There are different techniques and interpretations of discography findings to determine it positive for the diagnosis of discogenic pain. This study aims to evaluate the frequency of use of discography findings for the diagnosis of low back pain of discogenic origin.

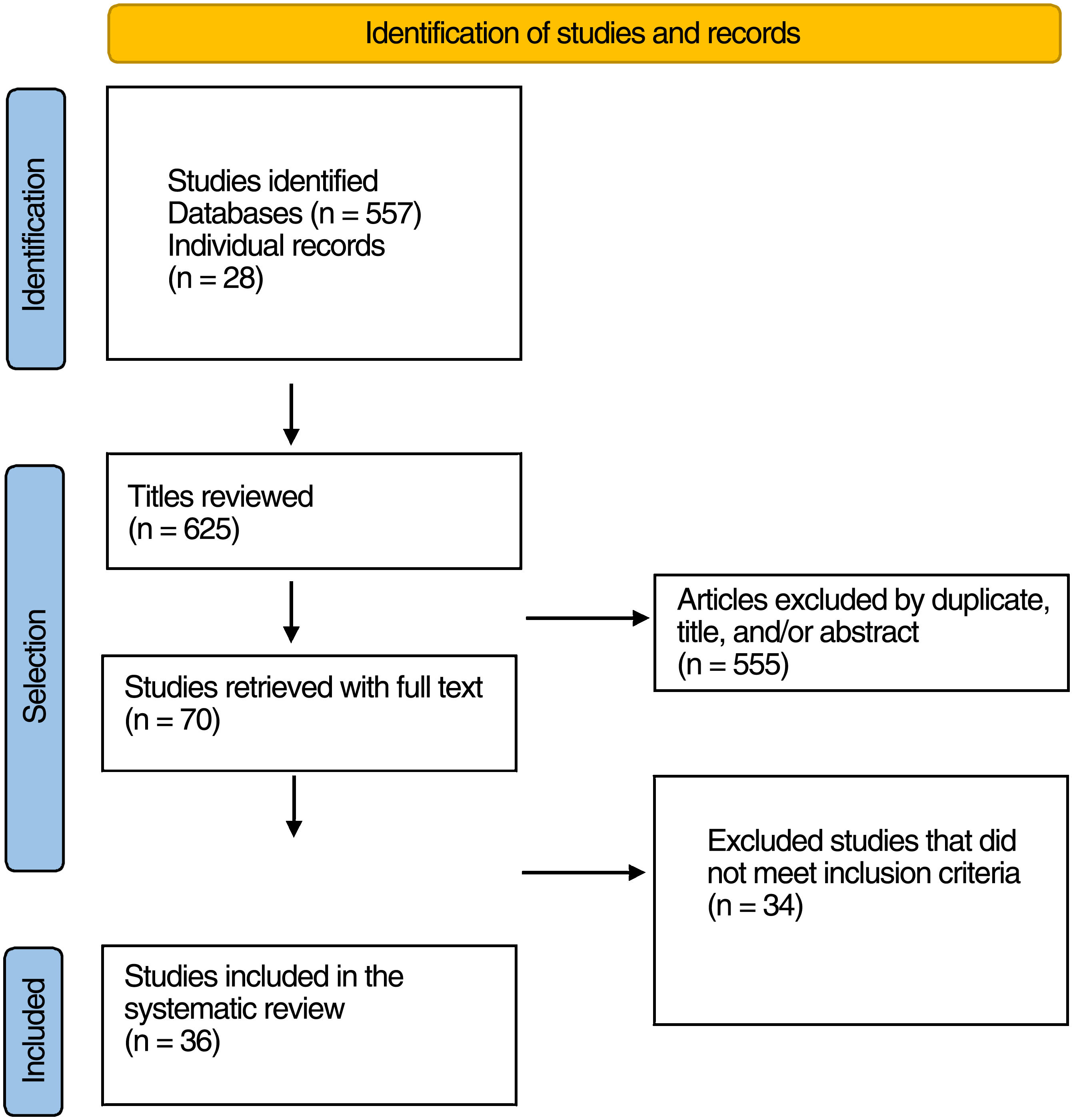

Material and methodsA systematic review of the literature of the last 17 years was performed in MEDLINE and BIREME. A total of 625 articles were identified, 555 were excluded for duplicates, title and abstract. We obtained 70 full texts of which 36 were included in the analysis after excluding 34 for not meeting the inclusion criteria.

ResultsAmong the criteria in discography to determine it as positive, 8 studies used only the pain response to the procedure, 28 studies used more than one criterion during discography to consider it as positive, the evaluation of at least one adjacent intervertebral disc with a negative result was necessary in 26 studies to consider a discography as positive. Five studies formally expressed the use of the technique described by SIS/IASP to determine a discography as positive.

ConclusionsPain in response to contrast medium injection, assessed with the visual analogue pain scale ≥6, was the most used criterion in the studies included in this review. Although there are already criteria to determine a discography as positive, the use of different techniques and interpretations of discography findings to determine a positive discography for low back pain of discogenic origin persists.

