Metastatic bone disease is the most common neoplastic process that affects the skeletal system. Eighty percent of bone metastases come from carcinomas of the breast, lung, kidney, thyroid and prostate. The Katagiri scale enables an estimation of the survival of patients based on the presence or absence of visceral metastases, multiple bone metastases and functional status according to the ECOG scale.

Material and methodsA retrospective, descriptive and observational study conducted between March 1, 2013 and June 30, 2015. Thirty-two patients were studied with a diagnosis of metastatic bone disease and who had undergone some type of orthopaedic surgical treatment for pathological fracture or impending fracture.

Results28 cases (87.5%) presented pathological fracture and 4 cases (12.5%) impending fracture according to the Mirels score. Fifteen cases (46.875%) were treated by placing a central medullary nail+spacer in the long bone diaphysis, 15 cases (46.875%) with modular arthroplasties and 2 patients (6.25%) with forequarter amputation. Eleven patients (34.375%) died during the course of this study, all with a Katagiri greater than or equal to 4.

DiscussionThe presence of a fracture in previously damaged territory is a catastrophic complication for most cancer patients. A clear understanding of the life expectancy of patients with bone metastases is of great help to prevent errors and failures in treatment.

La enfermedad ósea metastásica es el proceso neoplásico más común que afecta al sistema esquelético. El 80% de las metástasis óseas están dadas por los carcinomas de mama, pulmón, riñón, tiroides y próstata. La escala de Katagiri permite hacer una estimación de la supervivencia de los pacientes con base en la presencia o ausencia de metástasis viscerales, múltiples metástasis óseas y el estado funcional.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo, descriptivo y observacional realizado entre el 1 de marzo del 2013 y el 30 de junio del 2015 en donde se estudió a 32 pacientes con diagnóstico de enfermedad ósea metastásica a los que se les realizó algún tipo de tratamiento quirúrgico ortopédico por fractura patológica o inminencia de fractura.

ResultadosVeintiocho casos (87,5%) presentaron fractura patológica y 4 casos (12,5%) con inminencia de fractura de acuerdo con el score de Mirel; 15 casos (46,875%) fueron tratados mediante colocación de clavo centromedular + espaciador diafisario en huesos largos, 15 casos (46,875%) con artroplastias modulares y 2 pacientes (6,25%) desarticulación glenohumeral. Once pacientes (34,375%) fallecieron durante el transcurso de este estudio, todos ellos con un Katagiri igual o mayor de 4.

DiscusiónLa presencia de una fractura patológica es una complicación catastrófica para la mayoría de los pacientes con cáncer. Un claro entendimiento de la expectativa de vida de los pacientes con metástasis óseas es de gran ayuda para prevenir errores y fallas en el tratamiento.

The life expectancy of oncological patients has increased due to progress in chemotherapy and radiotherapy, improvements in surgical techniques and the development of new cancer treatments. Due to this the incidence of bone metastasis has also increased.1–3

Bone is the third most common site for metastatic disease, after the lungs and liver.1,2,4 Metastatic disease in the bone is the most common neoplastic process that affects the skeleton.5 Eighty per cent of bone metastases arise due to carcinomas of the breast, lungs, kidney, thyroid and prostate.5

Metastatic destruction reduces the load-bearing capacity of bone, initially causing trabecular disruption, microfractures and then the loss of bone continuity.2

The most frequent symptom is pain, which may be incapacitating, localised or diffuse, and it may or may not be associated with the presence of a fracture in a previously damaged area.3 Metastatic bone disease is considered to be the greatest contributor to deterioration of the quality of life of patients with cancer.1,2,4

Of the different forms of treatment, non-surgical methods are usually insufficient as they reduce patient quality of life and are associated with a higher probability of fracture non-consolidation.2,6 The surgical treatment of bone metastases is palliative, and it aims to achieve local control of the disease and structural stability, restoring function as quickly as possible.2

There are scales which allow us to take decisions on the best options for management. Katagiri's scale7 is one of these, and it makes it possible to estimate patient survival as well as to suggest surgical treatment based on the presence or absence of visceral metastasis, multiple bone metastasis and functional state according to the ECOG8 scale. Mirels developed a scoring system to predict the risk of fracture in long bones with metastatic disease, so that prophylactic supports could be prepared.9 We analyse the functional state of patients after surgery according to the Musculoskeletal Tumour Society scale (MSTS).10

The aim of this work is to describe the experience in the surgical treatment of bone metastasis in the appendicular skeleton, in the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Mexico.

