Bullfighting festivals are attributed to the cultural idiosyncrasies of the Ibero-American people, posing an extreme risk to the physical integrity of the participants. Spain is considered the country with the highest number of bull-related celebrations worldwide and, therefore, with the highest number of patients injured by bullfighting trauma treated, thus justifying a public health problem. The generalities associated with this type of trauma define the people injured as polytraumatised patients. In addition, it is important to know the kinematics of the injuries and their specific characteristics, in order to implement quality medical–surgical care.

MethodsScientific review of the literature to promote a comprehensive guide for the medical–surgical management of patients injured by bullfighting trauma.

ResultsWe described the guidelines to standardise protocols for in-hospital approach of patients injured by bullfighting trauma.

ConclusionsBullfighting trauma is considered a real health problem in the emergency departments of the ibero-Americans countries, especially in Spain, where bullfighting is part of the national culture. The inherent characteristics of these animals cause injuries with special aspects, so it is important to know the generalities of bullfighting trauma. Because of the multidisciplinary approach, these guidelines are adressed to all healthcare providers involved in the management of these patients. It is essential to establish particular initial care for this type of injury, specific therapeutic action and follow-up based on the medical–surgical management of the trauma patient in order to reduce the associated morbidity and mortality.

Los festejos taurinos forman parte de la idiosincrasia cultural propia de los pueblos iberoamericanos, suponiendo un riesgo extremo para la integridad física de los participantes. España es considerado el país con mayor celebración de festejos taurinos a nivel mundial y, por ende, con mayor número de pacientes heridos por traumatismo taurino atendidos, justificando así una cuestión de salud pública. Las generalidades asociadas a este tipo de traumatismos definen a los heridos como pacientes politraumatizados. Es importante conocer la cinemática de las lesiones y sus características específicas, para implantar una atención médico/quirúrgica integral de calidad.

Objetivos y métodosPromover una guía para el abordaje y el manejo médico/quirúrgico integral del paciente herido por traumatismo taurino, mediante la revisión de la literatura.

ResultadosSe describieron las líneas de actuación para estandarizar los protocolos de atención al paciente herido por traumatismo taurino en el ámbito hospitalario.

ConclusionesEl traumatismo taurino supone una problemática de salud en las urgencias hospitalarias de los países iberoamericanos, especialmente en España, donde la tauromaquia forma parte de la cultura nacional. Las características inherentes a estos animales ocasionan lesiones con aspectos especiales, por lo que es importante conocer las generalidades de los traumatismos taurinos. Debido a su atención multidisciplinar, esta guía va dirigida a todos los profesionales sanitarios implicados en el manejo asistencial de estos pacientes. Para disminuir la morbimortalidad asociada, es fundamental establecer ante este tipo de lesiones una atención inicial particular, una actuación terapéutica específica y un seguimiento basados en la atención médico/quirúrgica al paciente politraumatizado.

Bullfighting festivals are attributed to the cultural idiosyncrasies of the Ibero-American people, posing an extreme risk to the physical integrity of the participants.

In Spain approximately 20,000 bullfighting festivals are celebrated annually. The Community of Valencia celebrates nearly 10,000 of them annually and specifically the province of Castellón celebrates over 7000 events each year, with these regions being considered the ones with the most bullfighting activities worldwide.1

Popular bullfighting events (popular celebrations or “bous al carrer”) are the most common setting in Spain, where the encounter between fighting bulls and bullfighters takes place. These are fully integrated into the celebration, accompanied by excesses in terms of food and drink (mostly alcoholic), together with less surgically prepared health personnel and fewer resources compared to professional events, creating a situation prone to accidents without regulated assistance, and one which represents a real major health problem.

All bullfighting (high-energy) trauma is included in the category of incised-contused wounds that must be considered by definition dirty or contaminated (where all types of microorganisms are isolated),2 which can have several entry/exit holes and multiple trajectories leading to large tissue damage and which potentially often lead to associated injuries, with visceral, vascular and osteoligamentous injuries not being uncommon.3

Furthermore, the specific characteristics and kinematics of bull horn injuries define the people who suffer from them as polytraumatised patients, so it is important to know the generalities of bullfighting trauma and establish a particular initial care, a specific therapeutic action and follow-up based on medical–surgical care for the polytraumatised patient, reflected in the ATLS (Advanced Trauma Life Support) and DSTC (Definitive Surgery for Trauma Care) protocols.4,5

The main objectives of this study are to make these injuries and their possible complications more visible; to achieve quality care and a reduction in morbidity and mortality, and to promote actions that standardise the care protocols for patients injured by bullfighting in the hospital setting.

