The purpose of this study is threefold. First, to test the experience economy framework in the context of a small island destination (SID) in order to determine if a music festival may be used as an experiential product to lure a cohort replacement. Second, to examine a music festival's experiential domains that may influence the overall experience of Generation Y (Gen Y) tourists. And, third to determine if the overall experience of Gen Y tourists who attend a music festival may predict their behavioral intentions to return to and recommend a SID. The study investigates whether a music festival may be used as an experiential attraction to draw the Gen Y market segment to a SID as a cohort replacement for the baby boomer generation. Structural equation modeling (SEM) is used to test the application of the experience economy framework to a generational cohort's behavioral intentions after the consumption of an experiential product in the context of a SID. The study suggests that in the case of Gen Y it may be necessary to reference economic value as part of the second-order construct for overall experience in order to predict future intentions.

El objetivo de este estudio tiene 3 vertientes. En primer lugar, probar el marco económico de la experiencia en el contexto de un destino a una pequeña isla, a fin de determinar si un festival de música puede utilizarse como un producto empírico para atraer a un grupo de sustitución. En segundo lugar, examinar los campos vivenciales de un festival de música que puedan ejercer una influencia sobre la experiencia global de los turistas de la Generación Y (Gen Y). Y, por último, determinar si la experiencia general de los turistas de la Generación Y que asistieron a un festival de música puede predecir sus intenciones conductuales para regresar y recomendar el destino insular. El estudio analiza si un festival de música puede utilizarse como un atractivo vivencial para atraer al segmento de mercado de la Gen Y a un destino insular, como grupo de sustitución de la generación del «baby boom». Se utiliza el modelo de ecuaciones estructurales (MES) para probar la aplicación del marco económico de la experiencia a las intenciones conductuales de un grupo generacional, tras el consumo de un producto vivencial en el contexto de un destino a una pequeña isla. El estudio sugiere que en el caso de la Gen Y puede ser necesario mencionar el valor económico como parte de la creación de segundo orden de la experiencia general, a fin de predecir las intenciones futuras.

Cohort replacement and generational succession are natural progressions of social life that influence consumer markets and product development (Alwin, 2002). As one generation fades, a replacement generation emerges that marketers must learn to attract through product development and promotional strategies. Prior to the introduction of Pine and Gilmore's (1998) experience economy, product development involved concerted efforts at the micro level to manufacture goods and design services that satisfied the needs and wants of generational markets possessing influential spending power.

However, in an era where consumers crave the distinct economic offerings of experiences (Manthiou, Lee, Tang, & Chiang, 2014; Oh, Fiore, & Jeoung, 2007), it is not only micro based firms that are compelled to upgrade their product offerings, but also macro based entities, such as destinations. If a destination is to remain competitive, then destination managers are required to upgrade their destination experiential offerings in accordance with the tastes and preferences desired by the next generational succession. This means that destinations are required to develop experiences that are representative of progressive economic value that are highly differentiated and that may be sold at premium prices.

It is well documented that the baby boomer generation comprises a large and important market segment in travel and tourism industries (Cleaver, Green, & Muller, 2000; Jang & Ham, 2009; Lehto, Jang, Achana, & O’Leary, 2008). The baby boomer generation is defined as those individuals that were born during the years of 1941–1960 (Glass, 2007). According to industry research, baby boomers spend approximately $157 billion on travel related expenses and rank travel as their number one leisure activity (UNWTO, 2009). Although this generation will remain an important target market for destination marketing organizations (DMOs) for several more decades, there is a need for DMOs’ management groups to consider the next generational succession of interest (Patterson & Pegg, 2009).

As the population of baby boomers continues to age, the result will be a shift in the age composition of tourists worldwide. Like any cohort, the new generation of tourists that emerges is expected to have varying tastes and preferences from that of the baby boomer generation due to lifetime events that influence the consumption patterns of each cohort (Li, Li, & Hudson, 2013). Therefore, if destinations are to remain competitive, it is important for DMOs to explore tourism related products that may encourage the next generation to visit a destination. This is especially critical for destinations that largely depend on the tourism industry as a major economic pillar to support the wider economy, such as small island destinations (SIDs).

SIDs’ economies are among the top 10 beneficiaries of tourism's activities thereby making these economies largely dependent on the performance of the tourism industry (Rivera, Semrad, & Croes, 2015; Schubert, Brida, & Risso, 2011). In order to secure a profitable industry performance, SIDs’ product offerings must reflect the current societal trend represented by the experience economy; and, DMOs must be aware of an encroaching need for cohort replacement as the most prominent generation ages. SIDs seem to be plagued by market rejuvenation problems due to tourism product portfolios that have been largely constructed to satisfy the tastes and preferences of the baby boomer generation (Croes, 2011).

The most homogeneous emerging generational succession with the most amount of influential spending power is that of Gen Y (Moscardo & Benckendorff, 2010, p. 50). Glass (2007) defines this cohort as individuals that were born during the years of 1977–1992. Thus, as the baby boomer cohort fades in its consumption of destination travel related experiences, DMOs may look toward Gen Y as the replacement cohort. The Gen Y cohort accounts for approximately 26% of the world's population with a spending power that exceeds $200 billion, and influences another $300–$400 billion in spending (UNWTO, 2009).

Therefore, it seems to behoove SIDs facing the market rejuvenation challenge to lure the newly emerging Gen Y segment to sample an island destination; thus, provoking them to revisit and recommend the SID to others while focusing on developing experiential product offerings. However, identifying the appropriate experiential product that would be appealing to Gen Y tourists may be difficult in the environmental context of a SID. This is because SIDs possess constrained market characteristics in which infrastructural developments that require capital investment and the permanent use of space must be carefully planned in order to ensure the maximum return on investment and use of potential economic linkages on the island (Croes, 2013; Rivera et al., 2015).

The standardization of tourism products resulting from globalization processes and pressures is taking place in an accelerated fashion all the while destinations are striving to distinguish themselves through the creation of unique tourist products that would allow them to remain competitive. A destination may establish distinctiveness through ‘creative tourism’ as suggested by Prentice and Andersen (2003) and Richards and Wilson (2005). Creative tourism includes festivals. Especially, those festivals that continue to add new elements each production year in order to keep the event interesting to the audience. The uniqueness of music festivals that occur in SIDs is that they encourage the interaction between tourists and local residents; thus, creating a sense of togetherness in a diversified environment.

