Cladophialophora bantiana is a melanised mold with a pronounced tropism for the central nervous system, almost exclusively causing human brain abscesses.

Case reportWe describe a case of cerebral infection by this fungus in an otherwise healthy 28-year-old coal-miner. Environmental occurrence, route of entry, and incubation period of this fungus are unknown, but our case is informative in that the first symptoms occurred about eight weeks after known traumatic inoculation. Lesions were compatible with tuberculous granulomas, and the patient initially received antitubercular treatment. Melanised fungal cells were seen in a brain biopsy and abscess materials. Therapy was switched from empirical antitubercular treatment to amphotericin B (0.5mg/kg/d), but was changed to voriconazole 200mg/d, i.v. on the basis of antifungal susceptibility test results. The patient responded clinically, and gradually improved. The isolate was identified by sequencing of the Internal Transcribed Spacer domain of rDNA.

ConclusionsGiven the non-specific clinical manifestations of C. bantiana cerebral abscesses, clinicians and laboratory workers should suspect infections caused by C. bantiana, particularly in immunocompromised patients with a trauma history.

Cladophialophora bantiana es un hongo pigmentado con un marcado tropismo por el sistema nervioso central que produce abscesos cerebrales en el hombre prácticamente de forma exclusiva.

Caso clínicoDescribimos un caso de infección cerebral por dicho hongo en un paciente, por otra parte sano, de 28 años de edad y minero del carbón. El hábitat natural, así como la puerta de entrada y el período de incubación de las infecciones por este hongo, son desconocidos, pero el presente caso demuestra que los primeros síntomas se produjeron aproximadamente ocho semanas después de su inoculación traumática. Las lesiones fueron compatibles con granulomas tuberculosos, por lo que el paciente recibió inicialmente tratamiento antituberculoso. Se observaron células fúngicas melanizadas en una biopsia cerebral, por lo que el tratamiento fue sustituido por anfotericina B (0,5mg/kg/d) y fue de nuevo cambiado por voriconazol intravenoso (200mg/d) con base en los resultados de la prueba de sensibilidad antifúngica. El paciente respondió clínicamente y mejoró de forma gradual. El hongo aislado fue identificado por secuenciación de los espaciadores transcribibles internos del ADN ribosómico.

ConclusionesTeniendo en cuenta las manifestaciones clínicas no específicas de los abscesos cerebrales por C. bantiana, los clínicos y el personal de laboratorio deberían considerar la posibilidad de la existencia de infecciones por este patógeno neurotrópico especialmente en pacientes inmunocomprometidos con antecedentes de trauma.

Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis is a severe infection caused by melanized fungi, particularly by members of the order Chaetothyriales (black yeasts and relatives). Infections can be systemic or disseminated and may occur in immunocompromised patients as well as in immunocompetent individuals. Cladophialophora bantiana, with about 150 described cases, the prevalent dematiaceous species from brain abscess, is distinctly neurotropic, causing single-organ infections mostly in otherwise healthy humans, rarely in other mammals.13 Of the 101 cases of primary central nervous system phaeohyphomycosis between 1966 and 2002, C. bantiana was isolated from 48.20 Therapy has not been standardized and these infections have a mortality rate of about 70% despite aggressive medical and surgical treatment and regardless of the host's immune status.20 Since nearly all strains known of C. bantiana are of human origin, the environmental habitat and route of infection of this fungus are enigmatic. In the present report, a case of brain abscess due to C. bantiana in a young man with no predisposing factors is described. The case is informative because the infection could be traced back to a specific injury acquired in a coal mine.

