Corpses identification in events with multiple victims is a challenge and one of the main activities of Forensic Pathology. Legal, humanitarian and social repercussions are derived from the correct identification and also its management, generating a great impact.

The objective of this paper is to present the management and identification process of the 13 deaths that occurred in the bus accident on the AP7 motorway in March 2016 in Freginals (Tarragona, Spain). The rapid identification of fatalities, the different quality control mechanisms used, attention to family members, as well as the proper management of the catastrophe with the human and material resources available are analysed.

Despite the foreign nationality of all the victims, which determined the method of identification, all of them were quickly identified by dentistry, fingerprinting or DNA and were quickly returned to their families and countries of origin. Italy was the country where the largest number of victims came from. The participation of forensic doctors in ante mortem data recovery is highlighted.

La identificación de cadáveres en sucesos con múltiples víctimas es un reto y una de las actividades principales de la Patología Forense. De la correcta identificación y gestión de identificación se derivan repercusiones legales, humanitarias y sociales generando un gran impacto.

El objetivo del presente trabajo es presentar el proceso de gestión e identificación de las 13 víctimas mortales del accidente de autobús ocurrido en la autopista AP7 en marzo de 2016 en Freginals (Tarragona, España). Se analizan las rápidas identificaciones de las víctimas mortales, los diferentes mecanismos de control de calidad empleados, la atención a los familiares, así como la gestión propia de la catástrofe con los recursos humanos y materiales disponibles.

A pesar de la nacionalidad extranjera de todas las víctimas, que determinó el método de identificación, todas ellas fueron identificadas rápidamente mediante odontología, huellas dactilares o ADN y fueron rápidamente retornadas a sus familias y países de origen. Italia fue el país de donde procedían un mayor número de víctimas. Se destaca la participación de los médicos forenses en la recuperación de datos ante mortem.

Forensic intervention in mass fatality incidents (MFI) is a challenge. Several incidents in Spain have led to the development of protocols for action. The plane crash with military victims from Afghanistan in 2003 (known as Yakovlev-42), the suburban train bombings in Madrid on 11 March 2004, to date the deadliest terrorist attack in Europe, and its subsequent investigation commission in the Spanish parliament, resulted in the drafting of Royal Decree (RD) 32/20091 and the creation of the National Technical Commission on Mass Fatality Incidents (CTNSVM). The General Council of the Judiciary (CGPJ), following the earthquake in Lorca (Murcia region, Spain) in May 2011, created its own protocol.2

It should be borne in mind that each incident with mass casualties is different, each has specific characteristics that make it particular in itself. Therefore, each incident has a unique scenario that will define the identification of victims and management strategy.3

The aim of this paper is to present the management process and methodology used for the identification of the 13 fatalities of the bus accident, which occurred on the AP-7 motorway (Mediterranean motorway) on 20 March 2016, in Freginals (Tarragona, Spain).