Existen diferentes técnicas e interpretaciones de los hallazgos en la discografía para determinarla positiva para el diagnóstico de dolor discogénico. Este estudio pretende evaluar la frecuencia de uso de los hallazgos de la discografía para el diagnóstico de la lumbalgia de origen discogénico.

Material y métodosSe realizó una búsqueda sistemática de la literatura de los últimos 17años en MEDLINE y BIREME. Se identificaron en total 625 artículos, de los que 555 fueron excluidos por duplicados, título y resumen. Se obtuvieron 70 textos completos, de los que 36 se incluyeron en el análisis tras excluir 34 por no cumplir los criterios de inclusión.

ResultadosEntre los criterios en la discografía para determinarla como positiva, 8 estudios utilizaron únicamente la respuesta del dolor al procedimiento y 28 estudios utilizaron más de un criterio durante la discografía para considerarla positiva: La evaluación de al menos un disco intervertebral adyacente de resultado negativo fue necesaria en 26 estudios para considerar una discografía como positiva. Cinco estudios expresaron formalmente el uso de la técnica descrita por la SIS/IASP para determinar una discografía como positiva.

ConclusionesEl dolor en respuesta a la inyección de medio de contraste, evaluado con la escala analógica visual de dolor ≥6, fue el criterio más utilizado en los estudios incluidos en esta revisión. Aunque ya existen criterios para determinar una discografía como positiva, persiste el uso de diferentes técnicas e interpretaciones de los hallazgos de la discografía para determinar una discografía positiva para el dolor lumbar de origen discogénico.

Low back pain of discogenic origin has been studied for almost half a century. Mixter and Barr made the first descriptions of intervertebral disc rupture in 1934. Intervertebral imaging findings have been linked to discogenic low back pain. Patterns of rupture of the annulus fibrosus as seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or discography have been described.1 Likewise, Peng et al. describe that high intensity areas in the intervertebral disc evidenced on MRI can be correlated as a reliable marker of painful annulus fibrosus rupture. However, this finding has also been described in asymptomatic individuals.2

Chronic low back pain shows a linear increase from the third decade of life onwards, being more prevalent in women up to the age of 60 years. The prevalence of low back pain varies by age group: 4.2% in individuals aged 24–39 years, 23.3% in individuals aged 25–74 years, and 25% in adults over 60 years.3

Facet joints, sacroiliac joints, and the intervertebral disc are sources of spinal pain in 70%.4 Discogenic low back pain is characterised as axial pain, where radiologically there is no herniation, spinal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, or any other condition. Its pathophysiology is complex and not fully understood; however, it is known that there are mechanical loads in certain areas of pre-existing degeneration and rupture of the annulus fibrosus that can lead to sensitisation of the annular nociceptors. Thus, mechanical, and neural factors contribute to disc-mediated pain, explaining the importance of increased intradiscal pressure and the rate at which this pressure increases on discography that would stimulate nociceptors in the outer third of the disc.5,6

Clinical history, physical examination, and radiological imaging used for diagnosis have reported low sensitivity and specificity to determine, on its own, whether the source of pain is discogenic.7 In 2020, a mapping review of the literature found the most commonly reported signs and symptoms in the diagnosis of discogenic low back pain, with stand in two phases and poor response to facet and sacroiliac block being the two most frequently used clinical signs.8 There are many management guidelines that propose different techniques to assess the origin of low back pain.9

Discography is performed by injecting radiographic contrast into the nucleus of an intervertebral disc. Pain at the time of injection is assessed in terms of location and similarity to clinical symptoms. It is the only diagnostic technique that correlates the radiological image with the patient's pain.10,11 It allows evaluation of the volumetric capacity of the disc, manometry parameters, radiological image characteristics, and response to the provocation test, and therefore multiple variables must be analysed for a discogram to be assessed as positive.

In 2013, the Spine Intervention Society (SIS) proposed diagnostic criteria for determining a positive discogram for discogenic low back pain. These include pain concordant or ≥6 with contrast injection at a specific volume and pressure, evaluating at least one disc adjacent to the level of interest.12 However, different techniques and determinants are still used to consider a discogram positive.

Given the inconsistencies in the different results found with respect to lumbar discography, the aim of this study is to present a systematic review of the literature to evaluate the frequency of discographic findings for the diagnosis of discogenic low back pain.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a systematic search of the literature from the last 17 years in MEDLINE and BIREME using the following search terms:

- -

(dolor lumbar[MeSH terms]) AND discografía[MeSH terms].

- -

Low back pain AND discography AND (type_of_study: (“clinical_trials” OR “systematic_reviews” OR “guideline”) AND: (“en” OR “es”)) AND (year_cluster: [2005 TO 2022]).

