Since arthroscopy remains a controversial treatment of hip dysplasia, our objective was to analyse its clinical and radiological results in a cohort of patients with dysplasia and compare them to controls with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI).

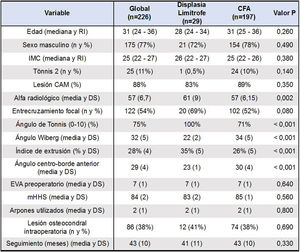

Material and methodsWe retrospectively analysed a series of patients who underwent hip arthroscopy for the treatment of labral pathology; 29 of them with borderline hip dysplasia and 197 with FAI, comparing reoperations and joint survival. The diagnosis of borderline dysplasia was made with a lateral centre-edge angle greater than 18° but less than 25°. The average follow-up was 43 months. We performed a multivariate regression analysis to evaluate the association of reoperations with different demographic, radiological and intraoperative variables.

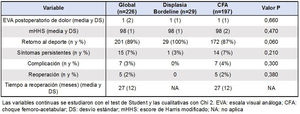

ResultsSeven complications were registered in the FAI group (1 medically treated superficial wound infection, 3 pudendal nerve paraesthesias, 1 deep vein thrombosis and 2 heterotopic ossifications) and none in the dysplasia group. While 5 patients from the FAI group required a new surgery, none of the dysplasia group was re-operated (p=.38). After adjusting for confounders, reoperation showed a very strong association with the finding of osteochondral lesions during index surgery, with a coefficient of .12 (p<.001, 95%CI=.06-.17).

ConclusionHip arthroscopy was useful in the treatment of borderline dysplasia, without non-inferior survival compared to the FAI group. We suggest indicating it carefully in dysplasia cases, whenever the symptoms of femoroacetabular friction prevail over those of instability.

Puesto que la artroscopia de cadera es controversial en el tratamiento de la displasia, nuestro objetivo fue analizar sus resultados clínicos y radiológicos en una cohorte de pacientes con displasia limítrofe y compararlos con controles con choque femoro-acetabular (CFA).

Material y métodosAnalizamos retrospectivamente a un grupo de 29 pacientes con lesión labral secundaria a displasia limítrofe de cadera y a otro de 197 con CFA, ambos tratados con artroscopia, evaluando las re-operaciones y la supervivencia articular. El diagnóstico de displasia limítrofe se realizó con un ángulo centro-borde lateral mayor a 18° pero menor a 25°. El seguimiento promedio fue de 43 meses. Realizamos un análisis de regresión multivariada para evaluar la asociación de re-cirugía con distintas variables demográficas, radiológicas e intraoperatorias.

ResultadosSe registraron 7 complicaciones en el grupo CFA (1 infección superficial tratada médicamente, 3 parestesias de nervio pudendo, 1 trombosis venosa profunda y 2 casos de calcificación heterotópica) y ninguna en el grupo displasia. Mientras que 5 pacientes del grupo CFA requirieron una nueva cirugía, ninguno del grupo displasia fue reintervenido (p=0,38). Luego de ajustar por confundidores, la reoperación demostró una asociación muy fuerte con el hallazgo de lesiones osteocondrales, con un coeficiente de 0,12 (p<0,001, IC95%=0,06–0,17).

ConclusiónLa artroscopia de cadera resultó útil en el tratamiento de la displasia limítrofe, sin hallarse diferencias de supervivencia con el grupo CFA. Sugerimos indicarla en forma cuidadosa en la displasia, siempre que primen los síntomas de roce femoroacetabular por sobre los de inestabilidad.

Arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) with an associated labral lesion has shown very encouraging results in the medium and long term,1–3 with the supposed benefit of preventing further degeneration of the joint and thus avoiding the development of secondary osteoarthritis.4 However, the usefulness of hip arthroscopy in the treatment of intra-articular injuries associated with concomitant acetabular dysplasia is less clear.

Hip dysplasia is largely defined by radiographic parameters, including Tönnis angle (or acetabular index) greater than 10°, increased femoral anteversion, decreased anterior centre-edge angle (ACEA) less than 20°, and decreased Wiberg's lateral centre-edge angle (LCEA) less than 25°.5,6 Of these, the LCEA is most often used to detect dysplasia when analysing conventional anteroposterior pelvic x-rays. This measurement has been further sub-stratified, with severe dysplasia represented by an LCEA of less than 18° and borderline dysplasia represented by an LCEA of more than 18° but less than 25°. As a result of poor femoral head coverage, increased axial load is transmitted to the surrounding soft tissues, including the labrum and capsule, leading to compensatory hypertrophy of these structures, as they are recruited as secondary hip stabilisers. When these structures can no longer compensate for the excess force, they break starting a secondary degenerative joint process.7

Since the early 1990s, hip joint preservation surgery for dysplasia has been limited to open procedures, such as peri-acetabular osteotomy (PAO). PAO has reported good clinical and radiological results.8 According to Lerch et al., one third of PAOs successfully survive to 30year follow-up without degenerative progression or failure due to conversion to total hip replacement.9 In contrast, hip arthroscopy has been used primarily as an adjuvant procedure, performed in addition to PAO, with encouraging short-term results.10 However, isolated hip arthroscopy in the treatment of hip dysplasia has shown mixed results in the literature.11

Since its indication is controversial as a single treatment for dysplasia, our aim was to analyse the clinical and radiological results of arthroscopic treatment of a cohort of patients with borderline hip dysplasia and compare them with those of a control cohort of patients with FAI (non-dysplastic) who also underwent arthroscopic treatment, assessing the complications and joint survival of both groups.

Material and methodsA retrospective study was conducted of a consecutive group of patients with a diagnosis of labral lesion secondary to borderline hip dysplasia (group 1) and with FAI (group 2) treated with arthroscopy between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2015. Only patients with both diagnoses treated with hip arthroscopy and with a minimum follow-up of 2 years. Patients with coxa profunda or acetabular protrusion, patients without labral suture who only underwent labral debridement, revisions, those with dysplasia initially operated with PAO and those with previous ipsilateral hip disease such as local neoplasia, avascular necrosis, Perthes disease or epiphysiolysis were excluded. The median age was 31 and males predominated at 77% of the series. The median body mass index (BMI) was 25kg/m2. There were no significant differences in any of these 3 variables between the borderline dysplasia group and the FAI group. The average follow-up of the series was 43 months, with 41 months for group 1 and 43 months for group 2 (p=.33).

