There is an increase in degenerative arthropathies because of the increase in the longevity of world's population, making primary knee arthroplasties a procedure to recover quality of life without pain. There are factors associated with the length of hospital stay after this procedure.

ObjectiveTo determine the risk factors influencing the hospital stay during the postoperative period of patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty with an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol (ERAS).

MethodsA retrospective study is carried out on patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty at an University Hospital in the period 2017–2020 using the ERAS protocol, during which 957 surgeries were performed.

ResultsAverage age of 71.7±8.2years, 62.4% were women and the 77.3% were classified as ASA II. The significantly associated factors to an increased length of stay are: age (p=.001), ASA scale (p=.04), day of surgery (p<.001), blood transfusion (p<.001), postoperative haemoglobin level at 48–72h (p<.001), the time of first postoperative mobilisation to ambulate and climb stairs (p<.001), the need for analgesic rescues (p=.003), and the presence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (p=.008).

ConclusionsThere are statistically significant and clinically relevant factors associated with hospital stay. Determining these factors constitutes an advantage in hospital management, in the development of strategies to improve and optimise the quality of care and available health resources.

Existe un incremento de las artropatías degenerativas como consecuencia del aumento en la longevidad de la población mundial, haciendo de las artroplastias primarias de rodilla un procedimiento para recuperar calidad de vida sin dolor. Existen factores asociados al tiempo de estancia hospitalaria después de este procedimiento.

ObjetivoDeterminar los factores que influyen en la estancia hospitalaria durante el posoperatorio de pacientes sometidos a artroplastia primaria total de rodilla con un protocolo de recuperación mejorada después de la cirugía (ERAS).

MétodosSe realiza un estudio retrospectivo de pacientes sometidos a artroplastia primaria total de rodilla en un hospital universitario en el periodo 2017-2020 mediante el protocolo ERAS, durante el cual se realizaron 957 cirugías.

ResultadosLa edad media fue de 71,7±8,2 años, el 62,4% fueron mujeres y mayoritariamente ASA II (77,3%).

Los factores asociados significativamente con el aumento de estancia hospitalaria son la edad (p=0,001), el ASA (p=0,04), el día de la cirugía (p<0,001), la transfusión sanguínea (p<0,001), el nivel de hemoglobina posoperatoria y a las 48-72horas (p<0,001), el momento de la primera movilización posoperatoria para deambular y subir escaleras (p<0,001), la necesidad de rescates analgésicos (p=0,003) y la presencia de náuseas y vómitos posoperatorios (p=0,008).

ConclusionesExisten múltiples factores estadísticamente significativos y clínicamente relevantes asociados a la estancia hospitalaria. Determinar estos factores constituye una ventaja en la gestión hospitalaria, en el desarrollo de estrategias de mejora y optimización de la calidad asistencial y en la distribución de los recursos sanitarios.

An increase in the population affected by degenerative knee diseases in advanced phases has been currently observed, particularly in the elderly.1 In the autonomous community of the Basque Country the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis is 12.2%.2 In Catalonia is has been estimated that 28% of the population older than 60 suffer from osteoarthritis.3

This type of osteoarthritis leads to pain and impairment in quality of life. Total primary knee arthroplasty (TKA) therefore constitutes an effective alternative treatment for improvement in pain and quality of life in the final stages of the disease, when conservative treatment is no longer effective. The number of Americans who have joint replacements is high, amounting to 7 million citizens,4 of whom 4.7 million have knee replacements mainly due to advanced osteoarthritis. Given such a volume of procedures improving the pre-peri and post-intervention care protocols could reduce costs of approximately 2,054,123 euros per year in a high-volume hospital.5

Improved recovery protocols in orthopaedic surgery (enhanced recovery after surgery or ERAS) are the implementation of multidisciplinary clinical action pathways focused on the enhanced recovery of the patient during the hospitalisation period and afterwards.6–9 These protocols offer improvements for patients, institutions and healthcare systems, although there are differences in application between the centres and services.10

The use of these clinical protocols enhances care quality and optimises the use of resources.11 This leads to reduced hospital stays by 2–3 days12 and a high level of patient satisfaction.

There is some evidence that patients of centres where ERAS protocols were applied had lower rate of complications during the postoperative period (10% vs 13%) and achieved higher rates of optimum functional outcomes. There is also a lower hospital stay in centres with ERAS protocols compared with those that do not use them.9,13–15 It is therefore important to manage resources and efforts in aligning the care procedures and protocols towards effective and efficient objectives, in highly prevalent operations such as knee arthroplasties.16,17

The purpose of this study was to determine which factors impact hospital stay during the postoperative period of patients who have undergone a total primary knee arthroplasty with the ERAS protocol.

