Return to sports (RTS) is maybe the main expectation for the patient after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). The aim of this study was to analyze the psychological readiness to RTS in a cohort of amateur sports after ACLR.

Material and methodsRetrospective study of a prospective database of patients treated with ACLR performed between January and December 2017. Psychological readiness to RTS after ACLR was evaluated with the short version of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Return to Sport After Injury (ACL-RSI) scale.

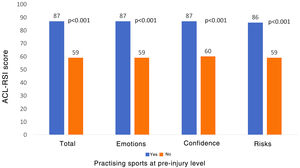

ResultsA total of 43 patients met the inclusion criteria. The mean age of the patients was 24.7 years. The mean follow-up was 32.5 months. All patients practiced any type of sports at final follow-up. The mean ACL-RSI score was 71.5. Fear of reinjury was mentioned by 14 patients (32.5%). Twenty-four patients (55.8%) pointed out that they did not practice sport at the pre-injury level. The mean ACL-RSI score was statistically significant lower in this group of patients (59.7 vs 87.3; p<.001).

ConclusionsFear of reinjury keeps after ACLR. Patients that they did not practice sport at the pre-injury level show lower scores in ACL-RSI for RTS.

La reincorporación deportiva es posiblemente el objetivo principal para el paciente tras la cirugía reconstructiva de ligamento cruzado anterior (LCA). El propósito del presente estudio fue determinar la preparación psicológica para la reincorporación deportiva de una cohorte de deportistas aficionados tratados mediante cirugía reconstructiva de LCA.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de una base de datos prospectiva de pacientes con rotura de LCA intervenidos entre enero y diciembre de 2017. La preparación psicológica del paciente para la reincorporación deportiva se valoró al final del seguimiento según la versión corta de la escala Anterior Cruciate Ligament Return to Sport After Injury (ACL-RSI).

ResultadosSe incluyeron en el estudio 43 pacientes con una edad media de 24,7años. El seguimiento medio de los pacientes fue de 32,5 meses. Todos los pacientes practicaban algún tipo de actividad deportiva al final del seguimiento. La puntuación media en la escala ACL-RSI fue de 71,5puntos. El miedo a lesionarse nuevamente al practicar deporte persistía en 14 pacientes (32,5%). Veinticuatro pacientes (55,8%) indicaron que no practicaban deporte al mismo nivel que antes de la lesión ligamentosa. La puntuación media en la escala ACL-RSI fue significativamente menor en este grupo de pacientes (59,7 vs. 87,3; p<0,001).

ConclusionesEl miedo a lesionarse nuevamente persiste tras la cirugía reconstructiva de LCA. Los pacientes que no practicaban deporte al mismo nivel que antes de la lesión ligamentosa presentaban menores puntuaciones en la escala ACL-RSI de preparación psicológica para la reincorporación deportiva.

Return to sports is possibly the main objective of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstructive surgery.1 Series published in the literature report a rate of between 33% and 95% at one year after surgery, and establish influencing factors such as age, type of graft used, level of sports activity, and type of sport.2,3 A satisfactory objective result is the first step towards a successful return to sports. Yet the improved evaluation questionnaires do not ensure a return to sport after surgery.4

Psychological factors have majorly influenced return to sports following ACL reconstruction. These factors include emotion-related dimensions such as fear of re-injury, confidence in performing at the same level, and appraisal of the risk of re-injury. Studies in the 1990s reported feelings of lack of confidence in patients who did not return to their pre-ACL tear sports activity.5,6 And more recent studies suggest a direct relationship of psychological factors with return to sports after ACL reconstruction.2,7–9

The purpose of the present study was to determine the psychological readiness for return to sports in a cohort of amateur athletes diagnosed with an ACL tear treated by reconstructive surgery. Our secondary objective was to study the psychological factors that most influenced return to sports. Our working hypothesis was that there would be a direct relationship between psychological factors and a return to sports in these patients.