Concept and classification of bull horn woundsConceptThe injury caused by a bull's horn affects tissues and structures in a certain area of the body. If it entails significant vascular, visceral and/or nerve involvement, it is considered complicated.6

ClassificationWe can also differentiate between several types of traumas, depending on the tissue damage caused by the bull's horn.

We differentiate between contusions: defined by the injury to the skin and the subcutaneous cellular tissue:

- •

Jab: simple contusion, with dermo-epidermal abrasion due to friction without penetration by the horn. This occurs when the horn reaches the victim's body tangentially.

- •

Puncture: the horn reaches its victim obliquely or perpendicularly, causing a shallow break in continuity, without penetrating the fascia. If it has several trajectories, it is called a continuous puncture.

Gorings are when injuries pass through the fascia:

- •

Penetrating: wounds that cause injuries beyond the fascial plane.

- •

Misleading: the location of the injury is far removed from the entry site due to its long trajectory and the severity goes unnoticed.

- •

Closed or sheathed: those that without obvious skin injury, are able to injure deep structures.

- •

Gloved: these occur when the injured person wears clothing with a much greater elasticity than the skin. The horn produces an injury beyond the fascial plane wrapped in the injured person's clothing without tearing it.

Injuries are also classified according to their severity7:

- •

Group 1 or mild injuries: those that do not pose a life-threatening risk to the patient or cause subsequent sequelae. They can be examined in the infirmary.

- •

Group 2 or moderate/severe injuries: they do not pose an immediate life-threatening risk to the patient but have a high morbidity rate. They require urgent surgery and/or hospitalisation.

- •

Group 3 or very severe injuries: those that compromise the patient's life and require urgent surgery under general anaesthesia.

As previously mentioned, a patient injured by bull horns must be considered a polytrauma patient, following the same care guidelines reflected in the ATLS and DSTC protocols.

Criteria for activation of the Immediate Care Unit for Trauma (UAIT)- •

Priority 0 (vital signs):

- ∘

Glasgow (no sedation): ≤13.

- ∘

Systolic blood pressure: <90mmHg.

- ∘

Respiratory rate: <10 or>29breaths per minute; or need for ventilatory support.

- ∘

Active bleeding.

- •

Priority 1 (injury anatomy):

- ∘

Penetrating wound to the head-neck, torso and limbs proximal to the elbow/knee.

- ∘

Unstable thorax.

- ∘

Two or more proximal fractures of long bones.

- ∘

Amputation proximal to the wrist/ankle. Catastrophic limb.

- ∘

Pelvic fracture.

- ∘

Open or depressed cranial fractures.

- ∘

Paralysis of limbs.

- ∘

Burns>15% of body surface area.

- ∘

Positive FAST.

Other potentially dangerous circumstances or situations should be taken into account:

- •

Priority 2 (depending on the injury mechanism):

- ∘

Multiple bruises from the attack

- •

Priority 3 (special situations):

- ∘

Elderly, children, patients on anticoagulants or with blood dyscrasias, burns, pregnancy of >20 weeks.

Any patient injured by a bull's horn who presents with the before-mentioned characteristics will be treated in the first instance in the emergency room, under the same procedures and by the same medical team as those recorded in the clinical guidelines for the management of polytraumatised patients.

If the patient does not meet the requirements established for UAIT activation, the on-call general surgeon will be notified for assessment, together with the surgical especialties personnel, depending on the type of injury.

Hospital services and responsibilitiesAfter initial patient care, the focus must be on the patient's main treatment and on hospital follow-up. We propose the following scheme:

General surgery and digestive system surgery- •

Initial and main management of the patient with bullfighting trauma.

- •

Injuries affecting the following areas:

- ∘

Cervical.

- ∘

Axillary.

- ∘

Thoracic-abdominal-pelvic.

- ∘

Inguinal.

- ∘

Perianal (including buttocks).

