Malignant eccrine spiradenoma (MES) is a rare malignancy of the eccrine sweat glands. It usually presents as a small, firm, reddish painful and small solitary nodule. Head and neck are rare locations. Etiology is unknown although previous trauma is believed to be an implicated factor. MES arises over a prior benign spiradenoma. Clinical behavior is aggressive with a high rate of recurrences and distant metastases. Prognosis is poor. Diagnosis is based on histological findings and treatment must be aggressive from the beginning to achieve the best results.

Since Kersting and Helwig first described the case in 1956, and Beekley et al., reported its malignant transformation in 1971, only a few cases can be found in the literature.

Based on these particular features we report a case of a 75-year-old man diagnosed on a MES that arises in a very unusual location, with a peculiar histopathology and behavior.

El espiradenoma ecrino maligno (EEM) es un tumor maligno poco frecuente de las glándulas sudoríparas ecrinas. Suele presentarse como un pequeño nódulo eritematoso, firme, solitario y doloroso. La cabeza y el cuello son una localización excepcional. Se desconoce la etiología aunque se considera que un traumatismo previo es un factor implicado. El EEM se origina sobre un espiradenoma benigno previo. La conducta clínica es agresiva con una elevada tasa de recidivas y metástasis a distancia. El pronóstico es infausto. El diagnóstico se basa en los hallazgos histológicos y el tratamiento ha de ser agresivo desde el principio para obtener los mejores resultados.

Desde que, en 1956, Kersting y Helwig describieran el primer caso, y, en 1971, Beekley y cols. documentaran su transformación maligna, sólo se han publicado unos pocos casos.

En función de estas características específicas, describimos a un hombre de 75 años de edad, en el que se estableció el diagnóstico de este tumor, originado en una localización poco habitual, con una histopatología y conducta peculiares.

Eccrine spiradenoma is an uncommon and slow growth tumor of the eccrine sweat glands.1–3 It usually presents as a small, firm, reddish painful and small solitary nodule. Head and neck are rare locations.3,4 Etiology is unknown although previous trauma is believed to be an implicated factor.5,6

Since Beekley et al.,7 in 1971, first described malignant transformation of this tumor, less than 50 cases have been reported in the literature.2–6,8–10 Clinical behavior is aggressive with a high rate of local recurrences and distant metastases. Diagnosis is based on histopathological findings. Wide local excision associated with cervical neck dissection is the elective treatment.6,11 We now report a peculiar case of a malignant eccrine spiradenoma that arises, after surgical excision of a prior benign lesion, with an unusual behavior and histological features.

Case reportA 75-year-old man was referred to our Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department with a lesion in the nasolabial fold (Fig. 1) diagnosed histologically as a malignant eccrine spiradenoma, after three surgical excisions in another Surgery Department.

