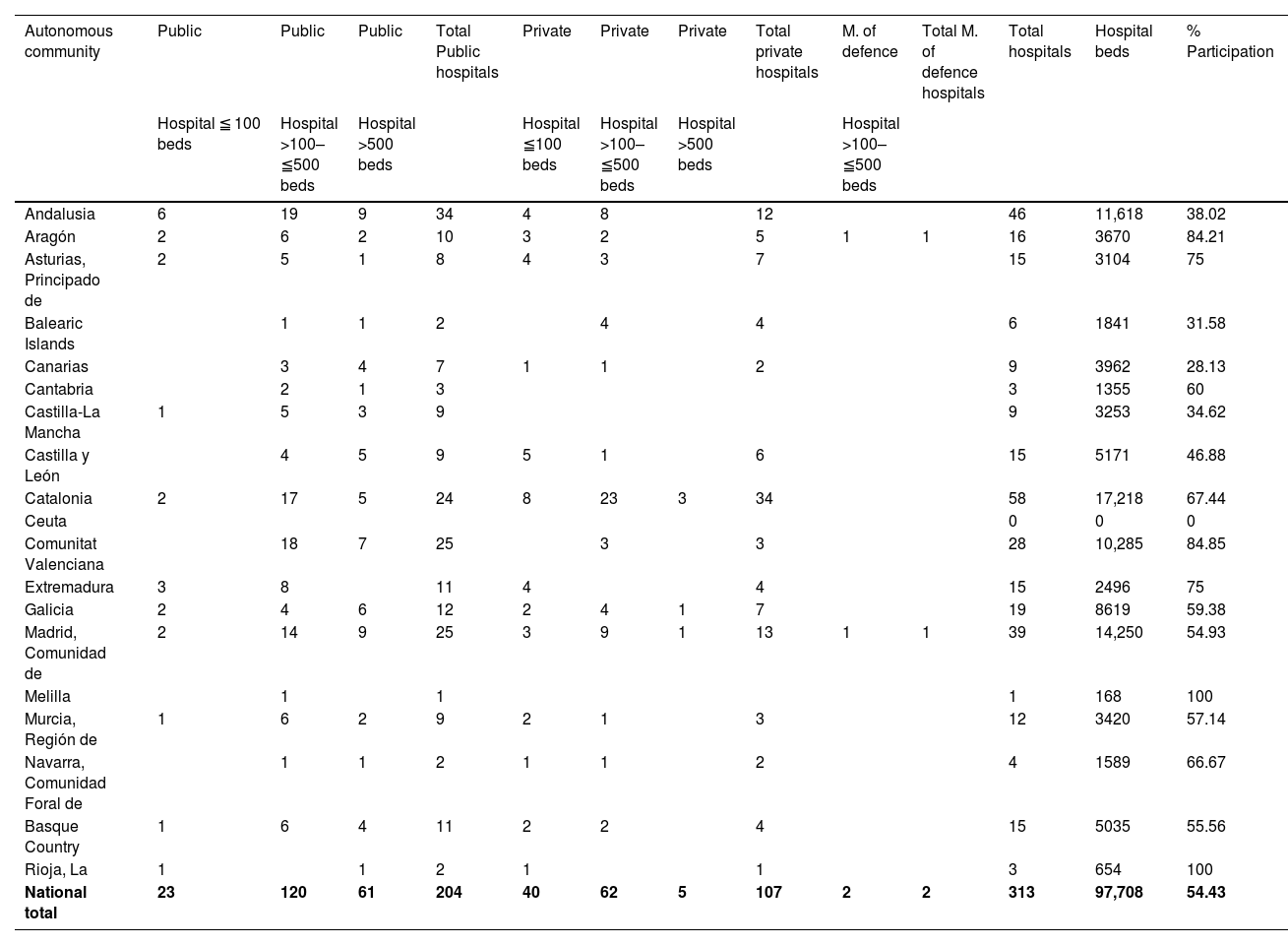

Valid data were obtained from 313 hospitals (54% of the total), 204 (65%) public centres, 107 (34%) private, and 2 from the Ministry of Defence, with a total of 97,708 hospital beds (77% of the total). This included 98% of hospitals with more than 500 beds, 70% with more than 100 beds, and 28% with fewer than 100 beds. Participation was heterogeneous among the different autonomous communities (Table 1) (Appendix B).

Hospitals included in the study and percentage of participation by autonomous community.

| Autonomous community | Public | Public | Public | Total Public hospitals | Private | Private | Private | Total private hospitals | M. of defence | Total M. of defence hospitals | Total hospitals | Hospital beds | % Participation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital ≦ 100 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital ≦100 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | |||||||

| Andalusia | 6 | 19 | 9 | 34 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 46 | 11,618 | 38.02 | |||

| Aragón | 2 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 3670 | 84.21 | |

| Asturias, Principado de | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 15 | 3104 | 75 | |||

| Balearic Islands | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 1841 | 31.58 | |||||

| Canarias | 3 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 3962 | 28.13 | ||||

| Cantabria | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1355 | 60 | |||||||

| Castilla-La Mancha | 1 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 3253 | 34.62 | ||||||

| Castilla y León | 4 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 15 | 5171 | 46.88 | ||||

| Catalonia | 2 | 17 | 5 | 24 | 8 | 23 | 3 | 34 | 58 | 17,218 | 67.44 | ||

| Ceuta | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Comunitat Valenciana | 18 | 7 | 25 | 3 | 3 | 28 | 10,285 | 84.85 | |||||

| Extremadura | 3 | 8 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 15 | 2496 | 75 | |||||

| Galicia | 2 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 19 | 8619 | 59.38 | ||

| Madrid, Comunidad de | 2 | 14 | 9 | 25 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 39 | 14,250 | 54.93 |

| Melilla | 1 | 1 | 1 | 168 | 100 | ||||||||

| Murcia, Región de | 1 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 3420 | 57.14 | |||

| Navarra, Comunidad Foral de | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1589 | 66.67 | ||||

| Basque Country | 1 | 6 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 15 | 5035 | 55.56 | |||

| Rioja, La | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 654 | 100 | |||||

| National total | 23 | 120 | 61 | 204 | 40 | 62 | 5 | 107 | 2 | 2 | 313 | 97,708 | 54.43 |

