Framed within the Theory of Reasoned Action, the current work aims to further our knowledge of how social commitment is engendered and what volunteers’ determinants are. Findings to emerge from the empirical study conducted amongst a sample of 488 youngsters aged between 16 and 18 evidence that youngsters’ intention to cooperate with non-government organisations is determined directly by the attitudes they display towards these organisations and towards social issues, and by their immediate environment, and indirectly by their beliefs concerning social conflicts. We highlight the twin role played by attitudes towards non-government organisations (NGOs) throughout the whole process as it proves to be the major determinant of commitment, transforming part of the attitude towards problems into an intention to cooperate, making it a core variable and underscoring the power an organisation's image has to attract volunteers.

El presente trabajo, al amparo de la Teoría de la Acción Razonada, quiere ahondar en el conocimiento del modo en que se genera el compromiso social de los adolescentes y de cuáles son los determinantes del voluntariado. Los resultados del estudio empírico realizado con una muestra de 488 jóvenes de entre 16 y 18 años demuestran que la intención de colaboración de los jóvenes con organizaciones no gubernamentales viene determinada directamente por las actitudes que muestran hacia las propias organizaciones y hacia la problemática social en general y por su entorno más cercano e, indirectamente, por las creencias que posean acerca de los conflictos sociales. Destacamos el doble papel que desempeña la actitud hacia las ONG en todo este proceso, ya que es el principal determinante directo del compromiso y canaliza parte del efecto de la actitud ante los problemas hacia la intención de colaborar. Esto la convierte en una variable crucial y pone de manifiesto las posibilidades de las organizaciones de atraer voluntarios a través de su imagen.

A growing awareness of social responsibility has led citizens, occasionally individually although mainly through organisations, to play an increasingly vital role in designing and implementing action aimed at satisfying the general interest and, in particular, eliminating marginalisation and building a caring society able to provide a decent standard of living for all.

Non-government organisations (NGOs) are nonprofit organisations which are not dependent on any government and which pursue the general interest. They are founded on the values of solidarity and social justice. Specifically, Social Action NGOs are citizens’ way of expressing their views by forming groups which seek social, altruistic and caring goals, benefiting those who are underprivileged, excluded and marginalised from society. Their twin objective is to offset the problem of inequality and under-privilege and to promote the structural changes required to ensure these situations do not re-emerge.

Before 1960, social solidarity was very much the domain of religious institutions, families and state welfare policies. Yet, the recession and economic crisis of the 1970s evidenced the limitations of the welfare state and gave rise to the emergence of the so-called Third Sector in developed economies, in the shape of nonprofit and social volunteer organisations (Beerli, Diaz, & Martin, 2004).

In certain countries, the significance of the Third Sector is such that its contribution and size is comparable to other sectors. Over the last three decades in Spain, the Third Sector in general, and the Social Third Sector in particular, has steadily increased in importance and relevance in a social context of growth and expansion (Vidal, 2013). According to data from the 2012 Spanish Social Third Sector Report published by the Luis Vives Foundation, the number of social organisations in Spain stands at around 29,000, who employ 635,961 people and draw on the cooperation of 1,075,000 volunteers. To a large extent, such organisations function thanks to public funding, this representing almost 1.88% of Spain's GDP for the year in question. Yet, because of the financial crisis in 2008, said growth came to a grinding halt. The crisis led to an increase in social needs and to a dramatic cutback in public resources (Vidal, 2013).

There is little doubt that without volunteers devoting their time and effort and without donors contributing funds, NGOs could not survive. Now, more than ever, NGOs must be able to generate social involvement since they are no longer able to count on sufficient public funding to undertake projects without the support of other social groups. They need to know how to encourage people so as to engage them in their mission and to gain people's support by getting them to devote time and money. The key lies in securing and managing said social commitment. Attempts to unearth what drives this have long been a focus of marketing research, and many are the studies which have sought to ascertain what the determinants of social commitment are (e.g. Bendapudi, Singh, & Bendapudi, 1996; Briggs, Landry, & Wood, 2007; Michel & Rieunier, 2012; Wymer & Starnes, 2001). Despite the abundant research, interest in the matter remains as keen as ever, the truth being that individuals simply do not respond to new marketing strategies in the same way when it comes to NGOs (Lwin, Phau, & Lim, 2014).

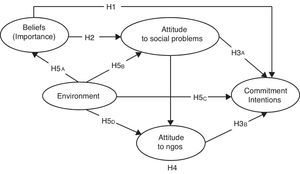

The current work focuses on the Third Sector and seeks to explain the process which prompts youngsters to commit socially, and specifically to cooperate actively with an NGO. Drawing on the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), we propose a model in which an awareness of social problems, attitudes towards such problems and towards NGOs, and youngsters’ environment interact to shape and define the process of social commitment. As set out in the Theory of Reasoned Action, our approach posits that a greater awareness of social problems generates a positive attitude towards them and that said attitude will in turn engender a greater likelihood of youngsters making a social commitment.

In order to complete the explanation of commitment, we add to this sequence the youngster's contextual or environmental effect and their attitude towards NGOs. The contextual effect aims to reflect the influence which the opinion and behaviour of other individuals close to the youngster might exert through the socialisation process on young people's decision to make a commitment (García Maínar, Marcuello Servos, & Sanz Gil, 2014). Attitude towards NGOs involves evaluating those intermediaries who transfer resources from donors to recipients (Bendapudi et al., 1996). NGOs are currently the most common vehicle for ensuring help reaches those who need it and as such their image may impact on an individual's social commitment and behaviour vis-à-vis helping (Bendapudi et al., 1996; Lwin et al., 2014; Michel & Rieunier, 2012; Sargeant, Ford, & West, 2006; Webb, Green, & Brashear, 2000).

We feel that the current work makes a two-fold interesting contribution to volunteer marketing literature. Firstly, the study focuses on young volunteers. Various works (McFarland & Thomas, 2006; Youniss, McLellan, & Yates, 1997) state that the participation of teenagers in volunteer work not only has short-term effects but also long-term consequences, since many of those who work as volunteers when they are young continue to do so when they are older. Youngsters represent the future of volunteer work. We know that they do not behave or respond in the same way as others to the work done by NGOs and yet there are comparatively far fewer studies into youngsters and volunteer work than there are into adults (Marta, Gugliemetti, & Pozzi, 2006; Veludo-de-Oliveira, Pallister, & Foxal, 2013).

Secondly, the work contributes to research on volunteer work by introducing into the Theory of Reasoned Action the effect of two variables which, in the light of prior literature, emerge as two very likely and powerful drivers of social commitment.