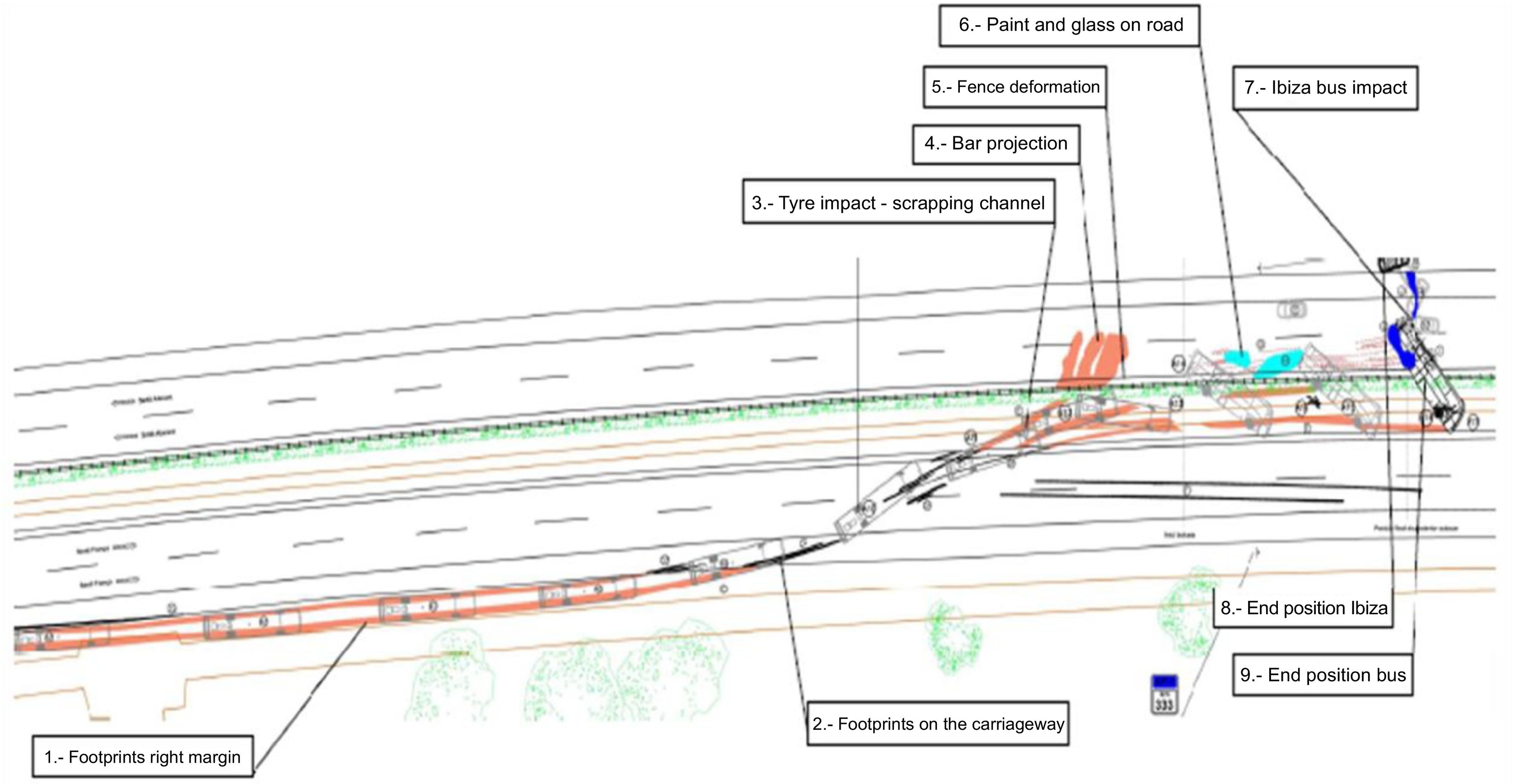

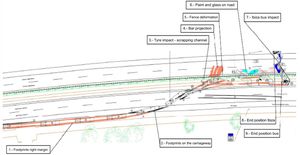

Materials and methodsDescription of the accidentThis was a road traffic accident involving 2 vehicles, a bus, and a passenger car, which occurred at around 06:00 on 20/03/2016 at kilometre point (PK)-333 of the AP-7 motorway, corresponding to the municipality of Freginals (Tarragona, Spain). The bus, which was travelling in the direction of Barcelona, swerved and invaded the right-hand side of the road, making an abrupt manoeuvre to the left losing control, tipping, and skidding over the central reservation of the motorway, finally overturning on the central reservation, occupying the central lanes in both directions (Fig. 1. Image of the police report provided to the judicial proceedings and ceded by the Criminal Court No. 1 of Tortosa Abbreviated Proceedings 30/22).

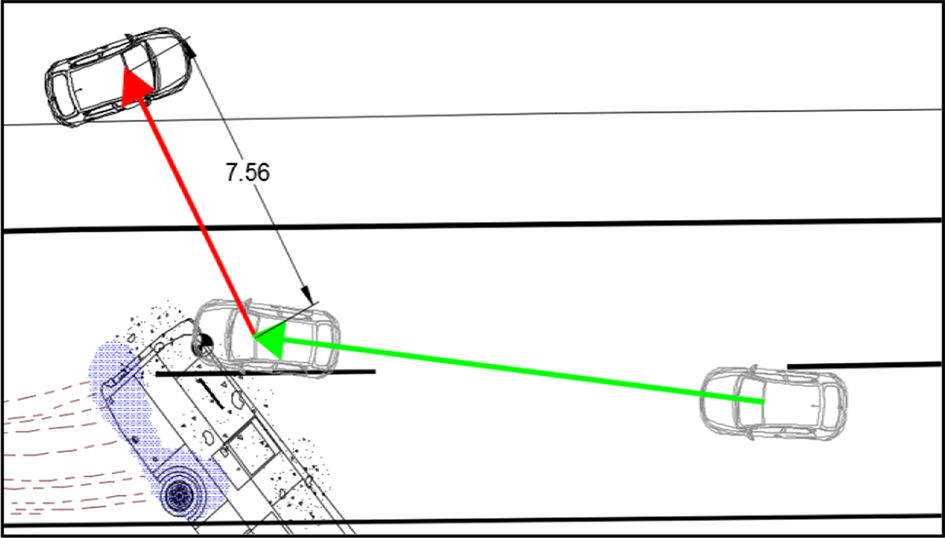

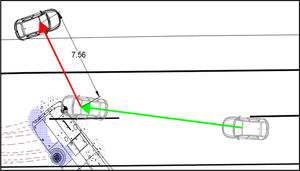

After overturning, another passenger car, which was travelling in the direction of Valencia, crashed into the back of the bus roof (Fig. 2. Image of the police report submitted to the judicial proceedings and provided by the Tortosa Criminal Court No. 1, Abbreviated Proceedings 30/22).

