Gender violence is a major public health problem with a significant socio-family and economic impact. The aim of this study was to analyse the characteristics and circumstances of abuse, including the subjects involved (victim and aggressor), their intimate relationship, as well as the peculiarities of abuse and its harmful consequences.

Material and methodsRetrospective and descriptive study of cases classified as gender violence from the prosecutor's office of Santiago de Compostela between 2005 and 2012. A total of 398 cases of gender violence with a final conviction were analysed.

ResultsVictims were mainly young women (mean age 36.6 years), of Spanish nationality (82.91%), married (39.70%), with children (69.85%), employed (40.45%) and with low socioeconomic status (53.52%). Aggressors had an average age of 39.5 years, were predominantly Spanish (85.93%) and of low socioeconomic status (37.44%). At the time of abuse, 56.03% of the couples lived together and 62.22% shared the house with children. The maltreatment, mainly a combination of physical and psychological abuse (43.72%), occurred most often at home (65.08%) and was witnessed by others (64.57%). As a result of the aggression, 53.02% of women suffered physical injuries, generally bruises or haematomas (41.21%) located mainly on the upper limbs (26.88%) and face (24.37%).

ConclusionsThe information obtained on the characteristics and circumstances of abuse is an essential step in order to formulate evidence-based intervention and treatment strategies.

La violencia de género constituye un importante problema de salud pública con un gran impacto sociofamiliar y económico. El objetivo de este estudio ha sido analizar las características y circunstancias del maltrato, incluyendo a los sujetos implicados (víctima y agresor) y su relación de pareja, así como las peculiaridades del abuso y sus consecuencias lesivas.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo, de tipo descriptivo, de los casos clasificados como violencia de género por la Fiscalía de Área de Santiago de Compostela, durante el período 2005-2012. Se analizaron 398 casos de violencia de género con sentencia firme condenatoria.

ResultadosLas víctimas eran, sobre todo, mujeres jóvenes (media 36,6 años), de nacionalidad española (82,91%), casadas (39,70%), con hijos (69,85%), empleo remunerado (40,45%) y nivel socioeconómico bajo (53,52%). Los agresores tenían una edad media de 39,5 años, con predominio de españoles (85,93%), de nivel socioeconómico bajo (37,44%). En el momento de la agresión, el 56,03% de las parejas convivían y un 62,22% compartía la vivienda con los hijos. El maltrato, fundamentalmente combinación de abuso físico y psicológico (43,72%), se produjo sobre todo en el domicilio (65,08%) y fue presenciado por terceras personas (64,57%). Como consecuencia de la agresión, el 53,02% de las mujeres sufrieron lesiones físicas, básicamente contusiones o hematomas (41,21%), localizadas principalmente en los miembros superiores (26,88%) y en la cara (24,37%).

ConclusionesLa información obtenida sobre las características y circunstancias del maltrato es fundamental para adaptar, en base a la evidencia, las medidas de intervención y tratamiento de este problema.

Gender violence is a major public health problem that is a serious violation of human rights, with repercussions in the socio-family, economic and legal spheres.1 Although its incidence is difficult to determine, the World Health Organisation estimates that it will affect one-third of women at some point in their lives.2 Moreover, the V macro-survey on violence against women carried out in our country, estimates that 12.5% of Spanish women have at some time been abused by their partner.3

It is a universal and complex problem that must be analysed from a multidimensional perspective since there is no single causal agent but is determined by various individual, relational, community and social factors that interact by favouring violence or protecting against it.4 The individual factors which increase the probability of being a victim or aggressor include younger age, low level of education and unemployment.5 Regarding the environment and the relationship, risk factors include cohabitation and being a large family.6,7 Finally, it is worth emphasising sociocultural factors such as low economic status5 or immigration,8 which increase the vulnerability of women, since they involve the accumulation of various factors, such as more precarious work or difficulties accessing support resources. On the other hand, it is considered that if the woman has social support or has a high educational level, these are protective factors against this type of violence.9

Abuse has been shown to have negative health consequences, both in the short and long term. The most visible and direct effects are physical injuries, which affect half the victims10 and for which about 30% require medical care.11 They may suffer superficial injuries, such as bruises or abrasions, or injuries from various types of weapons, burns or intoxications with criminal purposes.12 It has been described that the most common locations are the head, neck and face.13 The injuries associated with abuse are important both from a health and criminological perspective. A thorough evaluation and documentation of these are essential since they can play a fundamental role in different moments of the judicial process.

