Lateral epicondylitis is a common injury in the population. Most patients improve with conservative treatment, but in a small percentage surgery is necessary. The aim of this study is to analyse the clinical results obtained by a “4 surgical tips” technique.

Materials and methodThis is a retrospective study of 35 operated elbows, with a mean follow-up of 5.3 years. In all cases epicondylar denervation, removal of the angiofibroblastic degeneration core, epicondylectomy, and release of posterior interosseous nerve, was performed. Each patient was evaluated using the Broberg and Morrey Rating System (BMRS), Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), DASH questionnaire, and a survey of subjective assessment.

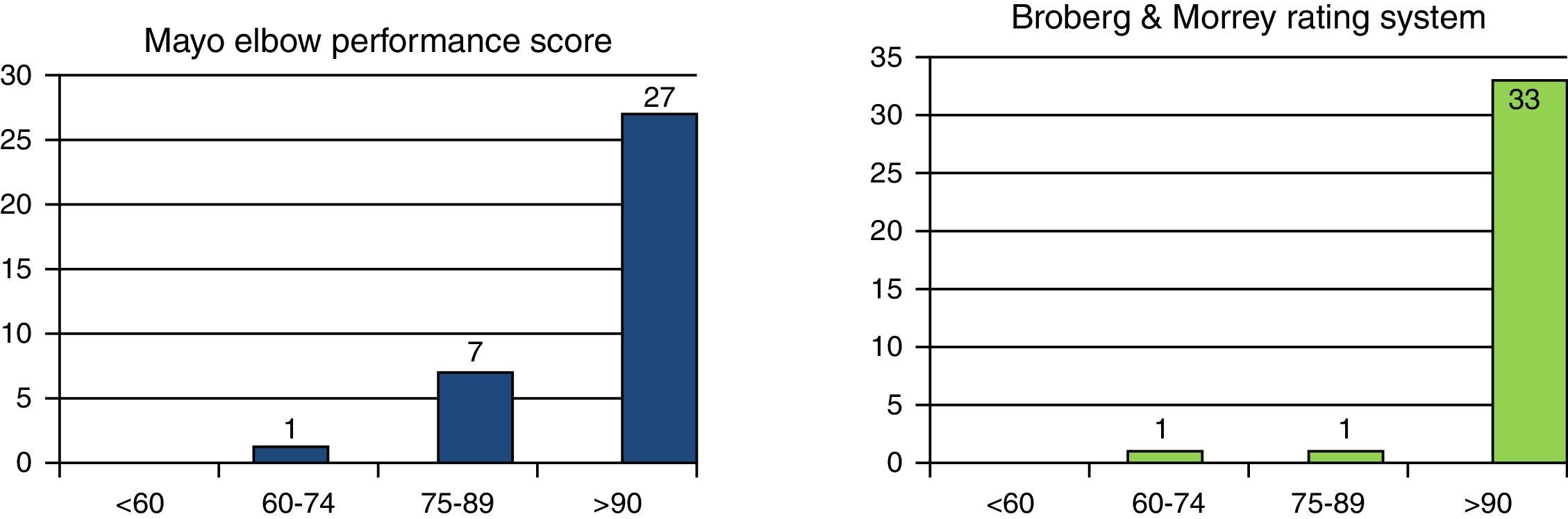

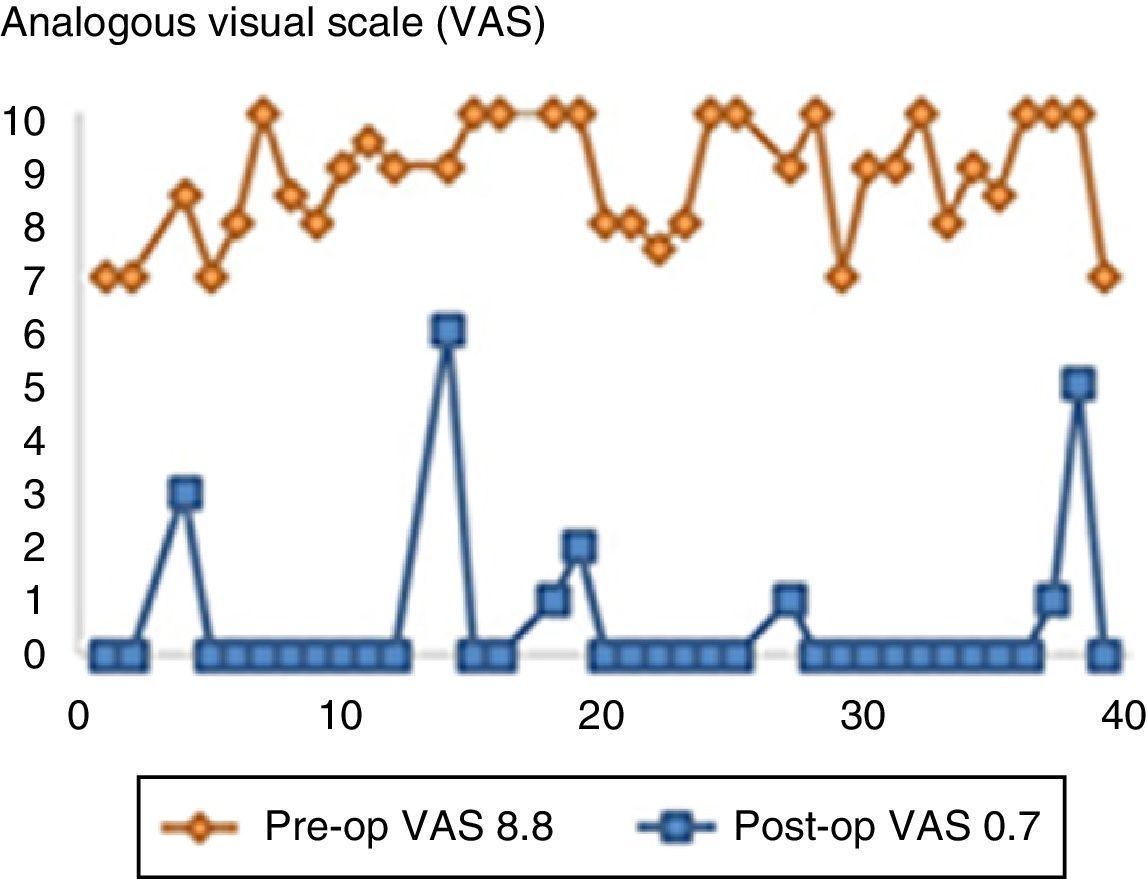

ResultsBMRS mean score was 97.2 points, with 95.71 points with the MEPS. The mean decrease in VAS was 8.12 points, and the mean score on the DASH was 1.68 points. The results were rated as excellent or very good by 94.3% of patients. There was one recurrence, which resolved with further surgery. Two neuropraxia of the posterior interosseous nerve occurred, which completely recovered in 10 weeks.

ConclusionsUsing the “4 surgical tips” technique, clinical resolution of symptoms in 97.1% was achieved at the first operation. Therefore, it appears to be an effective, reproducible technique with few complications, in the surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis resistant to conservative treatment.

