In December 2019, the Wuhan Municipal Health and health Commission (Hubei Province, China) reported a series of cases of pneumonia of unknown aetiology. On January 7, 2020, the Chinese authorities identified as a causative agent of the outbreak a new type of virus of the Coronaviridiae family, called SARS-CoV-2. Since then, thounsands of cases have been reported with global dissemination. Infections in humans cause a broad clinical spectrum ranging from mild upper respiratory tract infection, to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and sepsis. There is not specific treatment for SARS-CoV-2, which is why the fundamental aspects are to establish adequate prevention measures and support treatment and management of complications.

En diciembre del 2019, la Comisión Municipal de Salud y Sanidad de Wuhan (provincia de Hubei, China) informó de una serie de casos de neumonía de etiología desconocida. El 7 de enero del 2020, las autoridades chinas identificaron como agente causante del brote un nuevo tipo de virus de la familia Coronaviridae, denominado SARS-CoV-2. Desde entonces, se han notificado miles de casos con una diseminación global. Las infecciones en humanos provocan un amplio espectro clínico que va desde infección leve del tracto respiratorio superior, hasta síndrome de distrés respiratorio agudo grave y sepsis. No existe un tratamiento específico para SARS-CoV-2, motivo por lo que los aspectos fundamentales son establecer medidas adecuadas de prevención y el tratamiento de soporte y manejo de las complicaciones.

In December 2019, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission (Hubei Province, China) reported a series of cases of pneumonia of unknown aetiology, all with a history of exposure to a wholesale seafood, fish and live animal market in Wuhan.1 On 7 January 2020, Chinese authorities identified a new type of virus from the Coronaviridae family called SARS-CoV-2 as the causative agent. Since then, thousands of cases have been reported worldwide. As of 11 March 2020, more than 118,000 cases of COVID-19 (the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2) have been documented in 114 countries, with more than 4200 deaths, of which approximately 95% of cases and 97% of deaths have occurred in China. Community transmission is now believed to exist in mainland China, Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Iran and Italy (Lombardy, Veneto, Emilia-Romagna and Piedmont regions). In Spain, more than 2000 cases have been confirmed so far, some of them with no epidemiological criteria.

Coronaviruses belong to the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae of the Coronaviridae family, and 7 coronaviruses that affect humans have so far been described (HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2). SARS CoV-2 appears to have been introduced into humans through an as yet undetermined animal reservoir, and has since spread from person to person. The vast majority of these viruses cause mild upper respiratory tract infections in immunocompetent adults, and can cause more severe symptoms in patients with risk factors.

On 30 January 2020, the Director-General of the World Health Organisation declared the outbreak of the new 2019 coronavirus in the People's Republic of China a public health emergency of international concern.

EpidemiologyThe largest case series published so far by the Chinese centre for disease control includes a total of 44,672 confirmed cases as of February 11.2 Of these, 87% were between 30 and 79 years old, 2% were under 20 years old, and 3% were over 80 years old; 81% of cases were reported as mild, while 14% were severe and 5% critical, with a total of 1023 deaths (case fatality rate 2.3%). The mortality rate was higher in patients with comorbidities: cardiovascular disease (10.5%), diabetes (7.3%), chronic respiratory disease (6.3%), high blood pressure (6%), oncological disease (5.6%). A quarter (26%) of patients requiring hospitalisation were admitted to the ICU, of which 47% required mechanical ventilation and 11% required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). The mortality rate was far higher among critically ill patients.2,3 Confirmed cases included 1716 healthcare workers, of which 14.8% were in serious or critical condition, and 5 died.

Infections in humans cause a broad clinical spectrum ranging from mild upper respiratory tract infection to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and sepsis. Four case series of hospitalized patients have been published in Wuhan, China, with 5, 41, 99 and 138 cases, respectively.4–8 The most frequent symptoms in hospitalised patients were fever, shortness of breath, and dry cough. Digestive symptoms (diarrhoea and nausea) were less common. Common lab findings include: lymphopaenia, prolonged prothrombin time, increased lactate dehydrogenase and CRP. The most common radiological findings were bilateral pulmonary infiltrates.

