We present a case report of an occipital condyle fracture, a rarely seen injury in patients of any age, and particularly so in paediatric patients. The objective of this article is to inform about this lesion, such often going unnoticed, but should be especially looked for in cranial trauma cases with neck pain. An X-ray may be normal and diagnosis is best made by using computed tomography imaging. Treatment should depend on whether the fracture is stable or not.

Material and methodsWe report on two patients, 17 and 40-year-old males who presented with an impacted right occipital condyle fracture following a motorbike accident. Cervical immobilization was carried out with a hard collar.

ResultsGood results were obtained and there were no secondary effects of a neurological or functional nature.

Conclusion and clinical relevanceIn conclusion, the knowledge of this condition, its correct diagnosis and the correct treatment choice are crucial to the avoidance of brachial plexus injuries and other important sequelae.

Llamar la atención sobre la existencia de la fractura del cóndilo occipital y la facilidad con la que pasan desapercibidas durante la atención del paciente politraumatizado. Es una lesión poco frecuente, especialmente en pacientes adolescentes, y debe tenerse en cuenta ante un traumatismo craneal con dolor cervical por sus potenciales consecuencias si estas fracturas no se tratan correctamente. La exploración radiográfica puede parecer normal, debiendo hacer el diagnóstico mediante tomografía computarizada. El tratamiento de elección depende de la estabilidad de la fractura.

Material y métodoDos pacientes varones de 17 y 40 años involucrados en sendos accidentes de motocicleta, presentaron una fractura impactada del cóndilo occipital. En ambos casos se realizó tratamiento conservador con collar cervical rígido.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron buenos resultados funcionales sin secuelas neurológicas.

Conclusión y relevancia clínicaEl conocimiento y sospecha de esta infrecuente entidad y su correcto diagnóstico y tratamiento es crucial para conseguir un buen resultado funcional, para así evitar potenciales lesiones neurológicas asociadas.

Occipital condyle fracture (OCF) is rare—particularly in children and adolescents. Because the diagnosis is frequently missed on simple X-rays, it is recommended that computerized tomography (CT) be used.1 Understanding, early diagnosis, and proper clinical management of this injury may prevent possible neurological damage, such as cranial nerve paralysis and medullary compression.2

In patients with an OCF, the associated injuries are varied and often non-specific3—from no neurological involvement at all to atlanto-occipital dissociation (AOD) with loss of consciousness. Bloom et al.4 described a series of 4 paediatric patients with this fracture who had no alarming neurological signs.

We present 2 cases exemplifying an impacted occipital condyle fracture diagnosed on CT scan and treated conservatively with good results.

Clinical casesPatient 1The patient was a 17-year-old male who had been involved in a motorcycle accident. At the scene of the accident, Emergency Services personnel removed the integral helmet he was wearing and put him into a Philadelphia collar. Patient presented with multiple traumas, the foremost being a head injury. Upon arrival in the Emergency Room, his Glasgow score was 13, with temporal disorientation and incoherent speech; his pupils were equal and reacting normally, osteotendinous reflexes were present and symmetrical, and there was no evidence of central neurological injury.

He had an open fracture of the right forearm and a fractured left clavicle. The neurological examination revealed loss of movement in the right arm as well as in the first and second fingers of the left hand.

The cervical region was immobilized with a rigid collar, and the patient was started on a corticosteroid regimen for suspicion of a brachial plexus injury secondary to elongation.

