The purpose of this study is to identify which variables may have a significant impact in mid-term survivorship following hip arthroscopy.

MethodsThis a single-centre single-surgeon retrospective study including 102 patients who underwent a hip arthroscopy procedure between August 2007 and October 2011.

Each subject completed three questionnaires at final follow- up: “Hip "Outcome Score-Activities of Daily Living" (HOS-ADL), "Hip Outcome Score-Sport" (HOS-S) and " Modified Harris Hip Score “(m-HHS).

ResultsThirty-nine patients (40 hips) were finally included in our study. Mean age was 43.1 ± 9.9 years with a three-year minimum follow-up (75.43 ± 25.2 months).

Younger patients and those with a shorter duration of symptoms obtained significantly higher HOS-S and m-HSS scores. Patients who had undergone previous lumbar spinal surgery obtained significantly worse HOS-ADL scores.

Patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) was achieved in 23 patients (57.5%) for m-HHS, 22 patients (55%) for HOS-ADL and 25 patients for HOS-S scores.

No major complication was observed. Only four patients had minor complications.

Mean survival time was 97.1 months (95% CI, 85.1–109.1 months), with a survival at 8 years of 69% (95% CI, 53%–85%).

ConclusionsOur findings suggest that hip arthroscopy is a safe procedure with acceptable functional outcomes after a long follow-up. Care should be taken when treating patients with prior lumbar surgery.

Level of evidenceLevel IV. Case series.

El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar qué factores pueden influir en la supervivencia de la artroscopia de cadera a medio plazo en el contexto de patología degenerativa.

Material y métodosLlevamos a cabo un estudio retrospectivo de 40 casos de una serie de 102 pacientes intervenidos de artroscopia de cadera en nuestro centro, desde agosto de 2007 a octubre de 2011.

Al final del seguimiento, todos los pacientes cumplimentaron 3 escalas funcionales: "Hip "Outcome Score-Activites of Daily Life" (HOS-ADL), "Hip Outcome Score-Sport" (HOS-S) y "Harris Hip Score modificado" (HHSm).

ResultadosFinalmente se incluyó un total de 39 pacientes (40 caderas), con una edad media de 43,1 años y un tiempo de seguimiento medio de 6 años (43 meses -130 meses).

Los pacientes intervenidos con una edad inferior a 50 años de edad obtuvieron mejor puntuación en las escalas HOS-S (25,2 puntos) y HHS-m (84.1 puntos) en comparación a aquellos intervenidos a partir de dicha edad (HOS-S [25,2 puntos]; HHS-m [84.1 puntos]). El tiempo de evolución también influyó significativamente en el resultado de nuestros pacientes, siendo mejor en aquellos en los que éste era menor a 12 meses (26.6 meses), en comparación con aquellos en los que era mayor (21,3 meses).

Por otro lado, aquellos que presentaban una intervención quirúrgica lumbar previa obtuvieron peores resultados de HOS-ADL (49,3 puntos), respecto a aquellos que no presentaban este antecedente (56,5 puntos).

El Patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) fue superado por 23 pacientes (57,5%), 22 pacientes (55%) y 25 pacientes (62,5%) en las escalas HHSm, HOS-ADL y HOS-S respectivamente.

Ningún paciente presentó ninguna complicación mayor. Cuatro pacientes presentaron complicaciones menores.

La supervivencia media obtenida fue de 97,1 meses (IC 95%, 85,1–109,1 meses), asociado a un 81% de pacientes (IC 95%, 69%–93%) que no precisó rescate quirúrgico a los 10 años.

ConclusionesCreemos que los datos obtenidos en nuestra serie sugieren que la artroscopia de cadera en el contexto de patología degenerativa es una intervención quirúrgica segura con un resultado funcional fiable a corto-medio plazo. Por otro lado, dicha indicación debería con mayor precaución en pacientes sometidos previamente a cirugía lumbar.

Nivel de evidenciaNivel IV. Serie de casos.

It was Ganz1 who, in 2003, first described the concept of Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI) as a cause of early onset hip arthritis in young non-dysplastic patients. Although at first it was described as a diagnostic tool,2 hip arthroscopy is now considered in many hospitals to be the treatment of choice for FAI.3–5 This is due to the functional results that have been seen in the last decade, as they are comparable with open techniques and are also associated with a low rate of morbidity and complications.6,7 This technique also reduces the recovery time and the delay in patients recommencing their usual activities.8 In fact, this entity is now the most frequent indication for hip arthroscopy.9–11

On the other hand, it has to be pointed out that the majority of the series reviewed to date analyse the results with an average follow-up time of around two or three years,5–21 and this restricts knowledge of the results of this type of intervention over the medium to long term.

Our hypothesis is that arthroscopic hip surgery due to degenerative pathology has a high survival rate over the medium term.

Based on the above consideration, we analyse the functional result and survival of hip arthroscopy within the context of degenerative pathology.

Material and methodsWe undertook a retrospective study of a series of 102 patients who had been subjected to arthroscopic hip intervention in our hospital, within the context of degenerative hip pathology; the intervention in all cases was by the same surgeon (E. R. L. C.), and took place from August 2007 to April 2016.

Inclusion criteria: patients older than 18 years of age subjected to primary arthroscopic hip surgery after showing symptom relief with intra-articular infiltration, operated by the same surgeon (E.R.L.C.), with a postoperative follow-up of at least three years.

Exclusion criteria: patients under the age of 18, ipsilateral primary surgery, the absence of preoperative intra-articular infiltration, or loss during follow-up.

Of the 63 patients excluded, 25 were lost during follow-up, three patients were under the age of 18 years old at the time they were operated, 11 patients had been subjected to previous surgery, 17 patients did not wish to take part in the study, and the seven remaining patients had not been treated with intra-articular infiltration prior to surgery.