Based on studies published in Wuhan, China, the 28-day mortality rate of critically ill ICU patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia was estimated at 61.5%.3

The average incubation period was between 5.2 and 12.5 days,4 although cases with incubation periods of 24 days have been documented.

Based on current evidence, person to person transmission5 mainly occurs via respiratory droplets (up to 2m) and by mucosal contact with contaminated material (oral, ocular and nasal). It can also be transmitted by aerosols during aerosol-generating therapeutic procedures. Faecal-oral transmission is another hypothesis for which there is no evidence to date. The virus has been detected in stool samples in some infected patients, but the significance of this with regard to transmission is uncertain. One case of disease transmission by an asymptomatic carrier has so far been documented.9 The average number of secondary cases produced from one infected individual has been estimated at between 2 and 3.

DiagnosisDiagnostic tests are currently performed in all patients who meet any of the following criteria:

- 1.

Clinical picture compatible with acute respiratory infection of any severity and any of the following exposures in the 14 days prior to onset of symptoms:

- a.

History of travel to areas with evidence of community transmission.

- b.

History of close contact with a probable or confirmed case.

- a.

- 2.

Severe acute respiratory infection (fever and at least one sign or symptom of respiratory illness [cough, fever, or tachypnoea]) requiring hospitalisation after ruling out other possible infectious aetiologies that may justify the clinical picture.

Diagnostic confirmation of coronavirus is performed using molecular techniques (RT-PCR) and by comparing genomic sequencing with SARS-CoV-2.

The recommended samples are:

- 1.

Respiratory tract:

- a.

Upper, nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal exudate in patients with mild disease.

- b.

Lower, preferably bronchoalveolar lavage, sputum and/or tracheal aspirate, particularly in patients with severe respiratory disease.

- a.

If initial tests are negative in a patient with high clinical and epidemiological suspicion of SARS-CoV-2 (particularly when only upper respiratory tract samples have been collected), diagnostic testing should be repeated with new respiratory tract samples.

Once cases have been confirmed, the following samples should also be sent for testing:

- 1.

Blood: blood tests are useful for confirming the immune response to coronavirus infection. In this case, the first sample should be collected in the first week of illness (acute phase) and the second sample 14–30 days later.

- 2.

Faeces and urine: to confirm or rule out virus excretion via alternative routes.

There is no specific treatment for SARS-CoV-2; instead, treatment is based on supportive care and management of complications.10–12

- 1.

Early start of supportive care in patients with respiratory involvement (tachypnoea, hypoxaemia) or shock.

- 2.

Advanced respiratory support. Some patients can develop severe respiratory failure, which will usually appear around the eighth day after the onset of symptoms.

High flow nasal oxygen or non-invasive mechanical ventilation, being aerosol-generating procedures, should be reserved for very specific patients who must be closely monitored; intubation should never be delayed unnecessarily. Patients who require invasive mechanical ventilation should receive lung protection ventilation in accordance with current clinical guidelines. Patients with severe ARDS may need to be ventilated in the prone position, with neuromuscular blockade during the first 24h and elevated PEEP. If ventilatory difficulties persist despite these measures, the use of ECMO is recommended, since this can improve survival, according to the scant information available.13,14

Patient-ventilator disconnection should be minimised by using closed-loop systems, and active humidification must be avoided by using heat and moisture exchangers.

- 3.

Management of septic shock. Generally speaking, the recommendations of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign are applicable to the management of septic shock in patients with SARS-CoV-2.

- 4.

Antimicrobial treatment. Administration of antimicrobials should be avoided unless there is suspicion of associated sepsis or bacterial superinfection. In this case, empirical antibiotic treatment for community-acquired pneumonia should be started early in accordance with clinical guidelines and the patient's specific characteristics.

In patients with ARDS, superinfection is frequently associated with septic shock and multi-organ failure. Superinfection with pathogens such as Acinetobacter baumanii and Apergillus fumigatus have been described.

- 5.

Systemic steroid treatment. Systemic steroids should not be routinely administered to treat ARDS or viral pneumonia, unless indicated for another reason.15 A systematic review of observational studies in which corticosteroids were used in patients with SARS found no significant survival benefit, while their use was associated with adverse effects such as an increased incidence of infection and delayed viral clearance.

