Hip fractures constitute a capital public health issue associated with aging and frailty because of its impact on both quality of life and morbidity and mortality in older people. Fracture Liaison Services (FLS) have been proposed as tools to minimize this emergent problem.

Material and methodsA prospective observational study was conducted with 101 patients treated for hip fracture by the FLS of a regional hospital between October 2019 and June 2021 (20 months). Epidemiological, clinical, surgical and management variables were collected during admission and up to 30 days after discharge.

ResultsMean age of patients was 87.6±6.1 years and 77.2% were female. Some degree of cognitive impairment was detected at admission in 71.3% of patients using the Pfeiffer questionnaire, and 13.9% were nursing home residents, and 76.24% could walk independently before the fracture. Fractures were more commonly pertrochanteric (45.5%). Patients were receiving antiosteoporotic therapy in 10.9% of cases. The median surgical delay from admission was 26h (RIC 15–46h), the median length of stay was 6 days (RIC 3–9 days) and in-hospital mortality was 10.9%, and 19.8% at 30 days, with a readmission rate of 5%.

DiscussionPatients treated in our FLS at the beginning of its activity were similar to the general picture in our country in terms of age, sex, type of fracture, and proportion of patients treated surgically. A high mortality rate was observed, and low rates of pharmacological secondary prevention were followed at discharge. Clinical results of FLS implementation in regional hospitals should be assessed prospectively in order to decide their suitability.

Las fracturas de cadera constituyen un problema de salud pública capital asociado al envejecimiento y la fragilidad por su impacto en la calidad de vida y la morbimortalidad de las personas mayores. Se ha propuesto el uso de servicios de enlace de fracturas (FLS) para minimizar este problema emergente.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional prospectivo con 101 pacientes con fractura de cadera tratados en el FLS de un hospital regional entre octubre de 2019 y junio de 2021 (20 meses). Se recogieron variables epidemiológicas, clínicas y quirúrgicas durante el ingreso y hasta 30 días después del alta.

ResultadosLa edad media de los pacientes fue de 87,6±6,1 años, el 77,2% eran mujeres y el 71,3% tenían deterioro cognitivo al ingreso según el cuestionario de Pfeiffer. El 13,9% estaban institucionalizados y el 76,24% podían caminar de forma independiente antes de la fractura. Las fracturas fueron más frecuentemente pertrocantéricas (45,5%). Los pacientes recibían tratamiento antiosteoporótico en el 10,9% de los casos. La mediana de la demora quirúrgica desde el ingreso fue de 26 horas (RIC 15-46 horas), la mediana de la estancia fue de 6 días (RIC 3-9 días) y la mortalidad intrahospitalaria fue del 10,9%, y del 19,8% a los 30 días, con una tasa de reingreso del 5%.

DiscusiónLos pacientes tratados en nuestro FLS al inicio de su actividad eran similares a la imagen general de nuestro país en cuanto a edad, sexo, tipo de fractura y proporción de pacientes tratados quirúrgicamente. Se observó una alta tasa de mortalidad y se siguieron bajas tasas de osteoprotección al alta. Los resultados clínicos de la implantación del FLS en los hospitales regionales deben ser evaluados de forma prospectiva para decidir su idoneidad.

Hip fractures (HF) are one of the main health problems associated with aging and frailty because of its impact on both quality of life and morbimortality in the elderly, being an independent risk factor for mortality.1 Its estimated overall incidence in Spain is 104 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, which means some 45,000–50,000 hip fractures per year with an annual cost of 1591 million euros.2 It is predominantly found in elderly patients; 85.4% of all HF occur in those over 75 years of age and 2/3 in those over 80 years of age,3 and incidence surges to between 301 and 897 fractures per 100,000 people of 65 years or older.4 Women are three times more likely than men to suffer HF under 80 years, although the difference diminishes with increasing age due to senile osteoporosis.5,6 In Spain, 4.3% of patients die during the admission for HF, and 30% die during the first year after the fracture, while 50–60% of survivors do not recover their functional status.7,8