The work is structured as follows. We first present an overview of the literature exploring the various approaches used to address the topic. Section two then posits a behavioural model to account for social commitment. The third section describes the method used, and the fourth details the findings to emerge from the various statistical analyses employed. The paper concludes with the main conclusions to come out of the study and the managerial implications.

Review of the literatureThe qualitative change which has come about in nonprofit organisations has led to a major shift in the prospects for analysis thereof and has given rise to the urgent need to adopt approaches and techniques used in the business world. Notions traditionally employed by scientific literature in the area of marketing have been applied to the Third Sector. With nonprofits as a whole, and NGOs in particular, having consolidated their key role as social, political and economic actors, interest in exploring them has grown substantially amongst marketing scholars. This is reflected in the numerous studies carried out aimed at gauging the suitability of applying to NGOs the models and theories developed for the business sector.

In marketing, one of the main focuses of attention has been volunteers, the reason being that “if volunteers did not exist, most social campaigns would come to an abrupt halt, as it is volunteers who are the driving force behind this social behaviour and behind many social campaigns” (Kotler & Roberto, 1992). For many NGOs, recruiting volunteers is one of their main tasks and one in which marketing can clearly make a major contribution (Yavas & Riecken, 1997).

Work in this area falls into two main lines of research. The first focuses on segmenting the volunteer market in terms of socio-demographic and psychographic characteristics (in the terms set out by Sargeant et al., 2006, extrinsic and intrinsic factors which can impact volunteer behaviour). Socio-demographic characteristics comprise variables such as age (e.g. Chacón & Vecina, 2002; García Maínar et al., 2014; Kottasz, 2004; Lwin et al., 2014), sex (e.g. Chacón & Vecina, 2002; Chrenka & Jasper, 2003; García Maínar et al., 2014; Kottasz, 2004; Lwin et al., 2014; Rooney, Mesch, Chin, & Steinberg, 2005), academic qualifications (e.g. García Maínar et al., 2014; Lwin et al., 2014; Reed & Selbee, 2000), income and social class (e.g. Bryant, Jeon-Slaughter, Kang, & Tax, 2003; García Maínar et al., 2014; Lwin et al., 2014; McClelland & Brooks, 2004).

Findings indicate that, generally speaking, those who volunteer are more likely to be female as well as better-educated and with a higher level of income in addition to being less materialistic than those who do not volunteer. Nevertheless, certain studies have evidenced that this cliché is changing and that volunteer profile is linked to the nature of the particular sector to which the NGO belongs (Lwin et al., 2014; Shelley & Polonsky, 2002). By way of an example, organisations which focus on helping the elderly prove less of an incentive for youngsters between 16 and 18 whereas organisations devoted to helping the third world or the environment appeal more to this particular age bracket (Kottasz, 2004).

Psychographic characteristics refer to variables such as the individual's values, motivation, personality or self-esteem and self-concept. All of these variables may be considered intrinsic determinants of volunteers (Sargeant et al., 2006). In this particular group, amongst the variables which have been seen to have a significant effect on helping behaviour, we find self-concept and self-esteem (e.g. Beerli et al., 2004; Briggs et al., 2007), moral identity (Reed, Aquino, & Levy, 2007), empathy, (e.g. Neuberg et al., 1997), feelings such as fear, blame or pity (e.g. Amos, 1982) or altruism, selfishness and social obligation (e.g. Omoto & Snyder, 1995). For this group of variables, we highlight the many works that focus on studying volunteers’ motivation (e.g. Francis, 2011; Gage & Thapa, 2012). Most are based on Omoto & Snyder's Volunteer Process Model (1995) and explore the motives behind social commitment using the Volunteer Functions Inventory scale (VFI) developed by Clary et al. (1998) (Wilson, 2012). The array of fields explored and the different approaches used in the various studies have all led to the emergence of a large number of wide-ranging motives which, as is the case of socio-demographic variables, seem to dispose individuals towards becoming volunteers only in specific cases and depending on the particular sector to which the NGO belongs. Wymer (1997) and Wymer and Starnes (2001) for instance point to the fact that older volunteers are more driven by altruistic reasons than those who are younger.

The other line of research addressing volunteerism and donors in marketing aims to test and extend more complex behaviour and relations marketing models to the nonprofit sector. Judging by the number of studies published, considerably less time and effort has been devoted to this area than to the issue of segmentation. Prominent works to emerge in this field include Bendapudi et al. (1996), Webb et al. (2000), Wymer and Starnes (2001), Wisner, Stringfellow, Youngdahl, and Parker (2005), Briggs et al. (2007), Ranganathan and Henley (2008), Vecina, Chacón, Sueiro, and Barrón (2012), Veludo-de-Oliveira et al. (2013) and Lee, Won, and Bang (2014) as well as research based on the commitment-trust model developed by Morgan and Hunt (1994), Sargeant and Lee (2004), MacMillan, Money, Money, and Downing (2005) and Sargeant et al. (2006).

Bendapudi et al. (1996) merge relevant research on marketing, economics, sociology and social psychology in an effort to further theoretical understanding of helping behaviour and posit a model which serves as a guide for NGOs. Wymer and Starnes (2001) developed a model of the determinants governing the intention to cooperate. The works of Webb et al. (2000), Briggs et al. (2007), and Ranganathan and Henley (2008), propose models based on the attitude-behaviour relationship to analyse determinants of helping behaviour. Webb et al. (2000) specifically aim to develop a scale for measuring attitudes to giving, differentiating two dimensions, attitude to the organisation and attitude to the act of helping. Briggs et al. (2007) show that volunteers’ attitude to the task they are engaged in acts as a mediating variable between, on the one hand attitude to the organisation, materialism and the individual's self-esteem, and on the other volunteer helping behaviour. Ranganathan and Henley (2008) study the determinants of the intention to give, and find that attitude to NGOs is the strongest driver.

Veludo-de-Oliveira et al. (2013) and Lee et al. (2014) compare a model based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour. The former team find that the subjective norm is the variable which most accounts for volunteer work over time, whereas in the latter of these works perceived behavioural control emerges as the strongest determinant of the intention to cooperate with the organisation again.

The works of Wisner et al. (2005) and Vecina et al. (2012) focus on an analysis of volunteer satisfaction. Wisner et al. (2005) report a close link between volunteer satisfaction with their work and loyalty towards the organisation. Vecina et al. (2012) investigate the relation between engagement, volunteer satisfaction, organisational commitment and intention to remain. Their findings reveal a complex causal relation between engagement, satisfaction and volunteer commitment to account for the intention to remain.