La epicondilitis es una lesión muy frecuente en la población. La mayoría de los pacientes mejoran con el tratamiento conservador, pero en un pequeño porcentaje será necesaria la cirugía. Nuestro objetivo es analizar los resultados clínicos obtenidos mediante una intervención consistente en «4 gestos quirúrgicos».

Material y métodoEstudio retrospectivo de 35 codos intervenidos con un seguimiento medio de 5,3 años. En todos los casos se realizó denervación epicondílea, extirpación del núcleo de degeneración angiofibroblástica, epicondilectomía y liberación del nervio interóseo posterior. Se recogieron los resultados mediante Broberg and Morrey Rating System (BMRS), Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS), Escala Visual Analógica (EVA), cuestionario DASH y una encuesta de valoración subjetiva por parte del paciente.

ResultadosLa puntuación media del BMRS fue de 97,2 puntos, MEPS de 95,71 puntos. La reducción media en la EVA fue de 8,12 puntos y la puntuación media en el DASH fue de 1,68 puntos. El 94,3% de los pacientes valoraron el resultado como excelente o muy bueno. Se produjo una recidiva que se solventó con una nueva cirugía y una neuroapraxia del nervio interóseo posterior en 2 casos, recuperados íntegramente en 10 semanas.

ConclusionesCon esta intervención basada en 4 gestos, se ha conseguido la resolución clínica en el 97,1% de los casos en la primera cirugía, por ello, consideramos esta técnica efectiva, reproducible y con una aceptable tasa de complicaciones en el tratamiento quirúrgico de la epicondilitis resistente a tratamiento conservador.