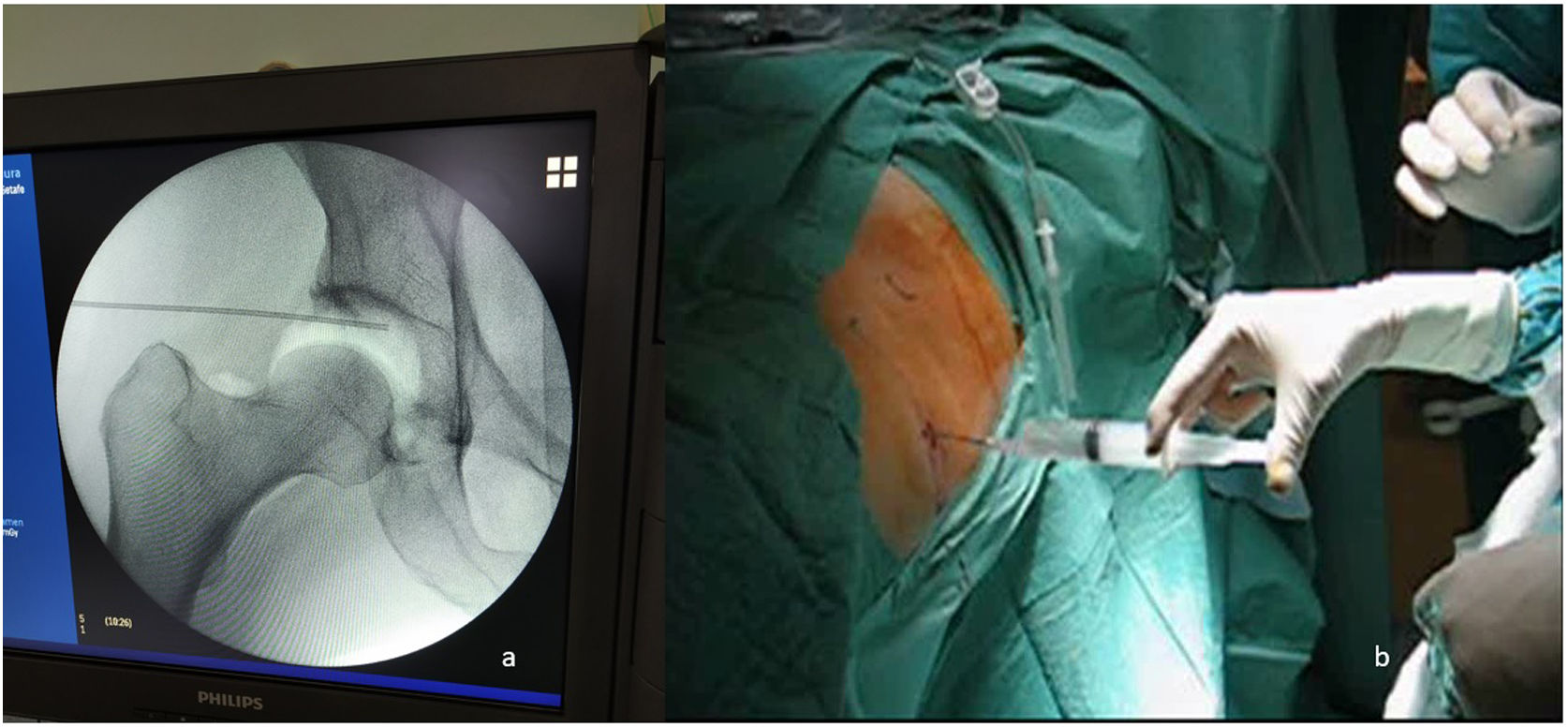

At the moment surgery was indicated, an intra-articular infiltration was carried out in the surgery under sterile technique, with 1 cc Celestone and 2 cc Bupivacaine 0.25% in all of the patients. This was to assess the possible intra-articular origin of the symptoms, as well as to evaluate the possible improvement due to arthroscopic hip surgery (AHS).22The average time from infiltration to surgery was 4.7 months (2.8–9.1 months).

Demographic data were recorded, such as: age at the time of surgery, sex, laterality, the time during which the symptoms had evolved, the presence of labrum rupture in nuclear magnetic arthro-resonance (NMarthroR) prior to surgery, the appearance of symptoms during sitting or walking, or exploratory manoeuvres that triggered pain at the moment prior to surgery (impingement, apprehension, resisted hip flexion test or FABER).23 Radiographic data were also recorded (Tönnis24 or type of FAI25) and the surgical procedure (traction time; technique used on the acetabulum, femoral neck or the labrum; as well as the presence or not of a chondral lesion).

To establish the type of FAI of each one of our patients we performed a simple radiographic study of all of them, including three views: anteroposterior view (AP) of the pelvis, axial view of the hip and Dunn’s modified axial view. We determined there was a CAM type FAI when we observed an alpha angle greater than 55° in a Dunn axial X-ray,25 while a centrolateral Wiberg angle above 40° in an AP view of the pelvis was defined as PINCER type FAI.25