The underlying factor in most HF is osteoporosis, a decrease in bone density which leads to lower bone resistance to trauma, at the same time increasing the risk of instability and mechanical failure after surgery.7 HF patients have high rates of multi-morbidity, cognitive or functional impairment, nutritional issues, etc.,9–13 and medical complications are frequent in the postoperative period. Medical–surgical treatment is associated with fewer complications and mortality.14

In recent years Fracture Liaison Services (FLS) have been proposed to address the emerging public health issue which HF constitute. FLS are coordinator-based, multidisciplinary care units whose aims are to identify all patients with HF and ensure they receive the optimal inpatient therapy and secondary fracture prevention.15 These units have demonstrated their efficacy, reducing the occurrence of new fractures by 30–40% in a cost-effective manner for health systems.16 In Spain, FLS are being implemented as a means for reducing the impact HF have on the National Health Service, with coordination from the National Hip Fracture Registry (RNFC), which collects data from HF patients older than 75 years. In our Regional Hospital, an FLS was implemented in the second half of 2019. This study aims to describe the characteristics and outcomes of HF patients treated in our FLS, and explore which factors are related with death, readmission and length of stay in this population.

Material and methodsA prospective observational study was carried out, recruiting all patients over 75 years of age admitted for hip fracture in a first level care hospital with 141 beds between October 2019 and June 2021 (20 months). Patients admitted for this reason to the Traumatology ward who agreed to participate were included, after informed consent had been signed by them or their relatives in the case of patients with dementia. The only exclusion criterion was declining to participate. The data record came from the RNFC database to which our hospital center is attached and whose collection protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee with promoter code 2016_89 (RNFC). The investigators conducted the study in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Oviedo Convention. The study was developed in accordance with the protocol and in compliance with the standards of good clinical practice, as described in the International Conference on Harmonization standards for good clinical practice.

Epidemiological, clinical, surgical and management variables were collected during admission and 30 days after discharge. Fractures were classified from a prognostic and therapeutic point of view, distinguishing between intracapsular (biological problem, treated by arthroplasty or osteosynthesis with cannulated screws) and extracapsular (mechanical problem, treated with endomedullary nailing or sliding screw system). Statistical analysis was performed using R (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria, 2019) and RStudio (RStudio, Boston, MA, 2019). Categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequency. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile range (IQR) in case of presenting a non-Gaussian distribution. Factors related to death, readmission, surgical delay and hospital stay were studied using uni- and multivariable logistic and linear regression analyses, respectively. The relationship of these factors with the results was expressed in terms of odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval, or coefficients in the case of linear regression.