All the arthroscopies were performed by the same surgeon (FC). From a total 248 arthroscopies performed in the time period under study, 22 were excluded. Six patients were excluded because they were lost to follow-up after 12 months, one of whom met criteria for borderline dysplasia and the remaining 5 did not; however, all of them remained asymptomatic until the date of their last check-up. Three patients were excluded because they had a diagnosis of coxa profunda and two more because they had been treated in childhood for ipsilateral hip epiphysiolysis. Likewise, 11 patients in this series presented, at the time of the arthroscopic treatment, non-repairable labral lesions and were therefore debrided and excluded for this reason.

The demographic data as well as information on the functional progression of the series were obtained from the electronic clinical history database of our institution, which were collected prospectively. This data collection was carried out by 3 investigators, 2 of whom were not involved in the preliminary control of the patients.

The radiological study of the patients was by conventional anteroposterior pelvic x-rays and modified Dunn view with 45° of bilateral flexion taken with the patient in the supine position. We considered an anteroposterior pelvic x-ray acceptable when the coccyx was centred on the pubic symphysis, with a distance between 1 and 3cm and with symmetry of the obturator foramen to efficiently assess the acetabular version.5

The measurements routinely performed were as follows: Wiberg's angle, ACEA, alpha angle, sciatic spine sign, posterior wall sign and presence of cross-over sign.5,12 The Tönnis classification was used to assess the degree of joint degeneration.13 The diagnosis of pincer-type FAI consisted of the presence of at least 2 of the following: positive cross-over sign, presence of posterior wall sign, lateral centre-edge angle greater than 30°, positive sciatic spine sign, presence of acetabular os.14 Similarly, the diagnosis of cam-type FAI was made when there was an alpha radiological angle greater than 50° or a head-to-neck ratio of less than .8cm on the hip profile x-ray.15 In contrast, the diagnosis of borderline dysplasia was made in cases of an LCEA greater than 18° but less than 25°, with a femoral head extrusion index of at least 30%.6,16 Neither anterior nor posterior acetabular coverage was evaluated as a criterion for dysplasia in this series.6,17