Finally, studies addressing the link between donors or volunteers and the organisation evidence that in the third sector the concepts of trust and commitment also play a key role, but that their role and relations differ to those previously pinpointed in the behaviour context (Bennett & Sargeant, 2005).

The proposed model and hypothesesSocial marketing has generally been described as the design, implementation and control of programmes calculated to influence the acceptability of social ideas (Kotler & Zaltman, 1971). Social marketing may be approached from various perspectives such as ecological marketing and nonprofit marketing provided there is a common core underlying the discipline or subject matter.

Numerous research works have explored and evidenced the impact of attitudes on consumer behaviour (Sheppard, Hartwick, & Warshaw, 1988), particularly from the standpoint of social psychology. It is therefore logical that since the dawn of social marketing in the 1950s, models should have been applied and refined in an effort to account for consumer behaviour when faced with varying social problems based on the link between attitudes and behaviour. Works such as Webb et al. (2000), Wymer and Starnes (2001), Briggs et al. (2007), Ranganathan and Henley (2008) or Veludo-de-Oliveira et al. (2013), who explore how and to what extent attitude impacts helping behaviour, are the exception. Despite the many studies conducted to date, our knowledge and understanding of attitudes to social issues and charity or nonprofit organisations remain scarce.

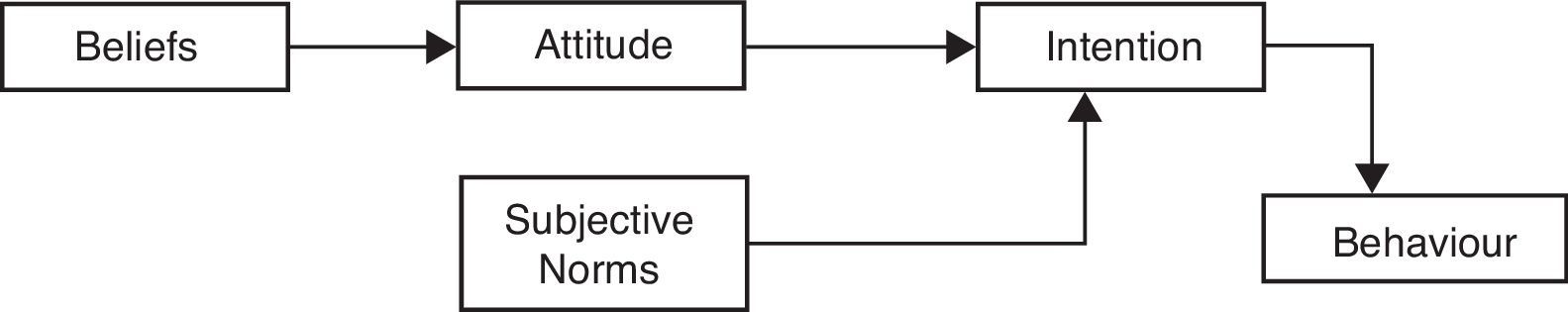

Prominent amongst social psychology theories addressing attitude formation, commonly known as expectancy-value theories, is Ajzen & Fishbein's Theory of Reasoned Action (1980). This theory develops a model to predict any relation between attitude and behaviour in which the mediating effect of the intention variable proves crucial. The intention variable is the most closely linked to behaviour and the most likely means through which certain attitudes may influence particular behaviours, thus proving the best predictor or indicator of a given behaviour. This theory posits two kinds of explanatory variables for intention: attitude to behaviour and the subjective norm. Regarding the former entity, attitude is deemed the individual's willingness impacting the development of a particular behaviour and is determined by an individual's beliefs towards behaviour and by the evaluation made of or importance attached to these beliefs. With regard to the latter variable, the subjective norm reflects the impact on the individual of the opinion of others such as family or friends ultimately influencing the individual's behaviour.

As Fraj & Martinez point out (2003), the Theory of Reasoned Action is based on two premises. The first assumes the existence of rationality and a systematic use of available information, the second stating that individuals take account of the consequences of their actions before deciding whether to commit themselves or not to a specific course of behaviour.

Fig. 1 shows the model for the theory and reflects how the four core concepts are linked. Beliefs influence attitude, attitude and subjective norms in turn determining behaviour through intention. Although intention is seen as the best predictor for behaviour, it is the analysis of attitudes and subjective norms which enable us to gain a deep insight into the real causes underlying behaviour.

Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980).