Epicondylitis is an injury commonly diagnosed by orthopaedic surgeons. It has been estimated that between 1% and 3% of the population will present with it per year1 with no differences between genders and with usual occurrence between 35 and 50 years of age.2 Of these patients, approximately half will require some type of medical attention.3

The majority of patients will improve with conservative treatment,1,4 or even with no treatment, within 6–12 months5 while up to 5% of patient will eventually require surgical treatment.1

Standard surgical procedures in epicondylitis treatment can be divided into 6 groups: division of the common origin of the extensors, removal of the angiofibroblastic degeneration core in the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), epicondylar denervation, epicondylectomy, release of posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) and lastly different intra-articular procedures.1,6 Arthroscopic debridement was added as a procedure from 2000 onwards.7 It is our understanding that this classification is currently insufficient in medical practice given that the majority of authors associate different surgical tips with their techniques.1,6,8

The aim of our study was to analyse the clinical results obtained through a surgical intervention based on the association of “4 surgical tips”.

Material and methodWe carried out a retrospective study of 35 elbows in 31 patients who underwent surgery in our epicondylitis centre between October 2004 and October 2012 and who were resistant to conservative treatment. Clinical records were reviewed and patients were given an appointment to determine their current clinical status.

Diagnosis of epicondylitis was clinical, patients presenting with pain in the lateral epicondyle spreading to the forearm, epicondyle pain with forced extension of the wrist or fingers when the elbow was extended, pain in the region of the lateral epicondyle during resisted extension of the middle finger keeping the forearm in supination (positive Maudsley's test).9 A plain anteroposterior and lateral X-ray of the elbow was indicated for all patients to rule out intra-articular injuries which could have altered the surgical technique to be applied.

We defined conservative-treatment-resistant epicondylitis as epicondylitis with no clinical improvement after at least 6 months of conservative treatment and we indicated complete surgical technique including the 4 tips, in those patients who had not improved after 6 months of medical treatment and who also presented discomfort in their forearm referred to as “a feeling of stiffness” or undefined pains which spread to the forearm.

Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of epicondylitis with a duration of symptoms for at least 6 months, non-response to conservative treatment for at least 6 months, including anti-inflammatory therapy, armband, physiotherapy, and the presence of other forearm symptoms which prevented any clear differentiation between epicondylitis and radial tunnel syndrome.

Of the 31 patients, 22 were male and 9 female. Four of the men and none of the women had been operated on both elbows. The mean age at time of surgery was 46 (25–66) and mean follow up was 5.3 (1.5–10.6) years. In 23 cases the right side was operated on and the left in the remaining 12 cases. The dominant arm was operated on in 54.2% of the elbows.

Our patients were classified according to the physical intensity of the work they had previous been doing, considered as heavy (construction, fishing, agriculture) in 43% of cases, moderate (catering, driving) in 40% and light (teaching, administrative) in the other 17% of cases.

All patients had received treatment with non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prior to surgery and all of them had used different types of armband orthoses. In 29 of the 35 elbows, at least one infiltration (mean: 1.2 infiltrations) were performed with a local anaesthetic and corticoidsteroids. In 5 of the remaining 6 patients, infiltration was not performed due to medical contraindication and the sixth patient rejected infiltration.

Moreover, in 19 out of 35 elbows physiotherapeutic treatment was administered for a mean of 5.3 weeks, with no improvement.