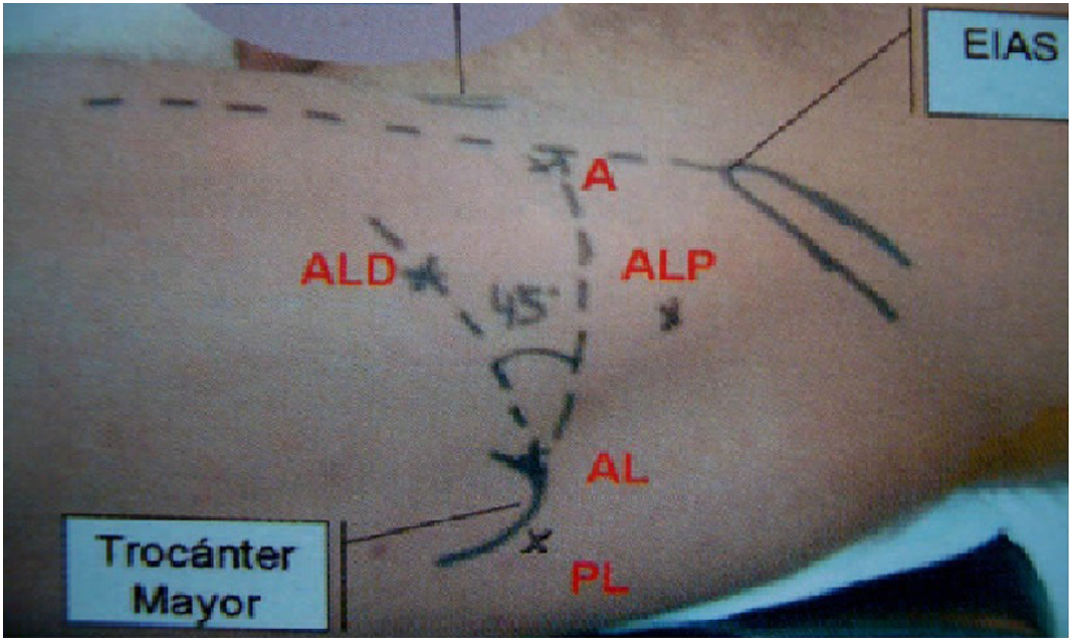

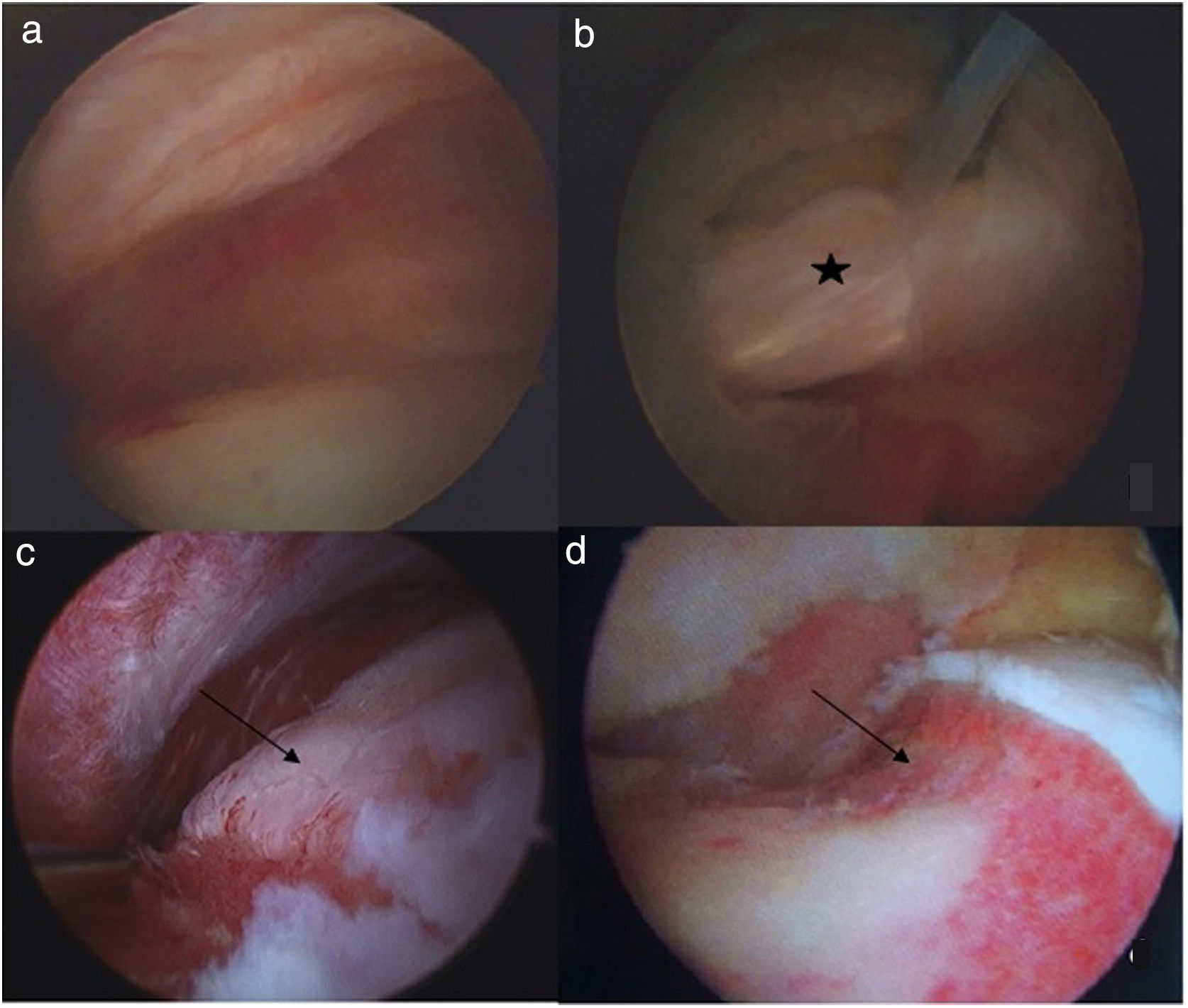

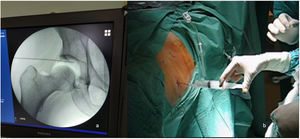

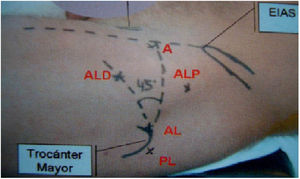

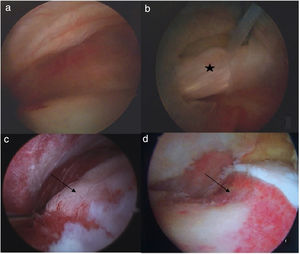

All Inside26 technique was used for all of the patients. An intraoperative visually controlled aerogram was used to check the increase in intra-articular space with traction (Fig. 1). We then release the traction until the moment of commencing the intervention, thereby reducing the total duration of the same. Using three portals (anterolateral, anterior and distal anterolateral or modified distal anteromedial of the hip)26 (Fig. 2), we approach the acetabulum and proximal femur, in the central compartment as well as in the peripheral compartment (Fig. 3). We perform an interportal capsulotomy to easily access the central compartment, adding a T capsulotomy only in those cases where we associate femoral osteoplasty in the peripheral compartment.27 This is closed in an individualised way, depending on the patient and based on the surgeon’s judgement.28

