Violence against women is still a serious social and health problem, despite the measures implemented in recent years. The examination of the victims by the forensic doctor in the courts is of great interest since it provides information related not only to the aggression, but also to their social, family, and economic environment. The objective is to use this information to identify groups at risk and improve/implement the necessary measures.

Material and methodsIn this work, the forensic has collected, for 8 years, abundant data on the victims examined in l'Hospitalet de Llobregat. The sample includes 1622 cases of women who have been victims of gender violence. A descriptive study of the population and of the lesions has been carried out.

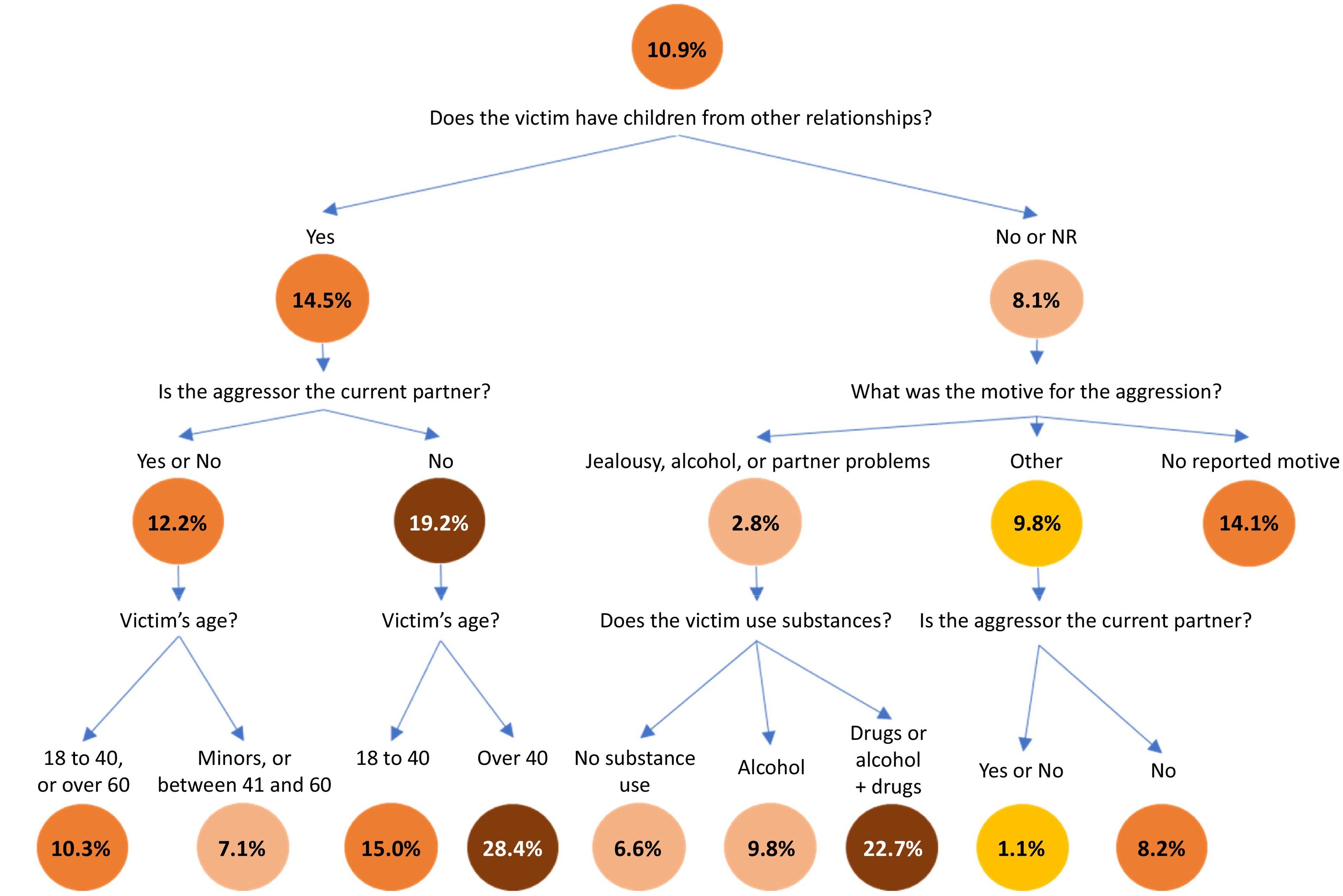

ResultsThe paper presents the main variables studied, both socioeconomic and referring to the aggression itself. This study also analyzes the re-entry of the victims, the repetition of aggressions (revictimization), which are 10.9% of the sample. Finally, the results obtained after applying artificial intelligence techniques—in this case, CaRT classification trees—are presented.

ConclusionsWith the results obtained, we conclude that the treatment of the information collected and systematized from the medical–forensic intervention allows a better understanding of Violence Against Women, from which we can extract suggestions on the adoption of care and support measures for the victims and the most vulnerable groups, as well as administrative resources and the optimization of prevention programs.

La violencia contra la mujer sigue siendo un grave problema social y de salud, a pesar de las medidas puestas en marcha en los últimos años. La exploración de las víctimas por el médico forense en los juzgados es de gran interés puesto que recibe información relacionada no solo con la agresión, sino también de su entorno social, familiar y económico. El objetivo es utilizar dicha información para identificar grupos de riesgo y mejorar/obtener las medidas necesarias.

Material y MétodosEn este trabajo, el forense ha recogido, durante ocho años, una toma abundante de datos sobre las víctimas exploradas en l'Hospitalet de Llobregat. La muestra incluye 1.622 casos de mujeres víctimas de violencia de género. Se realiza un estudio descriptivo poblacional y de las lesiones.

ResultadosSe exponen las principales variables estudiadas tanto socioeconómicas como referentes a la agresión en sí. Se trabaja también en base a la reentrada de las víctimas o repetición de agresiones (revictimización), que son el 10,9% de la muestra. Finalmente, se presentan los resultados obtenidos tras aplicar técnicas de inteligencia artificial, en este caso, árboles de clasificación CaRT.