A total of 625 articles were found. Studies in English or Spanish were reviewed that aimed to diagnose low back pain of discogenic origin, that used discography as the sole or as an adjunctive method for its diagnosis, that also described the technique for performing discography and the criteria for determining a discography as positive for discogenic low back pain, and published between January 1, 2005 and April 30, 2022. Cadaveric studies, non-human studies, case reports, technical notes, literature reviews, notes to the Editor, and descriptive studies were excluded.

Articles were initially analysed by title and abstract. The full texts of relevant articles were obtained, and their references were scanned to identify other studies of interest and analysed. The following data were extracted from all articles: study objective, conclusion of the study, criteria for performing discography, total number of patients in the study, number of patients undergoing discography, total number of intervertebral discs operated, levels of intervertebral discs operated, criteria for determining discography as positive, criteria for determining discography as negative, criteria assessed during discography, total number of positive discs per discography, and total number of negative discs per discography.

Assessment of the quality of the articlesTwo researchers independently used the Spanish version of the Quality Assessment Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool to assess the quality of the articles included in the review.13

ResultsA total of 625 articles were identified (Fig. 1), from which we excluded duplicates, title, and/or non-relevant abstracts. Seventy full texts were obtained; 36 were included in the analysis after excluding 34 because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Tables 1 and 2 summarise the studies included in the review.2,6,7,11,14–45 The quality of the studies was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool, which is presented in Table 3 and summarised in Figs. 2 and 3. In assessing the risk of bias of the studies and concerns for applicability, patient selection in the different studies was found to present the highest risk of bias of the 4 items assessed in the tool (patient selection, index test, reference standard, flow, and time). The significant proportion of retrospective studies included in the systematic review and the sample of case-control studies explain this higher risk of bias. Concerns about the applicability of the studies to the systematic review are low, as the condition of discogenic low back pain diagnosed by the reference test does not differ from the population addressed by the research question of this systematic review (Table 3).

Objective and outcome of the articles.

| Study | Result | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Jain et al.,18 2021 | They recommend the use of MRI as a screening tool for chronic low back pain due to the characteristics that can be seen on the image indicative of discogenic pain. Disc desiccation is the most useful | To identify the correlation between MRI findings and discography result in diagnosing discogenic pain. |

| Son et al.,14 2021 | The disc height discrepancy ratio between supine and standing could be a screening metric for discogenic low back pain in early to middle stage disc degeneration of the lumbar spine. | To investigate disc height (DH) discrepancy between supine and standing positions on simple radiography to clarify its clinical screening value in individuals with discogenic low back pain |

| Torén et al.,15 2020 | The spinal loading-effect, depicted with MRI, reveals different regional behaviours between IVDs with outer fissures compared to those without, and between IVDs with narrow and broad fissures, between pain-positive and pain-negative discograms. | To investigate whether spinal loading, depicted with MRI imaging, induces regional intervertebral disc differences associated with presence and width of annular fissure and induced pain at discography. |

| McCormick et al.,19 2019 | Patients with symptomatic low back pain who underwent low-pressure discogram, but who did not undergo a subsequent spinal fusion surgery, developed disc degeneration and new disc herniations at a similar rate to corresponding discs in matched control patients. | To determine if low-pressure lumbar provocation discography results in long-term accelerated disc degeneration, internal disc disruption, or disc herniation in patients with symptomatic low back pain. |

| Chelala et al.,20 2019 | Disc herniations and HIZ discs have high predictive value in identifying a discogenic low back pain generator. | To calculate the positive predictive value of lumbar spine MRI for a painful disc using provocative discography. |

| Wang et al.21, 2017 | The presence of HIZ on MRI is only a suggestive finding of discogenic low back pain, however, it cannot replace the gold standard of discography. | To analyse the correlation between high-intensity zone on MRI of an IVD and positive pain response assessed by discography for the diagnosis and treatment of discogenic low back pain |

| Liu et al.,22 2018 | Painful Schmorl's nodes refractory to medical or physical therapy should be an indication for treatment with discography and discoblock. | To determine the efficacy of discography and discoblock in the treatment of LBP associated with painful Schmorl's nodes. |

| Kallewaard et al.16, 2018 | Pressure rise in adjacent discs does not seem to occur during low-speed flow pressure-controlled lumbar provocation discography. False-positive pain reactions caused by potentially painful adjacent discs are therefore unlikely during pressure-controlled discography. | To determine whether there is pressure rise in adjacent discs affecting the rate of true positives in flow pressure-controlled discography. |

| Lee et al.,23 2017 | Automated pressure-controlled provocation discography can identify discogenic back pain by automatically recording the intradiscal pressure, injected volume, and pain response, thereby improving accuracy and objectivity. | To evaluate APCD as a diagnostic tool for discogenic low back pain in patients undergoing anterior interbody fusion. |

| Xi et al.,24 2016 | Lumbar discography with post-discography CT can be an effective method to evaluate patients with discogenic back pain refractory to non-operative treatments. Patients with one- or two-level high concordant pain scores with associated annular tears and negative control disc are surgical candidates for lumbar interbody spinal fusion. | To explore the relationship between discogenic pain and disc morphology using discography and CT, respectively, and investigate the efficacy of this combined method in identifying surgical candidates for lumbar fusion. |