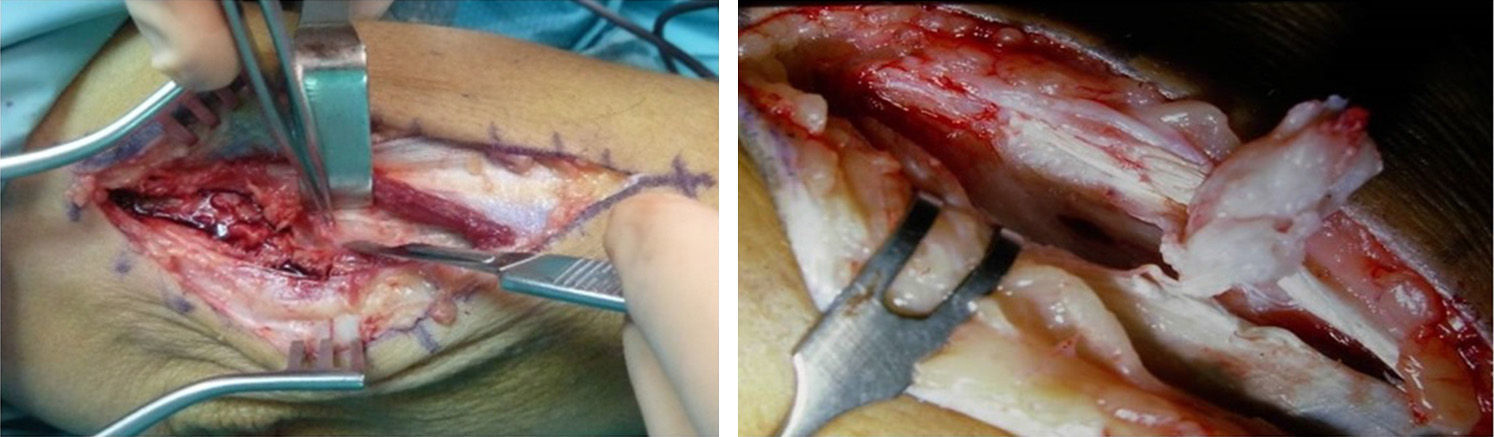

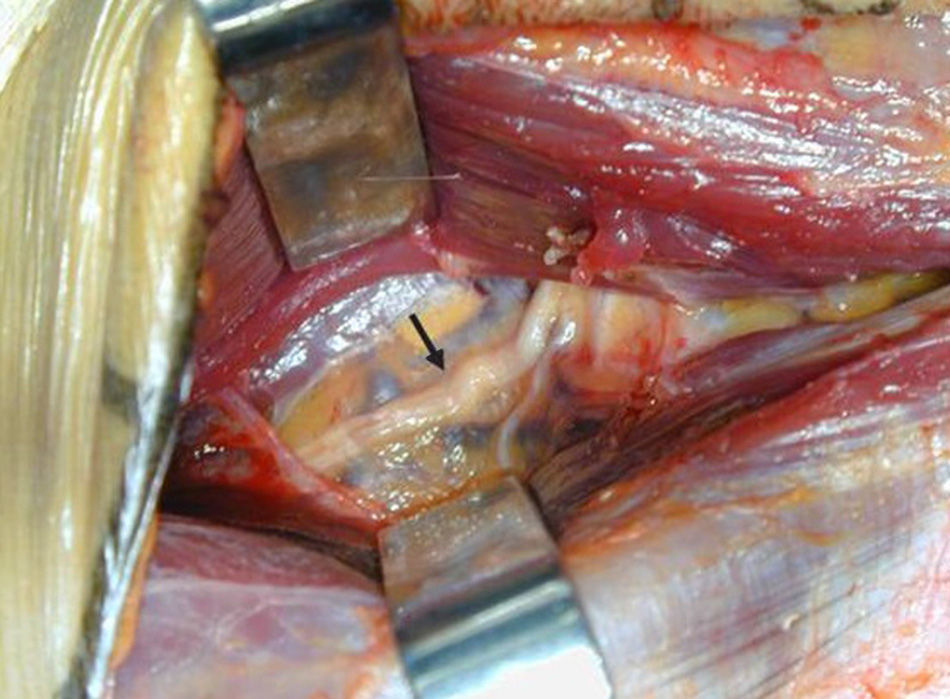

All the patients underwent surgery in the outpatient unit and under local regional anaesthesia (brachial plexus). The patient was positioned in a supine position and with the affected arm on a hand surgery table. A preventive ischaemia tourniquet was used at the arm site and magnifying glasses were used. An italic S incision was made, centred in the epicondyle, extending along 1.5cm proximal length and drawing a posterior concavity curve to the distal edge (Fig. 1). Initially, we performed denervation of the lateral humeral epicondyle with a bipolar electric scalpel and sectioned the sensitive epicondylar branches described by Wilhelm (branches from the radial nerve which emerge proximal to the radial tunnel and lead to sensory innervation of the lateral epicondyle).9,10 We located the ECRB and sectioned it lengthwise to resection the Nirschl angiofibroblastic degeneration nodule2 usually located at a profound and anterior level, through the distal finger to the epicondyle (Fig. 2). We performed a discreet epicondylectomy, or decortication of the epicondyle with a gauge needle. We finally released the PIN at the level of the 4 most common compression areas, the recurrent radial blood vessels, the aponeurosis proximal to ECRB, the arcade of Fröhse and the distal edge of the supinator (Fig. 3). We closed the ECRB incision on the nodule and sutured the flesh with dissolvable 4/0 braided sutures. The arm was kept in a sling for 7 days.

