Recently, we have witnessed the increasing use of surgical treatment of forearm fractures in children. Although older surgeons tend not to operate on what does not need to be operated on, younger surgeons are increasingly resorting to surgical methods. Disagreements can often be noticed among colleagues about the indication when surgical treatment should be approached. In addition to disagreements in the choice between conservative and surgical treatment, we are increasingly noticing disagreements in the conservative approach. In some cases, some advocate closed reduction, while others do not. Other centres are also recording an increase in surgical treatment, but at the same time there is an increase in the number of complications.1 Studies have shown an increase in delayed union, the need to frequently expose the fracture site, and wound problems.2,3 Rates of superficial infections are significantly more common than deep ones, which are associated with open fractures. Postoperative neuropraxia usually occurs transiently, without permanent deficits. Delayed union are more common in adolescents than in younger children. Neither the possibility of Extensor Pollicis Longus (EPL) rupture nor the possibility of postoperative compartment syndrome should be neglected.4–6 Generally, as greater indications for surgery are unstable and irreducible fractures, open fractures, fractures with neurovascular compromise, pathologic fractures and forearm fractures with associated humerus fracture (“floating elbow”).7 While there is no doubt that surgical techniques have brought advances in the treatment of forearm fractures in children, we need to know when there is an indication for the same. We must not forget that any bone manipulation in childhood requires general anaesthesia, which should be avoided if we do not have a clear indication. It is also important to note that surgical treatment, and consequently possible complications, is much more financially expensive than a conservative approach.

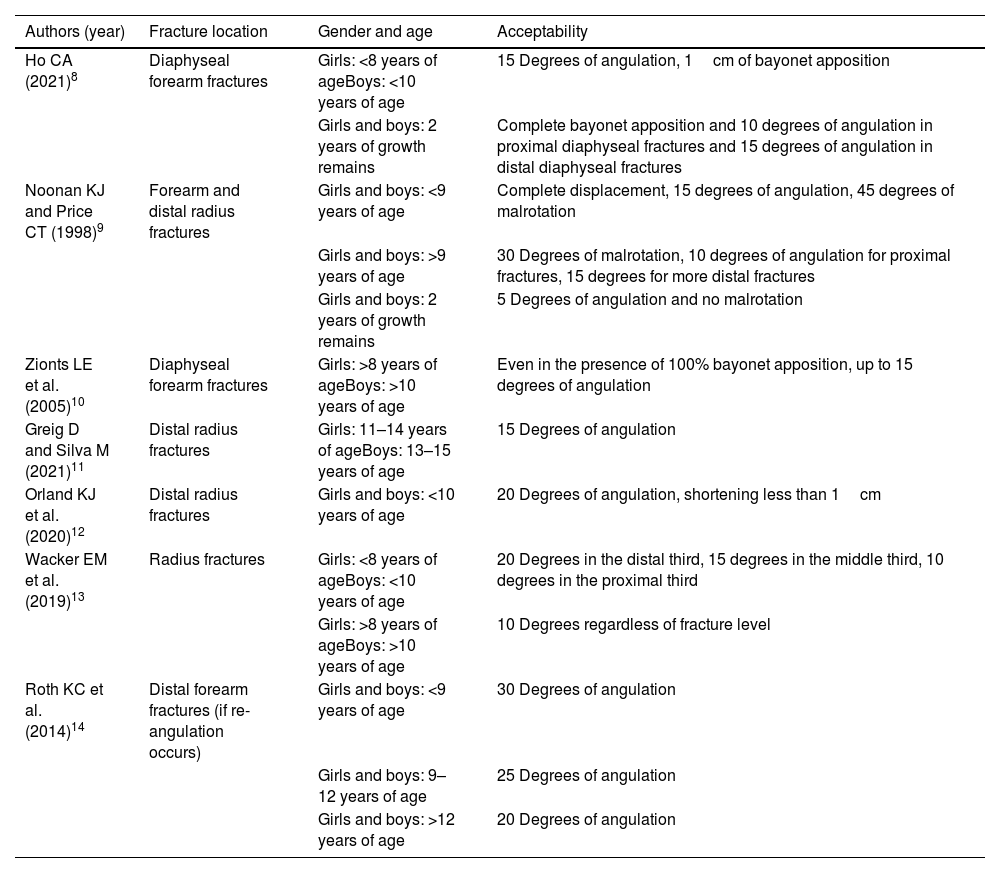

Based on evidence-based medicine, we approached the PubMed database search using the following terms: (angulat* OR angle) AND (accept* OR tolera*) AND fracture AND (child* OR paediatric* OR paediatric*) AND (forearm OR radius OR ulna). Reading the articles, we selected those of interest that clearly indicate to us within which values it is not necessary to resort to closed reduction or surgical treatment (Table 1).

Acceptability for conservative (non-closed reduction and non-operative) treatment of forearm fractures in children.

| Authors (year) | Fracture location | Gender and age | Acceptability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ho CA (2021)8 | Diaphyseal forearm fractures | Girls: <8 years of ageBoys: <10 years of age | 15 Degrees of angulation, 1cm of bayonet apposition |

| Girls and boys: 2 years of growth remains | Complete bayonet apposition and 10 degrees of angulation in proximal diaphyseal fractures and 15 degrees of angulation in distal diaphyseal fractures | ||

| Noonan KJ and Price CT (1998)9 | Forearm and distal radius fractures | Girls and boys: <9 years of age | Complete displacement, 15 degrees of angulation, 45 degrees of malrotation |

| Girls and boys: >9 years of age | 30 Degrees of malrotation, 10 degrees of angulation for proximal fractures, 15 degrees for more distal fractures | ||

| Girls and boys: 2 years of growth remains | 5 Degrees of angulation and no malrotation | ||

| Zionts LE et al. (2005)10 | Diaphyseal forearm fractures | Girls: >8 years of ageBoys: >10 years of age | Even in the presence of 100% bayonet apposition, up to 15 degrees of angulation |

| Greig D and Silva M (2021)11 | Distal radius fractures | Girls: 11–14 years of ageBoys: 13–15 years of age | 15 Degrees of angulation |

| Orland KJ et al. (2020)12 | Distal radius fractures | Girls and boys: <10 years of age | 20 Degrees of angulation, shortening less than 1cm |

| Wacker EM et al. (2019)13 | Radius fractures | Girls: <8 years of ageBoys: <10 years of age | 20 Degrees in the distal third, 15 degrees in the middle third, 10 degrees in the proximal third |

| Girls: >8 years of ageBoys: >10 years of age | 10 Degrees regardless of fracture level | ||

| Roth KC et al. (2014)14 | Distal forearm fractures (if re-angulation occurs) | Girls and boys: <9 years of age | 30 Degrees of angulation |

| Girls and boys: 9–12 years of age | 25 Degrees of angulation | ||

| Girls and boys: >12 years of age | 20 Degrees of angulation |

If we adhere to the above data, the need for closed reductions and operative treatments will undoubtedly be reduced in everyday practice, with an equally functional outcome and less stress for the child.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Conflict of interestThe author declares that have no conflicts of interest.