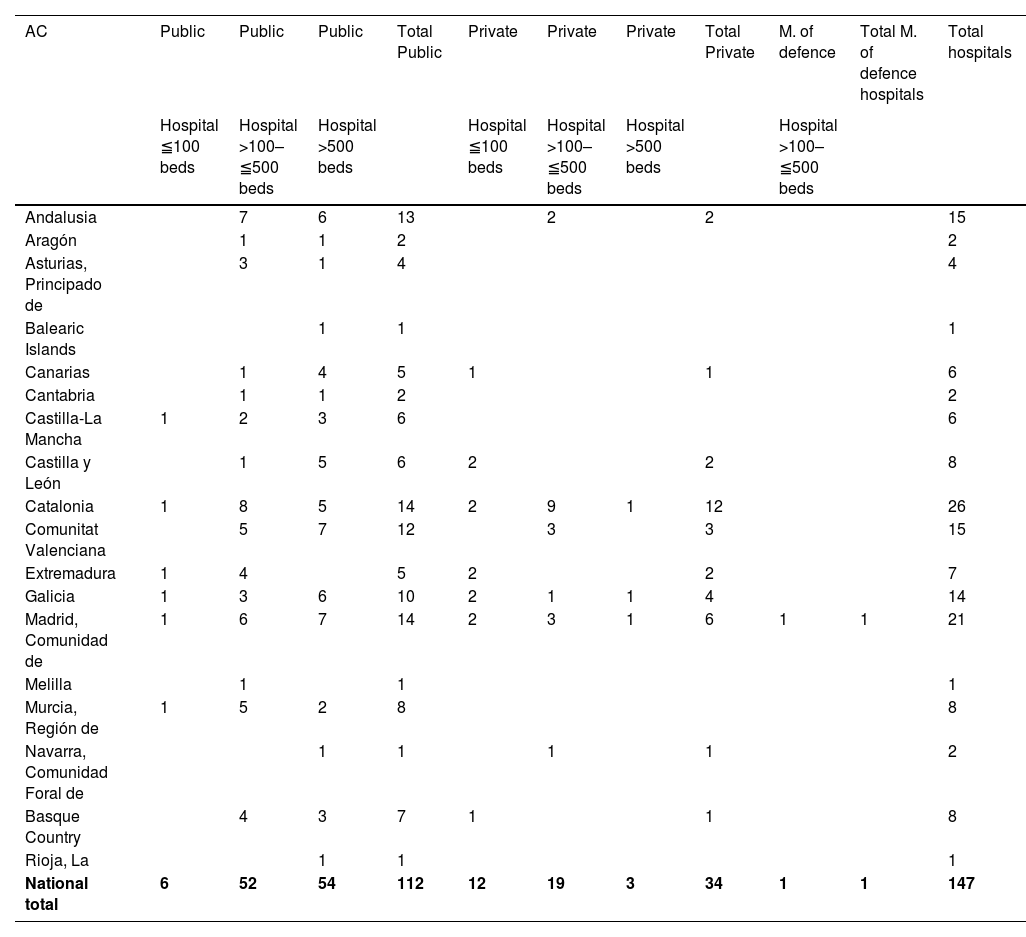

A total of 147 hospitals were recorded with an ICU-A, of which 112 (76%) were public (54 of them with more than 500 beds), 34 (23%) were private (3 with more than 500 beds), and 1 (0.7%) was a Ministry of Defence hospital with fewer than 500 beds (Table 2).

Hospitals with ICU-A included in the study.

| AC | Public | Public | Public | Total Public | Private | Private | Private | Total Private | M. of defence | Total M. of defence hospitals | Total hospitals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital ≦100 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital ≦100 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | |||||

| Andalusia | 7 | 6 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 15 | |||||

| Aragón | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Asturias, Principado de | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | |||||||

| Balearic Islands | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Canarias | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||||

| Cantabria | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Castilla-La Mancha | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 | ||||||

| Castilla y León | 1 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |||||

| Catalonia | 1 | 8 | 5 | 14 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 12 | 26 | ||

| Comunitat Valenciana | 5 | 7 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 15 | |||||

| Extremadura | 1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 7 | |||||

| Galicia | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 14 | ||

| Madrid, Comunidad de | 1 | 6 | 7 | 14 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 21 |

| Melilla | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Murcia, Región de | 1 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 8 | ||||||

| Navarra, Comunidad Foral de | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Basque Country | 4 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |||||

| Rioja, La | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| National total | 6 | 52 | 54 | 112 | 12 | 19 | 3 | 34 | 1 | 1 | 147 |

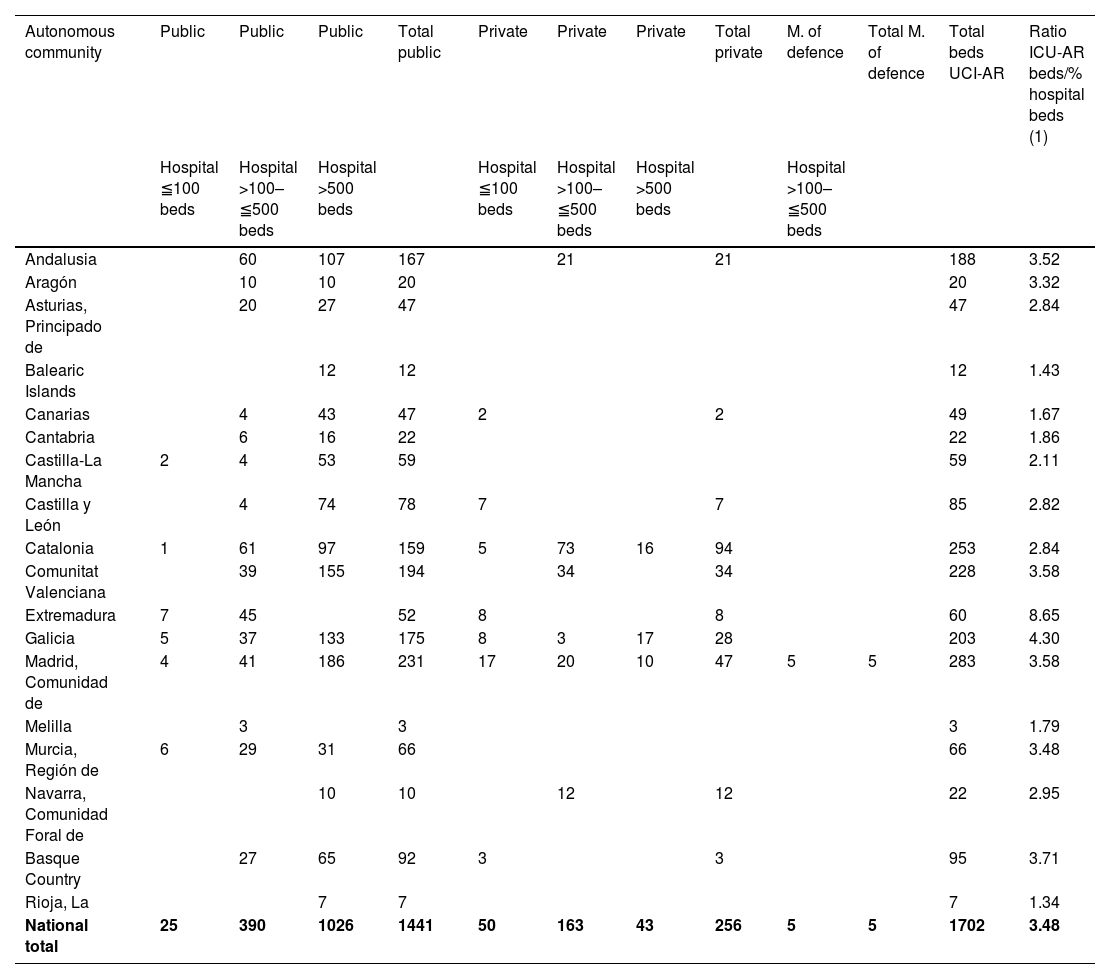

A total of 1702 ICU-A beds were recorded, of which 1441 (84.7%) were in public hospitals (1026 in hospitals with more than 500 beds), 256 (15%) in private hospitals (43 of them in hospitals with more than 500 beds), and 5 (0.3%) in the Ministry of Defence hospital (Table 3).