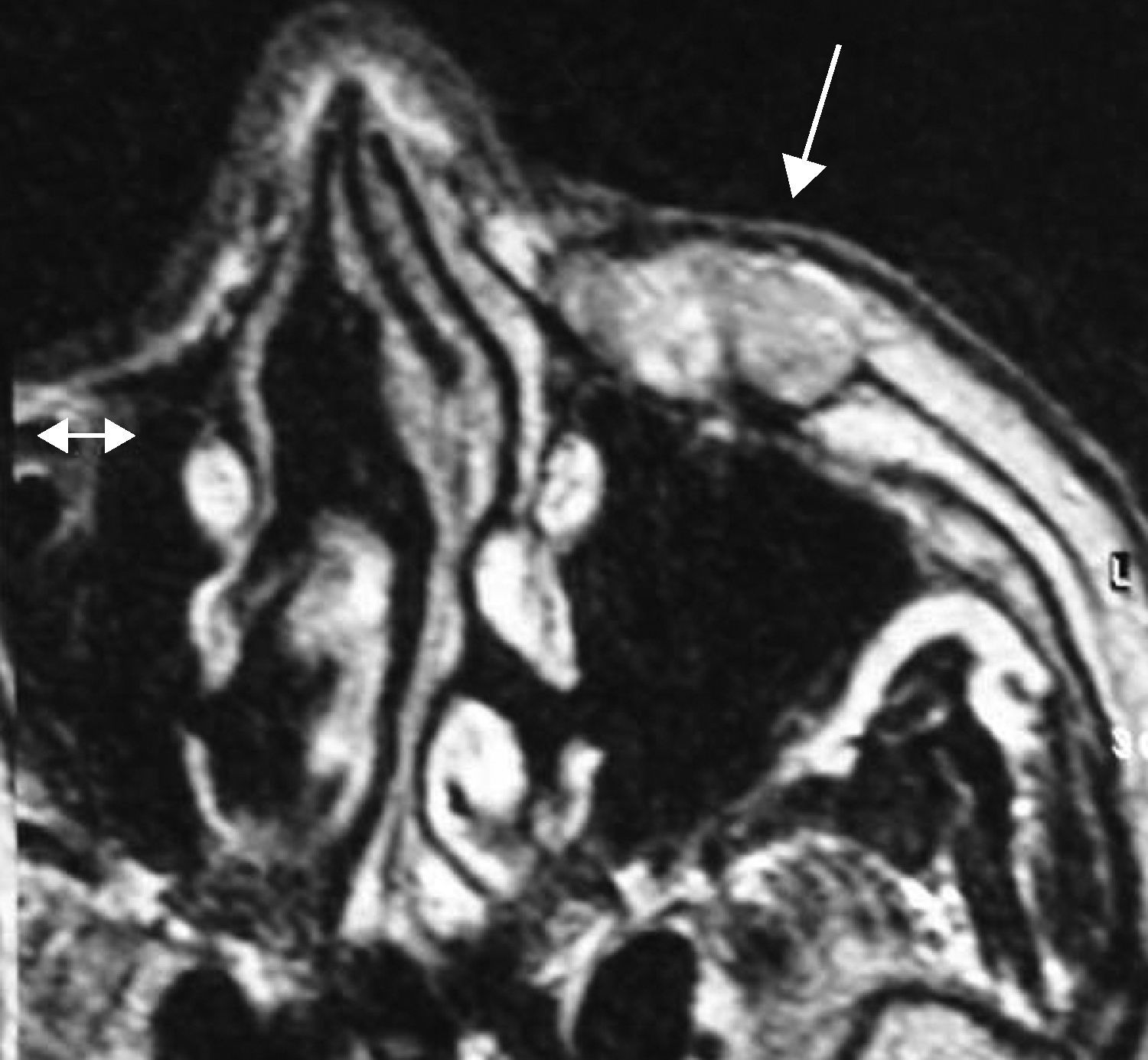

According to the diagnosis, a MRI and a radionuclide bone scan were performed. A 2.7×2.3×2.1cm nodular and bad defined lesion was located in the left zygomatic area infiltrating skin and subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 2) as well as four metastatic lesions in the occipital, right temporal, sphenoid and superior edge of the left scapula.

The tumor was diagnosed as a malignant eccrine spiradenoma stage IV so that palliative treatment with chemotherapy was performed. Partial bone response was obtained since radiological point of view but primary tumor kept on growing.

Although tumoral stage was advanced, we decided, according to the patient, performing a radical surgery treatment. Then, a FNAC of the primary lesion confirmed the diagnosis and a wide surgical excision of the tumor with neck dissection and reconstruction with a cervicopectoral flap was planned.

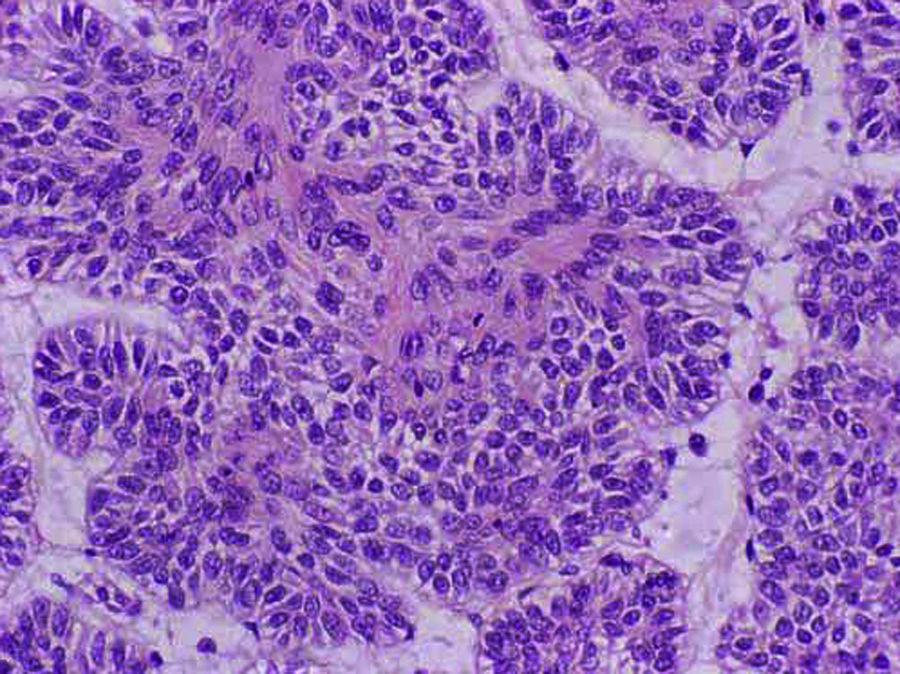

Histopathological examination revealed an encapsulated tumor composed by two cell types disposed in solid groups and areas with glandular, squamous and even sarcomatoid differentiation. Mitosis rate was so high and wide necrotic areas were frequently seen. The capsule had tumoral invasion foci (Fig. 3).