| Verrills et al.,25 2015 | The prevalence of discogenic pain in this community practice is below the range, but within confidence intervals. However, among well-selected patients, prevalence is considerably elevated. Discography enabled a firm diagnosis in most such cases. | To assess the prevalence and key features of discogenic pain in practice. And to evaluate the accuracy and clinical utility of discography. |

| Kim et al.,26 2015 | There was a higher correlation between general degeneration and age, as compared with annular disruption and age. Higher general degeneration and annular disruption grades had higher positive rates of discography. However, annular disruption alone was independently associated with positive discography. Age and grade of general degeneration did not affect the prognosis. | To investigate the correlation among age, disc morphology, positive discography, and prognosis in patients with chronic low back pain. |

| Hebelka et al.,27 2014 | Changes in the morphological appearance occurred in at least one disc level in all patients when loaded and unloaded MRI were compared. There were no significant differences between concordant and discordant discograms in terms of morphological disc features at conventional MRI. | To evaluate the influence of dynamic MRI in relation to provoked pain at discography. |

| Bartynski et al.,28 2013 | CLBP was more frequent in women with other CLPB-associated lesions compared to men. In the general population there were no significant differences in the features at painful concordant discs. | To compare the “precipitating” events or “causes” of chronic low back pain with the disc features identified at CT, at the concordant painful disc levels for a provocative lumbar discography |

| Putzier et al.,29 2013 | They suggest discoblock as an additional tool for surgical decision-making in patients with idiopathic degenerated discs. They conclude that it correlates to concordant pain evoked by provocative discography as well as to the presence of Modic changes on MRI. | To evaluate the influence of dynamic MRI in relation to provoked pain on discography. And to intra-individually compare provocative discography and discoblock of IDD to clinical parameters and to MRI findings |

| Hebelka y Hansson,30 2013 | Axial loaded MRI did not affect the detection of HIZ compared with conventional MRI. No significant correlation between HIZ and pain response at discography was found. | To investigate if the detection of HIZ is affected by axial load, and to study the correlation between HIZ and discogenic pain provoked with pressure-controlled discography. |

| Berg et al.,31 2012 | In subgroups of patients with CLBP that could be caused by degenerative disc disease, carefully selected by a certain group of spine surgeons, provocative discography had a great impact in the decision-making process and frequently altered prediscography decisions. It is unknown whether the patient's outcome improved, worsened, or was unaffected by the interpretation. | To highlight how discography affects surgical decisions when performed on one of 4 different indications in a complicated subgroup of patients with low back pain assumed to be associated with degenerative disc disease. |

| Bartynski and Rothfus,32 2012 | In patients with CLBP peripheral disc margin shape correlates with features of disc internal derangement in significantly painful discs identified at provocation lumbar discography. Disc protrusion is seen in the presence of underlying radial defect (radial tear, annular gap) with thin overlying peripheral annular margin. Disc bulge suggests the presence of complex disc degeneration with annular fragmentation. | To compare peripheral disc margin shape with internal disc derangement in painful discs identified at provocation lumbar discography. |

| Derby et al.,33 2011 | Equivalent positive discogram rates were found following a series of pressure-controlled discography using either an automated or manual pressure device. However, there were significant increases in volume at both initial onset of evoked pain and at 6/10 pain when using the automated injection device that may have caused the observed lower opening pressure and lower pressure values at initial evoked pain. | To compare the rate of positive discograms using an automated versus a manual pressure-controlled injection device. Pressure and volume values were compared at various pressures and initial evoked pain and 6/10 or greater evoked pain. |

| Chen et al.,34 2011 | Disc degeneration grades on MRI showed an association with discographic grades. Type IV–V discs on discography, Grade IV–V disc on MR images, the presence of HIZ and endplate abnormalities might indicate discogenic pain in patients with CLBP. | The objective of this study was to correlate MRI findings and discography with pain response at provocative discography in patients with low back pain. |

| Alamin et al.,35 2011 | The findings of the test differed from those of standard pressure-controlled provocative discography in 46% of the cases reported. Further studies will be needed to demonstrate the clinical utility of the test. | To compare the results of standard pressure-controlled provocative discography to those of the functional anaesthetic discogram in a series of patients presenting with CLBP and considering surgical treatment. |

| Derby et al.,36 2010 | Using equal mixtures of injected local anaesthetic and contrast during provocative discography did not provide significant overall subjective pain relief compared to using contrast alone in a comparative separate cohort. | To confirm that injecting local anaesthetic in intervertebral discs would provide convincing pain relief and that the degree of pain relief would help confirm or refute the findings of provocative discography. |