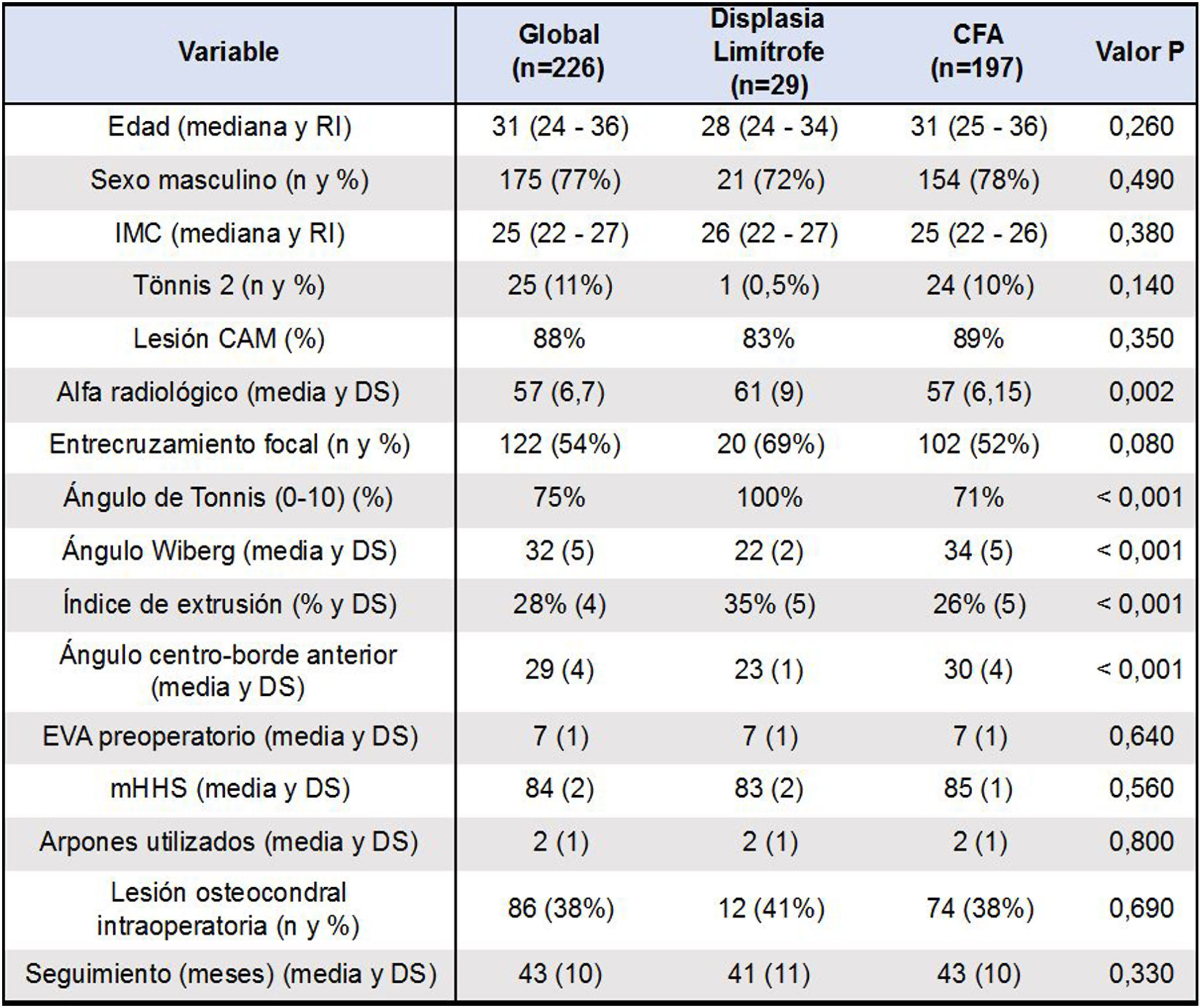

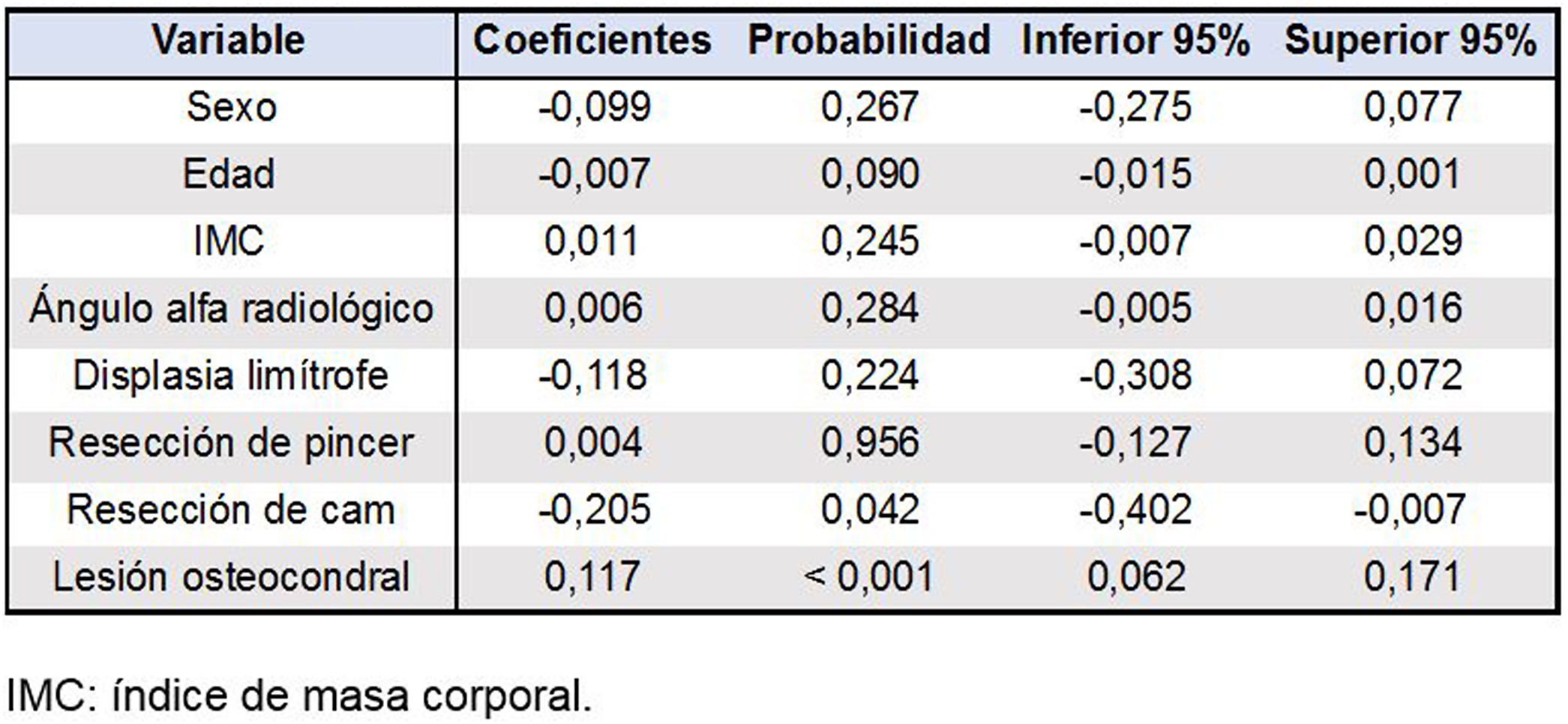

Although there was a higher proportion of Tönnis 2 degenerative changes among the patients with FAI (10%) than in the borderline dysplasia group (.5%), this difference was not significant. Both groups had a high prevalence of cam-type lesions (88% of the series). However, the value of the radiological alpha angle was higher in the borderline dysplasia group (61) than in the FAI group (57°) (p=.002). The Tönnis angle was categorised as normal (0°-10°) in all the patients with borderline dysplasia and in 71% of the FAI group, being less than 0° (p<10.001) in the rest of the latter group. The average LCEA was 22° in the patients with borderline dysplasia and 34° for those with FAI (p<.001); while the anterior centre-edge angle was 23° in the first group and 30° in the second (p<.001). The femoral head extrusion index was significantly higher in the dysplasia group compared to the FAI group (35% vs. 26%, p<.001) (Table 1).

Without using a universal imaging protocol, the labral and osteochondral lesions were further analysed by magnetic resonance18 and computerised axial tomography. Femoral and acetabular versions were not usually measured in these complementary studies.

The general indications for surgical treatment consisted of failure to respond to conservative treatment for at least 3 months’ disease course including 6 weeks of treatment with physiokinesiotherapy,19 joint blocks or poor patient-reported pain management despite the symptoms being present over a shorter period of time. In specific cases of dysplasia, arthroscopic treatment was indicated in the presence of positive symptoms for FAI and the absence of symptoms compatible with instability (negative apprehension test in hip hyperextension).20 Symptoms compatible with FAI were evidenced by a positive flexion-adduction-internal rotation test, combined with a positive internal rotation foot progression angle walking test (internal FPAW).21

The surgical technique consisted of traditional practice with the patient in the supine position on a radiolucent traction table, with padded protection of genitals and feet. The contralateral lower limb was positioned in abduction and subtle countertraction. The classic anterolateral and mid-anterior arthroscopic portals were used under radioscopic control, using a 70°-arthroscope.

Osteochondral lesions were assessed intraoperatively with the Outerbridge22 classification, measuring the size of the lesion with the 5mm hook palpator. In the case of a chondral lesion, microfractures were performed to revitalise the fibrocartilaginous tissue. The integrity of the chondrolabral junction was checked intraoperatively. The labrum was identified and spared without disinsertion in cases with chondrolabral junction integrity,23 using a 5.5mm high-speed lathe to remove over-coverage of bone under radioscopy. In contrast, in cases of chondrolabral junction rupture, the labrum was completely disinserted to then repair and stabilise it.24 After acetabuloplasty, the labrum was fixed to the remaining bone using 3.2mm (Arthrex®) harpoons. The number of harpoons used for labral fixation depended on each specific case with no previous protocol. Capsulotomy repair was not performed in any of the cases.