ConclusionesCon los resultados obtenidos concluimos que el tratamiento de la información recogida y sistematizada de la intervención médico-forense permite una mejor comprensión de la Violencia Sobre la Mujer, de la que podemos extraer sugerencias sobre la adopción de medidas de atención y soporte a las víctimas y a los colectivos más vulnerables, así como sobre los recursos administrativos y la optimización de programas de prevención.

Gender-based violence (GBV) and specifically violence against women (VAW) is a huge public health problem,1 of great social and legal relevance, and has very serious consequences internationally and in Spain.2 A WHO analysis3 highlighted that worldwide,4 1 in 3 women had been subjected to physical or sexual violence, either by a partner or non-partner. Various international studies confirm this situation worldwide. Therefore, there is no doubt that violence against women must be a priority issue for today's society, and one that requires an interdisciplinary approach.5

Of the actors involved in this approach, the forensic physician plays a leading role in the legal sphere, as the professional responsible for the medical expert assessment of the physical and psychological injuries of the victims and aggressors. Knowledge of the characteristics of GBV and the profiles of the victim and the aggressor can help improve the quality of the expert assessment, especially when an inherent characteristic of these assessments is that they must be performed urgently.6

The aim of the present study was to expand the existing knowledge regarding the characteristics of GBV and VAW in L'Hospitalet de Llobregat (L'H), with, to our knowledge, the largest sample studied in the Spanish forensic field. Applying artificial intelligence (AI) tools on the sample obtained allows us to identify risk groups in a more detailed way and thus propose key forensic indicators to advise in these situations. It also allows us to identify the areas to apply the necessary protective measures for the most vulnerable groups, thus optimizing resources, services, and programmes.

ObjectivesThe objectives of interest of this study are summarized as follows:

- •

To generate criteria for better management of resources for the prevention and care of GBV. Specialized health personnel, mobility resources, better communication with the MMEE (Mossos de Esquadra, autonomous police force of Catalonia), adapting protocols, interpreters in most common languages, possibility of redirection in marginal cases, specific training oriented to the different specific collectives.

- •

To show the usefulness of applying the protocol implemented since 2012 (undertaken by forensic medicine professionals of L'Hospitalet de Llobregat) for the registration of medico-legal data.7

- •

To combine statistical and AI methods for more effective treatment of victim profiles.

For this study, a prospective analysis was performed of a sample of GBV victims evaluated between January 01, 2009 and December 31, 2016 in the judicial district of L'Hospitalet de Llobregat, following a request from the judicial authority (magistrate or Public Prosecutor's Office).

The cases treated included an extensive anamnesis (including housing, work, years of relationship, children, reason for aggression, nationality, etc.), physical examination of the victim by the forensic doctor, as well as a review of the medical documentation and complementary tests included in the case file. An annex is attached with the protocol followed to collect the information. With the data collected in the forensic medical examination of the victim, 4 groups of information were obtained: main characteristics defining the reported episode of GBV, victim profile, aggressor profile, and data referring to the couple's relationship. Data were also collected on fatal victims and women who disappeared during this period (8 years); these data were obtained from the same court and, in the case of fatal victims, were supplemented with data provided by forensic pathology.

A total of 2276 cases were collected in this study. After screening, exclusion of duplicates, and evaluation of the data (excluding those with incomplete data), a total of 654 cases were filtered out, thus a total of 1622 cases with complete data was considered for this study.

Descriptive and exploratory data analysisThe study begins with tabular treatment of the database, following the same criteria as applied by Trias et al.,7 that is, a descriptive and exploratory statistical analysis, with hypothesis testing for acceptance or rejection. Given the structure of the base population and to avoid biases due to the unequal presence of profiles, complementary information was used to quantify the relative population. Data from the municipal census (National Institute of Statistics - INE) was available, as well as integrated information from Habits®8 (geomarketing tool provided by AIS). We used the IBM-SPSS programme.

Treatment of victim profiles. Application of artificial intelligence methodsAlthough descriptive treatment with standard statistical methods allows a first approach to the structure of the population under study, treatment of profiles as a combination of characteristics offers a better understanding of that combination, by using the concatenation of characteristics, the bias that occurs when generally treating each characteristic separately.

AI tools were used to detect features and profiles of higher relative incidence among victims, in the treatment of both severity and revictimization. The method used was Jerome Friedman's11 CaRT10 (Classification and Regression Trees)10 whose transparency allows expert criteria to be integrated with the information contained in the data itself. Other AI methods used in the processing of similar problems, Artificial Neural Nets,12 Extreme Gradient Boost,13 and Random Forest14 were analyzed and rejected in this study, despite their greater predictive capacity, due to the poor traceability of their functioning (VioGen15), the difficulty of integrating the criteria of the forensic physician in the formation of the algorithm and the number of cases available, which can incorporate biases due to overestimation in situations of revictimization.

Likewise, we used the Habits® database8 developed with Big Data techniques, by applying Data Fusion and Ecological Inference (copulas of marginal distribution functions).

The greater availability of data enabled a better understanding of different behaviors, resulting in better treatment of victims subjected to more than one aggression (victim re-entry/revictimization. Risk profiles.

ResultsDescription of socioeconomic and temporal characteristicsIn general, we observe that victims tend to be young women. The largest population group is between 18 and 30 years of age, comprising almost half the cases of the sample at 42%. With respect to work activity, women with permanent jobs clearly dominate, being the cases most frequently. Most of the victims do not report substance use (Table 1).

Comparison of severity based on the victim's information.

| Variables | Less severe cases (n=1466) | Severe cases (n=156) | Total (n=1622) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % sev. | |

| T1-Age (n=1622) | (n=1466) | (n=156) | (n=1622) | |||

| Minors | 21 | 1.4 | 5 | 3.2 | 26 | 19.2 |

| From 18 to 30 years | 616 | 42.0 | 66 | 42.3 | 682 | 9.7 |

| From 31 to 40 years | 505 | 34.4 | 53 | 34.0 | 558 | 9.5 |

| From 41 to 50 years | 234 | 16.0 | 22 | 14.1 | 256 | 8.6 |

| From 50 to 60 years | 55 | 3.8 | 8 | 5.1 | 63 | 12.7 |

| Over 60 years | 35 | 2.4 | 2 | 1.3 | 37 | 5.4 |

| T1-Work activity (n=1.543) | (n=1.401) | (n=142) | (n=1543) | |||

| Unemployed | 481 | 34.3 | 56 | 39.4 | 537 | 10.4 |

| Student | 31 | 2.2 | 1 | 0.7 | 32 | 3.1 |

| Permanent employment | 822 | 58.7 | 79 | 55.6 | 901 | 8.8 |

| Other | 67 | 4.8 | 6 | 4.2 | 73 | 8.2 |

| T1-Substance use (n=1.622) | (n=1466) | (n=156) | (n=1622) | |||

| No substance use | 863 | 58.9 | 94 | 60.3 | 957 | 9.8 |

| Alcohol | 570 | 38.9 | 52 | 33.3 | 622 | 8.4 |

| Alcohol and other | 22 | 1.5 | 9 | 5.8 | 31 | 29.0 |

| Other | 11 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.6 | 12 | 8.3 |