In recent years, different research projects have been undertaken that try to increase the knowledge of the problem and the factors involved, with the purpose of improving the prevention, treatment and rehabilitation measures for those involved. Most of these studies have been done from the health field, mainly through surveys. Those that approach the subject from the judicial perspective are more limited, although the data obtained from judicial proceedings are an important source of information that allows us to approach this problem from an objective perspective, based on facts proven by the judge.

The objective of this study was to improve the knowledge of gender violence from a medico-legal and criminological perspective based on cases with a final conviction. The specific objectives were to analyse the characteristics of the subjects involved (victim and aggressor), their context and circumstances, the peculiarities of the abuse and its harmful consequences.

Materials and methodsA retrospective study of the cases classified as gender violence by the Area Prosecutor of Santiago de Compostela was conducted from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2012. Only those cases with a final conviction were included, excluding those that were pending judgement and those that concluded with the acquittal of the accused or due to other causes.

This research was conducted as part of an agreement between the Prosecutor's Office of the Autonomous Community of Galicia and the Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. During this research, the ethical norms for the collection of personal data were fulfilled, with the rights to privacy and confidentiality being protected. These were treated as dissociated information that prevented the identification of those involved and the entire research staff kept the relevant confidentiality commitment.

The information on each case was collected in a set of previously designed records, gathering the relevant data from the different documents included in the files of the Prosecutor's Office, reviewing the police records, the fiscal reports and the medical-legal documents (parts of injuries, expert reports and other medical reports). In addition to the judicial decision, the following data were collected:

- -

Socio-demographic data of the victim and the aggressor: age, marital status, country of origin, level of education, employment status, socio-economic level, regular consumption of substances and number of children.

- -

Context and relationship data: duration of the relationship, members of the family unit, cohabitation or not at the time of the events and ownership of the family home.

- -

Data related to the abuse and its circumstances: type and mechanisms of abuse, duration of abuse, place of occurrence, presence of third parties, consumption of substances at the time of the events by the victim and the aggressor.

- -

Information regarding the injuries: presence or not of physical injuries, number, type and location.

All of these data were included in a digital database (Microsoft Office Excel 2007®) and then a descriptive statistical analysis was performed using the R programme (Brian Ripley, 2014: version 1.0-35). The mean and standard deviation were calculated for quantitative variables and percentages for qualitative variables.

ResultsBetween the years 2005–2012, 580 cases were classified as gender violence in the Santiago de Compostela Prosecutor's Office. In 68.6% of the cases, the events were proved and the accused was found guilty. This study focuses on those 398 cases of gender violence confirmed by judicial decision.

