Hip fractures are very common injuries in elderly patients and are associated with increased mortality.

ObjectiveTo identify the factors associated with mortality in patients after one year of being operated for hip fracture in an Orthogeriatric Program.

MethodsWe design an observational analytical study in subjects older than 65 years admitted to the Hospital Universitario San Ignacio for hip fracture who were treated in the Orthogeriatrics Program. Telephone follow-up was performed one year after admission. Data were analyzed using a univariate logistic regression model and a multivariate logistic regression model was applied to control the effect of the other variables.

ResultsMortality was 17.82%, functional impairment was 50.91%, and institutionalization was 13.9%. The factors associated with mortality were moderate dependence (OR=3.56, 95% CI=1.17–10.84, p=0.025), malnutrition (OR=3.42, 95% CI=1.06–11.04, p=0.039), in-hospital complications (OR=2.80, 95% CI=1.11–7.04, p=0.028), and older age (OR=1.09, 95% CI=1.03–1.15, p=0.002). The factor associated with functional impairment was a greater dependence at admission (OR=2.05, 95% CI=1.02–4.10, p=0.041), and with institutionalization was a lower Barthel index score at admission (OR=0.96, 95% CI=0.94–0.98, p=0.001).

ConclusionsOur results shows that the factors associated with mortality one year after hip fracture surgery were: moderate dependence, malnutrition, in-hospital complications and advanced age. Having previous functional dependence is directly related to greater functional loss and institutionalization.

Las fracturas de cadera son lesiones muy comunes en pacientes adultos mayores y se relacionan con aumento de la mortalidad.

ObjetivoIdentificar los factores asociados a la mortalidad en pacientes al año de haber sido operados de fractura de cadera en un Programa de Ortogeriatría.

MétodosEstudio observacional analítico en sujetos mayores de 65 años ingresados en el Hospital Universitario San Ignacio por fractura de cadera y que fueron atendidos en el Programa de Ortogeriatría. Se realizó seguimiento telefónico un año después del ingreso. La información se analizó a través de un modelo de regresión logística univariada y para controlar el efecto de las demás variables se aplicó un modelo de regresión logística multivariada.

ResultadosLa mortalidad en la población intervenida fue del 17,82%, la pérdida funcional fue del 50,91% y la institucionalización del 13,9%. Los factores asociados a mortalidad con significación estadística fueron: dependencia moderada (OR=3,56; IC 95%=1,17-10,84; p=0,025), desnutrición (OR=3,42; IC 95%=1,06-11,04; p=0,039), presentar complicaciones intrahospitalarias (OR=2,80; IC 95%=1,11-7,04; p=0,028), y mayor edad (OR=1,09; IC 95%=1,03-1,15; p=0,002). El factor asociado con pérdida funcional fue tener una mayor dependencia al ingreso (OR=2,05; IC 95%=1,02-4,10; p=0,041), y con institucionalización fue tener menor puntaje en el índice de Barthel al ingreso (OR=0,96; IC 95%=0,94-0,98; p=0,001).

ConclusionesEn la población estudiada los factores asociados a la mortalidad al año de la cirugía por fractura de cadera son: dependencia moderada, desnutrición, complicaciones intrahospitalarias y edad avanzada. Tener dependencia funcional previa está directamente relacionado con mayor pérdida funcional e institucionalización.

Hip fracture is one of the causes of morbidity and mortality in the elderly population and involves significant clinical deterioration.1,2 It has been described that hospital mortality due to hip fracture is between 4% and 8%, with an increase at one year of up to 30%, and even at 3 and 7 years with a mortality rate of 50% and 70%, respectively.1,3 Various factors associated with mortality have been described in the literature, including age (over 80 years); male sex; the existence of geriatric syndromes such as frailty; functional status; dementia; comorbidities; pre-existence of severe anaemia (haemoglobin less than 7); waiting time for surgery; type of fracture and institutionalization. Likewise, these subjects, one year after being operated on, present a loss of functionality and, although due to the heterogeneity of the patients it is difficult to evaluate which of these factors have a particular influence, it has been described that having a previous dependency for basic activities of daily living, suffering dementia and being institutionalized at the time of the hip fracture would be direct triggers.4,5