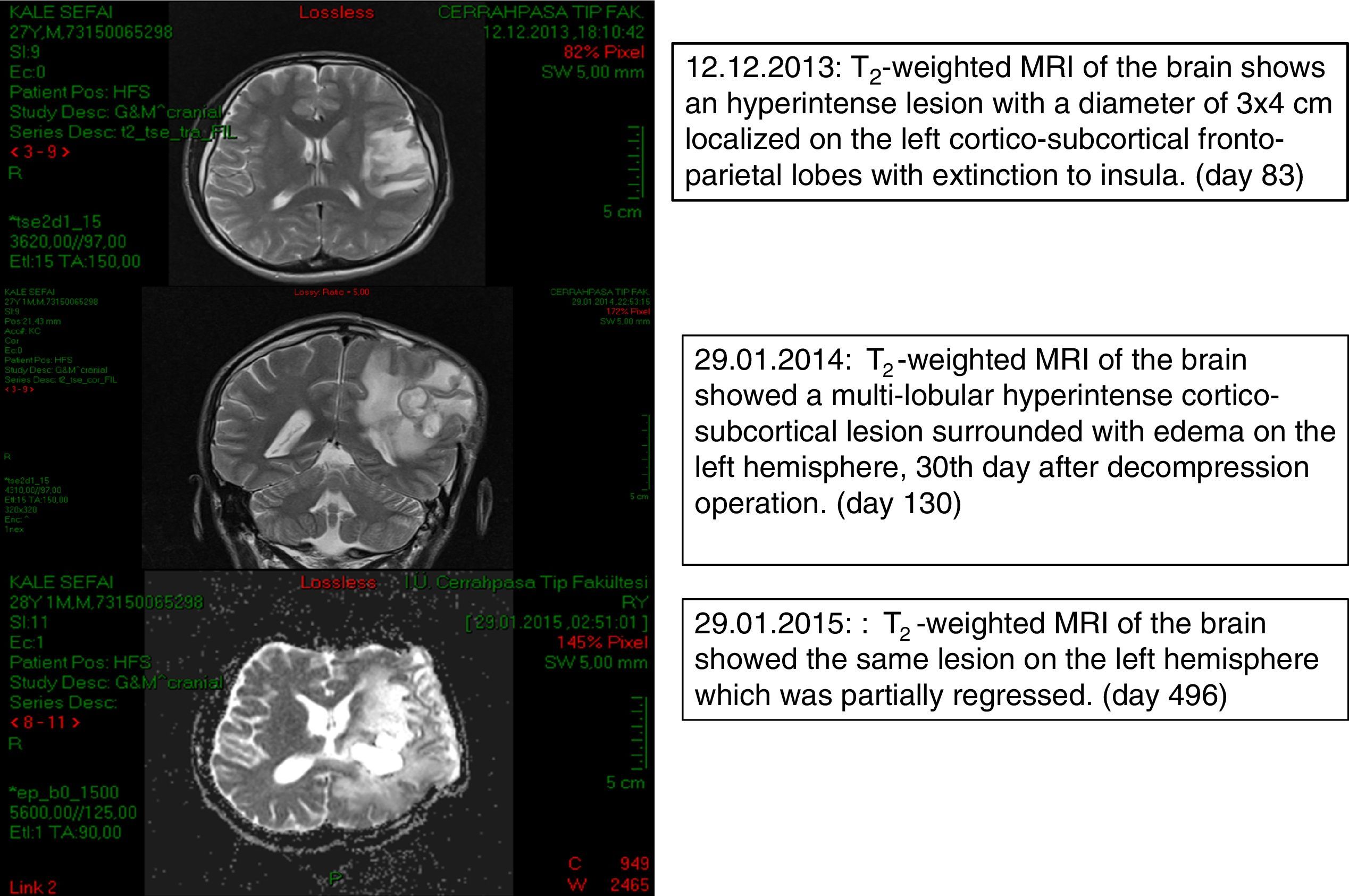

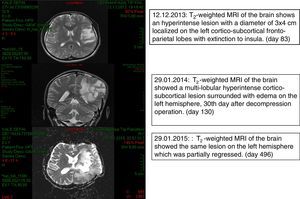

Case reportThe patient was a 28-year-old, Caucasian male, coal miner who was otherwise healthy before having a head injury on September 20th 2013 (day 0) caused by falling rocks while working. He did not lose consciousness and received immediate medical care for laceration of the skin at a local hospital. The skin closure of the open wound was completed using three skin staples from the same staple gun and these were removed 7 days after the injury. He returned to work on day 8 and reported having progressive fatigue from then on. On day 50 he experienced tongue and right arm numbness. On day 54 he had a focal epileptic seizure on the face which recurred on day 56. On day 57 he had a secondary generalized seizure which evolved into status epilepticus. He was hospitalized for 10 days in a state of right hemiparesis. Levetiracetam and diphenylhydantoin treatments were begun, and the patient was transferred to the outpatient clinic of our Neurology Department on day 77. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed multiple masses, the largest measuring 58mm×53mm×33mm, at the left fronto-temporal junction and at the level of basal ganglia with peripheral contrast enhancement and restricted ADC values in their cavities. A significant vasogenic edema surrounded the lesions, compressing the left lateral ventricle (day 83). On day 90 he was readmitted to the Neurology Department with headache, speaking difficulty and right-sided weakness and was hospitalized. He was conscious with expressive aphasia and right-sided hemiplegia. Communication was achieved with facial expressions, gestures or body language. He was investigated for lymphoproliferative disorders. A serological test for human immunodeficiency virus was negative. Biochemical test results, CD4 count and immunoglobulin levels were within normal limits. He developed fever (38.2°C) as well as persistent nausea and vomiting suggesting increased intracranial hypertension. The patient was transferred to the Neurosurgery Department for decompression surgery and a brain biopsy on day 101 and remained one day in the ICU. Methyl prednisolone 1mg/kg/day, meropenem 2g/8h and vancomycin 1g/12h were started (day 102). Since macroscopic appearance of the drainage material was compatible with tuberculous granuloma, anti-tubercular