ICU-A beds included in the study.

| Autonomous community | Public | Public | Public | Total public | Private | Private | Private | Total private | M. of defence | Total M. of defence | Total beds UCI-AR | Ratio ICU-AR beds/% hospital beds (1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital ≦100 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital ≦100 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | ||||||

| Andalusia | 60 | 107 | 167 | 21 | 21 | 188 | 3.52 | |||||

| Aragón | 10 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 3.32 | |||||||

| Asturias, Principado de | 20 | 27 | 47 | 47 | 2.84 | |||||||

| Balearic Islands | 12 | 12 | 12 | 1.43 | ||||||||

| Canarias | 4 | 43 | 47 | 2 | 2 | 49 | 1.67 | |||||

| Cantabria | 6 | 16 | 22 | 22 | 1.86 | |||||||

| Castilla-La Mancha | 2 | 4 | 53 | 59 | 59 | 2.11 | ||||||

| Castilla y León | 4 | 74 | 78 | 7 | 7 | 85 | 2.82 | |||||

| Catalonia | 1 | 61 | 97 | 159 | 5 | 73 | 16 | 94 | 253 | 2.84 | ||

| Comunitat Valenciana | 39 | 155 | 194 | 34 | 34 | 228 | 3.58 | |||||

| Extremadura | 7 | 45 | 52 | 8 | 8 | 60 | 8.65 | |||||

| Galicia | 5 | 37 | 133 | 175 | 8 | 3 | 17 | 28 | 203 | 4.30 | ||

| Madrid, Comunidad de | 4 | 41 | 186 | 231 | 17 | 20 | 10 | 47 | 5 | 5 | 283 | 3.58 |

| Melilla | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1.79 | ||||||||

| Murcia, Región de | 6 | 29 | 31 | 66 | 66 | 3.48 | ||||||

| Navarra, Comunidad Foral de | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 22 | 2.95 | ||||||

| Basque Country | 27 | 65 | 92 | 3 | 3 | 95 | 3.71 | |||||

| Rioja, La | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1.34 | ||||||||

| National total | 25 | 390 | 1026 | 1441 | 50 | 163 | 43 | 256 | 5 | 5 | 1702 | 3.48 |

(1) Mean ratios of effective ICU-A beds per 100 hospital beds.

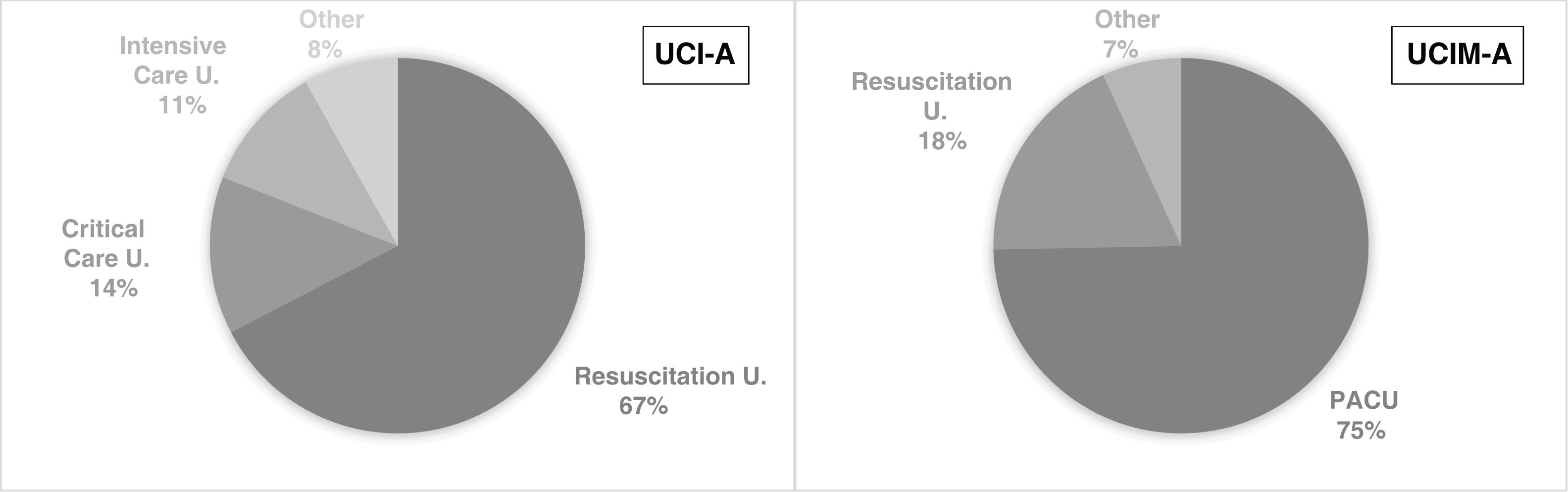

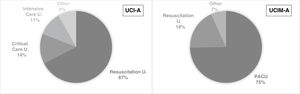

A total of 98 of the ICU-As were defined as surgical (66.7%), and 49 as multipurpose (33.3%). Of these, 99 (67.3%) were designated resuscitation units, 20 (13.6%) critical care units, and 16 (10.9%) intensive care units, the remaining 12 (8.2%) were recorded under another denomination (Fig. 1).