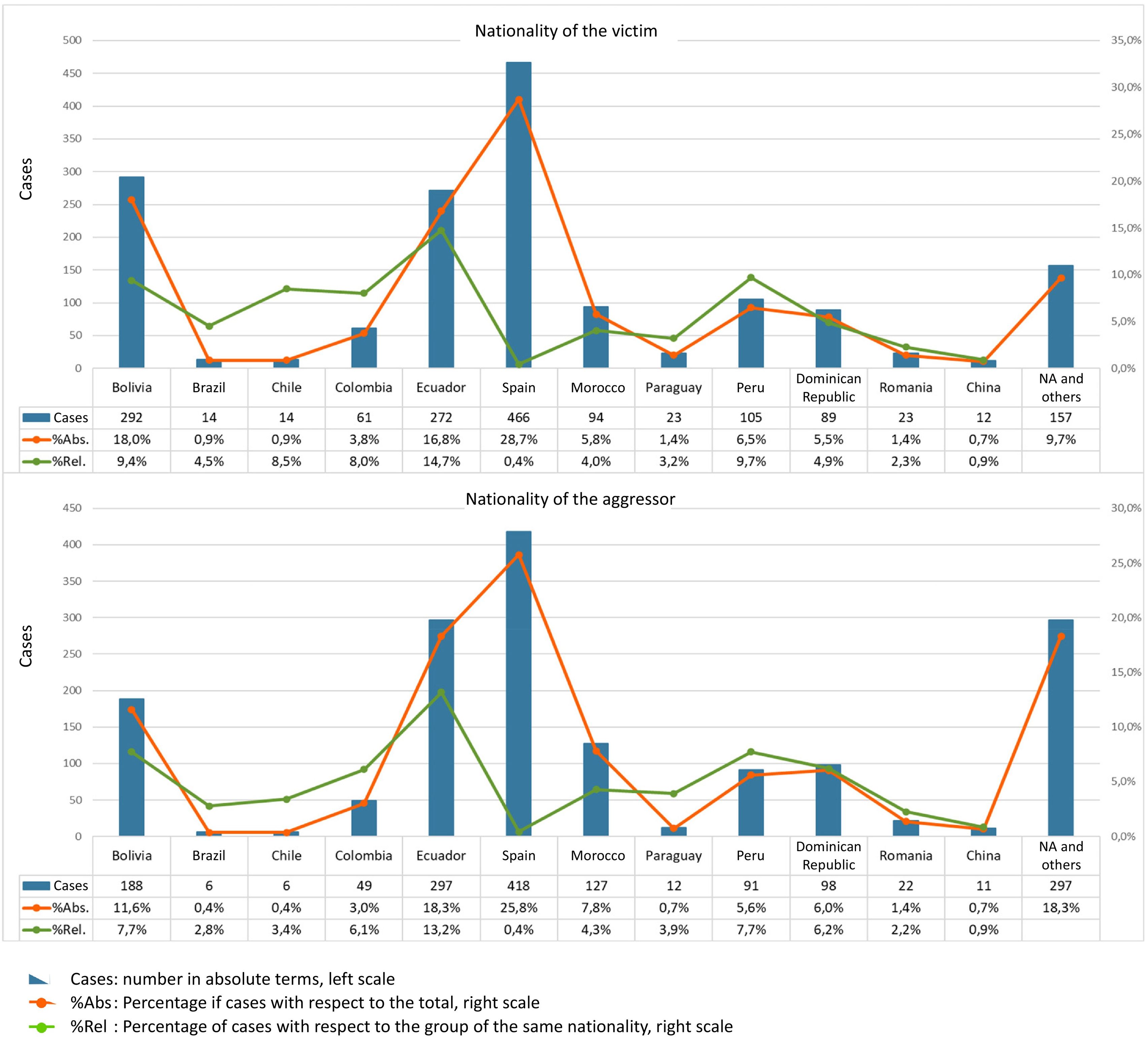

Both the sample data and the data on the nationalities of the inhabitants of Hospitalet during the study period, obtained from Habits®8 were considered for the count by nationality.

In the count by nationality of the victim, a high number of victims with Spanish nationality were observed, 28.7% of the cases attended. However, taking the population into account, the relative percentage drops to 0.4%, which contrasts with the positions for other nationalities such as Ecuador at 14.7%, Peru at 9.7%, and Bolivia at 9.4% (Fig. 1).

Similarly, in the count by nationality of the aggressor, nationalities such as Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia once again stand out.

Detection of this evidence should not lead to a cause–effect value judgment, but to the establishment of specific protection measures and an analysis of underlying causes, such as uprootedness, weakness in the face of crises, and other causes beyond harmful cultural habits.

