Topical tranexamic acid (TXA) has been shown to decrease blood loss in knee and hip arthroplasty. Despite there is evidence about its effectiveness when administered intravenous, its effectiveness and optimal dose when used topically have not been established. We hypothesised that the use of 1.5g (30mL) of topical TXA could decrease the amount of blood loss in patients after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA).

Material and methodsOne hundred and seventy-seven patients receiving a RSTA for arthropathy or fracture were retrospectively reviewed. Preoperative-to-postoperative change in haemoglobin (ΔHb) and hematocrit (ΔHct) level drain volume output, length of stay and complications were evaluated for each patient.

ResultsPatients receiving TXA has significant less drain output in both for arthropathy (ARSA) (104 vs. 195mL, p=0.004) and fracture (FRSA) (47 vs. 79mL, p=0.01). Systemic blood loss was slightly lower in TXA group, but this was not statistically significant (ARSA, ΔHb 1.67 vs. 1.90mg/dL, FRSA 2.61 vs. 2.7mg/dL, p=0.79). This was also observed in hospital length of stay (ARSA 2.0 vs. 2.3 days, p=0.34; 2.3 vs. 2.5, p=0.56) and need of transfusion (0% AIHE; AIHF 5% vs. 7%, p=0.66). Patients operated for a fracture had a higher rate of complications (7% vs. 15.6%, p=0.04). There were no adverse events related to TXA administration.

ConclusionTopical use of 1.5g of TXA decreases blood loss, especially on the surgical site without associated complications. Thus, haematoma decrease could avoid the systematic use of postoperative drains after reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

El ácido tranexámico (ATX) tópico ha demostrado disminuir de forma significativa el sangrado en artroplastia de cadera y rodilla. A pesar de que en la artroplastia de hombro la mayoría de trabajos han demostrado su eficacia por vía intravenosa, la eficacia y dosis por vía tópica aún no está determinada. El objetivo fue comprobar si 1,5g de ATX en bajo volumen (30ml) administrado de manera tópica disminuiría el sangrado tras la artroplastia invertida de hombro (AIH).

Material y métodosSe revisaron de manera retrospectiva 177 pacientes consecutivos intervenidos de AIH por artropatía y fractura. Se recogieron datos de ΔHb y ΔHto a las 24h, débito del drenaje (ml), estancia media y complicaciones.

ResultadosLos pacientes que recibieron ATX presentaron menor débito del drenaje tanto en artroplastia electiva (AIHE) (104 vs. 195ml; p=0,004) como por fractura (AIHF) (47 vs. 79ml; p=0,01). Aunque fue ligeramente menor en el grupo de ATX, no se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en el sangrado sistémico (AIHE ΔHb 1,67 vs. 1,90mg/dl, AIHF 2,61 vs. 2,7mg/dl; p=0,79), estancia media (AIHE 2,0 vs. 2,3 días, p=0,34; 2,3 vs. 2,5, p=0,56) o necesidad de transfusión (0% en AIHE; AIHF 5 vs. 7%; p=0,66). Los pacientes intervenidos por fractura presentaron mayor tasa de complicaciones que aquellos que lo hicieron por artropatía (7 vs. 15,6%; p=0,04). No se observaron complicaciones asociadas al uso de ATX.

ConclusiónLa administración tópica de 1,5g de ATX reduce el sangrado de manera significativa en el sitio quirúrgico, sin observarse complicaciones asociadas. La disminución del hematoma posquirúrgico permitiría evitar el uso sistemático de drenajes posquirúrgicos.

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is an antifibrinolytic agent that functions as a competitive inhibitor with lysine by blocking its binding to plasminogen molecules. It is currently a widely used drug that has been shown to be safe and cost-effective in hip and knee arthroplasty in terms of decreased systemic bleeding, fewer transfusions and reduced drainage debit.1,2 It is a well-tolerated drug with few side effects; the most common are digestive (nausea or diarrhoea) and, in exceptional cases, seizures in patients with a history of high doses or allergy to the drug. There is concern about the potential increased risk of thromboembolic events following intravenous administration, although recent studies have demonstrated its safety and efficacy regardless of the individual patient's risk of death, not only in the field of orthopaedics but also in other surgical fields.3

