There is no clear consensus regarding the best surgical treatment options in patients with hallux rigidus. The present study compares the effectiveness of two commonly used techniques in advanced cases of hallux rigidus: Keller arthroplasty and hemi-implant arthroplasty.

Patients and methodsAll cases of hallux rigidus that underwent surgical treatment with either Keller or hemi-implant arthroplasties during the year 2004 were analyzed. AOFAS scale and angles in A/P X-rays were used to compare at the preoperative moment and at 6 months, 1, 3 and 5 years postoperatively.

ResultsA total of 54feet were included in the study (27 in each group of treatment). No differences were observed between groups in the AOFAS scale in all the postoperative moments analyzed. Significant differences were observed in the AOFAS score and in the complications of the techniques in each separate group by age factor.

DiscussionThe results of the techniques of podiatric surgery of Keller and hemi-implant arthroplasty seem to be dependent on the age of the patient and progress time. Keller arthroplasty has offered better results in patients over 55, independently of the sex, but transfer metatarsalgia at 3 and 5 years is a common postoperative finding. The hemi-implant procedure seems to be more beneficial in patients less that 55.

Actualmente no están claras cuáles son las mejores opciones de tratamiento quirúrgico para los pacientes con hallux rigidus. El presente estudio compara la eficacia de 2 de las técnicas comúnmente utilizadas para el tratamiento de esta dolencia en casos avanzados: artroplastia de resección de Keller-Brandes y artroplastia con hemiimplante.

Pacientes y métodosSe analizaron todos los casos operados en el año 2004 mediante las técnicas de Keller-Brandes y hemiimplante en pacientes con hallux rigidus. Para la valoración, se utilizó la escala AOFAS y diversas mediciones angulares del primer radio en radiografía dorsoplantar en los momentos preoperatorio, postoperatorio a los 6 meses, al año, a los 3 y a los 5 años.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 54 pies intervenidos (27 en cada grupo) en el estudio. No se observaron diferencias entre ambos grupos en la escala AOFAS en ninguno de los momentos posquirúrgicos evaluados. Se encontraron diferencias en cada grupo por separado en la escala AOFAS y en las complicaciones de cada técnica con respecto al factor edad.

DiscusiónLas complicaciones y la satisfacción de las técnicas empleadas en cirugía podológica de Keller-Brandes y hemiimplante parecen ser dependientes de la edad del paciente y del tiempo de evolución posquirúrgico. La técnica de Keller-Brandes ha mostrado ser más ventajosa en pacientes mayores de 55 años de edad, de cualquier sexo, pero al cabo de 3-5 años es común la aparición de metatarsalgias por transferencia. La técnica de hemiimplante parece ser más ventajosa en pacientes de 55 años de edad o menos.

Hallux rigidus deformity can be defined as a degenerative arthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (cartilage degeneration inside the joint that can occur in any other joint of the human body) that is characterized by pain and progressive loss of movement of the joint accompanied with dorsal bone spurs in the base of the phalanx and the metatarsal head.1,2 Hallux rigidus is the second most common disorder that affect the big toe with a estimated incidence of 2.5% in the adult population, although it can appear also in young people with other types of arthritis.3

Treatment of this condition can pose a considerable challenge for the clinician. On one side, conservative measures tend to be ineffective in the long run4,5 and in the other side, there exists controversy regarding which is the best surgical treatment for patients with hallux rigidus, specially in advanced cases. Whereas in the initial cases decompression osteotomies may have a place in the therapeutic armamentum of this condition, in advanced cases surgical treatments are based on joint destruction in the form of resection arthroplasty (Keller procedure), implant (or hemi-implant) arthroplasty or arthrodesis.6,7

Regarding these last techniques, there is no enough evidence yet about which is the best procedure that involves destruction of the joint for advanced cases of hallux rigidus. With the purpose of getting more knowledge with these techniques, the present paper tries to compare the results of the Keller arthroplasty and hemi-implant arthroplasty in a cohort of hallux rigidus patients. This work is intended to compare advantages and disadvantages of both techniques based in radiographic measures, AOFAS scale and complications rates of both techniques.