A total of 62 passengers of different nationalities, Erasmus university students and young people of similar ages were travelling in the bus.

The result was 13 fatalities, 24 seriously injured, 18 slightly injured, and 7 uninjured. The bus driver was not killed.

ScenarioAt around 07:48 on the same day as the accident, the judicial commission was set up at the scene, comprising a judge, a lawyer for the Administration of Justice, the Public Prosecutor's Office, and 3 forensic doctors.

At the same time, the CGPJ's Protocol for Judicial Action in Cases of Major Disasters (CGPJ Agreement November/2011) was activated at level 1, as the events did not extend beyond the scope of the autonomous community, and the Crisis Cabinet was set up.

The members of the Crisis Cabinet include the President of the High Court of Justice (TSJ) of Catalonia, who holds the presidency and is responsible for activating this CGPJ protocol and its subsequent monitoring.

The aim of this protocol is to establish the organisational procedure applicable to the agencies and staff of the administration of justice in the event of major disasters. Its functions include the analysis of the event, communication with the CGPJ, control and supervision of information communications and public attention, the coordination structure of the intervening agents, the setting up of provisional judicial premises in other facilities, and the activation of the National Protocol for Forensic Medical and Scientific Police Action (PNAMFPC), RD 32/2009, 16 January.

Once the PNAMFPC has been activated, its objective is to establish a technical and organisational procedure for appropriate cooperation between the different professionals of the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of the Interior, regulating coordinated action between forensic doctors through the Institutes of Legal Medicine (IML), with the Forces and State Security Corporation (FFCCSE) and with the National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences (INTyCF).

The phase of the management of dead bodies and human remains begins, which defines the recovery and recovery area at the site of the accident. Three forensic doctors worked together with police forces in the recovery and recovery area.

The police cordoned off the area, took photographs/videos, recovered, labelled, collected the objects found in the area, and obtained autopsy reports.

The forensic doctors proceeded to list and label each of the dead bodies and personal belongings. The work of the forensic doctors was mainly to differentiate between dead bodies and human remains, make an approximate diagnosis of the date and cause of death, and externally examine the body, and label with the same numbering all the personal effects that were on the body.

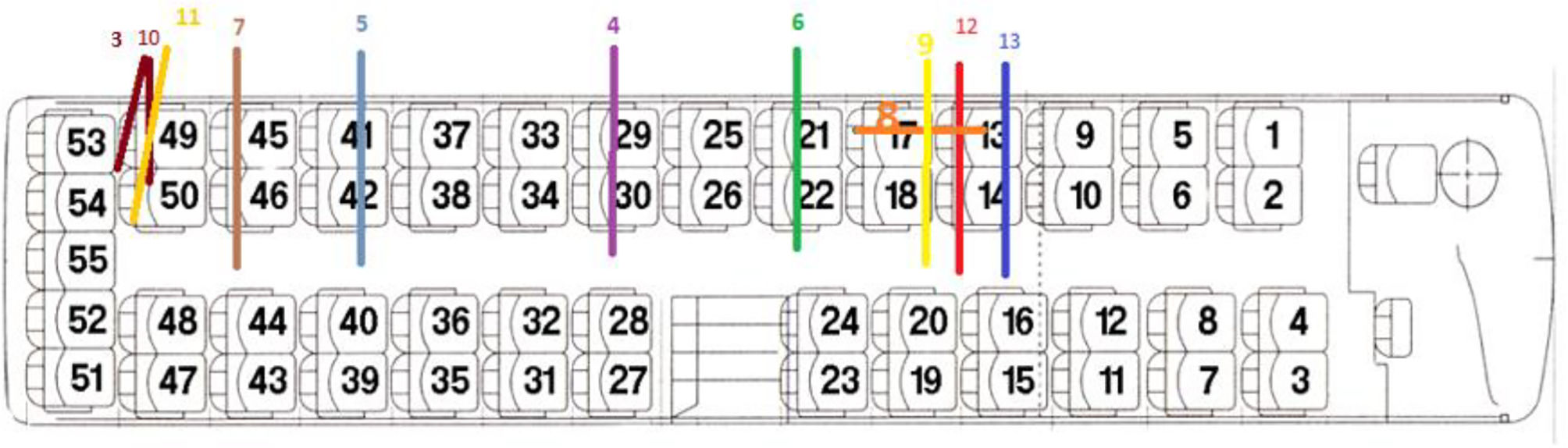

Thirteen fatalities were recovered, 11 of which were inside the bus (Fig. 3) and required removal, the other 2 were on the carriageway.