Despite the current evidence in favour of the use of TXA in knee and hip arthroplasty, there is still reluctance to use it in patients with a history of thromboembolism or concomitant renal pathology and the optimal dose and route of administration is not yet established.2 The use of the topical route has proven to be as effective as intravenous administration in hip and knee arthroplasty. Typically, between 1 and 3g of TXA is administered topically before closure, alone or in combination with saline (SSF) and sometimes other drugs such as local anaesthetic, corticosteroid, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or antibiotic, and has been shown to reduce postoperative bleeding in different joints, including the shoulder.4

The rate of transfusion in shoulder arthroplasty varies in the literature, from less than 1% in selected cohorts to 43%.5,6 As recently as 2015, the first study analysing TXA in shoulder arthroplasty evaluated its efficacy when administered topically.4 Other authors have subsequently demonstrated the efficacy of TXA in shoulder arthroplasty with different intravenous doses when compared with placebo.7–11

The reduction in bleeding would allow a reduction in the number of transfusions, with a decrease in infections, allergic reactions and other associated complications. In addition, less bleeding could avoid the systematic use of drains, so that TXA could help to improve and facilitate perioperative patient management.

The aim of the study is to determine whether 1.5g of TXA in a low volume solution (30mL) would reduce bleeding in patients undergoing reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA).