treatment was initiated (day 103). Ehrlich Ziehl Neelsen-acid fast staining (EZN) and polymerase chain reaction excluded an infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (day 107). The patient showed some improvement following abscess drainage and was given liposomal amphotericin B (L-AMB) 5mg/kg/d for the possibility of cerebral aspergillosis (day 105). Histopathological examination of brain biopsy material revealed brown-pigmented fungal elements suggesting phaeohyphomycosis (day 107) which was confirmed by mycological examination at Deep Mycoses Laboratory (day 108). Fungal elements were seen on direct microscopical examination of the sample (day 110). Aerobic, anaerobic, mycobacterial and mycological cultures of the biopsy and abscess material, haemoculture and EZN stains were all negative. Voriconazole (VRZ) was added to the therapeutic regimen with two loading doses of 6mg/kg/d and subsequently 4mg/kg/d b.i.d.; anti-tubercular treatment was discontinued (day 111). Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen showed no evidence of fungal involvement. He was transferred to Infection Diseases Department (day 117). The patient's condition worsened during the subsequent week. A brain MRI revealed progression in the size and number of abscesses (day 138). The largest mass was re-aspirated (day138) which led to clinical recovery of the patient for two weeks. A dark fungus was isolated from the second abscess material (day 143). VRZ antifungal treatment was increased to 200mg/d, i.v. based on susceptibility test results (day 151). A shunt was placed for continuous extra-ventricular drainage and intra-ventricular additional antifungal treatment consisting of 1mg/d L-AMB (day 152) was begun. The shunt malfunctioned on the 20th day and was replaced. Conventional AMB was started (day 172) but discontinued shortly after development of chemical meningitis on day 178. Acute phase reactants were normal. An Omaya reservoir was inserted (day 178) after two more times replacing the catheter. However it had to be discontinued because of recurrent anatomical and technical problems. On day 212, a culture of a CSF sample was negative. As the patient gradually improved he was discharged on day 286 with oral VRZ, methylprednisolone and anti-epileptics. He was followed-up for about two years until his death. Fig. 1 shows brain MRI on days 83, 130 and 496.

