The low incidence and histological heterogeneity of primary sarcomas located in the pelvis make it difficult to find homogeneous cohorts.

ObjectiveTo describe the life and functional prognosis depending on the histological type of sarcoma in a series of locally advanced high-grade pelvis located sarcomas treated by hemipelvectomy.

MethodsA descriptive epidemiological and functional study was conducted on 15 cases treated between 2006 and 2012. Survival analysis, functional assessment, and a comparative study by histological type were performed, comparing chondrosarcomas to other histological diagnoses.

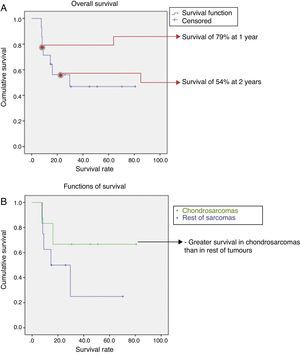

ResultsThe most frequent histological type was chondrosarcoma (46%), and the most frequent location was P2 (periacetabular) (73%). An internal hemipelvectomy was performed in 66% of cases, with a higher incidence (83%) in chondrosarcomas. Overall two-year survival was 54%, with higher survival in the chondrosarcoma group (67%) than in the other sarcomas (43%). Functional status depended on the type of intervention, with no differences in histological type or the performance of the reconstruction.

Discussion and conclusionsHemipelvectomy is a surgical procedure that is indicated for the treatment of locally advanced high grade pelvis located sarcomas, regardless of histological type. The incidence of limb preservation and overall survival is higher in chondrosarcomas compared to other sarcomas.

La baja incidencia y la heterogeneidad histológica de los sarcomas pélvicos primarios dificulta el análisis y publicación de cohortes homogéneas.

ObjetivoDescribir el pronóstico vital y funcional dependiendo del tipo histológico en una serie de sarcomas primarios de localización pélvica de alto grado localmente avanzados tratados mediante hemipelvectomía.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo, epidemiológico y funcional de 15 casos tratados entre 2006-2012. Se realizó análisis de supervivencia, valoración funcional y estudio comparativo en función del tipo histológico, comparando los condrosarcomas frente al resto de diagnósticos histológicos.

ResultadosEl tipo histológico más frecuente en la serie fue el condrosarcoma (46%), y la localización más frecuente la zona P2 (periacetabular) (73%). Se realizó una hemipelvectomía interna en el 66% de los casos, siendo mayor (83%) en el caso de los condrosarcomas. La supervivencia global a los 2 años fue del 54%, siendo más elevada en el grupo condrosarcoma (67%) que en el resto (43%). La situación funcional dependió del tipo de intervención, sin encontrar diferencias en función del tipo histológico ni de la realización de reconstrucción.

Discusio¿n y conclusionesLa hemipelvectomía como procedimiento quirúrgico está indicada para el tratamiento de los sarcomas primarios de localización pélvica de alto grado localmente avanzados independientemente del tipo histológico. La incidencia de conservación del miembro y la supervivencia global es mayor en los condrosarcomas frente al resto de tipos histológicos.

Sarcomas located in the pelvis present a worse prognosis than those located in the limbs, particularly due to their belated clinical manifestations and the absence of anatomical barriers in this location.1 This represents one of the most complex challenges faced by oncologic orthopaedic surgeons.2 Likewise, their surgical resection is enormously complex due to their local extension around anatomical structures with high functional value, with no delimited compartments between them.3 Hemipelvectomy is a surgical procedure with a profound impact for the patient at all levels, both functional and emotionally. In the last 2 decades, limb-preserving procedures (internal hemipelvectomies) have demonstrated their effectiveness due to the development of diagnostic techniques and adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies.4 At present, it is not possible to find protocols and guides for the management of these entities and, unlike in other medical disciplines, we can see that the number of published works is scarce. There are hardly any series with homogeneous cohorts in terms of diagnosis and stage that may serve to set the bases for a standardised management.1,5,6

The objective of this work is to present the long term survival and functional prognosis following hemipelvectomy in primary sarcomas located in the pelvis and locally advanced, differentiating between the histological variety of chondrosarcoma and the rest of sarcomas. The study also verified whether, as in previous series, chondrosarcoma presented better survival when including only high-grade sarcomas.