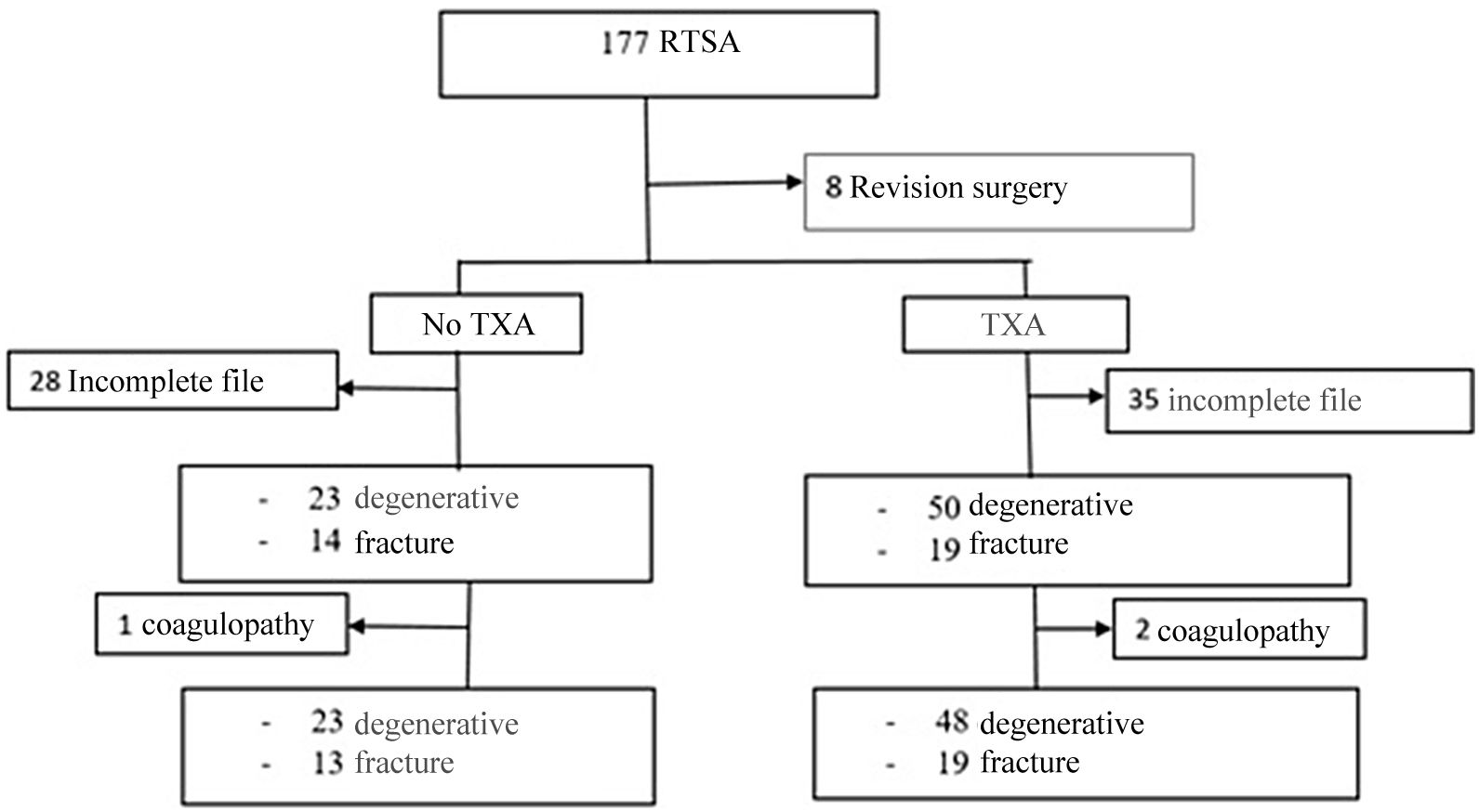

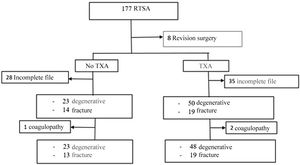

Material and methodsA retrospective observational cohort study was designed to review patients undergoing primary RTSA of the shoulder between January 2013 and March 2020; cohorts were established according to whether they had received TXA or not. Hospital ethics committee approval was obtained (PI-4267). Inclusion criteria were patients undergoing primary RTSA surgery. Revision surgeries or tumour surgeries were excluded, so after reviewing 177 arthroplasties a sample of 169 patients was obtained.

Demographic data were collected, as well as the existence of comorbidities, preoperative risk according to the American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) scale, the reason for surgery, hospital stay, haemoglobin (Hb) and haematocrit (Hto) pre-surgery and 24h after surgery, as well as drain debit – in patients in whom it was placed – and immediate postoperative complications.

A total of 63 patients (35 in the TXA group) were excluded due to incomplete clinical history (no blood tests at 24h or drainage volume in millilitres [mL]). Finally, 106 patients were included with a mean age of 76.3±7.5 years, of whom 85% (90 patients) were women.

All patients were operated using interscalene block and general anaesthesia. With the patient in a beach chair, a deltopectoral approach was performed, using the same implant and surgical technique in all cases. The administration of TXA was performed according to the surgeon's preference, although it was observed that with familiarisation with its use there was an increasing trend over the years since until 2015 it was used in less than 50% of cases to, from 2017, administer it to more than 70–80% of patients. The administration pattern was local injection of 1.5g of TXA in deep and superficial planes before closure. Each .5g ampoule has a volume of 10mL for a total injection volume of 30mL. The drain was placed intra-articularly, kept closed for 2h and removed at 24h.

Patients on anticoagulant therapy (warfarin) were discontinued and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) was administered every 12h as indicated by the anaesthesia department. Patients on acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) 100mg did not change their regimen. Transfusion was indicated in cases where Hb was ≤7g/dL or presented symptoms of anaemia (tachycardia, hypotension, etc.).

The primary study variable was the variation of post-surgical Hb (ΔHb) and Hto (ΔHto). Secondary variables were drainage debit (mL), hospitalisation time (days after surgery) and occurrence of complications in the first 6 months postoperatively.

Data were analysed using SPSS (version 21.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL). The χ2 test was used to contrast the proportions of the variables. The normal distribution of quantitative variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The ANOVA test and the Mann–Whitney test for non-parametric variables were used to compare the means of normally distributed variables.

Statistically significant differences were considered to be those in which p was <.05.

ResultsA first analysis was performed to determine which preoperative characteristics could be associated with an increased risk of bleeding. Patients undergoing elective surgery had less bleeding than patients undergoing surgery for fractures of the proximal humerus (FPH) (ΔHb 1.50 vs. 2.14g/dL, p=0.032; ΔHto 5.00% vs. 6.53%, p=.034), so separate groups were established according to the preoperative diagnosis: 73 patients were operated for arthropathy and 33 corresponded to the fracture group.

It was also observed that 3 patients had coagulopathies previously assessed by the haematology service: 2 patients had idiopathic thrombocytopenia and another patient had lupus anticoagulant. This group of patients presented higher bleeding (ΔHb 3.9 vs. 1.9g/dL, p=.001; ΔHto 11.87 vs. 6.14%, p=.003) and were excluded. Of these patients, one patient underwent RTSA for fracture and required postoperative transfusion for an Hb of 7g/dL. The other 2 patients underwent elective surgery and despite increased bleeding did not require transfusion (Fig. 1).

