Peroneal tendon pathologies are an important cause of pain in the lateral aspect of the ankle. It has been proposed in the literature that low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly occupies more space in the retromalleolar groove and could cause laxity of the superior retinaculum which would promote tendon dislocation, tenosynovitis or ruptures. The objective of the study is to characterise the population with low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly and determine the association between the low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly found on magnetic resonance imaging and clinical peroneal tendon dislocation.

MethodsA case–control study was developed with a sample of 103 patients. The cases were patients with low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly and peroneal dislocation and the controls were patients with normal implantation of the peroneus brevis muscle and peroneal tendon dislocation.

ResultsThe prevalence of clinical peroneal dislocation in patients with low implantation of the peroneal brevis muscle belly was 7.64%, and the prevalence of clinical peroneal dislocation in patients with normal implantation of the peroneus brevis muscle belly was 8.88%. The OR was 0.85 (CI 0.09–7.44, p=0.88).

DiscussionOur findings indicate that there is no statistically significant relationship between low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly and clinical dislocation of the peroneal tendons.

Las patologías de los tendones peroneos son una causa importante de dolor en la región lateral del tobillo. Se ha propuesto en la literatura que la implantación baja del vientre muscular del peroneo corto ocupa más espacio en el surco retromaleolar y podría causar laxitud del retináculo superior asociándose a luxación de los tendones, tenosinovitis y/o roturas. El objetivo del estudio es caracterizar la población con implantación baja del vientre muscular del peroneo corto y estudiar la asociación entre la implantación baja del vientre muscular del peroneo corto visualizado en la resonancia magnética y la luxación de los tendones peroneos.

MétodosSe desarrolló un estudio de casos y controles con una muestra de 103 pacientes. Los casos fueron pacientes con luxación de los tendones peroneos e implantación baja del vientre muscular del peroneo corto y los controles pacientes con luxación de los tendones peroneos e implantación normal del vientre muscular del peroneo corto.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de luxación clínica de los tendones peroneos en pacientes con implantación baja del vientre muscular del peroneo corto fue de 7,64%, y la prevalencia de luxación clínica de los tendones peroneos en pacientes con implantación normal del vientre muscular del peroneo corto fue de 8,88%. El OR fue de 0,85 (IC 0,09-7,44, p = 0,88).

DiscusiónNuestros hallazgos sugieren que no existe una relación estadísticamente significativa entre la implantación baja del vientre muscular del peroneo corto y la luxación clínica de los tendones peroneos.

Peroneal tendon pathologies are a major cause of pain in the lateral region of the ankle. Three categories of peroneal pathologies can be distinguished, namely tenosynovitis, tears, and tendon subluxation or dislocation, which are often diagnosed late, as they are difficult to discriminate from lateral ligament injuries of the ankle. The average delay in diagnosis reported in the literature is 0–80 weeks.1

The peroneus brevis originates from the distal two-thirds of the fibula and the intermuscular septum and transitions to tendon 2–3cm proximal to the tip of the fibula. The superior retinaculum extends up to 1.5cm from the tip of the fibula.2 It has been proposed in the literature that the short muscle belly of the peroneus brevis, i.e. between or inferior to the superior retinaculum, causes the peroneus brevis to occupy more space in the retromalleolar sulcus and may cause laxity of the superior retinaculum and be associated with tendon dislocation, tenosynovitis, and/or tears.3–7

A number of studies have indicated that a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly is a common anatomical variant. Dombek et al. found a 33% prevalence of low implantation of the peroneus brevis.3 Using the same definition, Mirmiran et al. also found a high prevalence (62%).4 An MRI radiological study in asymptomatic patients found that the musculotendinous junction of the peroneus brevis was frequently below the tip of the fibula (25/65 ankles) and, based on their findings, proposes that a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly is defined when the muscle belly is 15mm or less from the tip of the fibula, which is a common finding in asymptomatic patients.8

The sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to detect peroneal tendon pathology is variable. In the case of tears, sensitivity rates of 85% and specificity rates of 62% have been reported.9 The study by Mirmiran et al. reported 10% sensitivity and 100% specificity for subluxations.3 It is important to consider that MRI is a static tool that must be complemented by clinical examination to confirm the presence of tendon dislocation, which is a dynamic finding.

There is evidence that confirms the relationship between a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly and tears of these tendons.4–7 On the other hand, there are also studies that report a high prevalence rate of a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly associated with few tears10 or in asymptomatic patients.8 There is even a study that found that distal extension of the peroneus brevis muscle belly was correlated with a lower prevalence of tears with respect to a high muscle belly.10 These papers did not probe the association between peroneal tendon dislocation and a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly. So much contradictory information calls this relationship into question; there are studies that commonly observe this anatomical variant in asymptomatic patients.11 We hypothesise that there is no relationship between the presence of a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly and peroneal tendon dislocation. The purpose of this study, then, is to assess whether there is a correlation between a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly and peroneal tendon dislocation.