On the other hand, we add arthroscopic psoas release only in those patients with internal projection or impingement associated with labral rupture,29 although always at the final moment of the intervention, to reduce the risk of complications.29

Postoperatively we permit immediate partial loading with two crutches during 15 days in all of our patients, only restricting maximum ranges of external rotation in joint mobility. If we make microperforations in the acetabulum (grade II-III chondral lesion on the Outerbridge scale30), we prescribe not loading the limb during 15 days. Once the stitches have been removed, we encourage the practice of sports without axial loading (chiefly swimming and cycling), permitting the gradual inclusion of normal physical activity after the third month.

All of the patients were interviewed at the end of their follow-up period by the first author (T. P. D.) and they filled out three functional level surveys: the Hip Outcome Score-Activities of Daily Life (HOS-ADL), the Hip Outcome Score-Sport (HOS-S) and the mHHS. As an author has described previously,31 we eliminate elements that refer to deformity and range of movement from the last scale, as none of them affects the indication for hip arthroscopy.

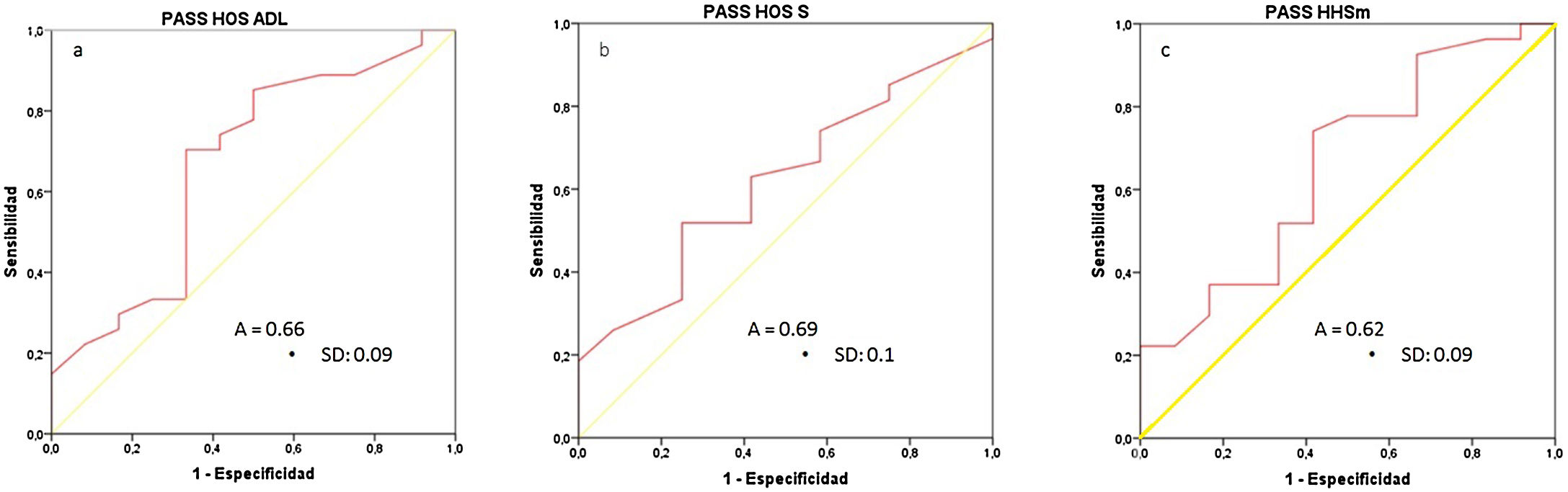

The binominal question defined by Tubach et al.32 in 2005 was used to determine patient satisfaction at the said moment in time. We used statistical analysis of ROC curves to establish the Patient acceptable symptom state (PASS)33 for the different functional scales.

We used version 22 of the SPSS for the analytical study. Previous analysis using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov method showed an abnormal distribution in our sample, we used the Mann-Whitney U test for the relationship between independent qualitative and quantitative variables, as well as Fisher’s exact test for the relationship between independent qualitative variables. P < .05 was taken as the cut-off point for considering a difference to be statistically significant.

We also calculated survival and the percentage of patients free of surgical rescue after 2, 5 and 10 years, using the Kaplan-Meier method. We use surgical rescue (arthroscopic as well as by prosthesis) and radiographic progression of arthrosis according to the Tönnis scale as cut-off points in the follow-up.

ResultsA total of 40 hip arthroscopies (39 patients), carried out from August 2007 to October 2011, were finally included in the study. The average age of the patients at the time of surgery was 43.1 ± 9.9 years, and all of them were followed up for at least three years (75.4 ± 25.2 months; range: 43−130 months). The right side predominated slightly in our series (25 interventions; 62.5%) as did male sex (20 patients; 51.3%). The women were slightly older at the time of surgery than the men, without this being statistically significant (43.7 years in the women vs. 46.2 years in the men; P = .49).

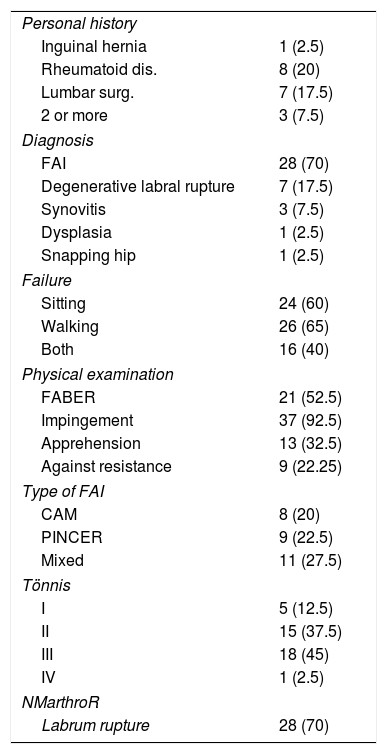

Table 1 shows the clinical and radiographic data that were collected, while the data relating to surgical procedures are shown in Table 2.