In several studies, it has been reported that mortality from hip fracture can be seen as late as 10 years later. For those who survive, the acute hospital costs are substantial, but the long-term costs in rehabilitation and extra care in the community are even higher, because hip fractures, together with hospitalization involve a number of risks, such as perioperative complications; deep vein thrombosis; acute pulmonary embolism; pressure ulcers, urinary tract infections; malnutrition; delirium, and functional decline.1,5 Late mortality can be expected to be influenced by both the pathology (health status) and the social and health care factors that accompany each individual patient.

Studies have shown that the mortality of people living in a nursing home prior to hip fracture exceeds that of people living in the community.6–8 Between 15% and 30% of those living at home at the time of hip fracture require institutionalization, and a number of associated causes have been described, such as being over 80 years of age, multimorbidity, and dementia.1,5

Several studies have been conducted worldwide on the risk factors associated with one-year mortality in patients undergoing surgery for hip fracture in different populations. However, geographically the results are heterogeneous. Specifically in Colombia, studies of this type are scarce. Identifying the most relevant factors with respect to the national reality will allow us to contribute to the limited literature, whilst simultaneously helping us to implement actions to improve the results in the short and medium term through comprehensive geriatric assessment and improved care protocols established at the Hospital Universitario San Ignacio (HUSI). Moreover, these data can be extrapolated to other hospitals with similar characteristics to ours.

The main objective of this study was therefore to determine the factors which trigger mortality, functional loss and institutionalization one year after hip fracture surgery in the HUSI Orthogeriatrics Programme.

Materials and methodsAn analytical observational retrospective cohort study was conducted in patients over 65 years of age with non-pathological hip fracture (defined as fracture caused by bone fragility), taken to surgical management and treated in the context of the HUSI Orthogeriatrics Programme between January 2017 and September 2020. A review of the data recorded in the medical records was carried out and a telephone follow-up was performed one year after discharge.

The inclusion criteria for this study were: being 65 years of age or older, admitted for hip fracture and having undergone surgical management at the hospital. The exclusion criteria were not having been operated on through the Hospital Orthogeriatric Programme, having a pathological fracture (defined as a fracture caused by neoplastic lesions, for which the images in the medical records were reviewed, excluding those with metastatic lesions), and having been referred to another hospital during the process of care.

The dependent variable was mortality, defined as having died one year after the occurrence of the surgery. Secondary outcomes were defined as the loss of function – measured as the decrease of more than 10 points on the Barthel scale at one year, compared with the score prior to the fracture, and institutionalization – understood to be whether the patient was admitted to a care site classified as a nursing home, an old peoples’ home or long-stay unit during the same time interval.

Regarding the independent variables, the demographic variables were organized as: sex (male or female); age (in years); origin (home or care institution); the baseline situation prior to surgery, which included: the presence of malnutrition (a score less than or equal to 7 on the Mini Nutritional Assessment screening version); functionality prior to the fracture (according to the Barthel index score); the presence of a previous diagnosis of dementia, and a poor support network (defined dichotomously according to whether or not an adequate support network was identified on admission according to a semi-structured interview). Regarding comorbidities, the number of comorbidities was included (as a continuous variable), as well as the presence of polypharmacy (defined as receiving 5 or more drugs in the pharmacological history in the admission history); falls or fractures prior to admission and type of fracture (intracapsular and extracapsular). Data related to care during the hospital stay included time to surgery (measured in hours); type of anaesthesia (general or spinal); type of surgery (arthroplasty or osteosynthesis) and length of hospital stay (days); The following data were also collected: blood tests in the first 48h after admission; haemoglobin (measured in grams per decilitre); creatinine (measured in milligrams per decilitre); the presence of hospital complications (delirium, infection, cardiac, thromboembolic, pressure or lung injury); the need for transfusion; intensive care unit admission requirement, and in-hospital mortality.