Materials and methodsIsolation and phenotypic identificationA brain biopsy, two subsequent aspiration materials from cerebral lesions and a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample were submitted to Deep Mycoses Laboratory on days 102, 109, 133 and 212, respectively. Direct microscopic examination was carried out using Gram, EZN and multiple Giemsa stains of the imprinted tissue specimen, abscess materials and CSF sample. Aseptically divided pieces of the tissue specimens were inoculated, and abscess and CSF samples were plated onto Sabouraud glucose agar (SGA) and chocolate agar (CHA) with sheep blood (5%) plates as primary culture media and incubated at 30°C and 37°C. All plates were sealed with parafilm to maintain adequate humidity for prolonged incubation time. A small portion of biopsy and abscess samples were also inoculated into Sabouraud glucose broth (SGB) and incubated at 30°C. Microscopic morphology of the isolate was examined by staining with lactophenol cotton blue and using unstained wet mounts with saline. Periodic acid schiff (PAS) and hematoxylin-eosin (H-E) stained histopathological preparations from biopsy material of day 101 were also examined. Observations and photomicrographs were made using an Olympus CD2 photomicroscope. The strain was transferred to potato dextrose agar (PDA), Czapek-Dox agar (CZA) and oatmeal agar (OA). Phenotypical identification was made using macroscopic and microscopic characteristics of the isolate.

Molecular identificationThe isolate was identified by sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) domain of rDNA and comparison with reference strains deposited in GenBank and a research database on black fungi housed at CBS.

Antifungal susceptibility testingIn vitro susceptibility of the isolate against AMB, itraconazole (ITZ), fluconazole (FLZ), VRZ and posaconazole (PSZ) were determined by using E-Test strips (bioMérieux, France). Tests were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions and were repeated twice at two-day intervals.