AutopsiesThe morgue area was located at the headquarters of the Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences of Catalonia, Terres de l'Ebre Division (IMLCFC- TTEE), located in the Tortosa municipal morgue. It is attached to the Santa Creu de Jesús hospital. Three forensic doctors and two forensic pathology technicians (TEPF) from IMLCFC-TTEE were present, joined by two forensic doctors and three TEPF from other divisions of the Institut de Medicina Legal i Ciències Forenses de Catalunya (IMLCFC).

The following work areas were set up in the morgue area:

- Area for the reception of corpses and human remains. This area was staffed by a forensic doctor and a TEPF, who labelled the corpses and personal effects, following the same numbering established for the removal of the body (Removal No./IMLCFC No.).

- Necro-identification-autopsy area.4 Comprising several teams, each with a forensic physician, odontologist, and a TEPF. These teams considered all the bodies as unidentified, following the same methodology, which consisted of obtaining the necropsy report, obtaining DNA samples, dental examination, external and internal examination of the body, and taking photographs.

A standard autopsy of all cavities was performed.5,6 Two special circumstances arose during the autopsies: one required the extraction of both jaws for referral to the IMLCFC, Barcelona Pathology Service (BCN) for radiological study, and a splenectomy was found as an identifying finding in another of the bodies.

- Quality control. Comprising a forensic doctor and a member of the Scientific Police, whose work was to supervise and collect the data obtained by each of the work teams, to ensure the correct methodology.

After verification, the information was forwarded to the Data Integration Centre.

Data integration centreThe Data Integration Centre was made up of forensic medical personnel and members of the Mossos d'Esquadra (MMEE) and was responsible for issuing the corresponding Identification Report, signed by the director of the IMLCFC and the head of the Scientific Police of the MMEE.

Another report on the cause of death was also issued, signed by the forensic doctors of the Pathology Service of the IMLCFC-TTEE.

Antemortem (AM) centreThe main objective of the AM centre was to gather information, without prejudicing specific consideration of the relatives of the deceased and avoiding secondary victimisation at all times.

The antemortem (AM) data collection centre was located in the Parador Nacional de la Zuda in Tortosa because it is in an area where access was controlled and restricted, and isolated from the other the relatives of non-fatal victims.

The team was coordinated by a forensic doctor from IMLCFC- TTEE and also included 2 members of the MMEE corps and an interpreter.7

A work area isolated by screens was set up in the AM centre to provide an area of privacy for the victims' families. The incorporation of the forensic doctor modified the work dynamic initially established by the police forces, which consisted solely of obtaining biological samples from all the family members present for kinship studies (DNA)0.8,9

Thus, a different dynamic was established in terms of the identification methodology, prioritising firstly a unitary registration system matching that used during the recovery of the bodies and in the morgue area. Secondly, it allowed data to be obtained for dental study10 and as a last procedure, genetic studies were conducted by obtaining DNA samples, following this order of priority.

Likewise, the relatives were dealt with in a compassionate manner, to help in managing the mourning process, this compassionate treatment consisted of answering the different questions asked by the relatives and not directly related to the identification process, such as details of the accident, location of corpses, transfer procedures, location of personal objects, among others. Likewise, the victims' relatives were given psychological care by teams of psychologists who were part of the intervention, in the AM area and in the morgue area.

Given the foreign origin of all the victims, a contact circuit was set up with the consular representatives of the different countries to obtain AM dental data.11 The consulates were provided with a generic IMLCFC e-mail address where family members could provide information on: personal data and characteristics (affiliation, personal effects, photos, tattoos, scars, etc.), anthropometric data, medical history, dental reports, and general or dental X-rays. Through the representatives of the different consulates, an agile dynamic was established to contact the different dental clinics in the countries of origin (given that the incident took place in the Easter holidays).

Based on the initial data obtained at the AM centre, direct contact was maintained with the morgue area, with the aim of treating relatives from a humanitarian perspective, to reduce victimisation, and to proceed with the subsequent transfer and accompaniment of relatives to the morgue area, at no time for identification purposes, but merely to assist in the mourning process.