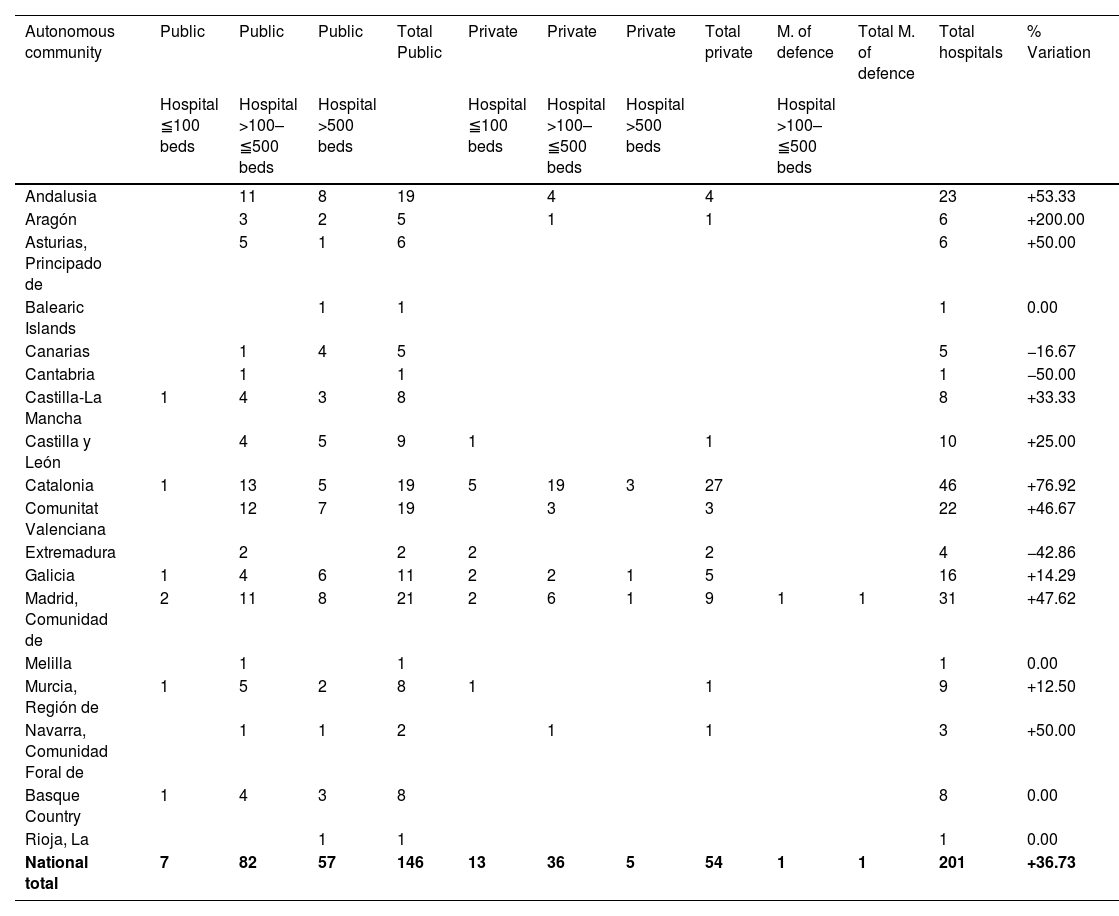

UCI-A during the COVID-19 pandemicA total of 201 hospitals with an ICU-A were recorded, of which 146 were public (72.6%, 57 with more than 500 beds), 54 private (26.9%, 5 with more than 500 beds), and 1 belonging to the Ministry of Defence (.5%). A total of 3809 ICU-A beds were recorded, of which 3265 were in public hospitals (2137 in hospitals with more than 500 beds), 534 in private hospitals (71 in hospitals with more than 500 beds), and 10 in the Ministry of Defence hospital (Table 4).

Hospitals with ICU-A during the COVID-19 pandemic included in the study.

| Autonomous community | Public | Public | Public | Total Public | Private | Private | Private | Total private | M. of defence | Total M. of defence | Total hospitals | % Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital ≦100 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital ≦100 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | ||||||

| Andalusia | 11 | 8 | 19 | 4 | 4 | 23 | +53.33 | |||||

| Aragón | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 6 | +200.00 | |||||

| Asturias, Principado de | 5 | 1 | 6 | 6 | +50.00 | |||||||

| Balearic Islands | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| Canarias | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | −16.67 | |||||||

| Cantabria | 1 | 1 | 1 | −50.00 | ||||||||

| Castilla-La Mancha | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 8 | +33.33 | ||||||

| Castilla y León | 4 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 10 | +25.00 | |||||

| Catalonia | 1 | 13 | 5 | 19 | 5 | 19 | 3 | 27 | 46 | +76.92 | ||

| Comunitat Valenciana | 12 | 7 | 19 | 3 | 3 | 22 | +46.67 | |||||

| Extremadura | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | −42.86 | ||||||

| Galicia | 1 | 4 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 16 | +14.29 | ||

| Madrid, Comunidad de | 2 | 11 | 8 | 21 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 31 | +47.62 |

| Melilla | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| Murcia, Región de | 1 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 9 | +12.50 | ||||

| Navarra, Comunidad Foral de | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | +50.00 | |||||

| Basque Country | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Rioja, La | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| National total | 7 | 82 | 57 | 146 | 13 | 36 | 5 | 54 | 1 | 1 | 201 | +36.73 |