Material and methodsStudy designRetrospective study of a prospective database of patients with ACL tears who underwent surgery between January and December 2017. The following inclusion criteria were established: age over 18 and under 40 years, no previous knee surgeries, minimum follow-up of 2 years. Exclusion criteria included age younger than 18 and older than 40 years, multi-ligamentous injury, ACL re-tear. All the patients gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

Surgical techniqueAll surgeries were performed by the same surgical team using anatomical reconstruction technique with 4 F, femoral anchorage with TightRope® system, and interference tibial screw (Arthrex, Naples, FL). Cartilage injuries were treated by debridement, if low grade, or drilling, if high grade, according to the Outerbridge classification10 (Outerbridge 1961). If meniscal injury was detected, it was treated by suturing or partial meniscectomy. In all cases, a single dose of 2g cefazolin was administered preoperatively as antibiotic prophylaxis. Suction drainage was not used. Intraoperative complications were recorded.

Postoperative managementThe postoperative recovery programme consisted of several phases with return to sports from the 6th month after surgery. Immediate partial weight bearing with crutches was allowed. A post-surgical knee extension brace was indicated for 4 weeks in patients with associated meniscal injury treated by suture. Return to sports was allowed if the patient had a symmetry index >90% in mobility, strength and hop tests.11

EvaluationsThe patients were evaluated preoperatively, at 6 months, at 1 year, and at the end of follow-up by Tegner and Lysholm,12 Lysholm and Gillquist,13 VAS, and IKDC Subjective and Clinical Evaluation scores.14 Clinical significance was also assessed using the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the Tegner (one point),15 Lysholm (8.9 points),15 and subjective IKDC (16.7 points)16 scores; and patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) for the subjective IKDC score (75.9 points).17

The patient's psychological readiness for return to sports was assessed at the end of follow-up according to the short version of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Return to Sport after Injury (ACL-RSI) scale.8 The scale consists of 6 questions that measure three psychological dimensions related to return to sports after injury: emotions (questions 1-2-3), confidence (questions 4–5), and risk appraisal (question 6); with a maximum score of 100 points. The higher the score, the higher the psychological readiness for a return to sports. The scale was translated from English into Spanish by two bilingual Spanish orthopaedic surgeons.

Medical and surgical complications, hospital readmissions in the first 30 days after surgery, tendon re-tears, and the need for re-operation were recorded.

At the end of follow-up, return to sports and level of sporting activity were recorded according to Tegner score.12 And the patients answered the question according to whether they were practising sport at pre-injury level.

Statistical analysisSPSS® version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. P-values equal to or less than .05 were considered significant. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine normal distribution. Student's t-tests were used to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 test for variables with normal distribution. Pearson's test was used to analyse the relationship between continuous variables. A factor analysis was undertaken using a data reduction technique to determine which section and psychological dimension of the ACL-RSI scale most influenced a return to sports at pre-injury level. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure (KMO=.906) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (p<.001) were applied prior to the factor analysis, to verify the adequacy of the data.

The subsequent power analysis of the study to detect a 10-point difference on the ACL-RSI scale between patients who were practising sports at pre-ligament injury level and those who were not, with the sample size, a bilateral approach, and 95% confidence interval, resulted in a power for the study of 88.5%.

ResultsGeneral data of the seriesForty-three patients met the inclusion criteria over the study period.

The mean age was 24.7 years (CI 95%: 22.2–27.5), mean BMI was 25.1 (95% CI: 23.9–26.1), predominance of males of 88.4% (38 patients), and of the left side of 58.1% (25 patients).

Football was the main sport in 30 patients (69.7%), followed by rugby in 5 (11.6%), running in 5 (11.6%), and basketball in 3 (8.1%); with a mean Tegner score of 6.4.

The mean time to surgery was 4.9 weeks (95% CI: 8.1–11.5).