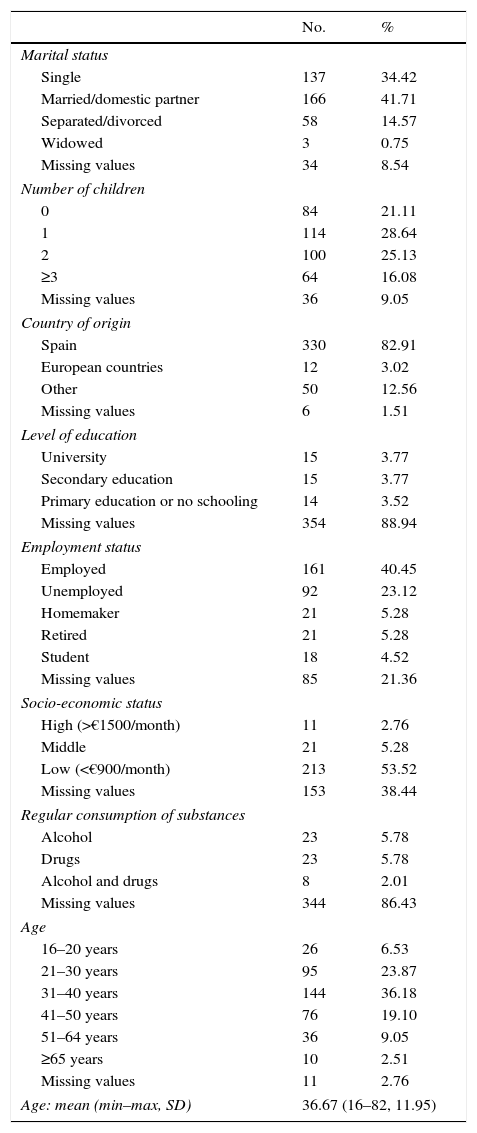

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the victims. The age of the women was between 16 and 80 years, with about 80% between 21 and 50 years. A clear predominance of women of Spanish nationality with children and low socio-economic level was observed. The numbers of married women with paid employment are also higher, but with smaller differences in relation to other marital or employment statuses, respectively. In spite of the high number of missing values in this variable, we have recorded that 14% of the women regularly consumed some type of substance (alcohol or illegal drugs).

Socio-demographic characteristics of the victims (No.=398).

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 137 | 34.42 |

| Married/domestic partner | 166 | 41.71 |

| Separated/divorced | 58 | 14.57 |

| Widowed | 3 | 0.75 |

| Missing values | 34 | 8.54 |

| Number of children | ||

| 0 | 84 | 21.11 |

| 1 | 114 | 28.64 |

| 2 | 100 | 25.13 |

| ≥3 | 64 | 16.08 |

| Missing values | 36 | 9.05 |

| Country of origin | ||

| Spain | 330 | 82.91 |

| European countries | 12 | 3.02 |

| Other | 50 | 12.56 |

| Missing values | 6 | 1.51 |

| Level of education | ||

| University | 15 | 3.77 |

| Secondary education | 15 | 3.77 |

| Primary education or no schooling | 14 | 3.52 |

| Missing values | 354 | 88.94 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 161 | 40.45 |

| Unemployed | 92 | 23.12 |

| Homemaker | 21 | 5.28 |

| Retired | 21 | 5.28 |

| Student | 18 | 4.52 |

| Missing values | 85 | 21.36 |

| Socio-economic status | ||

| High (>€1500/month) | 11 | 2.76 |

| Middle | 21 | 5.28 |

| Low (<€900/month) | 213 | 53.52 |

| Missing values | 153 | 38.44 |

| Regular consumption of substances | ||

| Alcohol | 23 | 5.78 |

| Drugs | 23 | 5.78 |

| Alcohol and drugs | 8 | 2.01 |

| Missing values | 344 | 86.43 |

| Age | ||

| 16–20 years | 26 | 6.53 |

| 21–30 years | 95 | 23.87 |

| 31–40 years | 144 | 36.18 |

| 41–50 years | 76 | 19.10 |

| 51–64 years | 36 | 9.05 |

| ≥65 years | 10 | 2.51 |

| Missing values | 11 | 2.76 |

| Age: mean (min–max, SD) | 36.67 (16–82, 11.95) | |

SD: standard deviation.

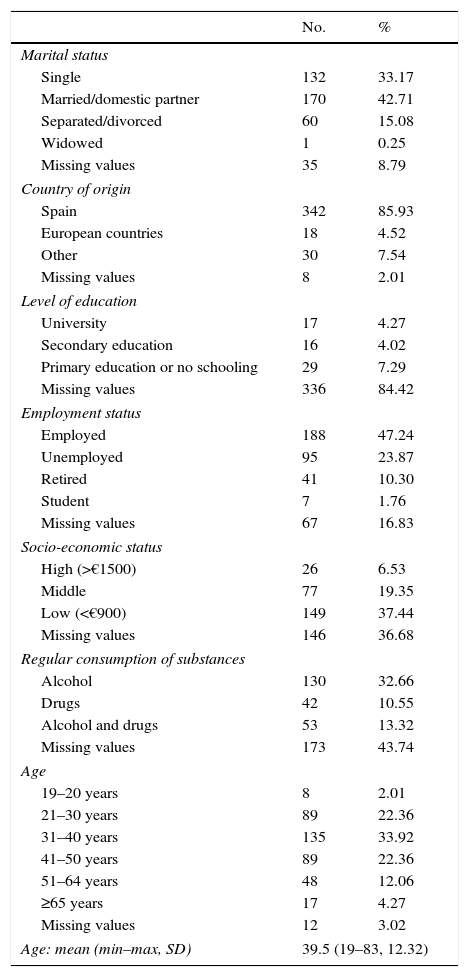

As can be seen in Table 2, 78.64% of the aggressors were between 21 and 50 years old. Most were men of Spanish nationality, married, with paid employment and low socio-economic level. 56.53% regularly consumed some type of substance.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the aggressors (No.=398).

