The purpose of this study is to present a method for treating the serious consequences that result from failure of corrective techniques used for hallux valgus, which produces severe shortening of the first ray, and makes it difficult to perform the third rocker.

Material and methodsIn this study, conducted in 2 hospitals in Madrid and Barcelona, an assessment was made of the clinical and radiological results of 40 cases, of which 97.5% were female.

Technically it involves making a metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis after bone distraction with an external mini-fixation, and then inserting an iliac crest bone graft, stabilising it with a plate or the mini-fixator.

ResultsThe pre-operative shortening was 2.5cm and elongation obtained was between 1.5 and 3.0cm. Clinical and radiological bone graft integration was achieved at 2–4 months, although full integration occurred after one year.

Falliner and Blauth criteria were used to evaluate the results at 6 and 12 months follow-up, and using Visual Analogue Scale (VAS score/pain, scale 1–10), being favourable in 80%, and not changing over time.

The failure rate was 7.5%, which included the non-integration of the graft and infection, requiring additional surgery.

DiscussionThere are not many publications on the number and type of complication for hallux valgus surgery, or guidelines established, only the treatment by conventional fusion.

The problem arises when the patient presents a severe shortening of the ray, and direct fusion would aggravate the insufficiency of the first ray and the transference metatarsalgia. In these cases, these procedures would be indicated.

Se expone un procedimiento para tratar las secuelas originadas por fracaso de técnicas correctoras del hallux valgus, que producen grave acortamiento del primer radio con metatarsalgia severa y dificultad para realizar el tercer rocker.

Material y métodosEl trabajo, realizado en 2 hospitales de Madrid y Barcelona, analiza los resultados clínicos y radiológicos de 40 casos, en los que predomina el sexo femenino en un 97,5%.

Técnicamente consiste en realizar una artrodesis metatarsofalángica, previa distracción ósea con un minifijador externo, y posteriormente interponer un injerto óseo de cresta ilíaca, estabilizándolo con una placa o con el mismo minifijador.

ResultadosEl acortamiento medio preoperatoriamente fue de 2,5cm y el alargamiento obtenido osciló entre 1,5 y 3,0cm. La integración ósea clínica y radiológica se consiguió a los 2–4 meses, manteniéndose esta al año de seguimiento.

Para valorar los resultados, se aplicaron los criterios de Blauth y Falliner en periodos intermedios y al año de la cirugía, mediante la Escala Visual Analógica (VAS score/dolor, escala 1-10) que fueron favorables en un 80%, sin modificarse en el tiempo.

La tasa de fracasos fue del 7,5%; cabe destacar la no integración del injerto y la infección, que requirieron cirugía adicional.

DiscusiónHay escasas publicaciones sobre graves secuelas de la cirugía del hallux valgus, tampoco hay pautas establecidas al respecto, salvo la artrodesis convencional.

El problema se plantea cuando el paciente presenta grave acortamiento con metatarsalgia severa y una artrodesis metatarsofalángica directa que agravaría el problema al acortar más el primer radio. En dichos casos nuestros procedimientos están indicados.

The failure of the anterointernal support of the foot presents as a complication in some techniques to correct hallux valgus.1,2 This leads to a biomechanical alteration of the forefoot caused by excessive shortening of the first ray and a dysfunctional metatarsophalangeal joint. This causes imbalance in the load forces acting on the heads of the central metatarsal bones, leading to transfer metatarsalgia.

These sequellae are often very complex to treat, so that it is hard to decide which treatment is the most appropriate for each case. A poor surgical indication or unsuitable treatment would cause new complications3,4 and more severe sequellae.

The most frequent causes are surgical techniques that excessively resect the base of the proximal phalange, such as the Keller–Brandes procedure, although we now more commonly see failures of diaphyseal or distal metaphyseal osteotomies of the first metatarsal bone of the “chevron” type, caused by technical errors or injury to the vessels that supply the head, leading to ischaemic necrosis.5,6

Other less common causes are postsurgical osteomyelitis, the inappropriate resection of the head of the metatarsal bone (the Hueter–Mayo technique) and those procedures which when they fail lead to a reduction in the length of the first ray,6 as occurs with failure of a total metatarsophalangeal prosthesis that has to be removed (Fig. 1).

There are several therapeutic objectives: to normalise the length of the first ray and toe pattern, establishing anterointernal support, regulating the transmission of loads to prevent stress fractures in the central metatarsal bones (Fig. 1) and eliminating the metatarsalgia, as well as permitting normal walking and improving the appearance of the forefoot, making it possible to use ordinary footwear.

The surgical procedure we propose is to perform, following elongation with an external minifixator, metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis, interposing an autogenous structural bone graft with subsequent internal or external fixation to keep the graft compressed between the two adjacent bone structures5 in a suitable position (10–15° of extension and 5–10° valgus).

Before making decisions a series of factors relating to the morphology of the area must be taken into consideration, because in all of these sequellae anterointernal support is modified due to the shortening of the phalange or metatarsal bone by an average of 2 or 3cm.