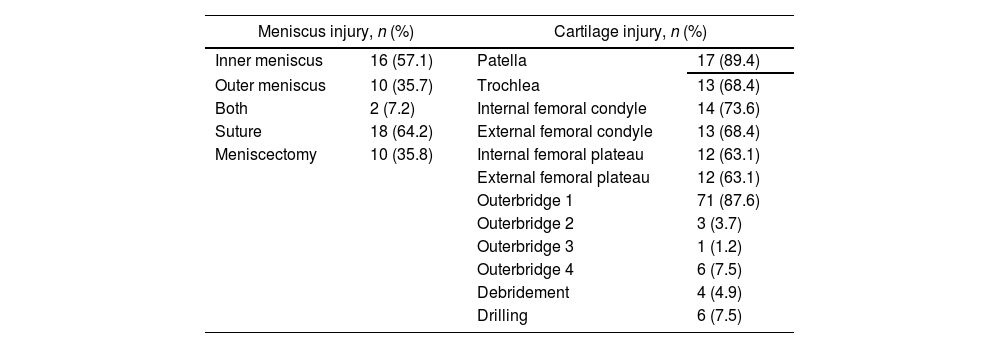

Intraoperative dataACL tear was confirmed in all the patients during surgery. Associated meniscal injury was detected in 28 patients (65.1%) and associated cartilage injury in 19 patients (44.2%). Cartilage injuries were grade 1 in 87.6%. Table 1 shows the location and grade of the injuries, and the procedures performed. No intraoperative complications were recorded.

Intraoperative findings and procedures.

| Meniscus injury, n (%) | Cartilage injury, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inner meniscus | 16 (57.1) | Patella | 17 (89.4) |

| Outer meniscus | 10 (35.7) | Trochlea | 13 (68.4) |

| Both | 2 (7.2) | Internal femoral condyle | 14 (73.6) |

| Suture | 18 (64.2) | External femoral condyle | 13 (68.4) |

| Meniscectomy | 10 (35.8) | Internal femoral plateau | 12 (63.1) |

| External femoral plateau | 12 (63.1) | ||

| Outerbridge 1 | 71 (87.6) | ||

| Outerbridge 2 | 3 (3.7) | ||

| Outerbridge 3 | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Outerbridge 4 | 6 (7.5) | ||

| Debridement | 4 (4.9) | ||

| Drilling | 6 (7.5) | ||

The mean follow-up was 32.5 months (95% CI: 31.7–33.5).

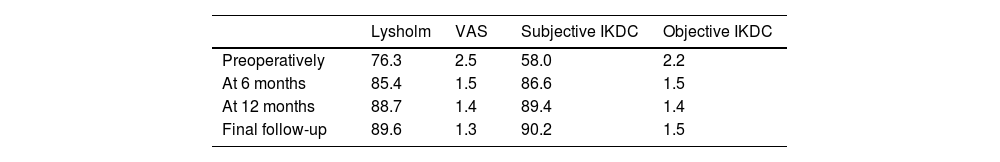

Clinical rating scores improved from the preoperative evaluation to the last revision, with significant differences in Lysholm score (p=.03), IKDC for subjective (p<.001) and objective (p=.03) evaluation; but not in VAS score (p=.12) (Table 2). The mean increase from preoperative evaluation and last revision was 12.3 (95% CI 11.2–14) on the Lysholm scale; 34.8 (95% CI 25.8–43.8) on the subjective IKDC, and −.92 (95% CI −.13 to −1.72) on the VAS scale. In terms of clinical significance, the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was reached in 88.3% (38 patients) in Lysholm score, 100% (43 patients) in IKDC score, but only 11.6% (5 patients) in Tegner score. A total of 93% (40 patients) reached patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) in subjective IKDC score.

There were no postoperative complications, hospital readmissions in the first 30 days after surgery, tendon re-tears, or requirement for reoperation.

Psychological preparationThe mean ACL-RSI score was 71.5 points at the end of follow-up.

In terms of the dimensions of emotions, confidence, and risk appraisal, the mean score was 71.7, 71.6, and 70.9, respectively. A total of 32.5% (14 patients) reported that they had a fear of re-injury in their sport.

No significant differences were detected in the mean ACL-RSI score in terms of sex (males 71.8 vs. females 69.1; p=.9), presence of meniscal injury (67.9 vs. 78.2; p=.13). No significant correlation was detected with respect to age (r=.084; p=.59), or time to surgery (r=−.75; p=.63).