- •

Skin and soft tissue lesions of any location that do not affect noble structures, as well as lesions of this nature that have already been assessed, treated and sutured by the bullfighting event surgeon and which do not require urgent surgical reassessment.

- •

Comprehensive management of the polytraumatised patient (multiple injuries affecting different organs and systems), provided that the main injury that led to hospital admission is the responsibility of the surgery department.

- •

Spinal cord and musculoskeletal trauma (osteotendinous, muscular and ligamentous injuries).

- •

Injuries affecting the extremities (both upper and lower) with vascular-nervous, osteoarticular/ligamentous/tendinous involvement and/or major muscle damage (avulsion, detachment, etc.).

- •

Trauma and maxillofacial injuries.

- •

Moderate/severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) following blunt trauma.

We would highlight the need to request assessment and provision from the different surgical services depending on the location of the injury for its specific treatment and follow-up (urology, gynaecology, ophthalmology, otorhinolaryngology, neurosurgery or vascular surgery). If intensive care is required, regardless of the injuries, an ICU is also needed. The inclusion of plastic surgery teams during follow-up for complex surgical reconstructions is also important.

In a similar manner to all pathologies, although one service will be primarily responsible for the patient, sometimes surgical management and follow-up will be carried out jointly and multidisciplinarily, depending on the associated injuries (interconsultations).

TreatmentGeneral treatment of patients wounded by bull hornsAs we have previously highlighted, the main management of these injuries must be guided by the ATLS protocols. The objective of primary assessment is the diagnosis and treatment of life-threatening injuries, using the X-ABCDE system for caring for polytraumatised patients. In many cases, penetrating wounds that are not immediately life-threatening are present, and to carry out the primary assessment, sterile compresses or dressings will be temporarily placed on the wound for later assessment.

The general treatment of bull horn wounds consists of turning a traumatic wound into a surgical wound. In all cases injured by bull horns, the following steps must be followed:

- •

Removal of the compress or dressing for irrigation of the wound with physiological saline solution and povidone iodine/chlorhexidine, in order to eliminate foreign bodies from the wound.

- •

Change of gloves and placement of sterile fields.

- •

Minor injuries can be examined and treated in the emergency department under local anaesthesia.

- •

Digital examination of the wound and the probable paths to incision planning:

- ∘

Correctly resect the skin edges and necrotic tissue with a (Friedrich) knife.

- ∘

Obtain wide exposure of the tissues.

- ∘

Resect all devitalised tissues.

- ∘

Obtain careful haemostasis.

- •

Taking a culture sample is recommended for bacteriological study.

- •

Reconstruction of the area by planes, always in the most anatomical and functional way possible (if >6h have passed, primary closure is not recommended).

- •

Placement of a drain in each of the trajectories with an exit through the most inclined site of the injury, considering the recumbent position that the injured person will maintain in the following 48h. The best drain to use is the non-aspiration Penrose type placed in a spindle shape. Suction drains (Redon, Jackson-Pratt or Blake type) will be used when deep cavities are to be drained, in areas rich in lymphatics or in the case of vascular wounds.

- •

All wounds are then sutured over the drains, using edge-to-edge sutures, with or without rotational muscle flaps, and can be sutured with 2/0 or 3/0 silk. Finally, the wound is covered with slightly compressive dressings.

- •

Tetanus vaccination is administered according to personal history and type of injury.

Bull horn wounds are potentially serious injuries, with a high risk of developing complications from infection. For this reason, management must be multidisciplinary in approach. After carrying out an exhaustive review of the literature, few studies analysed microbiological isolates after a wound caused by a bull horn. However, the vast majority conclude that these are polymicrobial infections in which it would be considered prudent to cover both gram-positive and negative bacteria as well as anaerobes.

Antibiotic treatment is based on the severity of the injury and the depth of the wound with invasion of deep planes and vascular structures that could compromise the patient's life8:

- -

Patients with mild forms who can be discharged home: oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875/125mg every 8h for 5 days.

- ∘

In patients allergic to beta-lactams: oral clindamycin 300mg every 8h for 5 days. Oral ciprofloxacin 750mg every 12h can be considered (individualised depending on the patient).