For these reasons, music festivals may be an appropriate experiential product to add to a SID's current tourism product portfolio in so far as festivals are temporary attractions that do not require permanent space and resources, but do diversify a tourism product portfolio with that of experiences (Getz, 2008; McKercher, Sze Mei, & Tse, 2006). Therefore, products such as these may not take away from the current tourism product offerings or disrupt the market configuration that is appealing to the prominent tourist baby boomer market segment. In other words, the use of music festivals that appeal to the next generation succession may allow for a smooth market transition that does not abruptly change the market landscape that currently caters to the primary cohort.

The use of music festivals to attract Gen Y tourists may present a unique product development opportunity at relatively low risks for SIDs. The current study queries if music festivals may be used as experiential products to stimulate Gen Y tourists’ intentions to revisit and recommend an island destination. The study further investigates if the experience economy framework of Pine and Gilmore (1998) includes the appropriate experiential domains that may influence the overall experience of Gen Y tourists in the context of a SID.

The study assumes that because a music festival in a SID requires an attendee to travel to the host location and actually experience the product, the expectation of the tourists’ experience begins to evolve prior to the departure for the event (Oh et al., 2007). In other words, while the product is temporary in nature, the overall experience of attending a music festival in a SID is inclusive of the travel to the destination, the consumption of supporting related travel products, as well as the consumption of the core experience (festival). Therefore, based on the salient composition of travel related products, the reflective nature of Pine and Gilmore's (1998) experience economy framework that includes education, entertainment, escapism, and esthetics is a functional model to test in the context of a SID.

The main contribution of this research is to identify the experiential domains that form the overall experience for Gen Y tourists in the context of a SID using the Pine and Gilmore (1998) experience economy framework. The results may be useful to SIDs’ DMOs in the crafting and designing of experiential products in an effort to reach new markets through the process of generational succession. The next section reviews festivals as experiential products through the lens of the experience economy framework.

Literature reviewApplication of the experience economy framework to festivalsMainstream literature recognizes that the global society has entered the experience economy. The current study presupposes that the Gen Y cohort does not deviate in the desire to consume experience offerings. Therefore, the experience economy of Pine and Gilmore (1998) has been used as the baseline framework for this study.

According to Manthiou et al. (2014), there are limited empirical studies that have comprehensively analyzed experience in the festival context. Additionally, prior to Manthiou et al. (2014) who referenced the experience economy approach to festival marketing, no studies had systematically analyzed the festival experience in conjunction with theoretical support. The current study advances the application of Pine and Gilmore's experience economy (1998) in a similar fashion to that of the Manthiou et al. (2014) research. However, the current study has pointed interest in the experiential domains that are specifically important to the cohort Gen Y in the context of a music festival that occurs in a SID.

Pine and Gilmore's experience economy framework (1998) states that there are four different types of economic offerings (commodities, goods, services, and experiences). Consumer behaviorists have identified that the provocative difference between an experience economic offering and other offerings is that experiences are largely based on an intrinsic and personal interpretation of the experience that engaged the consumer. In other words, the interpretation of an experience product occurs within the individual who engaged in the experience in multisensory forms, thus resulting in some level of hedonic consumption (Gursoy, Spangenberg, & Rutherford, 2006). The other types of economic offerings (commodities, goods, and services) represent utilitarian consumption and do not stimulate a multisensory personal involvement when consuming the products (Ferdinand & Williams, 2013).

Experience domainsExperience products are comprised of four experiential domains that include: education, entertainment, escapism, and esthetics. According to Mehmetoglu and Engen (2011) these four domains highlight that an experiential product must provide opportunities that stimulate the multisensory connection for consumers to feel, learn, be, and do. In the context of a music festival, the multisensory active involvement of an attendee's connection with the surrounding festival environment must immerse the attendee in the event, thereby making attendees part of the music festival experience (Komppula & Lassila, 2015).

All four of the experience domains are defined in accordance with Manthiou et al's. (2014) application of the experience economy approach to festival marketing (for a complete topical survey see Manthiou et al., 2014). The current study has adopted the items that were used in the aforementioned research to measure each of the experiential domains. This means that education experiences are those solicited by festival attendees when they feel that their knowledge and skills may be improved through festival participation. Entertainment experiences are those that occur at festivals where people observe the activities and performances of others. Escapism is festival attendees’ desire to engage in different experiential contexts that are unlike their daily lives. And, esthetic experiences are defined as festival attendees’ overall evaluation of the festival's physical environment (Manthiou et al., 2014).

While the definitions of the domains remain the same to the Manthiou et al. (2014) research, the framework is applied within a unique context – a SID. According to Oh et al. (2007), it is recommended to test the experience economy paradigm within different tourism contexts in order to determine if everything that a tourist goes through to arrive at and consume an experiential product at the destination is actually the overall experience. Therefore, the causal construction of the experience framework is tested within the context of a music festival that occurs within a SID.

Experiential product characteristicsThe combined effects from the four experiential domains (education, entertainment, escapism, and esthetics) create what is referred to as the overall experience. Pine and Gilmore (1998) suggest that the most positive overall experiences will result from engaging consumers in memorable offerings that have an affective component. Morgan (2008) posits that in the case of festivals, the overall experience must be designed to create a unique and memorable experience in the attendee's mind. Getz (2002) echoes this claim by asserting that festivals will fail if they do not create unique and attractive positions in the minds of potential performers, attendees, and sponsors.

Pine and Gilmore also explain that the design of an experiential product must be worth the cost to the consumer. In other words, the price points for experiential products must be a function less of the cost of goods than of the value the consumer attaches to recall the experience consumption. Leask, Hassanien, and Rothschild (2011) also note that price is an influential characteristic on the overall evaluation of an experiential product due to consumers’ perceptions about obtaining value for money. Therefore, research seems to imply that festival attendees’ perceived value of a festival experience is representative of a cognitive trade-off between festival benefits and the cost to attend the festival.

In the context of festivals that occur in SIDs, attendees are required to travel to the destination by air or sea in order to consume the music festival. Therefore, it is only possible to attend a SID music festival as an international tourist or as an island resident. Thus, in the context of this research, there is a conceptual difference between Pine and Gilmore's (1998) definition of value and the current study's definition. Where Pine and Gilmore consider economic value to be a consequence of the experience between the experience outcomes and the cost, the current study considers the total cost and the time spent to arrive to the SID and consume the festival as the total economic value. This means that economic value may weigh more heavily in the context of SIDs than ordinary circumstances. Thus, the current study considers economic value to be the inclusion of total cost and the time spent to arrive to the island as a dimension of the overall experience.