Sample size calculation was obtained by performing the probability estimation seeking to compare with a proportion in reference values (mortality described in the literature of 30%),7,8 with an alpha error of .05, power of 80%, assuming absolute frequency of 9% and relative frequency of 30%, which allows a minimum sample size of 202 persons, with an expected loss to follow-up of less than 10%.

A descriptive analysis of the information was carried out. For continuous variables, averages and standard deviations are reported in the case of normally distributed variables, or medians and interquartile ranges in the case of variables that did not meet this assumption. In the case of categorical variables, frequency tables and/or percentages were created.

For factors associated with mortality, functional loss and institutionalization, a univariate logistic regression model was used. For measures of association, the Chi-square test was used for dichotomous variables, and continuous variables were defined using the Mann–Whitney U-test to determine whether there were statistically significant differences. The effect of the other variables was controlled by applying a multivariate logistic regression model considering confounding and modifying variables. The odds ratios (OR) obtained were reported, together with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Data were analyzed using the STATA 16.1 statistical package. The level of statistical significance was set at p<.05.

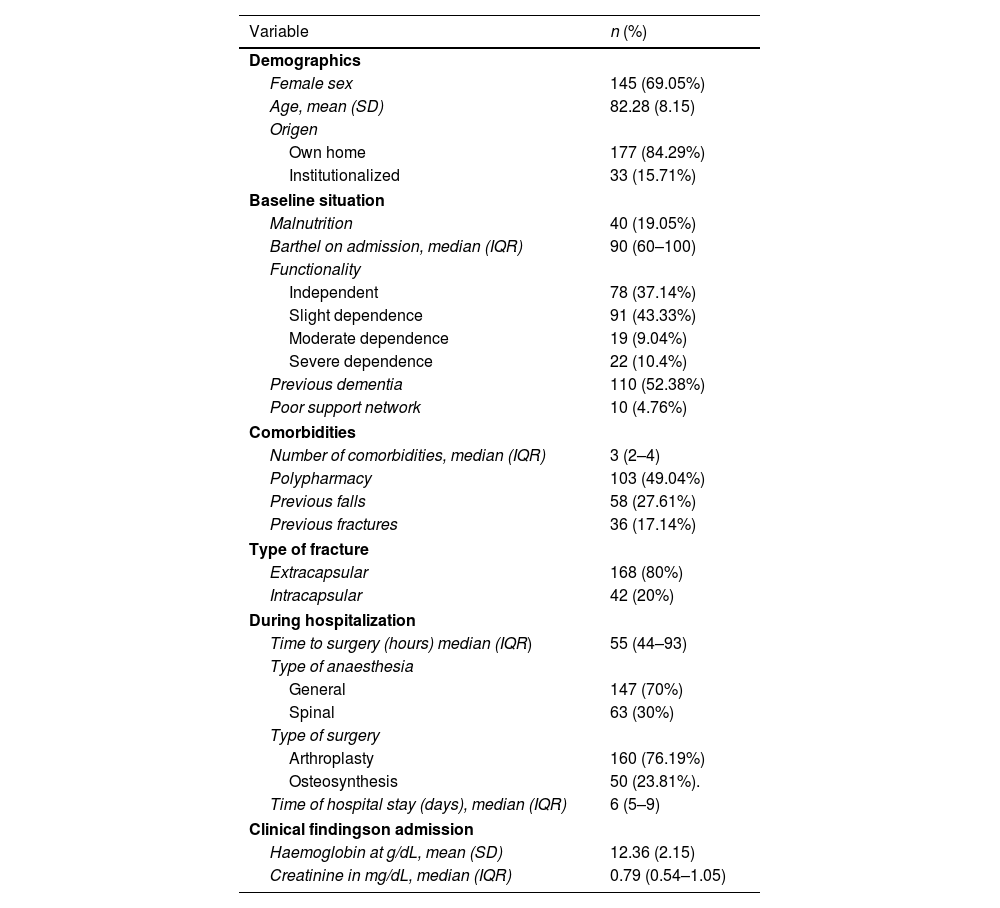

ResultsData were collected from the medical records of 210 subjects. Subsequently, a telephone follow-up was carried out one year after the surgical procedure. A total of 202 subjects were included with 8 of them lost to follow-up, equivalent to 3.81%. The results are presented below.