Material and methodsWe conducted a descriptive, epidemiological and functional study, comparing 2 cohorts according to their histological type: chondrosarcoma versus the rest of histological types. The study population were all consecutive patients treated at our centre by hemipelvectomy due to primary sarcomas located in the pelvis, including soft tissues, all of them of high grade and locally advanced, between January 2006 and December 2012. In order to obtain a sample homogeneity that facilitated the analysis of both the oncological and functional results, we included in the study all high grade and locally advanced sarcomas in which surgical resection compromised the stability of the pelvic ring. We excluded low grade sarcomas (G1), primary pelvic sarcomas with distant metastasis, and cases of pelvic metastasis of tumours with a primary origin in other locations. We also excluded sarcomas subsidiary of local treatment with a procedure other than hemipelvectomy. Thus, we decided to exclude pelvic Ewing sarcoma, which could be treated with radical radiotherapy in cases where obtaining adequate surgical margins was doubtful.7 Moreover, we also excluded sarcomas treated by partial resection which did not affect the integrity of the pelvic ring.

During the study period we attended a total of 15 patients, 4 females and 11 males, with a mean age of 46 years (range: 17–78 years), with no specific decade predominating in the age distribution. Of these cases, 6 had been treated previously at other centres and 5 had been referred to our centre with a diagnosis of local recurrence following several surgical interventions in all cases, albeit none of them through hemipelvectomy.