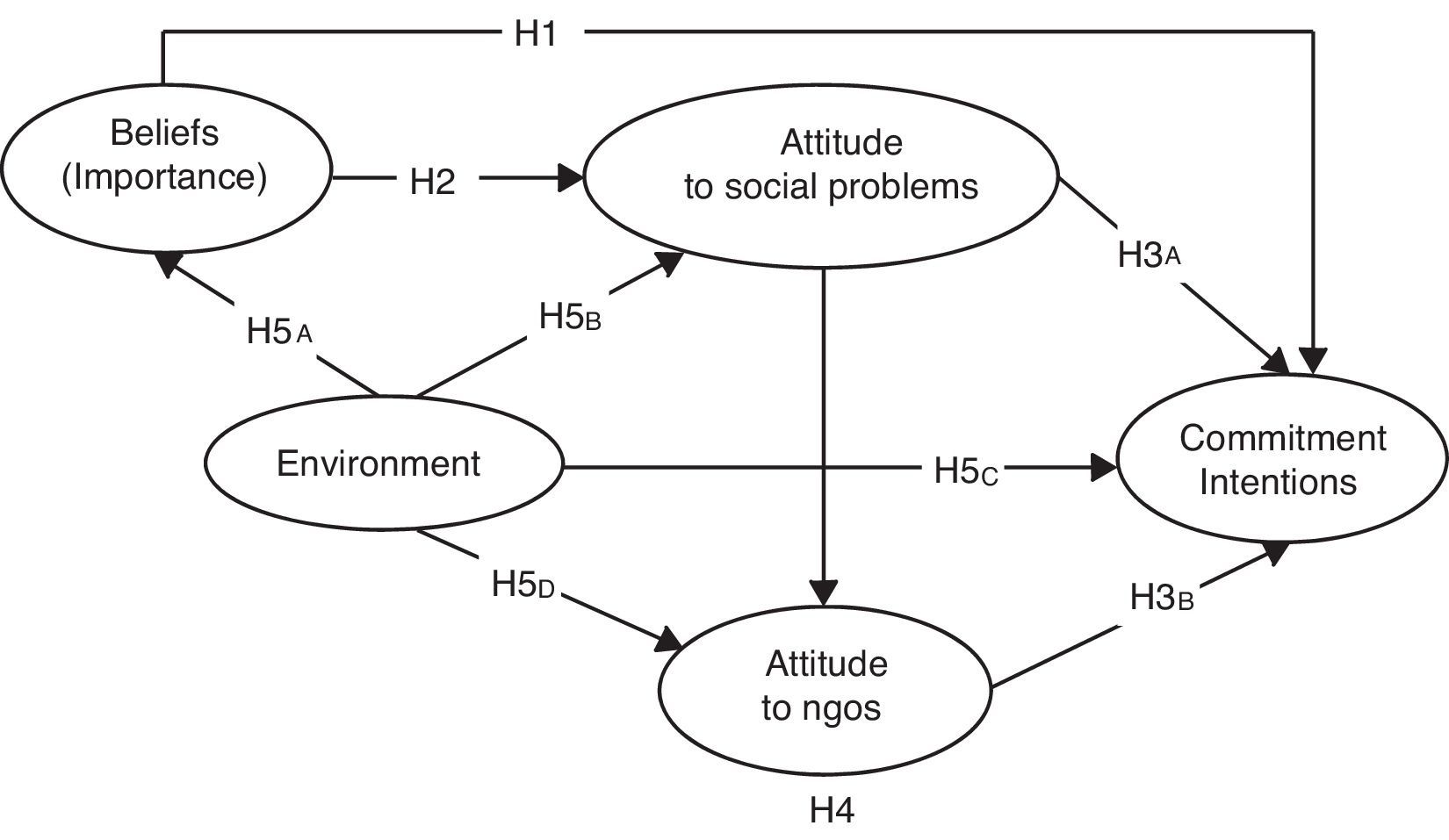

With our stated goal of accounting for the social commitment manifested by youngsters, and following on from the classical structure of social psychology and more specifically the Theory of Reasoned Action, we propose the model shown in Fig. 2.

The dependent variable in our model corresponds to the behaviour intention variable in the Theory of Reasoned Action. Behaviour intention in this theory is defined in general terms as the obligation undertaken vis-à-vis a given behaviour. Given that the research is framed in the area of non-government organisations, we equate said behaviour intention to the social commitment intention variable.

Bendapudi et al. (1996) define helping behaviour as that which improves the wellbeing of someone in need, providing help in exchange for little or no reward. This may take the shape of monetary donations, giving blood or donating organs, or devoting time and work. Research into fundraising distinguishes two aspects of help behaviour: the likelihood that an individual will give and the size of the donation (Garner & Wagner, 1991; Peltier, Schibrowsky, Schultz, & Davis, 2002; Webb et al., 2000). Here, we have constructed the variable reflecting the level of social commitment multiplying the likelihood of volunteering to help an organisation by the amount of time a subject is willing to devote to volunteer work.

The beliefs variable reflects an individual's values and concerns regarding social problems. The level of awareness of social problems and the importance attached to various kinds of problems merge to shape the individual's social conscience. In social marketing literature, findings on the relation between awareness or understanding and behaviour have proved inconsistent. Works such as Hoch and Deighton (1989), Park, Mothersbaugh, and Feick (1994), Chan and Yam (1995) or Chan (1999) and Chan and Lau (2001) have shown a positive link between awareness and behaviour, whereas others such as Arbuthnot and Lingg (1975) and Schahn and Holzer (1990) have argued that a high degree of awareness does not necessarily entail any specific decision to act. Despite this empirical inconsistency affecting the relation between the two, as it seems clear that a social conscience is an essential requirement for social commitment, we posit the following hypothesis:H1Individuals who are more aware of social problems will display a greater degree of commitment.

In the current work, the attitude variable in the model proposed is equated to the attitude variable in the Theory of Reasoned Action. Thus, as proposed in this theory, we interpret attitude as an acquired willingness to respond consistently, favourably or unfavourably to a given object (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) shaped by individuals’ beliefs towards that object and the weight attached to those beliefs. Indeed, numerous works maintain that a greater degree of awareness or deeper understanding leads to a more positive attitude to a certain behaviour (Chan & Lau, 2001; Ramsey & Rickson, 1976; Synodinos, 1990). We therefore posit the following hypothesis:H2Individuals who are more aware of social problems will display a more positive attitude towards them.

Both the Theory of Reasoned Action and previous research suggest the need to distinguish between attitude towards conduct or behaviour and attitude towards the object. As a result, and following the recommendation by Webb et al. (2000) and Briggs et al. (2007), when assessing the impact of attitudes on social commitment and help behaviour, we distinguish between attitude to social problems and attitude to organisations. Attitudes towards social problems tend to be more general than attitudes towards NGOs (Webb et al., 2000). Both types of attitude are key predictors of behaviour as evidenced by nonprofit marketing studies which have explored, on the one hand, attitude towards donation (e.g. Burnkrant & Page, 1982; McIntyre et al., 1987; Pessemier, Bemmaor, & Hanssens, 1977), and on the other, attitude to NGOs (Harvey, 1990; Schlegelmilch & Tynan, 1989).H3AIndividuals who display a more positive attitude to social problems will demonstrate a higher degree of social commitment.H3BIndividuals who display a more positive attitude to NGOs, will demonstrate a higher degree of social commitment.

Although we feel that attitude to social problems and attitude to organisations are different determinants of social commitment, they are not independent. For those who display positive attitudes towards social problems, cooperating with NGOs is just one of the ways in which the goal of helping others can be achieved (Webb et al., 2000). Forming attitudes to social problems involves interiorising a series of moral values and personal norms. Inner values can arouse feelings of moral obligation regarding the decision to help others or not. By contrast, attitude to NGOs involves appraising an intermediary, an organisation, which transfers resources from the donor to the beneficiary (Bendapudi et al., 1996). NGOs are a vehicle through which help can be provided to the needy and their image may impact individuals’ social commitment and helping behaviour (Bendapudi et al., 1996; Briggs et al., 2007; Michel & Rieunier, 2012; Ranganathan & Henley, 2008; Sargeant et al., 2006; Webb et al., 2000). Volunteers will neither contribute to nor cooperate with organisations they do not trust.