Patients and methodsPopulationPopulation of the present study was composed by all patients with hallux rigidus in stages III and IV2 that consecutively underwent surgery that consisted in Keller arthroplasty or hemi-implant arthroplasty during the year 2004 in two clinical offices (situated in Madrid and Ciudad Real), where the senior author of this paper (L.D.A.) worked at that time. Patients were followed during 5 years post surgery. Exclusion criteria consisted in the presence iatrogenic hallux rigidus from previous surgeries, neurological diseases, rheumatic diseases, joint infections and osteomielitis, and patients without radiographic or clinical information at 1 year, 3 years and 5 years postop. Because the number of cases in the Keller arthroplasty group was bigger than that of the hemi-implant group, cases of the Keller arthroplasty group were randomly selected till the same number of cases were achieved in both groups. The present study followed the ethical principles for medical research of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.8

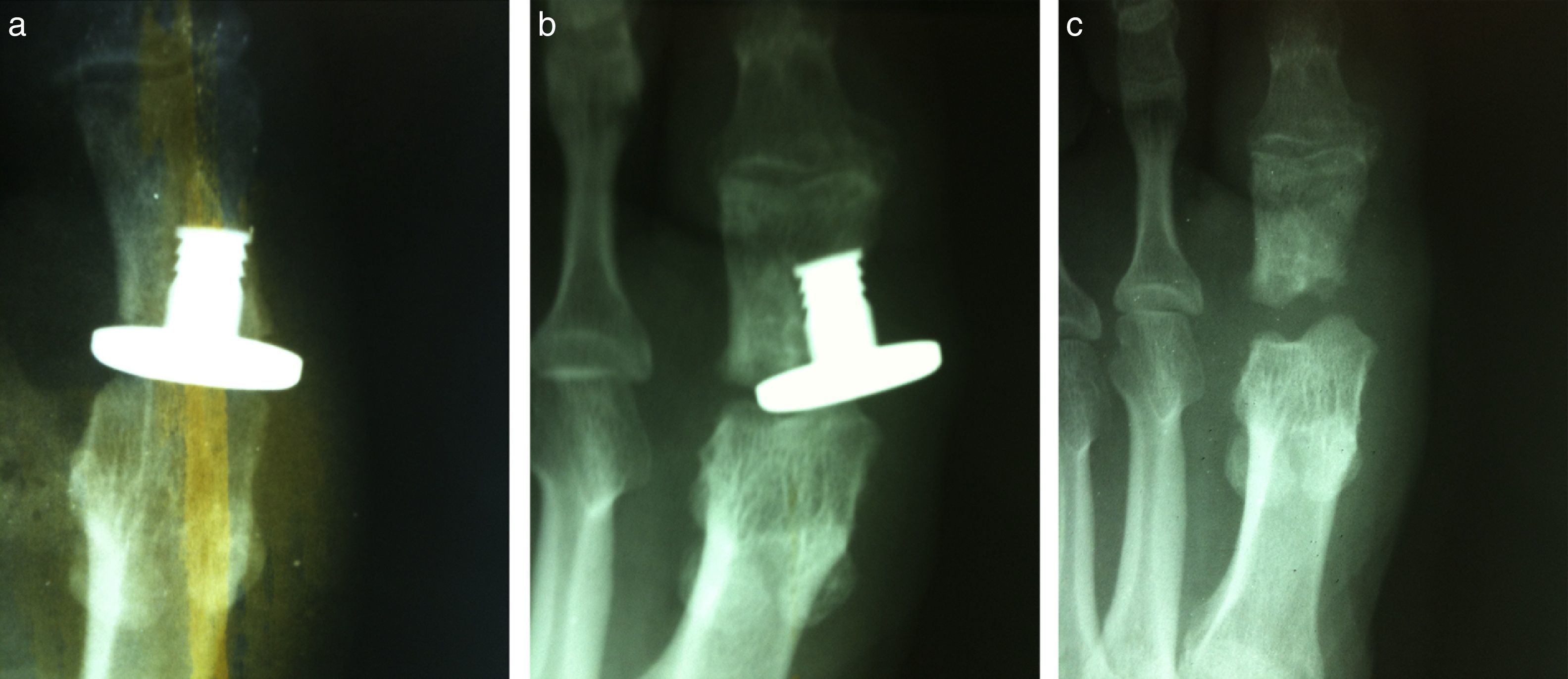

Surgical techniquesAll patients underwent an arthroplasty procedure for the first metatarsophalangeal joint for hallux rigidus treatment by means of a Keller arthroplasty or hemi-implant arthroplasty. All cases were under the care of the first author (L.D.A.), who was also the surgeon who perform all the operations and the followup during the postoperative process. The hemi-implant used was that for the first metatarsophalangeal joint (BioPro©, Port Huron, Michigan, USA). All procedures were performed by a dorsomedial approach following standard procedure techniques described elsewhere.9,10 Both procedures were performed with an inverted “L” capsulotomy and in the Keller arthroplasty group, the capsule was closed in an hour-glass fashion avoiding direct contact between metatarsal head and phalanx in all cases as has been described.11

Variables measuredThe American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle scale (AOFAS scale) for Hallux metatarsophalangeal-interphalangeal joint was applied to all cases.12 The scale was used in the preoperative as well as postoperative at 6 months, 1 year, 3 years and 5 years. The scale has a total of 100 points that are obtained from an interview with the patient (subjective) and a physical examination (objective) that account for 60 and 40 points respectively. Items of pain, function and alignment are used in the scale.13–16 Although not designed for that, the scale can give a general input of the satisfaction of the patient with the intervention.