- 6.

Treatment with specific antiviral agents. There is no conclusive evidence that antivirals are effective in patients with SARS-CoV-2. Results are still pending from several ongoing clinical trials:

- –

Neuraminidase inhibitors: there are no data available on their effectiveness in the treatment of SARS CoV-2, so routine use is not recommended unless there is a risk of concomitant infection with influenza viruses.

- –

Nucleoside analogues: remdesivir is believed to have potential as a treatment for SARS CoV-2. In clinical trials in animals infected with MERS-CoV, both viraemia and lung damage were significantly reduced compared to controls A randomised controlled clinical trial is currently underway to evaluate its efficacy and safety in these patients.

- –

Protease inhibitors: inhaled interferon-α (broad antiviral spectrum) and the combination of lopinavir/ritonavir (in vitro activity against SARS CoV-2) are currently being administered as antiviral therapy, but there is still no evidence that these are clinically effective.

- –

Monoclonal antibodies: these could be useful in SARS CoV-2 infection based on their good results in patients with Ebola (REGN-EB3, MAb114).

- –

Off-label use of these drugs is only permitted in ethically approved clinical trials or in the context of monitored emergency use of unregistered and investigational interventions.

Practical recommendations in the workplaceThe patient should preferably be placed in a negative pressure isolation room that meets established standards (12 air changes/hour, HEPA filter and airlock). The number of people caring for the patient and the time spent in the room must be reduced to the absolute minimum.16 Every effort should be made to avoid intra-hospital transfers by performing all exploratory studies at the beside using portable equipment. If unavoidable, patient must wear a face mask during transfer (Table 1).

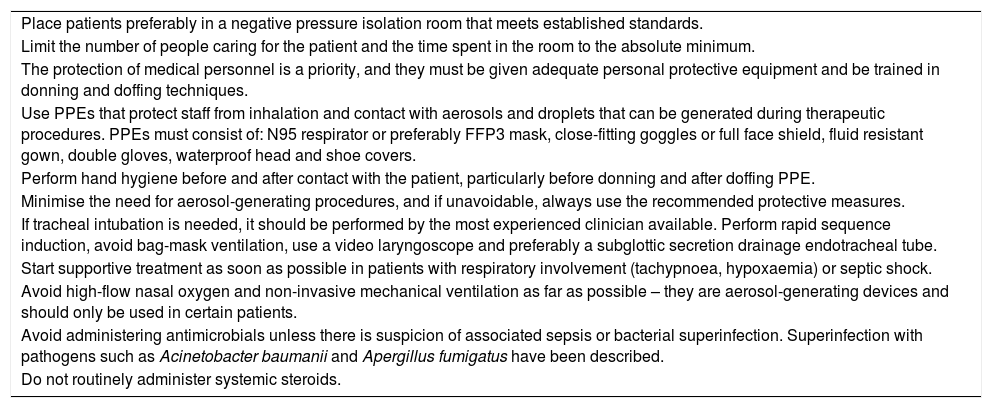

Recommendations for the management of patients with suspected or confirmed coronavirus infection (SARS-CoV-2).

| Place patients preferably in a negative pressure isolation room that meets established standards. |

| Limit the number of people caring for the patient and the time spent in the room to the absolute minimum. |

| The protection of medical personnel is a priority, and they must be given adequate personal protective equipment and be trained in donning and doffing techniques. |

| Use PPEs that protect staff from inhalation and contact with aerosols and droplets that can be generated during therapeutic procedures. PPEs must consist of: N95 respirator or preferably FFP3 mask, close-fitting goggles or full face shield, fluid resistant gown, double gloves, waterproof head and shoe covers. |

| Perform hand hygiene before and after contact with the patient, particularly before donning and after doffing PPE. |

| Minimise the need for aerosol-generating procedures, and if unavoidable, always use the recommended protective measures. |

| If tracheal intubation is needed, it should be performed by the most experienced clinician available. Perform rapid sequence induction, avoid bag-mask ventilation, use a video laryngoscope and preferably a subglottic secretion drainage endotracheal tube. |