Material and methodsStudy designThis was a retrospective analysis study in which hospital data were reviewed from the medical history of patients who underwent TKA using the ERAS protocol in a university hospital during the 2017–2020 periods and thus determining the variables that may have impacted the length of hospital stay.

The study was approved by the Research and Medication Ethics Committee (CEIm) of our centre, with the code CEIC-2619.

Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on the Protection of personal data and guarantee of digital rights was applied to data collection, and a pseudonymisation procedure was carried out by a third person outside the study.

The inclusion criteria were: patients over 18 years of age undergoing primary knee arthroplasty and whose diagnosis was degenerative knee osteoarthritis, post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis or knee osteoarthritis caused by inflammatory disease.

The exclusion criteria were: patients with bilateral knee prostheses in the same episode; patients in whom unicompartmental knee arthroplasty was performed; patients undergoing revisions of previous knee arthroplasty, and those whose diagnosis was not joint osteoarthritis.

Hospital ERAS protocolThe intervention analysed in this study was the ERAS protocol applied in our centre. This was formulated by multidisciplinary work groups, following the recommendations of scientific evidence, the opinions and ideas of professionals, patient preferences and the idiosyncrasies of the centre. The continuous and critical review of previous care processes has meant that many of them had been modified, eliminated or replaced by others. The most important changes with respect to the previous care protocol that defined the current ERAS clinical pathway of our centre are listed in Table 1.

ERAS protocol applied in our centre.

| Preoperative |

| • Pre-intervention education sessions (carried out by a nurse and a physiotherapist, where the process is explained, the exercises to be performed are practiced and fears and/or anxieties are resolved by interacting with a previously operated patient).• Patient enhancement and preparation programme (elimination of risk factors, such as smoking or alcohol habits).• Blood saving programme: treatment of preoperative anaemia according to analysis (oral iron, i.v. iron or erythropoietin).• Solids intake up to 6h prior to the intervention.• Liquids intake up to 3h prior to the intervention.• MRSA screening programme and decolonisation. |

| Perioperative |

| • Pre-emptive analgesia, Celecoxib 200mg p.o. 2h before surgery.• Tranexamic acid 10mg/kg i.v. 15–30min before the surgical incision.If there is no contraindication• Combination of spinal anaesthesia with local aesthetic infiltration (LAI) technique with ropivacaine, adrenaline and ketorolacombinación.• Elimination of the use of drains.• Elimination of the urinary catheter.• Elimination of the ischaemia cuff during all surgery.• Tranexamic acid 2g intra-articular at the end of the intervention. |

| Postoperative |

| • Postoperative intravenous oral analgesia (paracetamol 1g/6h p.o.+celecoxib 200mg/12h p.o.+oxycodone naloxone 10mg/12h p.o. rescue).• Liquid intake after 3h.• Solids intake after 6h.• Beginning of early rehabilitation: mobilisation, sitting and walking less than 24h post-intervention.• Reinforcement of analgesic control with postoperative adductor canal block if pain control is poor.• Postoperative intravenous iron therapy.• Restrictive transfusional policy.• Improved reconciliation with home medication.• Modification of the content and timing of the different rehabilitation interventions (more active techniques that promote the patient's autonomy and independence, not the use of passive movement systems).• Airtight dressings and full shower authorisation after two days.• Registration due to compliance with criteria and not due to a specific stay. |

The variables were obtained from a review of the medical history of each patient through the computer system database of all patients with an active medical history in the regional public health system, and also from the hospital data collection record of the ERAS protocol agreed upon and used in our centre.

The variables for the study were: demographic values such as age, sex, day of surgery and surgery shift; clinical variables such as pre-surgical haemoglobin (Hb), post-surgical Hb at 24h, post-surgical Hb at 48–72hours, American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) scale, blood transfusion, number of units transfused; functional variables such as day of sitting, walking and stairs and some postoperative follow-up variables such as rescue analgesic, episodes of nausea and vomiting, readmission in the first 30 days; All were analysed according to their relationship and impact on length of hospital stay.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed with the updated version of PSPP-1.4-1.2 software. Variables are described as mean ((±standard deviation) or as a percentage.

The individual relationship of the stay with continuous variables such as age; pre- and post-surgical Hb; number of blood transfusion units; number of analgesic rescues; and number of postoperative nausea and vomiting was analysed using the Spearman test. Discreet variables, such as sex; laterality; time of surgery; blood transfusion, and readmission within the first 30 days were analysed with the Mann–Whitney test. The Kruskall–Wallis test was used to observe the influence of the ASA scale on the day of surgery, and the day of sitting, walking and climbing stairs.