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 132 | 33.17 |

| Married/domestic partner | 170 | 42.71 |

| Separated/divorced | 60 | 15.08 |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.25 |

| Missing values | 35 | 8.79 |

| Country of origin | ||

| Spain | 342 | 85.93 |

| European countries | 18 | 4.52 |

| Other | 30 | 7.54 |

| Missing values | 8 | 2.01 |

| Level of education | ||

| University | 17 | 4.27 |

| Secondary education | 16 | 4.02 |

| Primary education or no schooling | 29 | 7.29 |

| Missing values | 336 | 84.42 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 188 | 47.24 |

| Unemployed | 95 | 23.87 |

| Retired | 41 | 10.30 |

| Student | 7 | 1.76 |

| Missing values | 67 | 16.83 |

| Socio-economic status | ||

| High (>€1500) | 26 | 6.53 |

| Middle | 77 | 19.35 |

| Low (<€900) | 149 | 37.44 |

| Missing values | 146 | 36.68 |

| Regular consumption of substances | ||

| Alcohol | 130 | 32.66 |

| Drugs | 42 | 10.55 |

| Alcohol and drugs | 53 | 13.32 |

| Missing values | 173 | 43.74 |

| Age | ||

| 19–20 years | 8 | 2.01 |

| 21–30 years | 89 | 22.36 |

| 31–40 years | 135 | 33.92 |

| 41–50 years | 89 | 22.36 |

| 51–64 years | 48 | 12.06 |

| ≥65 years | 17 | 4.27 |

| Missing values | 12 | 3.02 |

| Age: mean (min–max, SD) | 39.5 (19–83, 12.32) | |

SD: standard deviation.

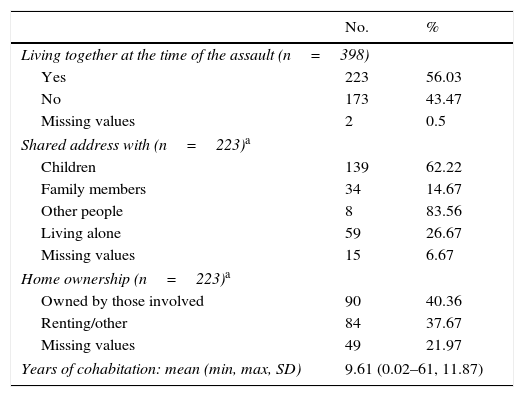

In 56% of the cases, the couple lived together at the time of the assault, usually in a flat which they owned. In 62.2%, the couple shared the home with children and, to a lesser extent, with other people (Table 3).

Characteristics of the relationship.

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Living together at the time of the assault (n=398) | ||

| Yes | 223 | 56.03 |

| No | 173 | 43.47 |

| Missing values | 2 | 0.5 |

| Shared address with (n=223)a | ||

| Children | 139 | 62.22 |

| Family members | 34 | 14.67 |

| Other people | 8 | 83.56 |

| Living alone | 59 | 26.67 |

| Missing values | 15 | 6.67 |

| Home ownership (n=223)a | ||

| Owned by those involved | 90 | 40.36 |

| Renting/other | 84 | 37.67 |

| Missing values | 49 | 21.97 |

| Years of cohabitation: mean (min, max, SD) | 9.61 (0.02–61, 11.87) | |

SD: standard deviation.