Materials and methodsThe present research work was approved by the ethics committee of our university. The study population consisted of patients who visited the foot and ankle clinic with one of the authors. Our study variable was clinical peroneal tendon dislocation.

A case–control study was undertaken with a sample of 103 subjects with peroneal tendon dislocation and a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly and controls with peroneal tendon dislocation and normal attachment of the peroneus brevis muscle belly. The inclusion criteria comprised individuals of legal age with any foot and ankle pathology, including peroneal tendon pathology, who had digital MRI scans that enabled standardised measurements to be made using a visualisation programme. In all patients, regardless of the reason for consultation, the presence of peroneal tendon dislocation was assessed during the physical examination. Subjects with previous surgery on the peroneal tendons or conditions that hinder visualisation and measurement on the MRI and patients in whom clinical provocation manoeuvres could not be performed to determine the presence of peroneal tendon dislocations were excluded.

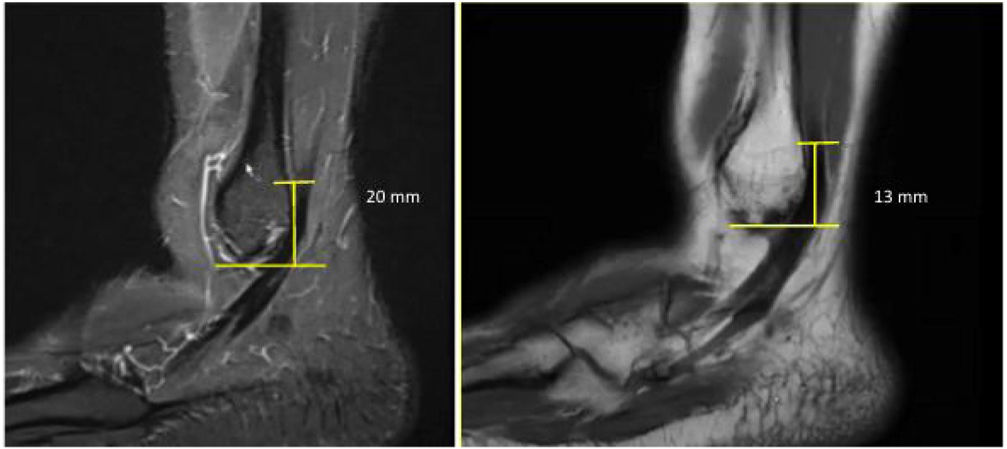

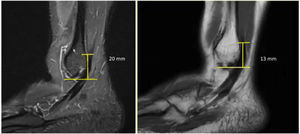

Demographic variables such as age, sex, laterality, and the patients’ main pathology, as well as other radiological variables on MRI, such as the distance from the tip of the fibula to the origin of the peroneus brevis tendon were evaluated to determine the presence of a low attachment of the peroneal muscle belly (Fig. 1). A low implantation of the peroneus brevis was defined as the muscle belly being less than 15mm from the tip of the fibula.7 On physical examination, the presence of peroneal dislocation was assessed by provocative manoeuvres, such as dorsiflexion and eversion of the ankle.

A descriptive analysis of quantitative variables was carried out using measures of central tendency and qualitative variables were evaluated using frequency tables. For the analysis of qualitative variables, a comparison of proportions was performed using the chi-square test. To determine the causal association between low implantation and tendon dislocation, the Odds Ratio (OR) was determined with a 95% confidence interval and a p value of significance of .05.