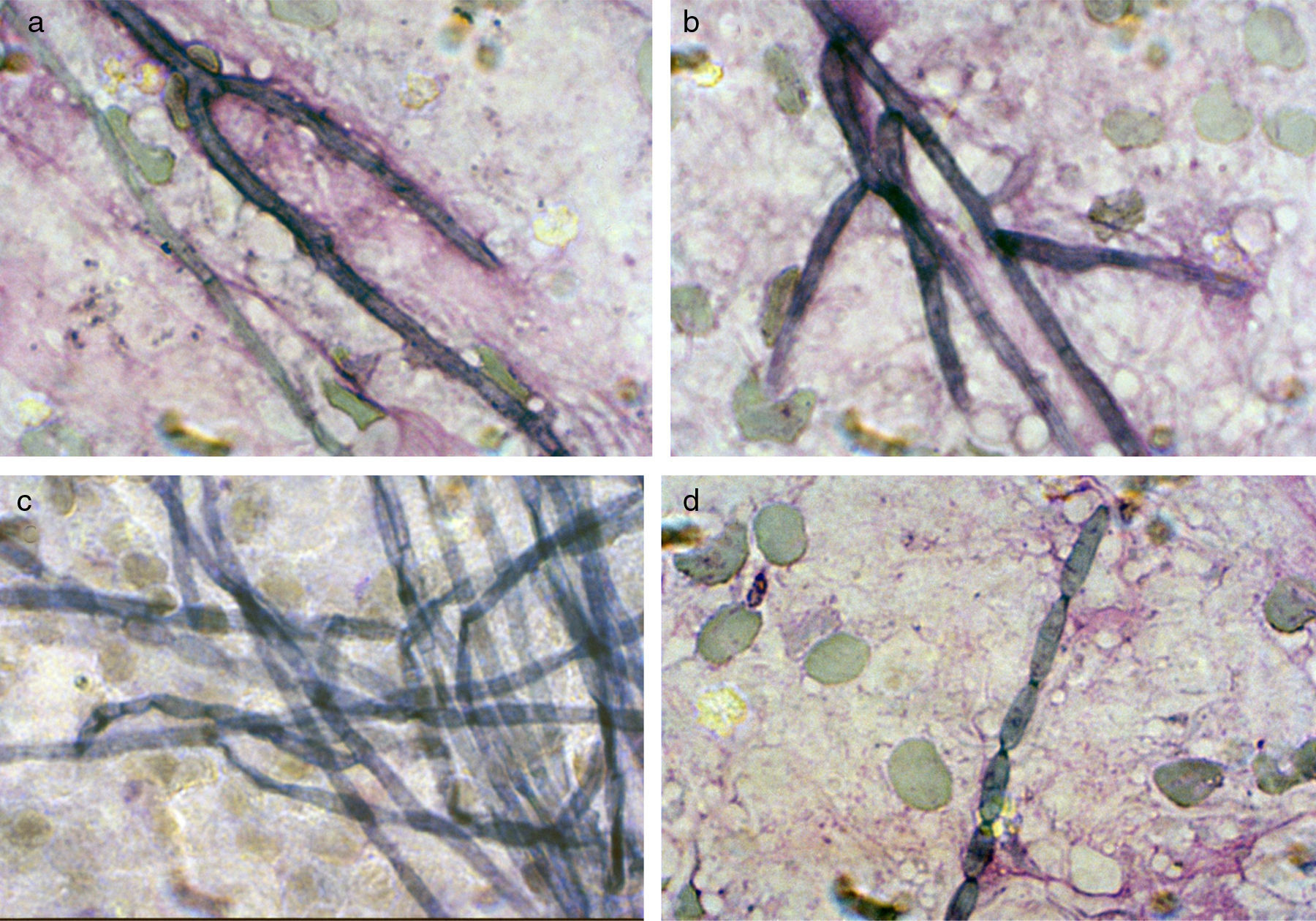

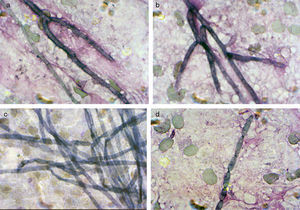

ResultsMycologyDirect microscopical examination of Giemsa stained imprinted tissue slides of the biopsy and two subsequent blackish abscess materials revealed the presence of smooth-walled, ellipsoidal conidia, scarcely septated hyphae and conidial chains arising directly from the hyphae (Fig. 2). Gram and EZN stains did not reveal any organism. In H-E and PAS stained histopathologic preparations the organism appeared in tissue as a few pieces of brown hyphae and polymorphic fungal cells.