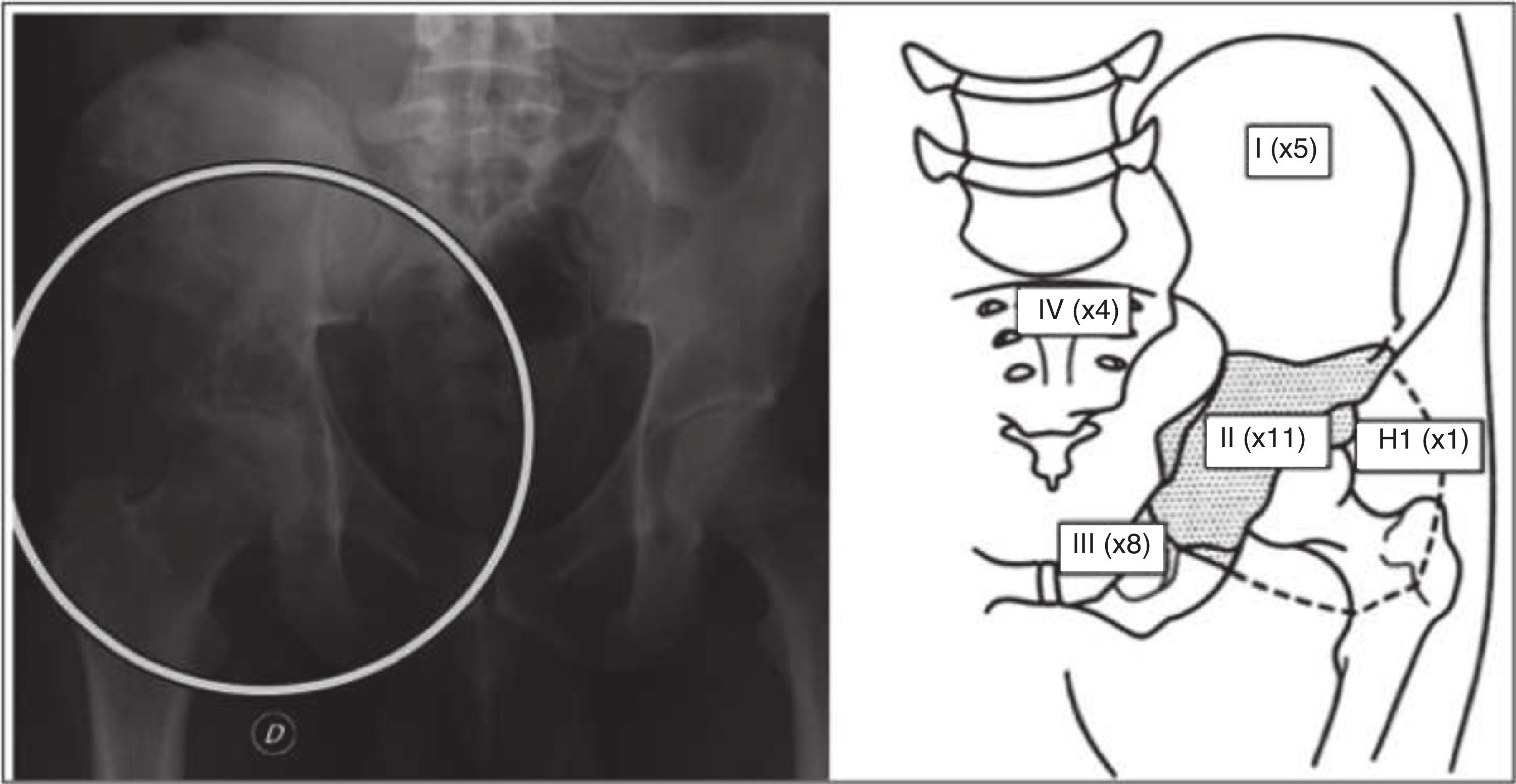

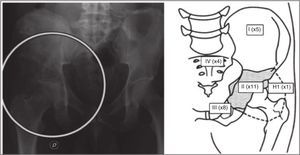

At the time of diagnosis, we recorded the histological type, the stage according to the Enneking classification8 and the location according to the affected bone structure9: ilium bone (P1), periacetabular region (P2), pubis (P3), sacrum (P4), proximal femur (H1) and combinations thereof. For the treatment, we considered the type of hemipelvectomy conducted and the surgical margins obtained, as well as the surgical complications. The type of resection was classified according to Enneking and Durham,8 dividing the resection into 4 types and the combinations thereof, whilst the surgical margins were divided according to MSTS7 into intralesional, marginal, wide and radical.