Angles in antero-posterior (AP) X-ray view were also evaluated in all cases. The radiographic angles that were measured on the pre- and postoperative radiographs (at 6 months, 1, 3, and years) included the intermetatarsal angle between the first and second metatarsals (AIM 1–2°), hallux valgus angle (AHAV) and hallux interphalangeal angle (AIF). All interviews, clinical assessments and radiographic measurements were done by the same investigator, which is the first author of the present paper (L.D.A.).

Statistical analysisAll data was input in a general data matrix created with the SPSS program for Windows (version 15.0). A descriptive analysis was performed by means of the mean 95% confidence interval for continuous variables and percentages of absolute frequencies for discrete variables. For qualitative variables, chi-squared test was performed. For quantitative variables, firstly a one-factor ANOVA test was performed in each group of treatment separately for the AOFAS scale and the radiographic angles being the factor the moment assessment and posteriorly the Duncan multiple range test was performed when statistical significance was positive. Secondly, a multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed in each group separately with the AOFAS scale values in the postoperative period as the dependent variables and variables of age, gender, onset of disease and metatarsal formula used as independent variables. The Duncan multiple range test was again performed as a post hoc analysis. Finally, a multiple analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to assess differences in the AOFAS scale between both groups of treatment (Keller vs hemi-implant) in all the postoperative periods, being the preoperative value of the AOFAS scale de covariance used in the analysis and the postoperative values of the AOFAS scale de dependent variables. A p value of 0.05 was established as the limit to rejection of the null hypothesis.

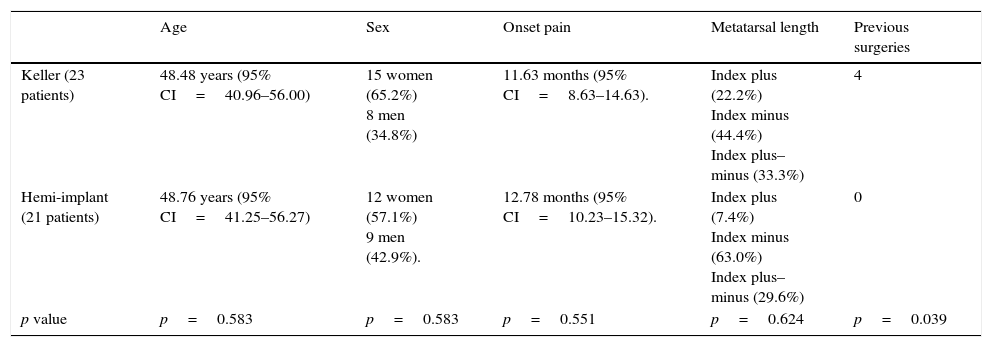

ResultsA total of 54 cases were included in the study (27 cases in 23 patients in the group of Keller arthroplasty and 27 cases in 21 patients in the hemi-implant arthroplasty group). Table 1 shows the demographic values of both groups regarding age, sex, pain progression time and previous interventions in the preoperative period along with the results of the significance test applied between both groups.

Age, sex, onset of pain and metatarsal length and previous surgeries preoperatively in both groups of study.

| Age | Sex | Onset pain | Metatarsal length | Previous surgeries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keller (23 patients) | 48.48 years (95% CI=40.96–56.00) | 15 women (65.2%) 8 men (34.8%) | 11.63 months (95% CI=8.63–14.63). | Index plus (22.2%) Index minus (44.4%) Index plus–minus (33.3%) | 4 |

| Hemi-implant (21 patients) | 48.76 years (95% CI=41.25–56.27) | 12 women (57.1%) 9 men (42.9%). | 12.78 months (95% CI=10.23–15.32). | Index plus (7.4%) Index minus (63.0%) Index plus–minus (29.6%) | 0 |