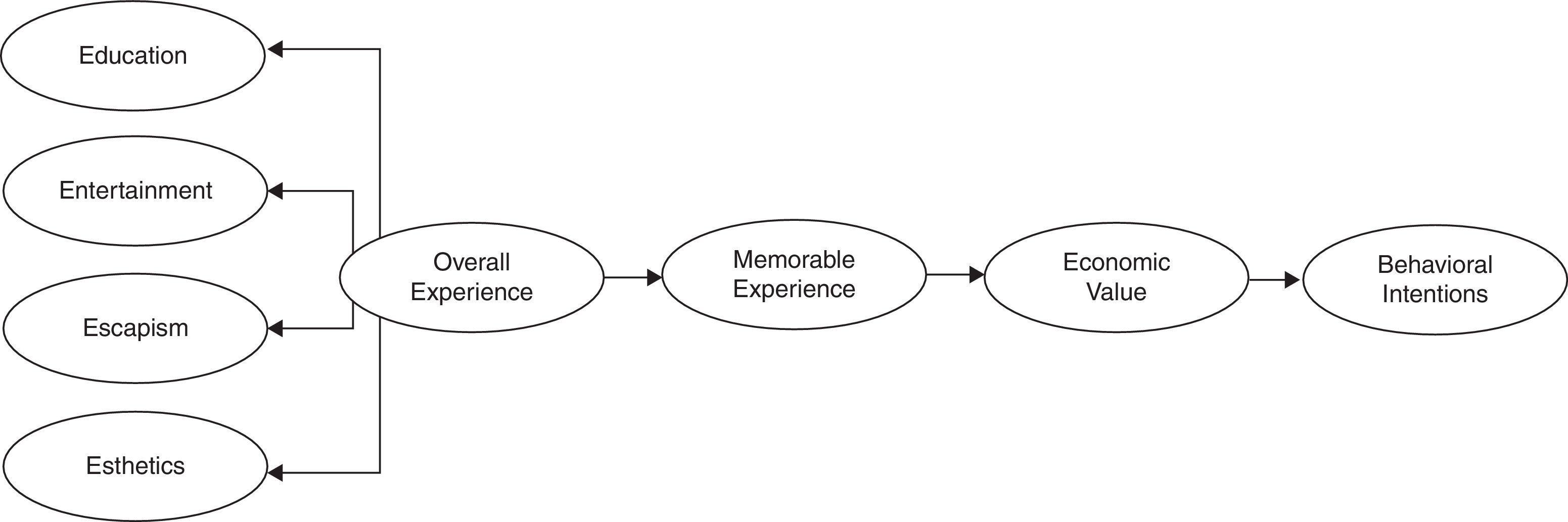

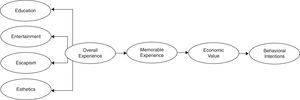

Based on Pine and Gilmore's suggestion (1998) to engage consumers in memorable experiences and past research, which demonstrated that well-constructed experiences at appropriate price points do influence consumers’ memories, the current study measures how overall experience, economic value, and memorable experiences may influence Gen Y music festival attendees’ behavioral intentions to return to or recommend a SID (Larsson & Faulkner, 2001; Manthiou et al., 2014; Tung & Ritchie, 2011). Fig. 1 represents the experience economy model derived from Pine and Gilmore (1998).

Experience economy framework (Pine & Gilmore, 1998).

The Pine and Gilmore model uses economic value as a mediating factor between overall experiences and memorable experiences. The current research contends that given the central focus of this study, which is to examine a music festival's experiential domains that influence Gen Y tourists’ behavioral intentions to return to and recommend a SID, that economic value may be an important component of the overall experience itself. Therefore, the current study recommends including economic value as part of the second-order construct for overall experience in order to predict future intentions.

This recommendation is based on two considerations that are specific to the context of this study. First, literature pertaining to Gen Y has revealed that the cohort expresses price conscious behaviors due to economic uncertainty that they have experienced (Abraham & Harrington, 2015; Leask, Fyall, & Barron, 2013). Second, as previously mentioned, the cost for Gen Y tourists to arrive to a SID and consume a music festival is much more than what a visitor may spend to attend a music festival on mainland. Therefore, the economic value for a music festival that occurs in a SID may be more intensive than in other circumstances.