Of the 210 subjects included in the study, 69.05% of the population was female, with a mean age of 82.28 (8.15) years, and 84.29% were from their own homes. In terms of baseline status, 19.05% were malnourished. At the functional level, the median Barthel index prior to the fracture was 90, with 43.3% of the subjects having slight dependence and 4.76% having a poor support network. In addition, a history of dementia prior to the hip fracture was found in 52.38%. The average number of comorbidities was 3 (2–4), the most frequent being high blood pressure (69.83%). Regarding polypharmacy, this was present in 49.04% of the subjects.

The most frequent type of fracture was extracapsular, representing 80%. The median time to surgery in hours was 55 (range 44–93) and days of stay 6 (range 5–9); the most frequent type of anaesthesia was general in 70% of cases; the most frequent type of surgery was arthroplasty in 76.19%. Additionally, 50.95% presented some hospital complication, the most frequent being delirium (28.57%). The requirement for transfusion support during hospitalization was 30%. In-hospital mortality was 2.97%.

With respect to the primary outcome, mortality at one year was 17.82%. In the secondary outcomes, functional loss was 40%, and institutionalization at one year was 10.95% (see Table 1).

Population characteristics (n=210).

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Female sex | 145 (69.05%) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 82.28 (8.15) |

| Origen | |

| Own home | 177 (84.29%) |

| Institutionalized | 33 (15.71%) |

| Baseline situation | |

| Malnutrition | 40 (19.05%) |

| Barthel on admission, median (IQR) | 90 (60–100) |

| Functionality | |

| Independent | 78 (37.14%) |

| Slight dependence | 91 (43.33%) |

| Moderate dependence | 19 (9.04%) |

| Severe dependence | 22 (10.4%) |

| Previous dementia | 110 (52.38%) |

| Poor support network | 10 (4.76%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Number of comorbidities, median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) |

| Polypharmacy | 103 (49.04%) |

| Previous falls | 58 (27.61%) |

| Previous fractures | 36 (17.14%) |

| Type of fracture | |

| Extracapsular | 168 (80%) |

| Intracapsular | 42 (20%) |

| During hospitalization | |

| Time to surgery (hours) median (IQR) | 55 (44–93) |

| Type of anaesthesia | |

| General | 147 (70%) |

| Spinal | 63 (30%) |

| Type of surgery | |

| Arthroplasty | 160 (76.19%) |

| Osteosynthesis | 50 (23.81%). |

| Time of hospital stay (days), median (IQR) | 6 (5–9) |

| Clinical findingson admission | |

| Haemoglobin at g/dL, mean (SD) | 12.36 (2.15) |

| Creatinine in mg/dL, median (IQR) | 0.79 (0.54–1.05) |

| In-hospital complication | 107 (50.95%) |

| Delirium | 60 (28.57%) |

| Infection | 19 (9.05%) |

| Cardiac | 4 (1.90%) |

| Thomboembolique | 3 (1.43%) |

| Pressure ulcer | 3 (1.43%) |

| Pulmonary | 1 (.45%) |

| Transfusion requirement | 63 (30%) |

| ICU requirement | 8 (3.81%) |

| Intrahospital mortality | 6 (2.97%) |

| Outcomes at one year | |

| Losses to follow-up | 8 (3.81%) |

| Mortality at one year | 36 (17.82%) |

| Barthel at one year | 80 (50–90) |

| Functional loss at one year | 84 (40.00%) |

| Institutionalization at one year | 23 (10.95%) |

g/dL: grams per decilitre; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range; mEq/L: milliequivalents per litre; mg/dL: milligrams per decilitre; SD: standard deviation.