| Start supportive treatment as soon as possible in patients with respiratory involvement (tachypnoea, hypoxaemia) or septic shock. |

| Avoid high-flow nasal oxygen and non-invasive mechanical ventilation as far as possible – they are aerosol-generating devices and should only be used in certain patients. |

| Avoid administering antimicrobials unless there is suspicion of associated sepsis or bacterial superinfection. Superinfection with pathogens such as Acinetobacter baumanii and Apergillus fumigatus have been described. |

| Do not routinely administer systemic steroids. |

PPE: personal protective equipment.

The protection of medical personnel is a priority, and they must be given adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and be trained in donning and doffing techniques. Medical staff must perform hand hygiene before and after contact with the patient, particularly before donning and after doffing PPE. The minimum recommended PPE required in patients that are not scheduled for aerosol-generating procedures consists of a fluid resistant gown, FFP2 mask, gloves, splash-proof eye protection and head cover.

Protective measures should be maximised when caring for patients with confirmed infection, in critically ill patients with a high viral load, and in patients that require invasive aerosol-generating procedures and manoeuvres such as aerosol therapy and nebulisation, aspiration of respiratory secretions, bag-mask ventilation, non-invasive ventilation, intubation, respiratory sampling, bronchoalveolar lavage, tracheostomy or cardiopulmonary resuscitation.17,18 Hospitals must:

- –

Plan procedures in advance to make sure all barrier precautions are in place and to prepare the material needed. It is important to avoid unnecessary delays in invasive ventilation.

- –

Minimise the number of exposed staff.

- –

PPE: the aim is to protect staff from inhalation and contact with aerosols and droplets that can be generated during the procedure. PPE elements that can achieve this level of protection include: N95 or preferably FFP3 respirator, close-fitting goggles or full face shield, fluid resistant gown, gloves, fluid resistant head and shoe covers. Two aspects of PPE use are particularly important: ensuring the mask is correctly sealed and double-gloving, using a clean inner glove to reduce the possibility of touching contaminated material by hand when removing the PPE. Correct hand hygiene should always be performed before donning and after doffing the PPE.