| Zhang et al.,37 2009 | 1. Compared with the younger patients, older low back pain patients have a lower positive rate of discography.2. Outer layer disruption of the annulus fibrosus correlates with positive discography.3. MRI intensity changes are not specific in diagnosing discogenic pain. Additional discography is needed to identify the painful disc.4. The contrast volume injected into discs can be affected by a variety of factors with restrict its diagnostic value. | To evaluate the diagnostic effectiveness of discography in discogenic low back pain. |

| Thompson et al.,38 2009 | Type 1 Modic changes on MR images have a high positive predictive value in the identification of a pain generator. | To assess the value of Modic changes on MR images in predicting a painful disc, with provocative discography as the reference standard |

| Ohtori et al.,39 2009 | Pain relief after injection of a small amount of bupivacaine into the painful disc was a useful tool for the diagnosis of discogenic low back pain compared with discography. | To evaluate the diagnosis of discogenic low back pain with discography and discoblock. |

| O’Neill et al.,40 2008 | MRI parameters are correlated with each other and with discography findings, influencing the diagnostic performance of MRI. Combining MRI parameters improves the diagnostic performance of MRI, but only in the presence of moderate loss of nuclear signal. Discography will be most useful in discs with moderate loss of nuclear signal, particularly if there are no other MRI abnormalities present. | To determine the accuracy of MRI for diagnosis of discogenic pain, taking into consideration the interdependence of MRI parameters. |

| Carragee et al.,17 2009 | Modern discography techniques using small gauge needle and limited pressurisation resulted in accelerated disc degeneration, disc herniation, loss of disc height and signal and the development of reactive endplate changes compared to match-controls. | To compare progression of common degenerative findings between lumbar discs injected 10 years earlier with those same disc levels in matched subjects not exposed to discography. |

| Kang et al.,41 2009 | The proposed MRI classification is useful to predict an IVD with concordant pain. Disc protrusion with HIZ on MRI predicted positive discography in patients with discogenic low back pain. | To correlate MRI findings with pain response by provocation discography in patients with discogenic low back pain, with an emphasis on the combination analysis of HIZ and disc contour abnormalities. |

| Willems et al.,42 2007 | The preoperative status of adjacent levels as assessed by provocative discography did not appear to be related to the clinical outcome after fusion. | To evaluate whether the preoperative status of the adjacent discs, as determined by provocative discography, has an impact on the clinical outcome of lumbar fusion in chronic low back pain patients. |

| Shin et al.,43 2006 | Results of pain response were well correlated with intradiscal pressure but not with the amount of injected volume. | To investigate patients with suspected discogenic pain to determine pressure-volume relationships among morphologically abnormal discs and to determine diagnostic relevance of pressure-controlled discography in clinical decision-making. |

| Laslett et al.,7 2006 | In addition to the centralisation phenomenon, loss of lumbar extension and a history of persistent pain between acute episodes can be used individually or together as signs of possible discogenic pain. Further studies are needed to determine whether these 4 clinical variables are independent and can be used sequentially for diagnosis. | To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of clinical signs, self-reports, and other variables, in addition to the centralisation phenomenon, in relation to a concordant pain response to provocation discography. |

| Carragee et al.,44 2006 | Positive discography was not highly predictive in identifying isolated intradiscal lesions primarily causing chronic serious low back pain illness. | To evaluate the validity of a positive test result in provocative lumbar discography for the diagnosis of “discogenic pain” |

| Peng et al.,2 2006 | Vascular encroachment into the posterior annulus could be the reason why disrupted lumbar discs of some adults without chronic low back pain have HIZ, different from those of the painful disc. HIZ in the lumbar disc of the patient with low back pain could be considered a reliable marker of painful annular disruption. | To investigate the histology and clinical significance of an HIZ. |

| Lim et al.,11 2005 | Typical MRI findings with concordant pain at discography include Grade 4 or 5 disc degeneration and presence of an HIZ. Typical CT discography findings with concordant pain were fissured/ruptured discs and contrast extending into/beyond the outer annulus on CT. | To correlate MRI and CT discography findings with pain response at provocative discography in patients with discogenic back pain. |

| Laslett et al.,45 2005 | Centralisation of pain with the McKenzie method has a specificity of 89% or 100%, if the patient is calm or not severely disabled compared to a positive discography, respectively. | To estimate the diagnostic predictive power of centralisation and the influence of disability and patient distress on diagnostic performance, using provocation discography as a criterion standard for diagnosis, in CLBP patients |

| Derby et al.,6 2005 | Pain tolerance was significantly lower in asymptomatic patients. Negative patient discs and asymptomatic subject discs showed similar characteristics. Pressure-controlled manometric discography using strict criteria may distinguish asymptomatic discs among morphologically abnormal discs with Grade 3 annular tears in patients with suspected chronic discogenic LBP. | To determine if discography can distinguish asymptomatic discs among morphologically abnormal discs in patients with suspected chronic discogenic LBP and establish the standard characteristics of negative discs. |

APCD: automated pressure-controlled discography; CLBP: chronic low back pain; CT: computed tomography; HIZ: high-intensity zone; IVD: intervertebral disc; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Individual study characteristics.