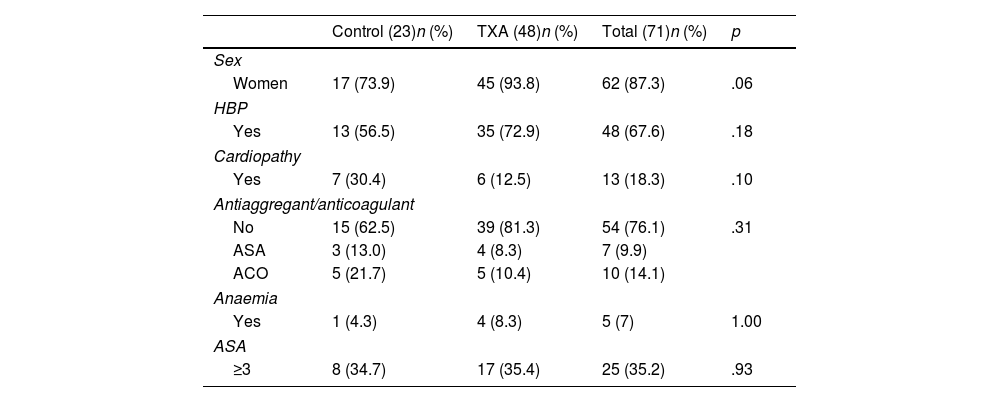

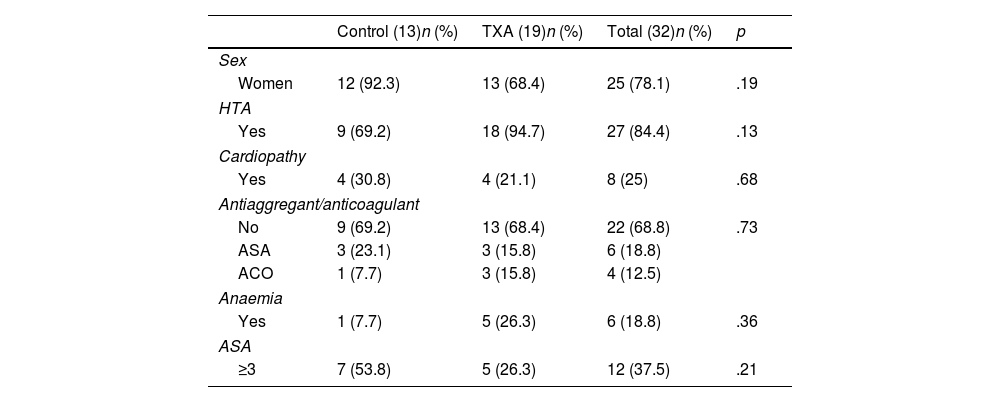

No differences were observed in ΔHb or ΔHto with respect to sex (p=.557; p=.154), hypertension (p=.183; p=.433), diagnosis of heart disease (p=.420; p=.694), anticoagulant or antiplatelet use (p=.885; p=.533), or ASA classification (p=.488; p=.466). The characteristics of both groups are comparable and are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Data of patients operated on for elective RTSA, excluding patients with coagulopathy.

| Control (23)n (%) | TXA (48)n (%) | Total (71)n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 17 (73.9) | 45 (93.8) | 62 (87.3) | .06 |

| HBP | ||||

| Yes | 13 (56.5) | 35 (72.9) | 48 (67.6) | .18 |

| Cardiopathy | ||||

| Yes | 7 (30.4) | 6 (12.5) | 13 (18.3) | .10 |

| Antiaggregant/anticoagulant | ||||

| No | 15 (62.5) | 39 (81.3) | 54 (76.1) | .31 |

| ASA | 3 (13.0) | 4 (8.3) | 7 (9.9) | |

| ACO | 5 (21.7) | 5 (10.4) | 10 (14.1) | |

| Anaemia | ||||

| Yes | 1 (4.3) | 4 (8.3) | 5 (7) | 1.00 |

| ASA | ||||

| ≥3 | 8 (34.7) | 17 (35.4) | 25 (35.2) | .93 |

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 76.8±7.1 | 74.1±6.2 | 75.5±6.53 | .99 |

Characteristics of the patients who underwent RTSA by FPH excluding patients with coagulopathy.