- -

Patients with mild/moderate forms requiring hospital admission: tigecycline 200mg (loading dose) followed by 100mg every 12h intravenously (IV) for 7–10 days, depending on clinical progress. Treatment should be started within the first 6h of admission to the emergency department.

- -

Patients with severe forms requiring hospital admission: peracillin–tazobacam 4.5g every 8h iv ±linezolid 600mg iv every 12h within the first hour after admission to the emergency department.

- ∘

This regimen will be maintained until 48h after the intervention and may subsequently be simplified to tigecycline 200mg (loading dose) followed by 100mg every 12h iv for 10–15 days (depending on clinical progress), or to targeted treatment based on microbiological isolates if available. Consider associating amikacin 15–20mg/kg/day (2–3 days).

- ∘

In patients allergic to beta-lactams: ciprofloxacin iv 400mg every 8h+metronidazole iv 500mg every 8h. Depending on the severity, consider adding linezolid 600mg every 12h iv±consider adding amikacin 15–20mg/kg/day (2–3 days).

As for the specific treatment based on the topography of the injuries, the following will be briefly described different algorithms for action based on the review of the guidelines for action reflected in the books on the care of polytraumatised patients (ATLS Manual 10th Edition American College of Surgeons and Manual of Algorithms for the Management of Polytraumatised Patients – Spanish Association of Surgery).9

Maxillofacial and cervical trauma and airway management (Fig. 1)Airway managementIn any bullfighting trauma, the airway may be compromised, which constitutes a vital medical–surgical emergency. Understanding any changes and detecting them is essential, together with having the necessary resources for airway control in all polytraumatised patients (Fig. 1).

Cervical traumaMost patients with cervical trauma who require surgical treatment for vascular or visceral injuries have suffered penetrating trauma. These are rare but potentially dangerous injuries due to the vascularisation of the area and the presence of the digestive tracts and airways.

Initial assessment consists of ruling out airway obstruction, taking all possible measures to protect the airway and associated injury to the cervical spine.

It is estimated that up to 50% of cervical trauma is associated with neurological morbidity to varying degrees, so all should be considered as potential spinal cord trauma until proven otherwise.

Maxillofacial traumaThese injuries are rare but are sometimes very dramatic and have high morbidity. Their severity is related to airway obstruction and/or the association of a TBI. All maxillofacial trauma should be assessed by maxillofacial surgery.

