As pointed out in the latest consensus recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of Malassezia dermatitis in cats and dogs,1 delivered within the scope of the World Association of Veterinary Dermatology, this disease is now recognised as a common skin disorder in canine practice, and it is encountered only occasionally in feline practice. This disease has evolved from a controversial to a routine diagnosis in small animal practice, with very significant welfare benefits for many animals. In both cats and dogs, erythema, scaly lesions with waxy exudate, and pruritus dominates the clinical presentation, often favouring intertriginous zones.

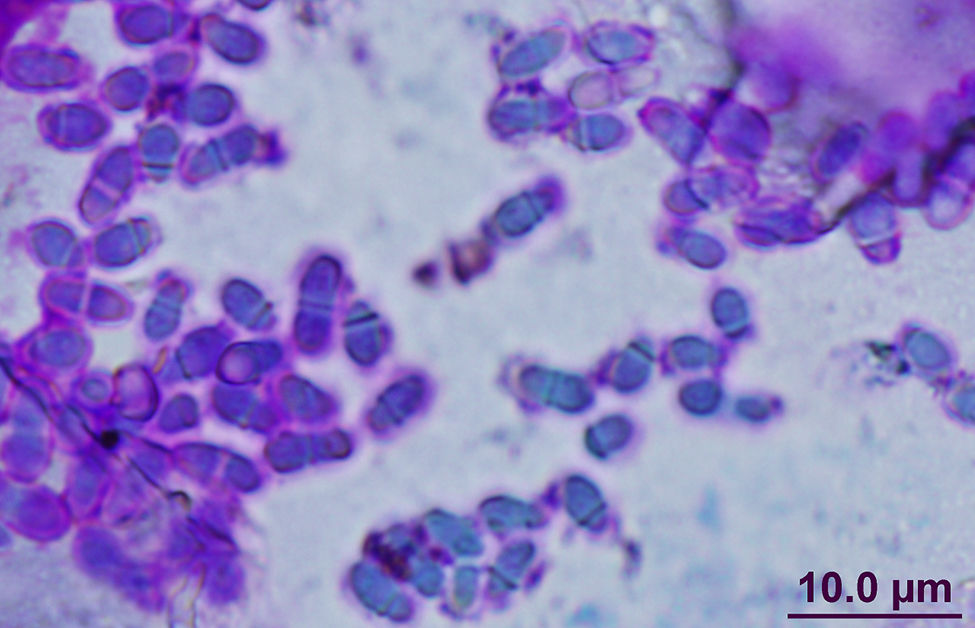

As Malassezia pachydermatis is part of the normal skin microbiota of these animals, the quantification of these yeast cells is a key for the diagnosis of this disorder. Various cytological and culture methods have been proposed for the enumeration of these cell yeasts in the skin. As it is mentioned in these guidelines, veterinary practitioners are used to evaluate M. pachydermatis populations in inflammatory skin lesions by means of cytology. Routine cytological sampling using tape-stripping has gained wide acceptance for recovering cells of the outer layer of the skin and their associated microorganisms. The samples are stained with Diff-Quik stain and observed by light microscopic examination (Fig. 1). However, as outlined in these recommendations, high counts may not necessarily be clinically relevant in each case where they are detected. By contrast, normal or at least lower populations may be enough to exacerbate cutaneous inflammation in patients with immediate or delayed hypersensitivity responses.

On the other hand, otitis externa associated with M. pachydermatis is a common inflammatory disease of the external ear canal of dogs. It is often characterised by the presence of a waxy, moist, and dark exudate, with erythema and pruritus. Diagnosis of the otitis externa caused by M. pachydermatis is based on the observation of compatible lesions, the response to antifungal therapy, and the presence of high counts of yeast cells by direct microscopic examination. In this case, swab sampling is the most common method used for the yeast cell count in the ear canal, either by cytology and/or by culture. Microbiological culture is not usually performed in the clinical setting. However, cytological examination has good specificity but low sensitivity compared to culture and, consequently, there is a need for a specific, sensitive, precise, and rapid method to detect and quantify M. pachydermatis yeasts from dogs with otitis externa.