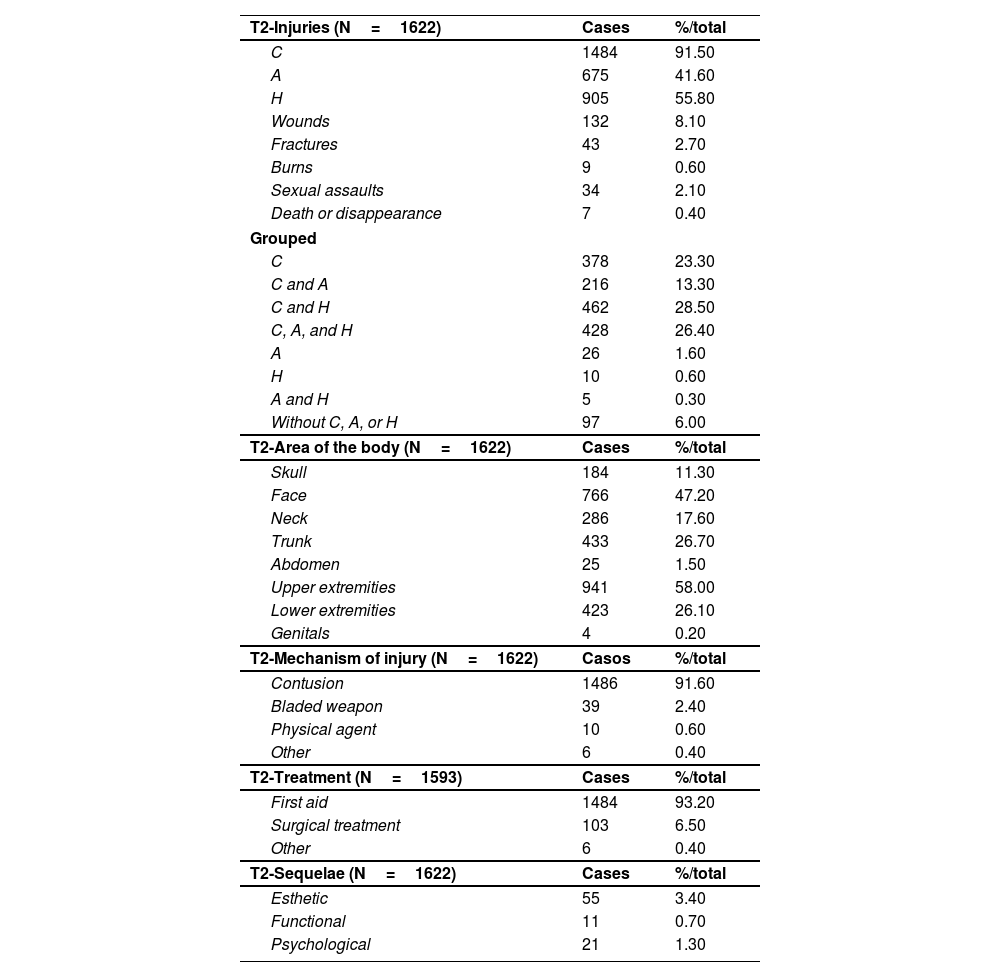

Characteristics of the aggressionTable 2 shows information regarding the characteristics of the aggression, from which the severity of the aggression can be deduced. Contusions are the most common injuries, found in 92% of the victims. In second place are hematomas, which appear in 56% of the cases. The most affected body areas are the upper extremities (58% of cases), followed by the face (47%). The most common mechanism of injury are the contusions themselves (92%), followed by aggression with a bladed weapon (2%). In most cases, initial medical assistance was sufficient (93%). However, surgical treatment was required in almost 7% of the victims.

Characteristics of the injuries.

| T2-Injuries (N=1622) | Cases | %/total |

| C | 1484 | 91.50 |

| A | 675 | 41.60 |

| H | 905 | 55.80 |

| Wounds | 132 | 8.10 |

| Fractures | 43 | 2.70 |

| Burns | 9 | 0.60 |

| Sexual assaults | 34 | 2.10 |

| Death or disappearance | 7 | 0.40 |

| Grouped | ||

| C | 378 | 23.30 |

| C and A | 216 | 13.30 |

| C and H | 462 | 28.50 |

| C, A, and H | 428 | 26.40 |

| A | 26 | 1.60 |

| H | 10 | 0.60 |

| A and H | 5 | 0.30 |

| Without C, A, or H | 97 | 6.00 |

| T2-Area of the body (N=1622) | Cases | %/total |

| Skull | 184 | 11.30 |

| Face | 766 | 47.20 |

| Neck | 286 | 17.60 |

| Trunk | 433 | 26.70 |

| Abdomen | 25 | 1.50 |

| Upper extremities | 941 | 58.00 |

| Lower extremities | 423 | 26.10 |

| Genitals | 4 | 0.20 |

| T2-Mechanism of injury (N=1622) | Casos | %/total |

| Contusion | 1486 | 91.60 |

| Bladed weapon | 39 | 2.40 |

| Physical agent | 10 | 0.60 |

| Other | 6 | 0.40 |

| T2-Treatment (N=1593) | Cases | %/total |

| First aid | 1484 | 93.20 |

| Surgical treatment | 103 | 6.50 |

| Other | 6 | 0.40 |

| T2-Sequelae (N=1622) | Cases | %/total |

| Esthetic | 55 | 3.40 |

| Functional | 11 | 0.70 |

| Psychological | 21 | 1.30 |

A: Abrasions; C: Contusions; H: Hematomas.

From the point of view of protocol formation, it is important to bear in mind that, although contusions are the most common type of injury, they only occur in isolation in 23.3%, and therefore the remaining 68.2% are accompanied by other injuries such as hematomas and abrasions.

Comparative studies of the 2 subsamples: Differentiating elements of severe violence from less severe violenceIn terms of severity classification, according to Echeburúa's typification,9Table 1 shows that the number of cases of less serious violence (n=1466) represents 90% of the sample, which is higher than the number of cases of serious violence (n=156), which represents 10% of the total. We note that the severe cases are mostly young victims between 18 and 30 years of age. However, it is striking that, in the case of aggressions to minors, almost 20% are severe. This increase in the trend is also observed in aggressions to unemployed women, 10% of which are severe. With regard to substance use, we observe that almost 30% of aggressions to victims who consume alcohol and other substances are severe.

Table 1 also shows the comparison of severe and less severe cases, as well as the total and the percentage of severity (severe cases over total cases).

With regard to nationality, the study shows that the most severe aggression tends to involve foreign aggressors or victims, in particular from Bolivia, Ecuador, the Dominican Republic, and Morocco.