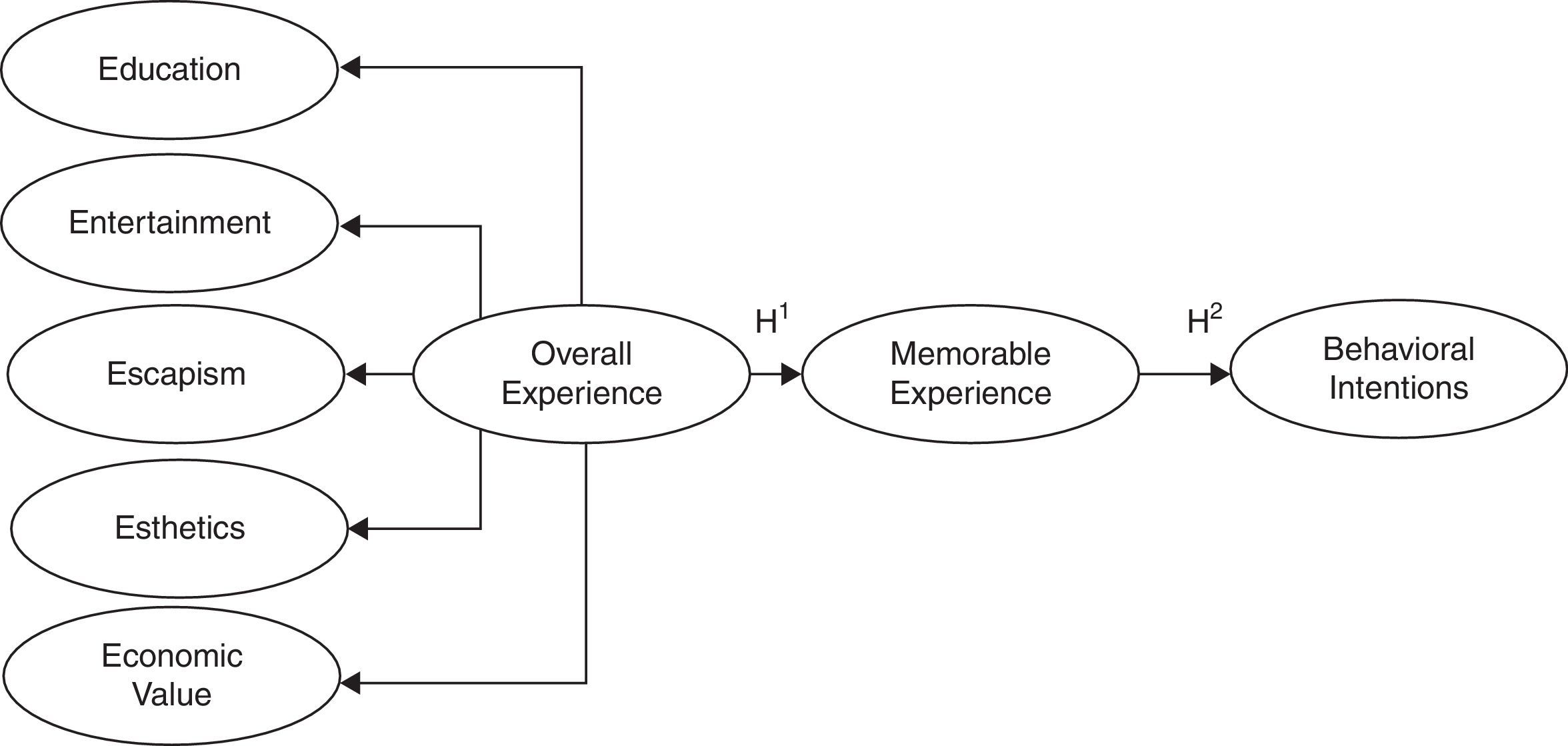

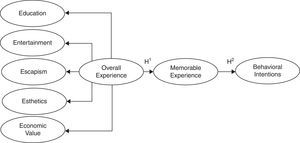

Based on these two considerations, the current study proposes an alternative research model in Fig. 2. The alternative model includes the original four domains of Pine and Gilmore: education, entertainment, escapism, and esthetics (4E's) but also includes economic value as a domain of the overall experience. Hence, the overall experience construct in this study's research model is comprised of 5E's (education, entertainment, escapism, esthetics, and economic value).

Research model and hypothesesThe research model used in this study is presented in Fig. 2. Overall experience is influenced by education, entertainment, escapism, esthetics, and economic value (5E's). The overall experience construct is a predictor of memorable experiences and memorable experiences are a precursor for Gen Y's behavioral intentions. The hypotheses are as follows:

H1: There is a positive relationship between overall experience and memorable experience.

H2: There is a positive relationship between memorable experience and behavioral intentions.

The Electric Music Festival made its debut in Aruba, September 6–8, 2013. Approximately 1900 music fans attended the three-day event. Electronic Dance Music (EDM) has become a popular music genre on a global scale with increasing economic significance. This genre of music has a special appeal with the Gen Y cohort and during the first decade of this century made a global reach across Gen Y (EVAR, 2012). The Aruba Tourism Authority and Amsterdam Dance Event jointly promoted the Electric Music Festival.

Aruba is a prominent tourism destination in the Caribbean. The island has one of the highest levels of income per capita in the region as well as human development (Croes, 2013). Aruba has a strong base of repeat visitors (approximately 60%), strong tourist satisfaction levels (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2011), and a high productivity rate measured by spending per arrival (US$160 per arrival) (Croes et al., 2011).

With regard to tourist arrivals, Aruba demonstrates two trends. First, the most predominant cohort arriving to Aruba is the baby boomer segment with tourists who are 65 years and older. Second, Aruba demonstrates a negative trend with regard to the presence of younger generations arriving to the island (Croes et al., 2011). The most recent tourism master plan for the island unearthed cohort replacement and generational succession as the most prominent strategic challenges in the years to come (Croes et al., 2011).

Survey designA survey instrument was developed to test the two hypotheses. Thirteen items were used to measure the festival experience domains (5E's) that were derived from the literature review. Three items were used to measure the majority of the experience domains; three items for education (Lee, Lee, & Wicks, 2004; Manthiou et al., 2014; Mehmetoglu & Engen, 2011); three items for entertainment (Cole and Chancellor, 2009; Manthiou et al., 2014); three items for escapism (Manthiou et al., 2014; Park, Reisinger, & Kang, 2008); two items for esthetics (Gration, Arcodia, Raciti, & Stokes, 2011; Lee, Lee, Lee, & Babin, 2008); and two items for economic value (Yuan & Jang, 2008).

The construct memorable experience was measured using three items (Manthiou et al., 2014; Rubin & Kozin, 1984). Behavioral intentions included four items (Baker & Crompton, 2000). The first two items for behavioral intentions query Gen Y tourists’ intentions as to whether they will return to the destination without attending the festival, or return so they may attend the festival, or both. The last two items are related to word of mouth intentions toward Aruba and the festival. A 7-point Likert scale was used and anchored from 1 (Completely Disagree) to 7 (Completely Agree). The survey instrument also included various socio-demographic questions.

Data collectionData collection took place at key locations during the festival (e.g. near concession stands, resting areas, and exit areas). In order to ensure a proper sampling of Gen Y attendees, the survey was conducted on all days that the festival was in production. In order to capture Gen Y tourists, a purposive sampling technique was used. Purposive sampling permits the selection of suitable subjects (Gen Y) to answer the research questions that drive the current study (Mo, Havitz, & Howard, 1994). Because the study is interested in obtaining information from Gen Y festival attendees, purposive sampling was deemed the most appropriate technique to use.

A total of 325 surveys were collected during the music festival, 78 surveys on day one, 96 surveys on day two, and 150 surveys on day three. After deleting incomplete and unusable surveys, 288 surveys were used for the data analysis. The total amount of surveys collected represents approximately 16% of the total festival attendance.