Sometimes a subluxation or luxation of the first metatarsophalangeal joint coexists with a backward movement of the sesamoid bone (Fig. 1). The smaller toes are also dorsally luxated, usually with involvement of the plantar plate which aggravates the metatarsalgia.

In all cases clinical and imaging examination must be performed with great care, to permit a precise diagnosis and an exact evaluation of the morphology of the whole forefoot.7

Problem in the proximal phalangeThis is the most frequent problem. The proximal phalange measures is less than 2.5–3cm long on average (insufficient phalange), it does not make contact with the ground and is sometimes unstable (“floating toe”) and it does not act in liftoff. In this case a direct arthrodesis would aggravate the symptoms, as the first ray would be shortened.

Problem in the metatarsal boneThe mechanical conditions in the metatarsal bone are aggravated by the backward movement of the sesamoid bones and insufficient support during the second and third “rocker”. In cases with osteomyelitis the shortening is greater, due to the obligatory resection of the bone in surgery, down to healthy tissue.

Sometimes the defect is caused by an injury to both structures, in the metatarsus as well as in the proximal phalange, making it necessary to perform a larger bone resection. If the metatarsal bone is very short and the real space is greater than 3cm, we should then consider modifying the central metatarsal bones (shortening osteotomy) to normalise Maestro's metatarsal pattern. A graft longer than 3cm in these cases may lead to problems with integration.

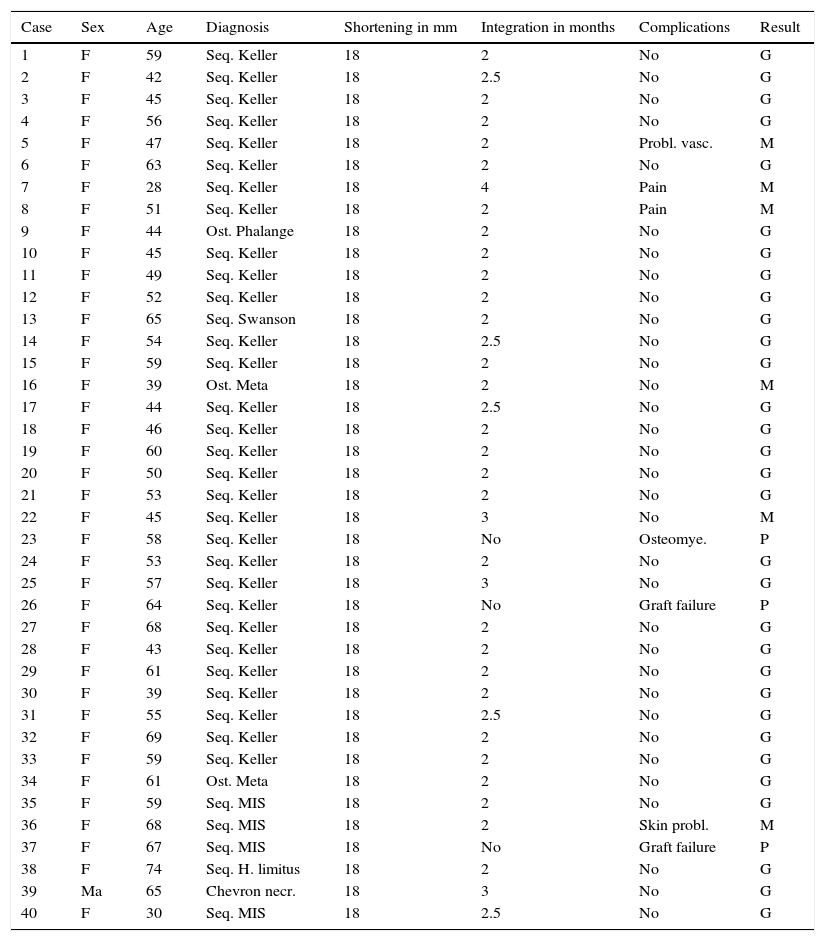

Material and methodsThis series includes 40 patients treated in 2 hospitals, in Madrid and Barcelona, from 1999 to 2013 (Table 1): 14 cases correspond to the first series published, which was used as the basis for this work. Of the whole series in general, 39 patients were female (97.5%) and one was male (2.5%). Their ages ranged from 28 to 68 years old, with the majority of cases (72.5%) grouped in the fourth to sixth decades.