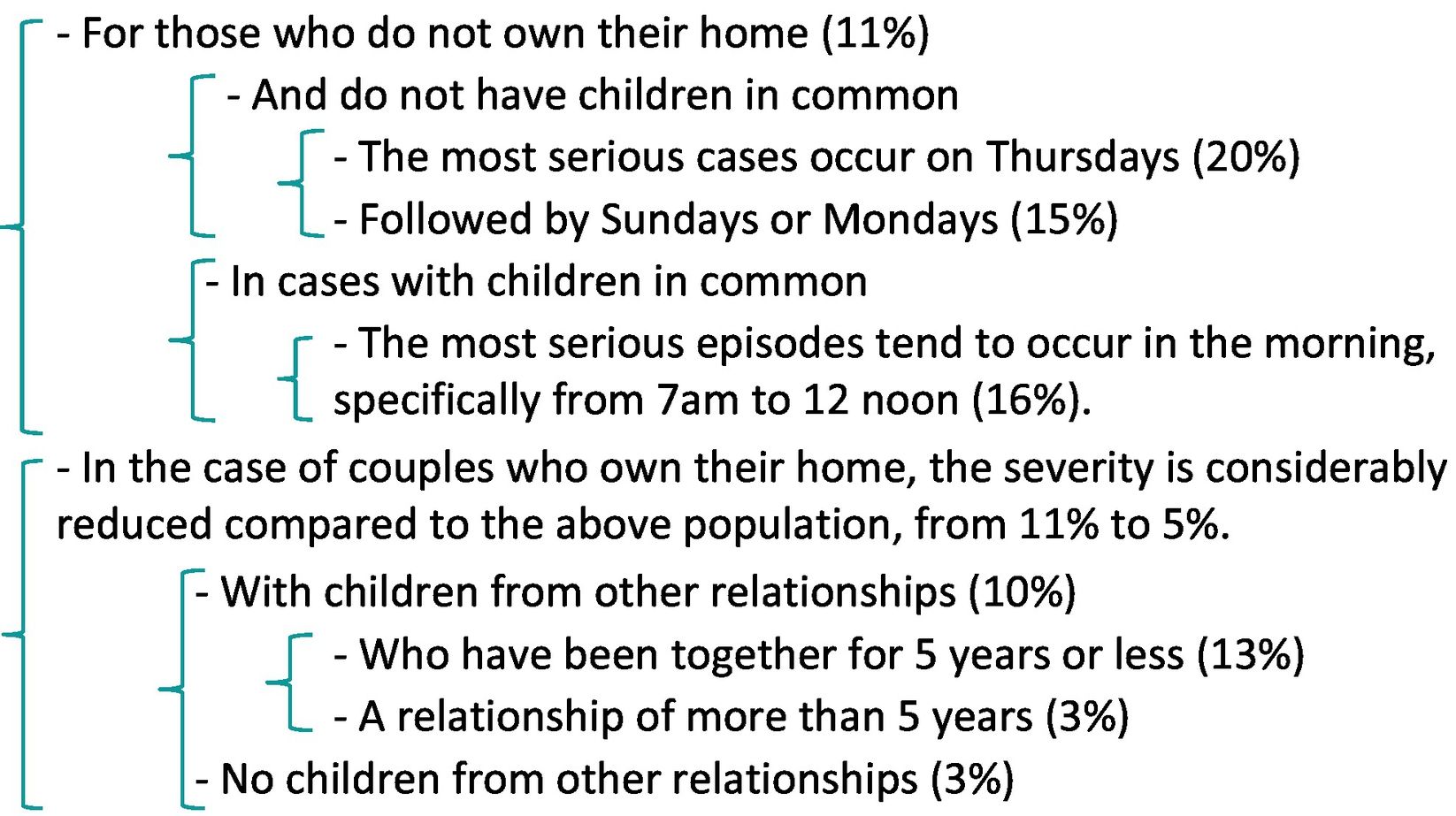

With regard to the situation of the partner, we see that in approximately 2 out of every 3 aggressions, those involved were partners at the time of the aggression. In the case of cohabitation, 59% of those involved live together in the same household. In this regard, the study shows that in practically 2 out of 3 cases the current home is rented, compared to a low 23% of cases who own their home. Likewise, we see more severe cases when the couple is living in rented housing.

With regard to children, it is striking that severe cases in couples who have children in common comprise 7.5% of their group, while those who have children, but from other relationships, show a manifestly higher level of severity, 10.6% of their group.