| Authors | Type of study | Criteria for discography | Total number of the patients in the study | Number of patients undergoing discography | Number of discs operated | Criteria for positive discography | Pressure measurement | Adjacent disc | Greater pain on VAS | Positive discs | Negative discs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jain et al.,8 2021 | R | C/I | 576 | 50 | 109 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 6 | 40 | 10 |

| Son et al.,14 2021 | P | C/I | 92 | 78 | ? | PR | 0 | NS | 1 | 46 | ? |

| Torén et al.,15 2020 | P | C/I | 30 | 30 | 86 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 5 | 50 | 36 |

| McCormick et al.,19 2019 | P | C/I | 106 | 24 | 50 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 6 | 24 | ? |

| Chelala et al.,20 2019 | P | C | 736 | 736 | 2457 | PR | 0 | NS | 1 | 858 | 1599 |

| Wang et al.,21 2017 | P | I | 37 | 37 | 98 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 1 | 21 | 77 |

| Liu et al.,22 2018 | P | C/I | 46 | 46 | 60 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 1 | 43 | 17 |

| Kallewaard et al.,16 2018 | P | C/I | 50 | 50 | 50 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 6 | 50 | ? |

| Lee et al.,23 2017 | P | C/I | 36 | 17 | 17 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 6 | 17 | ? |

| Xi et al.,24 2016 | P | C | 43 | 43 | 126 | PR/Pr/AD | 0 | YES | 8 | 54 | 72 |

| Verrills et al.,25 2015 | P | C/I | 223 | 223 | 644 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 6 | 165 | 52 |

| Kim et al.,26 2015 | R | C/I | 72 | 72 | 183 | PR | A | NS | 1 | 83 | 100 |

| Hebelka et al.,27 2014 | P | I | 41 | 41 | 124 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 5 | 71 | 48 |

| Bartynski et al.,28 2013 | R | C/I | 150 | 150 | ? | PR | M | NS | 6 | 114 | 14 |

| Putzier et al.,29 2013 | P | C/I | 26 | 26 | 31 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 6 | 10 | 21 |

| Hebelka and Hansson,30 2013 | P | C/I | 41 | 35 | 119 | PR/Pr/AD | A | NS | 5 | 71 | 48 |

| Berg et al.,31 2012 | P | C | 140 | 140 | 411 | PR/Pr/AD | M | YES | 7 | 56 | 84 |

| Bartynski and Rothfus,32 2012 | P | C/I | 149 | 127 | 437 | PR/Pr/AD | M | NS | 6 | 242 | 195 |

| Derby et al.,33 2011 | R | I | 151 | 151 | 510 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 6 | 165 | 345 |

| Chen et al.,34 2011 | R | C/I | 93 | 93 | 256 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 6 | 116 | 140 |

| Alamin et al.,35 2011 | P | C/I | 52 | 50 | 100 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 5 | 88 | 12 |

| Derby et al.,36 2010 | P | C/I | 70 | 70 | 247 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 6 | 74 | 173 |

| Zhang et al.,37 2009 | P | C/I | 96 | 96 | 218 | PR | 0 | YES | 1 | 116 | 102 |

| Thompson et al.,38 2009 | R | C/I | 736 | 705 | 2457 | PR | 0 | YES | 1 | 1.220 | 1237 |

| Ohtori et al.,39 2009 | P | C | 42 | 27 | 27 | PR/Pr/AD | A | NS | 1 | 15 | 12 |

| O’Neill et al.,40 2008 | P | C/I | 143 | 143 | 460 | PR/Pr/AD | 0 | YES | 6 | 239 | 221 |

| Carragee et al.,17 2009 | P | C | 75 | 75 | 305 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 6 | 32 | 273 |

| Kang et al.,41 2009 | P | C/I | 62 | 62 | 178 | PR | 0 | YES | 1 | 44 | 134 |

| Willems et al.,42 2007 | P | C/I | 209 | 197 | 147 | PR | 0 | YES | 1 | 21 | 126 |

| Shin et al.,43 2006 | P | C/I | 21 | 21 | 51 | PR/Pr/AD | A | NS | 6 | 13 | 38 |

| Laslett et al.,7 2006 | P | C | 294 | 118 | 118 | PR/Pr/AD | M | YES | 1 | 81 | 37 |

| Carragee et al.,44 2006 | P | C | 78 | 62 | ? | PR/Pr/AD | A | NS | 6 | 30 | 32 |

| Peng et al.,2 2006 | P | C/I | 52 | 52 | 142 | PR/Pr/AD | 0 | NS | 1 | 17 | 125 |

| Lim et al.,11 2005 | P | C/I | 66 | 47 | 97 | PR/Pr/AD | 0 | YES | 1 | 34 | 63 |

| Laslett et al.,45 2005 | P | C/I | 118 | 118 | 133 | PR/Pr/AD | 0 | YES | 1 | 102 | 31 |

| Derby et al.,6 2005 | P | C/I | 106 | 106 | 337 | PR/Pr/AD | A | YES | 6 | 100 | 237 |

A: automated; AD: adjacent disc; C: clinical; C/I: clinical and imaging; I: imaging; M: manual; NS: not specified; P: prospective; Pr: pressure measurement; PR: pain response; R: retrospective; VAS: visual analogue scale; ?: no information available.