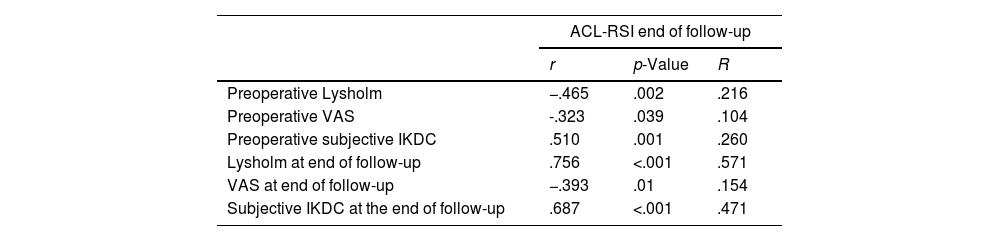

A significant correlation was observed between the ACL-RSI and the functional assessment scores both preoperatively and at the end of follow-up (Table 3).

Correlations between ACL-RSI and functional assessment scores preoperatively and at the end of follow-up.

| ACL-RSI end of follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| r | p-Value | R | |

| Preoperative Lysholm | −.465 | .002 | .216 |

| Preoperative VAS | -.323 | .039 | .104 |

| Preoperative subjective IKDC | .510 | .001 | .260 |

| Lysholm at end of follow-up | .756 | <.001 | .571 |

| VAS at end of follow-up | −.393 | .01 | .154 |

| Subjective IKDC at the end of follow-up | .687 | <.001 | .471 |

ACL-RSI: Anterior Cruciate Ligament Return to Sport After Injury; R: coefficient of determination; r: Pearson's correlation coefficient.

The mean sports activity level according to Tegner score decreased to 6.2 (p=.47) at the end of follow-up. All the patients were practising some kind of sport at the end of follow-up. In 29 patients (67.4%) there was a change in their level of sport activity according to the Tegner scale. Sixteen of them had gone down in level (8 one level, 5 two levels, and 3 three levels) and 13 up (8 one level, 5 two levels).