Data was collected using the post-operative Broberg and Morrey Rating System (BMRS),11 the post-operative Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS),12 the time elapsing before resuming employment and sports activities after surgery, the pre-operative Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and after follow-up, the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH)13 post-operative questionnaire was used with a closed question where each patient had to classify the result of surgery as excellent, very good, good, OK or bad. No pre-operative BMRS, MEPS or DASH results were available.

ResultsThe pre-operative plain X-ray image showed a lateral calcification at epicondyle tendon insertion level in 4 of the 35 elbows, 11.4%.

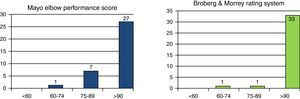

The mean post-operative score in the BMRS was 94.7 (71–100) points with a standard deviation of 8.67 and confidence interval of 95% (90.5–96.3); 94.3% of our cases rated surgery as excellent. We obtained a score of 95.7 (60–100) points in the MEPS with a standard deviation of 6.2 and a CI of 95% (92.7–96.7); 97.1% of our cases rated surgery as excellent or good (Fig. 4).

The mean time elapsing before going back to work, in those patients who had not been nor became unemployed (this occurred in 5 out of the 35 cases) was 7 (2–12) weeks. The mean time elapsing before reinitiating sports activities was 10 (6–20) weeks in those patients who practised some type of sport which affected their elbow which had been operated on (6 out of 35 patients).

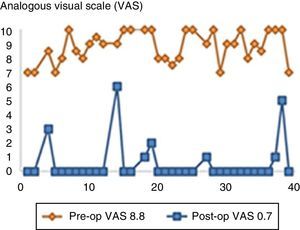

The mean score in preoperative VAS measured during the activity of the affected arm was 8.8 (7–10) points with a standard deviation of 1.08 and a CI of 95% (8.24–8.96). The average score in the post-operative VAS measured during activity was 0.7 (0–6) points with a standard deviation of 1.59 and a CI of 95% (0.18–1.24), obtaining a mean reduction of 8.1 (3–10) points (Fig. 5). Statistical analysis of the pre- and post-operative VAS results was made using the t-Student test for comparison of means for unpaired data, with a statistically significant difference of P<0.00.

Mean post-operative score in the DASH questionnaire was 1.7 (0–20.4) points with a standard deviation of 1.58 and CI of 95% (0.18–1.24), with the outcome being considered as excellent in 33 of the 35 elbows operated on.

Lastly, with reference to patient assessment, 71.4% considered the procedure excellent, 22.9% as very good and the other 5.7% as good.

There was one recurrence which was diagnosed 23 months after surgery and was resolved with a further debridement of the ECRB origin and epicondyl denervation, performed 28 months after initial surgery. Two neuropraxia of the PIN occurred which completely recovered with conservative treatment within a period of 10 weeks after surgery.

DiscussionTreatment objectives for “tennis elbow” include: pain management, preservation of movement, improvement of grip strength and a return to any working and sports activities without limitations.8 Many treatments are available, the majority of which have been endorsed by scientific literature.

Conservative treatment described by Cyriax5 has been used and includes physiotherapy, stretching, compression armbands, iontophoresis, shock-wave therapy, laser therapy, acupuncture, topical anti-inflammatory treatments and infiltrations with different substances.5,8,9 Despite the many diverse therapeutic options, approximately 5% of patients will require surgical treatment.1

Many surgical techniques have been described for the treatment of resistant epicondylitis. The surgeon is faced with many treatment options but without a profound understanding of the mechanisms through which successful outcome may be achieved.8

Variable outcomes between 69% and 100%,9 are achieved with the open release of the extensor muscle origin, but when this is performed in patients who have been receiving at least 6 months of conservative treatment, it appears that only 40% of them are symptom-free one year after surgery.14 This figure rises to 75% if there is decortication of the lateral epicondyle.15

According to published studies in 90% of cases cessation of symptoms is achieved with percutaneous release. The main advantage is early return to work, but there is increased risk of synovial cysts and infection.9,16,17

If ECRB debridement is associated with open release, the removal of degenerative tissue and epicondyl decortication, as documented by Nirschl and Pettrone, clinical resolution of symptoms in 84%–97% of patients is achieved.18,19

Good or excellent results are obtained in 85%–91% of cases20,21 with denervation of the lateral humeral epicondyle, whether associated with tenotomy of supination origin or not.