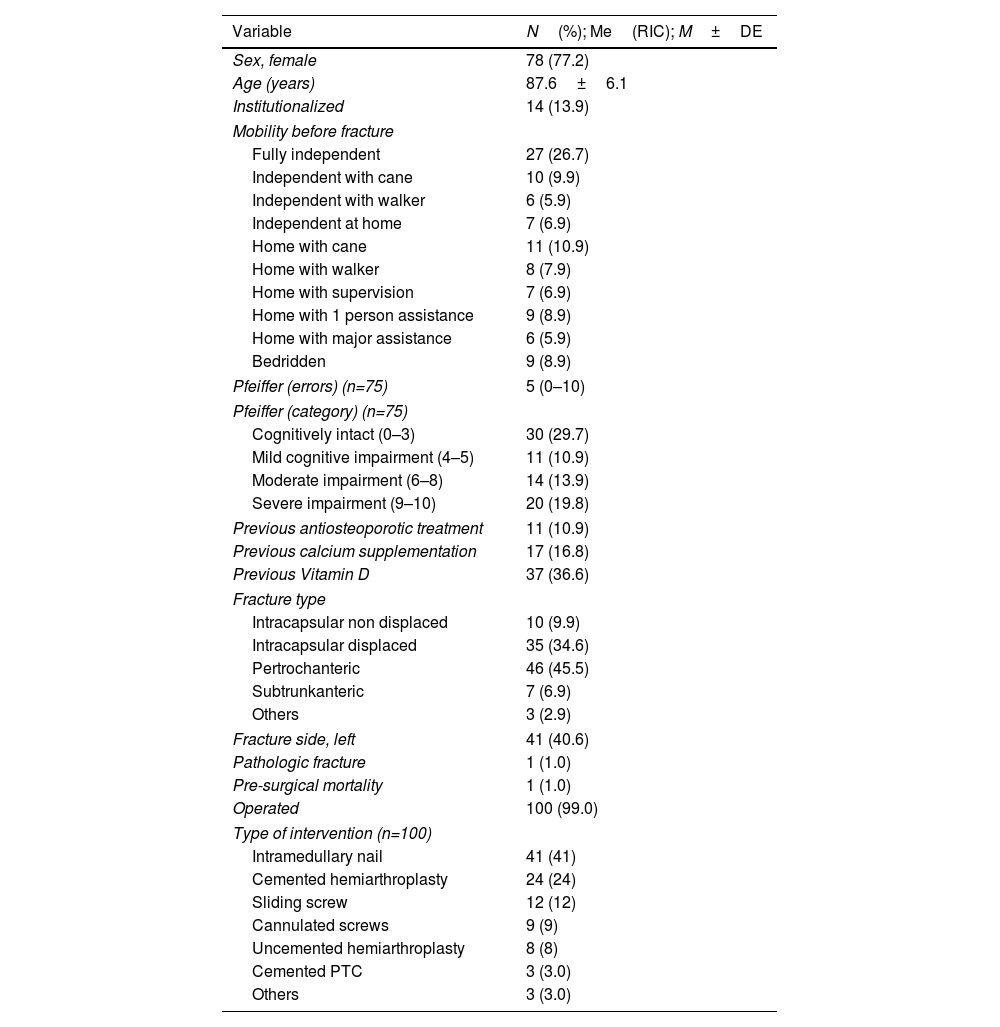

ResultsDuring the 20 months of the study, 101 patients with HF were admitted to our center (Table 1). The mean age was 87.6±6.1 years, with a clear predominance of women (77.2%). Some 13.9% were institutionalized before the fracture and 71.3% of the patients had some degree of cognitive impairment, as measured by the Pfeiffer questionnaire, yet 76.24% were independent for ambulation.

Baseline characteristics of patients hospitalized for hip fracture (n=101).

| Variable | N(%); Me(RIC); M±DE |

|---|---|

| Sex, female | 78 (77.2) |

| Age (years) | 87.6±6.1 |

| Institutionalized | 14 (13.9) |

| Mobility before fracture | |

| Fully independent | 27 (26.7) |

| Independent with cane | 10 (9.9) |

| Independent with walker | 6 (5.9) |

| Independent at home | 7 (6.9) |

| Home with cane | 11 (10.9) |

| Home with walker | 8 (7.9) |

| Home with supervision | 7 (6.9) |

| Home with 1 person assistance | 9 (8.9) |

| Home with major assistance | 6 (5.9) |

| Bedridden | 9 (8.9) |

| Pfeiffer (errors) (n=75) | 5 (0–10) |

| Pfeiffer (category) (n=75) | |

| Cognitively intact (0–3) | 30 (29.7) |

| Mild cognitive impairment (4–5) | 11 (10.9) |

| Moderate impairment (6–8) | 14 (13.9) |

| Severe impairment (9–10) | 20 (19.8) |

| Previous antiosteoporotic treatment | 11 (10.9) |

| Previous calcium supplementation | 17 (16.8) |

| Previous Vitamin D | 37 (36.6) |

| Fracture type | |

| Intracapsular non displaced | 10 (9.9) |

| Intracapsular displaced | 35 (34.6) |

| Pertrochanteric | 46 (45.5) |

| Subtrunkanteric | 7 (6.9) |

| Others | 3 (2.9) |

| Fracture side, left | 41 (40.6) |

| Pathologic fracture | 1 (1.0) |

| Pre-surgical mortality | 1 (1.0) |

| Operated | 100 (99.0) |

| Type of intervention (n=100) | |

| Intramedullary nail | 41 (41) |

| Cemented hemiarthroplasty | 24 (24) |

| Sliding screw | 12 (12) |

| Cannulated screws | 9 (9) |

| Uncemented hemiarthroplasty | 8 (8) |

| Cemented PTC | 3 (3.0) |

| Others | 3 (3.0) |

n: sample size; N: absolute frequency; Me: median; IQR: interquartile range; M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