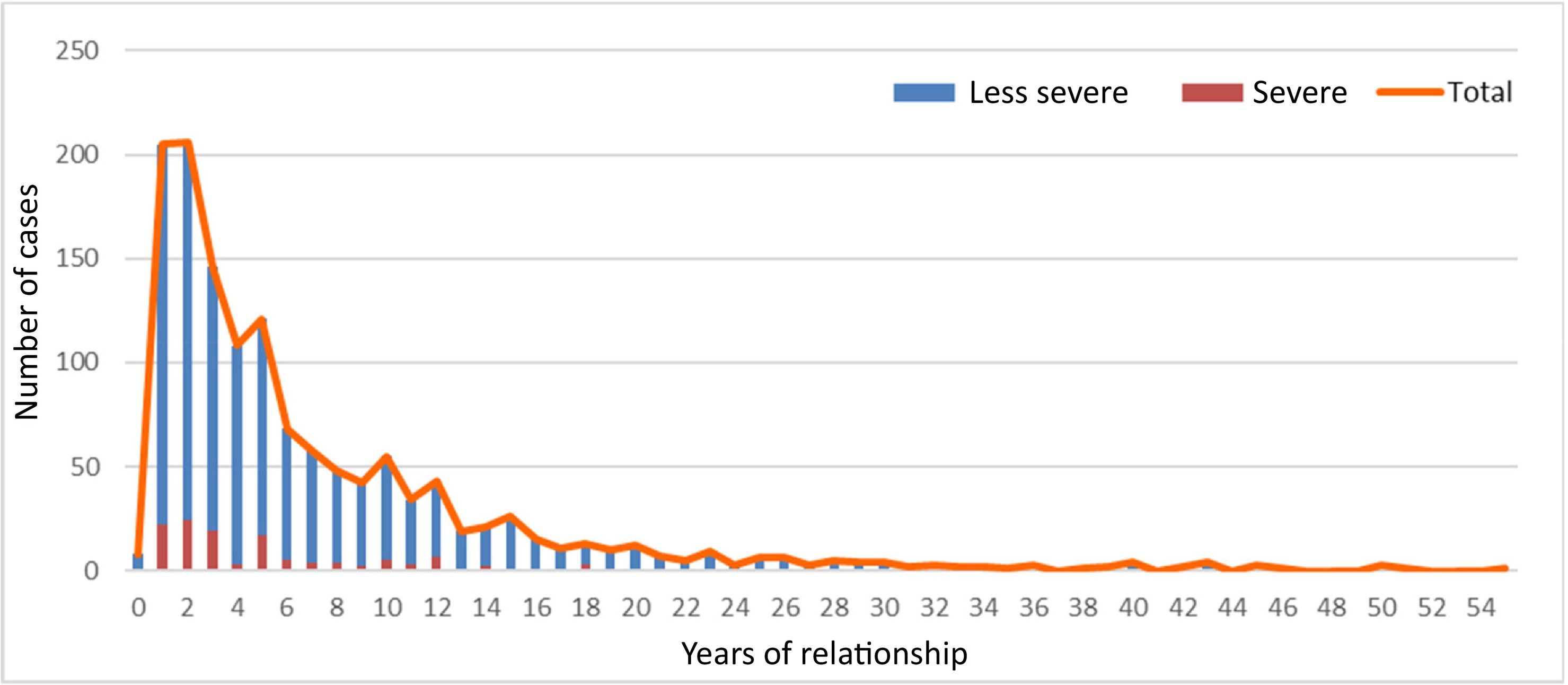

As shown in Fig. 2, it can be seen that the first years of the relationship are when most cases of violence accumulate (more than 30% of the total population). The number of cases decreases after the first 3 years.

Regarding the data on the aggression, it was observed that in 3 out of 4 cases the episode of violence reported was not the first aggression suffered by the victim. However, it is usually the first report.

With regard to the time of the aggression, there was a greater increase in the number of cases during the weekend, 25% of the total cases occurring on Sundays. Likewise, we observe that practically half the aggressions occur in the early hours of the morning in the period between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. (46% of cases). The most severe aggressions also take place at weekends, with 27% occurring on Sundays and 21% on Saturdays.

Looking for a motive for the aggression, we observe that the main motives declared are jealousy, reported by 42% of the population, and relationship problems, 33%, followed by alcohol problems, 28%. Therefore, the motives for the most severe aggressions are primarily jealousy and alcohol.

It can be seen that aggressions occurring in May or in the last quarter have a higher percentage of severity than those occurring over the rest of the year.

Classification model according to severitySeparating in the first instance by housing typology, indicative of economic situation and rootedness/stability, we already find large differences in terms of the seriousness index, indicated in brackets below. Combining these data, we obtain the following results:

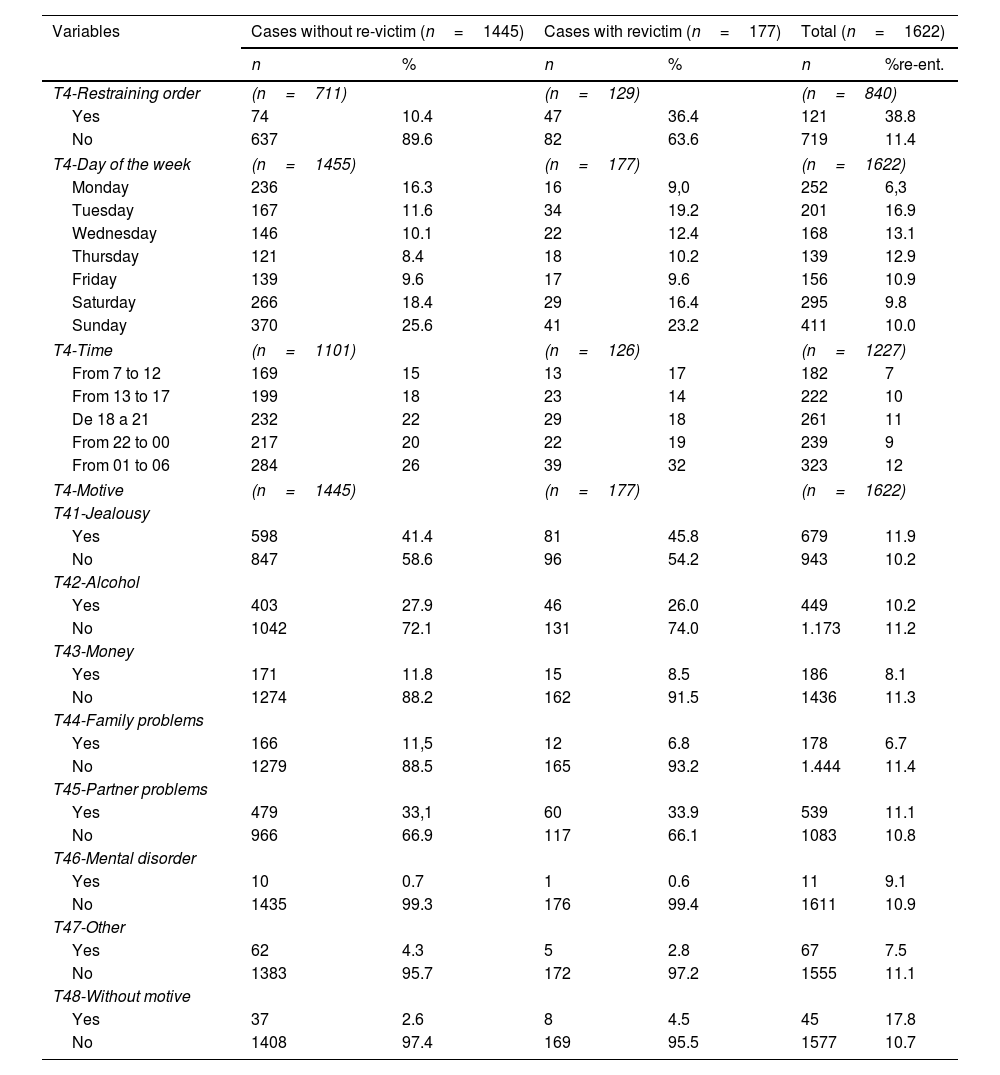

Comparative study of the 2 subsamples: Differentiating elements in the case of revictimization (re-entry of victims)With the information collected, we were able to study the number of visits or aggressions for each victim. Based on this information, all cases not presenting a single visit are treated as re-victimized cases. Specifically, the study included 1445 victims (89.1%) who did not present re-victimization and 177 who did (10.9%). Of these, 149 made 2 visits and 28 made 3 or more (Table 3).