- –

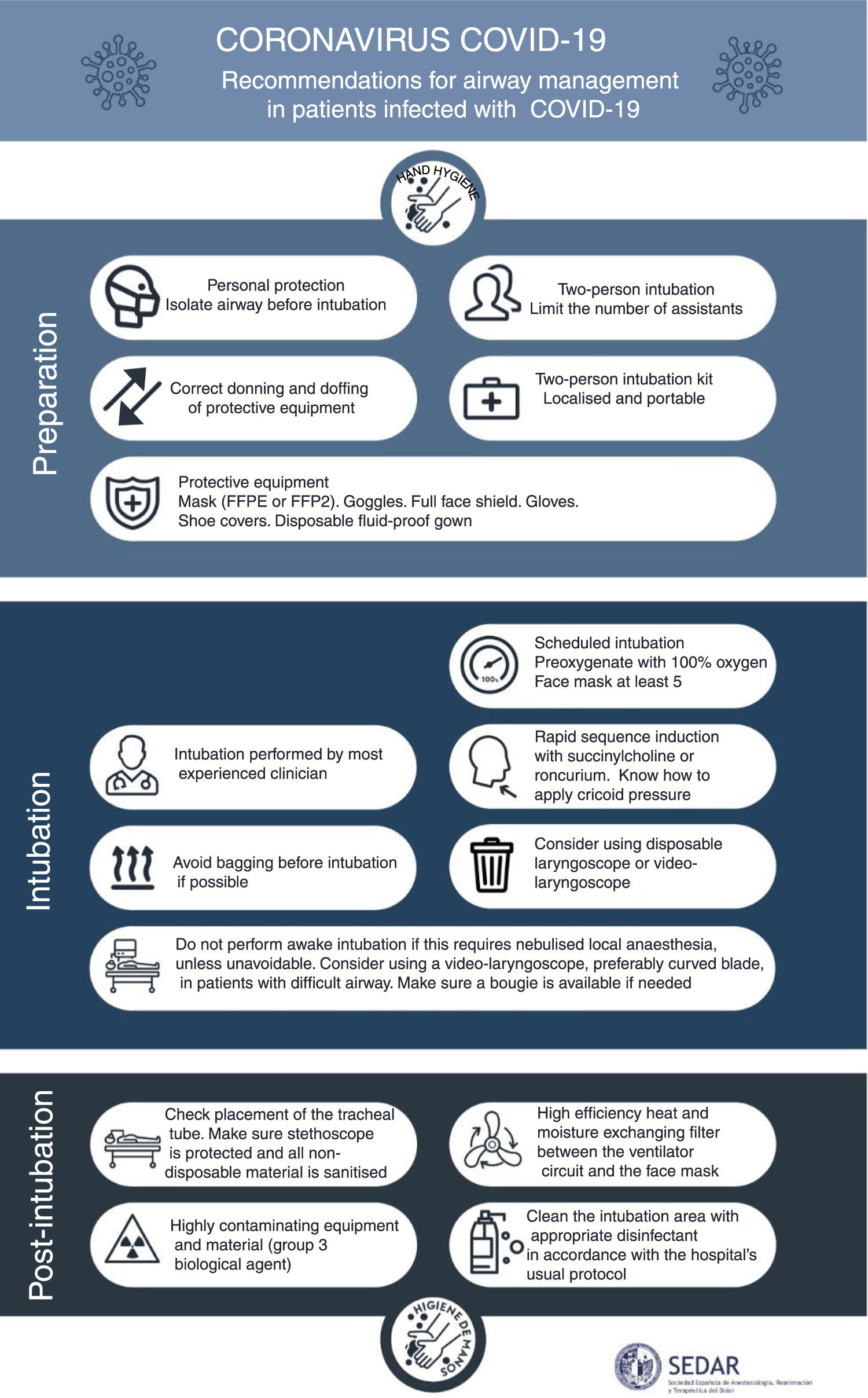

If tracheal intubation is required, it must be performed by the clinician with most experience in airway management (Fig. 1). Unless specifically indicated, awake intubation under fibreoptic vision and nebulised airway anaesthesia must be avoided. Make sure a high efficiency heat and moisture exchanging filter is placed between the face mask and the ventilation circuit before starting pre-oxygenation. Perform rapid sequence induction with adequate cricoid pressure. Avoid bag-mask ventilation before intubation as far as possible; if required, ensure the mask is correctly sealed to prevent leakage and administer small tidal volumes. It is advisable to perform intubation under video laryngoscopy. Use subglottic secretion drainage endotracheal tubes whenever possible to reduce the risk of bacterial superinfection. Place high efficiency heat and moisture exchanging filters on the inspiratory and expiratory branches of the ventilator and avoid active humidification. After intubation, immediately remove all the material used and place it in a double-zipper plastic bag for proper disinfection.

- –

When removing PPE, take special care to avoid self-contamination; ideally, PPE should be removed under supervision.

- –

To clean the environment, follow the recommendations of the hospital's Preventive Medicine Service, paying particular attention to any surfaces that might be contaminated.

For more information on protection measures, consult the supplementary material in the article published by Bouadma et al. (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00134-020-05967-x).18

Recommendations for intraoperative managementIf a patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 requires surgery, transfer to the operating room will be carried out following all the precautionary measures previously described for the health personnel in charge of the transfer (PPE with FFP2 and preferably FFP3 mask if the distance between the patient and the staff is less than 2m). Dedicated transfer routes should be used or the number of staff present should be minimised. Patients must wear a surgical mask. Ideally, the operating room must be equipped with absolute or HEPA filtration (Table 2).