No one of the twelve cervical lymph nodes isolated was infiltrated by the tumor.

Eight months later, the patient presented a recurrence on the cervicopectoral scar, near the lips. According to this, a new resection was performed again obtaining histological free margins (Fig. 4).

Nowadays, three years after last surgery there have been no signs of local recurrences and metastatic lesions have been controlled by chemotherapy (Fig. 5).

DiscussionThis report tries to make a special emphasis concerning a proper management of eccrine spiradenoma, frequently benign, but, as in our case and due to an incorrect initial management, sometimes malignant. Since Kersting and Helwig first described the case in 1956,9 and Beekley et al.,7 reported its malignant transformation in 1971, only a few cases can be found in the literature.2–6,8–10

Eccrine spiradenoma is usually benign and may occur in infancy but most commonly arises in young people (2nd to 4th decades) as a small, firm and reddish painful solitary nodule (0.5–3cm), although bigger tumors have been described (10cm).1,3,8,9 Ulceration is extremely infrequent.1,5

Malignant form of eccrine spiradenoma (MES) is extremely infrequent and only 50 cases have been reported in the literature. It may develop de novo or most frequently, arises in pre-existing benign eccrine spiradenoma as a sudden growth or pain in people over 50 years old after a variable latent period (may be as long as 75 years), with no gender differences.2,4,6,8,9,12,13 It tends to preferentially involve trunk and extremities (92% of reported cases) and head and neck presentation is extremely rare, as in our case.12

Multiple cases have been described associated with other neoplasms as cylindromas, hidradenomas or trichoepitheliomas into the Brooke–Spiegler syndrome. In these cases, lesions combine features of both cylindromas and spiradenomas.1,4,5,8

Since MES has an aggressive clinical behavior and a high rate of local recurrences (32–58%) and distant metastases to the lymph nodes (35–44%), bone and lung,2,4,8,14 a proper management should begins with a proper diagnosis based on histopathological findings.

Such findings include proliferation of atypical cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, increased mitoses, nuclear pleomorphism and loss of periodic acid-Schiff-positive basement membrane and loss of the typical dual cell population disposed in cords.3–6,8,10,12,13

Another microscopic features may be present as areas of necrosis, focal squamous differentiation, invasion of the surrounding tissues and increased vascularization of the tumor. The last condition can lead to diagnostic confusion with a vascular neoplasm.12

Immunohistochemically, MES exhibit variable expression of cytokeratins, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen and S100 protein. Overexpression of p53 protein in benign spiradenomas has been associated with malignant transformation, usually into a carcinoma; however, carcinosarcomatous transformation has also been reported.12

Areas of spiradenoma near or in transition with a malignant tumor such as rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and chondrosarcoma may be present although less frequently.4,8

All these variable and inconstant histological features can lead to a mistaken diagnosis with other skin malignances6,13 such as carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, clear cell hidradenoma or malignant condroid syringoma.8 So, we emphasize to make a correct and close histological examination in order to avoid incorrect treatments.

The mainstay of therapy is surgical excision, which may be curative in some cases.12 According to our experience and the medical literature, every tumor diagnosed as eccrine spiradenoma should be widely resected even benign, in order to prevent malignization and local recurrences.1,2,5,8,9

Cervical lymph nodes should be dissected if tumor metastases are suspected clinically to complete the treatment if cervical disease is present and to prevent lympathic spread if the neck is staged as N0.2,4,6,11,12

The usefulness of other therapeutic alternatives such as hormonal therapy with tamoxifen, chemotherapy and radiotherapy remains to be determined2,4–6,8,9,11 and they have been used unsuccessfully in the treatment of these patients.6

We do not agree with these thoughts, based on our clinical case. As described above, the patient was diagnosed on MES stage IV with bone metastases. He received six cycles of CDDP-5-FU-folinic acid obtaining an almost complete bone response. This finding should represent a new chemotherapy schedule useful in selected cases.

MES usually metastasizes to regional lymph nodes and less frequently to lung, brain and liver. While distant metastases are uncommon, they generally portend an ominous prognosis.12 In spite of this condition, it is noticeable that our patient is still alive despite he was initially presented with bone distant metastases.

The overall prognosis is so poor that Meyer et al.8 reported survivals of 36 months after diagnosis with a mortality rate of 22%. Other authors as Herzberg et al.11 find a mortality rate of 20%.

It is noticeable that our patient, three years after the last surgery, keeps still alive with a good quality of life. Nevertheless, postoperative long-term follow-up is necessary in all the patients to prevent any local or metastatic recurrence.6

ConclusionsWe are face to face with a rare tumor of the eccrine sweat glands. Malignant forms are extremely uncommon although described. Diagnosis is complicated and is based on histological findings. Recurrences after treatment are frequent and often occur after incomplete tumor excisions so that aggressive surgical treatment must be performed although the tumor is benign.

Conflict of interestThe authors state that there are no conflicts of interest in writing this article.