List of patients operated.

| Case | Sex | Age | Diagnosis | Shortening in mm | Integration in months | Complications | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 59 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 2 | F | 42 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2.5 | No | G |

| 3 | F | 45 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 4 | F | 56 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 5 | F | 47 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | Probl. vasc. | M |

| 6 | F | 63 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 7 | F | 28 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 4 | Pain | M |

| 8 | F | 51 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | Pain | M |

| 9 | F | 44 | Ost. Phalange | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 10 | F | 45 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 11 | F | 49 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 12 | F | 52 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 13 | F | 65 | Seq. Swanson | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 14 | F | 54 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2.5 | No | G |

| 15 | F | 59 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 16 | F | 39 | Ost. Meta | 18 | 2 | No | M |

| 17 | F | 44 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2.5 | No | G |

| 18 | F | 46 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 19 | F | 60 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 20 | F | 50 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 21 | F | 53 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 22 | F | 45 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 3 | No | M |

| 23 | F | 58 | Seq. Keller | 18 | No | Osteomye. | P |

| 24 | F | 53 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 25 | F | 57 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 3 | No | G |

| 26 | F | 64 | Seq. Keller | 18 | No | Graft failure | P |

| 27 | F | 68 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 28 | F | 43 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 29 | F | 61 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 30 | F | 39 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 31 | F | 55 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2.5 | No | G |

| 32 | F | 69 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 33 | F | 59 | Seq. Keller | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 34 | F | 61 | Ost. Meta | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 35 | F | 59 | Seq. MIS | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 36 | F | 68 | Seq. MIS | 18 | 2 | Skin probl. | M |

| 37 | F | 67 | Seq. MIS | 18 | No | Graft failure | P |

| 38 | F | 74 | Seq. H. limitus | 18 | 2 | No | G |

| 39 | Ma | 65 | Chevron necr. | 18 | 3 | No | G |

| 40 | F | 30 | Seq. MIS | 18 | 2.5 | No | G |

Evaluation using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS score/pain. Scale 1–10).

Good: no pain, complete fusion and elongation. Normalisation of the shape of the toe, normal shoes, satisfied patients: 33 cases (82.5%).

Mediocre: occasional pain, complete fusion. Requires orthopaedic devices and special footwear, difficulty in walking: 4 cases (10%).

Poor: constant pain, failed fusion, pseudoarthrosis, dissatisfied patient. Repeat surgery is an option: 3 cases (7.5%).

G: good; F: female; P: poor; Meta: metatarsal bone; MIS: minimal incision surgery; Necr.: necrosis; Ost.: osteotomy; Osteomye.: osteomyelitis; Probl.: Problems; M: mediocre; Seq.: sequellae; Ma: male; vasc.: vascular.

They all presented severe sequellae with first ray insufficiency secondary to surgical correction of hallux valgus. These were caused by several different surgical procedures:

- •

Sequellae of resection arthroplasty (Keller–Brandes) (70%).

- •

Failure of replacement arthroplasty (Swanson prosthesis) (2.5%).

- •

Avascular cephalic necrosis due to chevron osteotomy (12.5%).

- •

Severe shortening due to minimum incision surgical techniques (10%).

- •

Sequellae of hallux valgus limitus (2.5%).

- •

Sequellae of first metatarsal osteotomy (2.5%).

The clinical evaluation of the blood supply to the foot, support while walking and of the hyperkeratosis plantar revealed that the main cause of the problem was the absence of anterointernal support, which led to first ray insufficiency and overloading of the central rays.

Dorsoplantar and lateral and lateral X-rays were taken in all cases of both feet under load. This made it possible to measure the length of the remaining proximal phalange and the metatarsal bone, as well as the existing space, although the definitive measurement had to be made in the operation itself.

An axial projection was useful to see the alignment of the heads of the metatarsal bones and to determine the location of the sesamoid bones.

Magnetic resonance imaging with coronal projection was indicated in some cases to better evaluate the frontal alignment of the metatarsal bone and the existence of bursitis or Morton's neuritis.

A bone scintigraphy scan was sometimes used with technetium 99 or gallium 67 to rule out osteonecrosis or an infection in the metatarsal bone or phalange.

The study of some cases was completed with electromyography to evaluate the existence of a plantar nerve lesion caused by an earlier surgical procedure.

Different types of minifixators able to elongate or compress were used for prior elongation. In 15% of the cases a low profile shaped plate with 7 or 9 holes was implanted, while in the remaining 85% an external minifixator with 4 pins was used. A 6 hole plate was used in one case with delayed consolidation.