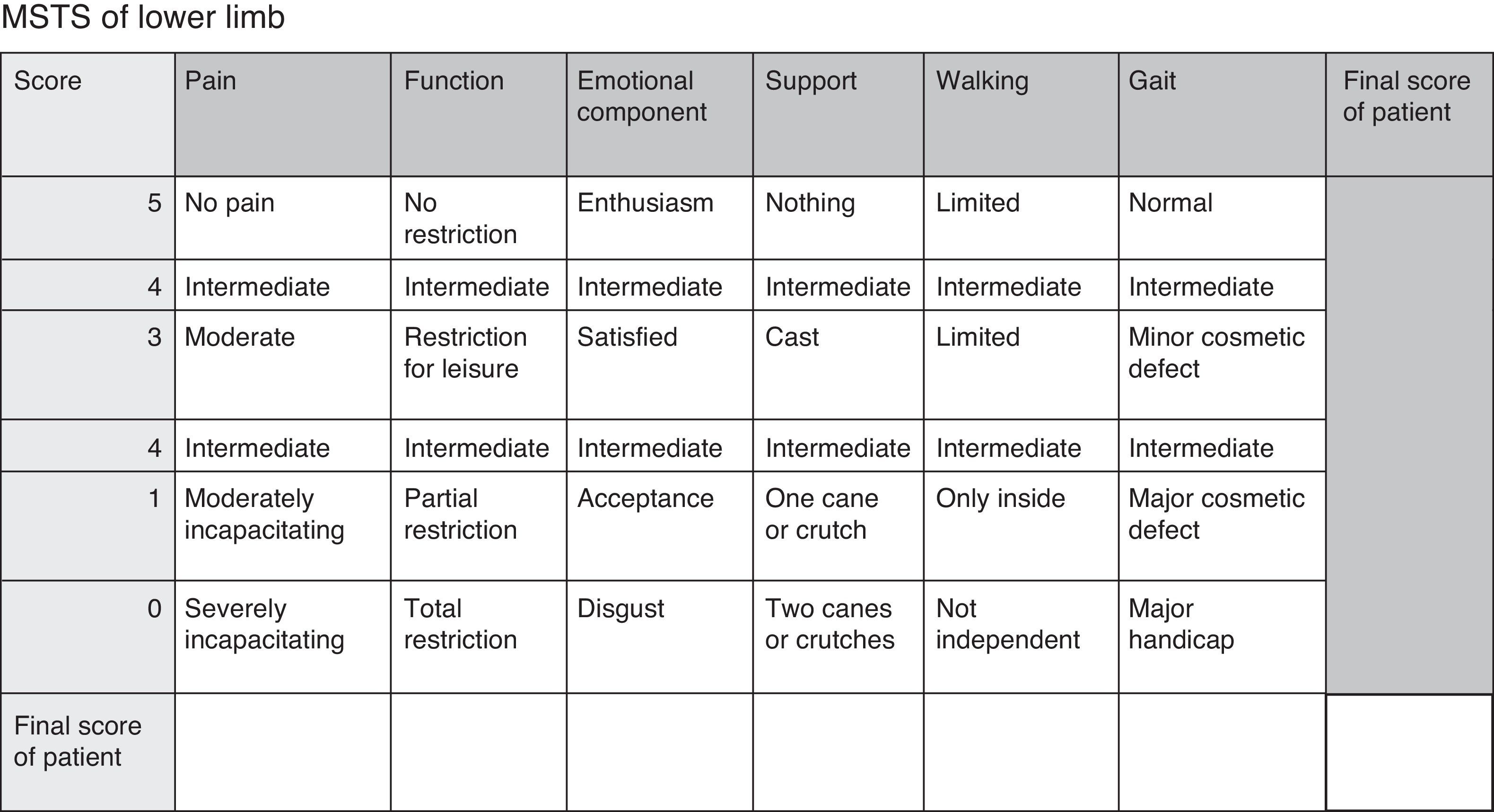

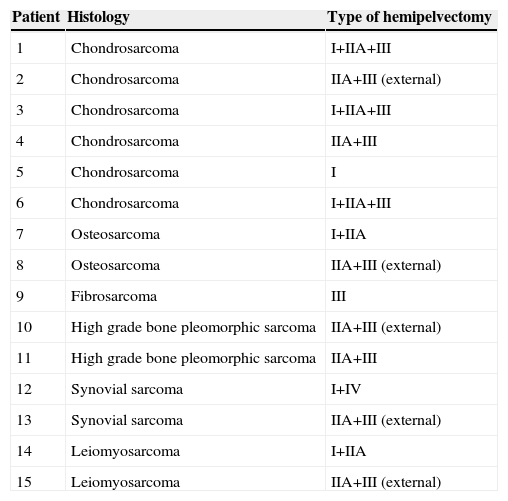

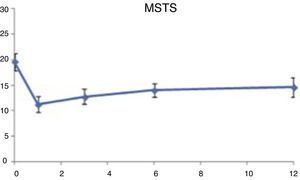

We carried out a prospective monitoring of this cohort for a minimum of 20 months, analysing the overall survival, appearance of local recurrence and distant metastasis, as well as functionality, comparing chondrosarcoma against the rest of sarcomas. The functional assessment employed the Musculoskeletal Tumour Society (MSTS) scale for lower limbs10,11 (Fig. 1).12 The assessment was carried out systematically upon admission and after 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 36 months.

MSTS functional scale for lower limbs.12

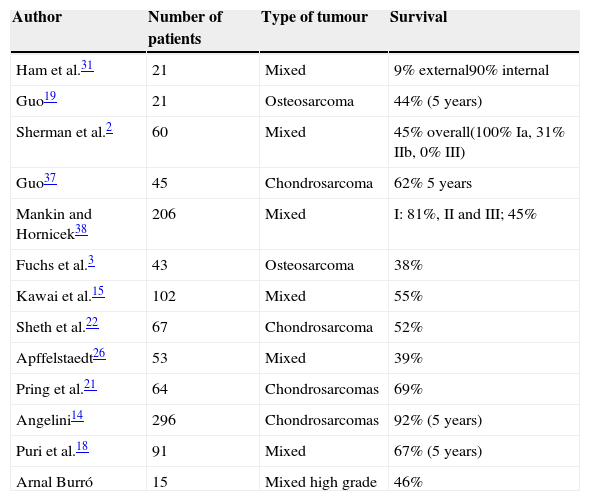

The most frequent histological diagnosis was chondrosarcoma (46%), and the most frequently affected region was the periacetabular (73% cases), followed by involvement of the obturator ring (53% cases) (Fig. 2). In 86.6% of cases, the initial stage at the time of diagnosis was stage IIb. We carried out 10 internal hemipelvectomies (66.66%) and 5 external hemipelvectomies (33.34%). Of the latter, 4 were sarcomas that persisted after previous treatments carried out at other centres (1 leiomyosarcoma, 1 synovial sarcoma, 1 osteosarcoma, 1 high grade pleomorphic sarcoma). In 86.66% of cases (13 patients) we carried out acetabular resection (resection II) including the hip joint (resection IIa) (Table 1).

Casuistry. Histology and type of surgical intervention.

| Patient | Histology | Type of hemipelvectomy |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chondrosarcoma | I+IIA+III |

| 2 | Chondrosarcoma | IIA+III (external) |

| 3 | Chondrosarcoma | I+IIA+III |

| 4 | Chondrosarcoma | IIA+III |

| 5 | Chondrosarcoma | I |

| 6 | Chondrosarcoma | I+IIA+III |

| 7 | Osteosarcoma | I+IIA |

| 8 | Osteosarcoma | IIA+III (external) |

| 9 | Fibrosarcoma | III |

| 10 | High grade bone pleomorphic sarcoma | IIA+III (external) |

| 11 | High grade bone pleomorphic sarcoma | IIA+III |

| 12 | Synovial sarcoma | I+IV |

| 13 | Synovial sarcoma | IIA+III (external) |

| 14 | Leiomyosarcoma | I+IIA |

| 15 | Leiomyosarcoma | IIA+III (external) |

We did not find any differences in terms of stages between the chondrosarcoma and non-chondrosarcoma groups. The main difference between both groups was the presence of prior surgery at another centre in 4 of the 9 sarcomas of the mixed group, versus 2 of the 6 chondrosarcomas.