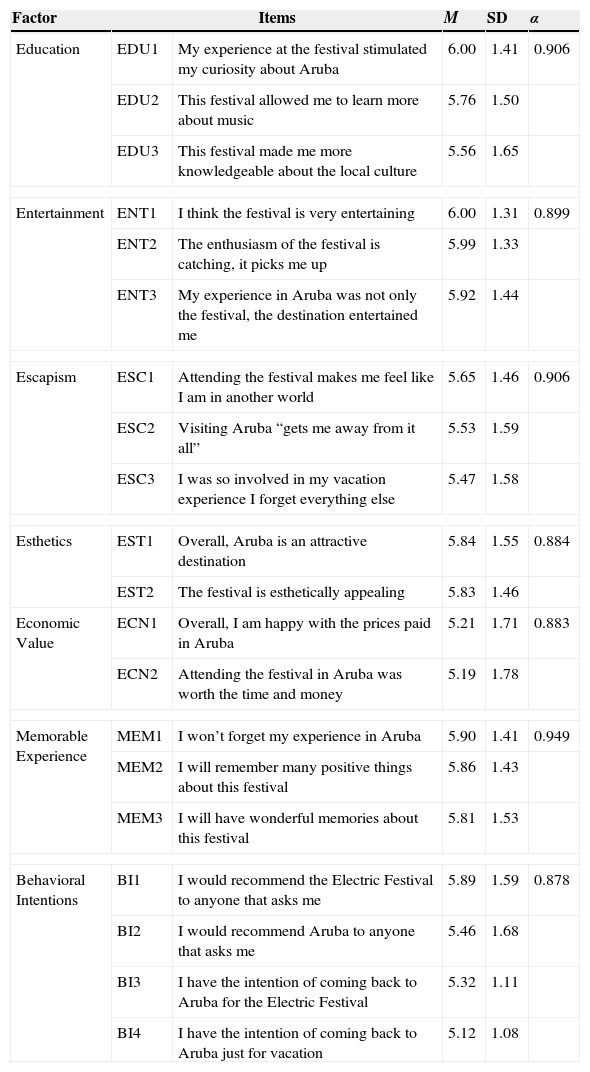

Measurement of variablesThe two hypotheses and the corresponding causal relationships among the latent variables were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM). The model was tested against the obtained measurement data to determine suitability. All the variables used in this study had a reliability coefficient that was higher than .88. The descriptive statistics for the variables are presented in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Factor | Items | M | SD | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | EDU1 | My experience at the festival stimulated my curiosity about Aruba | 6.00 | 1.41 | 0.906 |

| EDU2 | This festival allowed me to learn more about music | 5.76 | 1.50 | ||

| EDU3 | This festival made me more knowledgeable about the local culture | 5.56 | 1.65 | ||

| Entertainment | ENT1 | I think the festival is very entertaining | 6.00 | 1.31 | 0.899 |

| ENT2 | The enthusiasm of the festival is catching, it picks me up | 5.99 | 1.33 | ||

| ENT3 | My experience in Aruba was not only the festival, the destination entertained me | 5.92 | 1.44 | ||

| Escapism | ESC1 | Attending the festival makes me feel like I am in another world | 5.65 | 1.46 | 0.906 |

| ESC2 | Visiting Aruba “gets me away from it all” | 5.53 | 1.59 | ||

| ESC3 | I was so involved in my vacation experience I forget everything else | 5.47 | 1.58 | ||

| Esthetics | EST1 | Overall, Aruba is an attractive destination | 5.84 | 1.55 | 0.884 |

| EST2 | The festival is esthetically appealing | 5.83 | 1.46 | ||

| Economic Value | ECN1 | Overall, I am happy with the prices paid in Aruba | 5.21 | 1.71 | 0.883 |

| ECN2 | Attending the festival in Aruba was worth the time and money | 5.19 | 1.78 | ||

| Memorable Experience | MEM1 | I won’t forget my experience in Aruba | 5.90 | 1.41 | 0.949 |

| MEM2 | I will remember many positive things about this festival | 5.86 | 1.43 | ||

| MEM3 | I will have wonderful memories about this festival | 5.81 | 1.53 | ||

| Behavioral Intentions | BI1 | I would recommend the Electric Festival to anyone that asks me | 5.89 | 1.59 | 0.878 |

| BI2 | I would recommend Aruba to anyone that asks me | 5.46 | 1.68 | ||

| BI3 | I have the intention of coming back to Aruba for the Electric Festival | 5.32 | 1.11 | ||

| BI4 | I have the intention of coming back to Aruba just for vacation | 5.12 | 1.08 | ||

Overall, survey respondents entertain positive experiences in relation to each experiential domain. Items range from 5.12 to 6.00 out of a 7-point Likert scale. For example, survey respondents scored high on the entertainment domain: “I think the festival is very entertaining” (M=6.00); and, “The enthusiasm of the festival is catching” (M=6.99). Similarly, Aruba, as the host destination also impressed the respondents. For example, “Overall, Aruba is an attractive destination” (M=5.84); “The experience in Aruba was not only for the festival, the destination entertained me” (M=5.92); “I won’t forget my experience in Aruba” (M=5.90); and, “My experience at the festival stimulated my curiosity about Aruba” (M=6.00). Table 1 displays the results of the descriptive analysis. The results suggest that the festival provides a means to attract the Gen Y cohort to the SID.

Before testing the proposed hypotheses, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to determine which items were valid measures to capture the Gen Y attendees’ overall experience and future behavioral intentions. The CFA determines whether the number of factors and the loadings of measured variables on these factors conform to what is expected by pre-established theoretical framework. The Pine and Gilmore (1998) Experience Economy Model served as the pre-established framework. Indicator variables were selected on the basis of prior theory, and a factor analysis was used to examine whether the variables loaded on the expected number of factors (education, entertainment, escapism, esthetics, and economic value).

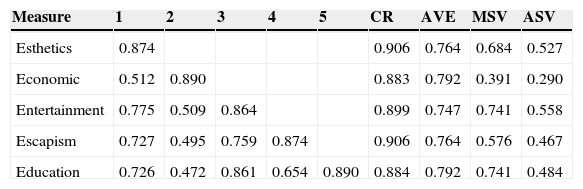

Scale validationA five-construct measurement model was evaluated using a CFA with the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method based on the model's goodness-of-fit indices, reliability, and the convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs. MLE was used because the assumption of multivariate normality was met. Therefore, MLE was considered an efficient and unbiased estimation method (Carmines & McIver, 1981). Each first-order latent construct had a set of variables as indicators and each of the observed variables were directly affected by a unique unobserved error. Errors were uncorrelated with other errors, and all of the errors were uncorrelated with the unobserved factors. All items significantly loaded on their specified latent construct and no undesirable cross-loadings emerged (see Table 2).

Correlations and squared correlations among the constructs and AVE.