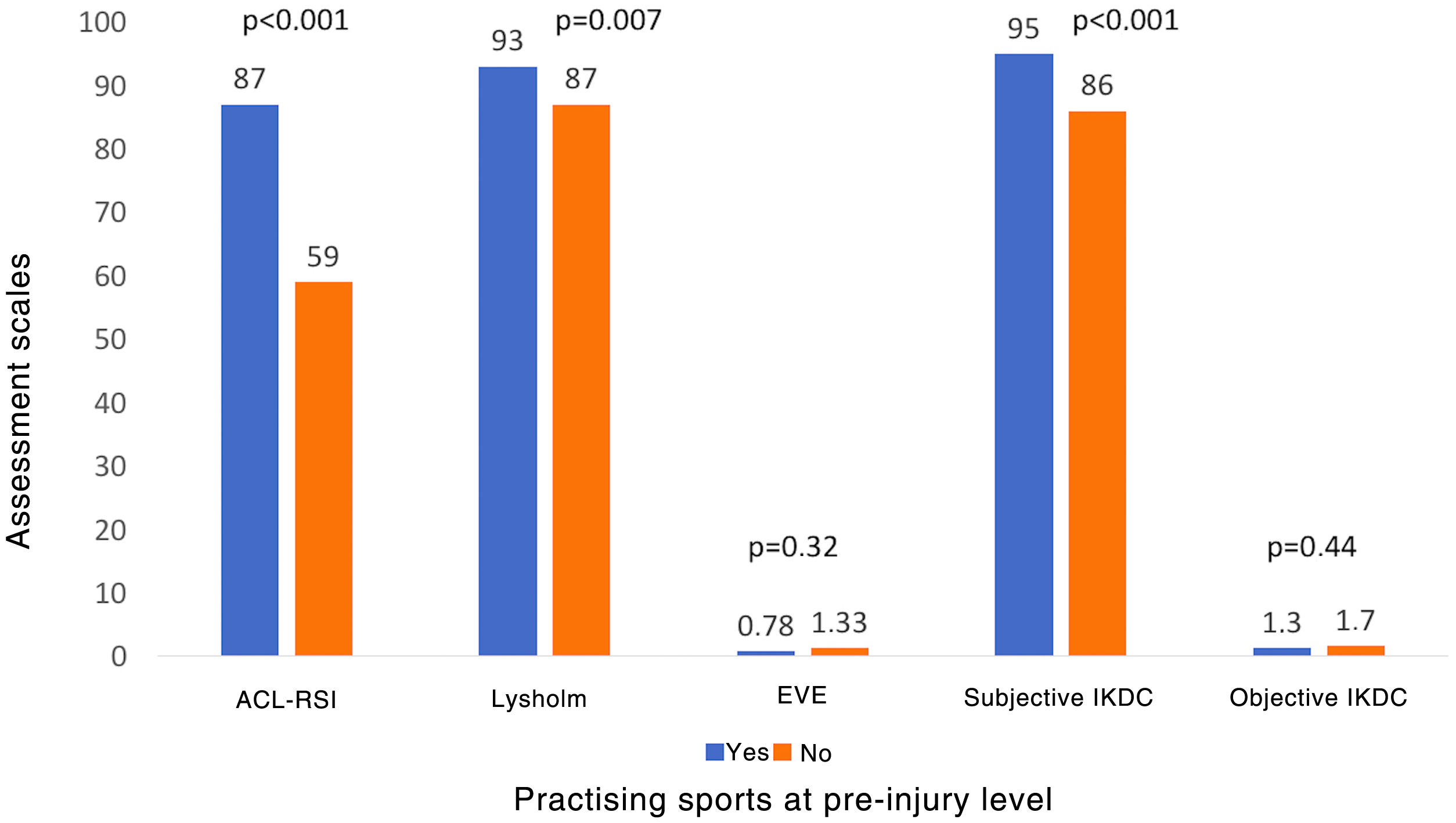

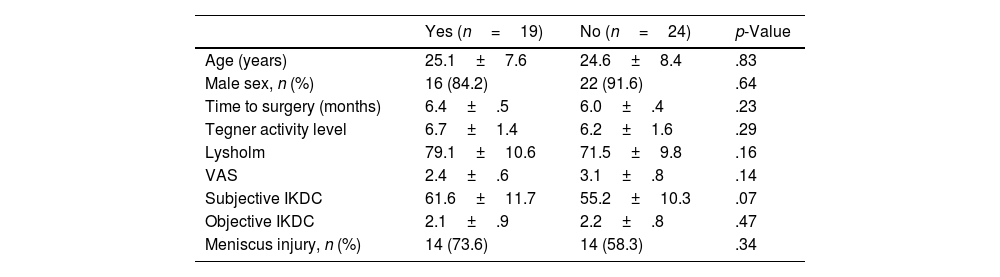

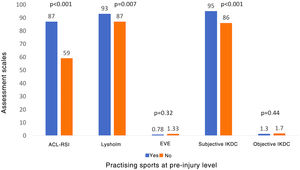

Twenty-four patients (55.8%) reported that they were not playing sports at pre-injury level. Statistical analysis with the variable practising sport at pre-injury level at the end of follow-up as an independent variable detected no significant differences in age (p=.83), sex (p=.64), time to surgery (p=.23), preoperative sports activity level (p=.29), Lysholm scale (p=.16), VAS (p=.14), IKDC form for preoperative subjective (p=.07) and objective (p=.47) evaluations, or the presence of associated meniscal injury (p=.34) (Table 4). At the end of follow-up, the patients who were not playing sports at pre-injury level had lower mean Lysholm scores (87.0 vs. 93.0; p=.007), higher mean scores on the VAS scale (1.33 vs. .78; p=.32), a lower mean score on the IKDC form for subjective evaluation (86.6 vs. 95.0; p<.001), and a higher mean score for objective evaluation (1.7 vs. 1.3, p=.44) (Fig. 1). Regarding clinical significance, the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was not reached in 20.8% (5 patients) on the Lysholm scale, or in patient-acceptable symptom state (PASS) score on the subjective IKDC scale in 8.3% (2 patients).

