Urgent assistance in primary care is a key area of the health system, being as an important stressor to be claimed for professional liability. The objective was to analyze the professional liability in primary care emergencies of specialists of family and community medicine and their main characteristics in our environment.

MethodsRetrospective descriptive analysis of claims against General Practitioners between 1986 to 2015 was performed.

Results224 claims, all resolved, were analyzed, due to error or diagnostic delay (122%–54.5%), accessibility problems in medical care (48%–21.4%), treatment errors (29%–12.9%) and errors in the issuance of documents (25%–11.1%). In 147 (65.6%) it was urgent assistance and in 77 (34.3%) scheduled. The way of interposition was judicial in 71.4%. In 6 cases (2.6%) the resolution involved compensation in 3 cases of urgent assistance and 3 of scheduled.

ConclusionThe very low risk of claim and compensation payment is confirmed, with no differences found between urgent and scheduled assistance. Clinical safety aspects should be emphasized, especially in the diagnostic error.

La atención urgente en atención primaria es un ámbito clave del sistema sanitario, señalándose como un estresor importante el estar expuestos a recibir reclamaciones por responsabilidad profesional. El objetivo fue analizar las reclamaciones por responsabilidad profesional en la asistencia urgente de especialistas en medicina familiar y comunitaria y sus principales características en nuestro entorno.

MétodosAnálisis descriptivo/retrospectivo de las reclamaciones contra especialistas de medicina familiar y comunitaria entre 1986 y 2015.

ResultadosSe analizaron 224 reclamaciones, todas ellas resueltas, motivadas por error o retraso diagnóstico (122–54,5%), problemas de accesibilidad en la atención médica (48–21,4%), errores en el tratamiento (29–12,9%) y errores en la emisión de documentos (25–11,1%). En 147 (65,6%) se trataba de asistencia urgente y en 77 (34,3%) programada. La vía de interposición fue judicial en el 71,4%. En 6 casos (2,6%) la resolución implicó una indemnización, tratándose de 3 casos de asistencia urgente y 3 de programada.

ConclusiónSe confirma el riesgo muy bajo de reclamación y de indemnización, no habiéndose hallado diferencias entre asistencia urgente y programada. Debe insistirse en aspectos de seguridad clínica, enfatizando en el error diagnóstico.

Primary care (PC), the first point of contact between patients and the healthcare system, is the most widely used level of care by the population, and in Spain the visiting rates are the highest in Europe1. In our context and within PC, emergency care, spontaneous or unplanned care without an appointment has remained stable over recent years, accounting for around 43.1% of the total number of visits2. It is one of the key areas within the medical system.

The professionals who work nowadays in PC seek to resolve patient diseases as quickly as possible, because in many cases their health may be at risk. This gives rise to the risk of prioritizing curing the disease over caring for the patient and their family3, as this may “dehumanise” care and ignore important medical and legal aspects that may affect professional medical liability (PML).

Always being exposed to the risk of being reported or receiving complaints due to supposed medical malpractice has been said to be one of the most stressful aspects of emergency care4. Although the available international5 and national6 data show PC to be a low-risk area for complaints due to PML, it is obvious that the current practice of medicine, especially in emergency or unplanned care, involves risks for the patients and the professionals who care for them. These risks increase with the increasing complexity of diagnostic and therapeutic techniques1.

Nevertheless, the potential value of this as a source of information should be underlined, as the important input from the medical-legal analysis of cases subject to complaint due to presumed malpractice can be used as the basis of a strategy to improve clinical safety. Insuring PML and managing this from a scientific perspective offers a unique opportunity for analysis, publishing information and supporting professionals7 while facilitating learning based on error8.

To discover the nature of the aspects connected with complaints due to presumed PML lodged against Family and Community Medicine (F&CM) specialists during their work in emergency or unplanned PC visits in our context, the relevant complaints managed by the Council of Catalonian Doctors’ Associations (CCMC) were analysed. This analysis differentiated between emergency (unplanned) care and visits by appointment, to study the possible differences between these subgroups.

MethodsThe Professional Liability Department (SRP) of the CCMC managed the main PML insurance policy in Catalonia. Any (civil or penal) judicial or extrajudicial complaint due to PML lodged against an insured party is managed directly by the SRP, which has a historical database of more than 10,000 complaints made since 1986. The doctors and lawyers of the SRP who specialise in PML use a standardised electronic form to register information in the database, using notes and clinical records as sources of data, together with expert reports and evaluations, as well as reports on outcomes and economic factors9,10.