In the chondrosarcoma group we carried out internal hemipelvectomy in 83% of cases, compared to 55% in the non-chondrosarcoma group. A total of 6 patients had been treated previously at other centres, and we were only able to perform internal hemipelvectomy in 2 cases (33%). Among patients in whom the initial surgical treatment was carried out at our centre, internal hemipelvectomy was performed in 88% of cases.

The resection margins were wide except in 1 case, where the resection was marginal. We performed reconstructive surgery of the pelvic ring in 3 cases, all of them in a second procedure (8 and 11 months after the hemipelvectomy), in 2 cases through allograft and total hip arthroplasty and in the other with a tailored pelvic reconstruction component and total hip arthroplasty11–13 (Fig. 3). The majority of cases suffered complications, with the most frequent being those related to the surgical wound (infection and dehiscence) (80% cases). Two thirds of these cases were polymicrobial, including Gram negative strains, with the most predominant being Pseudomona aeruginosa and Enterobacter cloacae, as well as anaerobic Gram positive cocci of the Peptostreptococcus gender. Cases in which a single microorganism was isolated included Staphylococcus aureus in 2 cases and multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii in the other. All infections were resolved with prolonged antibiotic therapy and surgical debridement.

It is worth highlighting 1 case of intraoperative death secondary to the appearance of ventricular tachycardia in a patient diagnosed with osteosarcoma referred to our centre for surgical treatment following disease progression in spite of neoadjuvant treatment. Two of the cases undergoing internal hemipelvectomy with periacetabular resection suffered neurapraxia of the sciatic nerve, in 1 case resolved 3 months after the intervention and in the other case remaining as a limitation for active extension of the ankle and foot with recovery of plantar sensitivity and flexor musculature. It is also worth commenting the appearance of 2 complications related to the urinary tract, 1 vesical fistula and 1 case of urethral fistulisation, both in patients treated previously by radical radiotherapy and suffering prostate carcinoma.