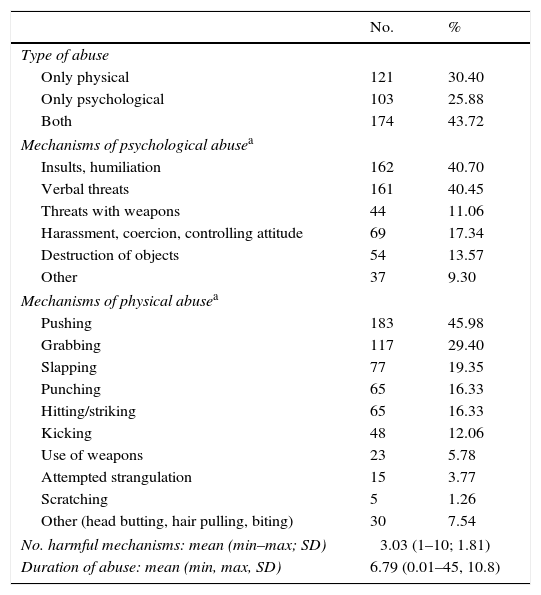

The characteristics of abuse are described in Table 4. The combination of physical and psychological abuse was the most common form. With regard to physical assaults, the most common mechanism was pushing and, to a lesser extent, grabbing or slapping the woman. The main mechanisms of psychological abuse were to insult, humiliate or make false accusations and verbal threats. The woman was frequently the victim of multiple harmful mechanisms. The mean duration of the abuse was longer than 6 years.

Characteristics of the abuse (No.=398).

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of abuse | ||

| Only physical | 121 | 30.40 |

| Only psychological | 103 | 25.88 |

| Both | 174 | 43.72 |

| Mechanisms of psychological abusea | ||

| Insults, humiliation | 162 | 40.70 |

| Verbal threats | 161 | 40.45 |

| Threats with weapons | 44 | 11.06 |

| Harassment, coercion, controlling attitude | 69 | 17.34 |

| Destruction of objects | 54 | 13.57 |

| Other | 37 | 9.30 |

| Mechanisms of physical abusea | ||

| Pushing | 183 | 45.98 |

| Grabbing | 117 | 29.40 |

| Slapping | 77 | 19.35 |

| Punching | 65 | 16.33 |

| Hitting/striking | 65 | 16.33 |

| Kicking | 48 | 12.06 |

| Use of weapons | 23 | 5.78 |

| Attempted strangulation | 15 | 3.77 |

| Scratching | 5 | 1.26 |

| Other (head butting, hair pulling, biting) | 30 | 7.54 |

| No. harmful mechanisms: mean (min–max; SD) | 3.03 (1–10; 1.81) | |

| Duration of abuse: mean (min, max, SD) | 6.79 (0.01–45, 10.8) | |

SD: standard deviation.

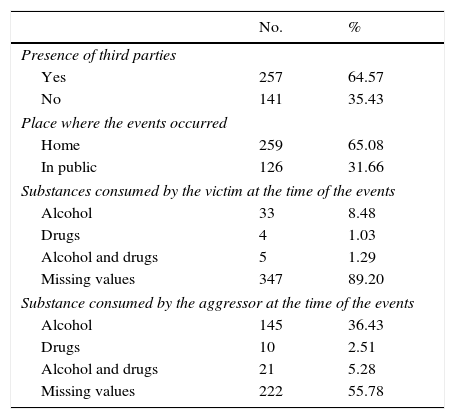

As shown in Table 5, the assaults usually occurred at home and were witnessed by third parties. At the time of the abuse, 10.08% of women and 44.22% of men were under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

Circumstances of the abuse (No.=398).