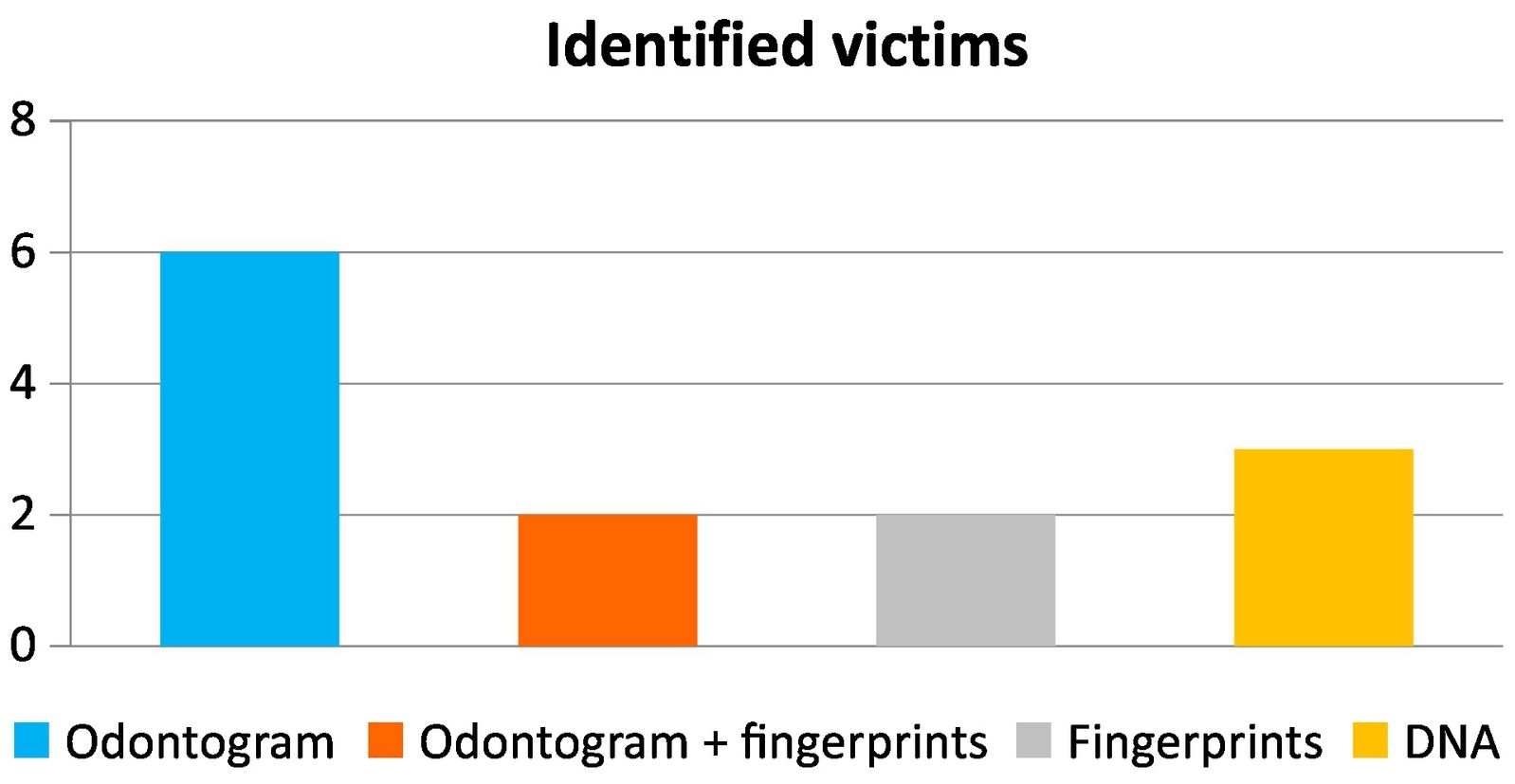

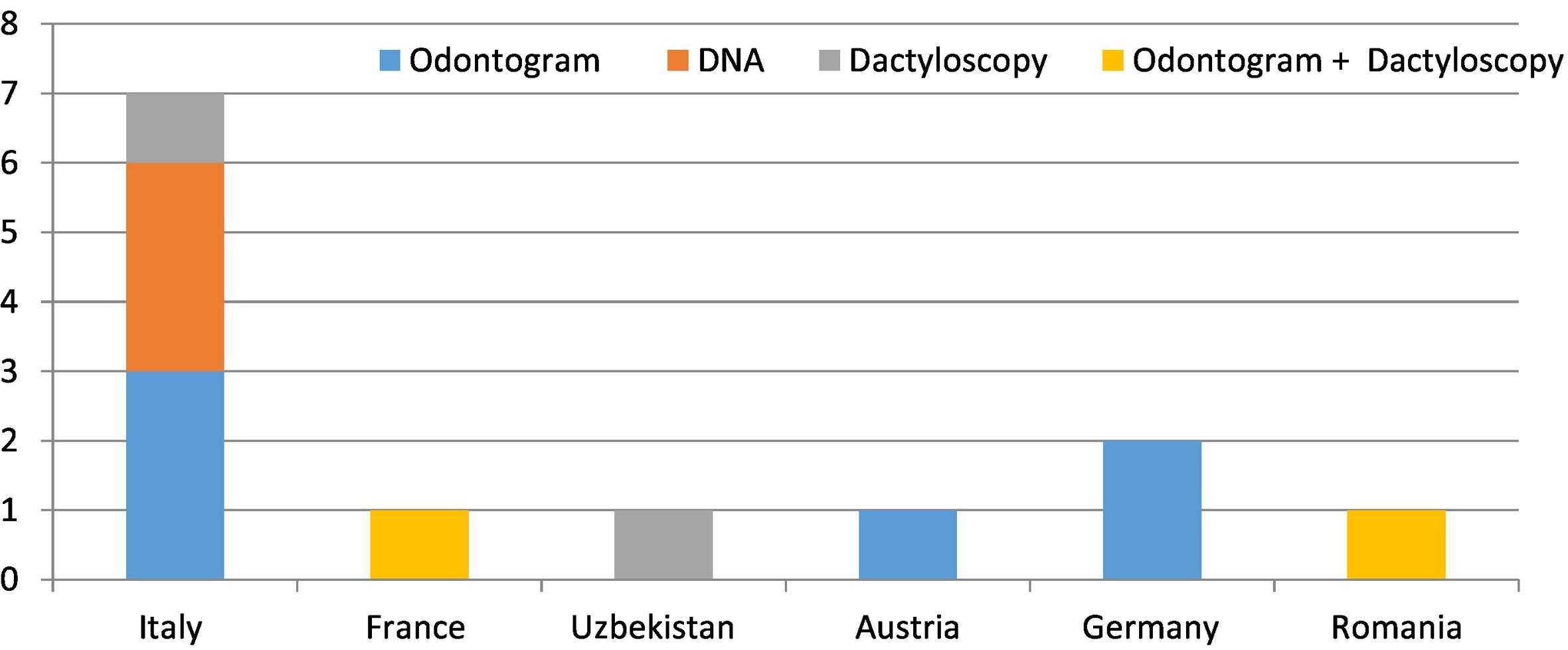

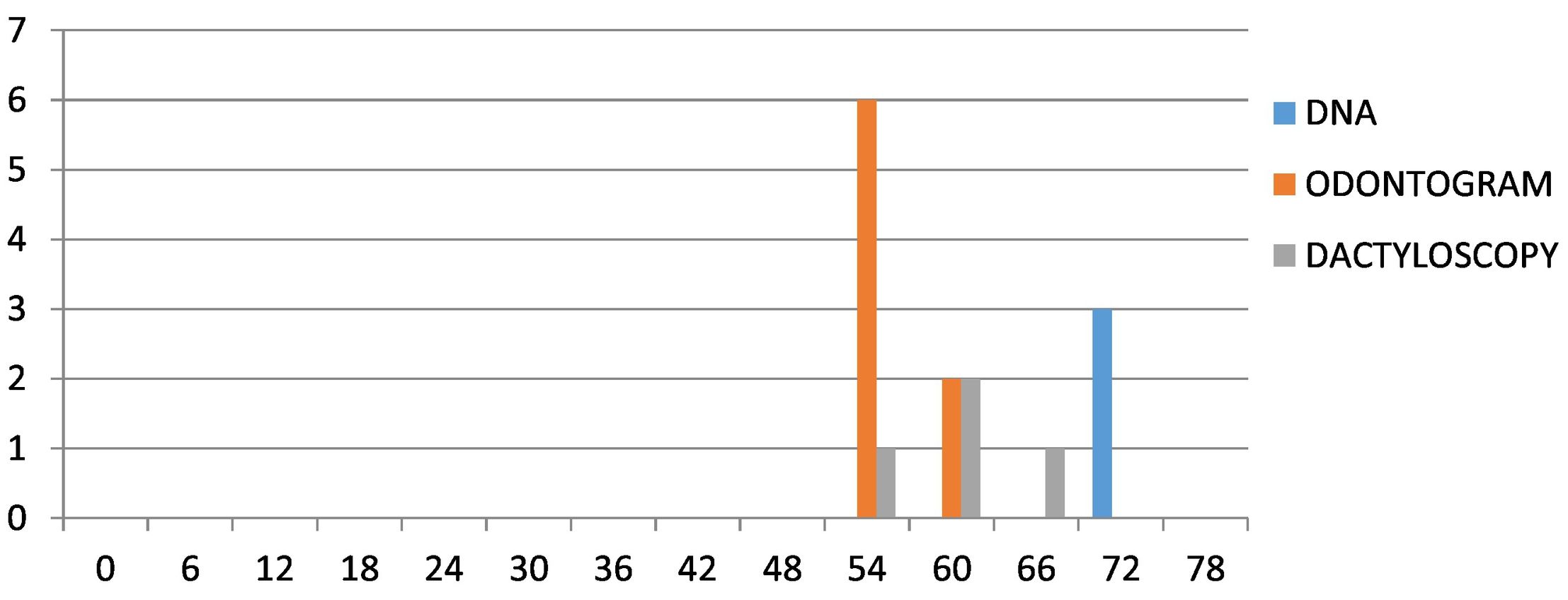

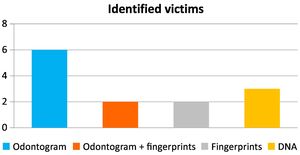

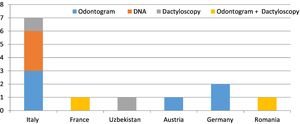

Identification studiesIn relation to the age, sex, nationality, and methods used for the identification of the victims, it is clear that all the women were young and of foreign nationality. The methods for identification in each of the countries of origin were different and there was no uniformity between European countries. It can be seen that 6 of the victims were identified by odontogram, 2 by odontogram and dactyloscopy, 2 by dactyloscopy, and 3 by DNA (Fig. 4, Fig. 5).

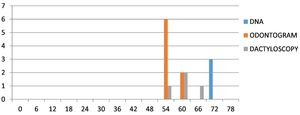

Relating the identification procedure to the chronology of the identifications, in the first place it was observed that most of the bodies were identified within 48–66 h after autopsies by odontogram, with a total of 6 identifications in 54 h. In second place was dactyloscopy, which identified 2 bodies in 60 h. In last place was DNA determination, which took a total of 72 h to identify 3 bodies12 (Fig. 6).

Discussion of the caseA convoy of 5 buses leaving Valencia for Barcelona in the early hours of the morning. The first four arrived at the end of the journey without incident, the last was the vehicle involved in the accident. This was the road traffic accident with the most fatalities to occur in Catalonia since the regional police (MMEE) took over responsibility for road safety (traffic).