Clinical and radiological data.

| Personal history | |

| Inguinal hernia | 1 (2.5) |

| Rheumatoid dis. | 8 (20) |

| Lumbar surg. | 7 (17.5) |

| 2 or more | 3 (7.5) |

| Diagnosis | |

| FAI | 28 (70) |

| Degenerative labral rupture | 7 (17.5) |

| Synovitis | 3 (7.5) |

| Dysplasia | 1 (2.5) |

| Snapping hip | 1 (2.5) |

| Failure | |

| Sitting | 24 (60) |

| Walking | 26 (65) |

| Both | 16 (40) |

| Physical examination | |

| FABER | 21 (52.5) |

| Impingement | 37 (92.5) |

| Apprehension | 13 (32.5) |

| Against resistance | 9 (22.25) |

| Type of FAI | |

| CAM | 8 (20) |

| PINCER | 9 (22.5) |

| Mixed | 11 (27.5) |

| Tönnis | |

| I | 5 (12.5) |

| II | 15 (37.5) |

| III | 18 (45) |

| IV | 1 (2.5) |

| NMarthroR | |

| Labrum rupture | 28 (70) |

Values are shown as an accumulated number (% of the total). Rheumatoid dis., rheumatoid disease; Lumbar surg., previous lumbar surgery; FAI, femoroacetabular impingement; FABER, flexion, abduction and external rotation; NMarthroR, nuclear magnetic arthro-resonance.

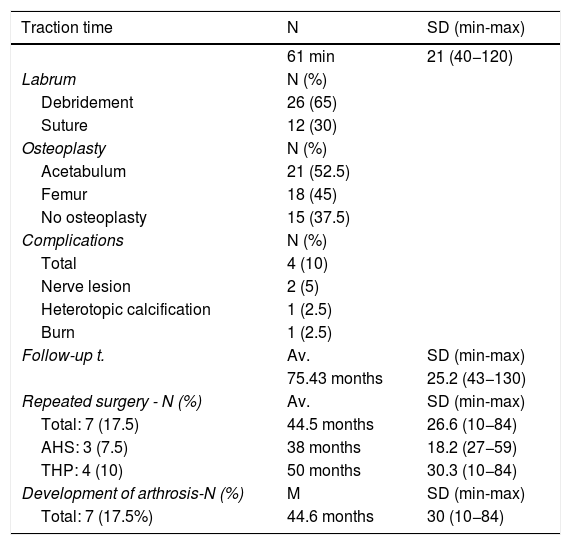

Surgical procedure data.

| Traction time | N | SD (min-max) |

|---|---|---|

| 61 min | 21 (40−120) | |

| Labrum | N (%) | |

| Debridement | 26 (65) | |

| Suture | 12 (30) | |

| Osteoplasty | N (%) | |

| Acetabulum | 21 (52.5) | |

| Femur | 18 (45) | |

| No osteoplasty | 15 (37.5) | |

| Complications | N (%) | |

| Total | 4 (10) | |

| Nerve lesion | 2 (5) | |

| Heterotopic calcification | 1 (2.5) | |

| Burn | 1 (2.5) | |

| Follow-up t. | Av. | SD (min-max) |

| 75.43 months | 25.2 (43−130) | |

| Repeated surgery - N (%) | Av. | SD (min-max) |

| Total: 7 (17.5) | 44.5 months | 26.6 (10−84) |

| AHS: 3 (7.5) | 38 months | 18.2 (27−59) |

| THP: 4 (10) | 50 months | 30.3 (10−84) |

| Development of arthrosis-N (%) | M | SD (min-max) |

| Total: 7 (17.5%) | 44.6 months | 30 (10−84) |

Values are shown as N, accumulated value; Av., average time in months; %, percentage of total. SD, standard deviation; min-max, range defined by its minimum and maximum values; min, minutes; T. Follow-up time; AHS, arthroscopic hip surgery; THP, total hip prosthesis.

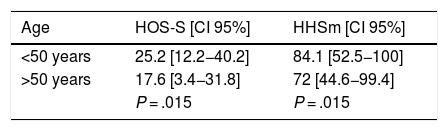

The final scores on the different functional scales were: 81.3 points (pts.) (SD: 16 pts., range: 47–100 pts.) HHSm; 55.2 pts. (SD: 9.6 pts., range: 36–68 pts.) HOS-ADL; 23.5 pts. (SD: 8 pts., range: 9–36 pts.) HOS-S. We found a statistically significant difference between the scores obtained by our patients on these scales based on factors such as age at the time of surgery, the length of time over which symptoms evolved and a history of previous lumbar surgery (Table 3).

Factors that influence the results obtained in the functional scales.

| Age | HOS-S [CI 95%] | HHSm [CI 95%] |

|---|---|---|

| <50 years | 25.2 [12.2−40.2] | 84.1 [52.5−100] |

| >50 years | 17.6 [3.4−31.8] | 72 [44.6−99.4] |

| P = .015 | P = .015 |

| Evolution t. | HOS - S [CI 95%] |

|---|---|

| <12 months | 26.6 [22.6−40.6] |

| >12 months | 21.3 [5.1−37.5] |

| P = .04 |

| Previous lumbar surg. | HOS-ADL [CI 95] |

|---|---|

| Yes | 49.3 [35.5−63.1] |

| No | 56.5 [37.1−75.9] |

| P = .049 |

Values on the functional scales are shown in points. HOS-S, Hip Outcome Scale-sport; HHSm, modified Harris hip score; HOS-ADL, Hip Outcome Scale-Activities of Daily Life; CI, confidence interval; Evolution t., time over which symptoms evolved.