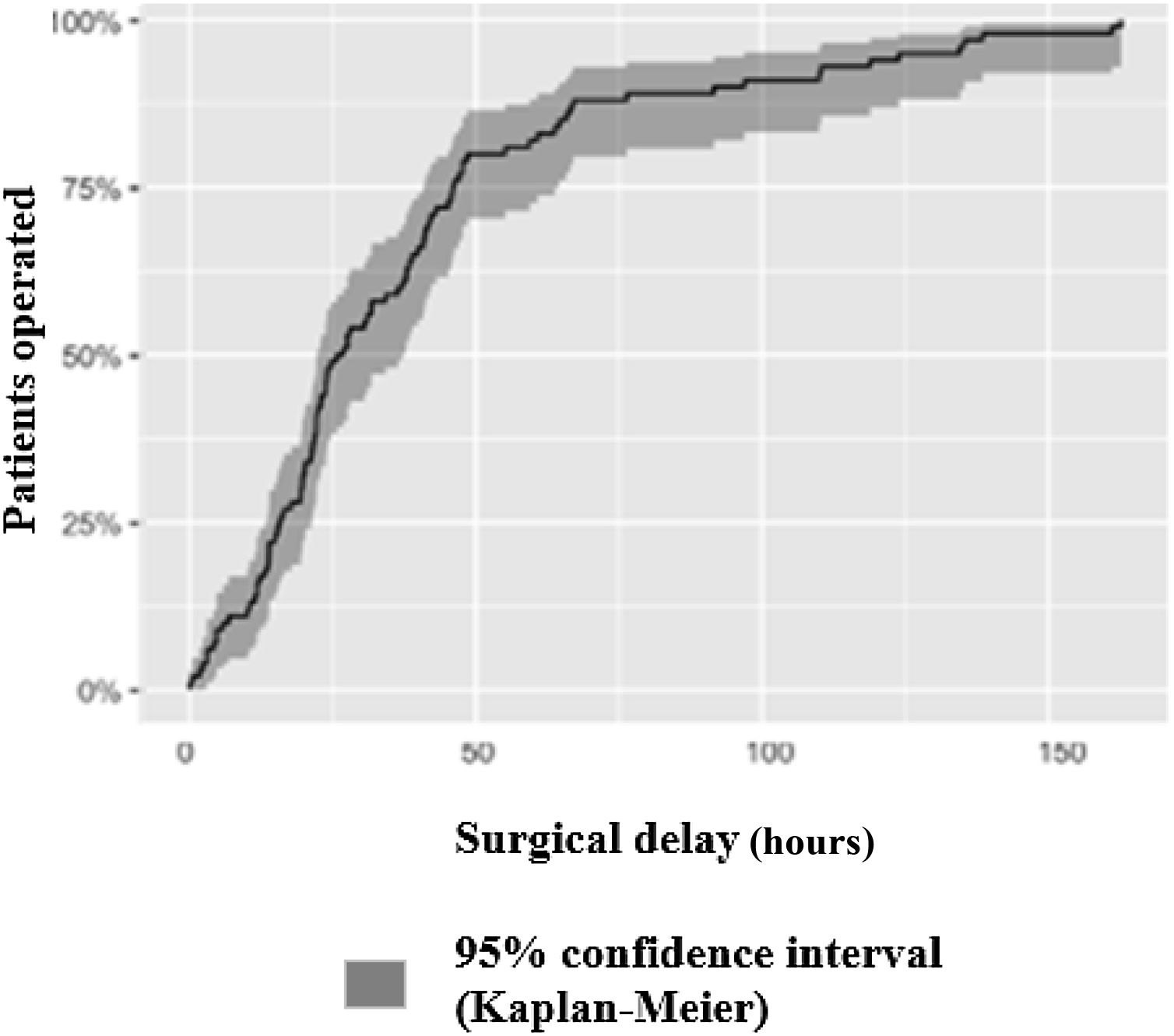

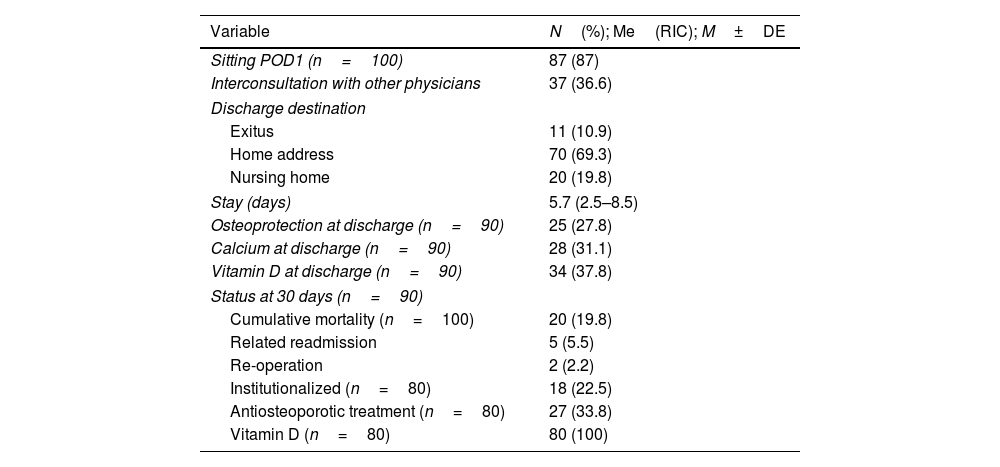

The most frequent type of fracture was pertrochanteric (46 cases, 45.5% of the total), followed by displaced intracapsular (34.6%), non-displaced intracapsular (9.9%), subtrochanteric (6.9%) and only 3 patients (3.0%) had atypical fractures. Only 10.9% of the patients were receiving antiosteoporotic therapies (resorption inhibitors and/or bone anabolics) at the time of the hip fracture. Of the 101 patients with fractures, 100 (99.0%) underwent surgery; only one patient did not undergo fracture repair because she died before surgery. The median surgical delay from admission (Fig. 1) was 26h (RIC 15–46h), with 79.0% of patients undergoing surgery within the guideline target of 48h from admission14,16,17 and all of them undergoing surgery under neuroaxial anesthesia. Eighty-seven percent of the patients were seated on the first postoperative day and the median stay was 6 days (RIC 3–9 days). Only 36.6% of patients benefited from comprehensive evaluation by Geriatrics or Internal Medicine and in-hospital mortality was 10.9%. At 30-day follow-up, mortality was 19.8%, while the readmission