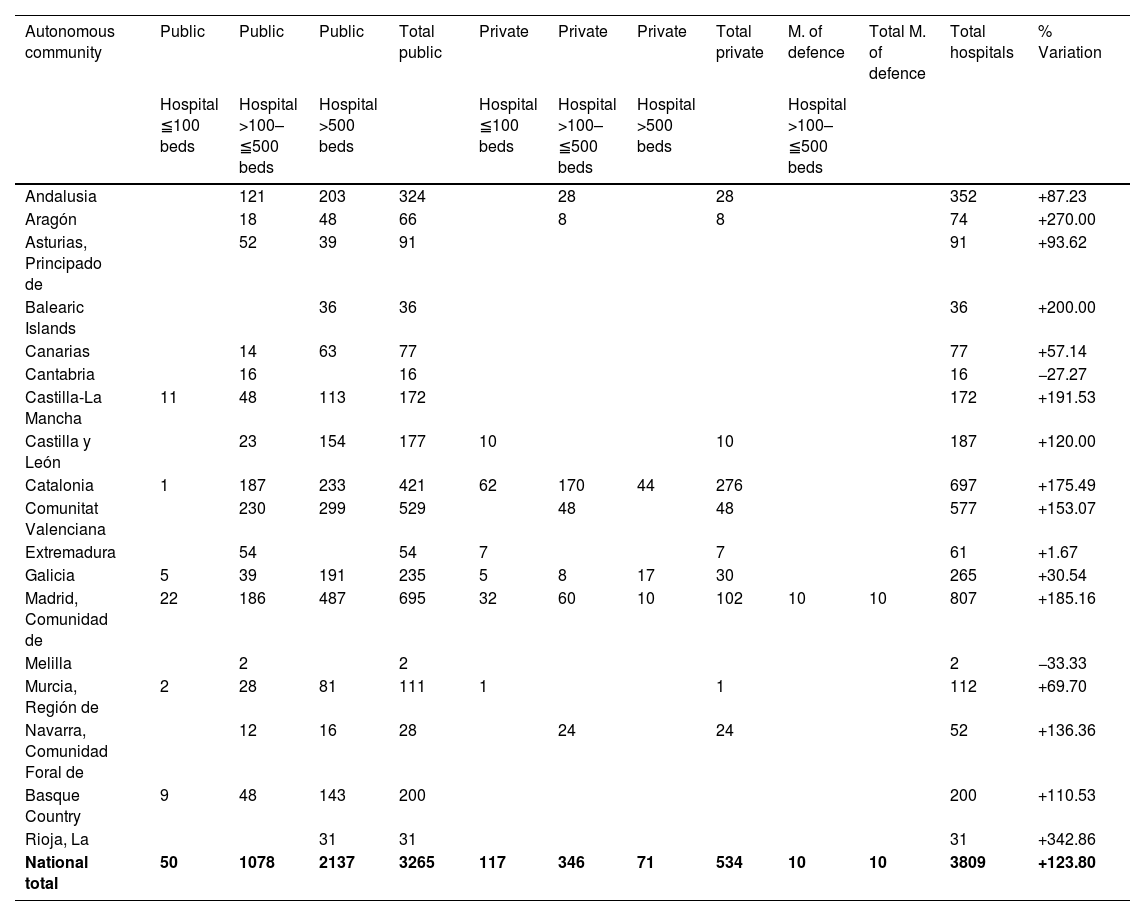

This represented an overall increase of 36% of the hospitals managing an ICU-A, with an increase of 30% in public hospitals (5% in hospitals with more than 500 beds), and 58% in private hospitals. The number of ICU-A beds increased by 2107 beds (124%), 126% in public hospitals (108% in those with more than 500 beds), 108% in private hospitals, and 100% in the Ministry of Defence hospital (Table 5).

ICU-A beds during the COVID-19 pandemic included in the study.

| Autonomous community | Public | Public | Public | Total public | Private | Private | Private | Total private | M. of defence | Total M. of defence | Total hospitals | % Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital ≦100 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital ≦100 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital >100–≦500 beds | ||||||

| Andalusia | 121 | 203 | 324 | 28 | 28 | 352 | +87.23 | |||||

| Aragón | 18 | 48 | 66 | 8 | 8 | 74 | +270.00 | |||||

| Asturias, Principado de | 52 | 39 | 91 | 91 | +93.62 | |||||||

| Balearic Islands | 36 | 36 | 36 | +200.00 | ||||||||

| Canarias | 14 | 63 | 77 | 77 | +57.14 | |||||||

| Cantabria | 16 | 16 | 16 | −27.27 | ||||||||

| Castilla-La Mancha | 11 | 48 | 113 | 172 | 172 | +191.53 | ||||||

| Castilla y León | 23 | 154 | 177 | 10 | 10 | 187 | +120.00 | |||||

| Catalonia | 1 | 187 | 233 | 421 | 62 | 170 | 44 | 276 | 697 | +175.49 | ||

| Comunitat Valenciana | 230 | 299 | 529 | 48 | 48 | 577 | +153.07 | |||||

| Extremadura | 54 | 54 | 7 | 7 | 61 | +1.67 | ||||||

| Galicia | 5 | 39 | 191 | 235 | 5 | 8 | 17 | 30 | 265 | +30.54 | ||

| Madrid, Comunidad de | 22 | 186 | 487 | 695 | 32 | 60 | 10 | 102 | 10 | 10 | 807 | +185.16 |

| Melilla | 2 | 2 | 2 | −33.33 | ||||||||

| Murcia, Región de | 2 | 28 | 81 | 111 | 1 | 1 | 112 | +69.70 | ||||

| Navarra, Comunidad Foral de | 12 | 16 | 28 | 24 | 24 | 52 | +136.36 | |||||

| Basque Country | 9 | 48 | 143 | 200 | 200 | +110.53 | ||||||

| Rioja, La | 31 | 31 | 31 | +342.86 | ||||||||

| National total | 50 | 1078 | 2137 | 3265 | 117 | 346 | 71 | 534 | 10 | 10 | 3809 | +123.80 |

The same descriptive and comparative analysis was performed (before and during the pandemic) (Appendix C).

There were 308 hospitals with IMCU-A (202 public, 104 private, 2 of the Ministry of Defence), with a total of 3470 IMCU-A beds. Of these, 60% (2089 beds) provided 24/7 continuous care.

A total of 230 (74.7%) of the IMCU-A were designated as post anaesthesia recovery units (PACU), 57 (18.5%) as resuscitation units, and the remaining 21 (6.8%) were recorded under other names (Fig. 1).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an overall decrease of 27% in the number of IMCU-A beds, with a relative increase of 3% in those providing continuous care.

Medical and nursing staffingThe 313 hospitals included in the study had 7774 doctors specialising in anaesthesiology and resuscitation. Of these, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 377 (4.9%) worked 100% of their working day in an ICU-A and 1182 (15.2%) at least 40% (Appendix D). No changes were recorded during the pandemic.