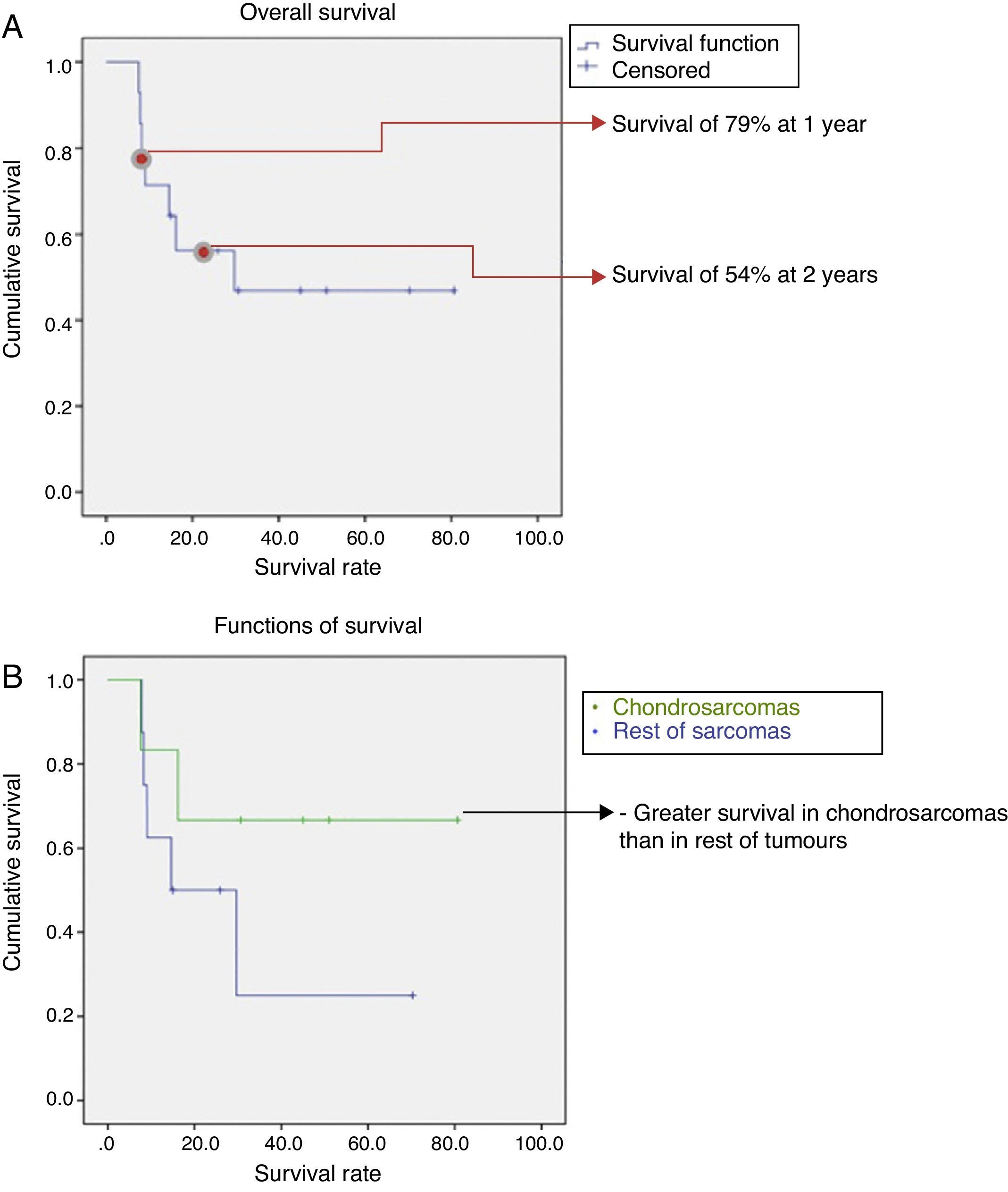

Monitoring lasted for a mean period of 30 months, with a range between 20 and 80 months. The overall survival was 46%, with a 1-year survival of nearly 80% and a decrease down to 54% at 2 years. After this point, survival remained constant until the end of follow-up (Fig. 4a). Taking into account the histological type, survival was better in chondrosarcomas compared to the rest of sarcomas (67% vs 43%) (Fig. 4b). We observed progression of the disease in 60% of cases in spite of surgical treatment, presenting as local recurrence in 2 cases (13%), distant disease in 5 cases (33%), and local recurrence with distant disease in another 2 cases. The most frequent location of metastatic disease was the lung. However, whilst in the chondrosarcoma group the progression with distant disease took place in 2 cases (33%), in the non-chondrosarcoma group it took place in 5 cases (55%).