The accident that occurred on 20/03/2016 involved a total of 13 fatalities, all of them women, aged between 19 and 25 years old, foreigners of 6 different nationalities, all of whom were living in Spain, studying at the University of Barcelona as part of the Erasmus Project.

The cause of death of all the deceased was severe polytrauma to different anatomical sites.

All the victims were correctly identified according to Interpol criteria. Of the victims, 61.53% were identified by odontogram at 54 h postmortem. A total of 15.39% of the victims were identified by dactyloscopy at 60 h postmortem, and 23.08% of the victims were identified by DNA study at 72 h postmortem.

The bodies, together with their personal belongings, were returned to their families after the corresponding judicial authorisation, the bodies were repatriated successively as they were identified, and the process of transferring the victims was completed 4 days (24/03/2016) after the accident.

The accident occurred in an area located in the south of Catalonia, bordering the Valencian Community, and the expert actions fell to the professionals of the IMLCFC- TTEE, this being the smallest division of the region. Initially, a local response was organised with the subsequent incorporation of forensic odontologists.

This point must be considered to be able to size up the scale of the management of the case in question.

Being able to work within the structure of the Institutes of Legal Medicine (IML)13,14 enabled an organised, agile, early, multidisciplinary, and complete response, regardless of the area of the region in which the accident occurred.

The coordinated work of many IMLCFC professionals (forensic doctors, TEPF, odontologists) together with the heads of the MEEE Scientific Police enabled the rapid resolution of both the medico-legal issues generated, and the mourning process of the victims' families.

Following the established line of work, priority was given by the forensic doctors, in accordance with the provisions of RD 32/2009, and in parallel to the objective of rapid, accurate and scientific identification, to the control of secondary victimisation of the relatives.15 To this end, all IMLCFC staff were available to accompany the relatives from the antemortem area to the morgue area, continuously 24 h a day, as the relatives arrived from their respective countries. For this purpose, it was considered appropriate to physically separate the morgue area from the waiting area for the relatives, and different IMLCFC professionals provided timely and detailed information whenever required.