Quality assessment table of the QUADAS-2 studies.

| Studies | Risk of bias | Concerns of applicability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and time | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | |

| Jain et al.,18 2021 | |||||||

| Torén et al.,15 2020 | |||||||

| Son et al.,14 2021 | |||||||

| Chelala et al.,20 2019 | |||||||

| McCormick et al.,19 2019 | |||||||

| Wang et al.,21 2017 | |||||||

| Liu et al.,22 2018 | |||||||

| Kallewaard et al.,16 2018 | |||||||

| Lee et al.,23 2017 | |||||||

| Xi et al.,24 2016 | |||||||

| Verrills et al.,25 2015 | |||||||

| Kim et al.,26 2021 | |||||||

| Hebelka et al.,27 2014 | |||||||

| Putzier et al.,29 2013 | |||||||

| Bartynski et al.,28 2013 | |||||||

| Hebelka and Hansson,30 2013 | |||||||

| Bartynski and Rothfus,32 2012 | |||||||

| Berg et al.,31 2012 | |||||||

| Alamin et al.,35 2011 | |||||||

| Derby et al.,33 2011 | |||||||

| Chen et al.,34 2011 | |||||||

| Derby et al.,36 2010 | |||||||

| Carragee et al.,17 2009 | |||||||

| Ohtori et al.,39 2009 | |||||||

| O’Neill et al.,40 2008 | |||||||

| Thompson et al.,38 2009 | |||||||

| Zhang et al.,37 2009 | |||||||

| Kang et al.,41 2009 | |||||||

| Willems et al.,42 2007 | |||||||

| Laslett et al.,7 2006 | |||||||

| Shin et al.,43 2006 | |||||||

| Carragee et al.,44 2006 | |||||||

| Peng et al.,2 2006 | |||||||

| Lim et al.,11 2005 | |||||||

| Laslett et al.,45 2005 | |||||||

| Derby et al.,6 2005 | |||||||

Of the articles considered, 13 were retrospective in design and 23 were prospective studies. As criteria for discography to be determined as positive, 8 studies used only the pain response to the procedure, while 28 used more than one criterion during discography to classify it as positive. These criteria are shown in Table 2.

In a retrospective cohort study, Son et al. evaluated 46 patients with “intractable” discogenic pain (≥7 on the visual analogue pain scale) confirmed by discography, versus a control group of 46 patients with similar degenerative disc disease on imaging tests, but with mild low back pain (≤4 on the visual analogue pain scale). Despite the presented and exposed biases, the main bias being the difference in sagittal balance presented in the low back pain group considered intractable vs. controls, we were able to evaluate the discrepancies in disc height in both standing and supine positions, and the findings to diagnose discogenic low back pain. This was described as a potential metric for the detection of discogenic pain in early stages of intervertebral disc degeneration.14

In 30 patients undergoing discography, Torén et al. evaluated the impact of high intensity zones (HIZ) and their correlation with pain response during the procedure, with at least one negative control disc and performed with automated pressure control at less than 50psi. They demonstrated a relationship between the occurrence of HIZ and the pain response induced by the discography.15

In the evaluation of adjacent discs, 26 studies required at least one negative adjacent disc to consider discography as positive. In a prospective study of 50 patients aged 18–65 years with low back pain of more than 6 months’ duration, degenerative disc disease with Pfirrmann classification 2–4 and a poor response to facet joint medial branch block, Kallewaard et al. found no transfer of pressure to adjacent discs during pressure-controlled lumbar discography when performed at a rate of 0.02mL/s and at a pressure ≤15psi, making it unlikely that an equivocal pain response would occur as a false positive if these conditions were met.16

In terms of pain response threshold, 14 studies used a subjective scale indicating a pain response similar to or higher than the patient's usual pain response. Sixteen used the visual analogue pain scale (1 being mild pain and 10 being the worst pain ever experienced), with a threshold ≥6. Four studies used a threshold ≥5 and only 2 used a threshold ≥7 or 8 on the visual analogue scale. Only 5 studies formally express using the technique described by the SIS/IASP to determine a discography as positive.

DiscussionLow back pain is one of the most common conditions affecting adults. It is a disease that places a burden on health and labour systems due to the disability and deterioration in the quality of life of those who suffer from it.3 Findings on physical examination, diagnostic imaging, and clinical scales help to guide the diagnosis of the different aetiologies of low back pain. Low back pain of discogenic origin poses a diagnostic challenge. Previous publications have described clinical findings (axial low back pain, absence of radicular pain, exacerbation of pain when sitting, poor response to pain with facet and sacroiliac blocks) and findings on lumbar MRI (Pfirrmann >2, Modic type 2 changes, and HIZ) that are associated with low back pain of discogenic origin.9 Discography is proposed as a diagnostic method for discogenic low back pain.