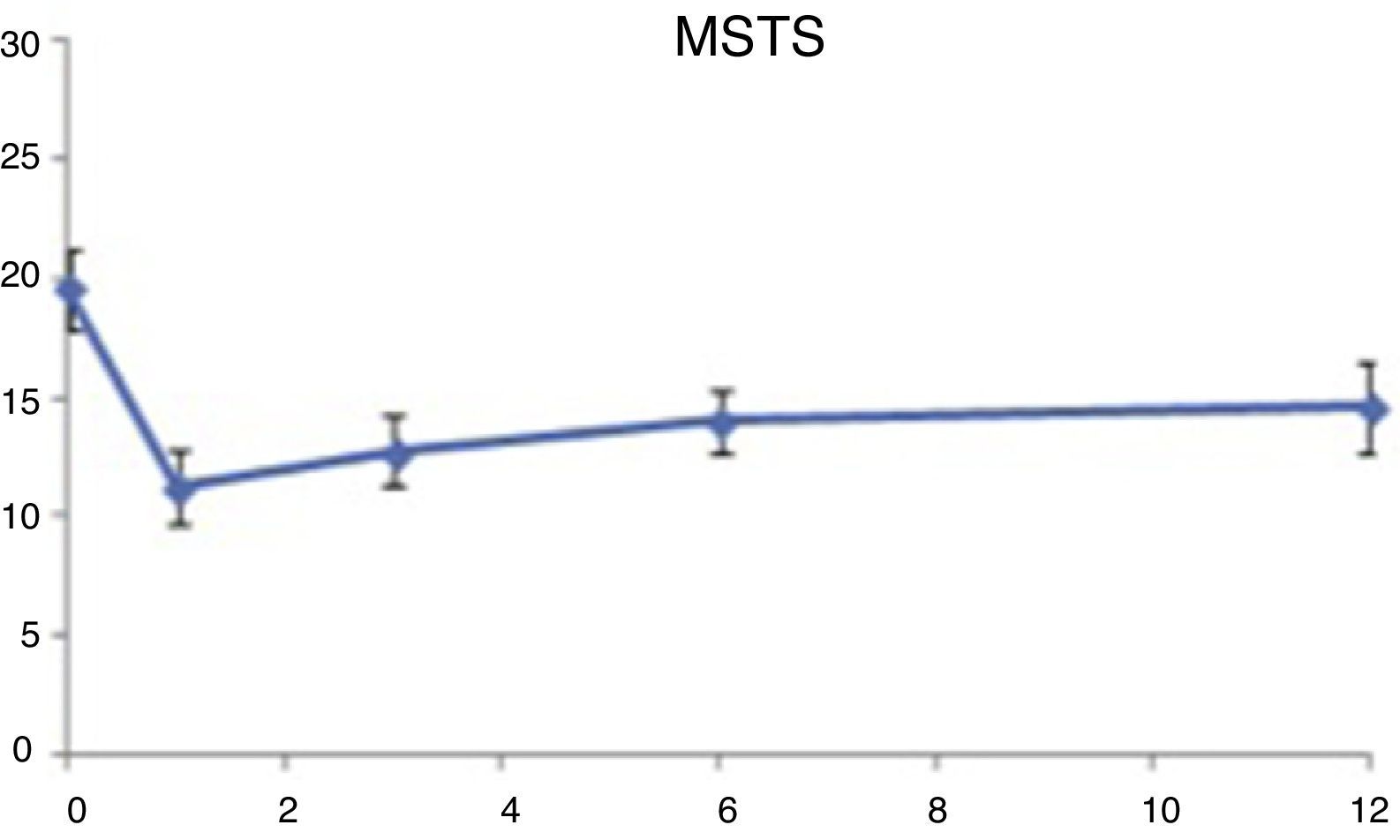

The functional evaluation registered that patients began from a point with no excessive clinical and functional involvement (mean value=20 points; score 66%), given the scarce manifestation of tumours in this location. In the postoperative period, patients reported a lower functional score, which gradually improved over the following months, remaining without significant variations after 1 year. Functional involvement was greater in the external hemipelvectomy group compared to the internal, with no differences according to the histological type being observed (Fig. 5).

DiscussionAlthough hemipelvectomies represent the main therapeutic option in the treatment of sarcomas located in the pelvis, it is not easy to find other publications with which to compare our results, as there are very few series based on this surgical procedure. There are even fewer if we rule out cases due to other causes, like trauma, gynaecological tumours and carcinomas in general. Those works dealing with sarcomas in this location, entities with a natural evolution leading to a fatal prognosis, focus on a specific surgical technique or a particular aspect of the treatment. The relevant series, around 30, are all retrospective analyses of the experience at different hospitals, with series ranging from 4 to 5 patients to little over 100, given the scarce incidence of these sarcomas. In some cases, they are limited by the combination of treatments, which occasionally present results comparable to surgical treatment, without having been able to prove their superiority, as in the case of Ewing sarcoma,7 which in turn is one of the most frequent sarcomas treated by hemipelvectomy in many of the published series. Although the main treatment is still surgical resection, some centres propose radical radiotherapy in cases in which obtaining wide resection margins is doubtful.13

In our cohort, the exclusion of disseminated sarcomas and those sarcomas with a possibility of nonsurgical treatment, such as Ewing sarcoma, was applied in order to avoid selection bias and with an awareness of the limitation of the sample size for extrapolation of results.

The prospective time design enabled us to record the functional condition of patients in a more precise manner, which improved the understanding of the impact of these interventions. Our cohort had an age range comparable to that in other works reviewed, with a homogeneous age distribution after the second decade of life. Excluding Ewing sarcoma made the number of children and young adults scarce in this series, which is the main difference with other works that did include it. The majority of published series14–18 identify chondrosarcoma as the most frequent pelvic bone sarcoma, followed by osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. This distribution was maintained in our series, as we found 40% of chondrosarcomas versus 60% of other histological types. It is worth noting the exclusion of low grade tumours from our cohort, in order to improve sample homogeneity. This fact is in contrast with the majority of published series.16,18–22

Obtaining safe surgical margins, marked by variables such as tumour extension or possibility of responding to adjuvant treatment, was the main conditioning factor when considering limb-preserving surgery.19,23 In this series we carried out limb-preserving surgery or internal hemipelvectomy in 66% of cases. One of the key findings was the higher incidence of internal hemipelvectomy when the diagnosis was of chondrosarcoma and if patients had not been treated previously at other centres. If we add to this the progression of the disease in all patients referred after undergoing previous surgical procedures, it appears that their initial referral to reference centres was appropriate.16

The series reflects a high percentage of surgical complications, similar to that reported by most published series.10,18,19,24–28 It is worth highlighting higher rates of infection and dehiscence than other publications, although resolved in all cases through debridement and antibiotic therapy. If we add to this the existence of works reflecting an increase in the rate of complications on reconstruction arthroplasties among these patients in up to 60–70% of cases,20,25,27,29–34 this justifies the low percentage of cases in our series undergoing reconstructive surgery after internal hemipelvectomy. Prosthetic infection and tumour recurrence were identified as the most frequent causes of failure, occasionally leading to a conversion to external surgery (5.3%).34 The rate of infection in reconstructive surgery in one procedure was 13% higher compared to just resection.20,29,35 This was a significant source of controversy and patient selection is vital when considering reconstructive surgery after resection of a tumour. Some authors, like Puri et al., did not find any differences in functionality between patients with or without reconstruction, but did find them based on the resection performed, with similar results to those reported in our series.18 In our case, functionality in patients with reconstruction was not analysed, as this was performed very close to the end of the monitoring period.