| Control (13)n (%) | TXA (19)n (%) | Total (32)n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 12 (92.3) | 13 (68.4) | 25 (78.1) | .19 |

| HTA | ||||

| Yes | 9 (69.2) | 18 (94.7) | 27 (84.4) | .13 |

| Cardiopathy | ||||

| Yes | 4 (30.8) | 4 (21.1) | 8 (25) | .68 |

| Antiaggregant/anticoagulant | ||||

| No | 9 (69.2) | 13 (68.4) | 22 (68.8) | .73 |

| ASA | 3 (23.1) | 3 (15.8) | 6 (18.8) | |

| ACO | 1 (7.7) | 3 (15.8) | 4 (12.5) | |

| Anaemia | ||||

| Yes | 1 (7.7) | 5 (26.3) | 6 (18.8) | .36 |

| ASA | ||||

| ≥3 | 7 (53.8) | 5 (26.3) | 12 (37.5) | .21 |

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 80.3±7.7 | 80.4±5.5 | 80.3±6.3 | .98 |

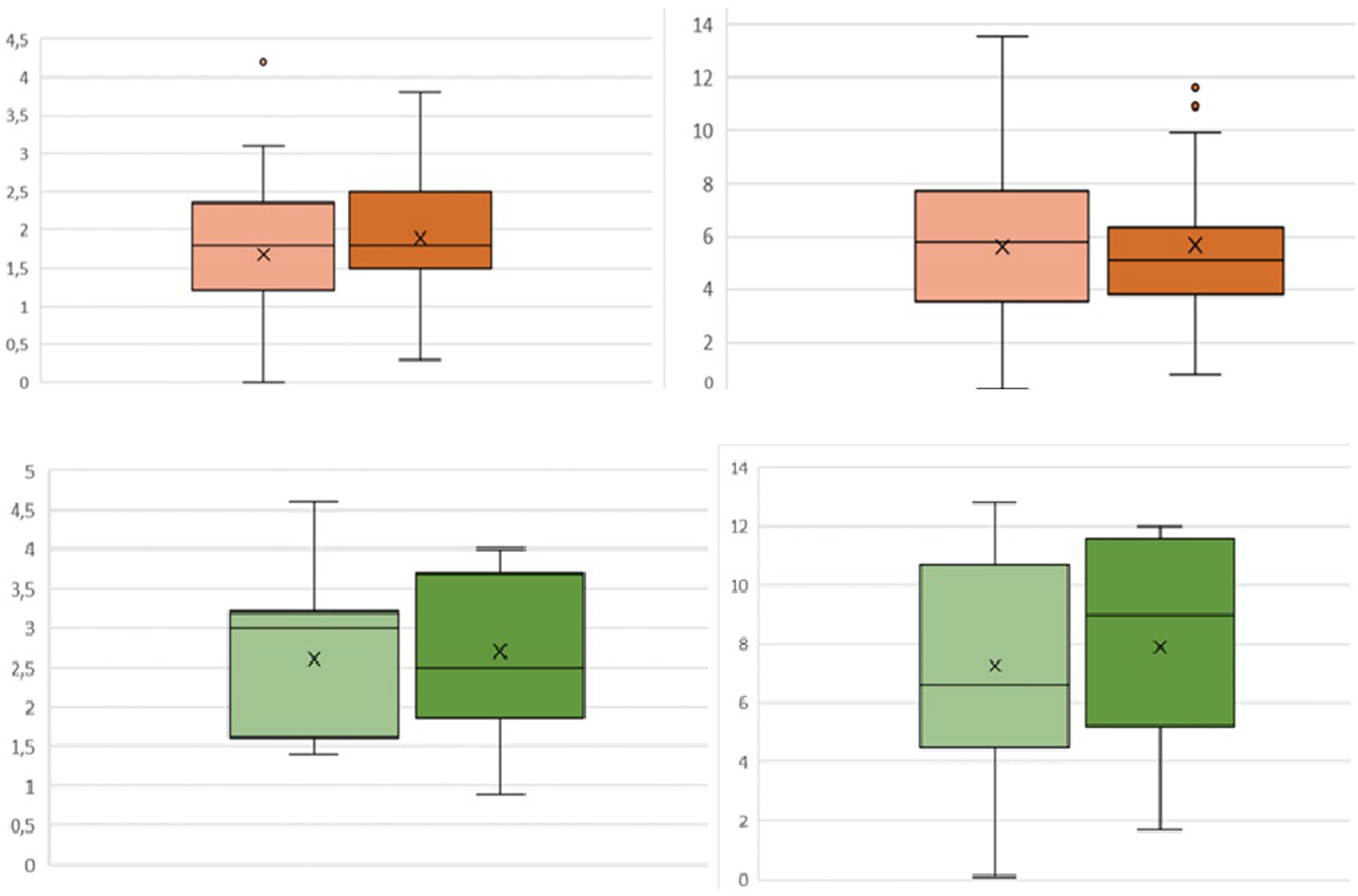

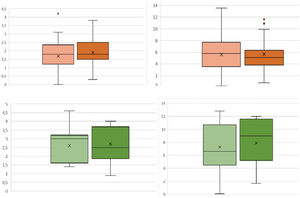

Regarding bleeding, no statistically significant differences in ΔHb or ΔHto were observed between patients who received TXA and those who did not, both in patients who underwent elective surgery and those who underwent FPH (Fig. 2). However, a 40% decrease in local bleeding was observed: in patients operated for arthropathy who received TXA the mean bleeding was 104.7±76.7mL, while the control group collected 195.5±132mL (p=.004); in the case of RTSA for fracture the control group drained 78.7±67.6mL vs. 47.1±35.5mL in the group receiving TXA (p=.01). Patients undergoing elective surgery who received TXA had a slightly shorter postoperative hospital stay, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (2.0 vs. 2.3 days, p=.34), as was the case for the fracture group (2.3 vs. 2.5 days, p=.56).

Fewer complications were observed in the arthropathy RTSA (7%) than in the fracture RTSA (15.6%, p=.04). In patients with arthropathy, 4.2% of TXA patients (2 patients) and 13% of those in the control group (3 patients) had some complication (p=.18), none related to possible adverse effects of the drug (thrombotic events, change in colour vision, etc.). In the TXA group, one episode of desaturation with hypotension and dizziness was observed, in which an embolic cause was ruled out and a subcutaneous haematoma was recorded, to which a dose of TXA (500mg) was administered orally with no subsequent problems in the wound. In the control group, one patient presented a seroma that required an additional 24h of drainage, a second patient had a periprosthetic infection at 4 months due to C. acnes that required a second surgery for debridement and implant retention, and a third patient presented with respiratory infection during admission.

In the RTSA fracture group, 5 patients presented complications (15.6%), 2 in the control group (15.3%) and 3 in the TXA group (15.7%). Of the control group, one patient required transfusion and another patient presented an episode of disorientation during admission due to a change in his medication. In the TXA group, a transfusion was also necessary, one patient suffered a small segmental PTE due to immobility at home without antithrombotic prophylaxis; the patient was studied and no signs of DVT were found on echo-Doppler. The third patient had a reactivation of a previous chronic hip infection.