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of third parties | ||

| Yes | 257 | 64.57 |

| No | 141 | 35.43 |

| Place where the events occurred | ||

| Home | 259 | 65.08 |

| In public | 126 | 31.66 |

| Substances consumed by the victim at the time of the events | ||

| Alcohol | 33 | 8.48 |

| Drugs | 4 | 1.03 |

| Alcohol and drugs | 5 | 1.29 |

| Missing values | 347 | 89.20 |

| Substance consumed by the aggressor at the time of the events | ||

| Alcohol | 145 | 36.43 |

| Drugs | 10 | 2.51 |

| Alcohol and drugs | 21 | 5.28 |

| Missing values | 222 | 55.78 |

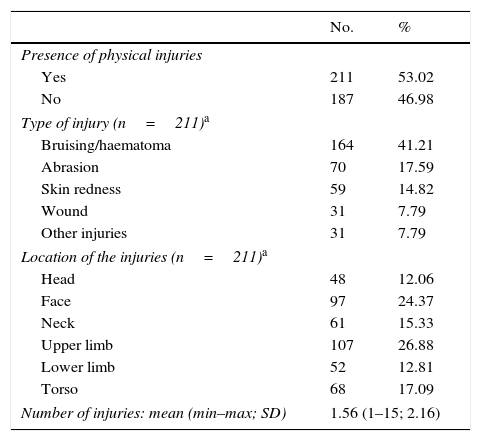

More than half of the women suffered physical injuries as a result of the abuse and often had more than one injury. The most common types were bruises or haematomas and abrasions. 7.79% had more serious injuries, such as sprains or fractures. As for the location, they were mainly found in the upper limbs and in the face (Table 6).

Characteristics of the injuries (No.=398).

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of physical injuries | ||

| Yes | 211 | 53.02 |

| No | 187 | 46.98 |

| Type of injury (n=211)a | ||

| Bruising/haematoma | 164 | 41.21 |

| Abrasion | 70 | 17.59 |

| Skin redness | 59 | 14.82 |

| Wound | 31 | 7.79 |

| Other injuries | 31 | 7.79 |

| Location of the injuries (n=211)a | ||

| Head | 48 | 12.06 |

| Face | 97 | 24.37 |

| Neck | 61 | 15.33 |

| Upper limb | 107 | 26.88 |

| Lower limb | 52 | 12.81 |

| Torso | 68 | 17.09 |

| Number of injuries: mean (min–max; SD) | 1.56 (1–15; 2.16) | |

SD: standard deviation.

Between the years 2005 and 2012, in nearly 7 of every 10 cases of gender violence in the Santiago de Compostela Prosecutor's Office, the judicial decision was condemnatory. They included 398 cases that involved mainly young couples with a long-term relationship. The majority lived together at the time of the events so it is not surprising that the abuse (physical and psychological) mainly occurred in the privacy of the family, i.e. in the home that they both shared, and lasted for years.

The literature on the subject emphasises that partner violence is a universal and cross-sectional problem that affects all segments of society, although it also emphasises that there are a number of factors that increase victimisation. Gender violence is considered to be more common in young couples and its prevalence decreases as age increases.14 In our study, although the age range of both the victims and the aggressors was broad, the average was in the thirties, which is consistent with other publications.1,6,15,16

As regards marital status, the literature is contradictory. Although formal marriage is considered primarily a protective factor and being single, separated or divorced has been described as a risk factor,17 there are also studies that indicate that being married is a risk factor that predicts greater victimisation14 and series with significant percentages of married women.4,9 In our sample, women and married men predominated, although there was also a significant number of single people. This seems to indicate that marital status or formalisation of the relationship is not a determining factor.

On the other hand, it has been described that unemployment is a risk factor for gender violence.8 In contrast, in our study, most of the victims and aggressors had paid employment. Although, it must be highlighted that in the case of women, the group of unemployed women, housewives and students was a considerable number. However, in the case of abusers, the percentage of individuals with a job was almost double the percentage of those unemployed. Nevertheless, socio-economic status was low in a large number of cases, which is in line with the literature.6,8

The risk of being a victim of partner violence has also been associated with immigration, which is considered a situation of special vulnerability14,18,19 due to the accumulation of various risk factors, such as ignorance of the language, precarious work and difficulties in accessing support systems or health services. In addition to increasing the probability of being abused, immigration is related to a higher mortality rate.4,18,20 Sanz-Barbero et al.20 consider that the risk of immigrant women exposed to gender violence being killed is five times higher than that of Spanish women. In our study, the majority of those involved, both women and men, were of Spanish nationality. However, the percentage of those from other countries (15.6% and 12%, respectively) is significant considering that in 2011, the percentage of foreign women and men residing in Galicia was approximately 4%.21 Knowledge of the characteristics of the abused population in a specific place allows the resources to be reorganised and results to be improved.