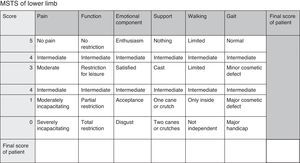

Overall survival is one of the most variable data points identified in the different publications (Table 2). The causes were manifold, mainly the mix of prognostic variables acting as modifying factors. The histological type was a variable to be taken into account in the majority of hemipelvectomy series published. Pelvic resections in chondrosarcomas present higher overall survival than pelvic resections published in series of osteosarcomas or malign tumours with no histological distinction; a similar conclusion to that reached by the present work.

Survival following pelvic sarcomas according to different authors.

| Author | Number of patients | Type of tumour | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ham et al.31 | 21 | Mixed | 9% external90% internal |

| Guo19 | 21 | Osteosarcoma | 44% (5 years) |

| Sherman et al.2 | 60 | Mixed | 45% overall(100% Ia, 31% IIb, 0% III) |

| Guo37 | 45 | Chondrosarcoma | 62% 5 years |

| Mankin and Hornicek38 | 206 | Mixed | I: 81%, II and III; 45% |

| Fuchs et al.3 | 43 | Osteosarcoma | 38% |

| Kawai et al.15 | 102 | Mixed | 55% |

| Sheth et al.22 | 67 | Chondrosarcoma | 52% |

| Apffelstaedt26 | 53 | Mixed | 39% |

| Pring et al.21 | 64 | Chondrosarcomas | 69% |

| Angelini14 | 296 | Chondrosarcomas | 92% (5 years) |

| Puri et al.18 | 91 | Mixed | 67% (5 years) |

| Arnal Burró | 15 | Mixed high grade | 46% |

However, it is not easy to find homogenous samples that avoid mixing histological grades (with low grade cases often being included), as well as staging. These are the 2 prognostic factors with most extensive evidence.2,3,14,15,21,22,31,36,37 In our cohort, survival between the first and second year decreased from nearly 80% to 54%, reaching 46% at the end of the follow-up period, thus reflecting a stability in the rate of overall survival after the second year.

If we compare survival in series like that by Guo,37 which dealt with osteosarcomas, the survival figure is very similar to ours (44%). The mixed series by Sherman2 is an adequate example of how survival decreases from 100% in stage Ia to 31% in stage IIb, the stage corresponding to most of our patients. In their series, Mankin et al. concluded that there were significant differences in survival when comparing stage I with stages II and III (81% vs 45%), without any significant differences being identified between stage II and stage III.38

Other works, like those by Pring21 and Angelini,14 dealing exclusively with chondrosarcomas, report much higher figures, as is also the case with the subgroup of chondrosarcomas in our series, always with the sample size limitation preventing the differences identified from reaching significant values. We believe that, since the grade, and consequently the stage, have been proven to have a higher causal association with prognosis than histological diagnosis, samples should be obtained taking these factors into account.

The functional assessment and evolution coincide with those of other published works.11 Patients undergoing internal hemipelvectomy displayed higher values than those in whom it was necessary to perform external hemipelvectomy (15 points, equivalent to a score of 50%, in internal hemipelvectomies vs 12 points, equivalent to a score of 40% in external hemipelvectomies). Although this is also reported by other published series,21 some works have not observed any differences.10

Therefore, hemipelvectomy would be indicated for the treatment of high grade, locally advanced pelvic sarcomas, regardless of their histological type, although with a higher number of internal hemipelvectomies and better overall survival in chondrosarcomas. As main limitations of the study it is worth mentioning the inclusion of only high grade locally advanced sarcomas, preventing the assessment and analysis of survival based on histological grade, as well as the sample size, which prevented the level of statistical significance from reaching 95%. It seems necessary to carry out reviews of pure series of high grade sarcomas, as this was the prognostic factor with the highest causal association.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

FinancingIn case the work entitled “Hemipelvectomy for the treatment of high-grade sarcomas: Prognosis in chondrosarcomas compared to other histological types” is published, the signing authors transfer all rights to the Spanish Journal of Traumatology and Orthopaedic Surgery (Revista Española de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología), which will own all the material submitted.

The signing authors state that the article submitted is an original work. The authors have not received any financial aid to carry out this work and have not signed any agreement entitling them to receive benefits or payment from any commercial entity.

No commercial entity has made or will make any payments to any foundations, educational institutions or any other non-profit organisation to which the authors are affiliated.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Arnal-Burró J, Calvo-Haro JA, Igualada-Blazquez C, Gil-Martínez P, Cuervo-Dehesa M, Vaquero-Martín J. Hemipelvectomías tras sarcomas de localización pélvica de alto grado: pronóstico en condrosarcomas frente a otros tipos histológicos. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;60:67–74.