Logistic regression and multivariate analysis were subsequently made to analyse the group behaviour of the variables with regard to the length of hospital stay.

ResultsNine hundred and fifty-seven patients were included, 360 of whom were men (37.6%) and 597 women (62.4%), with a mean age of 71.7years (range: 38–90 years). Right TKA was performed in 495 (51.7%) and left in 462 (48.3%).

Seventy-seven point three per cent (n=740) were ASA II, 16.9% (n=162) ASA III, 5.4% (n=52) ASA I and .3% (n=3) ASA IV.

They were operated on four different days of the working week. Thus, 264 knee arthroplasties on Monday, 155 on Wednesday, 404 on Thursday and 134 on Friday, representing 27.6%, 16.2%, 42.2% and 14%, respectively.

Regarding the morning or afternoon operating room shifts, 480 (50.2%) surgeries were recorded in the morning shift and 477 (49.8%) in the afternoon shift.

The overall average hospital stay was 4.20±1.42 days. Demographic data are reported in Table 2.

Demographic data.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 957 (71.7±8.2) | |

| Sex | ||

| Man | 360 | 37.6% |

| Woman | 597 | 62.4% |

| ASA | ||

| I | 52 | 5.4% |

| II | 740 | 77.3% |

| III | 162 | 16.9% |

| IV | 3 | .3% |

| Laterality | ||

| Right | 495 | 51.7% |

| Left | 462 | 48.3% |

| Day of the week | ||

| Monday | 264 | 27.6% |

| Wednesday | 155 | 16.2% |

| Thursday | 404 | 42.2% |

| Friday | 134 | 14.0% |

| Shift | ||

| Morning | 480 | 50.2% |

| Afternoon | 477 | 49.8% |

The values are shown as numbers and percentages.

The mean preoperative Hb was 14.12±1.29mg/dl (95% CI: 14.04–14.20); the mean Hb at 24h was 11.67±1.38mg/dl (95% CI: 11.58–11.75), and the mean Hb at 48–72h was 10.82±1.35mg/dl (CI 95%: 10.73–10.90). 45 patients (4.7%) were transfused. The total number of blood concentrates transfused is 80, with an average of 1.78±.5 concentrates received per transfused patient.

Regarding the time of the first mobilisation and the first postoperative sitting and walking, they were .39±.51 (95% CI: 0.35–0.42) day and .43±.54 (95% CI: 0.39–0.46) day, respectively, considering day 0 as the day of surgery. The mean for starting to climb stairs was 2.28±1.29 (95% CI: 2.20–2.36) days after surgery.

Patients required an average of 1.73±1.56 (95% CI: 1.63–1.82) analgesic rescues and suffered .44±.75 (95% CI: 0. 40–0.49) episodes of postoperative nausea and vomiting per patient.

There were 29 90-day readmissions, of which 17 (58.6%) were in the first 30 days. The causes of readmission at 30 days were: 2 joint infections; 1 quadriceps rupture; 1 suspected deep vein thrombosis; 7 wound problems, and 6 wound-related problems.

The results of the clinical and analytical variables are summarised in Table 3.

Clinical-analytical data.

| 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | Low | High | |

| Stay | 957 | 4.20±1.42 | 4.11 | 4.29 |

| Preoperative Hb | 956 | 14.12±1.29 | 14.04 | 14.20 |

| Hb 24h | 957 | 11.67±1.38 | 11.58 | 11.75 |

| Hb 48–72h | 957 | 10.82±1.35 | 1.73 | 10.90 |

| Transfusion | ||||

| Yes | 45 | 4.7% | ||

| No | 912 | 95.3% | ||

| Sitting | 957 | .38±.51 | .35 | .41 |

| Walking | 957 | .42±.54 | .39 | .46 |

| Stairs | 953 | 2.28±1.29 | 2.20 | 2.36 |

| Rescues | 955 | 1.72±1.56 | 1.62 | 1.82 |

| Vomiting | 956 | .44±.74 | .39 | .49 |

CI: confidence interval; Hb: haemoglobin.

The values are shown as numbers, percentages, mean±standard deviation and CI according to the type of variable.

Significant results were obtained from the individual association analysis with the length of hospital stay in the variables age; day of surgery; ASA scale; preoperative Hb; Hb 24h; Hb 48–72h; blood transfusion; packed red blood cells; analgesic rescues; postoperative nausea and vomiting; sitting; walking and climbing stairs (Table 4).