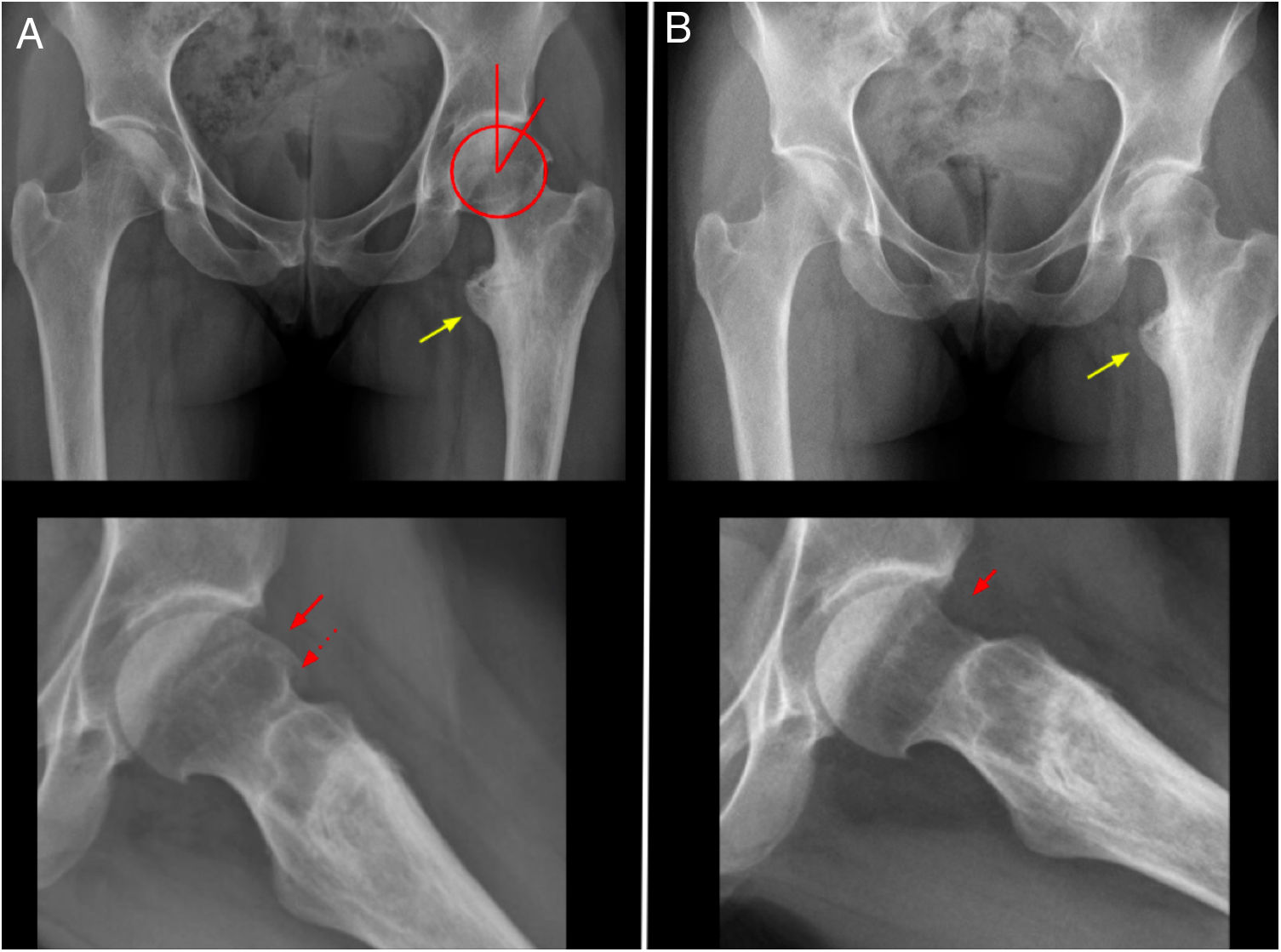

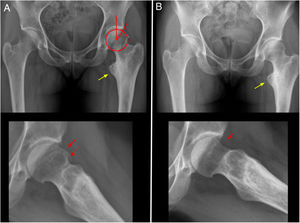

In the cases of FAI, the capsulotomy was interportal. In the cases of borderline dysplasia, arthroscopic capsulotomy was minimal, respecting the iliofemoral ligament and without connecting the 2 portals. The psoas tendon was not released in any case and no acetabular bone resection was performed.25 Capsulorrhaphy was not performed in any of the dysplasia cases, considering that a punctiform capsulotomy was made. In 83% of the cases of dysplasia there was an associated cam lesion, in which the lesion was resected by radioscopic control in the same way as in the cases of the FAI group (Fig. 1).

32-year-old female patient. A) Pre-operative antero-posterior X-ray and profile; LCEA=25°; Tönnis angle=10°; alpha angle=80°. Yellow arrow: coxa valga and extra rotation; continuous red arrow: cam- type deformity; dotted red arrow: ring osteophyte (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

The rehabilitation protocol consisted of non-weight bearing with crutches during the first 2 postoperative weeks, performing hip mobility exercises with flexion limited to 90°, neutral internal rotation, 30° external rotation and 30° abduction exercises for 3–6 weeks. Patients with microfractures were protected from weight bearing for 6 weeks. Return to sport was indicated between 3 and 6 months postoperatively depending on the muscle strength recovered.

The pre- and postoperative modified Harris Hip score (mHHS) and the pre- and postoperative pain visual analogue scale (VAS) were used to analyse clinical progression. We considered revisions or joint failures as reoperations performed to correct unwanted sequelae from previous surgery,26 analysing the type of surgery (new arthroscopy, controlled dislocation, PAO or conversion to total hip prosthesis [THP]) and calculating the date of surgery.