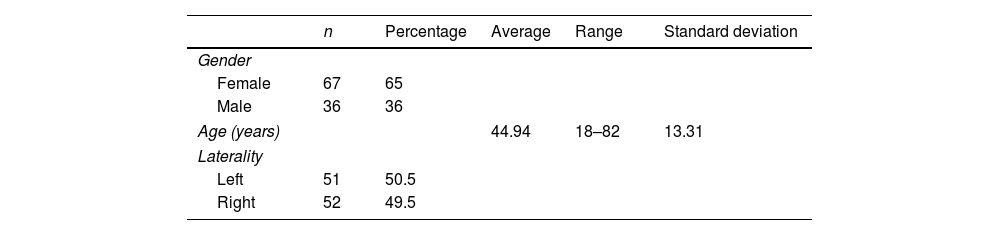

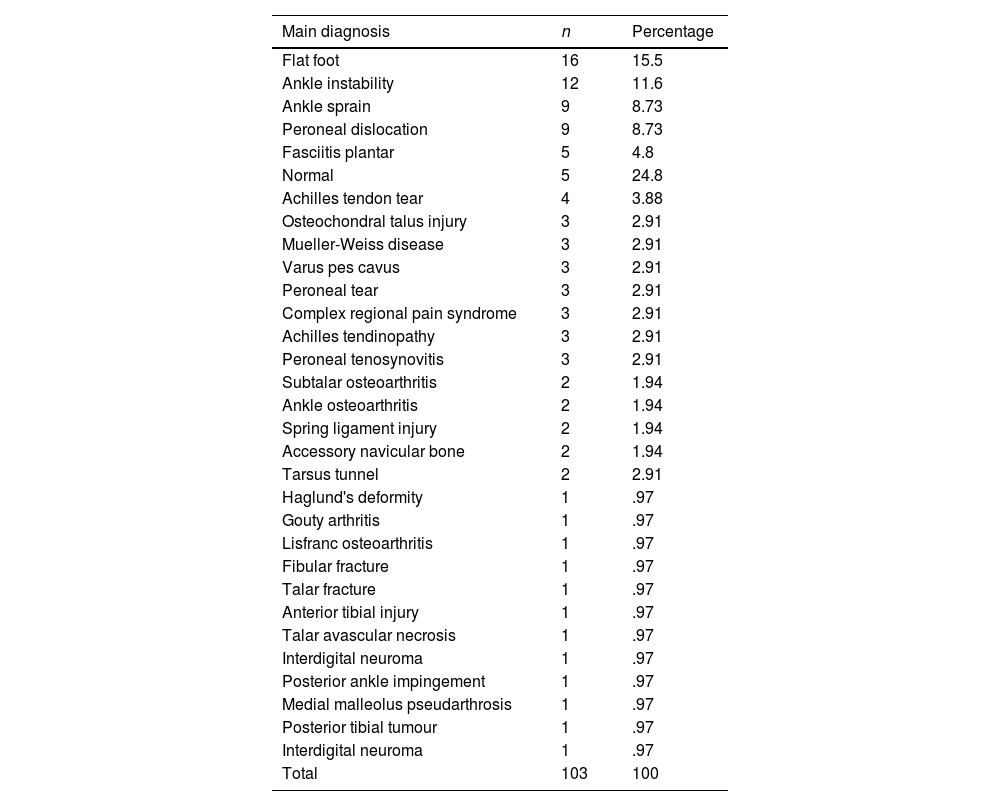

ResultsOf the 103 participants, 65% (n=67) were female, while 35% (n=36) were male. The average age was 44.96 years (18–82 years). Of the sample, 49.5% (n=51) were left ankles and 50.5% (n=52) were right ankles (Table 1). The most common pathology in the sample was flat feet (15.5%; n=16). A total of 14.5% (n=15) of the cases had peroneal tendon pathology, of which 8.7% (n=9) of the total had tendon dislocation; 2.9% (n=3) had tenosynovitis, and 2.9% (n=3) had tears (Table 2).

Main diagnoses.

| Main diagnosis | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Flat foot | 16 | 15.5 |