Analysis of individual association of factors in relation to the length of hospital stay.

| Variable | Test | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Sp | .001 |

| Sex | MW | .873 |

| Laterality | MW | .963 |

| Day of the week | KW | <.001 |

| Shift | MW | .170 |

| ASA | KW | .04 |

| Preoperative | Sp | .054 |

| Hb at 24h | Sp | <.001 |

| Hb at 48–72h | Sp | <.001 |

| Transfusion | MW | <.001 |

| Red blood cell concentrate | Sp | <.001 |

| Rescue analgesics | Sp | .003 |

| Postoperative vomiting and nausea | Sp | .008 |

| Sitting | KW | .002 |

| Walking | KW | <.001 |

| Stairs | KW | <.001 |

| Readmission | MW | .567 |

ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiology; Hb: haemoglobin; KW: Kruskal–Wallis test; MW: Mann–Whitney test; Sp: Spearman test.

The values of p<.05 represent statistical significance between the variables and length of hospital stay.

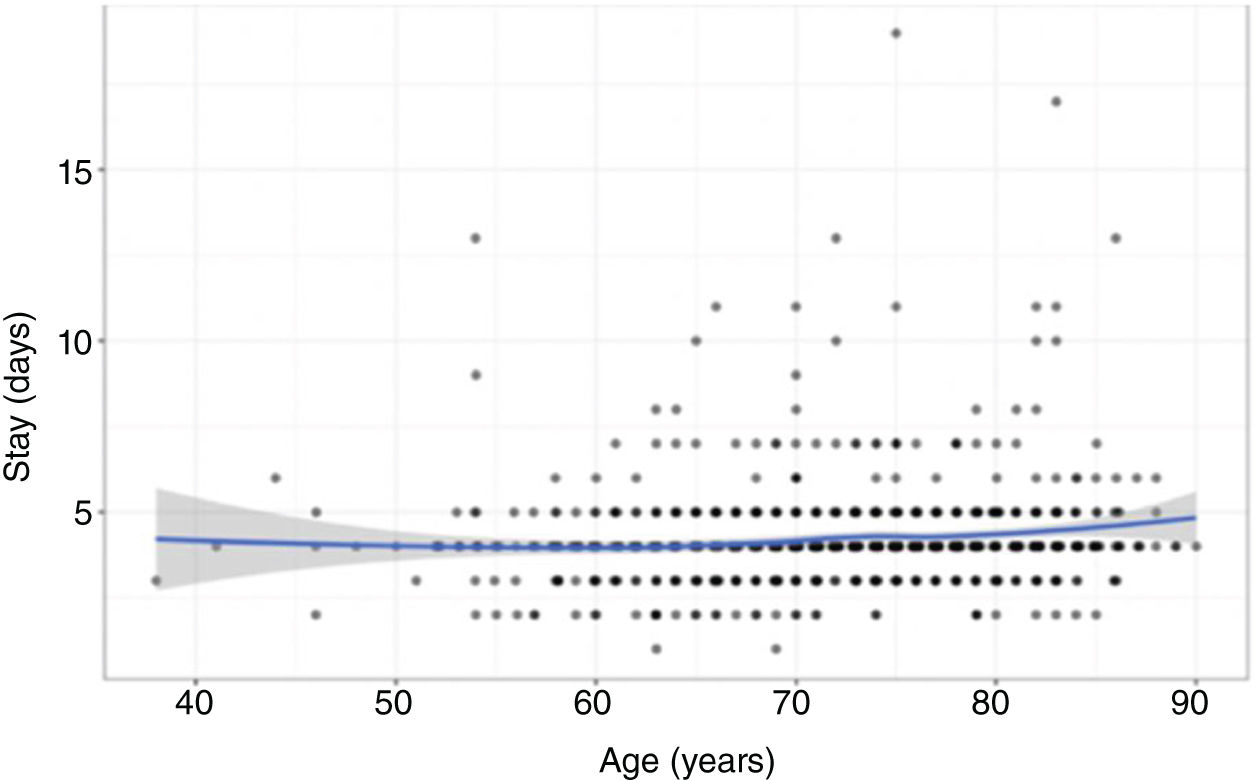

Age, with p=.001 (OR=.02; 95% CI: .01–.03), indicates that increasing age increases the probability of prolonging hospital stay (Fig. 1).

The ASA classification (p=.04) (OR ASA II–ASA I: .22, CI 95%: −.16 to .59; −2.71 to 1.07), where ASA is considered I as value 1, which on average has a mean hospital stay of 3.73days, indicating that ASAIII are 60% more likely to prolong the stay more than 3days (Fig. 2).