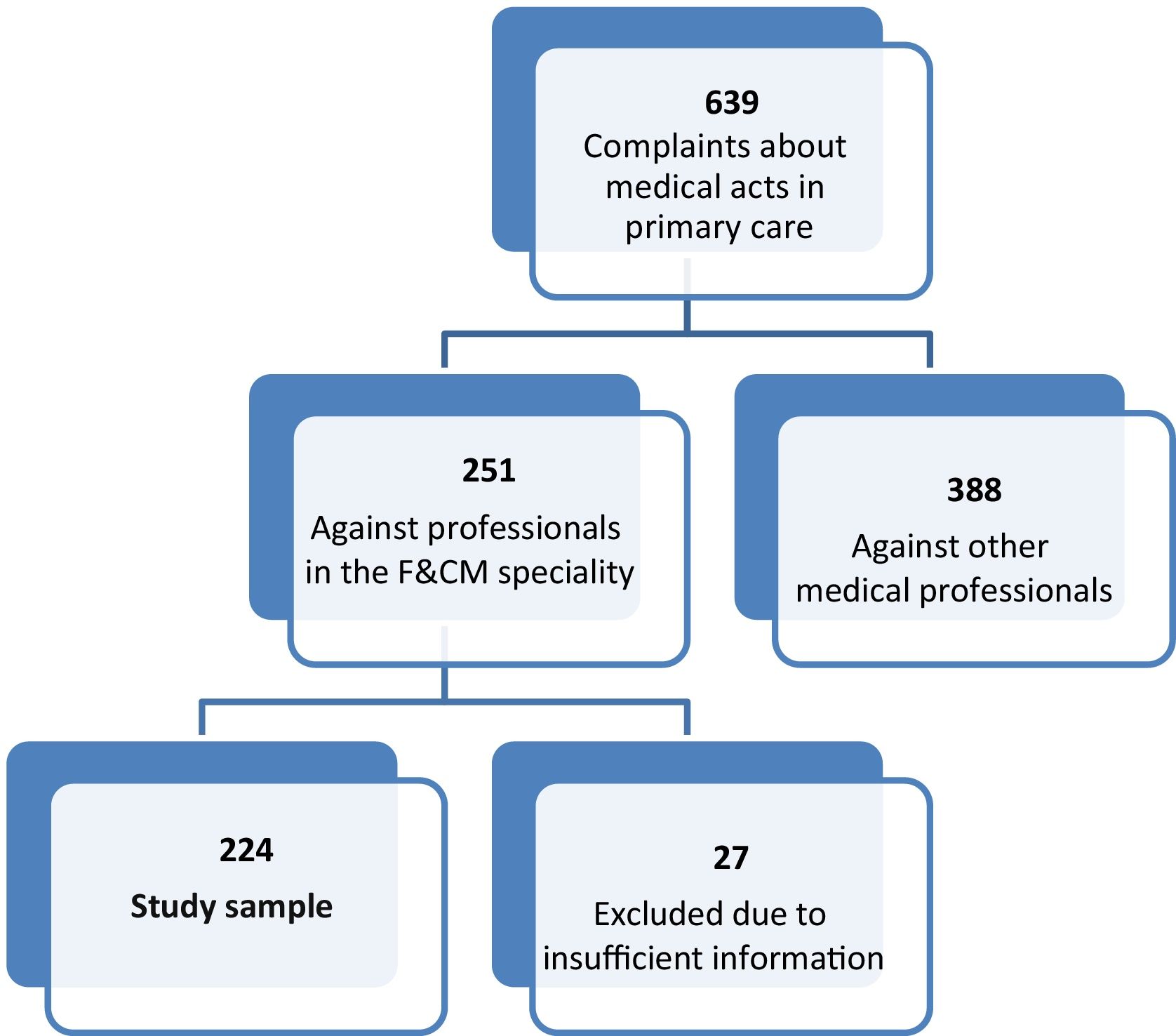

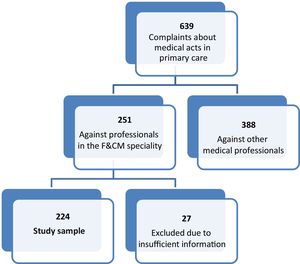

Authorisation was obtained from the CCMC and the files on complaints made in PC were identified and reviewed. The sample selection and screening processes are shown in Fig. 1. A retrospective descriptive analysis was undertaken of the complaints against F&CM specialists who saw a population over the age of 14 years during the period from 1 January 1986 to 31 December 2015. Their clinical, economic and legal characteristics were recorded, paying especial attention to aspects connected with the visit in question, to differentiate emergency (unplanned) care from visits made by appointment. The reasons for complaint were recorded (diagnostic error, accessibility problems, treatment errors or errors in the issue of documents), together with how the complaint was lodged (judicial and penal or civil and extrajudicial). The results of the complaints were also recorded (filed, absolved or sentenced for the judicial cases and resolution or agreement for the extrajudicial ones). The amount in question was recorded for the agreements and sentences. SPSS® (version 24.0) software was used for recording and descriptive analysis.

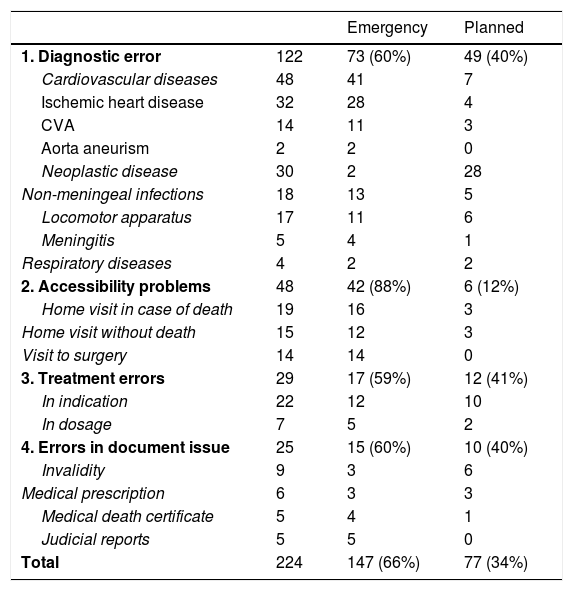

ResultsA final sample for study was obtained of 224 complaints for presumed PML against F&CM specialists, all of which had been resolved. The reasons for complaint were classified according to whether they were due to a diagnostic error or delay (122%–54.5%), problems with access to medical care (48%–21.4%), treatment errors (29%–12.9%) or errors