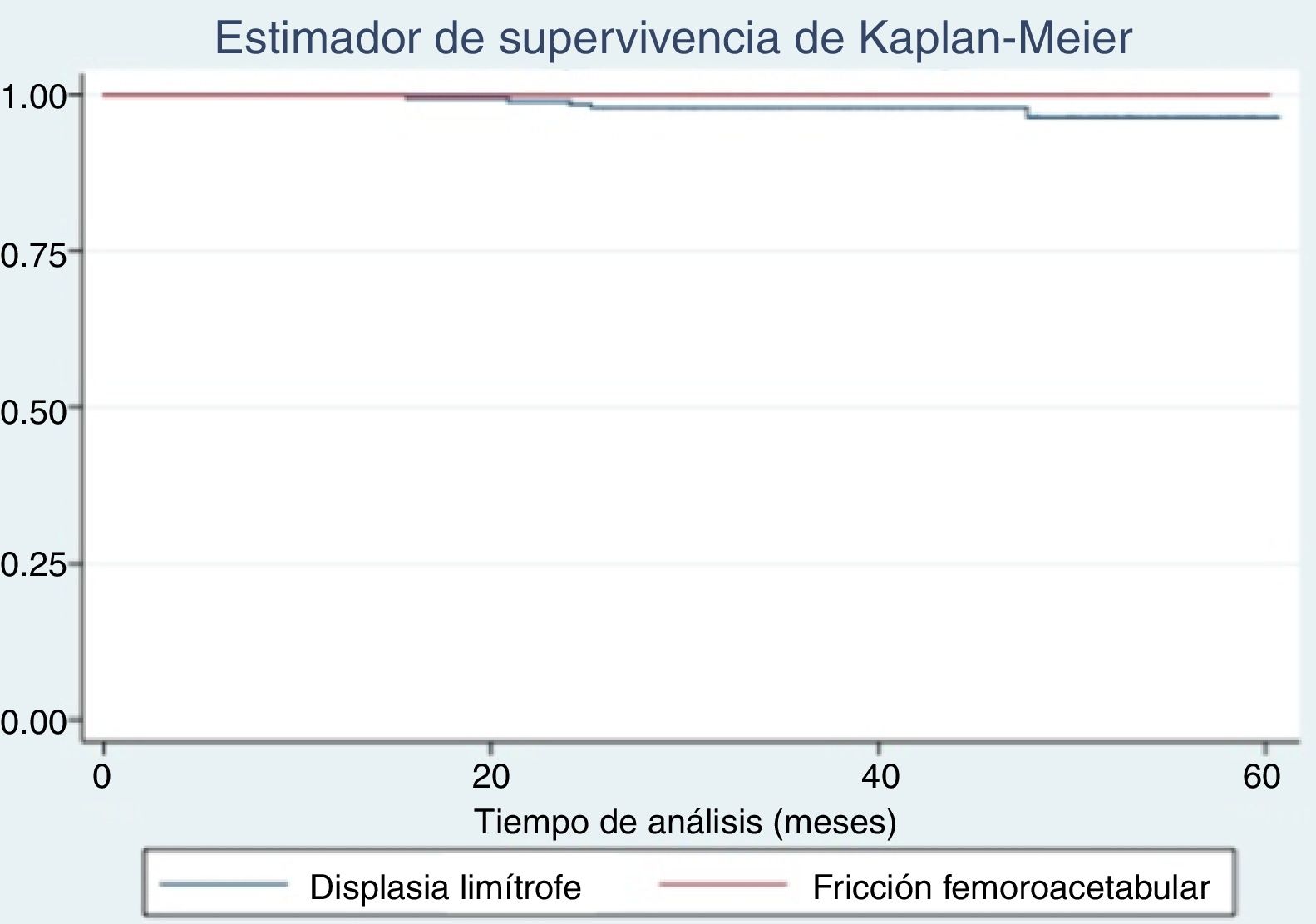

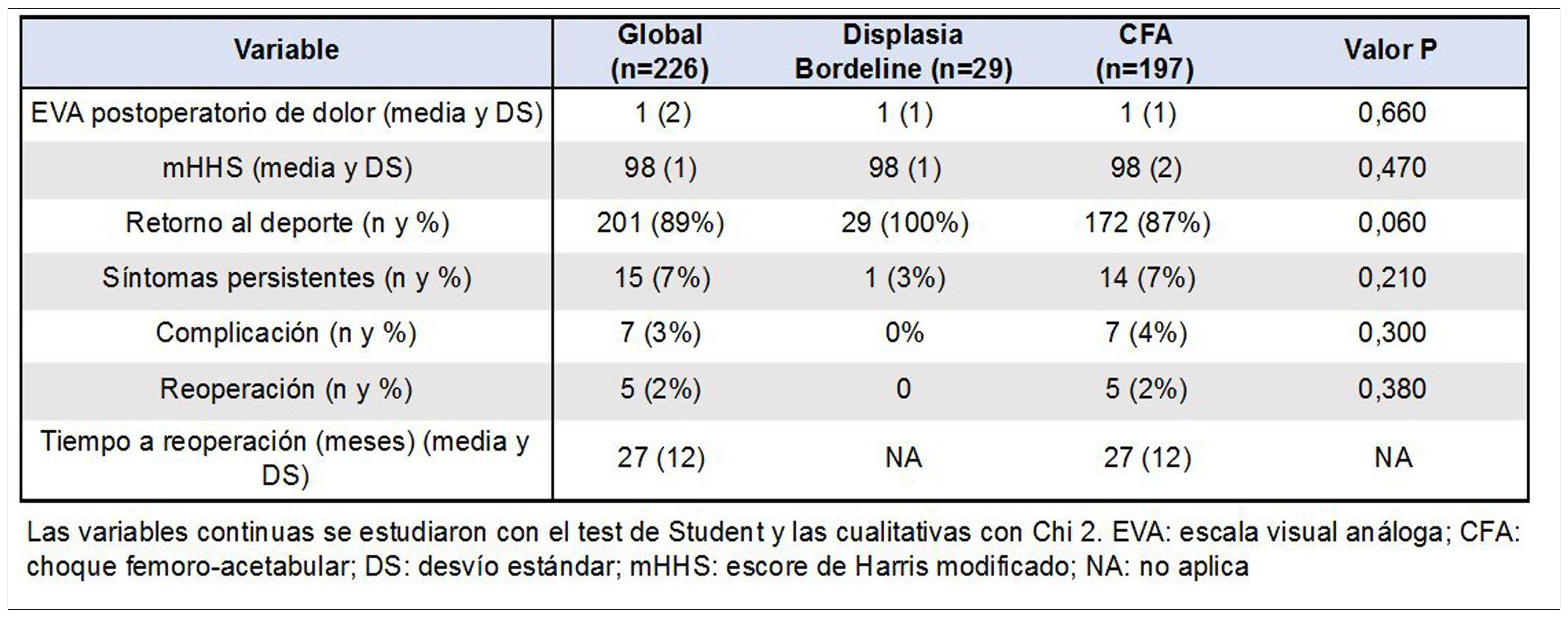

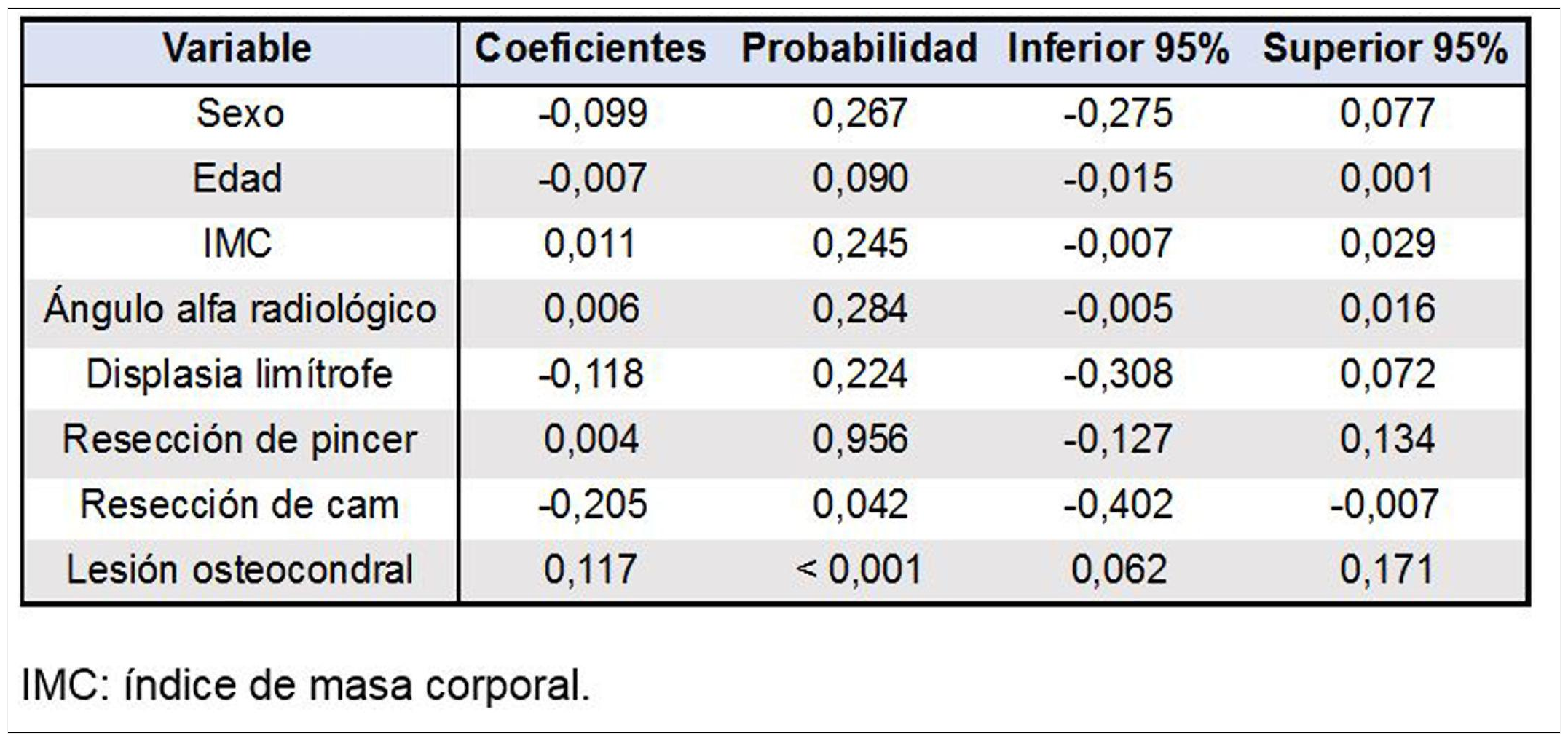

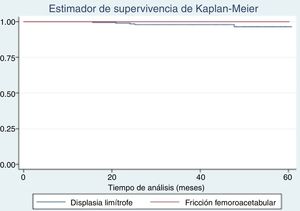

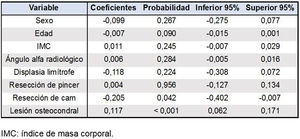

SPSS Statistics® (version 20; IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. The demographic statistics were evaluated as mean and range or standard deviation. The chi-square test was used for the comparison of categorical variables and the Student’s t-test for continuous variables, establishing a significance level at p<.05. The demographic variables and radiological findings of both patient groups were compared to analyse the evolution of clinical outcomes. A linear multivariate regression analysis was performed to evaluate reoperations according to age, sex, BMI, radiological alpha angle, borderline dysplasia, pincer