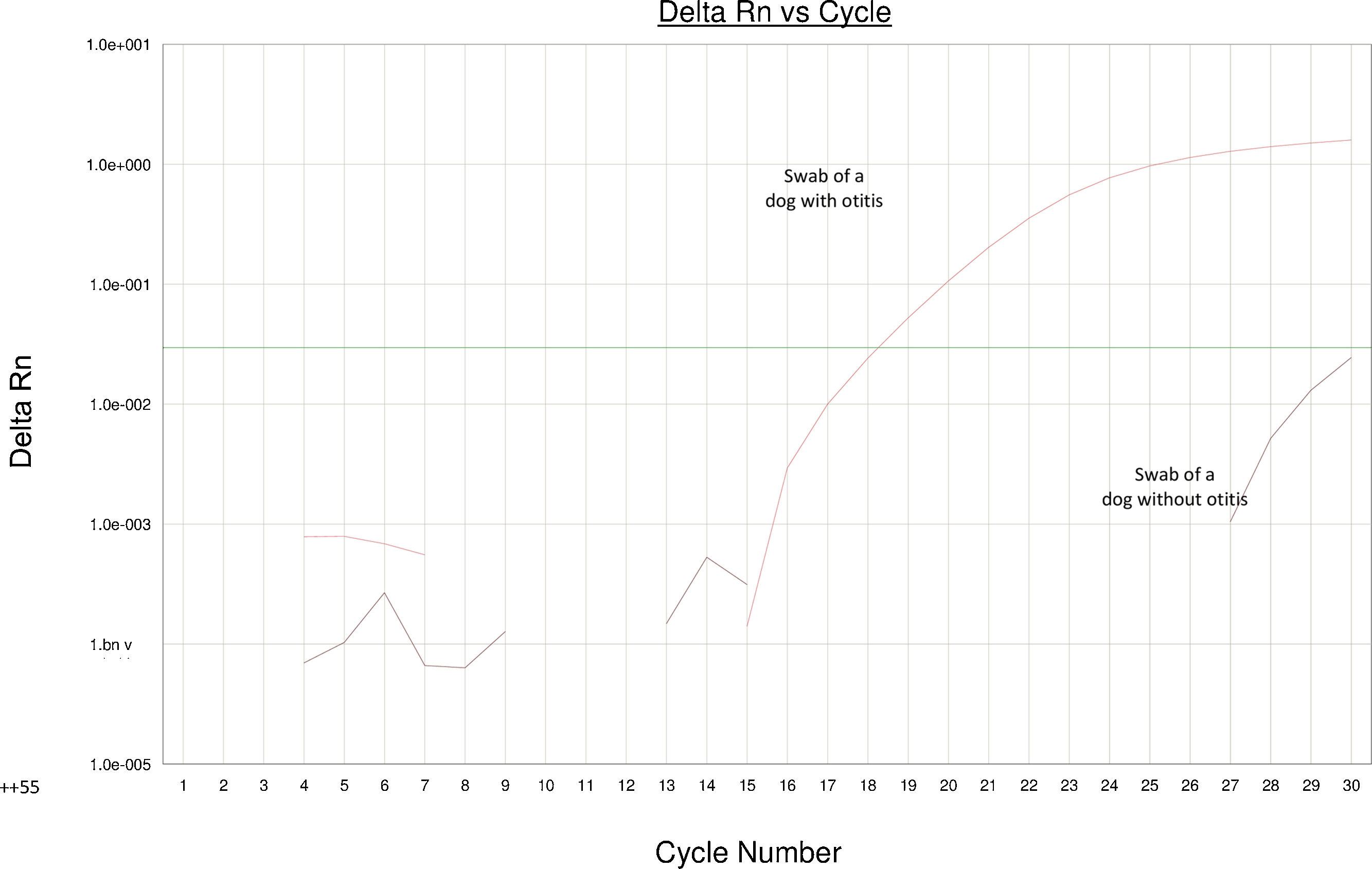

In our laboratory, we recently developed a quantitative PCR (qPCR) to detect and quantify M. pachydermatis yeasts and validate the method using swab sampling from the external ear canals of dogs.2 Our qPCR uses the β-tubulin gene, a single-copy gene, as a target, and provides an accurate quantification of M. pachydermatis yeasts from swab samples from dogs; it is more sensitive than cytology, and could be used to monitor response to the treatment (Fig. 2). Although it is not just a matter of counting yeast cells, this study provides a different and more accurate way of doing it.

Author has no conflict of interest.

Financial support came from Servei Veterinari de Bacteriologia i Micologia of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

These Mycology Forum articles can be consulted in Spanish on the Animal Mycology section on the website of the Spanish Mycology Association (https://aemicol.com/micologia-animal/).