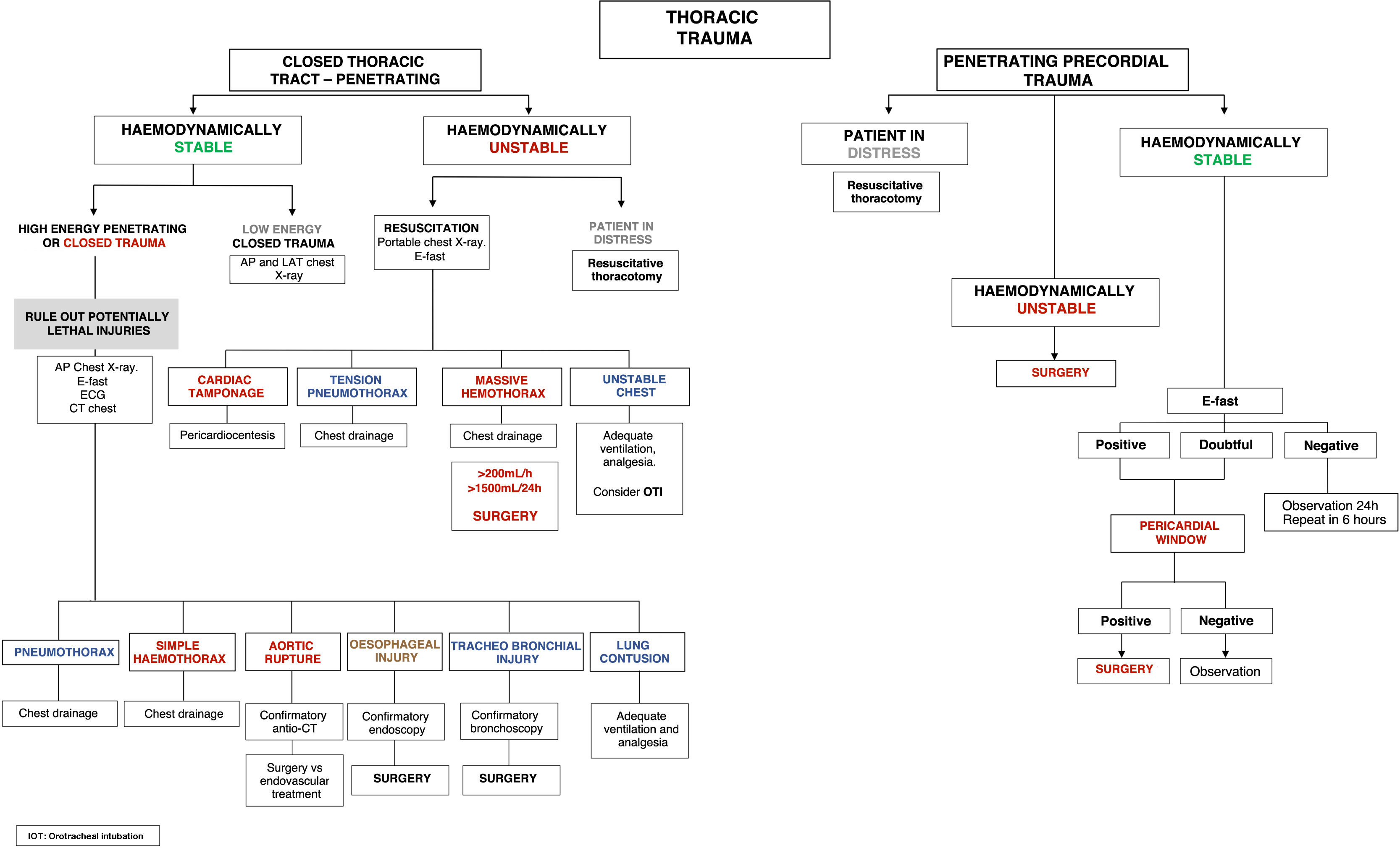

Thoracic trauma (Fig. 2)Thoracic trauma caused by fighting bulls is the leading cause of death at the scene of the incident, especially penetrating cardiac and large vessel trauma (Fig. 2).

Life-threatening injuries should be diagnosed and treated immediately. They can usually be controlled by controlling the airway and placing a chest drain (80% of cases).

Basically, there are two types of chest trauma: blunt or penetrating. The diagnostic–therapeutic algorithm will depend on the type of injury.

Abdominal trauma (Fig. 3)The abdominal cavity is one of the most frequently affected anatomical compartments in polytraumatised patients. In patients injured by bull horns, they are the second most frequently affected after lower limb injuries, representing up to 11% of the injured.1 However, they represent between 20% and 35% of the causes of death in these patients (Fig. 3).

Pelvic trauma (Fig. 4)These are serious pelvic traumas caused by high-energy injuries. In addition to the mechanism of injury, we should suspect it when there are perineal haematomas, haematuria, rectal bleeding or enlarged prostate. These traumas are frequently associated with other intra-abdominal injuries, so it is essential to clinically suspect other injuries when evaluating the patient (Fig. 4).