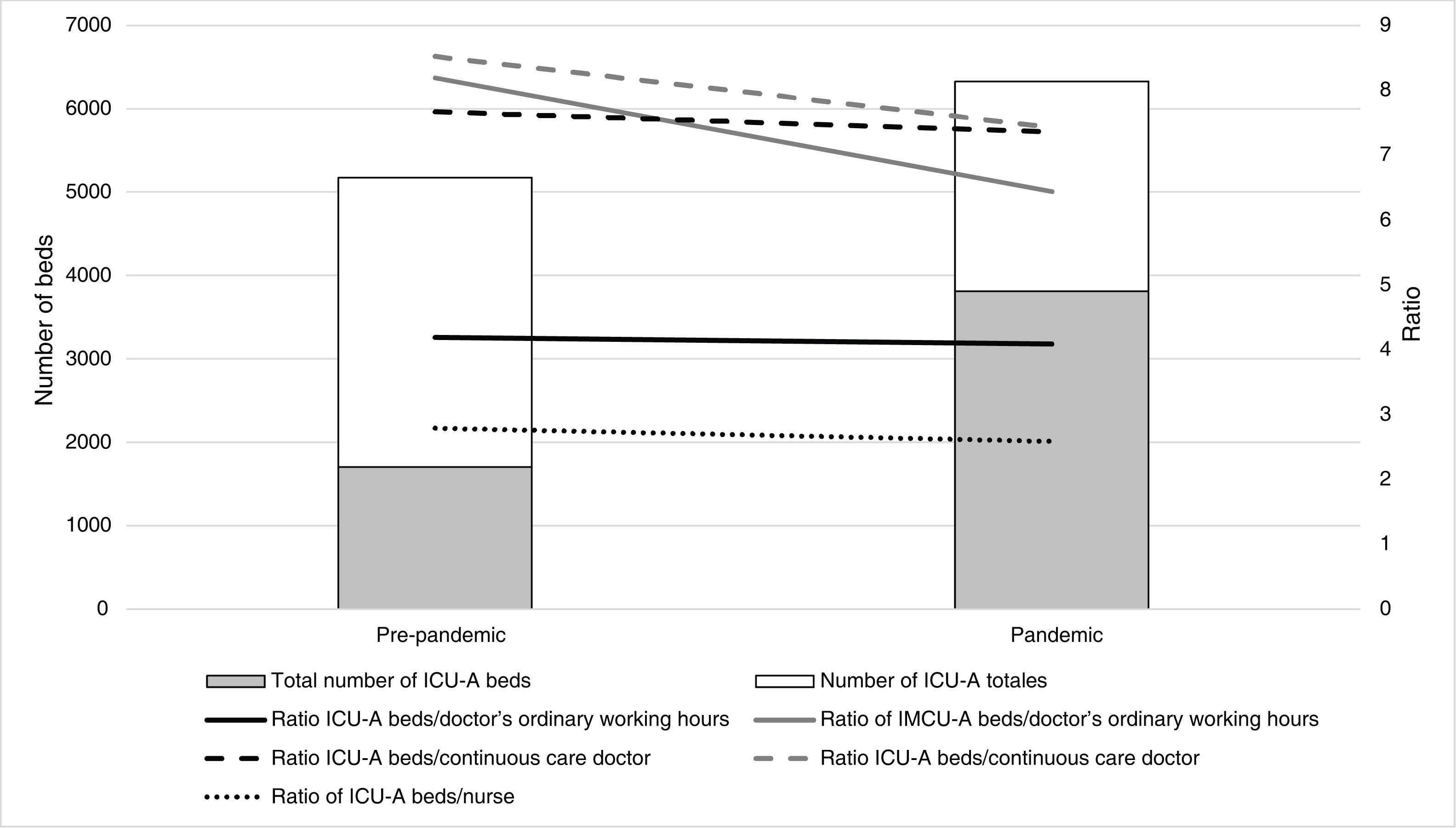

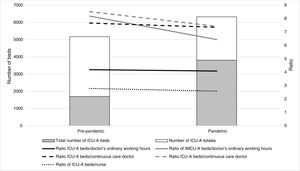

The national mean bed-to-doctor ratios during the regular working day were 4 (min. 3–max. 7) in ICU-A and 8 (3–10) in IMCU-A; and 8 (3–11) and 8 (3–17) respectively during hours of continuous care (Appendix E). During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a decrease in mean ratios of 2.4% in ICU-A and 21.4% in IMCU-A during regular working hours; and 4% and 12.8% respectively during continuous care hours.

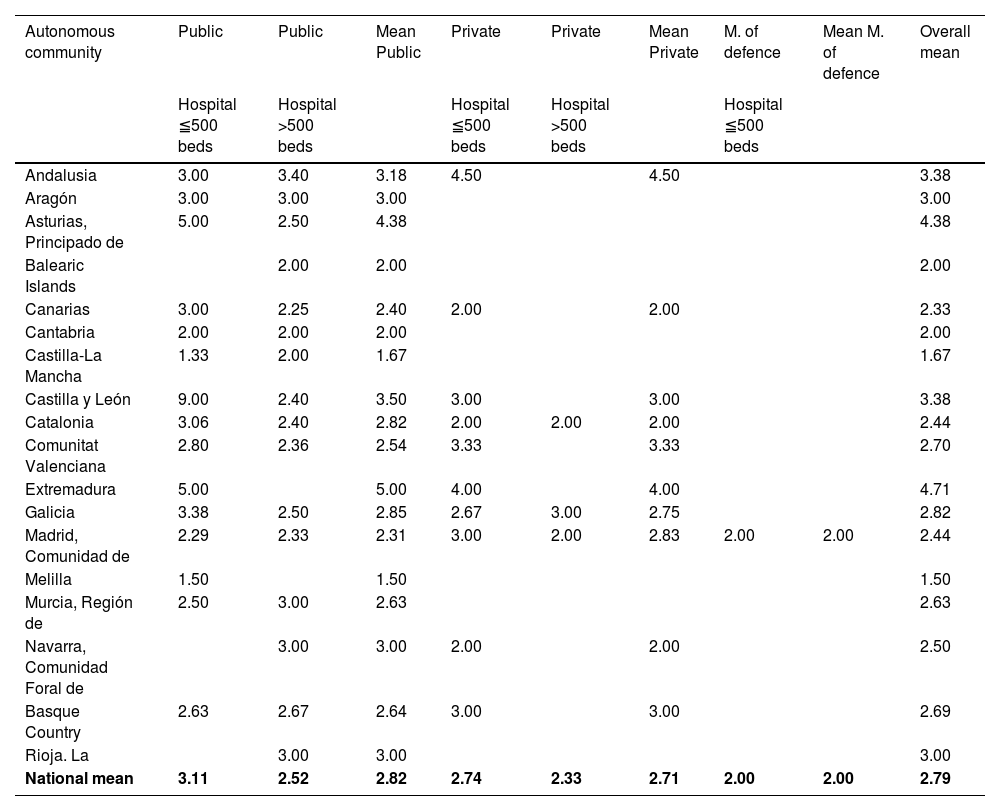

The national mean bed-to-nurse ratios were 3 (1–5) in ICU-A and 4 (3–6) in IMCU-A (Table 6 and Appendix F). During the pandemic, a reduction was recorded in the mean ratios of 7.3% in ICU-A and 18.7% in IMCU-A.

Ratio ICU-A beds per nurse.

| Autonomous community | Public | Public | Mean Public | Private | Private | Mean Private | M. of defence | Mean M. of defence | Overall mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital ≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital ≦500 beds | Hospital >500 beds | Hospital ≦500 beds | |||||

| Andalusia | 3.00 | 3.40 | 3.18 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 3.38 | |||

| Aragón | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | |||||

| Asturias, Principado de | 5.00 | 2.50 | 4.38 | 4.38 | |||||

| Balearic Islands | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | ||||||

| Canarias | 3.00 | 2.25 | 2.40 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.33 | |||

| Cantabria | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | |||||

| Castilla-La Mancha | 1.33 | 2.00 | 1.67 | 1.67 | |||||

| Castilla y León | 9.00 | 2.40 | 3.50 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.38 | |||

| Catalonia | 3.06 | 2.40 | 2.82 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.44 | ||

| Comunitat Valenciana | 2.80 | 2.36 | 2.54 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 2.70 | |||

| Extremadura | 5.00 | 5.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.71 | ||||

| Galicia | 3.38 | 2.50 | 2.85 | 2.67 | 3.00 | 2.75 | 2.82 | ||

| Madrid, Comunidad de | 2.29 | 2.33 | 2.31 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 2.83 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.44 |

| Melilla | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | ||||||

| Murcia, Región de | 2.50 | 3.00 | 2.63 | 2.63 | |||||

| Navarra, Comunidad Foral de | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.50 | ||||

| Basque Country | 2.63 | 2.67 | 2.64 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.69 | |||

| Rioja. La | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | ||||||

| National mean | 3.11 | 2.52 | 2.82 | 2.74 | 2.33 | 2.71 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.79 |