Comparison in re-victimization based on assault data.

| Variables | Cases without re-victim (n=1445) | Cases with revictim (n=177) | Total (n=1622) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | %re-ent. | |

| T4-Restraining order | (n=711) | (n=129) | (n=840) | |||

| Yes | 74 | 10.4 | 47 | 36.4 | 121 | 38.8 |

| No | 637 | 89.6 | 82 | 63.6 | 719 | 11.4 |

| T4-Day of the week | (n=1455) | (n=177) | (n=1622) | |||

| Monday | 236 | 16.3 | 16 | 9,0 | 252 | 6,3 |

| Tuesday | 167 | 11.6 | 34 | 19.2 | 201 | 16.9 |

| Wednesday | 146 | 10.1 | 22 | 12.4 | 168 | 13.1 |

| Thursday | 121 | 8.4 | 18 | 10.2 | 139 | 12.9 |

| Friday | 139 | 9.6 | 17 | 9.6 | 156 | 10.9 |

| Saturday | 266 | 18.4 | 29 | 16.4 | 295 | 9.8 |

| Sunday | 370 | 25.6 | 41 | 23.2 | 411 | 10.0 |

| T4-Time | (n=1101) | (n=126) | (n=1227) | |||

| From 7 to 12 | 169 | 15 | 13 | 17 | 182 | 7 |

| From 13 to 17 | 199 | 18 | 23 | 14 | 222 | 10 |

| De 18 a 21 | 232 | 22 | 29 | 18 | 261 | 11 |

| From 22 to 00 | 217 | 20 | 22 | 19 | 239 | 9 |

| From 01 to 06 | 284 | 26 | 39 | 32 | 323 | 12 |

| T4-Motive | (n=1445) | (n=177) | (n=1622) | |||

| T41-Jealousy | ||||||

| Yes | 598 | 41.4 | 81 | 45.8 | 679 | 11.9 |

| No | 847 | 58.6 | 96 | 54.2 | 943 | 10.2 |

| T42-Alcohol | ||||||

| Yes | 403 | 27.9 | 46 | 26.0 | 449 | 10.2 |

| No | 1042 | 72.1 | 131 | 74.0 | 1.173 | 11.2 |

| T43-Money | ||||||

| Yes | 171 | 11.8 | 15 | 8.5 | 186 | 8.1 |

| No | 1274 | 88.2 | 162 | 91.5 | 1436 | 11.3 |

| T44-Family problems | ||||||

| Yes | 166 | 11,5 | 12 | 6.8 | 178 | 6.7 |

| No | 1279 | 88.5 | 165 | 93.2 | 1.444 | 11.4 |

| T45-Partner problems | ||||||

| Yes | 479 | 33,1 | 60 | 33.9 | 539 | 11.1 |

| No | 966 | 66.9 | 117 | 66.1 | 1083 | 10.8 |

| T46-Mental disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 10 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.6 | 11 | 9.1 |

| No | 1435 | 99.3 | 176 | 99.4 | 1611 | 10.9 |

| T47-Other | ||||||

| Yes | 62 | 4.3 | 5 | 2.8 | 67 | 7.5 |

| No | 1383 | 95.7 | 172 | 97.2 | 1555 | 11.1 |

| T48-Without motive | ||||||

| Yes | 37 | 2.6 | 8 | 4.5 | 45 | 17.8 |

| No | 1408 | 97.4 | 169 | 95.5 | 1577 | 10.7 |

Unemployed victims were observed to have a higher percentage of re-victimization than the rest. In terms of substance use, those using substances such as cocaine, heroin, hashish, or others have a considerably greater likelihood of re-victimization than those who do not report substance use, or only report alcohol consumption.

With regard to the situation of the partner, as with the severity of the aggression, there is observed to be a greater likelihood of re-victimization when there are no children in common or when there are children from other relationships. In the latter case, the likelihood of re-victimization almost doubles from 8.5% to 14.5%.

The main motives for re-victimizing aggressions are usually jealousy or relationship problems and most take place in the early hours of the morning, specifically between 1:00 h and 6:00 h and at weekends (Table 3).

Finally, with regard to the level of severity, we see that re-victimization cases tend to be slightly more severe. Specifically, 12.4% of the re-victimization cases are severe compared to 9.3% in the case of those without re-victimization.

Classification model according to re-victimization: Determination of risk subgroupsAs with the study of severity, we made a classification model based on re-victimization. The resulting tree is shown (Fig. 3). The numbers at the different nodes represent the percentage of re-victimization. They are shaded to facilitate understanding.

In summary, it is noteworthy that the percentage of re-victimization is considerably higher in victims with children from other relationships. In this case, the percentage increases when the aggressor and the victim are not partners, rising to almost 30% when the victim is over 40 years old.

In cases where the partners do not have children from other relationships, the highest percentage of re-victimization is found when the motives for the assault were jealousy, alcohol, or problems with the partner, and the victim of the assault is a user of substances such as cocaine, heroin, hashish, etc..

DiscussionThe data collected in this study are based on an exhaustive anamnesis (which includes not only medical history data, but also a description of the violent episode(s), motives for the reported aggression, date and time, frequency of the episodes, etc.), physical examination (description of injuries, location, and mechanism), and additional data such as the length of time of cohabitation or relationship, nationality of both, children in common or not, restraining order, or previous reports.

Following the line developed in the earlier study by Trias et al.,7 where a protocol for the medical–forensic report was proposed, we assessed its usefulness, which is evident in terms of its length and the precision of its questions and closed answers. Statistical validations and analyses of the quality of the information showed a high percentage of high-quality data, with very few rejections and an extraordinarily high level of homogeneity in the responses.

The largest population group are aged between 18 and 30 years.

By nationality, the highest percentages of victims and aggressors are among the foreign population (71% in the case of the victims and 74% in the case of the aggressors).