| p value | p=0.583 | p=0.583 | p=0.551 | p=0.624 | p=0.039 |

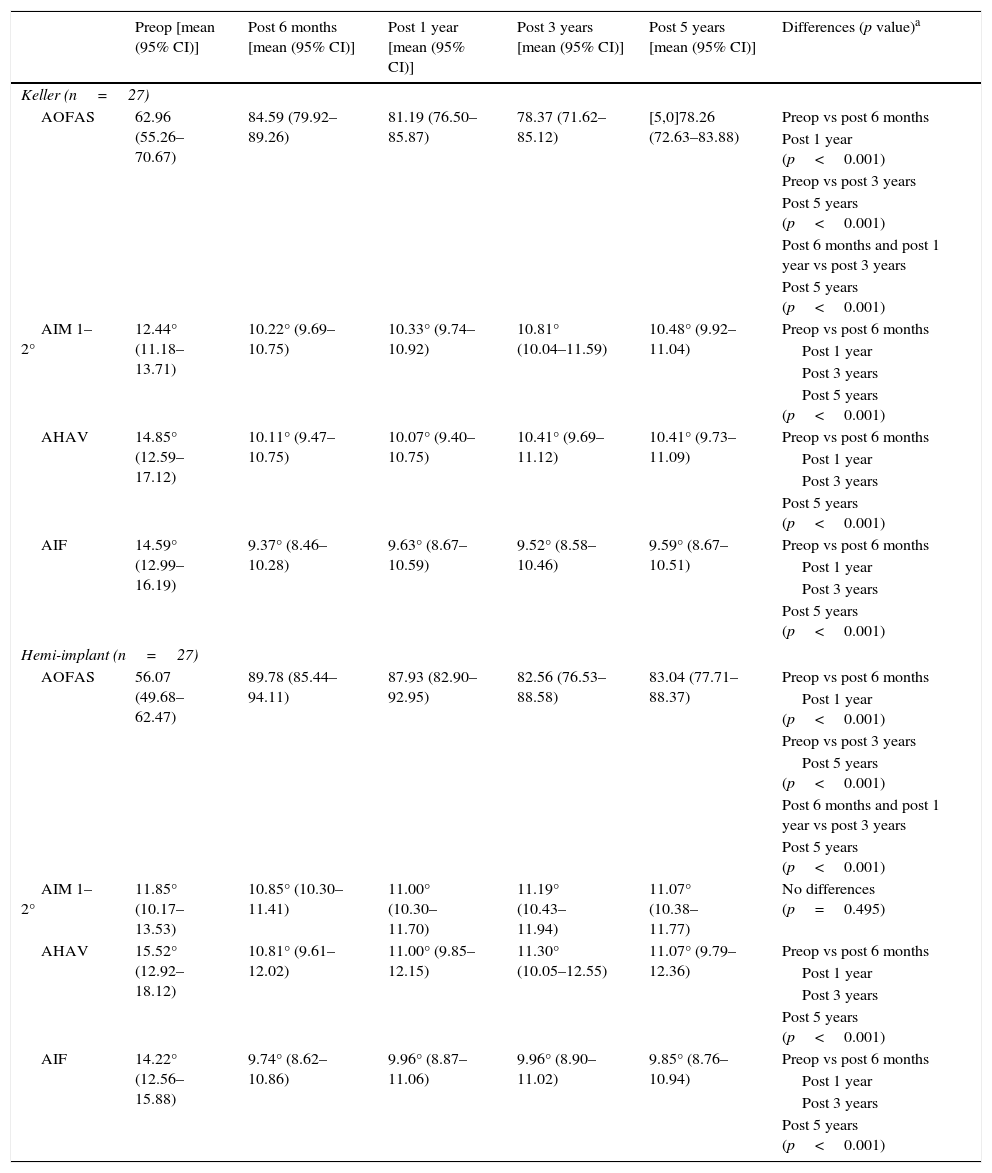

Table 2 shows the means and confidence intervals of the AOFAS scale and the radiographic angles measured in the preoperative and postoperative periods in both groups. An ANOVA test was performed in each group separately comparing the different moment of analysis (preoperative and all postoperative values). Statistical significant differences were observed in all the variables in each group except in the AIM 1–2° in the hemi-implant group. Regarding AOFAS scale, both groups showed the same behavior where three different periods could be identified with the Duncan test: preop period, postop periods at 6 months and 1 year and postop periods at 3 years and 5 years. Regarding de AIM 1–2°, only the Keller arthroplasty group displayed significant differences between the preop and postop measurements. The hemi-implant group showed no differences regarding this angle. The AHAV and the AIF angles had the same result in both groups separately. Significant differences were found (p<0.05) between the preop measurement and all postop measurements in these angles. No differences were found in all the postoperative measurements in any group.