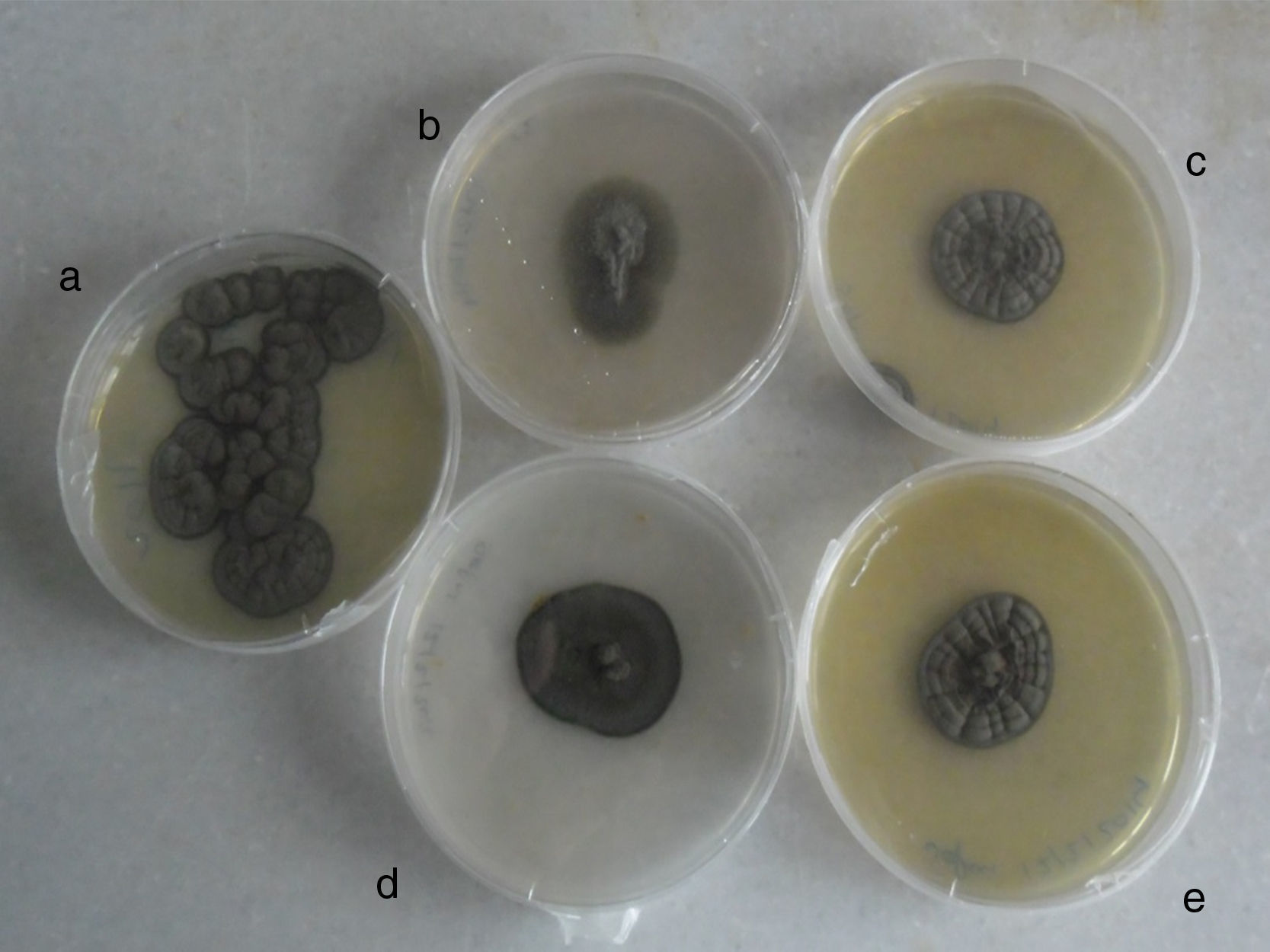

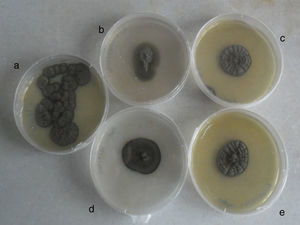

Biopsied tissue and the first aspiration material failed to grow on all media after three weeks of incubation. After four to five days of incubation of the second abscess cultures on SGA at 37°C, abundant blackish colonies grew just over the inoculation line. Combined histopathology and microscopy of the isolate suggested a case of cerebral phaeohyphomycosis. To observe the macro and micromorphology of the isolate, it was subcultured on PDA, CZA and OA, and incubated at 30°C in darkness for two weeks (Fig. 3). Microscopic examination of unstained saline and lactophenol cotton blue stained slides revealed long, occasionally branched chains of olivaceous-brown, ellipsoidal conidia. Fungal structures seen in histopathological sections and in abscess smears were compatible with those of the isolated strain. Morphology, as well as the growth at 40°C and positive urease test result, allowed a tentative identification of the fungus as Cladophialophora sp. The isolate was identified molecularly as C. bantiana by comparing the ITS sequence with those of GenBank. The strain was maintained in the reference collections of Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht and Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, as CBS 140358=FMR 13500.

Antifungal susceptibility resultsThe MICs (μg/ml) were determined as >32 for AMB, >256 for FLZ, 1.5 for ITZ, 1.5 for VRZ, and 0.094 for PSZ. The same MIC values were obtained in duplicate tests.

Laboratory health risk measuresAll patient cultures were immediately killed by autoclaving together with biological indicators and discarded as biohazardous waste. Environmental controls were carried out periodically in both the mycology laboratory and inside the incubators. Petri dishes containing SGA were opened for three hours and then incubated at 30°C and 37°C and no C. bantiana growth was obtained. The Infectious Disease Committee of Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty was officially informed immediately.