and cam resection, as well as the presence of osteochondral lesions in the arthroscopy. An analysis of joint survival according to the dates of joint failure and the last control was carried out with the Kaplan-Meier method. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare and received no financial support to perform this study.

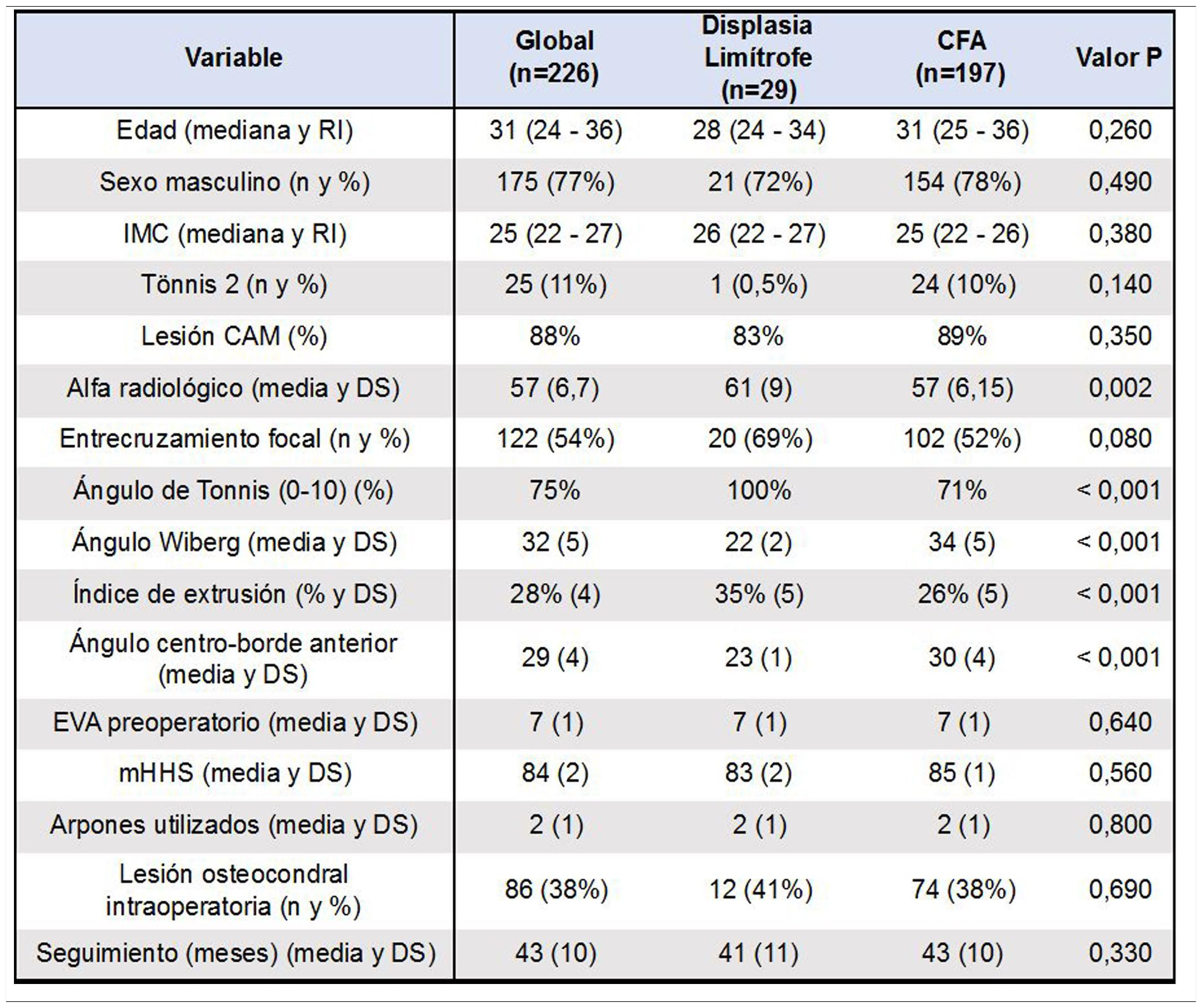

ResultsNone of the cases in the dysplasia group had any complications or adverse effects. Seven complications were recorded among the patients in the FAI group: one superficial wound infection requiring antibiotic medical treatment for 15 days; 3 pudendal nerve paraesthesias that resolved spontaneously in all cases towards 3 months postoperatively; one deep vein thrombosis and 2 cases of heterotopic calcifications in patients who remained asymptomatic.