Means and confidence intervals of the variable measured in both groups for the preop and all postop periods measured.

| Preop [mean (95% CI)] | Post 6 months [mean (95% CI)] | Post 1 year [mean (95% CI)] | Post 3 years [mean (95% CI)] | Post 5 years [mean (95% CI)] | Differences (p value)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keller (n=27) | ||||||

| AOFAS | 62.96 (55.26–70.67) | 84.59 (79.92–89.26) | 81.19 (76.50–85.87) | 78.37 (71.62–85.12) | [5,0]78.26 (72.63–83.88) | Preop vs post 6 months |

| Post 1 year (p<0.001) | ||||||

| Preop vs post 3 years | ||||||

| Post 5 years (p<0.001) | ||||||

| Post 6 months and post 1 year vs post 3 years | ||||||

| Post 5 years (p<0.001) | ||||||

| AIM 1–2° | 12.44° (11.18–13.71) | 10.22° (9.69–10.75) | 10.33° (9.74–10.92) | 10.81° (10.04–11.59) | 10.48° (9.92–11.04) | Preop vs post 6 months |

| Post 1 year | ||||||

| Post 3 years | ||||||

| Post 5 years (p<0.001) | ||||||

| AHAV | 14.85° (12.59–17.12) | 10.11° (9.47–10.75) | 10.07° (9.40–10.75) | 10.41° (9.69–11.12) | 10.41° (9.73–11.09) | Preop vs post 6 months |

| Post 1 year | ||||||

| Post 3 years | ||||||

| Post 5 years (p<0.001) | ||||||

| AIF | 14.59° (12.99–16.19) | 9.37° (8.46–10.28) | 9.63° (8.67–10.59) | 9.52° (8.58–10.46) | 9.59° (8.67–10.51) | Preop vs post 6 months |

| Post 1 year | ||||||

| Post 3 years | ||||||

| Post 5 years (p<0.001) | ||||||

| Hemi-implant (n=27) | ||||||

| AOFAS | 56.07 (49.68–62.47) | 89.78 (85.44–94.11) | 87.93 (82.90–92.95) | 82.56 (76.53–88.58) | 83.04 (77.71–88.37) | Preop vs post 6 months |

| Post 1 year (p<0.001) | ||||||

| Preop vs post 3 years | ||||||

| Post 5 years (p<0.001) | ||||||

| Post 6 months and post 1 year vs post 3 years | ||||||

| Post 5 years (p<0.001) | ||||||

| AIM 1–2° | 11.85° (10.17–13.53) | 10.85° (10.30–11.41) | 11.00° (10.30–11.70) | 11.19° (10.43–11.94) | 11.07° (10.38–11.77) | No differences (p=0.495) |

| AHAV | 15.52° (12.92–18.12) | 10.81° (9.61–12.02) | 11.00° (9.85–12.15) | 11.30° (10.05–12.55) | 11.07° (9.79–12.36) | Preop vs post 6 months |

| Post 1 year | ||||||

| Post 3 years | ||||||

| Post 5 years (p<0.001) | ||||||

| AIF | 14.22° (12.56–15.88) | 9.74° (8.62–10.86) | 9.96° (8.87–11.06) | 9.96° (8.90–11.02) | 9.85° (8.76–10.94) | Preop vs post 6 months |

| Post 1 year | ||||||

| Post 3 years | ||||||

| Post 5 years (p<0.001) | ||||||

Abbreviations: AIM 1–2°, Intermetatarsal angle 1–2°; AHAV, hallux valgus angle; AIF, hallux interphalangeal angle.