All patients requiring transfusion – including the patient with coagulopathy – were women over 82 years of age who underwent FPH; the need for transfusion was related to RTSA due to fracture (0% vs. 6%, p=.02), being over 80 years of age (0% vs. 8%, p=.04) and previous use of anticoagulants (1.8% vs. 16.7%, p=.07). However, no association was found with drain use (3.3% vs. 2.3%, p=0.29) or TXA use (5% vs. 7%, p=.66).

DiscussionOur data show that topical administration of 1.5g reduces local bleeding after RTSA by 40%, without significantly influencing systemic bleeding or the need for transfusion.

As in other joints, bleeding in shoulder arthroplasty is a major concern. Although reported transfusion rates are lower than in hip or knee arthroplasty, the incidence is highly variable and increases in cases of surgery after fracture or revision arthroplasty. Revision.6,12 In hip and knee arthroplasty, there are multiple quality studies that endorse the efficacy of TXA, not only in reducing bleeding, but also other associated risks such as transfusion or infection,1,13 so that recently, with the increase in the number of shoulder arthroplasties in recent years, interest in its use in this surgery has increased. As in the hip and knee, there is no consensus on the optimal dose and the ideal route of administration. Regarding the route of administration, only Gillespie et al. published data after topical administration of TXA: they used 2g in a high-volume formulation (100mL) in patients undergoing anatomical (44 patients) and inverted (67 patients) prostheses, observing less bleeding from drainage and less bleeding in patients with anatomical prostheses, but not in those with inverted prostheses.4 Subsequent studies have used the intravenous or combined route.7–9,14–17,10,18 The use of these alternatives has shown similar results: Vara et al.10 observed less systemic bleeding, less local debit and a lower transfusion rate after administration of 2 i.v. doses. Pauzenberger et al.8 also used 2 i.v. doses and observed less haematoma and decreased pain. Other authors have also found favourable results for TXA using a single dose.7,9,15 Yoon et al. compared in a clinical trial both routes of administration and combined administration without finding any differences between them.18 Theoretical advantages of intravenous administration include its antifibrinolytic effect from the start of the procedure, while the topical route avoids potential systemic side effects and allows the surgeon to administer it independently of the anaesthetist. With the data currently available, it is not possible to determine the superiority of one route over the other, but all data point to TXA reducing bleeding associated with surgery, both topically and intravenously.