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | CR | AVE | MSV | ASV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esthetics | 0.874 | 0.906 | 0.764 | 0.684 | 0.527 | ||||

| Economic | 0.512 | 0.890 | 0.883 | 0.792 | 0.391 | 0.290 | |||

| Entertainment | 0.775 | 0.509 | 0.864 | 0.899 | 0.747 | 0.741 | 0.558 | ||

| Escapism | 0.727 | 0.495 | 0.759 | 0.874 | 0.906 | 0.764 | 0.576 | 0.467 | |

| Education | 0.726 | 0.472 | 0.861 | 0.654 | 0.890 | 0.884 | 0.792 | 0.741 | 0.484 |

Note: Diagonal figures indicate the root square of AVE.

The acceptable fit indices for a model require that the normed fit index (NFI) and comparative fit index (CFI) values are greater than or equal to .90. The acceptable range for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is .05 to .08 (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010). For the complete sample, the overall goodness-of-fit indices showed that the five-construct model had an acceptable fit with the data (X2(147)=392.492, p<.001, CFI=.954, NFI=.929; RMSEA=.07). Better-fitting models are said to have a X2:df ratio on the order of 3:1 or less (Hair et al., 2010). Therefore, based on X2:df ratio of 2.67, the researchers concluded that there are intercorrelations among the festival experiential domains across the subscales employed in the measurement of the five “E's”.

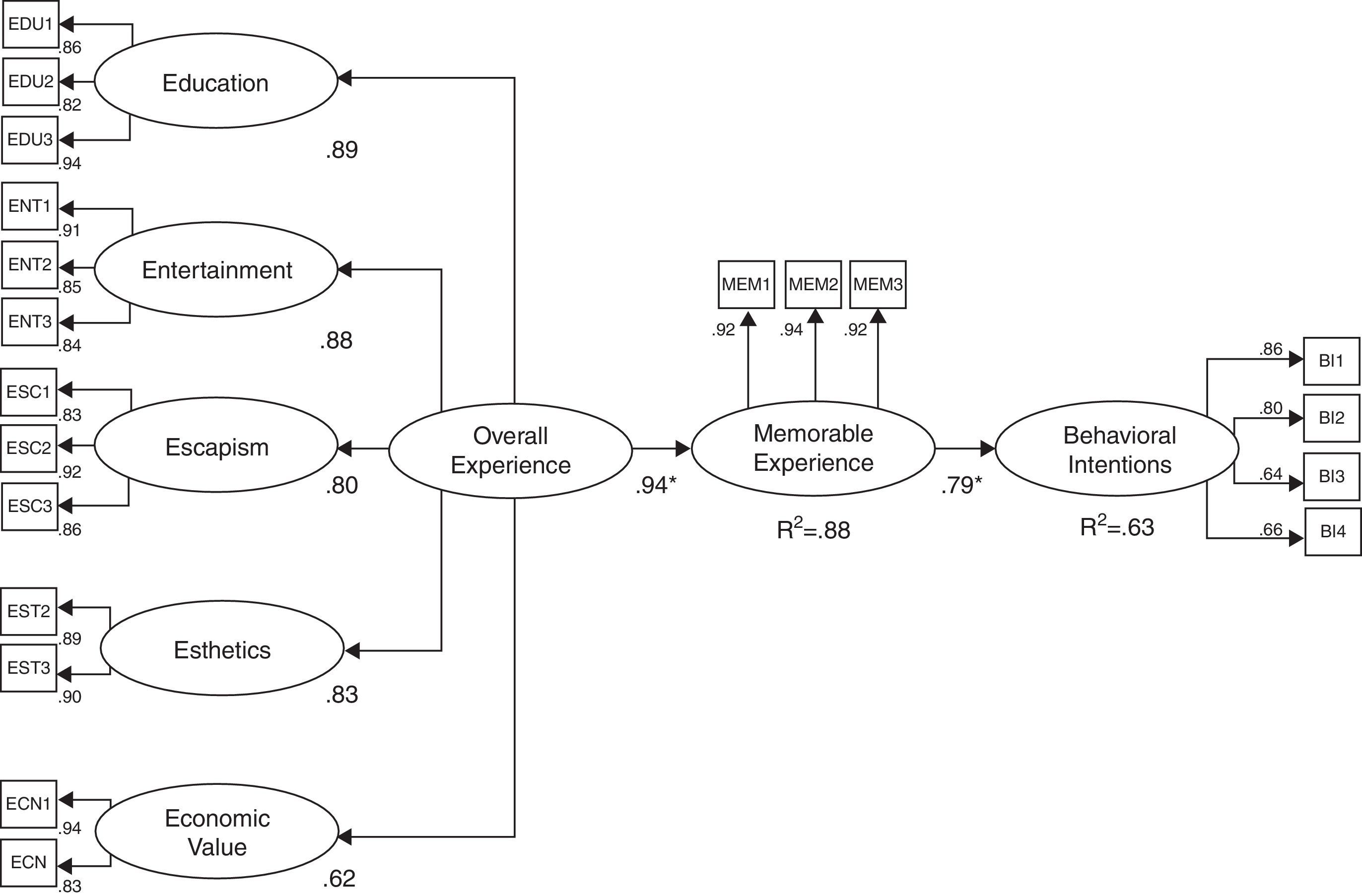

The structural equation model: the festival experience in the context of Gen YIn order to measure the effects of the festival experience, the study considered a second-order CFA, i.e., the “overall experience”. The study assumed that although the five domains of the festival experience are distinct from each other, they are related constructs, which may be accounted for by one common underlying higher-order construct. The festival experience was a second-order latent factor composed of the five first-order constructs: education, entertainment, escapism, esthetics, and economic value. A higher-order factor analysis was used to test the hypothesized model for the festival experience on memorable experience and behavioral intentions of the Gen Y cohort.

In order to determine whether the model accounts for the relationships among the constructs, the first-order latent factors were correlated during the first-order factor analysis. Each relationship was estimated directly in a construct covariance/correlation matrix (Hair et al., 2010). Single-headed arrows lead from the second-order factor (overall experience) to each of the first-order factors. These regression paths represent first-order factor loadings. Empirically, the higher-order factors may be thought of as a way of accounting for the covariance between constructs (Hair et al., 2010).

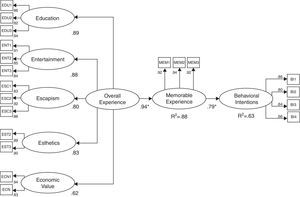

Each of the first-order constructs significantly contributed to the account of the second-order construct of overall experience as follows: education, (β=.87, p<.001), entertainment (β=.89, p<.001), escapism (β=.84, p<.001), esthetics (β=.82, p<.001), and economic value (β=.58, p<.001). Again, the overall goodness-of-fit indices showed that the five-construct model had an acceptable fit with the data (X2(97)=58, p<.001, CFI=.969, NFI=.969; RMSEA=.048).