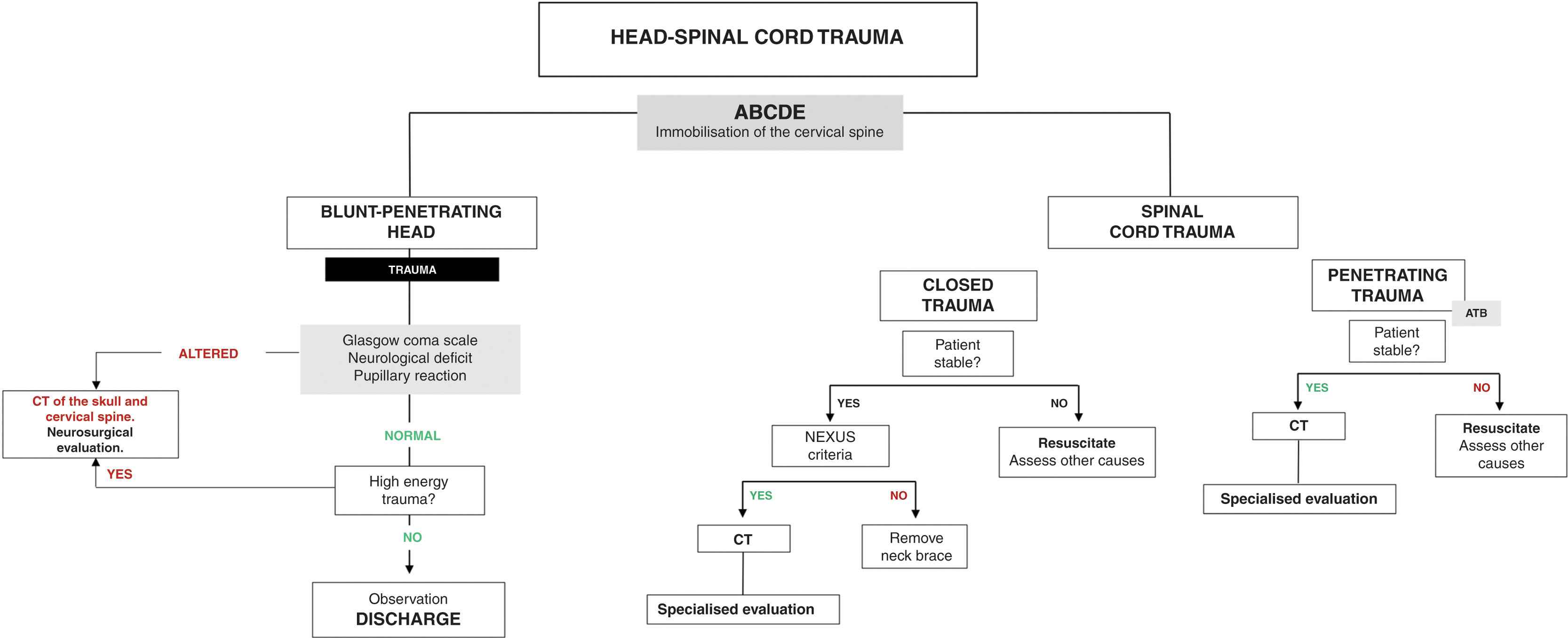

Head trauma (Fig. 5)Traumatic brain injuries are common in bullfighting. According to large series of injuries from bull horns, TBIs rank first in terms of morbidity and mortality. Mortality in polytraumatised patients increases depending on whether or not they suffer TBI (18.2% versus 6.1%)10,11 (Fig. 5).

The main objective of treating these traumas is to prevent cerebral ischaemia (the main cause of secondary brain damage) through rapid and effective treatment, stabilising the patient and identifying intracranial lesions that require urgent surgery.

It is very important to perform a neurological examination using the Glasgow scale and the assessment of pupillary reactivity.

Assess specific management according to the type of TBI, following the guidelines of the Clinical Pathway for the Management of Severely Traumatised Adult Patients. All patients with moderate or severe TBI should be assessed by neurosurgery.

Spinal cord trauma (Fig. 5)Traumatic spinal cord injury compromises bone and ligament structures, joint capsules, intervertebral discs and muscle structures. We must bear in mind that up to 5–25% of spinal cord injuries occur during transfer to the hospital due to poor immobilisation (the percentage is higher in those injured by bull horns due to the emergency transfer performed when exiting the bull ring).

Patients with spinal cord injuries may eventually present spinal cord shock, which resembles distributive shock with significant vasoplegia and even bradycardia with severe hypotension. This process can last from a few hours to 3–6 weeks after the trauma and the differential diagnosis must be made with hypovolemic shock.

In cases of suspected spinal cord injury, consult directly with the traumatology/neurosurgery service, in keeping with the spinal cord injury protocol.

Musculoskeletal and limb trauma (Fig. 6)Trauma to the limbs mostly involves injuries to the musculoskeletal system. They occur in 85% of cases of patients who have suffered blunt trauma and in more than 50% of penetrating trauma (Fig. 6).

The lower limbs are the main anatomical site affected by bull horn wounds, representing approximately 60% of injuries (affecting the muscular plane in almost 40%). The most frequent trauma injury patterns are closed fractures, although the percentage of open fractures associated with a penetrating injury is around 10%.1

Usually, these wounds appear highly dramatic due to their spectacular nature, but rarely do they represent a real risk to the patient's life or even to the limb itself (less than 5% of cases).