Attitude to organisations plays a mediating role in engendering social commitment as it channels part of the effect of attitude to social problems towards the intention to cooperate with the organisation. However, its function in the process should not be seen merely as that of a conduit of effects from one variable to another. Being a mediator involves much more. The mediating variable transforms the influence of the variable that converges into it and may alter its ultimate effect on social commitment (Baron & Kenny, 1986).H4Attitude to NGOs acts as a mediating variable in the link between attitude to social problems and social commitment.

Finally, based on the Theory of Reasoned Action we propose the effect of the opinions of others on an individual's behaviour. These effects form part of the subjective norm which, according to the theory, impacts behaviour intention. As in our work the subject we analyse is a youngster, Ajzen & Fishbein's concept of the subjective norm is closely linked to the socialisation process. Socialisation in consumer behaviour literature is defined as the process through which youngsters acquire relevant skills, knowledge and attitudes enabling them to function and survive in the marketplace (Moschis & Churchill, 1978). Parents, colleagues and mass media are the main socialisation actors (García Maínar et al., 2014). As a result, from a wider viewpoint it seems reasonable to assume that all the pressure surrounding youngsters should not only directly affect their behaviour but should do so through awareness and attitudes. In other words, social understanding as well as awareness and individuals’ attitudes will be influenced by their environment. We thus propose that:H5AA more favourable environment to commitment will have a positive impact on an individual's awareness of social problems.H5BA more favourable environment to commitment will have a positive impact on an individual's attitude to social problems.H5CA more favourable environment to commitment will have a positive impact on an individual's social commitment.H5DA more favourable environment to commitment will have a positive impact on an individual's attitude to NGOs.

MethodologyTo achieve our goal, we carried out 488 surveys amongst 16 to 18 year-old first and second year upper secondary school students at nine high schools in Valladolid (46% male and 53% female), in conjunction with the Aula Social (Social Classroom) non-government organisation. Schools were chosen taking into account their location so as to cover as wide an area of the city as possible and thus ensure sample variability.

The questionnaire used for the research was divided into four sections. The first section measured the extent to which youngsters were aware of social reality and the problems it faces. This particular section was divided into two parts: the first dealing with the most common problems facing Spain, whilst the second addressed wider issues in the more privileged countries. Another large section of the questionnaire focused on gaining an insight into the attitudes youngsters display to social problems as a whole and to NGOs in particular. The third section posed a series of questions aimed at exploring the interviewees’ background and gathering information on the level of awareness of those in their immediate environment. The final section sought to gauge their intention to become involved as volunteers in an NGO and to ascertain how much of a commitment they were prepared to make.

As regards measuring the various concepts involved in the study, we based our approach on the works of Webb et al. (2000) and Briggs et al. (2007), although we also used scales from other areas such as ecological marketing. In truth, research into volunteerism in nonprofit marketing has paid little attention to developing reliable and valid measuring tools. Much research has relied on its own measuring scales and complex concepts have often been measured using a single indicator (Webb et al., 2000). The appendix contains a list of the measuring indicators used for each variable followed by a description of the measurement of each concept.

Beliefs: In an effort to grasp the concept defined by the Theory of Reasoned Action and to measure their values and concerns vis-à-vis social problems, youngsters in the sample were asked to judge from 0 to 10 the importance they attached to eight different social problems at a global (more general) as well as a national scale (more specific).

Attitude to social problems: The scale measuring attitudes to social problems was designed specifically for this study. Based on works such as De Pelsmacker, Janssens, Sterckx, and Mielants (2006), Webb et al. (2000), and Ranganathan and Henley (2008), we included aspects which the literature relates to a favourable or unfavourable predisposition towards helping behaviour: resignation (belief that personal effort is in vain), scepticism (doubts concerning the reason behind helping behaviour) or inclination towards action (conviction that it is possible to do something coupled with a wish to do it). In this case, youngsters were asked to express their level of agreement or disagreement with a series of statements, valuing them on a 3-point Likert scale.

Attitude to NGOs: To measure attitude to organisations, we based our approach on the work of Bendapudi et al. (1996), the scale developed by Webb et al. (2000) and the findings obtained by Sargeant et al. (2006), and Ranganathan and Henley (2008). This led us to measure attitude using indicators linked to organisations’ image, reflecting aspects such as the recognition of the importance of their work, clear management, the ability to project values as well as the efficiency and effectiveness with which they work towards accomplishing their goals. We also used 3-point Likert scales here.

Environment: Aims to reflect the degree of social pressure that the individual perceives when acting. Bearing in mind that the sample is composed of youngsters and that the groups which are most likely to influence them are their parents and friends, we measured this concept through two indicators which reflect to what extent the interviewees’ family and friends are involved in volunteer work, again using a 3-point Likert scale.

Commitment: The degree of social commitment was constructed multiplying the intention to cooperate in volunteer work with an NGO (five-point scale) by the amount of time the individual is willing to devote (five-point scale). The decision to measure commitment in this way is based on the work of Briggs et al. (2007) and on the research into fundraising conducted by Garner and Wagner (1991), Webb et al. (2000) and Peltier et al. (2002), all of which are studies that distinguish two aspects of helping behaviour: the likelihood of an individual making a donation and the size of the donation.

Analysis and findingsTo test the proposed model empirically, we used a structural equation analysis based on partial least squares (PLS) estimation. PLS is more flexible with regard to the measuring scales used as it enables analysis of continuous, ordinal and even categorical variables and does not require the variables to adjust to a normal distribution (Falk & Miller, 1992). A further reason for employing this model is that it allows latent variables created from formative indices to be used (Chin, 1998). In both cases, the features of this estimation procedure fit the particular requirements of the research in hand.

Using the partial least squares approach, in order to verify the hypotheses proposed in the model the so-called path coefficients need to be analysed applying three kinds of criteria; sign, size and significance, the latter estimated from the Student t value. To do this, the chosen software applies a resampling procedure known as bootstrapping which generates a series of samples from an original sample. Estimations of the final parameters are calculated as the mean of the estimations obtained in all of the samples generated, enabling their significance to be determined from the distribution of the parameters estimated around the mean. The computer application used was SmartPLS v3.0 (Ringle et al., 2014).

Estimating the measuring modelAll the variables in the model, apart from commitment which is measured using a single indicator, are considered to be formative constructs. A formative index is a latent construct composed of its measuring indicators, in other words a lineal combination thereof. Such indicators are causes or antecedents of the latent variable, characteristics defining the concept in hand and not manifestations of the concept being measured as occurs with reflective indicators. In marketing literature, there is general consensus that attitude is the aggregate summary of the evaluations of an object (Malhotra, 2005). The conceptual and empirical significance of the variables in the Theory of Reasoned Action model–beliefs, attitudes and subjective norm–fully fits that of a formative or aggregate index. Attitude, however, has traditionally been measured using reflective scales, although few studies warn of the potential dangers of automatically applying conventional measuring techniques without taking account of the true nature of the relation between constructs and measuring scales used (Diamantopoulos & Winklhofer, 2001; Jarvis, Mackenzie, & Podsakoff, 2003). In their review, Jarvis et al. (2003) found that 28% of the studies analysed used reflective modelling for latent concepts whose indicators were in fact formative.