It is striking that in 3 out of 4 cases, the episode of violence was not the first aggression suffered, but it was the first time that the aggressor was reported. In other words, it is clear that most victims endure several aggressions before formally filing a complaint. As for the motive for the aggression, the main motive is jealousy, followed by relationship problems and alcohol. With regard to the time of the assault, we see an increase at weekends and in the time slot between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. In relation to the mechanism, the most frequent is contusion and the most affected areas are the upper extremities followed by the face.

In terms of the severity of the case, the number of cases of severe violence comprised 9.6% of the sample. In the case of re-victimization, the percentage of re-entry victims was 10.9%.

Many analogies between severity and re-victimization are observed. Generally speaking, more aggressions were detected against unemployed women, 10% of which severe. With regard to substance use, we observed that aggressions on victims who use substances such as cocaine, heroin, hashish, or others, are considerably more likely to be re-victimization and considerably more severe than in those who do not report substance use or only report alcohol consumption. In the case of aggressions to minors, almost 20% are severe, a percentage that is reduced to half for the rest of the age groups. With regard to children, it is noteworthy that we found greater severity and more re-victimization when there are no children in common or when there are children from other relationships. Likewise, in victims who do not own their own home, the severity is also greater.

The results obtained in this study are comparable to those obtained in 2009 by Trias et al.7 This study was conducted with a significantly larger sample than the previous study and the level of severity and re-victimization indicator were added.

The classification studied by Echeburúa et al.8 was used to typify the elements of the sample under study and reinforce the concept of severe and less severe victims, as a contribution to the dialog of the judge and forensic evaluator.

In this context, it is very important to detect profiles with specific significance with respect to severity, repetition of aggressions, and absolute and relative frequencies. The greater abundance of data compiled over these 8 years allows analysis of the interactions that form the profiles beyond the treatment of the marginal frequencies of each characteristic, thus overcoming the limitation that had to be assumed due to the data scarcity in the previous study by Trias et al.7

The objectives of the present study are to make further progress in this type of research to obtain more comprehensive results on GBV, and to achieve a common protocol for recording forensic data to obtain a more detailed profile of the victim and the aggressor.

Analysis of the data obtained in the forensic field will help improve the administration of resources to prevent this serious problem. Knowing the relationship between the severity of the aggression and the repetition of aggressions, the socioeconomic characteristics, the geographical location, or the cultural environment, will enable the design of more effective measures with the available resources. These measures depend in large part on knowledge of the cultural and socioeconomic environment. As an example of the importance of this knowledge, we would highlight actions such as the implementation of campaigns oriented to the cultural environment of victims and aggressors, communication through the optimal media, in the appropriate language and culture, treatment of early warnings, and reinforcing the provision of care, or help and surveillance. Knowledge of significant traces will also allow specific policies to be implemented, and the periodic monitoring and evaluation of the key indicators detected.

ConclusionsThe results analyzed in this study, based on quantitative treatment, provide extremely interesting data, not only from a forensic and legal perspective, but also from a social perspective, helping to detect risk factors and therefore incorporate the necessary protective measures.

The abundance of different profiles results in strong interactions between the characteristics treated. The use of AI tools such as CaRT classification systems facilitates the creation of measures that are better suited to the diversity of the population.

The treatment of the information collected and systematized from the medical–forensic intervention allows better knowledge of GBV, from which we can extract suggestions on mitigation measures. For example, the improvement of surveillance by physical and temporal space or the optimization of prevention programmes.

Likewise, we can develop improvements in victim care, such as interpreters in the most critical languages, better management of health resources and means of prevention, without forgetting adapting protocols, and potential planning of education campaigns and information points appropriate to the cultural characteristics of the population.

Continuous availability of critical resources such as accessible interpreters for populations in which we have detected a need (Arabic, Romanian, Chinese), not only in care but also in prevention and training programmes. Knowing the seasonal frequency provides us with information on care needs and mobility needs, for example, reinforcing night/early morning shifts, which is when aggressions are most frequent.

In cases where the victim's statement is conditioned by fear or other cultural pressures, this study can help the medical professional to establish the causes of their injuries, i.e., the correlation between the victim profile and the socioeconomic profile, which will help towards a more accurate diagnosis.

For the concatenation of data, we must also mention the help that the medical professional can give, and the characteristics of the victim (country, having children from other partners, not having a job, etc.).

For the future, these results suggest continuity along several lines:

- •

Establishing the protocol for data collection in the forensic medical examination, with extrapolation to other judicial districts and reproducing the process including recent data to measure the impact of the health, financial, and social crisis caused by the coronavirus.

- •

Formalization of crime correction and mitigation measures. Continuity of these studies to measure their effectiveness. Extension of the protocol to other areas, potential generalization.

- •

Integration with related information, such as MMEE and other sources linked to crime.

- •

Application of more powerful and feasible artificial intelligence methods with a greater volume of information and useful for Big Data16 treatments with a high number of variables from the aforementioned integration.

No funding was received for this paper.

Medical-forensic data capture protocol

- 1.

Name and surname initials.

- 2.

Sex.

- 3.

Date of forensic medical visit.

- 4.

Date of the aggression.

- 5.

Date of care visit.

- 6.

Date of birth and age.

- 7.

Nationality of the victim.

- 8.

Nationality of the aggressor partner or ex-partner.

- 9.

Municipality of the current address.

- 10.

Homeowner, renting, or squatting.

- 11.

Length of relationship and/or cohabitation with the aggressor partner.

- 12.

In the case of separation, time of separation.

- 13.

Prior restraining order (yes or no).

- 14.

Family nucleus in Spain (who you live with, if you live with the victim or otherwise, children living with you, children of another partner/s).

- 15.

Personal medical history.

- 16.

Current substance use.

- 17.

Education.

- 18.

His usual work.

- 19.

Her usual work.

- 20.

What do you think cohabiting with your partner is like (good, fair, or bad)?

- 21.

Manifestations of the facts.

- 22.

1st time or not the 1st time you have suffered injuries through abuse (if it is not the 1st time, when did it start, if you remember).

- 23.

1st time or not the 1st time you have reported it.

- 24.

Injuries and mechanism of injury (less serious, serious).

- 25.

Treatment of injuries.

- 26.

Days to healing.

- 27.

Sequelae.

Please cite this article as: Trias Capella ME, Guardia Villalba R, Trias Capella R. Treatment of the information on gender-based violence. With contributions from artificial intelligence. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reml.2023.04.002.