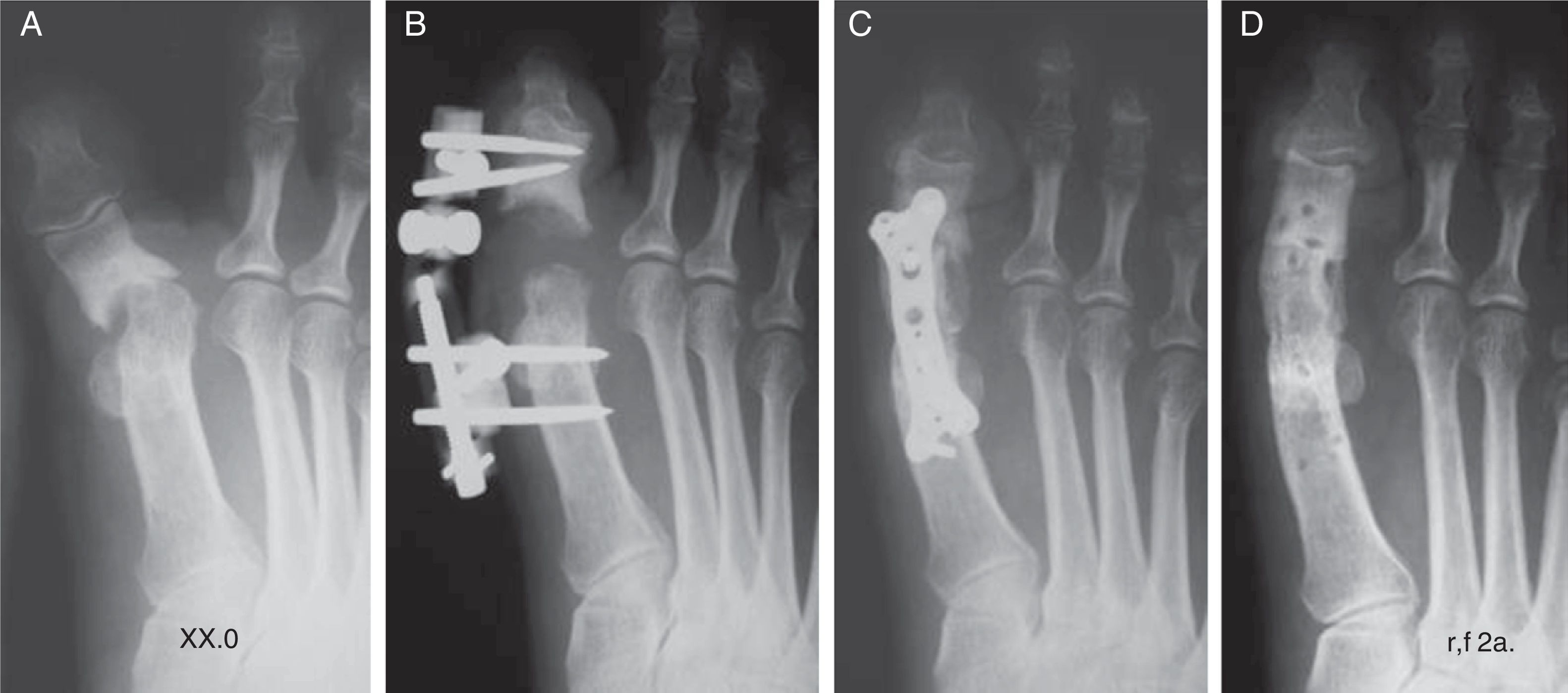

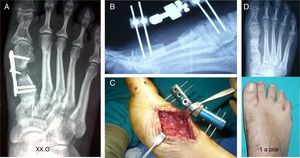

Specific surgical techniqueA two-stage procedureThis makes it possible to elongate gradually and in a controlled way to recover space. This is indicated for patients who may have the vascular risk of ischaemia in the big toe (Fig. 2).

(A) Sequellae due to failure of the Keller–Brandes technique. (B) Gradual elongation with an external minifixator in a first stage. (C) Graft for interposition and internal fixing with a low profile plate in a second stage. (D) Removal of the implant after 2 years. Appearance of the graft.

The dorsal and medial skin must be in good condition, and previous scars must have healed.

The focus is accessed surgically to permit the appropriate debridement of fibrous and fibrocartilaginous tissue. Both bone surfaces are prepared until healthy vascularised bone is visible.

Both bones are then stabilised using an external minifixator. Two threaded pins are inserted into the diaphysis of the metatarsal bone; 2 others are positioned in the proximal phalange and, if the latter is estimated to be too short, they may be positioned in the distal phalange. Elongation commences.

The second stageGradual elongation takes place at 2–3mm per day, followed by verification that the toe is vascularised.

Once the desired elongation has been achieved after 10–15 days another surgical procedure is performed. The fixator is removed and the same incision is used to resect any remaining fibrous tissue, and the bone graft obtained from the iliac crest and previously measured is implanted between the two bone surfaces.

Immediately afterwards the whole assembly is stabilised using a suitably-sized low profile shaped plate, implanted in the dorsum from the proximal phalange to the metatarsal bone, thereby ensuring that the graft is held between both structures. It is necessary to compress the graft with the plate, to aid the integration of the graft. A “bed” must be prepared using spongy bone from the crest itself to aid contact between the graft and the two bone ends.