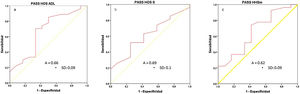

We calculate the PASS value on the different functional scales by using COR curves (Fig. 1): PASS HOS - ADL: 53.5 pts. (sensitivity [S]:70%/specificity [E]: 67%); PASS HOS - S: 22.5 pts. (S: 63%/Sp: 62%); PASS HHSm: 77.4 pts. (S: 74%/Sp: 59%), Fig. 4.

COR curves of the functional scales, values expressed at the power of 10−2. A) PASS HOS ADL (acceptable patient symptomatic state on the Hip Outcome Scale-Activity of Daily Life scale). B) PASS HOS S (acceptable patient symptomatic state for the Hip Outcome Scale-Sport scale). C) PASS HHSm (acceptable patient symptomatic state for the Harris Hip Score modified scale). A, area under the curve; SD, standard deviation.

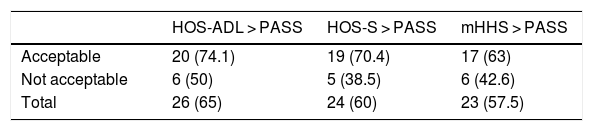

We recorded which patients in our series scored higher than the PASS value for the different scales (Table 4). We found there was a statistically significant difference in the number of patients who reached the PASS value on the HOS-S scale in terms of the time over which their symptoms had evolved prior to the operation. 66.7% of those patients whose symptoms had evolved over less than 12 months reached the PASS value (12 patients of 18); vs 37.5% (10 patients of 27) whose symptoms had evolved over longer than 12 months [P = .049].

Functional scale PASS values.

| HOS-ADL > PASS | HOS-S > PASS | mHHS > PASS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptable | 20 (74.1) | 19 (70.4) | 17 (63) |

| Not acceptable | 6 (50) | 5 (38.5) | 6 (42.6) |

| Total | 26 (65) | 24 (60) | 23 (57.5) |

This shows the total number of patients (and percentage respecting the patients in the stratum) that score higher than the PASS value on the different scales. The division between acceptable or not acceptable is based on the response of the patients to the question described by Tubach32 HOS-ADL > PASS, the value of the Hip Outcome Scale-Activities of Daily Life is higher than the established PASS value; HOS-S > PASS, the value of the Hip Outcome Scale-Sport is higher than the established PASS value; HHSm > PASS, the value of the modified Harris Hip Score scale is higher than the established PASS value.

On the other hand, we found a statistically significant difference in the time over which symptoms had evolved between those patients who had a preoperative FABER + (19.5 ± 10.4 months) and those who had not (16 ± 13.1 months) [P = .035]; as well as between those patients who had been subjected to acetabulum osteoplasty (22.4 ± 12.2 months) compared with those who had received a labral suture (10.9 ± 6.6 months) [P = .002].