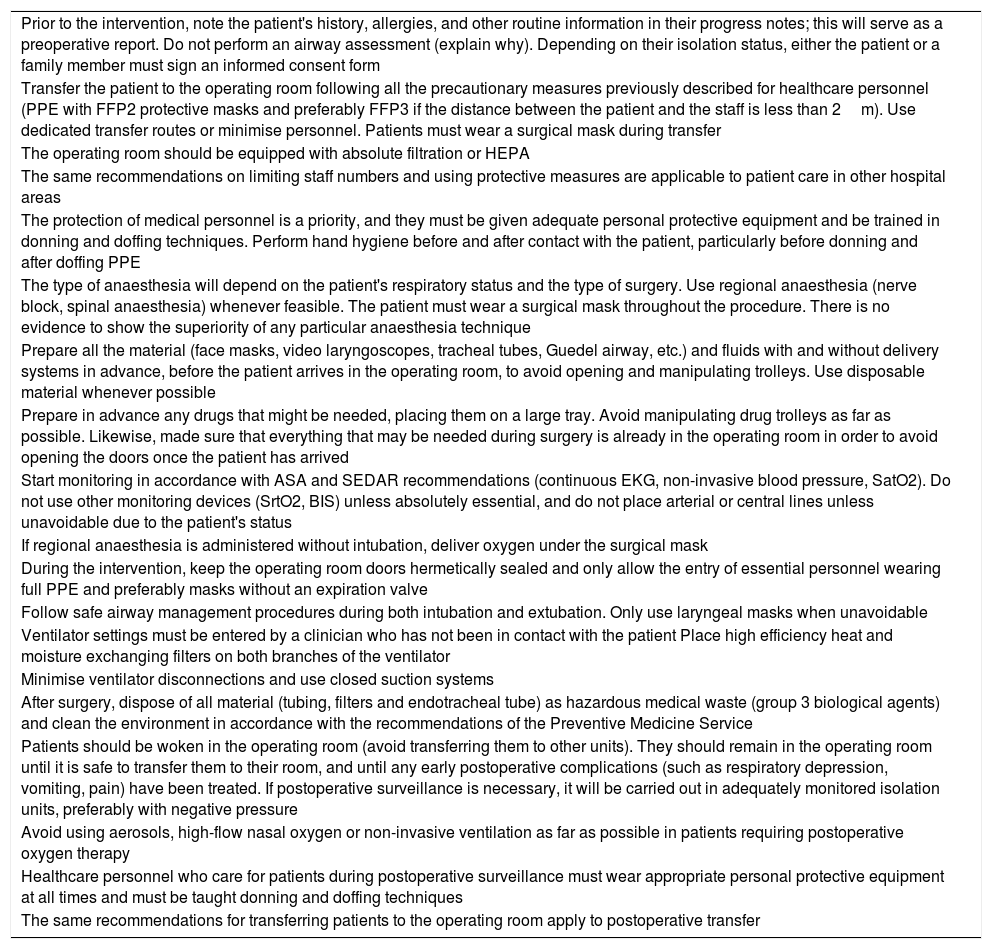

Recommendations for the intraoperative management of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection.

| Prior to the intervention, note the patient's history, allergies, and other routine information in their progress notes; this will serve as a preoperative report. Do not perform an airway assessment (explain why). Depending on their isolation status, either the patient or a family member must sign an informed consent form |

| Transfer the patient to the operating room following all the precautionary measures previously described for healthcare personnel (PPE with FFP2 protective masks and preferably FFP3 if the distance between the patient and the staff is less than 2m). Use dedicated transfer routes or minimise personnel. Patients must wear a surgical mask during transfer |

| The operating room should be equipped with absolute filtration or HEPA |

| The same recommendations on limiting staff numbers and using protective measures are applicable to patient care in other hospital areas |

| The protection of medical personnel is a priority, and they must be given adequate personal protective equipment and be trained in donning and doffing techniques. Perform hand hygiene before and after contact with the patient, particularly before donning and after doffing PPE |

| The type of anaesthesia will depend on the patient's respiratory status and the type of surgery. Use regional anaesthesia (nerve block, spinal anaesthesia) whenever feasible. The patient must wear a surgical mask throughout the procedure. There is no evidence to show the superiority of any particular anaesthesia technique |

| Prepare all the material (face masks, video laryngoscopes, tracheal tubes, Guedel airway, etc.) and fluids with and without delivery systems in advance, before the patient arrives in the operating room, to avoid opening and manipulating trolleys. Use disposable material whenever possible |