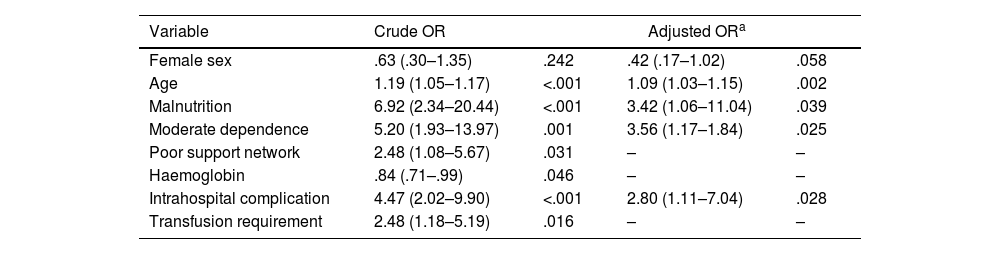

In the bivariate analysis between mortality at one year and the independent variables, statistically significant differences were found with older age, with a mean of 87.7 years (p<.001); poor support network 30.56% (p=.028); moderate dependency 25% (p<.001); malnutrition 88.89% (p<.001); having hospital complications 72.22% (p<.001) (see Table 2). Factors related to mortality, organized by magnitude of association, were moderate dependency (OR=3.56, 95% CI=1.17–10.84, p=.025), malnutrition (OR=3.42, 95% CI=1, 06–11.04, p=.039), having in-hospital complication (OR=2.80, 95% CI=1.11–7.04, p=.028), and being older (OR=1.09, 95% CI=1.03–1.15, p=.002) (see Table 3).

Bivariate analysis between mortality at one year and associated variables (n=202).

| Variable | Deceased n=36 (17.82%) | Alive n=166 (82.18%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 22 (61.11%) | 118 (71.08%) | .240 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 87.75 (8.26) | 81.10 (7.63) | <.001 |

| Malnourished | 32 (88.89%) | 89 (53.61%) | <.001 |

| Independent | 4 (11.11%) | 72 (43.37%) | <.001 |

| Slight dependence | 20 (55.56%) | 66 (39.76%) | .082 |

| Moderate dependence | 9 (25.00%) | 10 (6.02%) | <.001 |

| Severe dependence | 3 (8.33%) | 18 (10.84%) | .655 |

| Previous dementia | 26 (72.22%) | 82 (49.40%) | .013 |

| Poor support network | 11 (30.56%) | 25 (15.06%) | .028 |

| Number of comorbidities, median (IQE) | 3 (2.5–4) | 3 (2–4) | .055 |

| Polypharmacy | 21 (58.33%) | 79 (47.59%) | .243 |

| Previous falls | 9 (25.00%) | 46 (27.88%) | .726 |

| Previous fracture | 6 (16.67%) | 28 (16.87%) | .977 |

| Extracapsular fracture | 31 (86.11%) | 130 (78.31%) | .292 |

| Arthroplasty | 30 (83.33%) | 124 (74.70%) | .270 |

| Time to surgery hours, median (IQR) | 55 (47–96) | 54 (44–94) | .501 |

| General anaesthesia | 23 (63.89%) | 117 (70.48%) | .437 |

| Hospital stay days, median (IQR)) | 7 (5–12.5) | 6 (5–8) | .066 |

| Haemoglobin in g/dL, media (SD) | 11.67 (1.97) | 12.48 (2.20) | .043 |

| Creatinine in mg/dL, median (IQR) | .82 (.65–1.325) | .78 (.45–1.01) | .219 |

| Intrahospital complication | 26 (72.22%) | 61 (36.75%) | <.001 |

| Transfusion requirement | 17 (47.22%) | 44 (26.51%) | .014 |

| ICU requirement | 2 (5.56%) | 6 (3.61%) | .588 |

g/dL: grams per decilitre; HBP: high blood pressure; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range; mEq/L: milliequivalents per litre; mg/dL: milligrams per decilitre; SD: standard deviation.