Immobilisation is the basic therapeutic principle of any limb trauma once the most important complications have been ruled out. It is very important to re-evaluate the neurovascular status after it has occurred. All musculoskeletal and limb trauma must be assessed by traumatology.

Currently, the safe definitive orthopaedic surgery (SDS) strategy is the most widely used in relation to the surgical treatment of an injured limb. This classification assesses clinical stability: “Fix and Flap” strategy (debridement and definitive fixation) in a stable patient; and damage control surgery (resuscitation and external fixation) in the case of instability.12 However, recently, a new orthopaedic management strategy, MuST, assesses a temporary musculoskeletal surgery approach in stable patients who associate injuries with poor local conditions (open fractures with high contamination, periarticular and/or high tissue destruction).13

Except in cases of catastrophic limb damage (irreparable vascular/nerve and soft tissue damage), amputation will be a joint decision that will depend on the local evolution of the limb and the overall development of each patient, guided by different predictive and prognostic scales.14

In this group of traumas we also include inguinal-perineal injuries, which occupy second place in frequency of involvement together with abdominal traumas (11%), after accidents that occur during popular celebrations.

Inguinal wounds have a high percentage of vascular and even visceral involvement, which require urgent and rapid management, so they should be considered an emergency. In addition to assessment by general surgery, they should be assessed by vascular surgery.

These are high morbidity injuries, which can also affect intra-abdominal structures and large retroperitoneal vessels, and therefore cause hypovolemic shock. This is the main reason why this type of injury must be assessed in by a vital signs monitor in the UAIT, following the ATLS guidelines.

Peripheral vascular trauma (Fig. 6)Vascular trauma is one of the most frequent and serious injuries that occur in bullfighting. Penetrating vascular trauma often threatens the patient's life immediately. The most frequent locations are the ilio-femoral and femoro-popliteal sectors.

In the case of a life-threatening vascular injury, the most appropriate care protocol would be X-ABCDE, treating the exsanguinating haemorrhage immediately.15 This type of injury must therefore be urgently assessed by general surgery and vascular surgery.

The first way to contain the haemorrhage is direct compression at the site of the wound with the fist or the palm of the hand covered with compresses. If the bleeding persists, the next step will be to apply a pressure bandage with compresses or a circumferential elastic bandage, considering pressure in the area proximal to the injury. Finally, if the bleeding continues, consider placing a manual or pneumatic tourniquet proximal to the injury.

DocumentationThe data registration, primary assessment and hospital care sheets included in the clinical guidelines for the management of severely polytraumatised adult patients will be completed.

Furthermore, the medical report must concisely detail the wound location, directions and trajectories, as well as the location of the drains.

In the medical report injury prognosis is given based on the expected healing time of the wounds. The injury prognosis will be:

- •

MILD: foreseeable healing time under 15 days.

- •

MODERATE: foreseeable healing time between 15 and 30 days.

- •

SEVERE: foreseeable healing time over 30 days. By definition, gorings affecting the muscular aponeurosis, are always of serious prognosis.

We would underline the importance of injuries caused by bullfighting trauma worldwide, especially in Spain and some Latin American countries, where bullfighting events are commonplace.

It is essential to establish strategies for the comprehensive care of patients injured by bullfighting trauma that serve as a reference, since these are high-impact injuries with specific intrinsic characteristics that require regulated medical–surgical care and assistance, in polytraumatised patients, with a not inconsiderable morbidity and mortality.

This review is therefore not only aimed at expert bullfighting surgeons, but also at all health professionals (surgeons, traumatologists, emergency physicians, general physicians, intensivists, anaesthetists, nurses, out-of-hospital health personnel) who may be involved in the care process of these patients.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

AuthorshipAndreu Martínez conceived and designed the manuscript, and also wrote it. Génesis Jara performed data analysis and interpretation. Celia Roig and Carlos Ordóñez participated in the writing of the manuscript. José Manuel Laguna reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Ethical responsibilitiesAll authors have confirmed the maintenance of confidentiality and respect for the rights of patients in the author's responsibilities document.

FundingThe authors declare that there was no funding in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare in relation to this article.

We would like to thank all the healthcare members of the Castellón Health Department for their collaboration.