in document issue (25%–11.1%), as well as whether care was provided in an emergency (147%–65.6%) or had been planned (77%–34.3%). Table 1 shows the statistically significant differences according to whether care was emergency or planned, together with the reason for complaint (P = .0047).

Reasons for complaint.

| Emergency | Planned | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Diagnostic error | 122 | 73 (60%) | 49 (40%) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 48 | 41 | 7 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 32 | 28 | 4 |

| CVA | 14 | 11 | 3 |

| Aorta aneurism | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Neoplastic disease | 30 | 2 | 28 |

| Non-meningeal infections | 18 | 13 | 5 |

| Locomotor apparatus | 17 | 11 | 6 |

| Meningitis | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Respiratory diseases | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 2. Accessibility problems | 48 | 42 (88%) | 6 (12%) |

| Home visit in case of death | 19 | 16 | 3 |

| Home visit without death | 15 | 12 | 3 |

| Visit to surgery | 14 | 14 | 0 |

| 3. Treatment errors | 29 | 17 (59%) | 12 (41%) |

| In indication | 22 | 12 | 10 |

| In dosage | 7 | 5 | 2 |

| 4. Errors in document issue | 25 | 15 (60%) | 10 (40%) |

| Invalidity | 9 | 3 | 6 |

| Medical prescription | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Medical death certificate | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Judicial reports | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Total | 224 | 147 (66%) | 77 (34%) |

CVA: cerebrovascular accident.