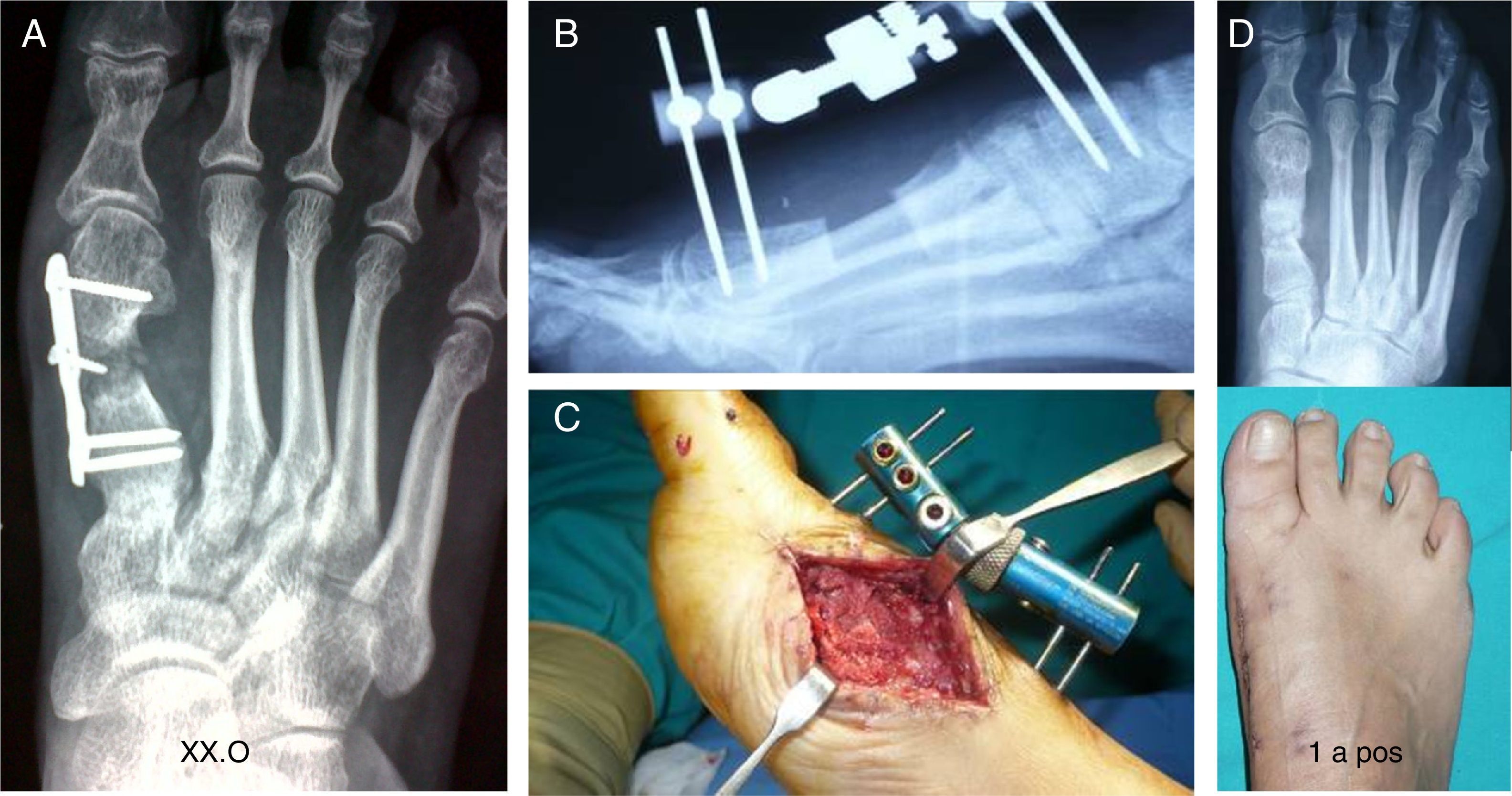

Three stage procedureThis is indicated in those cases where the phalange is severely shortened and greater elongation is required, of approximately 3cm. These are severe lesions, the sequellae of several previous operations, and sometimes the skin is in poor condition. These patients habitually present propulsive metatarsalgia (third rocker) due to a short first metatarsal bone and a big toe that does not make contact with the ground (a floating toe). These cases may present ischaemia of the toe is elongation proceeds swiftly (Fig. 3).

(A) Clinical and radiological appearance of severe sequellae of the Keller–Brandes technique. 3 stage procedure. (B) Gradual elongation with the minifixator, graft for interposition, clinical and radiological appearance at 2.5 months. (C) Clinical and radiological result after one year.