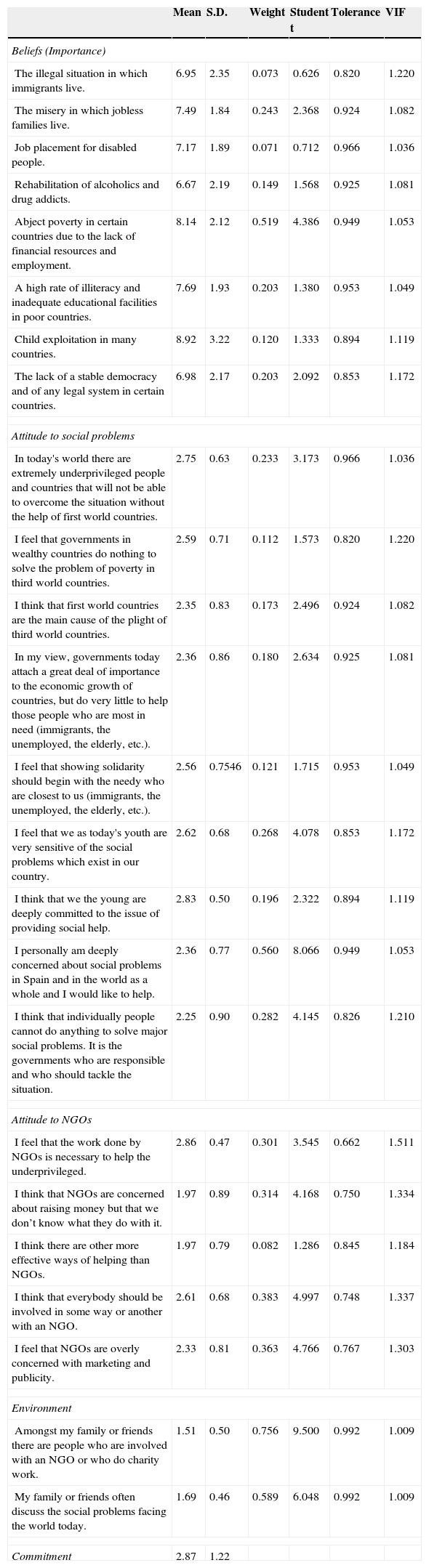

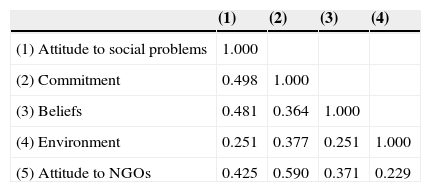

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for each measuring indicator, the estimation of the measuring model (weights) and the multicollinearity diagnostic statistics.

Measurement of variables and descriptive statistics.

| Mean | S.D. | Weight | Student t | Tolerance | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beliefs (Importance) | ||||||

| The illegal situation in which immigrants live. | 6.95 | 2.35 | 0.073 | 0.626 | 0.820 | 1.220 |

| The misery in which jobless families live. | 7.49 | 1.84 | 0.243 | 2.368 | 0.924 | 1.082 |

| Job placement for disabled people. | 7.17 | 1.89 | 0.071 | 0.712 | 0.966 | 1.036 |

| Rehabilitation of alcoholics and drug addicts. | 6.67 | 2.19 | 0.149 | 1.568 | 0.925 | 1.081 |

| Abject poverty in certain countries due to the lack of financial resources and employment. | 8.14 | 2.12 | 0.519 | 4.386 | 0.949 | 1.053 |

| A high rate of illiteracy and inadequate educational facilities in poor countries. | 7.69 | 1.93 | 0.203 | 1.380 | 0.953 | 1.049 |

| Child exploitation in many countries. | 8.92 | 3.22 | 0.120 | 1.333 | 0.894 | 1.119 |

| The lack of a stable democracy and of any legal system in certain countries. | 6.98 | 2.17 | 0.203 | 2.092 | 0.853 | 1.172 |

| Attitude to social problems | ||||||

| In today's world there are extremely underprivileged people and countries that will not be able to overcome the situation without the help of first world countries. | 2.75 | 0.63 | 0.233 | 3.173 | 0.966 | 1.036 |

| I feel that governments in wealthy countries do nothing to solve the problem of poverty in third world countries. | 2.59 | 0.71 | 0.112 | 1.573 | 0.820 | 1.220 |

| I think that first world countries are the main cause of the plight of third world countries. | 2.35 | 0.83 | 0.173 | 2.496 | 0.924 | 1.082 |

| In my view, governments today attach a great deal of importance to the economic growth of countries, but do very little to help those people who are most in need (immigrants, the unemployed, the elderly, etc.). | 2.36 | 0.86 | 0.180 | 2.634 | 0.925 | 1.081 |

| I feel that showing solidarity should begin with the needy who are closest to us (immigrants, the unemployed, the elderly, etc.). | 2.56 | 0.7546 | 0.121 | 1.715 | 0.953 | 1.049 |

| I feel that we as today's youth are very sensitive of the social problems which exist in our country. | 2.62 | 0.68 | 0.268 | 4.078 | 0.853 | 1.172 |

| I think that we the young are deeply committed to the issue of providing social help. | 2.83 | 0.50 | 0.196 | 2.322 | 0.894 | 1.119 |

| I personally am deeply concerned about social problems in Spain and in the world as a whole and I would like to help. | 2.36 | 0.77 | 0.560 | 8.066 | 0.949 | 1.053 |

| I think that individually people cannot do anything to solve major social problems. It is the governments who are responsible and who should tackle the situation. | 2.25 | 0.90 | 0.282 | 4.145 | 0.826 | 1.210 |

| Attitude to NGOs | ||||||

| I feel that the work done by NGOs is necessary to help the underprivileged. | 2.86 | 0.47 | 0.301 | 3.545 | 0.662 | 1.511 |

| I think that NGOs are concerned about raising money but that we don’t know what they do with it. | 1.97 | 0.89 | 0.314 | 4.168 | 0.750 | 1.334 |

| I think there are other more effective ways of helping than NGOs. | 1.97 | 0.79 | 0.082 | 1.286 | 0.845 | 1.184 |

| I think that everybody should be involved in some way or another with an NGO. | 2.61 | 0.68 | 0.383 | 4.997 | 0.748 | 1.337 |

| I feel that NGOs are overly concerned with marketing and publicity. | 2.33 | 0.81 | 0.363 | 4.766 | 0.767 | 1.303 |

| Environment | ||||||

| Amongst my family or friends there are people who are involved with an NGO or who do charity work. | 1.51 | 0.50 | 0.756 | 9.500 | 0.992 | 1.009 |

| My family or friends often discuss the social problems facing the world today. | 1.69 | 0.46 | 0.589 | 6.048 | 0.992 | 1.009 |

| Commitment | 2.87 | 1.22 | ||||

To conduct the corresponding analyses, indicators expressed negatively were recoded positively.