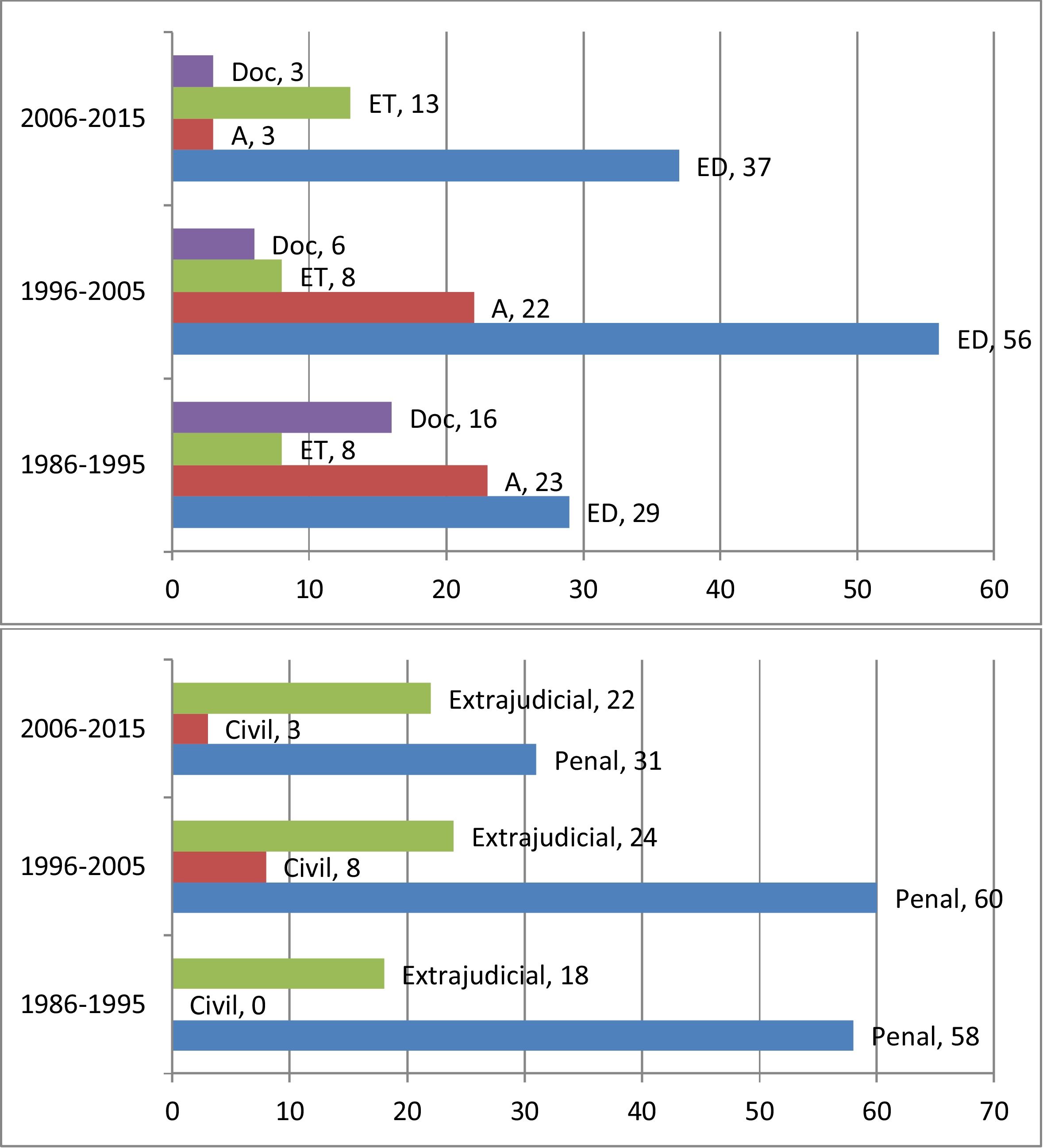

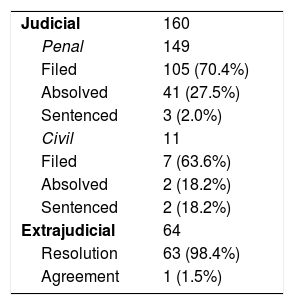

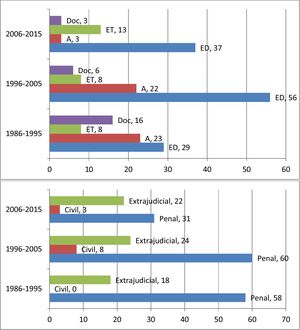

Complaints were lodged judicially in 160 cases (71.4%) as opposed to 64 extrajudicial complaints (28.5%). 149 of the judicial complaints were penal (66.5% of the total) and 11 were civil (4.9% of the total). Fig. 2 shows how complaints were made in each decade.