DiscussionCladophialophora bantiana is by far the most prevalent agent of fungal brain infection in humans. The species occurs worldwide, with highest frequency on the Indian subcontinent.12 Most infections occur in patients otherwise appearing healthy and often take a fatal course. For this reason C. bantiana has a biosafety level 3 classification, and special precautions have to be taken for laboratory personnel when working with this fungus.

Given this pathology, understanding of the environmental habitat and route of infection are significant for both health laboratories and clinicians to assess the history and laboratory data of occasional cases, and also essential for prophylaxis. However, only very few and paradoxal data are available and address the need of new environmental investigations. Almost all isolates known to date have been derived from human patients, some caused infections in cats and dogs,13 once in a horse (CBS 1382712), almost always with cerebral etiology. Verified environmental strains originated from sawdust (CBS 647.965) or from a SPA filter of a hot tub (CBS 13952414). Our case concerned probable infection by traumatic inoculation from a rock in a mine shaft. The patient had a head injury with laceration of the skin while working in a coalmine, suggesting carbon dust as a possible source of infection. Several isolates had dust as a common factor, but the waterfilter location denies a xerophilic character. Oligotrophism was shared by all environmental habitats, while some had elevated temperatures. The coal mine was hot (around 35°C) and highly humid all year round; the patient had had to change his T-shirts frequently while working. Note that the nearest neighbor of C. bantiana, Cladophialophora psammophila, is known from hydrophobic, hydrocarbon-rich soil.4

If our patient's trauma was indeed linked to inoculation of C. bantiana, the incubation time to develop first symptoms is 54 days. Therapy of cerebral phaeohyphomycoses, and particularly of C. bantiana infections, is not standardized, and mortality rate is high (>70%20). Although the optimal antifungal therapy is not known, AMB, itraconazole and VRZ have been recommended in some case reports.8,17,22 AMB is the most commonly used agent but the drug is ineffective in many cases of cerebral phaeohyphomycosis due to C. bantiana, with or without flucytosine.6,9,10,11,16,21 VRZ showed good in vitro activity3 and has been used in a number of case reports, due to its broad activity and good cerebrospinal fluid penetration; however, failures have been reported.7,19 In the present case, AMB was ineffective in vitro against the isolate, and the fungus showed low MIC values against VRZ and clinically responded to VRZ therapy.

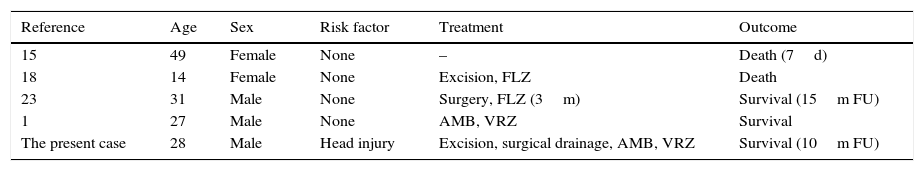

The present case was the fifth reported and the second culturally proven case of cerebral abscess due to C. bantiana in Turkey (Table 1). This case was reported because of its rarity, to alert clinicians to suspect phaeohyphomycosis when evaluating a brain abscess in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients, to caution laboratory workers about the risks of primary neurotropic fungi, and to avoid inhalation of conidia from black mold colonies isolated from CNS associated materials. In addition, the possible traumatic inoculation during a coal mine accident provides further material for speculation on the potential environmental habitat of C. bantiana.

Cerebral phaeohyphomycoses due to C. bantiana reported in Turkey, cases reported from Turkey.

| Reference | Age | Sex | Risk factor | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 49 | Female | None | – | Death (7d) |

| 18 | 14 | Female | None | Excision, FLZ | Death |

| 23 | 31 | Male | None | Surgery, FLZ (3m) | Survival (15m FU) |

| 1 | 27 | Male | None | AMB, VRZ | Survival |

| The present case | 28 | Male | Head injury | Excision, surgical drainage, AMB, VRZ | Survival (10m FU) |

Abbreviations: d, days; m, months; AMB, amphotericin B; FLZ, Fluconazole; FU, follow up; VRZ, voriconazole.

Authors have no conflict of interest.

No funding was received for this work.