Material and methodsA retrospective, descriptive and observational study was performed during the period from 1 March 2013 to 30 June 2015. It included 32 patients with the diagnosis of metastatic bone disease who were treated with some type of orthopaedic surgery due to pathological fracture or an imminent fracture.8 All of them were evaluated prior to surgery using Katagiri's scale,7 with a follow-up of at least 6 months after surgery. Patient quality of life was evaluated suing the ECOG scale, and their postoperative functional state was evaluated using the MSTS.

Statistical analysis was recorded in a database prior to analysis using version 19.0 of the SPSS for Windows (IBM SPSS Software version 19.0 for Windows, Chicago, IL 60606, USA). Descriptive statistics were produced, with records of averages, standard deviations and a frequencies table. The chi-squared test was used to analyse factors associated with complications, and the odds ratio was used to quantify risk factors. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to evaluate survival, while the Mantel–Cox log rank test was used to compare survival curves. p<.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance, with a 95% confidence interval.

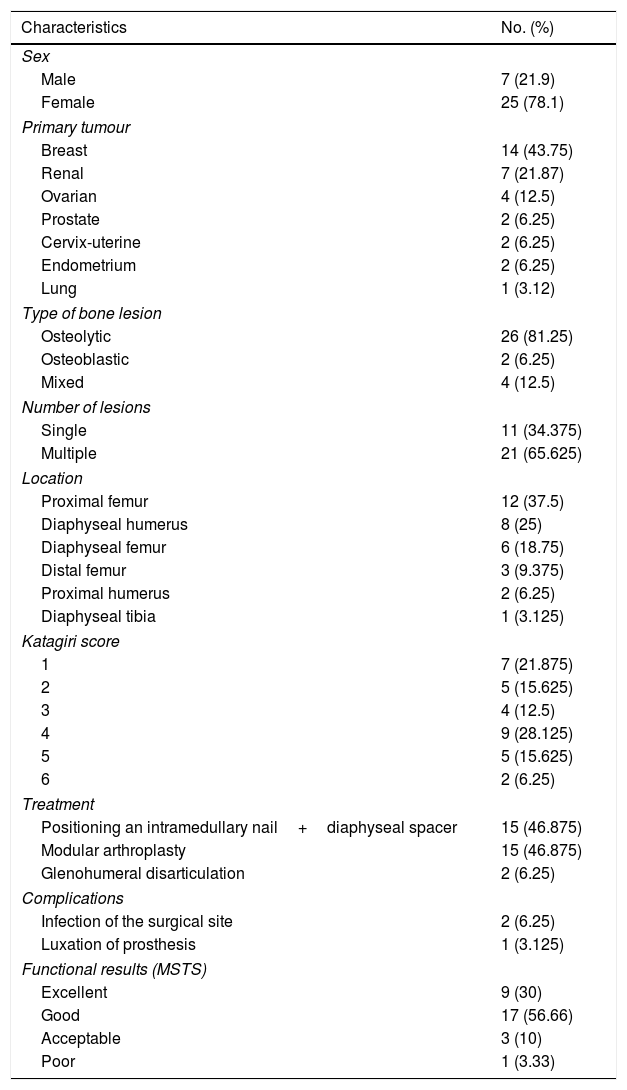

ResultsOf the 32 cases analysed, 25 patients (78.125%) were female and 7 were male (21.875%). Their average age was 63.09 years old (35–91 years old).

Breast cancer was the most frequent primary tumour, in 14 cases (43.75%), followed by 7 cases of kidney cancer renal (21.87%), 4 cases of ovarian cancer (12.5%), 2 of prostate cancer (6.25%), 2 uterine cervix cases (6.25%), 2 endometrial cancers (6.25%) and one lung cancer (3.125%).

Both patients included in the study with the diagnosis of prostate cancer (6.25%) had osteoblastic lesions, while 4 patients (12.5%) with breast cancer had mixed bone lesions, and the others (26 patients, 81.25%) had lytic bone lesions.

Twenty one patients (65.625%) had multiple skeletal lesions, while 11 (34.375%) had single skeletal lesions. As well as these 32 patients who were analysed, 11 (34.375%) were associated with visceral metastasis, all of them lung metastases.

The main site of bone metastasis in the appendicular skeleton was the proximal femur, with 12 cases (37.5%), followed by the diaphyseal humerus with 8 cases (25%), the femoral diaphysis in 6 cases (18.75%), the distal femur in 3 cases (9.375%), the proximal humerus in 2 cases (6.25%) and the tibial diaphysis in one case (3.125%).