rate was 5% (2% due to surgery-related causes and 3% to medical causes). Regarding osteoporosis treatment, 27.8% of the patients were discharged with pharmacological secondary prevention treatment, while 33.8% of the patients who were still alive at 30 days were receiving it (Table 2).

Postoperative and post-discharge evolution (n=101).

| Variable | N(%); Me(RIC); M±DE |

|---|---|

| Sitting POD1 (n=100) | 87 (87) |

| Interconsultation with other physicians | 37 (36.6) |

| Discharge destination | |

| Exitus | 11 (10.9) |

| Home address | 70 (69.3) |

| Nursing home | 20 (19.8) |

| Stay (days) | 5.7 (2.5–8.5) |

| Osteoprotection at discharge (n=90) | 25 (27.8) |

| Calcium at discharge (n=90) | 28 (31.1) |

| Vitamin D at discharge (n=90) | 34 (37.8) |

| Status at 30 days (n=90) | |

| Cumulative mortality (n=100) | 20 (19.8) |

| Related readmission | 5 (5.5) |

| Re-operation | 2 (2.2) |

| Institutionalized (n=80) | 18 (22.5) |

| Antiosteoporotic treatment (n=80) | 27 (33.8) |

| Vitamin D (n=80) | 80 (100) |

n: sample size; N: absolute frequency; Me: median; IQR: interquartile range; M: mean; SD: standard deviation; POD1: first postoperative day.