In our study, a dose of 3 ampoules of TXA was administered for a low volume formulation of 30mL and, although we observed a lower bleeding trend in both groups, these differences are not significant in systemic anaemisation (ΔHb and ΔHto). What we did observe was 65–80% higher local bleeding in patients without TXA (elective surgery: 104 vs. 195mL, p=.004; RTSA for fracture: 79 vs. 47mL, p=.01). The use of TXA reduces haematoma formation and makes it possible to consider the possibility of safely abandoning drains, simplifying postoperative care and reducing the associated cost.

Analysing post-surgical transfusion, different risk factors for its use have been proposed, including anaemia, heart disease, age, traumatic indication, type of implant (RTSA, TSA, hemiarthroplasty, revision, etc.) or even the use of cement or obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).12,19–22 These studies often include heterogeneous populations and use different implant designs. This heterogeneity partly explains the variability found in the transfusion rate, ranging from 43% to 0%.4,5 Our study includes a population that underwent surgery using the same RTSA model, corroborating that elective arthroplasty has a lower anaemisation rate than fracture RTSA, as has been observed previously.19,23 Another factor that significantly affects the transfusion rate is the protocol used in each centre. In our hospital the transfusion criteria follow the restrictive criteria set out in the recommendations of the guidelines for blood saving in patients undergoing major surgery.24 Our transfusion rate was 0% in elective surgery patients and 6% in those operated on for fractures, which is lower than other published series.

The concern to reduce transfusion needs is amply justified. Recently, Grier et al. identified 7794 patients transfused after TSA and RTSA in whom a higher rate of complications was observed, ranging from thromboembolic disease to pneumonia or surgical site infection.25 In hip and knee arthroplasty, several studies have found a correlation between the administration of TXA and a reduction in these complications.26 There are in vitro studies in favour of TXA to prevent infection by preventing the formation of bacterial biofilm through direct inhibition of lysine,27 so its local application would be a possible advantage.

While it is true that other studies have found differences in favour of TXA in reducing the need for transfusion,7,28 the only published study on shoulder arthroplasty that analyses its relationship with infection has not found significant differences between administering it or not to reduce this rate.29 In our study, being a relatively small series with a very low incidence of complications, these relationships could not be established either in the elective surgery group (0 patients transfused), or even in the fracture surgery patients (7% in the control group vs. 5% with TXA, p=.66); it was only possible to relate the risk of transfusion to patient characteristics (>80 years, female, fracture surgery, etc.). Similarly, no thromboembolic events associated with the use of TXA were observed.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the retrospective collection of data implies a significant loss of patients, although they were similar in both groups. On the other hand, the inclusion of a limited number of patients – although similar to other series – with a low incidence of complications does not allow the establishment of associations that have been seen in registry-based studies. As a strength, this study presents a homogeneous population with a single implant, so the differences observed cannot be attributed to implant design or surgical technique. In addition, this is the first study to examine the use of TXA in patients undergoing RTSA surgery for fracture, who have not been included in previous studies. Many of these patients have a history of thromboembolic disease or heart disease, and it is precisely these patients with increased bleeding and risk of transfusion who may benefit most from TXA. Larger studies are needed to determine the specific impact on transfusion needs in this more fragile population.

ConclusionThe use of locally administered low volume 1.5g TXA in a low volume formulation effectively reduces bleeding in patients undergoing RTSA surgery; in addition, in patients undergoing RTSA surgery for arthropathy, the average hospital stay was also reduced.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

FundingNone of the authors received any funding for this research study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Ethics committee approvalResearch approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital (PI-4267).