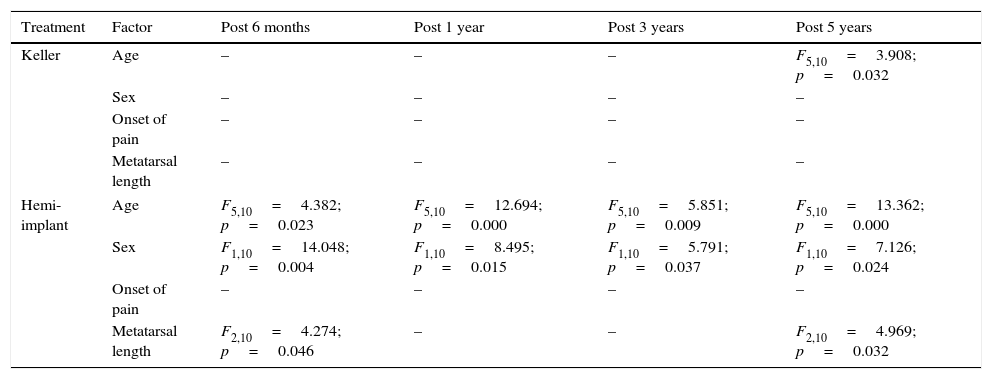

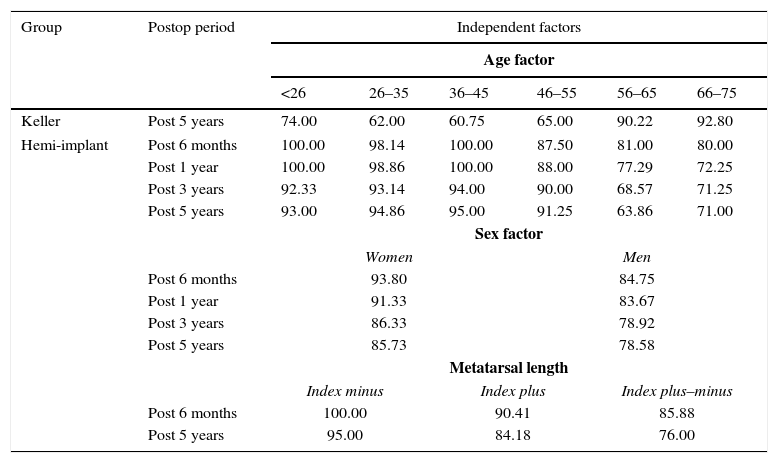

Table 3 shows the result of the multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) for the AOFAS scale with age, sex, pain duration for metatarsal length as independent variables in each group separately. Significant differences were found in the Keller arthroplasty regarding age factor at 5 years postoperatively and in the hemi-implant group regarding the factors age (at all postop periods), sex (at all postop periods) and metatarsal length (at 6 months and 5 years postop). Table 4 shows the post hoc analysis with the Duncan test in cases in which differences were observed. Regarding age factor, in the Keller group at 5 years postop medium and poor results in the AOFAS scale were observed for subjects younger than 55 and excellent results were observed in people older than 55. Regarding the hemi-implant group, excellent results were observed in the AOFAS scale in subjects younger than 55 at 6 months, 1 year, 3 years and 5 years. Results were good for people between 46 and 55 years at 6 months and 1 year postop and subjects older than 55 were associated with medium and poor results in the AOFAS scale. Regarding sex factor, better results were observed in the hemi-implant group in women in all postop periods studied with excellent and good results contrasting good and medium results in men. Regarding metatarsal length, index minus was associated with excellent results in the AOFAS scale at 6 months and at 5 years postop, index plus was associated with excellent and good results and index plus–minus with good and medium results.

Multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) for the AOFAS scale in the postop periods measured with the variables age, sex, onset of pain and metatarsal length as independent variables.

| Treatment | Factor | Post 6 months | Post 1 year | Post 3 years | Post 5 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keller | Age | – | – | – | F5,10=3.908; p=0.032 |

| Sex | – | – | – | – | |

| Onset of pain | – | – | – | – | |

| Metatarsal length | – | – | – | – | |

| Hemi-implant | Age | F5,10=4.382; p=0.023 | F5,10=12.694; p=0.000 | F5,10=5.851; p=0.009 | F5,10=13.362; p=0.000 |

| Sex | F1,10=14.048; p=0.004 | F1,10=8.495; p=0.015 | F1,10=5.791; p=0.037 | F1,10=7.126; p=0.024 | |

| Onset of pain | – | – | – | – | |

| Metatarsal length | F2,10=4.274; p=0.046 | – | – | F2,10=4.969; p=0.032 | |

Results of the post hoc Duncan test for the postop periods when the factor was positive in table III. Notice that homogeneous subgroups of analysis were created for factor age each 10 years.

| Group | Postop period | Independent factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age factor | |||||||

| <26 | 26–35 | 36–45 | 46–55 | 56–65 | 66–75 | ||

| Keller | Post 5 years | 74.00 | 62.00 | 60.75 | 65.00 | 90.22 | 92.80 |

| Hemi-implant | Post 6 months | 100.00 | 98.14 | 100.00 | 87.50 | 81.00 | 80.00 |

| Post 1 year | 100.00 | 98.86 | 100.00 | 88.00 | 77.29 | 72.25 | |

| Post 3 years | 92.33 | 93.14 | 94.00 | 90.00 | 68.57 | 71.25 | |

| Post 5 years | 93.00 | 94.86 | 95.00 | 91.25 | 63.86 | 71.00 | |

| Sex factor | |||||||

| Women | Men | ||||||

| Post 6 months | 93.80 | 84.75 | |||||

| Post 1 year | 91.33 | 83.67 | |||||

| Post 3 years | 86.33 | 78.92 | |||||

| Post 5 years | 85.73 | 78.58 | |||||

| Metatarsal length | |||||||

| Index minus | Index plus | Index plus–minus | |||||

| Post 6 months | 100.00 | 90.41 | 85.88 | ||||

| Post 5 years | 95.00 | 84.18 | 76.00 | ||||

Note that for the age factor homogeneous subsets assigned every 10 years were created.