Multivariate logistic regression between mortality and associated factors.

| Variable | Crude OR | Adjusted ORa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | .63 (.30–1.35) | .242 | .42 (.17–1.02) | .058 |

| Age | 1.19 (1.05–1.17) | <.001 | 1.09 (1.03–1.15) | .002 |

| Malnutrition | 6.92 (2.34–20.44) | <.001 | 3.42 (1.06–11.04) | .039 |

| Moderate dependence | 5.20 (1.93–13.97) | .001 | 3.56 (1.17–1.84) | .025 |

| Poor support network | 2.48 (1.08–5.67) | .031 | – | – |

| Haemoglobin | .84 (.71–.99) | .046 | – | – |

| Intrahospital complication | 4.47 (2.02–9.90) | <.001 | 2.80 (1.11–7.04) | .028 |

| Transfusion requirement | 2.48 (1.18–5.19) | .016 | – | – |

a Model adjusted by age and sex.

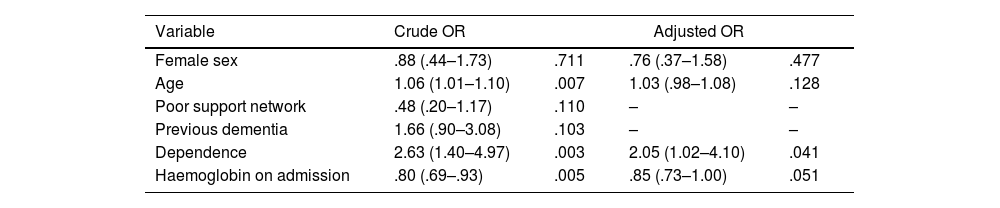

The factor related to functional loss with a statistically significant association was having some degree of previous dependency (OR=2.05 CI 95%=1.02–4.10, p=.041) (see Table 4).

Logistic regression for functional loss (n=84).

| Variable | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | .88 (.44–1.73) | .711 | .76 (.37–1.58) | .477 |

| Age | 1.06 (1.01–1.10) | .007 | 1.03 (.98–1.08) | .128 |

| Poor support network | .48 (.20–1.17) | .110 | – | – |

| Previous dementia | 1.66 (.90–3.08) | .103 | – | – |

| Dependence | 2.63 (1.40–4.97) | .003 | 2.05 (1.02–4.10) | .041 |

| Haemoglobin on admission | .80 (.69–.93) | .005 | .85 (.73–1.00) | .051 |

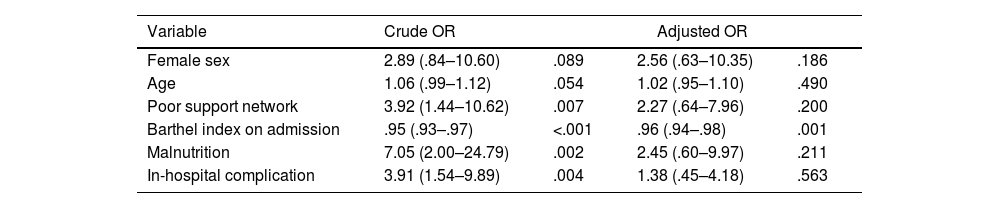

In those relating to institutionalization at one year, a statistically significant association was found with the Barthel index score at admission (OR=.96, CI 95%=.94–0.98, p=.001) (see Table 5).