None of the variables studied (sex, age, previous mobility, cognitive impairment, previous institutionalization, ASA surgical risk category, type of fracture, surgical delay) was significantly associated with in-hospital mortality or readmission. Regarding hospital stay, multivariate analysis found that institutionalized patients had significantly shorter stays (−2.3 days mean stay, 95%CI −1.2 to −3.6 days). Finally, no greater surgical delay was observed according to any of the aforementioned variables.

DiscussionEven in COVID-19 times, hip fractures continue to be an important cause of morbidity and mortality among older patients worldwide.18 It entails a high healthcare cost for health systems, both direct and indirect, as well as a significant decrease in health-related quality of life.19 In Europe, the incidence of fragility hip fracture is increasing mainly due to increased life expectancy.20 Patients who have a hip fracture are 86% more likely to experience a second fracture, generally in the first year after the index fracture,21 and 50% of all hip fractures occur in the 16% of the population who have already had a fracture previously. In spite of this, and inexplicably, less than 10% of patients who have suffered a hip fracture in Europe receive treatment with bisphosphonates. FLS are the most cost-effective model of approach to secondary fracture prevention and a good strategy for bridging this terrible therapeutic gap.22,23

Our sample consists mainly of women, very elderly, living in the community, with a high prevalence of cognitive impairment, but mostly independent before the HF. This is similar to what is reported for the Spanish population except for the unusually high rate of dementia.24 Mortality is also higher than usually reported in the literature,25–27 but at the time of the implementation of our FLS no Orthogeriatrics/Hospitalist comanagement program existed at our institution. Other FLS experiences have also failed to show mid-term benefits in mortality.28 Surgical management of fractures was almost universal, and 79% of patients were operated in the first 48h of admission, this being both a guideline recommendation15 and a marker of quality of care and early intervention being associated with a reduction in hospital stay.8,29

The rate of antiosteoporotic treatment was nonetheless low, with less than a third of patients receiving it at discharge, and only slightly more at 30 days. These rates are lower than observed in the RNFC, although this sample represents the first months of FLS activity, and continuous improvement is expected as the team gathers experience and revises its activity and results.29 In our region, Galicia, only another University Hospital (Clínico Universitario in Santiago de Compostela) and our Regional Hospital have International Osteoporosis Foundation certified FLS within the “Capture the Fracture” program. The degree of satisfaction of patients and professionals in these units is high, generating a collaborative environment conducive to promoting coordinated and prospectively evaluated teamwork.23

For all these reasons, and with all the clinical evidence available on the subject, implementing the FLS model and units with systematic shared care for the joint care of fractured patients from admission should be a priority at the present time, thus shortening hospital stay, reducing complications, minimizing functional deterioration and costs and above all improving mortality in the medium and long term.29

Limitations of the studyWe recognize that the study has certain limitations, since it is a single-center study, with a small sample size, carried out by a recently created FLS unit, in a Regional hospital, with a very aged target population and where it was not possible to include all the hip fractures due to reasons derived from the pandemic situation due to COVID-19. Although the sample size and follow-up time may be short, we believe that they are sufficient to establish conclusions, although modest, which are sufficiently solid and which may serve to stimulate other small hospitals to create similar units for the benefit of the patients they serve.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence ii.

FundingThe study was carried out without external funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the entire Traumatology Service of the Hospital Público de Monforte for their excellent willingness to collaborate in the recruitment of patients for our study and Dr. Romina González Vázquez for proofreading the text.

Rocío Arias Sanmiguel, Pamela Fernández Águila, Laura Ferreira Varela, María González Varela, Alberto Iglesias Seoane, Mónica Jacobo Castro, Alba Lobelle Seijas, Diana Lourido Mondelo, Noelia Rodríguez Sampayo