The distribution of the orthopaedic diagnosis was as follows: 28 cases (87.5%) had a pathological fracture and 4 cases (12.5%) had an imminent fracture according to the Mirels score.8 The cases were distributed as follows according to their location: 12 patients had fracture of the proximal femur (37.5%), while there were 8 diaphyseal humerus fractures (25%), 4 case with the risk of imminent fracture of the diaphyseal humerus (12.5%), 3 fractures of the distal femur (9.375%), 2 fractures of the diaphyseal femur (6.25%), 2 fractures of the proximal humerus (6.25%) and one fracture of the diaphyseal tibia (3.125%).

The decision on patient treatment was made by specialists in different fields, taking into account the prognostic factors which form Katagiri's score. The minimum score was 1 point and the maximum score was 6 points, with an average of 3.09.

The surgical procedures performed were distributed as follows: 15 cases (46.875%) were treated by positioning an intramedullary nail+a diaphyseal spacer with polymethyl methacrylate in the diaphysis of long bones, 15 cases (46.875%) with modular arthroplasties and 2 patients (6.25%), one diagnosed breast cancer and the other with endometrial cancer, were subjected to glenohumeral disarticulation due to the extension of the tumour with damage to the neurovascular bundle and lack of skin coverage (Table 1).

Results of patients with metastatic bone disease.

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 7 (21.9) |

| Female | 25 (78.1) |

| Primary tumour | |

| Breast | 14 (43.75) |

| Renal | 7 (21.87) |

| Ovarian | 4 (12.5) |

| Prostate | 2 (6.25) |

| Cervix-uterine | 2 (6.25) |

| Endometrium | 2 (6.25) |

| Lung | 1 (3.12) |

| Type of bone lesion | |

| Osteolytic | 26 (81.25) |

| Osteoblastic | 2 (6.25) |

| Mixed | 4 (12.5) |

| Number of lesions | |

| Single | 11 (34.375) |

| Multiple | 21 (65.625) |

| Location | |

| Proximal femur | 12 (37.5) |

| Diaphyseal humerus | 8 (25) |

| Diaphyseal femur | 6 (18.75) |

| Distal femur | 3 (9.375) |

| Proximal humerus | 2 (6.25) |

| Diaphyseal tibia | 1 (3.125) |

| Katagiri score | |

| 1 | 7 (21.875) |

| 2 | 5 (15.625) |

| 3 | 4 (12.5) |

| 4 | 9 (28.125) |

| 5 | 5 (15.625) |

| 6 | 2 (6.25) |

| Treatment | |

| Positioning an intramedullary nail+diaphyseal spacer | 15 (46.875) |

| Modular arthroplasty | 15 (46.875) |

| Glenohumeral disarticulation | 2 (6.25) |

| Complications | |

| Infection of the surgical site | 2 (6.25) |

| Luxation of prosthesis | 1 (3.125) |

| Functional results (MSTS) | |

| Excellent | 9 (30) |

| Good | 17 (56.66) |

| Acceptable | 3 (10) |

| Poor | 1 (3.33) |

Of the 15 modular prostheses used, 12 (37.5%) were bipolar modular hip prostheses and 3 were modular knee prostheses (9.375%); 15 intramedullary nails were used, of which 8 (25%) where in the diaphyseal humerus, 6 were in the diaphyseal femur (18.75%) and one was in the tibia (3.125%).

Three patients (9.375%) had postoperative complications. 2 of them (6.25%) had superficial infection of the surgical wound which was managed conservatively using antibiotics, while one patient had luxation of the hip prosthesis (3.125%). The latter was treated by open reduction and the positioning of a constrained acetabular component.

The functional results were evaluated in the consultation prior to surgery and at 2 weeks after surgery. Using the functional MSTS as the reference, the functioning of the operated limb was evaluated in 30 of the 32 patients subjected to rescue surgery of the limb, while the ECOG scale was used to evaluate the overall clinical state of all our patients. On the MSTS, 9 patients (28.125%) had excellent results, while for 17 they were good (53.125%), for 3 they were acceptable (9.375%) and for one they were poor (3.125%). The last case was the patient with luxation of the prosthesis, and after the second surgical procedure (to reposition the acetabular component) the functional result was good. We found a maximum functional percentage of 93%, a minimum value of 26%, a median of 83% and an average of 79.56%.

The clinical state of the patients was evaluated using the ECOG scale8 before and after surgery. In the multivariate analysis the functional state of all of the patients was found to have improved after surgery (p=.028).