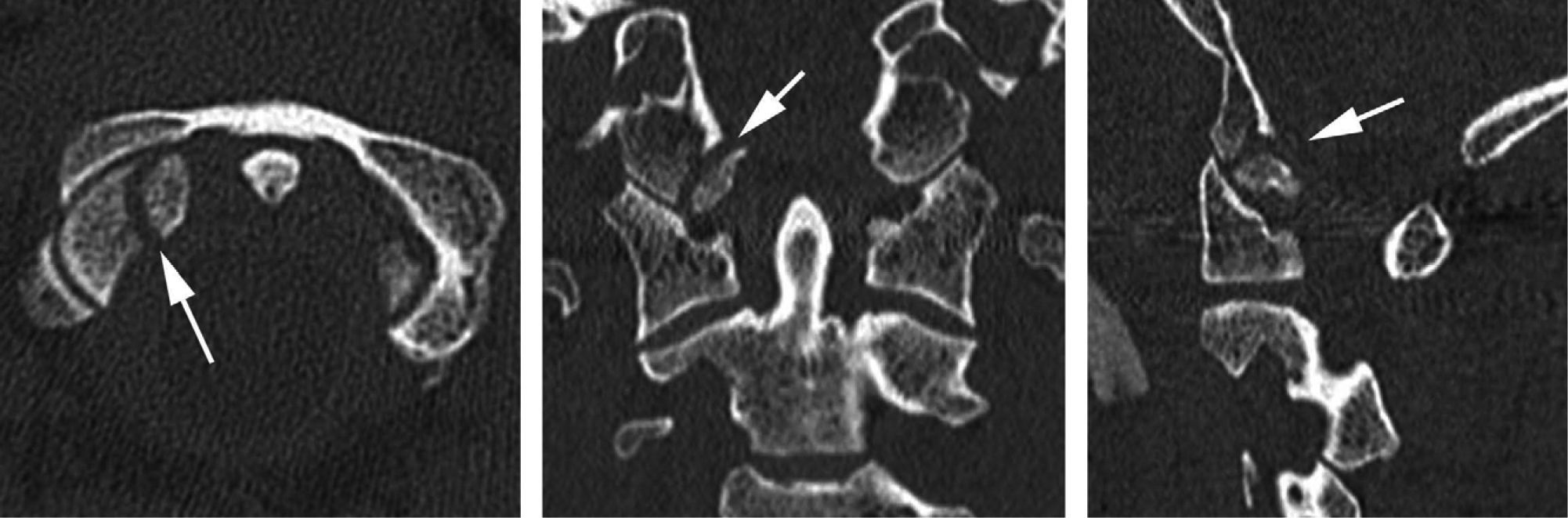

X-ray findings included right ulnar and bifocal radial fractures as well as a three-fragment fracture of the left clavicle. The patient's pelvis was stable despite bilateral ischiopubic ramus fractures and a 2-cm diastasis symphysis pubis. Cervical X-rays in anteroposterior and lateral views showed no injuries. CT scan of the head and neck (Fig. 1) revealed an impacted fracture (type I) of the right occipital condyle and a C1 fracture. Proper diagnosis was assisted by 3D reconstructions. Cervical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed no ligament rupture, so the fracture was considered stable. The image of one of the neural foramina was consistent with pseudomeningocele.

The patient was transferred to the paediatric intensive care unit (ICU), where an electromyogram showed a postganglionic brachial plexus injury.

Patient 2This patient was a 40-year-old male with multiple injuries from a motorcycle accident in which he was not wearing a helmet. Upon arrival in the Emergency Room, his Glasgow score was 12, so the decision was made to sedate and intubate him. Swelling over the left clavicle was found on the initial examination.

X-rays and CT scan (Fig. 2) were done, showing a fracture in the middle third of the left clavicle, fracture of the right occipital condyle (type I), right external Schatzker I tibial plateau fracture, contusion of the right lung, and fracture of right costal arches 1, 2, 3, and 6.

Patient was admitted to ICU for monitoring. His neck was immobilized with a rigid collar to treat the occipital condyle fracture. The clavicle was treated conservatively and, at 7 days, the patient underwent knee surgery.

During outpatient follow-up, the patient showed full functional recovery of the neck with no sequelae.

Because, in both cases, there was no atlanto-occipital dislocation (AOD) and the fractures were considered stable, according to current classifications and recommendations,5 the treatment of choice was conservative treatment using a rigid cervical collar for 2 months, and proper fracture healing with full range of motion was achieved.

Discussion and literature reviewThese clinical cases serve as a reminder that, for diagnosing an occipital condyle fracture—first described in 1817 by Sir Charles Bell6—it is very important to have a high index of suspicion because this is an unusual injury that is difficult to diagnose without a CT scan or MRI.

A peak incidence at 20–40 years of age has been found due to traffic accidents. In most cases, clinical findings are limited to diffuse neck pain, but paresis of the lower cranial nerves (IX–XII) sometimes occurs, the hypoglossal nerve being the most commonly affected. The proximity of the occipital condyles to the hypoglossal canal and jugular foramen explains why displacement of a condyle fracture could compromise or cut off the surrounding cranial nerves. Another possibility is brainstem ischaemia due to compression of the vertebral artery, with the resulting neurological impairment. In a case reported recently, there were internal carotid artery lesions7; in another case, retropharyngeal haematomas were found.8

The most serious cases are those in which the occipital condyle fracture is associated with AOD, for this may result in death due to injury of the medulla oblongata.