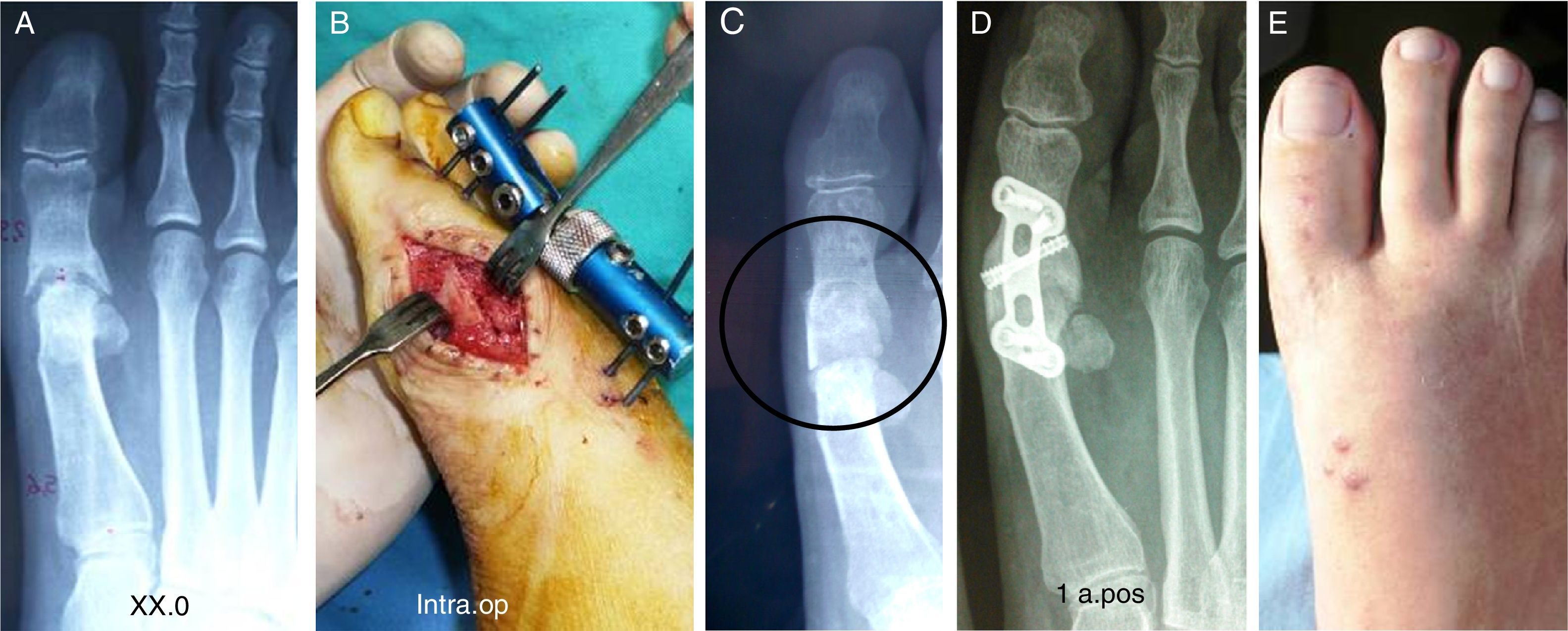

This procedure is mainly indicated in cases of severe shortening of the first metatarsal bone due to the sequellae of failed corrective osteotomies (Fig. 4) and it must be a priority in cases of osteoarthritis, infection or avascular necrosis of the head, which it may be necessary to resect; also in cases of the failure of a metatarsophalangeal prosthesis which has to be removed.

This takes place in the same way and with the same characteristics as the first stage described above.

The second stageProlongation using the minifixator must also be gradual (2–3mm per day) until the desired length is reached in 7–19 days. During this time the vascular state of the toe must be evaluated every day. Finally, the clinical length achieved must be checked by X-ray.

If the soft tissues are in good condition a new surgical operation is performed to implant the bone graft between the two bones as in the preceding procedure and it is stabilised using compression in this case, with the same external minifixator.

The third stageUnlike the first procedure, in which compression was applied using the plate in the same surgical operation, in this case compression will be applied gradually and daily by the external fixator until it reaches maximum compression.

The graft and fixator must be checked regularly until the bone is radiologically integrated, which generally occurs after 2 or 3 months.8 Cure of the pins must be exhaustive, to prevent them from loosening.

After the fixator is removed the stability and integration of the graft must be confirmed clinically and radiologically.

The chief advantage of this second procedure is that after removing the fixator no osteosynthesis material is left in contact with the bone (Fig. 5) Although the plates may remain, in some cases it is necessary to remove them after one year, above all if there is local discomfort. In these cases the graft must be checked to ensure that it has not changed and keeps its whole structure (Fig. 2).

Sequellae of minimally invasive surgery (M.I.S.). (A) Arthrosis of the proximal phalange and necrosis of the metatarsal bone head, resection down to healthy bone leads to shortening by 3cm. (B) Elongation and the interposed bone graft. (C) No graft integration at 4 months. (D) Osteosynthesis due to delayed consolidation. (E) X-ray image showing complete consolidation at one year. Clinical result.

During 6–8 weeks after the operation gradual assisted loading with crutches was indicated for all of the patients, with a dorsally fenestrated plaster boot. After this a walker-type orthesis attached to the fixator was used until week twelve.

Once the integration of the graft had been confirmed, the walker was removed and the use of habitual soft footwear was permitted.

The decision to apply the procedure n 2 or 3 stages will depend on the individual needs of each patient and the characteristics of each particular case: the cause of the sequellae, the size of the phalange, the number of previous operations, skin condition, previous scars, bone quality and the state of big toe vascularisation.

ResultsPostoperative clinical and imaging checks were performed at regular intervals in all cases during the first year and in subsequent follow-up checks.

The average shortening of the phalange prior to the operation was 2.5cm.