Practising sports at pre-injury level and preoperative variables.

| Yes (n=19) | No (n=24) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 25.1±7.6 | 24.6±8.4 | .83 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 16 (84.2) | 22 (91.6) | .64 |

| Time to surgery (months) | 6.4±.5 | 6.0±.4 | .23 |

| Tegner activity level | 6.7±1.4 | 6.2±1.6 | .29 |

| Lysholm | 79.1±10.6 | 71.5±9.8 | .16 |

| VAS | 2.4±.6 | 3.1±.8 | .14 |

| Subjective IKDC | 61.6±11.7 | 55.2±10.3 | .07 |

| Objective IKDC | 2.1±.9 | 2.2±.8 | .47 |

| Meniscus injury, n (%) | 14 (73.6) | 14 (58.3) | .34 |

Mean±standard deviation.

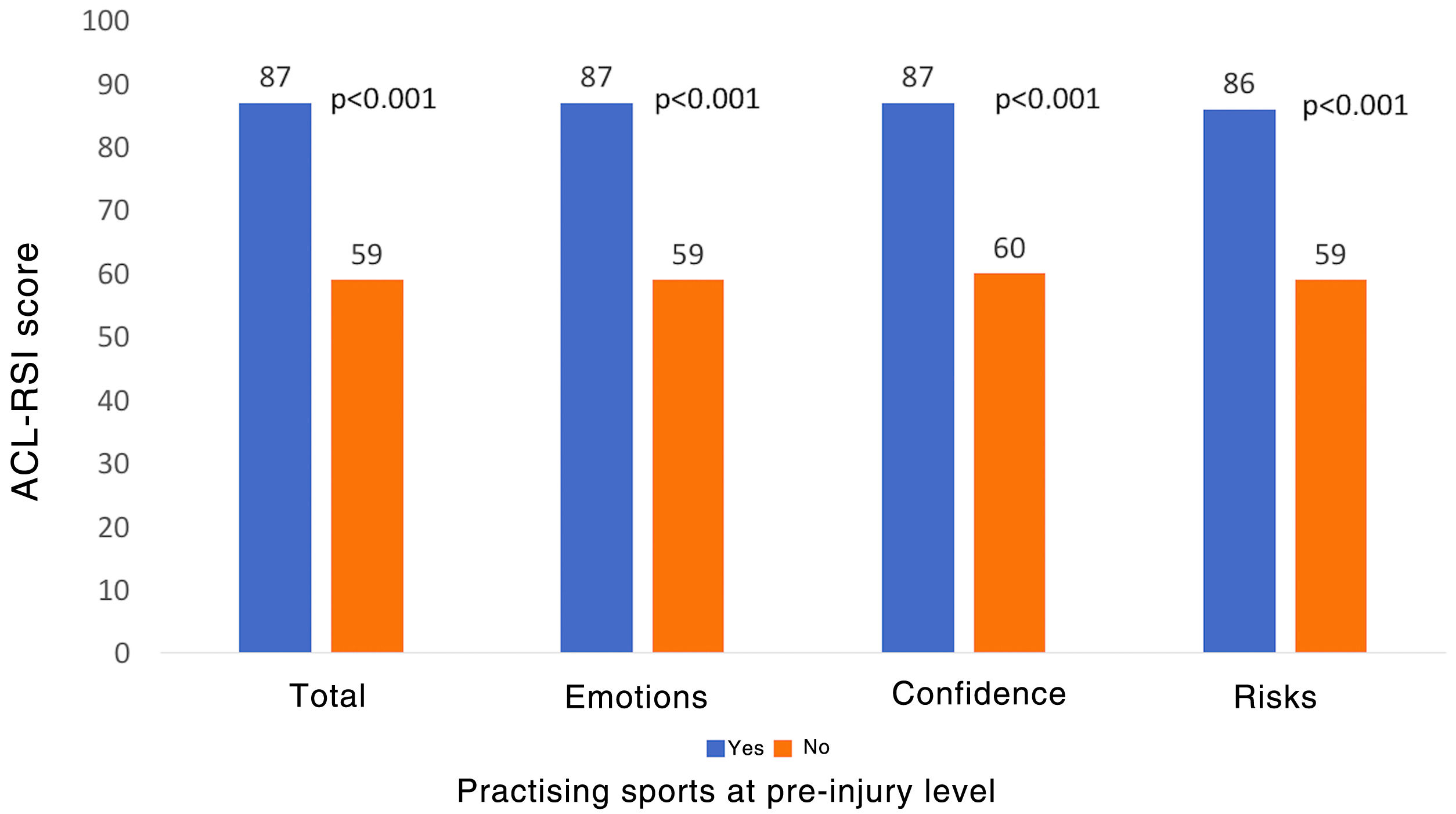

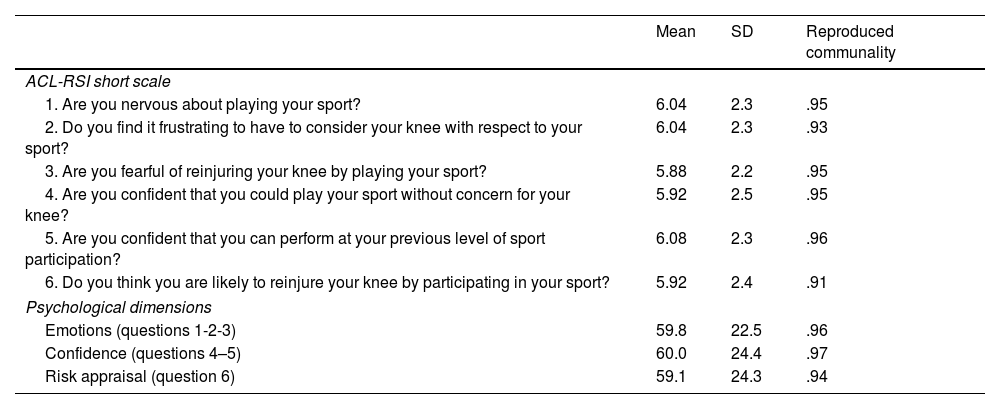

The mean ACL-RSI score was also lower in the patients who were not practising sports at pre-injury level (59.7 vs. 87.3; p<.001). And likewise, when determining each of the psychological dimensions: emotions (59.8 vs. 87.5; p<.001), confidence (60.0 vs. 87.2; p<.001), and risk appraisal (59.1 vs. 86.6; p<.001) (Fig. 2). Of the patients who feared re-injury, 92.8% were not practising sports at pre-injury level vs. 41.3% of those who did not fear re-injury (p=.001). When factor analysis was performed in the subgroup of patients who were not practising sports at pre-injury level, all the items accounted for more than 90% of the variability contained in the data (Table 5). The correlation between the items of the ACL-RSI scale was high (r>.89; p<.001).

Factor analysis of the ACL-RSI scale questions and psychological dimensions in patients who had not returned to sports at pre-injury level.

| Mean | SD | Reproduced communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACL-RSI short scale | |||

| 1. Are you nervous about playing your sport? | 6.04 | 2.3 | .95 |

| 2. Do you find it frustrating to have to consider your knee with respect to your sport? | 6.04 | 2.3 | .93 |

| 3. Are you fearful of reinjuring your knee by playing your sport? | 5.88 | 2.2 | .95 |

| 4. Are you confident that you could play your sport without concern for your knee? | 5.92 | 2.5 | .95 |

| 5. Are you confident that you can perform at your previous level of sport participation? | 6.08 | 2.3 | .96 |

| 6. Do you think you are likely to reinjure your knee by participating in your sport? | 5.92 | 2.4 | .91 |

| Psychological dimensions | |||

| Emotions (questions 1-2-3) | 59.8 | 22.5 | .96 |

| Confidence (questions 4–5) | 60.0 | 24.4 | .97 |

| Risk appraisal (question 6) | 59.1 | 24.3 | .94 |

ACL-RSI: Anterior Cruciate Ligament Return to Sport After Injury; SD: standard deviation.