Thirty-eight percent of the series presented osteochondral lesions during arthroscopy (p=.69). Of these, 42% were treated by microperforations (p=.21) because they were classified as Outerbridge grade 4 during surgery. Five patients in group 2 required further surgery. In 2 of them, reoperation consisted of controlled dislocation due to the progression in the size of their osteochondral lesions at 21 and 48 months from the initial procedure. Both cases presented an Outerbridge 4 osteochondral lesion greater than .5cm2 in the initial arthroscopy, which was treated by microfractures. The 3 remaining cases were treated with revision arthroscopy due to the persistence of their symptoms at the 22 months postoperatively, as it was considered that the osteochondroplasty was insufficient in the first procedure. However, the joint preservation rate was 100% since by the end of the follow-up none of the patients had to be converted to THP. Although there were no reoperations in the borderline dysplasia group, this difference with the FAI group was not statistically significant (p=.38) (Fig. 2).

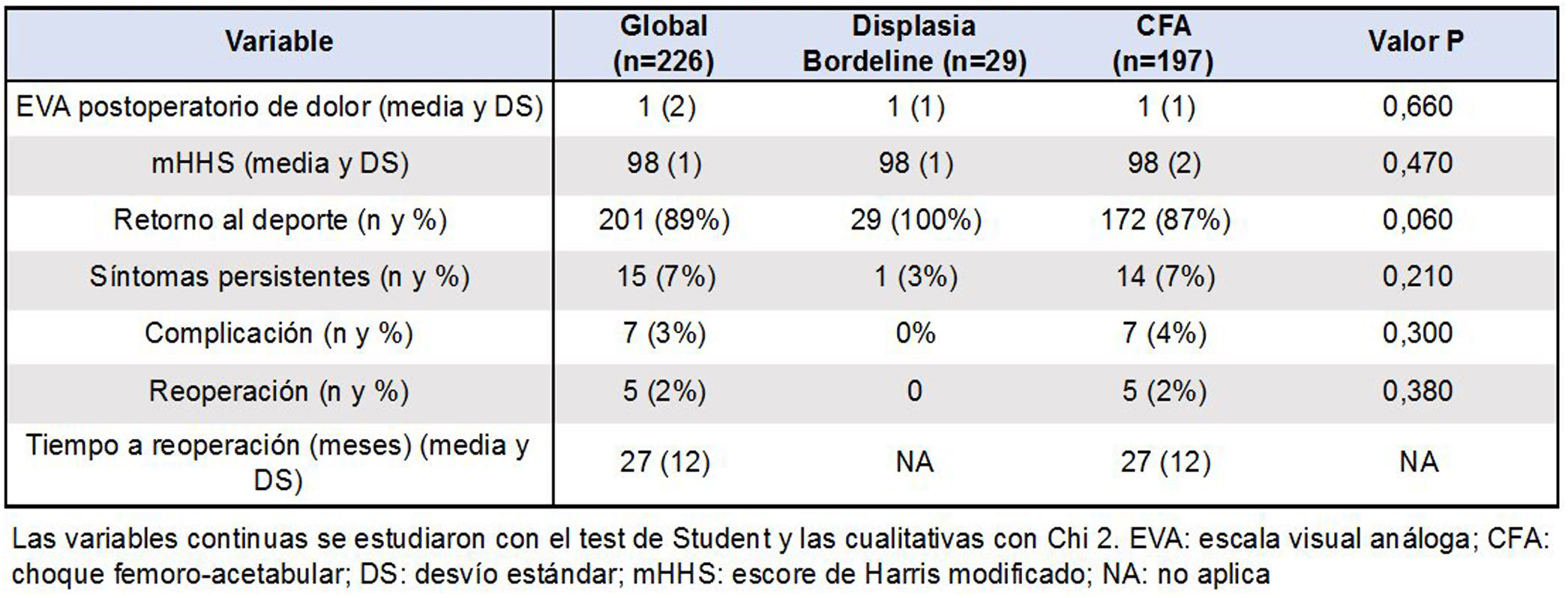

The improvement in pain towards the end of the follow-up for the 2 groups was significant with a postoperative VAS of 1 in both (p=.66); 7% of the patients with FAI and 3% of those with borderline dysplasia (p=.21) showed some symptom during the postoperative period, which was reported in most cases as discomfort during sport that did not require analgesic treatment. The average preoperative mHHS was 83 points in the borderline dysplasia group and 85 in the FAI group (p=.56), improving towards the end of postoperative follow-up to 98 points in both groups (p=.47) (Table 2).

The multivariate regression model adjusted for reoperation showed a very strong statistical association between the finding of osteochondral lesions and therapeutic failure, with a coefficient of .12 (p<.001, 95% CI=.06−.17). Similarly, although the association was weak (p=.04, 95% CI=−.4 to −.01), resecting the cam lesion behaved protectively for the model with a coefficient of −.2 (Table 3).

DiscussionThe present study showed that after treatment with hip arthroscopy, both the patients with borderline dysplasia and those with FAI experienced similar clinical outcomes at a minimum follow-up of 2 years. Furthermore, the failure and reoperation rates were similar in both groups, being higher in cases with osteochondral lesions found in the arthroscopy, regardless of initial diagnosis.