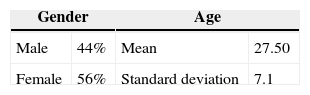

ResultsSample profileTable 3 represents the demographic information regarding the sample. The majority of the attendees participated in the festival for at least two days. The gender distribution of the attendees indicates that 56 percent of the respondents were female and 44 percent of the respondents were male. The majority of the respondents visited from Venezuela (34%), the United States (21%), and the Netherlands (15%). With regard to marital status, 82 percent of the respondents were single.

Demographic information.

| Gender | Age | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 44% | Mean | 27.50 |

| Female | 56% | Standard deviation | 7.1 |

| Country | Income | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Venezuela | 34% | Under US$25,000 | 30% |

| United States | 21% | US$25,000–US$29,999 | 8% |

| Netherlands | 15% | US$30,000–US$39,999 | 16% |

| Curacao | 9% | US$40,000–US$49,999 | 13% |

| Brazil | 5% | US$50,000–US$74,999 | 13% |

| Colombia | 5% | US$75,000–US$99,999 | 10% |

| Other | 11% | US$100,000 and over | 10% |

| Education | Days attending the festival | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High school | 26% | 1 day | 24% |

| Undergraduate degree | 54% | 2 days | 27% |

| Master or doctorate | 20% | 3 days | 49% |

| Place of stay | Purpose of visit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hotel | 62% | The Electric Festival | 58% |

| Apartment | 16% | Sun and beach tourism | 30% |

| Family & Friends | 13% | Business/conference | 4% |

| Guest House/Small Hotel | 6% | Shopping | 4% |

| Other | 3% | Visit family and friends | 4% |

| Marital status | Previous visit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | 82% | Yes | 40% |

| Married | 18% | No | 60% |

In terms of education, 26 percent of the respondents had a high school diploma, and 76 percent of the respondents had a higher education degree (54% with a bachelor's degree and 20% with a graduate degree). The majority of the Gen Y respondents (60%) were visiting Aruba for the first time. A little more than half of the respondents (54%) had incomes lower than US$40,000. The average age of the respondents was 27.5 years (SD=7.1). This age is representative of the Gen Y cohort. As for the motivation to visit Aruba, more than half of the respondents (58%) indicated that the festival was their main motivator to travel.

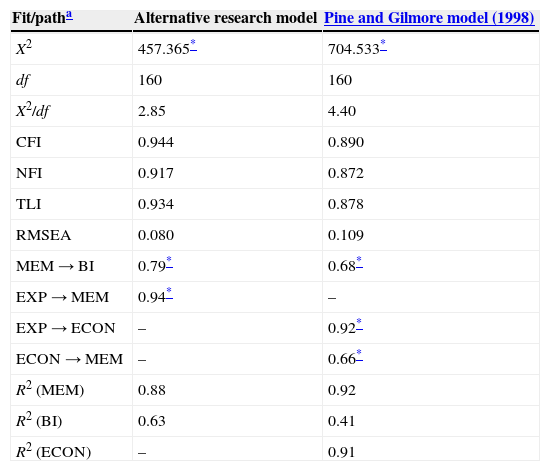

Structural equation model (SEM)The purpose of SEM is to test conceptual and theoretical models. Therefore, the original experience economy framework proposed by Pine and Gilmore (1998) was tested within the context of the current study. Based on literature pertaining to the Gen Y cohort and the investment required to travel to a SID, an alternative model is proposed and tested as a comparative means to that of the original framework. The alternative model embeds economic value as part of the overall experience. Thus, the alternative model moves from the traditional 4E model to that of a 5E model. For comparison purposes, distinctive fit indices are reported as suggested by Cronin et al. (2000). The results are presented in Table 4.

Results of model comparison.

| Fit/patha | Alternative research model | Pine and Gilmore model (1998) |

|---|---|---|

| X2 | 457.365* | 704.533* |

| df | 160 | 160 |

| X2/df | 2.85 | 4.40 |

| CFI | 0.944 | 0.890 |

| NFI | 0.917 | 0.872 |

| TLI | 0.934 | 0.878 |

| RMSEA | 0.080 | 0.109 |

| MEM→BI | 0.79* | 0.68* |

| EXP→MEM | 0.94* | – |

| EXP→ECON | – | 0.92* |

| ECON→MEM | – | 0.66* |

| R2 (MEM) | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| R2 (BI) | 0.63 | 0.41 |

| R2 (ECON) | – | 0.91 |

Following Hu and Bentler's (1999) recommendations, the researchers compared the absolute fit indices (X2), the relative fit indices (Normed Fit Index and the Tucker Lewis Index), and non-centrality based indices (Steiger-Lind root mean square error, Bentler comparative fit index). When comparing the two model's recommended absolute fit indices, the alternative model demonstrates a superior fit according to the X2:df ratio (2.85 vs. 4.40). In addition, the ability of the proposed research model to explain Gen Y music festivals behavioral intentions (using R2 values) in the context of a SID is a better fit to that of the Pine and Gilmore model.

A closer look at the relative fit indices indicate that when comparing the chi square for the research model versus the corresponding Pine and Gilmore baseline model, the alternative model's TLI and NFI have values above .90. Thus, the alternative research model is considered a good fitting model (Hair et al., 2010). The RMSEA and CFI fit measures are also higher and exceed the recommended threshold for a good fit. Based on such evidence, the proceeding discussion about the effect of the overall experience at a music festival on behavioral intentions will be restricted to the proposed alternative research model.

The parameter estimates of the structural model for the effects of festival experience on behavioral intention for Gen Y are presented in Fig. 3. The results of the structural equation model show an acceptable fit for the model (X2(160)=457.365, p<.001, CFI=.944, NFI=.917; RMSEA=.080). The results support Hypothesis 1. The path from overall experience shows a positive and strong direct relationship with memorable experience (γ=.94, p<.001). The overall experience domain explains 88 percent of the variance for the construct memorable experience.

The second hypothesis predicted that memorable experiences had a positive effect on behavioral intentions. The results show that a direct effect between memorable experiences and behavioral intentions was statistically significant (γ=.79, p<.001). The memorable experience dimensions explained 63 percent of the variance for the behavioral intentions. In addition, after accounting for all of the simultaneity in the model, the total effect of the festival experience on behavioral intention is .742. The total effects of the second-order factor (overall experience) 5E's are closely related to behavioral intentions.