The prolongation obtained varied in a range from 1.5cm to 3cm, with an average of 2.5cm. The clinical and radiological integration of the graft was confirmed on average after 2–4 months, and it remained after a follow-up of one year. No significant clinical or radiological difference was observed depending on the procedure used.

The preoperative intermetatarsal angle ranged from ranged from 12° to 16° in all of the cases. Given the nature of the procedure other angles such as the metatarsophalangeal angle and the distal joint angle of the metatarsal bone were not taken into account.

In 90% of the cases the smaller toes were affected (claw and hammer toes, etc.), which also had to be treated in the same operation. In one case cement had to be extracted from where it had been used as a spacer before the implantation of the bone.

The original criteria of Blauth and Falliner published in 19979 were used to evaluate the results of this series. We used the same methodology in our first series, published in 1999.10 This has allowed us to compare all of the results published by the said authors. This is why the AOFAS evaluation was not used.

Although intermediate evaluations were performed, those undertaken 12 months after surgery were used as the reference (Table 1).

All of the cases were followed-up during 1–3 years: the good results did not change over time and the patients remained satisfied with the clinical and functional results obtained.

The failure rate was 7.5%. The most serious complications were failure of the graft to integrate when the fixator was removed (Fig. 5) and one graft infection; both cases required additional operations. In the first case, with an osteosynthesis that evolved satisfactorily, and resection of the graft in the second case, which meant going back to the previous situation and following subsequent treatment with orthesis. Another patient needed a Goldfarb-type elevation osteotomy in the base of the central metatarsal bones to treat residual metatarsalgia.

Complications due to problems in the soft tissues (wounds and lesions caused by the pins in the skin) were slight: second try scarring with a gradual cure was sufficient.

Four cases, corresponding to 10% of the series, were not satisfied due to the persistence of metatarsalgia, so that an unloading orthesis was required so that they could live their usual life.

With a few slight differences the results described above are practically identical to those obtained by Blauth and Falliner in their original work.

DiscussionMetatarsophalangeal arthrodesis is a procedure of choice for the surgical correction of severe hallux valgus with major instability of the metatarsophalangeal joint, especially in cases accompanied by arthrotic degenerative processes or rheumatoid arthritis. It is also useful and offers good results for reconstruction of the first ray, due to the sequellae of the failure of different surgical techniques used to correct hallux valgus, as described by different publications on this subject.11–13

The main problem arises in cases where there is excessive shortening of the phalange or the metatarsal bone or both, due to previous surgery or defective technique. In these cases a direct arthrodesis aggravates the biomechanical and clinical problem as it resects the bone surfaces down to healthy tissue, leading to greater shortening of the first ray.

To prevent this circumstance it is necessary to interpose a cortical-spongy graft of the right size between the 2 bone ends, to recover the lost length and the functional capacity of the first ray. Normalisation of the length gives rise to a stable first ray that is able to withstand the load and prevent transfer metatarsalgia due to overloading of the central rays.14–16

In their original work in 1997 Blauth and Falliner developed this procedure in a single stage, stabilising the graft with 2 intramedular Kirschner needles that were removed after 8 weeks, and which did not make the assembly stable.

Internal fixing with low profile plates or external fixing are more stable options that make it possible to keep the graft compressed. This aids its integration and prevents vascular problems as the elongation is gradual.