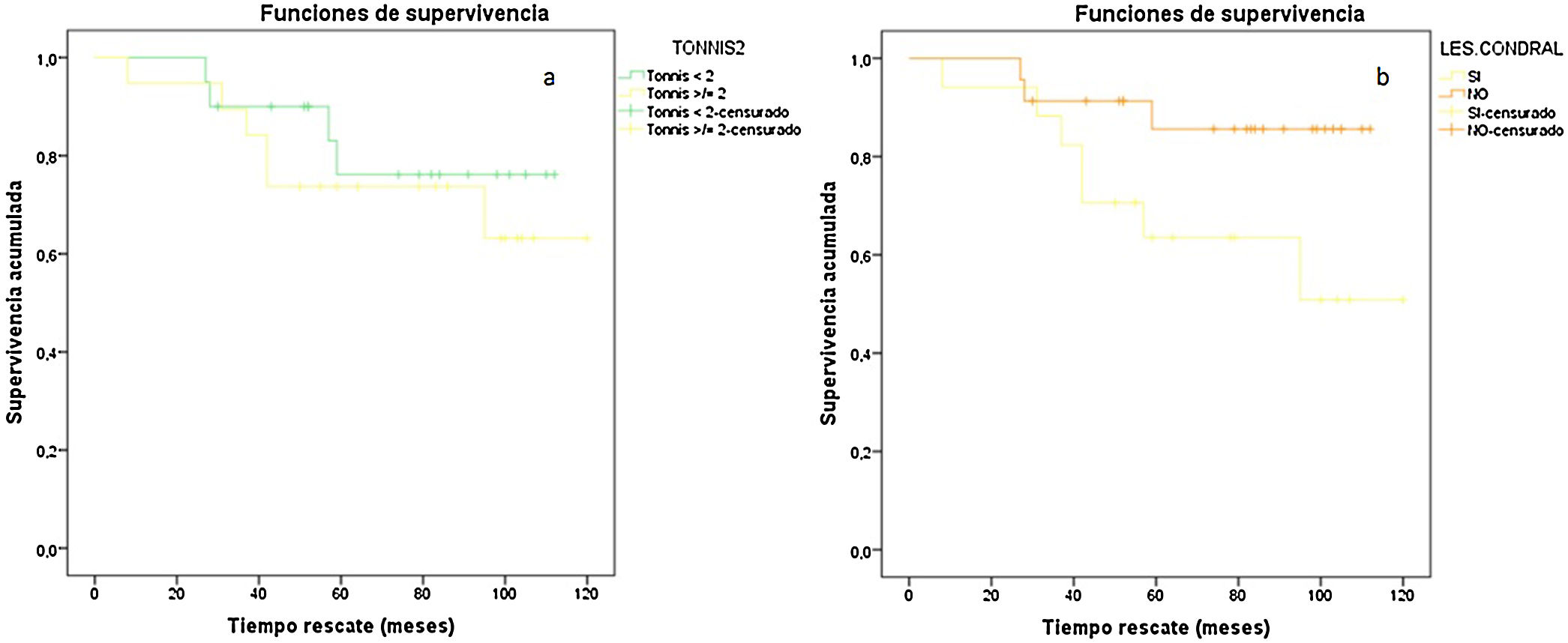

We also found a statistically significant difference in the time our patients took to return to work, based on their preoperative Tönnis grade (Tönnis 0–I: 14.5 ± 6.9 weeks vs. Tönnis II–III: 9.4 ± 3.8 weeks [P = .006]); as well as if a chondral ulcer on the acetabulum had been detected intraoperatively (patients with a chondral ulcer: 9 ± 7.6 weeks vs. patients without a chondral ulcer: 13.7 ± 6.8 weeks [P = .01]). Paradoxically, those patients who were found to have a chondral ulcer had a poorer score on the HOS-S scale at the end of the follow-up (patients with a chondral ulcer: 20.1 ± 7.6 pts. vs. patients without a chondral ulcer: 25.7 ± 7.2 pts. [P = .04]). No statistically significant differences were found in our series that linked radiological findings prior to the surgical operation or the type of operation performed with the score obtained in the different functional scales at the end of follow-up, or the need for another surgical operation (Fig. 5).

Survival curves according to Tönnis and the presence of a chondral ulcer, values expressed to the power of 10−2. A) Survival curve according to Tönnis. COR of functional scales. B) Survival curve according to the presence of a chondral ulcer. Tönnis < 2, 0–I; Tönnis ≥ 2, II–III; Chondral les., presence of chondral lesion.

No major complications were recorded in the whole series (deep infection, fracture or proximal femur necrosis, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, or intra-abdominal extravasation of liquid), and there were only four minor complications (Table 2).

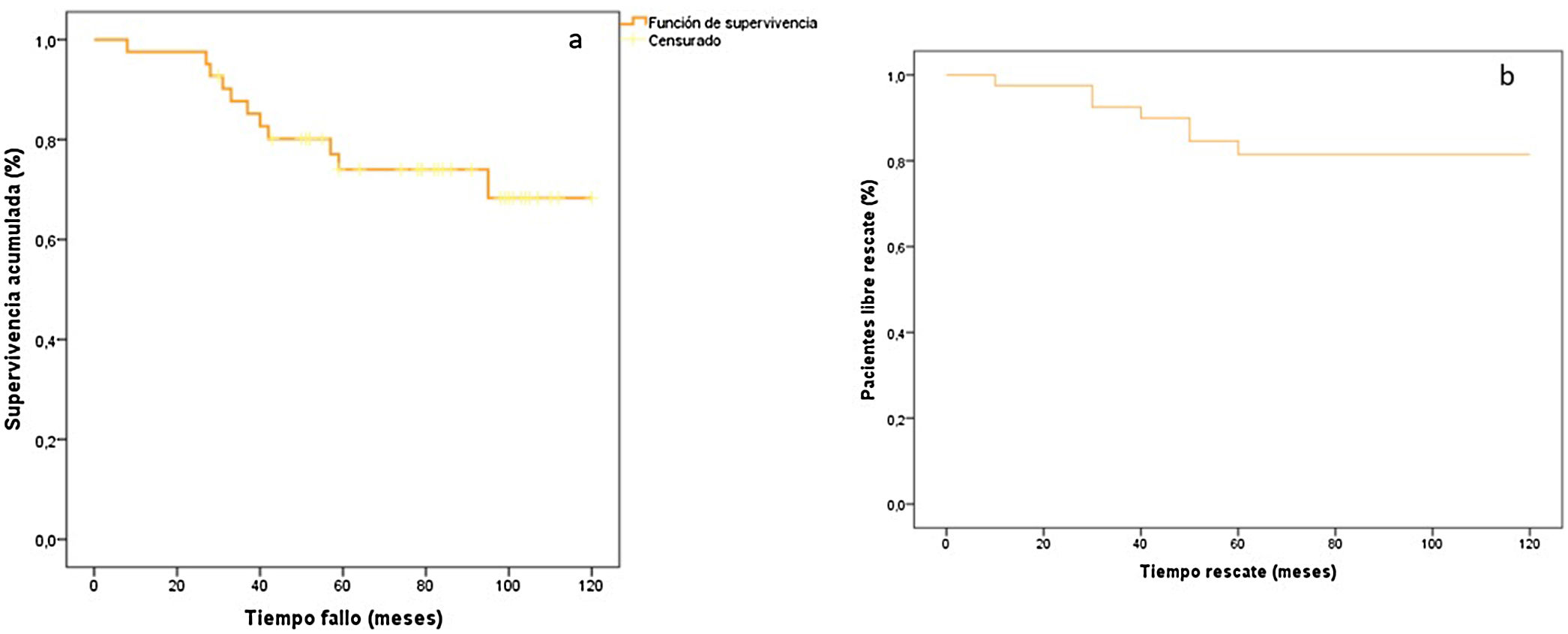

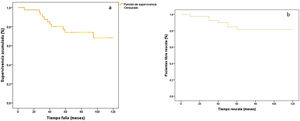

The Kaplan-Meier method (Fig. 6A) showed an average survival of 97.1 months (CI 95%: 85.4–108.8).

Kaplan-Meier curve, accumulated survival (%). A) Number of patients without progress of arthrosis according to the Tönnis scale,24 between two consecutive visits or rescue surgery, expressed as a percentage. Time to failure (months): time to the appearance of progress in arthrosis according to the Tönnis scale,24 between two consecutive visits or rescue surgery, expressed in months. B) Accumulated survival curve, patients with no rescue surgery, expressed as a percentage. Rescue time (months): time to the performance of rescue surgery, expressed in months.

On the other hand, 81% of our patients (CI 95%, 69%–93%) had required no rescue surgery after 19 years. This percentage rises to 85% (CI 95, 75%–95%) at five years and up to 92% (CI 95%, 66%–98%) at two years (Fig. 6B).