Logistic regression for institutionalization (n=23).

| Variable | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 2.89 (.84–10.60) | .089 | 2.56 (.63–10.35) | .186 |

| Age | 1.06 (.99–1.12) | .054 | 1.02 (.95–1.10) | .490 |

| Poor support network | 3.92 (1.44–10.62) | .007 | 2.27 (.64–7.96) | .200 |

| Barthel index on admission | .95 (.93–.97) | <.001 | .96 (.94–.98) | .001 |

| Malnutrition | 7.05 (2.00–24.79) | .002 | 2.45 (.60–9.97) | .211 |

| In-hospital complication | 3.91 (1.54–9.89) | .004 | 1.38 (.45–4.18) | .563 |

Hip fractures are very common injuries in older adult patients and are associated with increased mortality, functional loss, and institutionalization. The characteristics of the subjects with hip fracture in the present study are similar to those reported in other publications.

In this study, in-hospital complications were detected in 50% of cases. In 2018, Venegas et al. reported a high frequency of in-hospital complications, similar to the data obtained in this study, also finding associated factors such as the presence of some degree of functional dependence, the need for supplemental oxygen in the postoperative period and the length of hospital stay.9

In the data obtained in this study, delirium was the most frequent complication, affecting 28.5% of the subjects who underwent surgery; different studies that have studied the subgroup of very elderly patients (over 85 or 90 years of age) show that they present more frequent in-hospital complications during hospitalization, as well as cognitive deterioration and malnutrition, in addition to greater need for red blood cell transfusion. These data coincide with those published in 2018 in the Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, where delirium is observed as the most frequent complication, being found in 59% of cases.9

In general, the available data suggest that delirium associated with hip fracture is an expression of greater biological vulnerability and clinical instability and deserves a thorough clinical assessment to be able to intervene in the medical conditions to prevent its appearance, as well as to identify acute conditions susceptible to treatment which, if not corrected, can lead to the patient's death.10,11

A high percentage of patients with femur fractures present preoperative anaemia, with a high incidence of blood transfusions and an increase in postoperative infections. Anaemia is a common factor in older adult patients and is associated with increased mortality.12 In elderly hip fracture patients, the presence of anaemia was associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality at 6 and 12 months after surgery.13 In another study Halm et al. found that higher haemoglobin levels were associated with lower odds of death when studying the effect of perioperative haemoglobin level in hip fracture patients.14 The results of this study are consistent with the literature in terms of the high incidence of blood transfusions during hospitalization, with the haemoglobin value at admission being a mean of 11.7 and transfusion requirement in 47% of subjects (p<.014).

One of the factors associated with mortality was moderate dependence, identified in 25% of the subjects analyzed. In a study published in 2017, Aranguren-Ruiz et al. found that the mortality/year ratio in patients who received surgical treatment for hip fracture was 15.6%, where one fifth of them had functional impairment for activities of daily living. They found that in patients with moderate to severe dependence, mortality was approximately 2 times higher per year than in non-dependent patients.10,15

Another factor associated with mortality found in the present study was malnutrition, present in 88.89% (p<.001), which is consistent with similar results found in the literature, where malnutrition has been reported to be associated with increased mortality. Vidal et al. evaluated the mortality rate one year after hip fracture surgery and found malnutrition as a cause of death in 18 of 130 patients.12,16 In another study published in 2010, it was found that 13 of 41 patients with malnutrition died during the first postoperative year, as well as establishing malnutrition as an important factor associated not only with mortality but also with loss of independence, impaired muscle function and decreased quality of life, so that current nutrition guidelines recommend nutritional supplements in elderly patients who are going to undergo surgery for hip fracture.

The present study found a significant association between older age and mortality (87 years on average), which is consistent with what has been previously described in other studies.10 In one study of 728 patients, 16% died within one year of surgery and showed that for each additional year of age, there was a 9.4% increase in the risk of dying within the same period of time after surgery.17

Of the subjects in this study, 61% were female and, as reviewed in several papers, the effect of this variable on mortality after hip surgery is debatable. Several studies evaluated mortality rates in hip fracture patients over a one-year period and found male sex to be a significant determinant of mortality.16,18 However, another study found no significant differences in mortality rates between the sexes, as is the case in this study.17,19