Furthermore, the contribution of PIN compression after clinical diagnosis has been widely debated in literature. The incidence of radial tunnel syndrome or isolated supinator syndrome has been estimated to present in 2% of peripheral nerve entrapment of the upper arm.22 On occasions, it is not easy to clinically distinguish epicondylitis from radial tunnel syndrome and both conditions frequently present simultaneously.9,23 We consider that the electromiography is not useful in differential diagnosis since nerve compression is dynamic and also, despite the availability of a dynamic electomiograph, the latter results in a false negative in up to 15% of cases.6,24,25 Infiltration with a local anaesthesia at epicondyle level or in the radial tunnel has also been suggested for reaching differential diagnosis.6,26 We consider this method non reproducible since we cannot be sure that the anaesthesia would not diffuse from one location to another and therefore distort the outcomes. In literature, with isolated release of the PIN and removal of the ECRB origin similar outcomes are obtained.27,28

Lastly, another surgical option is arthroscopic treatment, initially described by Grifka et al. in 199529 with satisfactory results published in 87%–93% of cases.30,31 The main advantage of this option is the possibility of articular examination and an earlier return to work.9,32 Among its disadvantages are longer surgery, the possibility of radial nerve injury8,33 and the impossibility of releasing the PIN.

The only series described in literature in which reference is made to the technique we have used, including the 4 surgical tips, was published by Foucher in 1996.6 He presents a total of 42 patients who were operated on but only in 24 of them is the complete technique used, with good or excellent results in 88% of his patients with a 72% reduction in VAS.

In our series we obtained the complete resolution of symptoms (post-operative VAS of 0 points) in 80% of cases (28 out of 35). We obtained a good result (reduction of over 50% of VAS score but without a post-operative VAS of 0 points) in 14% of cases (5 out of 35). Partial improvement was achieved in the remaining 6% (2 cases) where we achieved a reduction in the VAS score of 41.6%.

Surgery was indicated at least 6 months after conservative treatment similarly to cases documented in literature.8,9 A recent study has been published which analyses the cost effectiveness of surgery and concludes that after 3 months of conservative treatment a plateau stage is reached where the rate of patients who improve stabilises but the costs derived from the condition continue to rise. An optimum time for surgical treatment is therefore proposed, 3 months after the start of medical treatment.34 This study requires new research, but could change our normal treatment guidelines.

There are a number of limitations to our study including retrospective design and a small sample size, although since indication for complete surgery is strictly selective, it is difficult for us to obtain a much larger sample size.

Despite the large number of published works, debate continues regarding the exact aetiology of epicondylitis and the best method of treating it, with no one technique demonstrating a clear superiority over any other. In cases where there is resistance to conservative treatment and mainly when the patient presents with a badly defined clinical picture where we suspect the presence of a epicondylitis, but concomitant radial tunnel syndrome cannot be ruled out, we believe that this association of several procedures is the best way of trying to ensure a good clinical outcome. For this reason in our Hand, Upper Limb and Peripheral Nerve Unit the frequency with which we indicate the complete technique has evolved from being occasional to being a not inconsiderable number of cases (provided they meet the indication criteria), possibly up to 20% of surgically treated epicondylalgias, with favourable outcomes that reflect our efforts.

We believe this study shows that in the treatment of epicondylitis which is resistant to conservative treatment, this technique based on 4 surgical tips is effective, reproducible, offers good functional results, and reduces the VAS score significantly at the cost of an acceptable rate of complications.

Our results are certainly satisfactory, but we must remember that surgical treatment is not the panacea and therefore continues to falter whilst we are as yet unaware of the detailed pathophysiological mechanism of the lesion.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that for this research no experiments using humans or animals were performed.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre regarding patient data publication.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez I, Marcos-García A, Muratore-Moreno G, Medina J. Cuatro gestos quirúrgicos en el tratamiento de la epicondilitis. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;60:38–43.