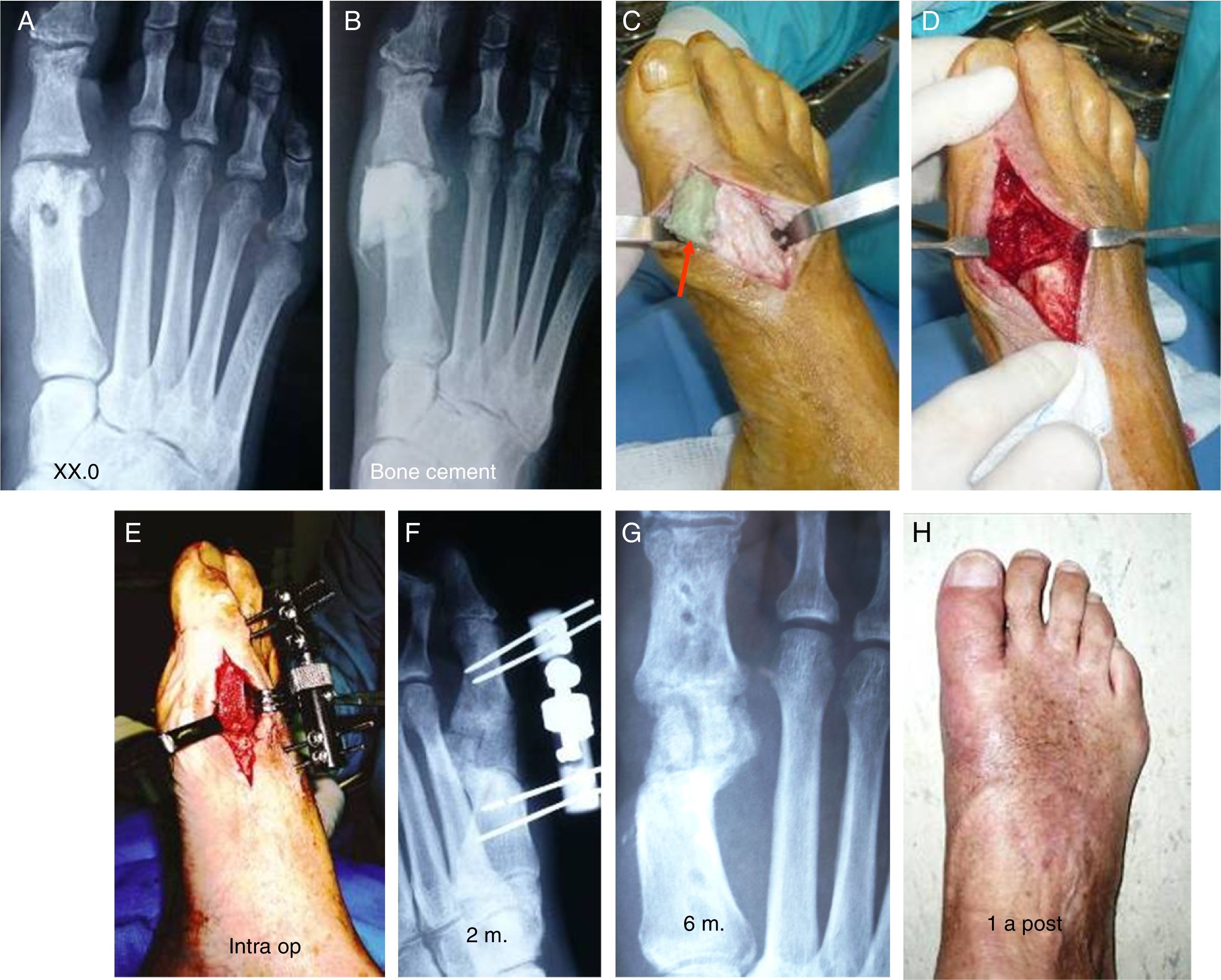

Myerson17 recommends the use of a small external fixator, especially in cases with infection (Fig. 6), and which also require the resection of the affected bone to ensure cure and the subsequent implant of the interposed structural graft that will restore the length of the ray.

(A) Infectious arthritis after a chevron osteotomy. (B) Resection of the necrotic metatarsal head bone and implantation of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) as a temporary spacer. (C) Extraction of the cement. (D) Preparation of a zone for the graft. (E) Elongation with an external minifixator. Implantation of the structural bone graft. (F) X-ray of the minifixator and bone graft at 3 months. (G) Radiography at 6 months. (H) Clinical result at one year.

Malhotra18 recently published the same system but without previous elongation, solely with manual elongation and in a single stage. The series consists of 25ft operated on over 10 years, with graft stabilisation by Kirschner needles and low profile plates. Only 3 failures that required a repeat operation are mentioned. Luk and Johnson19 also reported good results in 2015 using the same technique in 15ft, although they used bone allografts that self-stabilised by means of bipolar reaming and without osteosynthesis. Results were favourable in 87% of cases, with graft integration in 21 weeks and 3 failures.

By using the technique of arthrodesis by elongation and the interposition of an autogenous cortical-spongy bone graft, the length of the first ray that had been lost can be recovered, so that the feeling of a “floating toe” disappears; the phalangeal and metatarsal bone patterns improve and anterior support is normalised. The associated transfer metatarsalgia also disappears in 80% of cases, and patients express a high level of satisfaction, together with a clinical and aesthetic improvement: their problems with using footwear disappear.

Both methods of stabilisation, in 2 stages (plate) or in 3 (permanent external fixator) have the same aim. They only differ in their methods, so that their clinical and radiological results are identical, as was observed.

The indication to use one method or the other will depend on the natural history of the sequellae, infection, previous surgery and the characteristics of the deformity, etc.

Although both procedures are for bone stabilisation, the external fixator requires greater care and attention than the plate after the operation as well as during removal. We therefore consider this to be a third stage within the procedure.

The positive response of the patients, with absence of pain at 6 months, leads us to consider that arthrosis by means of elongation and the interposition of bone is a good technique for these serious complications of hallux valgus surgery, which often represent a serious problem for the surgeon preparing to treat them.

We believe that the options we present in this work will make it possible to select the most suitable approach for each particular case.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that the procedures followed conform to the ethical norms of the responsible human experimentation committee and the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the paper. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

To María Luisa Ampudia (Virgen del Mar Hospital, Madrid) and Raquel Rodríguez Vidal (Tres Torres Clinic, Barcelona), operating theatre instrument technicians, for their help in the surgery of these patients.

Please cite this article as: Núñez-Samper M, Viladot R, Ponce SJ, Lao E, Souki F. Secuelas graves de la cirugía del hallux valgus: opciones quirúrgicas para su tratamiento. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:234–242.