Moreover, as reflected in different studies, consumption, especially of alcohol, is one of the main risk factors for partner violence.22,23 In our series we considered, on the one hand, whether the victim or the aggressor consumed a substance on a regular basis and, on the other hand, if either of the two was under the effects of these substances at the time of the events. This is of special importance since it is considered that alcohol is the main substance that acts in the aggressor as a remover of inhibitions23 and in the victim reduces the ability to protect themselves or avoid a violent situation.24 Although we lacked this information in a significant number of cases, we found that at least about 14% of women were habitual users of substances and 10% were under the effects of alcohol or drugs at the time of the events. Consumption by the aggressor was higher; 1/3 consumed alcohol on a regular basis and 10.5% illegal drugs, although 13.3% were users of multiple substances. In 44.22% of cases, the aggressor was under the effects of some substance when he attacked his partner. These data indicate the need to take this factor into account in the analysis of the cases and raise the importance of the implementation of campaigns to prevent alcohol and drug consumption.

The data related to the relationship and family context confirm that cohabitation with the abuser usually lasts for several years and that violence is more common when the victim resides with the aggressor, coinciding with what has been described by other authors.5–8,25 In the same way, some studies emphasise that children are the main group that lives with the victim4,6 and believe that women with more children under their care are at a higher risk of suffering gender violence.4 70% of the women in our series had children and in 80% of cases of cohabitation of the couple, they shared the home with other people. Puente-Martínez et al.14 points out that the presence of other people in the home supposes an element of added stress that functions as a risk factor. In addition, this high percentage of cases in which the couple live with third parties indicates that violence not only has an impact on the two directly involved (victim and aggressor) but others may also be affected indirectly, especially minors. This demonstrates the need to examine the study of victimisation suffered by this group in more detail and to proceed, on that basis, to implement specific care and protection programmes.

Regarding the type of abuse, several authors15–17,26 have shown that psychological abuse is the most common type. However, in our study we found that almost 75% of victims suffered physical abuse, especially in combination with psychological abuse (43.72%). It should be noted that in our series, proven cases of gender violence were analysed, so this higher percentage of physical abuse may show that a conviction is more common when the result of the assault is visible and affects the woman's physical integrity.

As regards the mechanisms of abuse, it is difficult to make a comparison with the published literature since, as pointed out by Sheridan and Nash,12 there is no standardised method for describing how injuries occur. Still, it is considered that striking with the hand, either open (slap) or closed (punches), are the main form of physical abuse.26,27 Our series shows that the most prevalent mechanism is pushing the woman (half of the cases), while slapping and punching occupy the third and fourth place. As for the mechanisms of psychological aggression, several authors26 emphasise insults as the main form of abuse, which is consistent with our results.

The injuries suffered by the victim as a result of the abuse are significant from a clinical, medical-legal and criminological point of view. Our results are consistent with several publications13,28,29 which find that bruises are the most prevalent injuries and that the percentage of women with more severe injuries (fractures, sprains) is low, with figures between 5% and 11%.13,26 Although various research projects, both national and international, indicate that the injuries are usually located on the head, neck and face,13,27 there are other studies which, like ours, show the upper limbs as the main location.29 The characteristics described (bruises on the upper limbs) are compatible with injuries while defending oneself.12

This paper presents certain limitations that must be taken into account. First, its retrospective nature is responsible for the lack of data, especially on certain variables (level of studies, consumption of substances), which were not reflected in some revised files. Second, the results may not be representative of the general population of abused women because of the study's own inclusion criteria (only cases of gender-based violence with conviction, excluding unreported or cases without a judicial decision). Third, it was not possible to determine the risk factors and establish causal relationships due to the lack of a reference population with which to contrast the findings. Despite these limitations, the selected files from closed and proven cases offer a broad and detailed view on the characteristics of gender-based violence. It would be interesting to check if these characteristics are reproduced in other judicial districts and to carry out case-control studies to confirm the risk factors.

In conclusion, we must emphasise that this study describes real cases of gender violence with a final sentence, providing fundamental information that may be useful for clinical and forensic case management and will allow the prevention and treatment measures of this issue to be managed and adapted.

FundingThis study has been subsidised by the Ministry of Science and Innovation (FEM 2010-22350-C02-01 and FEM 2010-22350-C02-02) and the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality (181/12).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Domínguez Fernández M, Martínez Silva IM, Vázquez-Portomeñe F, Rodríguez Calvo MS. Características y consecuencias de la violencia de género: estudio de casos confirmados por sentencia judicial. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2017;43:115–122.