To evaluate the measuring model for formative indexes, it is the weights and not the factorial loads that are examined, since the goal is to interpret each indicator's contribution to the formation of the corresponding variable. If we look at the estimated weights of the measuring indicators shown in Table 1, we see that abject poverty, misery, marginalisation, the lack of a stable democracy and absence of justice in certain countries are the items with the greatest impact on the formation of the beliefs variable. The remaining items make no significant contribution to the formation of the construct. The interpretation seems to be that problems such as immigration, the working environment of the disabled, rehabilitation of drug-addicts, illiteracy or child exploitation, lack any relevant weight in the social conscience. Regarding attitude to social problems, all the indicators measured with the exception of the items “I feel that governments in wealthy countries do nothing to solve the problem of poverty in third world countries” and “I feel that showing solidarity should begin with the needy who are closest to us”, make a significant contribution to the general index. Indicators contributing to the formation of attitude to NGOs are those which deal with the need for cooperation, clear management, importance of their work and efficiency. How effective these organisations are does not seem to be important in attitude formation. Finally, the two indicators measuring the social pressure of the environment prove relevant in the index's composition.

Regarding the scale validation procedure, since the scale does not need to be internally consistent when defining the formative constructs, traditional reliability analysis and reflective scale validity procedures do not prove adequate (Bagozzi, 1994). Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer (2001) recommend conducting multicollinearity diagnosis to ascertain the validity of the formative indicators. A formative measure is essentially a multiple regression in which the construct represents the dependent variable and the indicators are the predictors. If the correlation amongst the indicators generates multicollinearity, the resulting coefficients may prove unstable, leading the index constructed to be less reliable. Table 1 shows the tolerance values and the variance inflation factor (VIF). These values show that no multicollinearity problems exist in the construction of the formative indexes used in our analysis. Finally, as can be seen in Table 2, given that the values of the correlation coefficients amongst latent variables are in no case above 0.6, we may assume discriminant validity (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Jarvis, 2005).

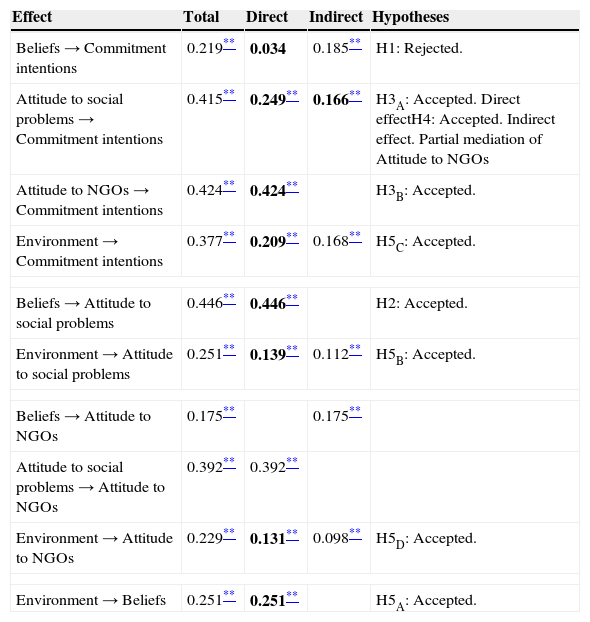

Estimating the structural modelAs can be seen in Table 3, findings from the analysis bear out most of the hypotheses posited in the theoretical model. The only hypothesis which was not proved was hypothesis H1, youngsters’ beliefs concerning social problems, their social conscience having no direct impact on commitment. This finding is not surprising since in the Theory of Reasoned Action beliefs by themselves do not engender behaviour intention, an effect which is rather reflected through the attitude variable. Analysis of the structural equations does, however, substantiate hypothesis H2. We were thus able to confirm that, as stated in the theory, beliefs affect attitudes. In other words, the greater the degree of social awareness a youngster develops, the more positive the attitude will be to social problems. We also confirmed the H3 block of hypotheses, which spans hypotheses H3A and H3B, enabling us to affirm that more positive attitudes to social problems and to NGOs are more likely to lead to commitment. The findings also bear out hypothesis H4, confirming the mediating role of attitude to NGOs between attitude to social problems and social commitment, although there is no full mediation (VAF=40%) (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2014, p. 224). Finally, environment seems to play a key role in the proposed model. Hypotheses H5A, H5B, H5C and H5D are confirmed, as there is a significant and positive relation between youngsters’ environment and beliefs, attitudes and behaviour intention. It should be remembered that the sample is composed of youngsters who are at a stage in their development when the effect of socialisation is at its strongest. In sum, the model proposed provides a good reflection of how the process of social commitment develops, in general terms the determinants considered accounting for 45.5% of the dependent variable.

Total, direct and indirect effects.

| Effect | Total | Direct | Indirect | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beliefs→ Commitment intentions | 0.219** | 0.034 | 0.185** | H1: Rejected. |

| Attitude to social problems→ Commitment intentions | 0.415** | 0.249** | 0.166** | H3A: Accepted. Direct effectH4: Accepted. Indirect effect. Partial mediation of Attitude to NGOs |

| Attitude to NGOs→ Commitment intentions | 0.424** | 0.424** | H3B: Accepted. | |

| Environment→ Commitment intentions | 0.377** | 0.209** | 0.168** | H5C: Accepted. |

| Beliefs→ Attitude to social problems | 0.446** | 0.446** | H2: Accepted. | |

| Environment→ Attitude to social problems | 0.251** | 0.139** | 0.112** | H5B: Accepted. |

| Beliefs→ Attitude to NGOs | 0.175** | 0.175** | ||

| Attitude to social problems→ Attitude to NGOs | 0.392** | 0.392** | ||

| Environment→ Attitude to NGOs | 0.229** | 0.131** | 0.098** | H5D: Accepted. |

| Environment→ Beliefs | 0.251** | 0.251** | H5A: Accepted. | |

Significance levels are based on bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals.