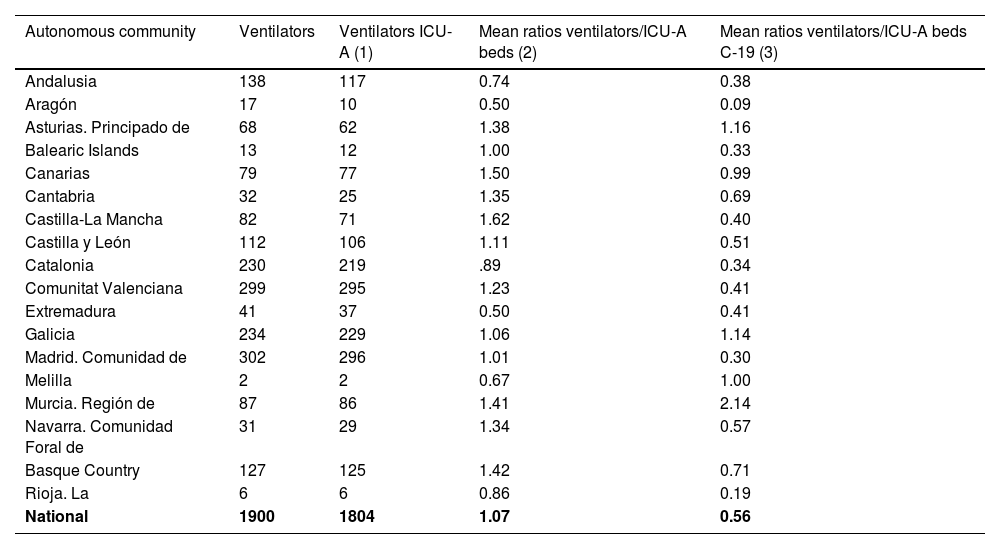

A total of 1900 intensive care ventilators managed by an ARD were recorded, 1804 in hospitals with an ICU-A. Mean ventilator to ICU-A bed ratios were 1.1 (0.5–1.6). During the pandemic, the mean ratios decreased by 47% [0.6 (0.1–2.1)] (Table 7). Non-intensive care-specific ventilators used in ICU-A during the pandemic were not recorded in this study.

Intensive care mechanical ventilators included in the study.

| Autonomous community | Ventilators | Ventilators ICU-A (1) | Mean ratios ventilators/ICU-A beds (2) | Mean ratios ventilators/ICU-A beds C-19 (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 138 | 117 | 0.74 | 0.38 |

| Aragón | 17 | 10 | 0.50 | 0.09 |

| Asturias. Principado de | 68 | 62 | 1.38 | 1.16 |

| Balearic Islands | 13 | 12 | 1.00 | 0.33 |

| Canarias | 79 | 77 | 1.50 | 0.99 |

| Cantabria | 32 | 25 | 1.35 | 0.69 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 82 | 71 | 1.62 | 0.40 |

| Castilla y León | 112 | 106 | 1.11 | 0.51 |

| Catalonia | 230 | 219 | .89 | 0.34 |

| Comunitat Valenciana | 299 | 295 | 1.23 | 0.41 |

| Extremadura | 41 | 37 | 0.50 | 0.41 |

| Galicia | 234 | 229 | 1.06 | 1.14 |

| Madrid. Comunidad de | 302 | 296 | 1.01 | 0.30 |

| Melilla | 2 | 2 | 0.67 | 1.00 |

| Murcia. Región de | 87 | 86 | 1.41 | 2.14 |

| Navarra. Comunidad Foral de | 31 | 29 | 1.34 | 0.57 |

| Basque Country | 127 | 125 | 1.42 | 0.71 |

| Rioja. La | 6 | 6 | 0.86 | 0.19 |

| National | 1900 | 1804 | 1.07 | 0.56 |

(1) Intensive care mechanical ventilators in hospitals with an ICU-A. (2) Mean ratios of mechanical ventilators to ICU-A beds. (3) Mean ratios of mechanical ventilators to ICU-A beds during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although this study cannot be considered an exhaustive national catalogue of intensive and intermediate care resources managed by an ARD, it does include a high proportion of those available in our country. We consider the study sample to be representative of hospitals with more than 100 beds, as well as those under public management.

Given that the data was collected using a form, and despite the fact that the variables were defined in a user manual, unintentional bias on the part of the recorders cannot be ruled out.

ICU-A bedsThis study presents the first national registry of ICU-A beds. Previous publications offer us, from different perspectives, data on these units, although they are not comparable with each other for different reasons. A study published in Europe in 2012 recorded a provision of 11.5 ICU beds per 100,000 inhabitants, with approximately 2.8 ICU beds per 100 acute inpatient beds, with marked differences between different countries.9 A study published in Spain in 2013 recorded 5569 intensive care beds, of which 3336 were managed by intensive care services (ICS) and 2233 by other medical services, mostly surgical ICUs managed by an ARD.10 A previous study published in Spain in 2010 had identified 3498 ICU beds in teaching hospitals, 2043 managed by ICS, and 1455 by an ARD, and 1572 additional surgical intermediate care beds managed by an ARD.7 In the present register, a greater number of ICU-A beds were identified (1702), which could be explained by the growth that these units have experienced in the last 10 years and by possible selection biases of the hospitals surveyed in previous studies.

According to the data of the present study, most of the ICU-A beds (60%) belong to public hospitals with more than 500 beds and to surgical (66%), or multipurpose (33%) units, which means we can infer that a differentiating element of the ICU-A with respect to units managed by other services is that they provide care preferentially to surgical patients. In contrast, in a study published in 2015 on 138,999 patients admitted to Spanish ICUs, primarily multipurpose, the reason for admission was surgical in only 32% of cases.21 The ratio of 1.7 ICU-A beds per 100 inpatient beds at national level is below the mean value of 2.8 published in Europe,9 which puts into context the ratio of ICU-A beds to total ICU beds in Spain, estimated at between 3.6 and 5.5, according to different authors.9,10 However, in hospitals that have an ICU-A, the mean ratio of ICU-A beds per 100 inpatient beds reached a value of 3.4%, with a mean value per community of min. 1.3% and max. 8.6%. Therefore, we can state that, although not all hospitals have an ICU-A, and there is great geographic variability, those that do have an ICU-A have a considerable number of beds.

UCI-A beds during the COVID-19 pandemicDuring the early phases of the pandemic in Europe, increases in ICU bed capacity were recorded ranging from 15% in Denmark to 226% in Ireland, with values close to 100% in most of the countries for which data are available.12 The contingency plans implemented by ARDs during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain made it possible to increase the number of hospitals with ICU-A by 36% and the number of beds by 124% (up to 2107), thus ensuring COVID and non-COVID critical patient care that would otherwise not have been possible. Added to this is the collaboration and support of numerous anaesthesiologists in units managed by intensive care and pneumology services, sometimes the majority in these units, which has not been included in this study.