There are those that oppose the use of discography. They question the validity of the symptoms provoked, the false positive rates in asymptomatic patients, and the suboptimal specificity it may have according to the diagnostic test protocol. Carragee et al. suggest that, despite the use of small needles, limiting contrast injection pressurisation during discography may result in accelerated disc degeneration, increased disc herniation, loss of disc height, and the development of reactive endplate changes compared to match-controls.17 McCormick et al. in their study of a cohort of patients over 7 years found no statistically significant evidence that these previously described degenerative changes were secondary to discography.19

The SIS clinical practice guidelines12 were published in 2013, which seek to standardise the criteria that should be evaluated when performing discography (Table 4). Only 5 studies explicitly expressed the use of the protocol and criteria proposed by the SIS. Because of these discrepancies, this study was proposed to determine the presentation and frequency of use of the different discogram findings for it to be determined as positive for discogenic low back pain.

SIS/IASP criteria for positive discogenic pain.

| 1. ≥6/10 concordant pain response |

| 2. 3mL total injected volume |

| 3. Pressurisation of disc no greater than 50psi over opening pressure |

| 4. Adjacent control disc(s) |

| a. For an adjacent control disc: |

| i. Painless response |

| or |

| ii. Non concordant pain that occurs at a pressure greater than 15psi over opening pressure |

| b. For 2 adjacent control discs: |

| i. Painless response at both levels |

| or |

| ii. Pain in one disc and one disc with non-concordant pain that occurs at a pressure greater than 15psi over opening pressure |

Modified from Bogduk et al.12.

The QUADAS-2 tool, a modification of the QUADAS instrument, was used to assess study quality. It seeks to evaluate the likelihood of bias and applicability of the systematic review following four phases given by the definition of the research question, the adaptation of the tool for its application in the systematic review, the review of the flowchart of the studies, and the evaluation of the bias and applicability of the different studies. The latter was conducted by two reviewers who, when discrepancies or lack of information in the article arose, reached a consensus to approve the assessment. This methodology reinforces the applicability of this study.

The percentage of studies with high risk of patient selection bias is given by the number of retrospective and prospective studies with case-control methodologies, non-randomised studies, possibly because invasive testing of large samples of patients who may or may not have the disease presents an ethical dilemma in the development of randomised clinical studies. However, since the interest of the study is to assess the criteria for considering a discography positive, they do not influence the applicability for this review. During the review of the different articles, it is clear that optimal pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment should be exhausted before invasive interventions are performed. Pain response during the procedure is the most influential criterion for a positive outcome in discogenic low back pain; however, its measurement can be subjective and depends on the patient. Speech limitations, intellectual capacity, cultural aspects, and the presence or absence of concomitant diseases in the person undergoing discography may limit their ability to adequately express pain by scoring it on a visual analogue pain scale or by comparing it with their usual pain. This review demonstrates, as do the guidelines proposed by the SIS, that with a response on the visual analogue pain scale ≥6 the greatest number of discographies are positive.

There are many reasons why injecting contrast into the disc can cause pain: stretching of damaged fibres of the annulus fibrosus, pressure on nerve endings associated with rupture of the annulus, the presence of vascular granulation tissue, substances such as lactic acid or glycosaminoglycans extravasated from the nucleus, or a sudden increase in pressure on the vertebral discs. It is therefore essential to clearly establish that the pain generated by the test must coincide with the pain reported by the patient prior to the test.46,47 There are false positive rates of up to 8.6%, presenting concordant pain, but with morphologically unaltered discs. Therefore, the aggregate presence of imaging changes such as HAZ, disc herniation, changes in the adjacent vertebral plates, help to achieve clinical and imaging congruence with the concordance of pain subjectivity described.47

Considering the heterogeneity of the terms for considering a test positive, positive figures have also been reported in the literature. A meta-analysis by Wolfer et al. showed a false positive rate of 9.3% per patient and 6% per disc in asymptomatic patients.48 Subsequent analyses showed a lower rate of 3% per patient, and studies with chronic patients without low back pain were also evaluated and showed a rate of 3% per patient and 2.1% per disc.18

Therefore, to determine the need or not to perform discography in a patient with low back pain, it is essential to appropriately evaluate the patient based on taking a history of the characteristics of the pain, physical examination aimed at differentiating the aetiologies of the low back pain, and diagnostic imaging (e.g., MRI) to evaluate the morphological features of the intervertebral disc and differential diagnoses of the genesis of the low back pain.

ConclusionsPain ≥6 in response to contrast injection, assessed with the visual analogue pain scale, was the most commonly used criterion in the studies included in this review. Although there are criteria for determining a discography as positive, different techniques and interpretations of discography findings to determine a positive discography for discogenic low back pain persist.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence i.

FundingNo external funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.