The most important findings of our study were: (1) 55.8% of the patients were not practising sports at pre-injury level, (2) the patients were not playing sports at pre-injury levels had significantly lower ACL-RSI scores at the end of follow-up, (3) 32.5% of the patients reported that they feared re-injury when playing their sport, and (4) all items and dimensions of the ACL-RSI scale had a similar influence on return to sports.

The patients displayed elevated expectations for a quick recovery and return to sport after ACL tear. However, not all patients will return to their previous level of sports activity, despite satisfactory results on the evaluation scales.2,3

Previous studies have examined the influence of psychological factors on return to sports following ACL tear.18 Sonesson et al. assessed expectations, satisfaction, and motivation using the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form (IKDC-SKF) in 65 patients with ACL tear preoperatively, and at 16, and 52 weeks postoperatively. They concluded that patients with higher motivation values preoperatively and at 16 weeks postoperatively had returned to their sports activity at pre-injury level by 52 weeks postoperatively.19 Baez et al. reported that each point increase on the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia-11 (TSK-11) was 17% more likely to result in a return to sports at pre-ACL tear levels in their study of 40 patients with a one-year follow-up.20 Christino et al. analysed level of self-esteem using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 27 patients at a mean follow-up of 16 months, and concluded that the score was significantly higher in those who had returned to their previous sports activity, and with no differences with respect to the objective assessment.21 Nwachukwu et al. published a recent systematic review including 19 studies with 2175 patients and indicated that psychological factors had a direct relationship with return to sports at pre-ACL surgery level.7 In our study, a high correlation (r>.7) was observed between the ACL-RSI score and the subjective Lysholm and IKDC scores at the end of follow-up. In fact, the patients who were not playing sport at pre-injury level had significantly lower ACL-RSI, Lysholm, and subjective IKDC scores at the end of follow-up. However, this mean difference of 6 points on the Lysholm scale and 8.4 points on the subjective IKDC was less than the value indicated for clinical significance by the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) score.15,16 Gobbi et al. found no significant differences between the patients who had returned to sports activity and those who had not on the Lysholm and IKDC scales, and concluded that these scales do not discriminate between the two groups of patients,22 while the ACL-RSI scale does.

Fear of re-injury is the psychological factor most frequently reported by patients after ACL surgery. Nwachukwu et al. report that 76.7% of patients mentioned this as the main reason for not returning to their pre-injury sports activity in 13 studies involving 394 patients.7 And Lentz et al. in 51.8% in 27 patients.4 According to our results, 58.3% of the patients indicated it as the reason for not practising sport at pre-injury level.

Return to sports is between 33% and 95% one year after surgery according to published series. DeFazio et al. recently published a systematic review of 1738 patients who underwent ACL hamstring tendon autograft, with a return to sports rate of 70.6%, and return at pre-injury level of 48.5%.3 And Nwachukwu et al. reported in 19 studies with 2175 patients analysing the influence of psychological factors on return to sports, that the sports return rate was 63.4%, and in 15 studies with 1494 patients, 64.4% returned to sports activity at pre-injury level.7 In our study, all the patients were practising some kind of sport at the end of follow-up, although only 44.2% reported practising sport at pre-injury level.

Our study has certain limitations. Firstly, the sample size, despite a subsequent statistical power that could be considered good. Secondly, we did not assess postoperative joint stability with a validated arthrometer. Thirdly, the ACL-RSI scale for psychological assessment has not been validated in Spanish. Fourthly, we did not collect a history of previous sports injuries, which might influence the final result. However, it also has strengths. It is a prospective study, with evaluation questionnaires of statistical and clinical significance, applied to all patients, and with no loss to follow-up. And it contributes to the analysis of psychological factors in return to sports in patients following ACL reconstruction.

ConclusionFear of re-injury persists after ACL reconstructive surgery. The patients who did not play sports at pre-injury level have lower ACL-RSI scores for psychological readiness for return to sports. Our findings may guide future studies on psychological factors influencing return to sports following ACL reconstruction surgery.

FundingNo financial or other support was received for this study, in whole or in part.

Level of evidenceLevel iv study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.