It will soon be 25 years since a 14-month-old male Yorkshire terrier was admitted to the Autonomous University of Barcelona Veterinary Teaching Hospital, with a history of chronic non-productive cough and acute dyspnoea. The dog died five hours after admission. This was our first case of Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP).1 Although much has changed since then, PCP remains a rare disease in dogs and its diagnosis in veterinary clinics is not easy. Moreover, due to its low incidence it is rarely considered in the differential diagnosis in animals presenting with chronic respiratory signs.

Microorganisms belonging to the genus Pneumocystis are single-celled, non-culturable fungi, widely distributed throughout the world.2 Members of this genus have an apparently strict host specificity, probably due to a long history of co-evolution or adaptation to some animal species.

Although these organisms were originally classified as protozoa, nowadays, based on various genomic and phylogenetic analyses, they have been included in the fungal kingdom. However, their cell wall lacks chitin and their cell membrane contains cholesterol instead of ergosterol, characteristics that make them unique in this kingdom. It has recently been found that these organisms form a monophyletic group in the Taphrinomycotina subdivision of the ascomycetes, close to the yeasts of the genus Schizosaccharomyces.

Although these microorganisms infect a wide range of mammalian species, only five species have been formally proposed so far: Pneumocystis jirovecii in humans, Pneumocystis murina in mice, Pneumocystis oryctolagi in rabbits, and Pneumocystis carinii and Pneumocystis wakefieldiae in rats. Pneumocystis organisms found in other mammals are often referred to by using the infraspecific taxon “forma specialis” (e.g. Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. canis in dogs). The life cycle of these microorganisms remains poorly understood because they cannot be cultured in vitro.

As extracellular parasites, these organisms have been found almost exclusively in the alveolar spaces of mammalian lungs. Due to their new taxonomic position, it has been hypothesised that the life cycle of Pneumocystis includes an asexual and a sexual phase, with two primary morphological forms: the trophic form or trophozoite, and the cystic form or ascus, which is the infectious form responsible for transmission.

In a recent review which includes most published cases of PCP in dogs,3 the authors point out that PCP is most commonly diagnosed in young animals and more frequently in certain breeds, such as the Cavalier King Charles spaniel and the miniature dachshund, which are predisposed to a certain degree of immunodeficiency. In this study, tachypnoea, dyspnoea and cough were the most frequent respiratory signs.

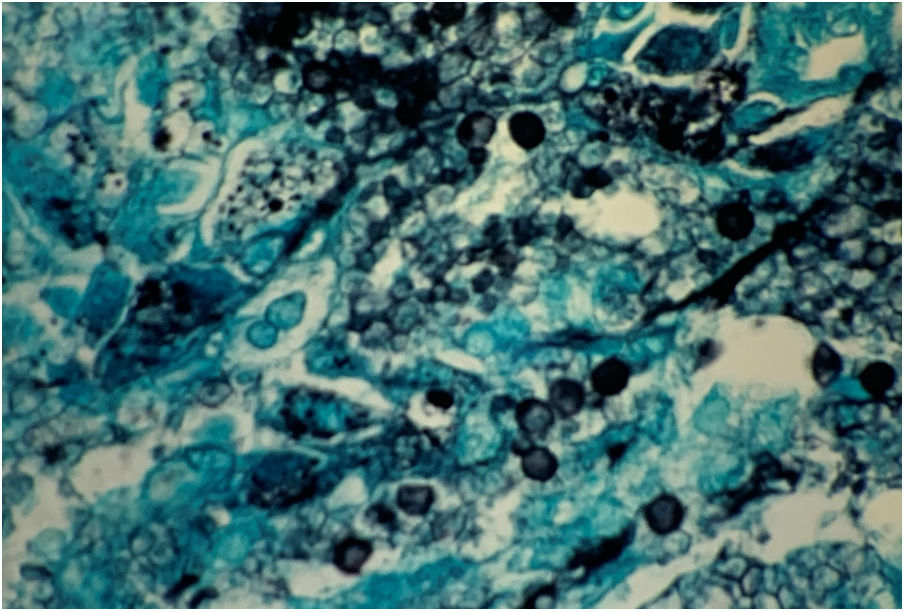

In human medicine, bronchoalveolar lavage is considered the gold standard diagnostic procedure for pneumocystosis. Unfortunately, this technique does not seem to be useful to find out in samples from dogs the different forms of Pneumocystis. In contrast, lung aspirates and lung smears are positive in almost all cases. For the latter type of samples and for paraffin-embedded tissue samples, the Grocott stain is the most sensitive and easy-to-use technique, compared to other stains, due to a higher colour contrast of the black walls of the cysts within the mainly green background (Fig. 1).

Cysts (dark structures) and trophic forms (light-green structures) of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. canis filling alveolar spaces of a dog with pneumocystosis.1 Grocott-methenamine-silver stain.

Although other techniques that reveal the presence of these pathogens (e.g. immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridisation) have been described, it seems that PCR has certain advantages and could avoid undergoing invasive surgical interventions. Due to its high sensitivity, this technique could be useful in bronchoalveolar lavage samples. As mentioned above, these samples usually have a low Pneumocystis load, which makes it difficult to find this organism by means of cytology.

In dogs with PCP, starting an immediate treatment may lead to their recovery. The use of trimethoprim-sulphonamide combined with low doses of anti-inflammatory corticosteroids substantially increases the chances of survival of the affected dogs. Alveolar macrophages produce several mediators that enhance the inflammatory response to Pneumocystis, and their massive release can increase lung injury and respiratory impairment. Misdiagnosis or late diagnosis can lead to disease progression, with severe respiratory dysfunction or, in most cases, to the death of the animal.

Conflict of interestAuthor has no conflict of interest.

Financial support came from Servei Veterinari de Bacteriologia i Micologia of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

These Mycology Forum articles can be consulted in Spanish on the Animal Mycology section on the website of the Spanish Mycology Association (https://aemicol.com/micologia-animal/).