DiscussionIn this work we present the functional results of arthroscopic hip surgery performed in our hospital in the context of degenerative pathology, with an average follow-up of 76.4 months. The majority of previous series5,12,15 and reviews11,13,17–21,34 have short follow-up periods of around two to three years. As far as we know, this is one of the series with the longest follow-up times registered in the current bibliography.4,30,34

In the same way as was described by Levy et al.11 in their 2016 review, we found a statistically significant difference in the final functional result for our patients on the HHSm and HOS-S scales, based on their age at the time of surgery. This author also mentioned differences in his results based on the level of patients prior to surgery on the Tönnis scale. As it the case with other authors,34–36 we did not find this. We also found a statistically significant difference in our patients’ results on the HOS-S scale, depending on the duration of their symptoms prior to surgery. This agrees with the results published by Basques et al.,15 as does the fact that those patients whose symptoms had evolved over a shorter time had a higher probability of scoring higher than the PASS value for the HOS-S scale.15 This is why many authors recommend performing AHS before the symptoms have lasted for six or nine months,5–12 as the persistence of symptoms may lead to the appearance of degenerative changes, because chondral lesions give rise to a poorer prognosis for our intervention33–35 and the risk of a rescue prosthesis increases.14,28,35–38 All of these factors may justify the fact that FABER + patients prior to surgery had a longer duration of symptoms.

In our series, the patients who had an acetabular chondral ulcer showed a poorer functional result than those who did not have one. Nevertheless, we found no association between the Tönnis grade prior to surgery in our patients and the functional result at the end of follow-up. On the other hand, as far as we know no other series describes a probable association between previous lumbar surgery and the final results of AHS. It has to be said that lumbar pathology involves a basic differential diagnosis in any pathology, be it intra-articular of the hip or peritrochantheric.23

It is striking that the patients with the highest Tönnis grade prior to surgery and those in which a chondral lesion was detected recommenced their working activity earlier. This is in spite of the fact that both factors are widely described in the literature as unfavourable prognostic factors for interventions of this type.11,14,18,19,35,36 This finding cannot be compared to what has been published beforehand, given that, although the return to sports activity has been widely discussed in the current bibliography, the socioeconomic outlook and return to work have hardly been evaluated in the literature.37

Our revision rate of 17.5% (THP: 10%/AHS: 7.5%) is comparable with and even higher than series published before ours.14,19,20,35 Philippon et al.,35 who performed a series of 96 AHS in patients whose demographic data are similar to those of ours (older than 60 years and 60% Tönnis I or II prior to surgery), give a far higher THP rescue rate than ours, at 42% after an average follow-up time of 54 months. For their part, Gupta et al.14 and Newman et al.20 obtained an arthroscopic revision rate of around 8%, with an average follow-up of two years. Recently, in 2015 Domb et al.19 undertook a review which cites an 8% arthroscopic rescue rate in AHS with an average follow-up of 42 months.

The average survival we obtained at the end of the series was 97.1 months (CI 95%: 85.4–108.8),with a percentage of patients who had had no rescue surgery after 2, 5 and 8 years of 92%, 85% and 81%, respectively. These results are better than those given by McCarthy et al.36 and Haefeli et al.4, who reported 75% of patients with no rescue surgery after five years and 81% after seven years, respectively. On the other hand, other authors14 recorded similar survival rates to ours over a shorter period of time, at up to 90.8% at two years. All of these series were composed of patients who were never old than 40 years, and this may add to the value of our results, given that age is widely documented as a risk factor for early rescue surgery in AHS.14,16,31,38

Lastly, it should be underlined that we recorded no major complications throughout the series, and there were only four minor complications (10%). Two patients had neurological lesions (5%), and both neuroapraxias had completely recovered after six months; one patient (2.5%) developed heterotopic ossifications during radiological out-patient follow-up, and this was managed conservatively. These results are smaller amounts than those recorded in recent published reviews,16–18,21 as these describe approximately 1%–2% of neurological lesions, almost all of which were self-limiting neuroapraxias,16,17,21 which is similar to our series; and 1% heterotopic ossifications.18 On the other hand, the majority of these reviews are based on series treated in referral centres with a high annual volume of AHS. The series by Larson et al.39 in a tertiary hospital, obtained a total of 8% complications, similar to the level we recorded.

LimitationsOne of our main limitations is that this is a retrospective study undertaken in a single centre with a small sample size, although the latter is similar to several series published beforehand.4,13,31 We also have a high rate of patient loss during follow-up. This may be due to a demographic stratum that is highly variable in terms of occupation and residence, as another author mentioned in the past.36 We accept that this may have caused a selection distortion.

We have no control group or preoperative scales of our same cohort to use in a comparative study at the end of follow-up. To counterbalance this situation we analyse the PASS value as well as the percentage of patients in our series that surpassed this value. In this way we are able to determine how many patients had a good subjective functional state at the end of follow-up.33

On the other hand, the cut-off points established during the statistical study of our results were chosen at random, following the tendency set by previously published papers on AHS.15 Nor did we record the grade of the chondral lesions observed in our patients intraoperatively or their location; we only state whether or not there were any. Nor do we supply a pain measurement scale for our patients.

ConclusionsThis series of AHS has one of the longest follow-up periods recorded in the current bibliography, and it is also the second survival analysis in terms of the duration of follow-up to be published.4 We find an acceptable level of safety in the results of our procedures, with acceptable functional results and an average survival time longer than 90 months.

It should also be pointed out that this is the first work to cover the relationship between lumbar pathology and the results of AHS, and this may be useful for surgeons when deciding on the indication for the same.

We therefore believe that our hypothesis is confirmed: arthroscopic hip surgery due to degenerative pathology has a high survival rate over the medium term.

Some clinical and demographic factors, such as the time over which symptoms have evolved and patient age, are widely recognised in the literature as decisive factors for the functional result of AHS. In particular, we believe that if there has been previous lumbar surgery, the surgeon should be cautious when indicating AHS.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments on human beings or animals took place for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their centre of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this paper.

FinancingThis work was not financed.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Torres-Perez D, Escribano-Rueda L, Lara-Rubio A, Gomez-Rice A, Delfino R, Martin-Nieto E, et al. Resultados funcionales y supervivencia a ocho años de la artroscopia de cadera en pacientes con patología degenerativa de cadera. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recot.2020.05.004