Some authors point out that health prior to the fracture and functional capacity have an impact on the prognosis of this type of patient.20,21 In a study published by Smith et al. it was found that the percentage of people with disability increased significantly in the 10 months prior to the hip fracture.22 This is why, as a secondary outcome, the loss of function was evaluated one year after the event, which occurred in 84 subjects (40%); on carrying out the multivariate analysis between loss of function and the independent variables, a statistically significant association was found with having previous dependence. This finding is consistent with the study published by Simanski et al. in 2002 which refers that, after multivariate analysis, a higher index on the Barthel scale before the fracture was related to a better functional prognosis in daily living activities.23 Three cohort studies of community-dwelling elderly assessed changes in functional status among respondents who fractured their hip compared to those who did not.24 They found that, over follow-up periods of 6 months to 6 years, hip fracture patients had greater functional loss with respect to activities of daily living than persons of the same age who had not fractured their hip.

Functional status around the time of hip fracture can be most accurately assessed by identifying patients when they are hospitalised.25,26 However, it is difficult to establish an adequate comparison without fractures as the demographic and health characteristics of patients differ from those of many other groups of older people.

Due to these results, a search was carried out in the literature to analyse this loss of functionality. The finding was that there are few studies which discuss it due to the heterogeneity of the patients, in addition to the lack of information on the functional state immediately before the hip fracture. Age is a determining factor in the loss of independence for activities,27 which in this study could be explained given that the average age was 87 years.

Another variable associated with functional loss is delirium, which has a negative influence on functional recovery. According to the results of this study it was the most frequent complication.

It has been seen that patients with dementia have a higher prevalence of osteoporosis and falls, estimating that between 20% and 40% present with hip fractures and consequently with greater dependence for daily living activities and worse ambulatory capacity.28 In general, in patients with dementia it has been seen that there is a greater risk of mortality, postoperative complications and longer hospitalizations.28 In this study, dementia accounted for more than half of the subjects analyzed (52.38%), which could explain the percentage of functional loss.

It has been described that between 15% and 30% of the subjects living at home at the time of the fracture require institutionalization1 In a study published in 2004, older age, increased comorbidity, dementia and decreased walking ability were found to be the main risk factors for institutionalization after hip fracture.1,29 In 2021, Velarde-Mayol et al. published a cohort in which 50% of subjects with hip fracture were institutionalized, and associated factors included greater dependency, cognitive impairment and subsequent readmissions prior to fracture.30 In this study the percentage of institutionalization at one year follow-up was 10.95%.

Similar to the results found in this study, integrated orthogeriatric care of the patient with fragility fracture of the hip improves both the quality of care and the clinical situation of the patients in the perioperative period, significantly reducing both hospital stay and mortality during admission.31

These findings must be understood within the limitations of the study design, one of which is that it was carried out in a single hospital centre. Furthermore, although orders were given at the time of discharge for outpatient follow-up and home rehabilitation, which forms part of the health system protocol in Colombia, these orders were not carried out homogeneously in all cases.

Despite the above, the present study has several strengths which include the methodology used, the longitudinal follow-up at one year in a Colombian cohort of octogenarian population, and a low percentage of loss to follow-up. In general terms, there is little literature available in the region, which represents an important gap in knowledge. Our findings therefore highlight possible factors that require intervention and attention in the assessment of hip fracture patients.

ConclusionsHip fracture is an acute condition that, together with the hospitalization it entails, involves a series of risks and complications in the older adult population, such as mortality, functional loss and a higher rate of institutionalization. The factors associated with higher mortality at one year were: an older age; the presence of malnutrition; moderate dependency prior to admission and in-hospital complications. With regard to functional loss and institutionalization, the cause was the presence of some degree of dependency prior to admission. Determining the factors involved in these outcomes is possible through a comprehensive geriatric assessment, which allows an early approach to identify and intervene to reduce risks, provides a better chance of recovery and has a greater impact on the prognosis of hip fractures in older adults.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence ii.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

FundingThe authors declare that they have received no funding for the conduct of the present research, the preparation of the article, or its publication.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.