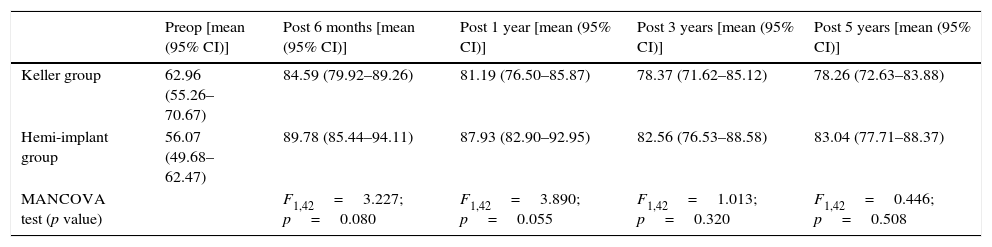

Table 5 shows the multiple analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) to test the effect of group factor (Keller vs hemi-implant) on the AOFAS scale in all the postoperative periods. The preoperative values of the AOFAS scale were used as covariance No differences were observed in any of the postop moments studied between both groups showing that the effectiveness of both techniques are comparable in this study.

Multiple analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) for the effects of the factor groups of treatment (Keller vs hemi-implant) for the values of the AOFAS scale in the different postop periods.

| Preop [mean (95% CI)] | Post 6 months [mean (95% CI)] | Post 1 year [mean (95% CI)] | Post 3 years [mean (95% CI)] | Post 5 years [mean (95% CI)] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keller group | 62.96 (55.26–70.67) | 84.59 (79.92–89.26) | 81.19 (76.50–85.87) | 78.37 (71.62–85.12) | 78.26 (72.63–83.88) |

| Hemi-implant group | 56.07 (49.68–62.47) | 89.78 (85.44–94.11) | 87.93 (82.90–92.95) | 82.56 (76.53–88.58) | 83.04 (77.71–88.37) |

| MANCOVA test (p value) | F1,42=3.227; p=0.080 | F1,42=3.890; p=0.055 | F1,42=1.013; p=0.320 | F1,42=0.446; p=0.508 |

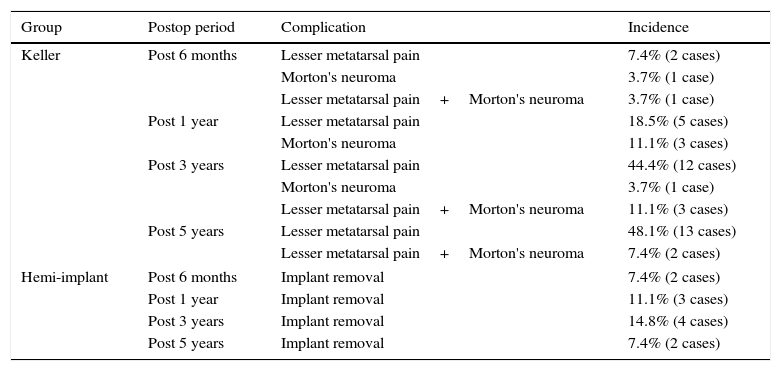

Finally, Table 6 shows all postop complications in both groups. Complications are related as number of cases (ft), not number of patients. Complications are described by their incidence in the several postop periods analyzed. For the Keller group, two complications were observed, isolated or together: metatarsalgia and Morton's neuroma. Maximum incidence of metatarsalgia was at 5 years postop (48.1%) and maximum incidence of Morton's neuroma was at 3 year postop (11.1%). For the hemi-implant group, only one complication was observed and it was the necessity of implant removal by aseptic loosening. Its maximum incidence was at 3 years postop (14.8%).

Incidence of complications in the postop periods in each group.

| Group | Postop period | Complication | Incidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keller | Post 6 months | Lesser metatarsal pain | 7.4% (2 cases) |

| Morton's neuroma | 3.7% (1 case) | ||

| Lesser metatarsal pain+Morton's neuroma | 3.7% (1 case) | ||

| Post 1 year | Lesser metatarsal pain | 18.5% (5 cases) | |

| Morton's neuroma | 11.1% (3 cases) | ||

| Post 3 years | Lesser metatarsal pain | 44.4% (12 cases) | |

| Morton's neuroma | 3.7% (1 case) | ||

| Lesser metatarsal pain+Morton's neuroma | 11.1% (3 cases) | ||

| Post 5 years | Lesser metatarsal pain | 48.1% (13 cases) | |

| Lesser metatarsal pain+Morton's neuroma | 7.4% (2 cases) | ||

| Hemi-implant | Post 6 months | Implant removal | 7.4% (2 cases) |

| Post 1 year | Implant removal | 11.1% (3 cases) | |

| Post 3 years | Implant removal | 14.8% (4 cases) | |

| Post 5 years | Implant removal | 7.4% (2 cases) | |

The present study has performed a comparative analysis of two commonly employed techniques for the treatment of advanced cases of hallux rigidus. The AOFAS scale and several radiographic angles have been used to test the efficacy of both techniques. In general terms, in both groups there exist a growing tendency to satisfaction with the intervention in the postop periods of 6 months and 1 year although a lowering tendency toward 5 years is observed. In the Keller group the following analysis can be done: poor (preop period), <70 points; good (postop at 6 months and 1 year), 80–89 points; medium (postop at 3 years and 5 years), 70–79 points. In the hemi-implant group: poor (preop period); good (postop at 6 months, 1 year, 3 years and 5 years). In this sense, both interventions were rated as good in terms of satisfaction although problems arose at 3 years.