However, our study had certain limitations. Firstly, the number of patients included is small, which means that the statistical analyses could present a beta-type error. In addition, the retrospective nature of the design implied inherent and unavoidable biases in the design. Secondly, the radiological measurements did not consider the anterior and posterior acetabular coverage index.17 The new classification of dysplasia considers that the coverage defect may not only be lateral (overall), but that there may also be an exclusive anterior wall or posterior wall deficiency in the presence of normal lateral coverage.27 Likewise, there was no standardised analysis of tomographic 3D reconstruction28 and all the radiological measurements were taken on radiographs taken in the supine position, presenting a risk of faulty interpretation due to the lack of axial load with possible lack of adjustment due to pelvic tilt.29 Thirdly, we consider that the average follow-up of the series is short term and therefore our results of joint survival should be considered a low estimate. Finally, the preoperative diagnosis of the symptoms of instability or femoroacetabular friction was made according to the subjective assessment of the surgeon in charge, without their being evaluated through clinical scores from physical examination already validated in the literature. This would imply an inherent diagnostic interpretation bias, since some cases of borderline dysplasia with undetected concomitant cam could have been mistaken for clinical instability, or vice versa.21,30,31

The gold standard for the treatment of hip dysplasia consists of a reorientation pelvic osteotomy, especially for cases of severe dysplasia (with a lateral centre- edge angle of less than 18°) and with radiological Shenton line break.32 PAO is generally used in these cases to restore normal acetabular coverage and normalise axial load distribution, although this procedure carries the risk of numerous potential complications, even for experienced surgeons.33,34 In cases of borderline dysplasia, however, the indication for PAO is not entirely clear since instability is often not the cause of pain.35

In the available literature, the terms "borderline dysplasia" or "subtle dysplasia" may lead to errors of interpretation. Wilkin et al. and Nepple et al. suggested avoiding this term by detecting real defect of containment of acetabular bone by means of x--ray and tomographic 3D reconstruction.27,28 In fact, McClincy et al. have already described that hips categorised as borderline dysplasia with lateral coverage of 18° to 25° have other radiological abnormalities compatible with dysplasia36 This also implies that several hips with "borderline dysplasia" could have characteristics of both dysplasia and FAI.37 Thus, it is essential to perform a thorough physical examination to distinguish between symptoms of instability and friction. Indeed, analysis of the lumbopelvic complex is also of great importance, since lumbar lordosis can influence pelvic tilt and indirectly impact hip range of motion.38

Previous studies have found an association between certain spine-pelvic parameters, such as greater standing pelvic tilt or lower pelvic incidence, with symptomatic FAI.39 Other reports have shown that a decrease in pelvic tilt on anteroposterior x-rays, standing rather than supine, would result in a decrease in the incidence and magnitude of cross-over sign and sciatic spine sign, thus increasing the acetabular tilt.32 These authors propose that radiographic study with the patient standing should be routine evaluation in patients with non-degenerative joint pain in the hip, especially for pincer-type lesion.40,41 Our protocol for the study of painful hip in young patients included an anteroposterior radiographic incidence of pelvis and Dunn's profile without load, considering that radiological control at the time of surgery is also performed in the supine position.

Likewise, a pelvic reorientation osteotomy could exacerbate FAI and worsen clinical outcomes due to the presence of a cam FAI.42,43 Whether due to overcorrection or an underdiagnosed cam, contact between the femur and acetabulum may worsen after an PAO.42 As previously suggested, comprehensive clinical evaluation to rule out symptoms of instability is of critical importance in indicating arthroscopic treatment in these cases and should be interpreted in conjunction with radiographic analysis of Wiberg angle, Tönnis angle and anterior and posterior wall coverage. In this respect, it is not surprising that in our series the Tönnis angle did not reach values above 10° in any case as this would increase the symptoms of instability. On the other hand, the finding of a cam- type lesion was very frequent in both groups (83% in the dysplasia group and 89% in the FAI group); and strikingly, the alpha angle was significantly higher in the cases of borderline dysplasia. This would justify the initial indication for hip arthroscopy for all patients in the described series. Although cam can often go unnoticed, it is always necessary to evaluate decrease in head-neck "offset" as a cause of undetected FAI.44

Initial results of hip arthroscopy in the treatment of dysplasia have been less than encouragin;45 there have even been reports of worsening instability symptoms due to iatrogeny.46 However, good to excellent short-term clinical and radiological results have been reported with this treatment in several case series over time. Byrd and Jones described significant improvement in mHHS in 32 patients with borderline dysplasia treated with arthroscopy at an average follow-up of 27 months, without finding therapeutic failure.47 Fukui et al. reported the results of 100 patients with borderline dysplasia who were treated with arthroscopy by capsular plication in all cases and correction of cam in 93%.48 At 3.3 years of follow-up, the authors found 7% arthroscopic review and 5% conversion to THP. More recently, Nawabi et al. conducted a retrospective analysis of 46 cases of borderline dysplasia with 131 age- and sex-matched controls with normal LCEA treated with hip arthroscopy.16 They found no significant difference in the reoperation rate: 4.3% of the dysplasia group and 4.6% of the control group required revision arthroscopy. Similarly, Cvetanovich et al. compared 36 patients with borderline dysplasia with 312 cases of FAI treated with arthroscopy, finding no clinical difference or requirement for a new surgical procedure (3% in the dysplasia group vs. 1.6% in the control group).49 Our findings, although short term, seem to be in line with what has been reported, considering that we have described 0% reoperations in the borderline dysplasia group and 2% in the FAI group.

We found a strong association between arthroscopic finding of osteochondral lesion and surgical failure with need for reoperation. Of the 5 failures in the FAI group, 2 presented an Outerbridge 4 osteochondral lesion (treated with controlled dislocation) and a grade 2 (treated with arthroscopy).22 Bogunovic et al. prospectively studied 1724 consecutive hip arthroscopies, of which 60 failed and required either revision arthroscopy (n=38) or conversion to THP (n=22).50 The authors concluded that inadvertent residual deformities (cam and pincer), advanced osteoarthritis and grade 4 osteochondral lesions were associated with therapeutic failure. Hatakeyama et al. performed a case-control study to evaluate the predictors of failure after hip arthroscopy for the treatment of dysplasia, finding the following markers of reoperation: age greater than 42 years, radiological Shenton line break, Tönnis angle greater than or equal to 15°, osteoarthritis greater than or equal to Tönnis grade 1, severe delamination in the acetabular cartilage and moderate chondral damage in the femoral head.51 While mild to moderate acetabular cartilage damage appears to be well tolerated, severe damage is not.52 These reports, like our results, highlight the importance of preoperative assessment as to the condition of the articular cartilage in highly sensitive and specific imaging studies in order to identify the best candidates with borderline dysplasia who could benefit from arthroscopy.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, arthroscopic treatment of labral hip lesions in patients with FAI and borderline dysplasia did not yield significant differences in survival, complications, or functional outcomes at a mean follow-up of 43 months. Although short term, these results appear to be in line with previous publications evaluating similar demographic cohorts. Therefore, we believe that hip arthroscopy is useful in the treatment of borderline dysplasia, but we suggest that it be carefully indicated and only selected for specific patients in whom the symptom of femoroacetabular friction is greater than that of instability. This usually results in the radiographic finding of associated cam signs on the femoral side.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III, cases and controls, prognostic study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Slullitel PA, Oñativia JI, García-Mansilla A, Díaz-Dilernia F, Buttaro MA, Zanotti G et al. ¿Es útil la artroscopia de cadera para el tratamiento de la displasia limítrofe?: análisis de casos y controles. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recot.2020.04.006