There are not many references on OCF in the literature; in our review of the literature, we found about 30 paediatric cases9 and some 150 adult cases. While the exact incidence of this injury is unknown,10 some articles report a 4–18% incidence in patients with severe head injury and low level on the Glasgow scale.11 Wider use of CT scans and MRI has led to increased diagnosis of these injuries. However, most of these articles describe a small patient series. A retrospective study by Hanson et al.12 showed that simple X-rays are of limited use in evaluating this injury and that a CT scan is required to arrive at a correct diagnosis.

There are 3 traditional classifications for OCF. The first, proposed in 1987 by Satermus,13 is based on cadaver studies and has little practical worth. One year later, Anderson and Montesano14 described a series of 6 patients, 2 of whom were under 21 years of age. They differentiated between 3 types of fracture with and without associated ligament injury. Type I is considered stable because the membrana tectoria and the contralateral alar ligament are intact. The mechanism of injury is axial compression. Type II is a basal skull fracture extending to the occipital condyles and not associated with craniocervical ligament injury; it is considered stable, unless the fracture line completely separates the condyles. This fracture results from a direct blow to the head. Type III is potentially unstable owing to ipsilateral avulsion of the occipital condyle and, therefore, carries the risk of the bone fragment being displaced within the foramen magnum toward the odontoid process. Lateral inclination with rotation is the cause of this type of occipital condyle fracture.

In 1997, Tuli et al.11 presented a new classification based on instability of the occiput-C1–C2 complex, displacement of the condyle, and ligament rupture. Type I is described as a non-displaced fracture and is considered stable. A type II fracture is displaced but has no evidence of ligament injury on MRI; it is also considered stable. Type III consists of a displaced occipital condyle fracture with MRI showing instability of the occiput-C1–C2 complex and rupture of craniocervical ligaments; it is considered unstable.

A fourth classification was recently presented,5 which adds a prognostic factor and classifies the OCF according to whether it is unilateral or bilateral and whether it is or is not associated with AOD. Type I is a unilateral fracture without AOD; it is a stable fracture that has a good prognosis and should be treated with a cervical collar. Type II is a bilateral fracture without AOD; although it has higher comorbidity, it is a stable fracture that is also treated with a rigid cervical collar. Type III fractures are those with associated AOD; they are considered unstable, have a poor prognosis with a high rate of mortality and complications, and must be treated surgically.

Most authors agree that the Anderson and Montesano classification is the most practical, which is why it was the one we used for our study. According to this classification, type I and II fractures should be treated with a rigid cervical collar, while unstable type II fractures and type III fractures should be treated with a cervical halo or similar device. In our review, we found only 1 adult patient who required surgery to stabilize this injury. A study by Momjian et al.9 showed that, with proper treatment, these fractures tend to heal without sequelae.

If neurological involvement is suspected, an emergency CT scan should be done because simple X-rays may appear to be normal, and the underlying occipital condyle injury could be missed. On the lateral view, the condyles are superimposed on the mastoid process and the mandible. Tuli et al.11 identified this fracture by X-ray in only 2 of the 51 cases they studied. With current technology, the test of choice is 3D reconstruction of the CT scan—a technique that is useful for determining the number of fragments4—while MRI is reserved for evaluating adjacent structures for injury.

In summary, occipital condyle fracture is difficult to diagnose and may be missed, if it is not suspected. Although routine X-rays usually appear to be normal, sometimes there is a slight soft tissue displacement that points us toward the correct diagnosis. A CT scan is required in patients who have suffered a head injury and are complaining of pain in the neck—even if they have no apparent neurological injury—because, as Demish15 and Orbay16 have shown, neurological deficits may not appear until 2–3 months after the accident.

Proper diagnosis and treatment of this injury are crucial in preventing possible neurological injuries later on. With the use of a rigid cervical collar, there is full neurological and functional recovery from a stable OCF.

Evidence levelEvidence level V.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of Data. The authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Please cite this article as: Abat F, et al. Fractura del cóndilo occipital. Reporte clínico y revisión de la literatura. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol 2012;56(1):67-71.