No differences were observed in the AOFAS scale between the Keller and the hemi-implant groups in any of the postop periods analyzed. In fact, results and evolution of the AOFAS scale were quite similar in both groups. The hemi-implant group showed a small benefit over the Keller group although that result showed no statistical significance.

However, the multiple analysis of variance performed showed results that could be clinically important. Although both Keller arthroplasty and hemi-implant arthroplasty showed good results separately in the AOFAS scale, effects by age factor were observed in both groups with opposite results. Patients older than 55 showed better results than patients younger than 55 in the Keller group at 5 years postop. In contrast, patients younger than 55 showed better results in all the postoperative periods in the hemi-implant group. It is the authors opinion that this could be a clinically relevant aspect of the investigation that fits with the general indication of the Keller arthroplasty in older patients.1,4,17–21 However, that is not the case in the hemi-implant group as this technique is usually indicated in patients carefully selected and not young (older than 50).1,22,23

The complication pattern observed in the present study has probably conditioned the results of the AOFAS scale regarding age factor in both groups. Metatarsal pain was the main postop complications observed in the Keller arthroplasty group. They appear basically at 3 and 5 years postop. At 3 years metatarsalgia only appear in subjects of 45 or younger. At 5 years postop, the incidence was of 38.5% in subjects younger than 55 years. In patients older than 55, it only appeared in a 7.7%. This observation agrees with assertion from several authors1,4,22,24–35 although it is important to note the few types of complications seen in this study that can be related to the particular characteristics of this sample. To mention a few, other complications cited by authors of the Keller arthroplasty are: recurrence of the deformity, joint pain, hallux varus, stress fracture of the lesser metatarsals,32,36,37 not functional fail toe22 and loss of purchase of the first digit.21,27 All these complications were not observed in the present study. Regarding the hemi-implant group, the only observed complication was implant removal because of aseptic loosening (Fig. 1a and b). This complication occurred only in patients older than 55 at 3 and 5 years postop and not in younger patients. It is the authors opinion that this results would be influenced by bone quality defects in older patients being the most important factor for the presence of complications in the hemi-implant group. This can suppose a clinically relevant information for the indications of the procedure. Other common complications related in the literature are: loss of weight transfer to the first metatarsophalangeal joint,38 postop joint instability,39 bone cyst formation, local immune response,40 fracture, deformation and/or displacement of the implant, synovitis and osteolysis.20,30,41–44

Regarding radiographic angles measured in the A/P view, both groups had favorable results (correction) in the AHAV and AIF, bringing them back to normal ranges in the postop periods. However, the Keller arthroplasty group displayed improvement in the AIM 1–2° angle from the first postop moment of analysis (postop 6 months) and that effect was not seen in the hemi-implant group in any of the postop periods studied. Reduction of the intermetatarsal angle in the Keller arthroplasty is probably produced by decompression of the retrograde buckling effect of the proximal phalanx on the metatarsal head. This effect is probably not achieved with a hemi-implant arthroplasty because of minimum bone resection of the proximal phalanx for implant insertion.

The present study has some limitations and its results should be used cautiously. The present investigation was observational in nature (not randomized) and, as such, selection biases could have influenced the choice of treatment. Because the procedures were selected on an individual basis after careful clinical and radiographic evaluation by the first author of the paper, this could mean that values of the AOFAS scale and certain angles changed because of reasons that we did not measure and they would be related to the preop evaluation of the cases of the study. Secondly, although all radiographic parameters were measured by the same investigator, a reliability analysis of the measurements were not performed. It is not known if this aspect could have influenced the results obtained in the present study.

In conclusion, the present study has shown advantages and disadvantages of these two techniques of podiatric surgery for hallux rigidus: Keller and hemi-implant arthroplasty. Both techniques have shown similar scores in the AOFAS scale postsurgically at 1, 3 and 5 years postop. However, results in both techniques separately seem to be dependent on the age of the patient. In particular, the Keller arthroplasty seems to be a better procedure in patients older than 55 years, independently of the sex and previous clinical conditions although lesser metatarsal pain can appear at 3–5 years postoperatively. On the other hand, the hemi-implant arthroplasty seems to have less complications in patients younger than 55. This fact could be related to necessity of good bone quality for the implantation of the implant.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of DataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Authors want to thank Javier Pascual Huerta for his technical and statistical assessment in the preparation of this manuscript.