Also noteworthy in this process of control of secondary victimisation was the performance of the TEPF members of the forensic team who, with their compassionate, caring, and highly professional approach, actively helped in this process of accompanying the relatives.

Their actions in managing the mourning process focussed on thanato-aesthetic intervention on the dead bodies (some of them with significant mutilating injuries), and the physical act of showing the bodies to the relatives.

The relatives received psychological accompaniment and support at all times to manage the grieving process. However, this was not the case for the professionals involved, who, considering the magnitude of the incident and its prolongation over time, also suffered an emotional impact, which should serve as experience to manage future events of similar characteristics. This raises the possibility of offering psychological support to professionals after being involved in similar events.

Initially this was a closed incident (the number and identity of the passengers in the bus were known). However, because the bus was in a convoy of 5 buses and before they set off (from Valencia) there had been changes among the passengers of the different vehicles of the convoy, the information was very confusing as to the identity of the occupants.

Similar anthropometric profiles in terms of racial group, age, and sex can be deduced from this passenger information, which makes the initial presumptive identification more complex.

Furthermore, given the origin of the occupants, their identities correspond to very different nationalities, from both the European Union (EU) and from Eastern Europe. The methods of identification in each of the countries of origin were different, and there was no uniformity between European countries.

Of the 3 scientifically accepted identification procedures, it was decided to prioritise fingerprint and dental identification16,17 in view of the characteristics and peculiarities of the victims (families located in countries of origin).18

Although DNA is the gold standard identification procedure in many countries, in this specific case and in response to media and diplomatic pressure to speed up identification, it was considered that the use of DNA as a method of identification would be a slower process.

The dental identification procedure that was prioritised had an optimal result, because it enabled more than half of the victims to be identified within a period of 54 h. We detected in the AM area an initial lack of coordination and criteria for collecting AM data from the victims' relatives. Once these problems had been detected, it was decided to restructure the area to obtain specific and individual data that would allow identification in an orderly and scientific manner, as well as to maintain close contact with the morgue area.

Fingerprinting has worked well in Spain, if allowed by the condition of the bodies, but limited to Spanish nationals. In addition to following and complying with security standards, according to EU regulations. EU Regulation 2019/1157 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 201919 establishes the security standards, format, and specifications that these identity documents must contain, including the following biometric data: a facial image on the document and 2 fingerprints in digital format.20 However, this identity document is not compulsory under this regulation and is left to the legislative discretion of each member country.

While in Spain these documents are compulsory from the age of 14 in accordance with RD 1553/2005 of 23 December 2005,21 in other countries, such as France, Germany, Austria, Italy, and Romania, although they have them, they are not compulsory.

For example, in Italy, the document is known as Carta d'Identità, where the citizen's identification data, such as full name, fingerprint, photograph, marital status, profession and citizenship, are recorded.

However, in the Republic of Uzbekistan, the biometric passport system has been changing since 2010 and has been compulsory at international level since the beginning of 2016. Therefore, the victim of Uzbek origin and one of the victims of French origin could be identified by fingerprinting.

Interpol's steering group and standing committee on disaster victim identification, which supports its activities in this field,7,8 is considering the creation of a database, on missing persons and unidentified bodies, which will match nominal and forensic data, to assist member countries in solving cases related to both operational work and disasters.

On the other hand, the European agency EU-LISA that oversees major defence and intelligence technology projects, has recently promoted the creation of a biometric matching system.22,23 This project envisages including in its database a register of facial images and fingerprints of more than 400 million people from non-EU countries. This shared system is designed to combat irregular immigration, although it would be of great interest if in the future it could be used as a large biometric databank for forensic use.

However, in this particular case, using a genetic study of DNA could have resulted in a delay in identification because it required relatives to arrive from the different countries of origin, the taking of a sample from relatives and a proven sample from the victim, their submission to the MMEE reference laboratory (MMEE laboratory), and subsequent processing.

In conclusion, the foreign origin of victims of several nationalities complicates the identification process, and therefore we cannot use one single method for all victims. The criterion of prioritising forensic odontology as an identification method made it possible to speed up the chronology of identifications, obtaining a valid and scientific identification of more than 50% of the victims in just under 2 days.24

We would like to thank all the IMLCFC staff for their dedication on the day of the incident and in the days that followed. In particular our colleague the late Leonor Chavarria Cosar, who performed her duties with great professionalism and humanity.

Please cite this article as: Cabús RM, Barbera L, Salort B, Sanchéz I, Soler N, Barberia E, et al. Intervención forense en el accidente de autobús con 13 víctimas mortales en Freginals, Tarragona, Spain. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reml.2023.03.001.