Eleven patients (34.375%) died during the course of this study. The average survival time of our patients was 22.87 months after the surgical procedure, in a range of 6–34 months.

DiscussionThe presence of a fracture in a previously damaged area is a catastrophic complication for the majority of cancer patients.11 A clear understanding of the life expectancy of patients with bone metastasis greatly aids the prevention of errors and failures in treatment. Several reports in the literature state that only patients with an expected survival time of at least 6 months would benefit if a surgical procedure is considered.2,7,8 Therefore, the patients with the greatest life expectancy will benefit from a surgical procedure involving a more extensive resection and reconstruction.1,2,8,12

The age range considered in this study is very broad due to the heterogeneous nature of the multiple primary cancers analysed, with a minimum age of 35 years old and a maximum age of 91 years old, with an average of 63 years old. The predominance of female patients, at 78%, is due to the lytic characteristics of the breast, ovarian, uterine, cervix and endometrial cancers included in this study.13

Breast cancer is the main origin of bone metastasis, which may be osteolytic, osteoblastic or mixed.1,2 None of the patients with a diagnosis of breast cancer included in this study had osteoblastic lesions; this may be due to the fact that the lytic behaviour of metastatic lesions leads to a higher risk of complication (fracture or risk of fracture).1,2 This is corroborated by the fact that in our study only 6 patients (2 with osteoblastic lesions and 4 patients with mixed lesions) had a pathological fracture.

Our patients benefited from multidisciplinary analysis and the use of scales such as Katagiri's, as all of the patients who died had a Katagiri score of 4 or higher. Although it seems that there may be an inverse relationship between the Katagiri scale score and survival, this study does not allow us to find it.2,7,14–16 Eleven patients (34.375%) died during the course of this study.

The site most commonly affected by bone metastasis was the proximal femur, with 12 cases (37.5%); this coincides with similar reports in the literature.1,2,17 Due to their extension all of these cases were treated by modular hip arthroplasty. The treatment of choice in diaphyseal lesions is resection of the site of the metastasis and reconstruction by inserting an intramedullary nail and a cement spacer.18 Polymethyl methacrylate is an excellent adjuvant that permits suitable fixation in patients with fractures in a previously damaged area, and it is also an alternative in those lesions which affect the diaphysis of long bones.19–21

Amputation is an option in metastatic bone disease; its indications include the local control of disease that does not respond to conventional treatments, failure of osteosynthesis associated with constant pain, lack of skin coverage and damage to the neurovascular bundle.1,2,22

If lytic lesions in the distal femur extend for more than 50% of the epiphyseal or metaphyseal zone, endoprosthetic replacement is considered to be the treatment of choice.1,2 This procedure was performed on 3 patients (9.37%) due to the extension of the tumour, so that the patients were unable to walk.1,18

Functional results in oncological patients are limited due to the resection that involves disinsertion of the muscles and the resulting limitation to mobility.18,23 Using the musculoskeletal scale we found that good functional results predominated (17 patients, 53.125%) over excellent results (9 patients, 28.125%), acceptable results (3 patients, 9.375%) and one poor result (3.125%). The latter was due to luxation of the prosthesis, and after repositioning its acetabular component the functional result was good. These results coincide with the functional results described in the literature.18,24,24

Functional improvement is explained by the fact that the pain and limitations arising from a pathological fracture or imminent fracture direct affect our patients’ quality of life.

The techniques for the surgical treatment of bone metastases differ considerably from those used to set a fracture caused by trauma. This is because the malign tissue has to be eliminated, while pathological fractures are associated with a delay in bone consolidation.2,18,25 Only 3 patients (9.375%) has postoperative complications, of whom one patient (3.62%) had hip prosthesis luxation that was treated surgically by repositioning the acetabular component. Two patients had superficial infection of the surgical wound. There was no relationship between the type of surgery performed and the type of complication.

ConclusionsThe surgical treatment of metastatic bone disease in the appendicular skeleton must be individualised, depending on the overall state of the patient and their survival.

Katagiri's prognostic survival scale is a useful tool for orthopaedic surgeons when taking decisions in the case of patients with metastatic bone disease.

Bone metastasis treatment is multidisciplinary and involves interaction between different departments to improve the quality of life of our patients.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on human beings or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their centre of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this paper.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Clara-Altamirano MA, Garcia-Ortega DY, Martinez-Said H, Caro-Sánchez CH, Herrera-Gomez A, Cuellar-Hubbe M. Tratamiento quirúrgico de las metástasis óseas en el esqueleto apendicular. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:185–189.