| Prepare in advance any drugs that might be needed, placing them on a large tray. Avoid manipulating drug trolleys as far as possible. Likewise, made sure that everything that may be needed during surgery is already in the operating room in order to avoid opening the doors once the patient has arrived |

| Start monitoring in accordance with ASA and SEDAR recommendations (continuous EKG, non-invasive blood pressure, SatO2). Do not use other monitoring devices (SrtO2, BIS) unless absolutely essential, and do not place arterial or central lines unless unavoidable due to the patient's status |

| If regional anaesthesia is administered without intubation, deliver oxygen under the surgical mask |

| During the intervention, keep the operating room doors hermetically sealed and only allow the entry of essential personnel wearing full PPE and preferably masks without an expiration valve |

| Follow safe airway management procedures during both intubation and extubation. Only use laryngeal masks when unavoidable |

| Ventilator settings must be entered by a clinician who has not been in contact with the patient Place high efficiency heat and moisture exchanging filters on both branches of the ventilator |

| Minimise ventilator disconnections and use closed suction systems |

| After surgery, dispose of all material (tubing, filters and endotracheal tube) as hazardous medical waste (group 3 biological agents) and clean the environment in accordance with the recommendations of the Preventive Medicine Service |

| Patients should be woken in the operating room (avoid transferring them to other units). They should remain in the operating room until it is safe to transfer them to their room, and until any early postoperative complications (such as respiratory depression, vomiting, pain) have been treated. If postoperative surveillance is necessary, it will be carried out in adequately monitored isolation units, preferably with negative pressure |

| Avoid using aerosols, high-flow nasal oxygen or non-invasive ventilation as far as possible in patients requiring postoperative oxygen therapy |

| Healthcare personnel who care for patients during postoperative surveillance must wear appropriate personal protective equipment at all times and must be taught donning and doffing techniques |

| The same recommendations for transferring patients to the operating room apply to postoperative transfer |

General or regional anaesthesia? No clear recommendation can be given in this regard. The choice of technique will depend on the patient's respiratory symptoms, such as coughing and expectoration, and the type of surgery required. If surgery is performed using regional anaesthesia without intubation, intraoperative oxygen therapy should be used, placing a surgical mask over the Ventimask® or the nasal cannulas.

The personnel safety and protective measures described should be followed during both intubation and extubation, using an appropriate PPE with a N95 respirator or FFP3 mask, bearing in mind that these procedures involve a high risk of aerosolization. High efficiency heat and moisture exchanging filters should be placed on the inspiratory and expiratory branches of the ventilator. During the intervention, the operating room doors should remain hermetically sealed and only essential personnel should be allowed inside, wearing full PPE and preferably masks without an expiration valve, since these are unsuitable for sterile environments. Ventilator disconnections should be minimised, and closed suction systems should be used. After surgery, once the patient has left the operating room, the ventilator tubing and filters should be discarded, and the operating room cleaned following the recommendations of the hospitals’ Preventive Medicine Service, paying particular attention to any surfaces that might be contaminated.

Patients should be woken in the operating room (avoid transferring them to other units). They should remain in the operating room until it is safe to transfer them to their room, and until any early postoperative complications (such as respiratory depression, vomiting, pain) have been treated. If post-anaesthesia surveillance is required, it should be performed in an isolation room (preferably negative pressure) or in other adequately monitored units that have been set aside specifically for COVID-19 patients. Healthcare personnel caring for these patients should wear full PPE with FFP2 or FFP3 masks at all times, depending on the type of care that is performed, as discussed above.

In patients requiring postoperative oxygen therapy, the use of aerosols, high-flow nasal oxygen or non-invasive ventilation should be avoided as far as possible. Patients that have been extubated in the operating room must wear a surgical mask over the Ventimask® or nasal oxygen cannulas used for the administration of oxygen therapy during transfer from the operating room to the hospital unit set aside for postoperative surveillance.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Montero Feijoo A, Maseda E, Adalia Bartolomé R, Aguilar G, González de Castro R, Gómez-Herreras JI, et al. Recomendaciones prácticas para el manejo perioperatorio del paciente con sospecha o infección grave por coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2020;67:253–260.