The substantial growth in the so-called third sector during the 1990s and early years of the twenty-first century has meant that organisations in this sector have become the focus of much current academic research to such an extent that studies and concepts which had exclusively addressed the business sector in previous years have now shifted their attention to nonprofit organisations.

Adopting a marketing approach, we study donor and volunteer motivations and incentives as key characteristics, applying segmentation criteria and marketing strategies aimed at fundraising and time-giving which enable organisations to boost resources devoted to solidarity programmes and action. We note that insufficient effort has been dedicated to studying and advancing models which describe consumer behaviour applied to volunteer and donor participation that would allow nonprofit organisations to gauge the formers’ patterns of behaviour and develop policies to maximise effective capturing of resources.

Applying the Theory of Reasoned Action approach, the current work seeks to reveal the process through which a youngster decides to actively cooperate with an NGO. The determinants of commitment considered are those embraced by the Theory of Reasoned Action: beliefs, attitudes to social problems and to organisations, and the youngster's environment. The model posited reflects the interrelation between the determinant variables, giving shape to the process through which social commitment is forged.

The findings to emerge from the empirical study show that the model we propose proves valid to account for how social commitment is formed in youngsters. Young people's intention to cooperate with non-government organisations is defined directly by the attitudes they display towards the organisations themselves and to social problems as a whole as well as by youngsters’ immediate environment, and is influenced indirectly by their beliefs concerning social conflicts. Prominent is the twin role played by attitude to NGOs throughout the whole process. It is the strongest determinant in youngsters’ commitment and its mediating function converts much of the effect of a general attitude to social problems into an intention to cooperate. The findings confirm those obtained in previous studies. Specifically, they concur with Lee et al. (2014) for attitudes towards social problems and their effect on behaviour intention, the findings reported by García Maínar et al. (2014) with regard to the influence of the environment on social commitment, and those published by Ranganathan and Henley (2008) for the effect of attitude towards NGOs in social commitment.

Youngsters evidence a keen awareness of social problems existing at a national as well as international scale. The findings point to economic inequality (misery and poverty) as being the issue which raises greatest awareness amongst youngsters with regard to social problems. Although to a lesser degree, the lack of democratic stability and a legal system able to safeguard human rights in certain countries is another conflictive area which rouses a feeling of social awareness amongst youngsters. It is the major problems which persist in youngsters’ beliefs, those which appear the most alarming, long-lasting and abstract and which, whilst not appearing regularly in the media, have remained unresolved over a long time. Youngsters do not seem to be overly aware of the specific problems which surround them every day. Attaching importance to more global problems is typical of the early years of a social awareness which is no doubt stirred by the noblest causes, idealisms and unreachable goals. It is also worth mentioning that awareness of social problems is greater amongst youngsters who live and move in an atmosphere where a certain concern for these problems exists and where such issues are discussed.

Moreover, beliefs are reflected in the attitudes youngsters display to social problems. Today's youngsters seem highly critical and sceptical both of governments and institutions charged with solving problems and with themselves, feeling that today's youth shows little commitment. They blame imbalances on economically wealthier countries, and accuse them of showing little interest in solving these problems. Attitudes to social problems become more positive amongst youngsters who evidence individual concern and who feel the need and desire to lend a hand because they sense that their help will make a difference. More intense attitudes are also in evidence when youngsters live in an environment which disposes them towards displaying a greater concern because their family and friends exhibit such a commitment towards involvement in volunteering. In short, a deeper concern for social problems coupled with a feeling and conviction that individual help will contribute towards offsetting hardships at a global scale lead to stronger social commitment. If organisations are able to convince youngsters that by helping they can make a difference and can go some way towards improving the plight of the needy then these organisations will be strengthening youngsters’ intention to make a commitment.

Youngsters display a positive attitude to NGOs in that they feel active cooperation with these organisations to be beneficial, valuing the work they do and showing trust in how they are run, in short perceiving them to be efficient. This attitude is induced by two variables: attitude to social problems and living in an environment inclined towards social commitment. The twin role played by attitude to NGOs in the whole process should here be borne in mind. In addition to being the strongest determinant of commitment and acting as a mediator, of all the independent variables considered it is the factor which can most often be controlled by the organisation. In this respect, its impact on commitment proves crucial since the image an organisation conveys plays a role in attracting volunteers. It therefore comes as no surprise that one of the growing concerns of nonprofit organisations is currently to project their identity through an easy to manage brand which reflects how their image is perceived (Hankinson & Rochester, 2005). The next stage is to endow this brand with value.

Managerial implications, limitations and further researchWe feel that nonprofit organisations should make a concerted effort amongst youngsters when seeking to procure time donations. They need to remain aware that youngsters’ attitude to social problems and to organisations are the two variables which most impact the decision to become involved with an NGO. They must also become alert to the fact that there are already young people who are concerned with the problems of the society around them, who are conscious of the need to help organisations involved in providing for the needs of the most underprivileged. NGOs should not expect volunteers to come to them but should actively engage in enlisting help through marketing, particularly at a time when the amount of volunteer work is increasing but when the number of actual volunteers is not growing at a similar rate. The best approach may be to engage in direct communication with youngsters based on public relations activities in conjunction with schools in an effort to show youngsters how much they can contribute to a nonprofit organisation, thereby providing an outlet for their natural vitality and creativity. The advantage of direct communication for an NGO is that it can boost awareness of its existence amongst a group and may prove better at changing certain attitudes within the group, showing at the same time that the organisation is not just concerned with its image.

To conclude we set out the limitations of the work together with future lines of research. Firstly, by way of a limitation, we may point to the measuring scales used, which in part have been designed specifically for this work and which should have undergone an even stricter validation process than the one applied. This is especially true for the case of the beliefs variable, the validity of the content possibly raising certain doubts. As regards the formative indexes, the validity of the content is of particular importance, such that estimation of a MIMIC model, as recommended by Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer (2001) would have proved desirable. A further constraint, which in turn opens up a future avenue of exploration, is how the model is proposed, as it only extends to accounting for social commitment. Bearing in mind that the issue at hand is youngsters, it would seem reasonable to explore further and extend the model in an effort to ascertain which people continue to offer their support in the long term and why, or indeed why people cease to lend their support to volunteer work.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.