Regarding the day of intervention, patients operated on Thursday obtained p≤.001 (OR Thursday–Monday: .26, 95% CI: −.01 to .53), showing that those operated on Thursday will have an 80% probability of prolonging their hospital stay compared to those who underwent surgery on Monday.

Regarding the postoperative analysis, Hb at 24h (p=.01, OR: .13, 95% CI: .02–.24) and Hb at 48–72h (p<.001, OR: −.17, 95% CI: −.27 to −.07), more significantly indicates that mean Hb values in the normal range at 48–72h reduce the risk of prolonging hospital stay (Fig. 3).

The first mobilisation of walking and climbing stairs for the first time (p<.001) is related to fewer days of hospital stay.

Analgesic rescues (p=.003) and postoperative nausea and vomiting (p=.008) are directly correlated with the length of hospital stay.

The average stay was 5.11±1.64 days vs. 4.16±1.39 days between those who received a transfusion and those who did not, respectively (p<.001) (Fig. 4).

Regarding the multivariate logistic linear regression analysis to observe the group behaviour of the variables, the association results were maintained except for the sitting variable, which initially presented significance independently, but when the correlation and multivariate statistical adjustment were made, its value and clinical relevance was lost.

DiscussionDetermining the factors that significantly impact the length of hospital stay is important so as to provide adequate care and improve outcomes, together with optimal distribution of available health resources.

The main strengths of this study were the high number of patients analysed who adhered to the standardised protocol, and that, in addition to an individual association study, a multivariate regression analysis was performed.

The main limitation of our study is that it was retrospective. Moreover, the coding of minor complications was difficult due to the non-uniformity of clinical notes, leading to the selection of a more robust variable, such as readmissions.

Numerous articles show the improvement in outcomes obtained in hospital institutions where an ERAS protocol was implemented,6,7,12,14,18 although differences occur in the protocols of each hospital centre. An improvement in pre- and post-implementation indicators was also present in our centre.

Our study clearly demonstrates the relationship between the length of hospital stay and various factors such as age; day of intervention; ASA scale; Hb levels at 24 and 48–72h postoperatively; the first mobilisation; analgesic rescues, and postoperative nausea and vomiting. This was also indicated by Husted et al.19 who found that highly determining factors were associated with a hospital stay of more than 3 days. It therefore appears that hospital stay is not determined by a single factor, but by a set of multiple variables.

The increase in age is directly proportional to the increase in hospital stay (p=.001).19–21 There was an 80% greater probability of a longer than 4-day hospital stay for those who underwent surgery on Thursday. This was related to the lack of physiotherapy at weekends in our centre, proving that not only clinical factors, but also logistics, can impact hospital stay. Some authors propose that performing physiotherapy at weekends has been proven to reduce costs and days of hospitalisation.22–25 The ASA classification significantly influences hospital stay,26 as described in the work by Li et al.,27 where they found that laboratory factors and the ASA level could increase the length of stay.28 In our study, subjects with ASA III had a higher risk of presenting postoperative complications and prolonged hospital stay.

Low Hb levels at 24 and 48–72h after surgery also increase the probability of prolonging hospital stay (p<.001). However, in the work presented by Smith et al.21 no relationship was observed between these two factors; On the contrary, according to other authors, correction of preoperative Hb levels and control of postoperative bleeding could optimise results and hospital stay.24

Our study showed a low percentage of transfusions, which have a tendency to lengthen hospital stay as a consequence of the increase in post-transfusion comorbidity.

Another important point is early mobilisation, since people who walk and climb stairs later in the postoperative period have a high probability (p<.001) of extending their hospital stay, as described by Yakkanti et al.,22 who found differences between mobility on the day of surgery vs. the first day after surgery.25–27 Regarding the need for rescue analgesics, for postoperative nausea and vomiting, a direct and significant relationship was observed for increased hospital stay in those people who have more episodes. In this regard, Lunn et al.29,30 report that there is less need for analgesia and antiemetics if preoperative medication is administered.

ConclusionsThe results obtained in this descriptive study indicate that multiple factors, such as age; day of surgery; ASA level; blood transfusion; postoperative Hb; early mobilisation with physiotherapy; analgesic rescues; and postoperative nausea and vomiting, are statistically significantly related to the length of hospital stay after performing TKA with the ERAS approach at our institution. This proves that hospital stay does not depend on a single factor, but on a combination of both clinical and logistical factors, which must be analysed to improve clinical and procedural pathways in order to optimise available resources and the quality of care provided to the population.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or not-for-profit entities.

Conflict of interestsThere was no conflict of interests in the preparation of this study.