The causal relationship revealed in Fig. 3 indicates that the experience enjoyed by Gen Y tourists during their visit (attending the festival as well as roaming the island destination) has set an excited perception about the destination. The memorable experience has triggered a strong behavioral intention to return to and recommend the destination and the festival to others. In other words, the experience at the festival spawns a highly significant opportunity for Aruba, as a SID, to make contact with the Gen Y cohort, and to welcome these festival attendees back to Aruba.

ConclusionThis study had a threefold purpose. First, to test the experience economy framework in the context of a SID in order to determine if a music festival may be used as an experiential product to attract a new cohort to a destination. Second, to examine a music festival's experiential domains that may influence the overall experience of Gen Y tourists. And, third to determine if the overall experience of Gen Y tourists who attend a music festival may predict their behavioral intentions to return to and recommend a SID.

Substantial research has been dedicated to investigate the baby boomer cohort's needs and preferential desires for travel related purchases (Patterson, 2006; Patterson & Pegg, 2009). Based on this line of research, destinations have configured tourism product portfolios that align with this cohort's needs and wants. However, as cohort replacement theory predicts, it is a natural social progression for an older predominant generation to be replaced by younger birth cohorts (Li et al., 2013). Therefore, from a tourism development perspective, this may create some issues for economies, like that of SIDs, that depend upon the tourism industry as an economic driver for other industry sectors’ performance.

An impending need is approaching for DMOs located in SIDs to identify the next generational succession, thus providing rationale for this study. Gen Y has seemingly emerged as the newest forming cohort that may offer an equal or more potent economic impact in the travel industry to that of other generations (Noble, Haytko, & Phillips, 2009). Destinations that are able to penetrate this market may influence a relatively young cohort that is first developing travel tastes and preferences. Accessing this market segment may provide destinations a competitive advantage in the acquisition of future tourist market share.

Due to the global entrance of the experience economy (Pine & Gilmore, 1998), most tourism product portfolios follow modern product development schemas where the majority of tourism escapism, esthetics, and economic value might provide a better conceptual fit to explain the products that represent experiential products. Therefore, the study adopted the experience economy framework of Pine and Gilmore (1998). Under this context, a music festival was examined as an experiential product that could attract the Gen Y market segment to a SID without disrupting the current product portfolio that is geared toward satisfying the baby boomer generation.

The traditional experience economy framework references a first-order structural equation model that includes 4E's (education, entertainment, escapism, and esthetics). Based on Gen Y literature and the investments required to access a SID for tourists, the current study found that an alternative second order model that includes 5E's better explains behavioral intentions of the Gen Y cohort. The inclusion of economic value (5th E) that emerged as a domain to consider in the overall experience for the Gen Y cohort seems relevant in the circumstantial context of traveling to a SID. This finding is based on the progression of economic value that assumes that the consumption of the core experience (music festival) is contingent upon the timely consumption of supporting products required to satisfy the overall experience.

In other words, the music festival is a time sensitive product that may only be consumed during a specific time horizon; yet, in order to consume the core experience it requires tourists/attendees to purchase supporting products within the same time period. This process deviates from the normal consumption pattern of other travel experiences where tourists typically have the discretion of choice regarding when they would like to travel. Thus, the major theoretical contribution is that for the Gen Y cohort, economic value seems embedded in the overall experience rather than serving as a mediating variable to predict future intentions.

Although the original framework of Pine and Gilmore references the use of economic value as a variable to consider in predicting behavioral intentions, the model does not include economic value as a variable that influences the overall experience. Therefore, the original framework only partially explains the behavior of the Gen Y cohort in the context of a SID. The current study deviates from mainstream festival experience literature in that economic value is an important consideration for Gen Y tourists to recommend and revisit a SID. The inclusion of economic value as part of the second-order construct for overall experience provides a practical measurement framework for potential Gen Y tourists. This is a major implication for this study.

Additionally, the results suggest that the production of a music festival that creates a memorable experience in a SID provides a means for industry practitioners to penetrate a new market that seems willing to return and recommend the SID as a vacation site even in the absence of the festival. This information may provide market penetration and development contingencies for SIDs that desire to attract a new generation. However, it is important to note that if the tactic of using music festivals as experiential products was adopted, then the overall affect may depend upon the saliency of the other tourism experiential offerings available at the destination.

External generalizability is a notable limitation for this study. Future research should extend the sampling to include more music festivals that occur in other SIDs then Aruba. Additionally, the genre of music that is represented at a music festival should be considered in future research studies (Bowen & Daniels, 2005). The current study used an electric music festival that occurred in a SID to access a broad majority of Gen Y tourists visiting a SID. It is possible that this genre of music represents a crowd that places more emphasis on economic value than Gen Y tourists who attend other types of music festivals. Overall, it is also possible that the extension of sampling within different contexts may also introduce variations to the experience economy framework.

The findings provide interesting results that contribute to advancing the experience economy framework in the context of cohort replacement. This provides meaningful insight to industry practitioners looking for a means to secure market share with the next generation succession without displacing a predominant cohort. The research provides a platform for researchers to consider the reorganization of the traditional experience economy. Since the current research only examines usage and post-consumption behavior, it may behoove future researchers to examine antecedents of the experience (e.g. motives) and other post-purchase behaviors in varying units of analysis (e.g. electronic word-of-mouth) (Litvin, Goldsmith, & Pan, 2008).

Last, it is important for future research to acknowledge that there is an emerging debate in broad discipline marketing research regarding the use of reflective versus formative models (Jarvis, Mackenzie, & Podsakaoff, 2003). Based on tourism literature the current study adopted a reflective model of the Pine and Gilmore experience economy framework (Ali, Hussain, & Ragavan, 2014; Cole & Chancellor, 2009; Oh et al., 2007; Song, Lee, Park, Hwang, & Reisinger, 2014). This means that causality assumes the direction from the latent construct to the items measured. To the contrary, formative models suggest that the variation in the latent construct does not cause variation in the items measured. The decision making rules of thumb that dictate a researcher's choice of reflective versus formative models have not been widely applied in tourism research. Future research should investigate the ontological disposition of SEM models that test the experience economy framework in the context of unique tourism applications like that of cohort replacement in varying market conditions (e.g. SIDs).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.