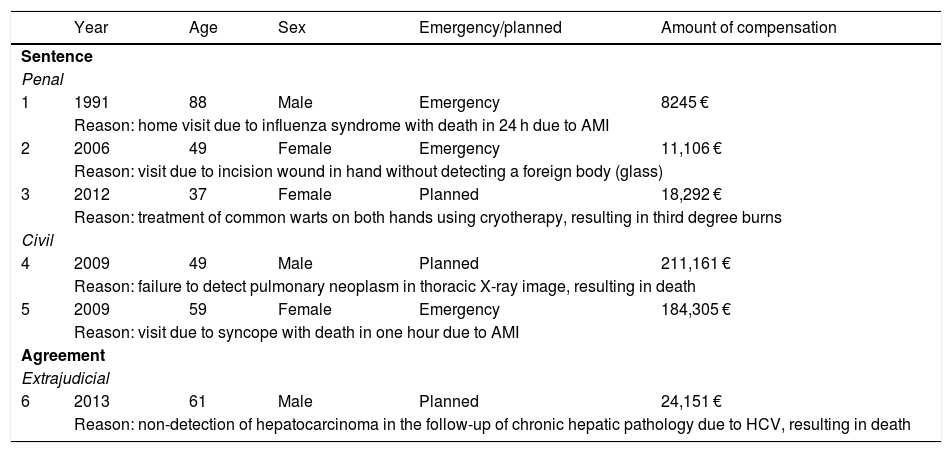

Respecting how complaints were resolved, in 6 cases (2.6%) the plaintiff was compensated in a total of 5 sentences (3 penal and 2 civil), with one extrajudicial agreement. There were statistically significant differences in professional liability according to how the complaint was lodged (P = .0047). The average and median of the amount of compensation in these cases were 76,210 € and 21,221.5 €, respectively, with maximum compensation of 211,161 €. How cases were resolved and the detailed information on those involving compensation are shown in Tables 2 and 3. In 5 of the 6 cases in which compensation was paid a diagnostic error was considered to have occurred, while treatment error was involved in one case. 3 cases involved emergency care (2 penal, one civil) while 3 cases involved planned care (one penal, one civil and one extrajudicial), amounting to percentages of 2% and 3.9%, respectively, without statistically significant differences (P = .4140).

Compensated cases.

| Year | Age | Sex | Emergency/planned | Amount of compensation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentence | |||||

| Penal | |||||

| 1 | 1991 | 88 | Male | Emergency | 8245 € |

| Reason: home visit due to influenza syndrome with death in 24 h due to AMI | |||||

| 2 | 2006 | 49 | Female | Emergency | 11,106 € |

| Reason: visit due to incision wound in hand without detecting a foreign body (glass) | |||||

| 3 | 2012 | 37 | Female | Planned | 18,292 € |

| Reason: treatment of common warts on both hands using cryotherapy, resulting in third degree burns | |||||

| Civil | |||||

| 4 | 2009 | 49 | Male | Planned | 211,161 € |

| Reason: failure to detect pulmonary neoplasm in thoracic X-ray image, resulting in death | |||||

| 5 | 2009 | 59 | Female | Emergency | 184,305 € |

| Reason: visit due to syncope with death in one hour due to AMI | |||||

| Agreement | |||||

| Extrajudicial | |||||

| 6 | 2013 | 61 | Male | Planned | 24,151 € |

| Reason: non-detection of hepatocarcinoma in the follow-up of chronic hepatic pathology due to HCV, resulting in death | |||||

AMI: acute myocardial infarct; HCV: hepatitis C virus.

This work confirms that, although it accounts for a large part of the care that is used the most by the population1, the risk of complaint due to presumed PML in PC F&CM specialists is very low5,6, regardless of whether care is planned or emergency in nature. Moreover, if a complaint is lodged for presumed PML, the risk of a sentence or extrajudicial agreement due to malpractice is extremely low (2.6% of cases, as opposed to 17.3% for all medical specialities)6. This work found no differences in the percentages of extrajudicial agreement/sentencing between emergency and planned care. Additionally, the average compensation for the cases studied is lower than the compensation obtained in other medical specialities in our area6.