| Ankle instability | 12 | 11.6 |

| Ankle sprain | 9 | 8.73 |

| Peroneal dislocation | 9 | 8.73 |

| Fasciitis plantar | 5 | 4.8 |

| Normal | 5 | 24.8 |

| Achilles tendon tear | 4 | 3.88 |

| Osteochondral talus injury | 3 | 2.91 |

| Mueller-Weiss disease | 3 | 2.91 |

| Varus pes cavus | 3 | 2.91 |

| Peroneal tear | 3 | 2.91 |

| Complex regional pain syndrome | 3 | 2.91 |

| Achilles tendinopathy | 3 | 2.91 |

| Peroneal tenosynovitis | 3 | 2.91 |

| Subtalar osteoarthritis | 2 | 1.94 |

| Ankle osteoarthritis | 2 | 1.94 |

| Spring ligament injury | 2 | 1.94 |

| Accessory navicular bone | 2 | 1.94 |

| Tarsus tunnel | 2 | 2.91 |

| Haglund's deformity | 1 | .97 |

| Gouty arthritis | 1 | .97 |

| Lisfranc osteoarthritis | 1 | .97 |

| Fibular fracture | 1 | .97 |

| Talar fracture | 1 | .97 |

| Anterior tibial injury | 1 | .97 |

| Talar avascular necrosis | 1 | .97 |

| Interdigital neuroma | 1 | .97 |

| Posterior ankle impingement | 1 | .97 |

| Medial malleolus pseudarthrosis | 1 | .97 |

| Posterior tibial tumour | 1 | .97 |

| Interdigital neuroma | 1 | .97 |

| Total | 103 | 100 |

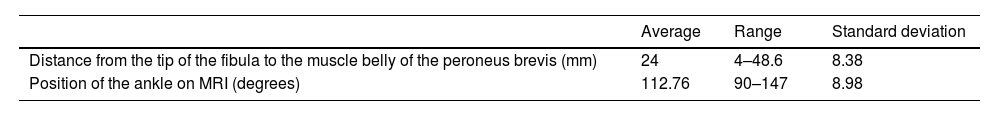

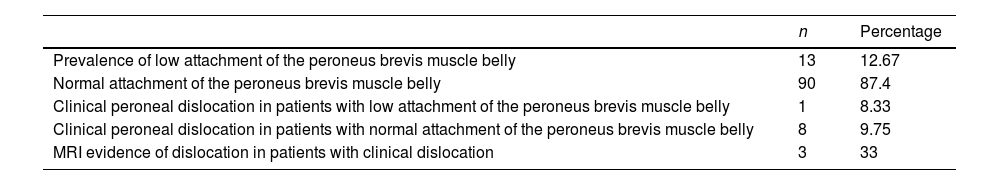

The mean distance from the tip of the fibula to the origin of the peroneus brevis tendon was 24mm (4–48.6mm). The mean MRI position of the foot axis relative to the tibial axis was 112.7° (90–147°) (Table 3). There was a 12.6% (n=13) prevalence rate of a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly (<15mm). The prevalence of normal implantation of the muscle belly of the peroneus brevis (>15mm) was 87.4% (Table 4). There were no cases of short peroneal muscle bellies below the tip of the fibula.

Radiological measurements and clinical correlation with peroneal dislocation.

| n | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of low attachment of the peroneus brevis muscle belly | 13 | 12.67 |

| Normal attachment of the peroneus brevis muscle belly | 90 | 87.4 |

| Clinical peroneal dislocation in patients with low attachment of the peroneus brevis muscle belly | 1 | 8.33 |

| Clinical peroneal dislocation in patients with normal attachment of the peroneus brevis muscle belly | 8 | 9.75 |

| MRI evidence of dislocation in patients with clinical dislocation | 3 | 33 |

| Risk factor | Cases (N=13)n (%) | Controls (N=90) | OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low attachment of the peroneus brevis muscle belly | 1 (7.69) | 8 (8.88) | 0.85 (0.09–7.44) | .88 |

MR: magnetic resonance.

The prevalence of clinical peroneal tendon dislocation in individuals with a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly was 7.69%, while the prevalence of clinical peroneal tendon dislocation in participants with a normal implantation of the peroneus brevis muscle belly was 8.88% (Table 4). The calculated OR was 0.85 with a confidence interval (CI) of 0.09–7.44 and a p-value of .88.

DiscussionThere are three primary pathologies of the peroneal tendons; i.e. tenosynovitis, tears, and dislocation. Tenosynovitis and tears are more common and there is clear controversy in the literature as to whether there is a relationship between a low peroneus brevis muscle attachment and these pathologies. Nevertheless, some studies suggest that it is a risk factor,4–6 while other studies do not substantiate this claim10; however, the relationship between low peroneus brevis muscle attachment and tendon dislocations or subluxations has been largely unexplored.

In our study, we found that the prevalence of clinical peroneal tendon dislocation in patients with a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly was similar to that in individuals in whom attachment of the peroneus brevis muscle belly was normal (8.88% vs. 7.69%). We calculated an OR of 0.85 (CI 0.09–7.44), which was not statistically significant (p=.88) and a 1.19% (CI-24, 79–11.13) difference in proportion, which also proved not to be statistically significant (p=.88). On the basis of these findings, it is impossible to affirm that low peroneus brevis implantation is related to a higher frequency of peroneal tendon dislocation.

There are few studies that have probed this association between low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly and peroneal tendon dislocation. Similar to the work by Mirmiran et al.,3 we found no statistically significant association between a low attachment of the peroneus brevis muscle belly and clinical dislocation of the peroneal tendons.

One of the limitations of our study is the low prevalence rate of peroneal tendon dislocation in our sample. On the other hand, this is a radiological study using magnetic resonance imaging in which the position of the foot can have a bearing on the height of the muscle belly of the peroneus brevis.11,12 The mean position of the foot relative to the tibial axis in our study was 112.76° (90–147°, SD 8.98), which may underestimate the prevalence of low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly. It is worth pointing out that we did not observe any participants in whom the peroneus brevis muscle belly was present below the tip of the fibula, as has been reported in other studies, a factor that could yield different results.

ConclusionsWe believe that further studies are required to investigate the relationship between low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly and peroneal tendon dislocation. The findings of our study suggest that a low lying peroneus brevis muscle belly is unrelated to an increased risk of peroneal tendon dislocations; nevertheless, additional data are needed.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

FundingThe authors declare that they have received no funding for the conduct of the present research, the preparation of the article, or its publication.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.