However, the true success of this strategy should not only be evaluated based on the high number of ICU resources managed, but also on the excellent morbimortality results published by the Spanish ICU-A network.22–26

Much of the increase in ICU-A beds came from the reallocation of ICU-A beds, and the adaptation of operating theatres and other hospital areas. This demonstrates the enormous adaptive capacity that characterizes ARDs, based on their ability to reallocate quickly and efficiently human and material resources from surgical areas or intermediate care units in response to unexpected demand for intensive care. This capacity had already been documented in our recent history, and was what made it possible to provide adequate care to many of the victims of the attacks of March 11, 2004 in Madrid.27

IMCU-A bedsIMCU-A beds have fewer human and material resources, and therefore generate lower costs.28 As in the case of ICUs, there are both multipurpose IMCUs and specific IMCUs for certain processes or pathologies. The IMCU-As in the present study are mainly dedicated to providing post-anaesthesia, post-operative, or post-intervention care. Although there is no universal definition of IMCU, standards for post-anaesthesia care units (PACU) have been established in Europe.20 The Ministry of Health Surgical Block Standards and Recommendations recommend 1.5–2 post-anaesthesia care beds per operating theatre.29

ICU beds have been inconsistently included in previous studies on intensive care resources.7,9,10,30 The present study identified 3470 IMCU-A beds, of which 2089 (60%) provide continuous care, making them de facto level I ICU beds if they have the capacity to provide respiratory support.17–19 The SEDAR White Paper attempted to provide an approach to the organisation of this type of unit,31 but despite their importance in the healthcare system and the fact that they provide care to tens of thousands of patients annually, there is no other document in our country that defines the standards for this type of unit, sometimes of similar or greater complexity than others acknowledged in official documents.

IMCU-A during the COVID-19 pandemicThe number of IMCU-A beds decreased by 27% (−952 beds), with a relative increase (3%) in those providing continuous care. These data, which were associated with the increase in IMCU-A beds, show how contingency plans to increase ICU beds during the pandemic were made possible in large part through the reallocation of resources managed by an ARD usually dedicated to surgical processes.11,14,15 Similarly, it shows that many of the IMCU-As have the resources and flexibility to convert to level II or III ICUs when the situation requires it.

Medical staffing in ICU-AThe European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) recognises that there is a multidisciplinary intensive care model in Europe, which can be accessed through both primary specialty programmes in intensive care medicine and other core specialties that include intensive care medicine competencies in their training programmes over a two-year period,32 anaesthesiology being the most widespread example. The Union of European Medical Specialists together with the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care (ESAIC) have recently updated their anaesthesiology training programme,33 emphasising intensive care as a core competency of the specialty. In order to meet these European training standards, the Spanish National Specialties Commission has formally requested a new 5-year training programme for the specialty of anaesthesiology.34

The present study demonstrates that this model is a reality in Spain, where 1 in 5 anaesthesiologists perform at least 40% of their activity in an ICU.

There are no standards or recommendations on the ratio of ICU beds to medical staff, and the evidence on the influence of this factor on outcomes is difficult to interpret. 35 However, as the present study demonstrates, there being 7774 active anaesthesiology and resuscitation physicians shows an enormous potential of human resources that could be reassigned from surgical areas to ICU-A during the pandemic; when despite the increase in the number of beds (124%), the ratio of beds per doctor decreased, both during the regular working day and during continuous care (Fig. 2).

These data reinforce the notion that it is essential that anaesthesiologists have training strategies that ensure the acquisition and maintenance of competencies in intensive care medicine throughout their professional career.

Nurse staffing in ICU-ANurse staffing has been used to determine the level of care in ICUs.18,19 A recent study published by intensive care nurses in Spain recorded a ratio of 2–3 ICU beds per nurse in 69% of the participating units, with variable ratios in 27% of the units.36 In the present study, an average of 2.7 ICU-A beds per nurse was recorded, demonstrating that nurse staffing does not differ in general terms between ICU-As and ICUs managed by other specialties in Spain. During the pandemic, despite the increase (124%) in the number of ICU-A beds, the ratio of beds per nurse improved, which has been noted by other authors.37 This data can be interpreted as an indicator of the success of contingency plans and the ability of ARDs to quickly and efficiently reallocate human resources from surgical areas or intermediate care units in response to an unexpected demand for intensive care (Fig. 2).

Provision of intensive care respiratorsThe ability to provide invasive mechanical ventilation is one of the requirements for defining an ICU bed.19 The recent pandemic has demonstrated that intensive care ventilators are a resource of great strategic value. In the present study, the number of ventilators exceeded the number of ICU-A beds, which can be considered an indicator of their adequate provision. However, the fact that the number of ICU-A beds increased 2.24-fold, together with the fact that the most frequent cause of admission was respiratory failure, led to an increase in the demand for ventilators that the market was unable to supply in the early phases of the pandemic. A large number of new ICU-A beds were equipped with other types of ventilators, mostly anaesthesia machines and transport ventilators or other ventilators not specific to intensive care. Although these types of ventilators have been shown to have suboptimal characteristics for the treatment of the most severe cases of respiratory distress,38,39 the survival results published by the Spanish ICU-A network in the COVID-19 pandemic were excellent.22–26

Overall viewIt has recently been published that 70% of intensive care resources in Europe are managed by an ARD, reaching 100% in Scandinavian countries.40 The data of the present study demonstrate that Spanish ARDs manage numerous intensive care resources, ranging from IMCU or level I ICU, to ICU of the highest complexity. Royal Decree 69/2015, of February 6, regulating the Registry of Specialised Health Care Activity,41 recognises specific intensive care units, coronary units, large burn units, neonatal and paediatric intensive care units as ICUs as well as post-operative resuscitation units with a fixed number of beds and where administrative admissions take place. However, the term “resuscitation unit” used to identify the majority of ICU-As (67.34% in this study) has proven a non-specific term, as it is used interchangeably to identify IMCU-As in 18.5% of cases. The replacement of the term “resuscitation unit” with the term “anaesthesia intensive care unit” has been previously proposed by some authors.42

A strategic lesson learned from the pandemic is that multidisciplinary and coordinated models of intensive care are more efficient models that can provide sustainability from a human resource management perspective, and the versatility and flexibility needed to adapt ICUs to a changing demand for care.11–15 The results of this study show the inherent adaptive capacity of the ICU-A and IMCU-A, which made it possible to cope with an exceptional increase in the demand for intensive care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study highlights the need for the vision of anaesthesiology in the management of intensive care at regional and national level, the need to improve the administrative organisation of the IMCU-A, and the rationality of the fifth year of the specialty in our country.

ConclusionsThe present study shows that the ARDs manage a high number of the ICU and IMCU beds available in Spain, and that they have an adequate amount of medical and nursing staff, as well as numerous essential strategic resources, such as intensive care ventilators. The ARDs have demonstrated a great capacity for readapting and reallocating resources to respond to changing needs in crisis situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic, with good results. However, given the constant variation over time of ICU and IMCU resources, and their strategic value, an official registry of ICUs and IMCUs in the different autonomous communities is advisable, which in turn would converge in a national and European census.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.