Thus although some authors state that very high levels of stress exist in PC emergencies, due to the possibility of being subject to reports and complaints about supposed medical malpractice4, we understand that awareness of the situation as described here should definitively eliminate this concern.

What is more, and in accordance with current trends, when it is broken down into time periods the sample studied shows an increasing tendency to resolve procedures by extrajudicial means, understanding these to be the ideal way to seek solutions for both parties in a conflict in a way that is both simple and functional11. Thus although there is still a lot to be done here, the extrajudicial resolution of CCMC cases involving F&CM specialists increased from 24% in the period 1986–1995 to 39% in the period 2006–2015, with the resulting fall in judicial cases from 76% to 61%. Special mention should be made here of the low rate of sentencing in the penal context (2.0%), in comparison with civil and extrajudicial procedures (18.2% and 15.6%, respectively). We understand that this confirms that the different parties involved should seek a resolution to conflicts of this type outside the penal context.

Nevertheless, in spite of the low risk of complaint and sentencing, information deriving from the complaints made and, even more so, cases of malpractice, should be used to learn from the errors involved8. A case of an undetected pulmonary neoplasm in a thoracic X-ray stands out in this respect. This occurred during a planned visit and led to the death of the patient and the highest compensation paid in our series of cases (211,161 €), which may in our context be described as a catastrophic compensation12. It should be pointed out here that the difficulty found by non-radiologist professionals in interpreting X-ray images has been widely remarked in the scientific literature. Up to 30% of interpretation or reading errors have been found in this situation13, so that it is necessary to continue insisting on the need for training in this field for all medical professionals. In the same way it is also interesting to cite the pathologies which are mentioned the most often in complaints due to diagnostic errors or delays, which represent 55% of the 224 cases studied (122 cases) (Table 1). In figures that agree with those reported in the international literature14, 32 cases involved ischemic heart disease and 14 cases involved cerebral vascular accident. The tumours associated the most often with complaints due to diagnostic error or delay were those of the colon (14 cases) followed by pulmonary tumours (5 cases), as is the case internationally15.

Regarding how reasons for complaint have evolved, although emergency care accounts for 66% of the complaints, contrary to subjective perception the percentage of complaints due to supposed errors in emergency diagnosis and treatment was found to be lower than the percentage of those which arose in planned care (49.6% and 11.5% vs 63.6% and 15.5%). Complaints due to problems with access to care (42 cases vs 6) were those which, at 28.5% of all complaints relating to emergency care, most increased the number of complaints here in comparison with those in connection with planned care.

This fact indicates that, rather than being due to professional medical practice, the complaints lodged may be caused by one or several systemic or organisational factors. This should lead us to consider the need for continuous improvement in organisational processes, circuits and aspects of healthcare, to reduce the number of complaints and adverse events in PC16. The result of the effort made over recent decades in these aspects is shown by the analysis broken down into time periods. This shows that the complaints made due problems accessing PC have fallen from 23 cases (30% of the total) in the period 1986–1995, to 3 cases (5.4%) in the period 2006–2015. Likewise, in the light of the fall in complaints made regarding document issue, the result of medical-legal advice in PC has also borne fruit17. These complaints therefore fell from 16 cases (21% of the total) in the period 1986–1995, down to 3 cases (5.4%) in the period 2006–2015.

In spite of the above considerations, although the small sample size makes it impossible to draw any conclusions in this respect, the fact that cases resolved by compensation are almost exclusively associated with diagnostic error (5 of the 6 cases in which compensation was paid) obliges us to continue working to increase clinical safety in PC.

The improvement in clinical safety in PC necessarily involves a general analysis of all of the aspects of the care that is provided, including clinical, training, organisational and economic factors, together with the express desire to continue learning from our errors16,18,19.

FinancingThis study received no specific support from agencies in the public, commercial and not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Benet-Martí JM, Martin-Fumadó C, Benet-Travé J, Gómez-Durán EL, Arimany-Manso J, Bertran-Ribera MM. Responsabilidad profesional médica en la asistencia urgente de especialistas en medicina familiar y comunitaria. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2022;48:3–9.